Abstract

AIM: To determine the risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) rupture, and report the management and long-term survival results of patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC.

METHODS: Among 4209 patients with HCC who were diagnosed at Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital from April 2002 to November 2006, 200 (4.8%) patients with ruptured HCC (case group) were studied retrospectively in term of their clinical characteristics and prognostic factors. The one-stage therapeutic approach to manage ruptured HCC consisted of initial management by conservative treatment, transarterial embolization (TACE) or hepatic resection. Results of various treatments in the case group were evaluated and compared with the control group (202 patients) without ruptured HCC during the same study period. Continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD or median (range) where appropriate and compared using the unpaired t test. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square test with Yates correction or the Fisher exact test where appropriate. The overall survival rate in each group was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method and a log-rank test.

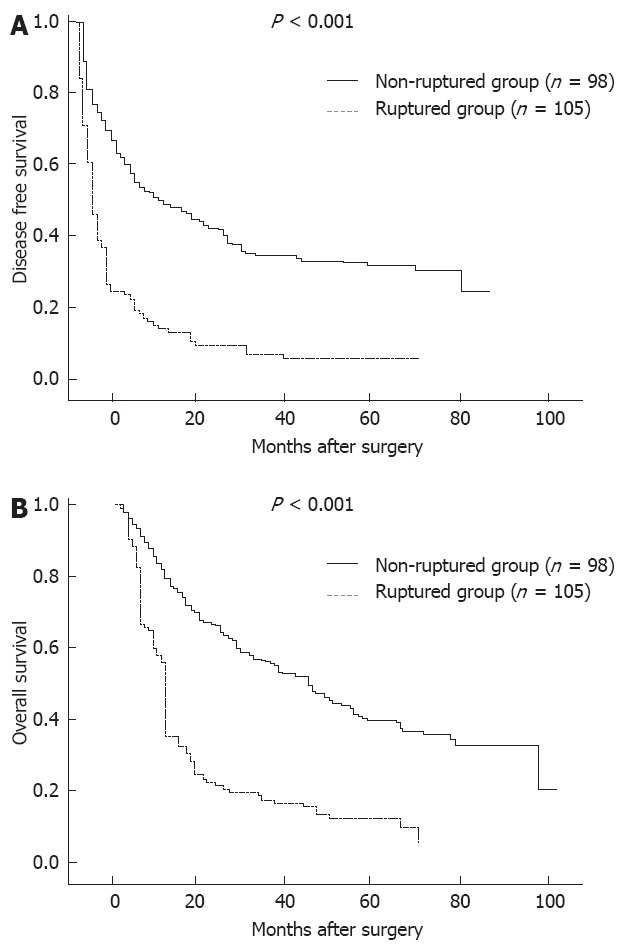

RESULTS: Compared with the control group, more patients in the case group had underlying diseases of hypertension (7.5% vs 3.0%, P =0.041) and liver cirrhosis (87.5% vs 56.4%, P < 0.001), tumor size >5 cm (83.0% vs 57.4%, P < 0.001), tumor protrusion from the liver surface (66.0% vs 44.6%, P < 0.001), vascular thrombus (30.5% vs 8.9%, P < 0.001) and extrahepatic invasion (36.5% vs 12.4%, P < 0.001). On multivariate logistic regression analysis, underlying diseases of hypertension (P = 0.002) and liver cirrhosis (P < 0.001), tumor size > 5 cm (P < 0.001), vascular thrombus (P = 0.002) and extrahepatic invasion (P < 0.001) were predictive for spontaneous rupture of HCC. Among the 200 patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC, 105 patients underwent hepatic resection, 33 received TACE, and 62 were managed with conservative treatment. The median survival time (MST) of all patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC was 6 mo (range, 1-72 mo), and the overall survival at 1, 3 and 5 years were 32.5%, 10% and 4%, respectively. The MST was 12 mo (range, 1-72 mo) in the surgical group, 4 mo (range, 1-30 mo) in the TACE group and 1 mo (range, 1-19 mo) in the conservative group. Ninety-eight patients in the control group underwent hepatic resection, and the MST and median disease-free survival time were 46 mo (range, 6-93 mo) and 23 mo (range, 3-39 mo) respectively, which were much longer than that of patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC undergoing hepatic resection (P < 0.001). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates and the 1-, 3- and 5-year disease-free survival rates in patients with ruptured HCC undergoing hepatectomy were 57.1%, 19.0% and 7.6%, 27.6%, 14.3% and 3.8%, respectively, compared with those of 77.1%, 59.8% and 41.2%, 57.1%, 40.6% and 32.9% in 98 patients without ruptured HCC undergoing hepatectomy (P < 0.001).

CONCLUSION: Prolonged survival can be achieved in selected patients undergoing one-stage hepatectomy, although the survival results were inferior to those of the patients without ruptured HCC.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, Spontaneous rupture, Predictors, Hepatectomy, Overall survival, Disease-free survival

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common neoplasms, and its incidence is increasing worldwide because of the increasing prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infection[1,2]. One of the life-threatening complications of HCC is the spontaneous rupture of the tumor, with intra-peritoneal hemorrhage. Spontaneous rupture of HCC occurs in 3%-26% of all patients with HCC, and the mortality rates are high in a range of 32%-66.7%[3-7].

There are few reports of predictors for spontaneous rupture of HCC[8-10]. In addition, clinicians often feel helpless when facing these complicated situations, and little information is available in the literature to guide clinicians as to the most appropriate management of this complication. The prognosis of ruptured HCC was poor, a median survival of 1.2-4 mo if left untreated[11], but some studies have reported better survival with staged hepatectomy[3]. There is still a debate concerning the best approach in cases of HCC rupture[12]. The following treatments have been employed for the ruptured HCC: hepatic resection, conservative treatment and transcatheter arterial embolization (TACE)[8,11-14]. It is also unclear whether the clinical outcome of definitive treatment including hepatic resection was affected by the complication of tumor rupture.

We, therefore, conducted this retrospective study to determine the risk factors for HCC rupture, and to report the management of patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC and long-term survival results during a 5-year period at a single center in China.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

From April 2002 to November 2006, 4209 patients with HCC visited Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital. Among them, 200 patients (4.8%) had hemoperitoneum due to spontaneous rupture of the tumor. The clinical records of these 200 patients (case group) were retrospectively reviewed and compared with 202 patients without ruptured HCC (control group) who were randomly chosen by matching age, sex and time of admission from the patients who visited our hospital in the same period.

All patients had a chest X-ray, ultrasonography (USG) of abdomen, and contrast computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of abdomen. Laboratory blood tests were performed, including antigen to hepatitis B surface, antibodies to hepatitis C, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, serum albumin, total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, prothrombin time and so on. Progression profile of HCC (number of tumors, maximum tumor size, macroscopic tumor thrombus and extrahepatic invasion), treatments employed, and survival time were recorded. The liver function status was evaluated using the Child-Pugh classification system. HCC was staged according to the tumor node metastasis (TNM) staging system proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC)[15].

HCC was diagnosed by at least two radiologic imaging examinations showing characteristic features of HCC, or one radiologic imaging examination showing characteristic features of HCC associated with AFP ≥400 ng/mL. Ruptured HCC was diagnosed by the identification of a space-occupying lesion(s) in the liver using USG, CT or MRI. The following CT findings are useful for diagnosing a ruptured HCC: hemoperitoneum, HCC with surrounding perihepatic hematoma, active extravasation of contrast materials, tumor protrusion from the hepatic surface, focal discontinuity of the hepatic surface and an enucleation sign[5].

Therapeutic options were determined for each patient according to the tumor feature and liver function. Selected patients with resectable tumor(s) and well preserved liver function were considered for surgery, and these patients with Child-Pugh class A liver function underwent major hepatic resection, while those patients with Child-Pugh class B liver function received minor hepatic resection. Patients with unresectable tumor(s) and well preserved liver function were considered for TACE, while those with poor liver function (Child-Pugh class C) were suggested to receive conservative treatment.

Statistical analysis

Information of patient details, intraoperative parameters, postoperative course, and disease progress was collected and analyzed retrospectively. Continuous data were presented as mean ± SD or median (range) where appropriate and compared using the unpaired t test. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test with Yates correction or the Fisher exact test where appropriate. Factors associated with a P value < 0.05 in the univariate analysis were sequentially entered into the multivariate logistic regression analysis to indicate the relatively independent risk factors.

Group comparisons were performed using the Chi-square test for independence or the Fisher exact test for comparisons of the two groups. The overall survival rate in each group was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method and a log-rank test. The survival period defined as the length of time from the onset of the spontaneous rupture of the HCC to the death of the patient or the closing date of the study. The closing date for the study was November 31, 2011.

RESULTS

Clinical data between the case group and the control group are presented in Table 1. The initial symptoms of spontaneous rupture of HCC were the sudden onset of abdominal pain (134 patients, 67%), shock at admission (102 patients, 51%), and abdominal distension (66 patients, 33%).

Table 1.

Univariate analysis of risk factors related to spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma

| Variables | Case group (n = 200) | Control group (n = 202) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 47.9 ± 12.4 | 50.5 ± 11.4 | 0.209 |

| Sex | 0.322 | ||

| Male | 184 | 180 | |

| Female | 16 | 22 | |

| Diabetes | 0.388 | ||

| Presence | 8 | 5 | |

| Absence | 192 | 197 | |

| Hypertension | 0.041 | ||

| Presence | 15 | 6 | |

| Absence | 185 | 196 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 175 | 114 | |

| No | 25 | 88 | |

| Liver function status | 0.096 | ||

| Child-Pugh class A | 133 | 157 | |

| Child-Pugh class B | 49 | 32 | |

| Child-Pugh class C | 18 | 13 | |

| PT (s) | 13.8 ± 2.3 | 13.3 ± 1.5 | 0.328 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 161.4 ± 94.8 | 159.1 ± 64.6 | 0.187 |

| TB (μmol/L) | 34.4 ± 40.6 | 30.0 ± 6.7 | 0.097 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.2 ± 5.8 | 36.8 ± 4.2 | 0.101 |

| ALT(IU/L) | 86.0 ± 91.6 | 59.4 ± 48.1 | 0.261 |

| AST(IU/L) | 136.2 ± 176.4 | 59.8 ± 47.5 | 0.643 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 72.6 ± 20.2 | 74.3 ± 18.7 | 0.209 |

| AFP (μg/L) | 586.6 (1.3-95600.5) | 499.2 (1.8-10521.6) | 0.125 |

| Positive HBsAg status | 181 | 166 | 0.514 |

| Maximum tumor size (cm) | < 0.001 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 34 | 86 | |

| > 5 | 166 | 116 | |

| Tumor location | 0.927 | ||

| Right lobe | 142 | 146 | |

| Left lobe | 38 | 38 | |

| Both lobes | 20 | 18 | |

| Protrusion from the liver surface | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 132 | 90 | |

| No | 68 | 112 | |

| Vascular thrombus | < 0.001 | ||

| Presence | 61 | 18 | |

| Absence | 139 | 184 | |

| Ascites | 0.301 | ||

| Presence | 24 | 16 | |

| Absence | 176 | 186 | |

| Extrahepatic invasion | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 73 | 25 | |

| No | 127 | 177 | |

PT: Prothrombin time; PLT: Platelet count; TB: Total bilirubin; AFP: α-fetoprotein; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase.

Risk factors related to spontaneous rupture of HCC

Compared with the control group, more patients in the case group had underlying diseases of hypertension (7.5% vs 3.0%, P = 0.041) and liver cirrhosis (87.5% vs 56.4%, P < 0.001), tumor size > 5 cm (83.0% vs 57.4%, P < 0.001), tumor protrusion from the liver surface (66.0% vs 44.6%, P < 0.001), vascular thrombus (30.5% vs 8.9%, P < 0.001) and extrahepatic invasion (36.5% vs 12.4%, P < 0.001) (Table 1). On multivariate logistic regression analysis, underlying diseases of hypertension and liver cirrhosis, tumor size > 5 cm, tumor protrusion from the liver surface, vascular thrombus and extrahepatic invasion remained predictive for spontaneous rupture of HCC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis for factors related with spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma

| Variables | HR | 95%CI for HR | P value |

| Hypertension (presence vs absence) | 7.75 | 2.10-28.57 | 0.002 |

| Liver cirrhosis (presence vs absence) | 7.16 | 3.96-12.97 | < 0.001 |

| Tumor size (≤ 5 cm vs > 5 cm) | 3.97 | 2.28-6.93 | < 0.001 |

| Protrusion from the liver surface (yes vs no) | 6.51 | 2.31-10.84 | 0.008 |

| Vascular thrombus (presence vs absence) | 2.90 | 1.48-5.70 | 0.002 |

| Extrahepatic invasion (yes vs no) | 3.78 | 2.04-7.00 | < 0.001 |

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma; HR: Hazard ratio; CI: Confidence interval.

Management of patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC

Among the 200 patients with spontaneous ruptured HCC, 126 (63%) had stage I or II HCCs according to the TNM staging system proposed by the AJCC[15]. After recovery from the initial insult with blood replacement, correction of coagulopathy and cardiovascular monitoring and complete clinical evaluation, 105 patients were considered suitable for curative hepatic resection which was performed on a median of 15 d (range, 7-35 d) after rupture, 33 received TACE, and 62 were given conservative treatment. Of the 105 patients considered for hepatic resection, 72 (58.1%) underwent major hepatic resection while the remaining ones received minor hepatic resection. Operative details of these 105 patients undergoing hepatectomy are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Operative detail of 105 patients undergoing hepatectomy

| Detail | n |

| Type of hepatectomy | 105 |

| Minor hepatectomy | 43 |

| Major hepatectomy | 62 |

| Operating time (min) | 166.8 ± 70.2 |

| Duration of blood inflow occlusion (min) | 16.9 ± 9.0 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 811.4 (50-5000) |

| Surgical margins | |

| R0 resection | 92 |

| R1 resection | 12 |

| R2 resection | 1 |

| Hospital mortality | 1 |

| Major complications | |

| Post-operative bleeding | 0 |

| Liver failure | 1 |

| Bile leak | 1 |

| Pleural effusion | 51 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 17.3 ± 6.7 |

Acute hemorrhage was successfully controlled in all patients (100%) undergoing hepatic resection during the first hospital admission, compared with 31.0% patients receiving TACE and 16.5% patients receiving conservative treatment. One patient (0.9%) died of liver failure on day 20 after hepatic resection, 10 (30.3%) patients died of liver failure after TACE and 36 (58.1%) patients died of bleeding after conservative treatment within 30 days of hospitalization, respectively.

Survival analysis of patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC

At the closing date of the study, 187 patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC died, including 92 (87.6%) in the surgical group, 33 (100%) in the TACE group and 62 (100%) in the conservative group. The median survival time (MST) of all patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC was 6 mo (range, 1-72 mo), and the overall survival rates at 1, 3 and 5 years were 32.5%, 10% and 4%, respectively. The MST was 12 mo (range, 1-72 mo) in the surgical group, 4 mo (range, 1-30 mo) in the TACE group and 1 mo (range, 1-19 mo) in the conservative group. The 1-, 3-, and 5-year overall survival rates in the surgical group were 57.1%, 19.0% and 7.6%, respectively, while they were 12.1%, 0% and 0% in the TACE group and 1.6%, 0% and 0% in the conservative group. In addition, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year disease-free survival rates of surgical group were 27.6%, 14.3% and 3.81%, respectively, while they were 9.1%, 0% and 0% in the TACE group and none in the conservative group.

In the 98 patients in the control group who underwent hepatic resection, the MST and median disease-free survival time were 46 mo (range, 6-93 mo) and 23 mo (range, 3-39 mo), respectively, which were much longer than in the patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC undergoing hepatic resection (P < 0.001). Accordingly, the 1-, 3- and 5-year overall survival rates of these 98 patients were 77.1%, 59.8% and 41.2%, and the 1-, 3- and 5-year disease-free survival rates were 57.1%, 40.6% and 32.9%, both of which were significantly longer than that of patients with spontaneous rupture of HCC undergoing hepatic resection (P < 0.001) (Figure 1) .

Figure 1.

Overall survival and disease-free survival in patients with and without ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing hepatic resection.

DISCUSSION

As a life-threatening complication of HCC, spontaneous rupture of HCC is one of the most common emergencies in liver surgery. Seeking for the risk factors failed to conclude a widely accepted result[5,16].

A widely accepted hypothesis for the mechanism of rupture of HCC suggests that rupture is usually preceded by rapid expansion of the tumor secondary to bleeding from within its substance, and a high intratumoral pressure due to occlusion of the hepatic venous outflow by tumor invasion results in rupture[9]. In our study, we found that tumor protrusion from the liver surface, vascular thrombus and extrahepatic invasion were predictive for spontaneous rupture of HCC, which were consistent with previous studies[5,9,16]. The protruded tumor without surrounding normal parenchyma may easily rupture due to compression or friction to the adjacent diaphragmatic muscle, abdominal wall and gastrointestinal tracts. Therefore, the presence of extrahepatic invasion more likely leads to rupture. Moreover, the maximum tumor size > 5 cm was one of the risk factors predicting rupture of HCC. However, in our study, rupture of tumors as small as 2 cm was found, which was consistent with a report by Tanaka et al[17]. It is difficult to explain how a small HCC located in the periphery of the liver would rupture by above mechanism. More recent studies suggested that underlying vascular dysfunction may play a role[8]. The vessels in the ruptured HCC tend to be more friable due to increased collagenase expression and increased collagen IV degradation[10]. This proposed mechanism may help to explain why some of the small tumors also rupture.

Interestingly, in our study, the presence of hypertension and liver cirrhosis remained predictive for spontaneous rupture of HCC. The reasons may be as follows. HCC is a vascular tumor and bleeding secondary to rupture can cause tearing of vessels with uncontrollable blood loss, hypertension can directly result in an increase of pressure within the tumor. In addition, patients with cirrhosis have underlying coagulopathy. Both of the two factors may promote the process of rupture described above.

Previous studies have shown a very poor prognosis, with a 30-d mortality rate in the range of 30%-70%[13,19-21], and recent reports have indicated a significant decrease in the mortality rate. In our study, we observed an overall 30-d mortality rate of 23.5%, while the mortality rate was only 0.95% (one patient) among the patients in whom hepatectomy was successfully conducted.

In another series, the 1-year and 3-year survival rates for patients who underwent emergency resection were only 60% and 42%, respectively[22]. Miyamoto et al[23] reported that half of the hospital mortality of emergency hepatectomy for ruptured HCC was due to liver failure. One group reported that only 12.5% of the patients with ruptured HCC could be managed with hepatic resection, while another group reported a percentage of 59.3%[4,24,25]. In our study, which yielded similar results, 52.5% (105/200) of patients with ruptured HCC could be managed with hepatic resection. In two case series of delayed resection for ruptured HCCs from Japan, no in-hospital mortality was observed, and 1- and 3-year survival rates of 71%-77% and 48%-54%, respectively, were achieved[26,27]. In our series, the 1-year, 3-year and 5-year survival rates were 57.1%, 19.0% and 7.6%, respectively, for the patients with one-stage resection, and the MST in the surgical group was 12 mo.

For patients with unresectable HCC, TACE was the best option for the treatment of patients with ruptured tumor, and the MST in the TACE group was significantly longer than that in the conservative group. Most of the patients in the conservative group died within 1 mo as a result of re-rupture, re-bleeding or hepatic failure.

Historically, the prognosis for ruptured HCC is thought to be worse than for non-ruptured HCC, due to multiple factors. The patients with ruptured HCC harbor advanced disease at presentation, the incidence of coexisting cirrhosis is high, and peritoneal seeding may occur at the time of rupture. However, recent studies have challenged this concept, stating that the long-term survival for ruptured HCC may be equivalent to non-ruptured HCC[20], especially when the comparison was adjusted for tumor stage[28]. However, in our study, patients with ruptured HCC had a much worse long-term prognosis than those without.

In conclusion, spontaneous ruptured HCC is a life threatening condition and a commonly encountered surgical emergency. For HCC patients who had underlying diseases of hypertension and liver cirrhosis, extrahepatic invasion and tumor size > 5 cm, high propensity to rupture should be considered. As long as preoperative clinical evaluation meets surgery requirements, elective one-stage hepatectomy in patients with ruptured HCC should be suggested. Prolonged survival can be achieved in selected patients undergoing one-stage hepatectomy, although the survival results were inferior to those of the patients who did not have the complication of rupture.

COMMENTS

Background

Spontaneous ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a life threatening condition and a commonly encountered surgical emergency. There are few reports of predictors for spontaneous rupture of HCC. It was also not clear whether the clinical outcome of definitive treatment including hepatic resection is affected by the complication of tumor rupture.

Research frontiers

Seeking for the risk factors failed to conclude a widely accepted result. Several recent studies reported better survival with staged hepatectomy, and challenged traditional concept, stating that the long-term survival for ruptured HCC may be equivalent to non-ruptured HCC. There is still a debate concerning the best approach in cases of HCC rupture.

Innovations and breakthroughs

In this study, the presence of hypertension and liver cirrhosis remained predictive for spontaneous rupture of HCC. Patients with ruptured HCC had a much worse long-term prognosis than those without.

Applications

The study results suggest that for HCC patients who had underlying diseases of hypertension and liver cirrhosis, extrahepatic invasion and tumor size>5 cm, high propensity to rupture should be considered. Prolonged survival can be achieved in selected patients undergoing one-stage hepatectomy, although the survival results were inferior to those of the patients who did not have the complication of rupture.

Terminology

HCC is the most common primary malignant tumor of the liver which originates from liver parenchymal cells. Spontaneous rupture of HCC refers to the HCC ruptured without any sign.

Peer review

The authors analyzed the clinical data of patients with spontaneous ruptured HCC and non-ruptured HCC for detecting the risk factors for HCC rupture, and reporting the management and long-term survival results of patients with spontaneous ruptured of HCC. They determined the risk factors and evaluated the prognosis for spontaneous rupture of HCC. This conclusion well guided clinicians as to the most appropriate management of this complication. The study was carefully designed and the evaluation of the results was also appropriate. The manuscript was well organized and well written.

Footnotes

Supported by National Science and Technology Major Project Foundation, No. 2008ZX10002-025

Peer reviewer: Manabu Morimoto, MD, Gastroenterological Center, Yokohama City University Medical Center, 4-57 Urafune-cho, Minami-ku, Yokohama 232-0024, Japan

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor Ma JY E- Editor Lu YJ

References

- 1.McGlynn KA, London WT. The global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: present and future. Clin Liver Dis. 2011;15:223–43, vii-x. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi M, Ikeda K, Hosaka T, Sezaki H, Someya T, Akuta N, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y, et al. Natural history of compensated cirrhosis in the Child-Pugh class A compared between 490 patients with hepatitis C and 167 with B virus infections. J Med Virol. 2006;78:459–465. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyoshi A, Kitahara K, Kohya N, Noshiro H, Miyazahi K. Outcomes of patients with spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu CL, Fan ST, Lo CM, Tso WK, Poon RT, Lam CM, Wong J. Management of spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: single-center experience. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3725–3732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.17.3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HC, Yang DM, Jin W, Park SJ. The various manifestations of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma: CT imaging findings. Abdom Imaging. 2008;33:633–642. doi: 10.1007/s00261-007-9353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim YI, Ki HS, Kim MH, Cho DK, Cho SB, Joo YE, Kim HS, Choi SK, Rew JS. [Analysis of the clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma] Korean J Hepatol. 2009;15:148–158. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2009.15.2.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan FL, Tan YM, Chung AY, Cheow PC, Chow PK, Ooi LL. Factors affecting early mortality in spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:448–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhu LX, Geng XP, Fan ST. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma and vascular injury. Arch Surg. 2001;136:682–687. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.6.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu LX, Wang GS, Fan ST. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1996;83:602–607. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800830507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu LX, Liu Y, Fan ST. Ultrastructural study of the vascular endothelium of patients with spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian J Surg. 2002;25:157–162. doi: 10.1016/S1015-9584(09)60166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Mashat FM, Sibiany AM, Kashgari RH, Maimani AA, Al-Radi AO, Balawy IA, Ahmad JE. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:866–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossetto A, Adani GL, Risaliti A, Baccarani U, Bresadola V, Lorenzin D, Terrosu G. Combined approach for spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2010;2:49–51. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v2.i1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida H, Mamada Y, Taniai N, Mizuguchi Y, Kakinuma D, Ishikawa Y, Kanda T, Matsumoto S, Bando K, Akimaru K, et al. Long-term results of elective hepatectomy for the treatment of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:178–182. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1239-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarantino L, Sordelli I, Calise F, Ripa C, Perrotta M, Sperlongano P. Prognosis of patients with spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis. Updates Surg. 2011;63:25–30. doi: 10.1007/s13304-010-0041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. The general rules for the clinical and pathological study of primary liver cancer, 2th ed. Tokyo: Kanehara; 2003. pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen CY, Lin XZ, Shin JS, Lin CY, Leow TC, Chen CY, Chang TT. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. A review of 141 Taiwanese cases and comparison with nonrupture cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:238–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka A, Takeda R, Mukaihara S, Hayakawa K, Shibata T, Itoh K, Nishida N, Nakao K, Fukuda Y, Chiba T, et al. Treatment of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2001;6:291–295. doi: 10.1007/s10147-001-8030-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buczkowski AK, Kim PT, Ho SG, Schaeffer DF, Lee SI, Owen DA, Weiss AH, Chung SW, Scudamore CH. Multidisciplinary management of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hai L, Yong-Hong P, Yong F, Ren-Feng L. One-stage liver resection for spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2005;29:1316–1318. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7626-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yeh CN, Lee WC, Jeng LB, Chen MF, Yu MC. Spontaneous tumour rupture and prognosis in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1125–1129. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chiappa A, Zbar A, Audisio RA, Paties C, Bertani E, Staudacher C. Emergency liver resection for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma complicating cirrhosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1145–1150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen MF, Hwang TL, Jeng LB, Jan YY, Wang CS. Clinical experience with hepatic resection for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:166–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyamoto M, Sudo T, Kuyama T. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a review of 172 Japanese cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:67–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cherqui D, Panis Y, Rotman N, Fagniez PL. Emergency liver resection for spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma complicating cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 1993;80:747–749. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewar GA, Griffin SM, Ku KW, Lau WY, Li AK. Management of bleeding liver tumours in Hong Kong. Br J Surg. 1991;78:463–466. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimada R, Imamura H, Makuuchi M, Soeda J, Kobayashi A, Noike T, Miyagawa S, Kawasaki S. Staged hepatectomy after emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 1998;124:526–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shuto T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Tanaka H, Hamba H, Kubota D, Kinoshita H. Delayed hepatic resection for ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery. 1998;124:33–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mizuno S, Yamagiwa K, Ogawa T, Tabata M, Yokoi H, Isaji S, Uemoto S. Are the results of surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma poor if the tumor has spontaneously ruptured? Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:567–570. doi: 10.1080/00365520410005135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]