Abstract

Background:

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) can help smokers to quit smoking. Nicotine chewing gum has attracted the attention from pharmaceutical industries to offer it to consumers as an easily accessible NRT product. However, the bitter taste of such gums may compromise their acceptability by patients. This study was, therefore, designed to develop 2 and 4 mg nicotine chewing gums of pleasant taste, which satisfy the consumers the most.

Materials and Methods:

Nicotine, sugar, liquid glucose, glycerin, different sweetening and taste-masking agents, and a flavoring agent were added to the gum bases at appropriate temperature. The medicated gums were cut into pieces of suitable size and coated by acacia aqueous solution (2% w/v), sugar dusting, followed by acacia–sugar–calcium carbonate until a smooth surface was produced. The gums’ weight variation and content uniformity were determined. The release of nicotine was studied in pH 6.8 phosphate buffer using a mastication device which simulated the mastication of chewing gum in human. The Latin Square design was used for the evaluation of organoleptic characteristics of the formulations at different stages of development.

Results:

Most formulations released 79–83% of their nicotine content within 20 min. Nicotine-containing sugar-coated gums in which aspartame as sweetener and cherry and eucalyptus as flavoring agents were incorporated (i.e. formulations F19-SC and F20-SC, respectively) had optimal chewing hardness, adhering to teeth, and plumpness characteristics, as well as the most pleasant taste and highest acceptability to smokers.

Conclusion:

Taste enhancement of nicotine gums was achieved where formulations comprised aspartame as the sweetener and cherry and eucalyptus as the flavoring agents. Nicotine gums of pleasant taste may, therefore, be used as NRT to assist smokers quit smoking.

Keywords: Nicotine chewing gum, nicotine replacement therapy, nicotine addiction, smoking cessation

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use through cigarette smoking is the leading avoidable cause of death in the world; it kills almost 4 million people each year. According to the World Health Organization, 10 million smokers will die per year by 2030.[1] There are over 4000 chemicals in cigarette smoke,[2] including 43 carcinogenic compounds and 400 other toxins such as nicotine, tar, carbon monoxide, as well as formaldehyde, ammonia, hydrogen cyanide, arsenic, and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT).[3] Nicotine is the main active component in cigarette that reinforces individual smoking behavior. However, there are other ingredients of tobacco and not nicotine that lead to the mortality and morbidity.[4] People become dependent on the nicotine in cigarette because it raises the levels of special chemicals, such as dopamine and norepinephrine, in their brains.[5] Smoking cessation at any age decreases the morbidity. When people stop smoking, the levels of those chemicals fall, and reactions of body appear as nicotine withdrawal syndrome such as craving for tobacco, irritability, nervousness, difficulty concentrating, impatience, insomnia, and increased appetite.[6]

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) can help smokers to quit smoking by replacing some of the nicotine generally gained from cigarettes.[7] It decreases many of the physiological and psychomotor withdrawal symptoms usually experienced after smoking cessation and may thus enhance the chance of remaining abstinent.[8]

NRT products include chewing gum, transdermal patch, nasal spray, oral inhaler, and tablet.[4] The first product of NRT to become widely accessible was the chewing gum.[8] The Food and Drug administration (FDA) confirmed the prescription use of nicotine chewing gum as smoking cessation aid in 1984 and its nonprescription sale in 1995.[6]

The chewing gum is one of the new methods of oral transmucosal drug delivery and is a useful tool for systemic drug delivery.[9] Advantages of chewing gum over conventional drug delivery system include: Rapid onset of action, high bioavailability, easy consumption without the need of water, higher patient compliance, and fewer side effects like dry mouth and decrease in toxicity.[10] Formulations of medicated chewing gums may include active components, gum base, filler, softeners, sweetening agents, flavoring agents, and emulsifiers.[11] Medicated chewing gums are formulated to release the majority of their active component within 20–30 min. Factors such as intensity of chewing the gum and amount of saliva produced influence the drug release and absorption in the buccal cavity.[12]

In general, decrease in drug concentration upon dilution with saliva and its disappearance from buccal cavity due to unwanted ingestion are the disadvantages of medicated chewing gums. Chewing gums as a drug delivery system are, however, functional for medicines such as nicotine, caffeine, fluoride, dimenhydrinate, chlorhexidine, etc.[11]

Nicotine chewing gum is currently available in the market either as 2 or 4 mg preparations. The gums release a controlled amount of nicotine in mouth that is absorbed directly through the buccal mucosa, producing nicotine plasma concentrations which are about half that is produced by smoking a cigarette.[8] A limitation of commercially available nicotine gums is their slow rate of nicotine release and consequently the slow onset of their therapeutic effects.

The unpleasant taste of nicotine gums is, however, a major challenge with respect to the patients’ acceptance and compliance with suggested dosing regimens.[13] Thus, the present study was carried out to develop nicotine gums with improved taste and quality as a favorable dosage form for NRT. We formulated the gums using nicotine hydrogen tartrate due to its faster release rate. This may produce a more rapid onset of craving relief, and thus greater clinical benefits.[14]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

Nicotine tartrate was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. LLC. (Berlin, Germany). Elvasti, 487, Stick, and Fruit C gum bases were obtained from Gilan Ghoot Company, (Rasht, Iran). Flavors of eucalyptus, peppermint, banana, cola, and cinnamon were gifted by Goltash Company, (Isfahan, Iran), and flavors of cherry, tutti-frutti and raspberry by Farabi Pharmaceutical Company, (Isfahan, Iran). Sugar, glycerin, sodium saccharin, aspartame, stevia, zinc acetate, sodium acetate, and sodium chloride were of pharmaceutical grade.

Preparation of nicotine chewing gum

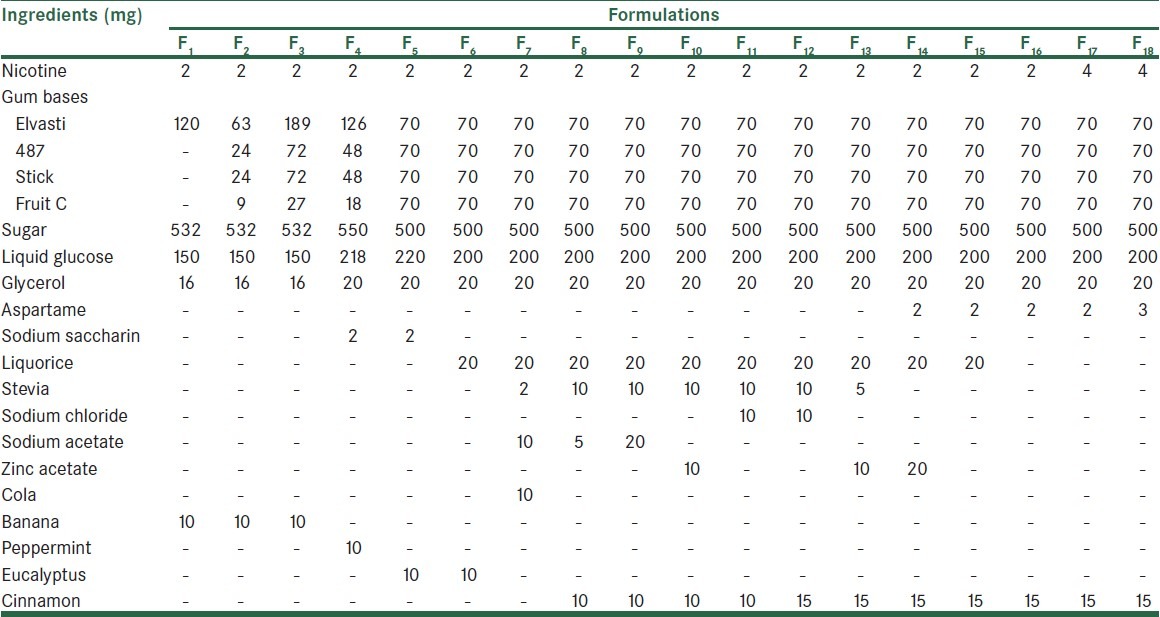

The nicotine gum was formulated using the gum bases, sugar, liquid glucose, glycerin, a sweetener (aspartame, stevia, liquorice, or sodium saccharin), a taste-masking material (zinc acetate, sodium acetate, or sodium chloride), and a flavoring agent. The mixture of gum bases was softened at 60°C. Nicotine tartrate, sugar, liquid glucose, glycerin, and other ingredients [Table 1] were added to the base to which was finally added the flavor at 40°C. The uniform mixture was cut into the pieces of suitable shape and size and kept at room temperature for 48 h [Table 1]. The medicated gums so prepared were coated by acacia aqueous solution (2% w/v). Sugar dusting followed by acacia–sugar–calcium carbonate coating was carried out until a smooth surface was produced.

Table 1.

Formulations of nicotine chewing gum with different ingredients

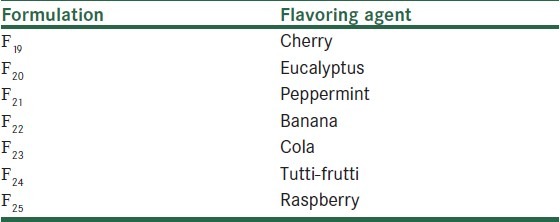

All formulations were preliminary investigated for considering the effect of different flavoring agents on masking the bitter taste of nicotine. Selected formulations according to organoleptic characteristics were prepared by using flavoring of cherry, eucalyptus, peppermint, banana, cola, tutti-frutti, and raspberry [Table 2].

Table 2.

Formulations of nicotine chewing gum by altering the flavoring agent in the formulation F16

Weight variation

Ten chewing gums of each formulation were weighed. The average weight and standard deviation were calculated.[15]

Uniformity of content

Ten nicotine gums were selected randomly.[16] Each gum was first dissolved in 50 ml chloroform. Phosphate buffer pH 6.8 was then used to extract drug into the aqueous phase. The amount of nicotine was determined by measuring the drug absorbance at 260.8 nm using a Shimadzu UV-1240 model UV-visible spectrophotometer. The experiment was repeated three times. The standard curve of nicotine tartrate was linear [y = 0.0198x + 0.0089 (R2 = 0.9995)] at concentrations ranging 5–60 μg/ml.

In vitro drug release

A mastication device which simulated the mastication of chewing gum in human was used to perform the drug release study. The device consisted of a piston which strokes the gum (60 strokes/min) at different points on a random base and a chamber which holds the gum and the release medium (pH 6.8 phosphate buffer). Water (37°C) was circulated through a jacket around the receiver chamber to simulate the in vivo temperature.[17]

Aliquots of 1 ml were removed at 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, and 45 min, and their absorbance were measured at 260.8 nm, as described before. The test was repeated three times.

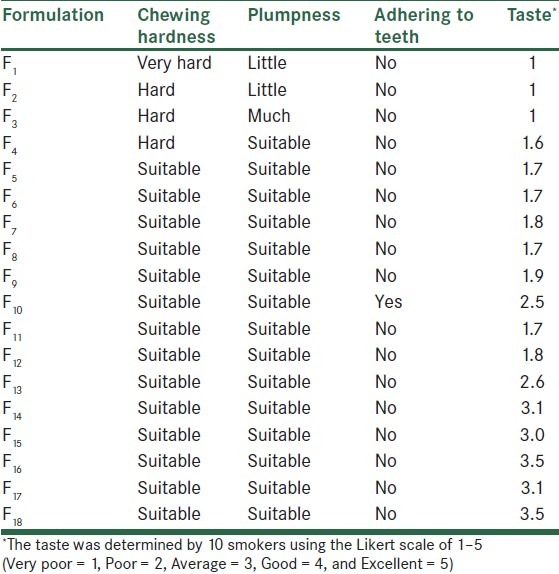

Evaluating the organoleptic characteristics of nicotine chewing gums

The Latin Square design was used for the preliminary evaluation of organoleptic characteristics of the formulations. Ten smokers were asked to chew each gum (F1–F18 formulations) for 20 min and express their opinions about chewing hardness, gum adhering to teeth, the plumpness, and the taste, according to the Likert scale of 1–5 (very poor = 1, poor = 2, average = 3, good = 4, and excellent = 5). The subjects were asked to rinse their mouths with water and wait for 20 min before examining the next formulation.

Further development of formulations was performed by altering the flavoring agent in the formulation F16, indicated to be the most acceptable gum in the preliminary evaluation [Table 2]. A panel test consisting of 20 smokers also was used in the same manner as previously explained to evaluate acceptability of the formulations. In the last stage, two formulations, (F19, F20), shown to be more acceptable to patients in the previous study, were sugar-coated and given to a new group of 30 smokers and evaluated as before.

RESULTS

Chewing gums weight variation and nicotine content

Weight variation of gums was within the USP-recommended limit of ±5%. The mean drug content was 1.94 ± 0.085 for 2 mg and 3.87 ± 0.125 for 4 mg nicotine chewing gums, all satisfying the criteria commonly required by USP for solid dosage forms.

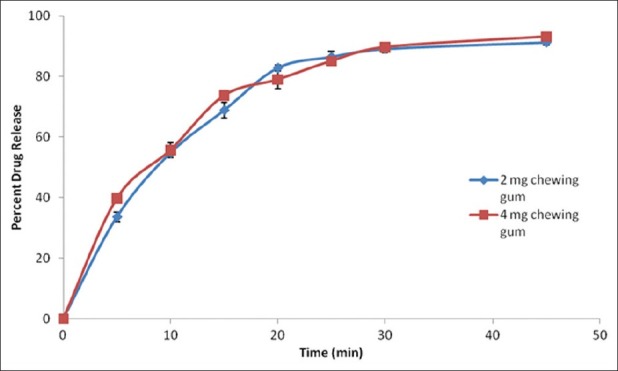

In vitro drug release from chewing gums

The release of nicotine from gum bases is shown in Figure 1. About 83% and 79% nicotine was released after 20 min from 2 and 4 mg gum, respectively. The drug release was, however, 92% and 93% from 2 and 4 mg formulations, respectively, after 45 min.

Figure 1.

In vitro release of nicotine from 2 and 4 mg chewing gum in pH 6.8 phosphate buffer at 37°C

Evaluation of organoleptic characteristics of nicotine chewing gum

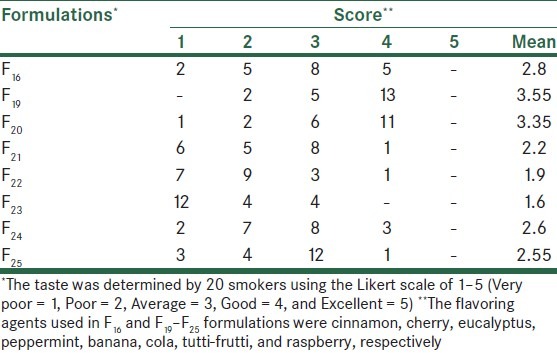

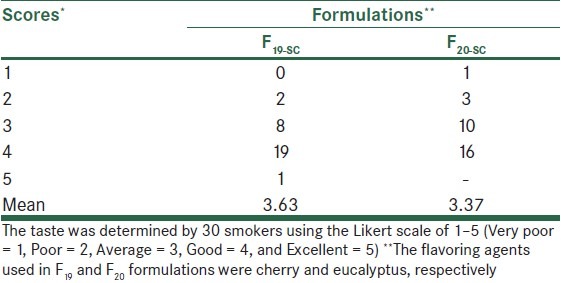

Organoleptic characteristics of nicotine gums were dependent on the ingredients used. F16 and F18 formulations (of 2 and 4 mg nicotine gums, respectively) exhibited acceptable physical characteristics with respect to chewing hardness, gum adhering to teeth, the plumpness, and the overall taste in preliminary evaluations [Table 3]. Further modification of formulation F16 using different flavoring agents indicated that cherry and eucalyptus (F19 and F20) were most efficacious in removing the bitter taste of nicotine gums [Table 4]. Sugar coating improved the appearance of gums; however, its effect on the taste was only marginal [Table 5].

Table 3.

Organoleptic characteristics of different nicotine chewing gums

Table 4.

Taste evaluation of formulations F16 and F19–F25 with different flavoring agents in nicotine gum formulations

Table 5.

The taste-masking effects of cherry or eucalyptus as flavoring agent in nicotine sugar-coated gum formulations

DISCUSSION

Nicotine gums can be considered as a dosage form which is provided to smokers, helping them quit smoking. To be demanded by patients, such medicated gums are required to have an optimal chewing volume, a long-lasting taste, anti-adherent properties to the teeth, and suitable organoleptic properties. Formulation F1 was very hard due to the nature of Elvasti base used. Elvasti, Stick, 487, and Fruit C bases have different hardness. Elvasti and Fruit C bases have the highest and the lowest hardness, respectively. In formulations F2–F4, by using three other bases, hardness of gum became less, but it was not suitable yet. In formulations F5–F25, softness and hardness of gum was desirable. In this study, for providing nicotine gum with suitable softness and hardness, equal ratios of Elvasti, Stick, 487, and Fruit C bases were used, but it is possible to use different ratios of these base in other medicated and non-medicated chewing gums.

Sodium saccharin with a sweetening power of 300–600 times higher than sucrose, though reported to enhance the effects of flavoring systems,[18] had little or no effect on masking the bitter taste of nicotine gums [Table 3] (F4 and F5). Liquorice, a sweetening agent which is widely used in tobacco industry,[19] decreased the bitterness of nicotine only slightly [Table 3] (F6). Similarly, sodium salts were not efficacious in masking the bitter taste [Table 3] (F7–F9 and F11–F12). This was not in agreement with other reports on the positive effects of sodium salts on the bitter taste improvement.[20]

Zinc acetate in formulations F10 and F13–F14 had a moderate effect in masking the bitterness of nicotine [Table 3]. It seems that zinc influences oral perception by eliciting the taste itself, interfering with the normal function of a taste system, and eliciting astringency.[21]

In our study, aspartame exhibited the strongest effect on modifying the bitter taste of nicotine gums [Table 3] (F16–F18). The amount of aspartame used seemed to be important too (compare F17 and F18) [Table 3]. The effect of aspartame was, however, reduced where other sweeteners were also added to the formulations [Table 3] (F14, F15).

The effects of various flavoring agents investigated through formulations F16 and F19–F25 [Table 4] indicated that cherry and eucalyptus produced the most pleasing taste (F19, F20). The overall effects of sweeteners and flavoring agents on taste modification seem to be dependent on the type of dosage form as well as active and inactive ingredients used in the formulation. While some have reported bitter taste modification of chlorhexidine chewing gums by aspartame, peppermint, and menthol,[17] others have seen better effect with sorbitol and peppermint.[15] However, in our study, peppermint showed an average effect on taste masking (compare F21 vs. F19 and F20) [Table 4]. Thus, it is rational to design and perform taste-modification investigations on each medication and dosage form independently.

Formulations F16 and F18 released 83% and 79% of their nicotine content within 20 min, respectively. This was in agreement with results obtained by Morjaria et al. on nicotine chewing gums, marketed as Pharmagum®S, Pharmagum®M, and Nicorette®.[22]

CONCLUSION

The results of this study showed that gum can be a good carrier of nicotine. The best formulations according to organoleptic characteristics were F16 and F18 for 2 and 4 mg gum, respectively. Aspartame and flavoring of cherry and eucalyptus were more effective to eliminate the bitter taste of nicotine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences as a thesis research project numbered 389366.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Mitrouska I, Bouloukaki I, Siafakas NM. Pharmacological approaches to smoking cessation. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20:220–32. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernhard D, Moser C, Backovic A, Wick G. Cigarette smoke--an aging accelerator? Exp Gerontol. 2007;42:160–5. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2006.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quit Smoking Support.com. [Updated 2012 January]. Available from: http://www. quit smoking support.com/whatsinit.htm .

- 4.Thomas E, Novotng TE, Cohen JC, Yarekli A, Sweanor D, Beyer J. Smoking cessation and nicotine-replacement therapies. In: Jha P, Chaloupka FJ, editors. Tabacco control in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 287–307. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yildiz D. Nicotine, its metabolism and an overview of its biological effects. Toxicon. 2004;43:619–32. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karnath B. Smoking cessation. Am J Med. 2002;112:399–405. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kralikova E, Kozak JT, Rasmussen T, Gustavsson G, Houezec JL. Smoking cessation or reduction with nicotine replacement therapy: A placebo-controlled double blind trial with nicotine gum and inhaler. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:433. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silagy C, Lancaster T, Stead L, Mant D, Fowler G. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation (Review) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD000146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madhav NV, Shakya AK, Shakya P, Singh K. Orotransmucosal drug delivery systems: A review. J Control Release. 2009;140:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biradar SS, Bhagavti ST, Hukkeri VI, Rao KP, Gadad AP. Chewing gum as a drug delivery system. Scientific Journal Articles. 2005. Available from: http://www.vipapharma.com/

- 11.Surana SA. Chewing gum: A friendly oral mucosal drug delivery system. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2010;4:68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowe RC. By gum a buccal delivery system - Private prescription: A thought-provoking tonic on the lighter side. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:617–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Britt DM, Cohen LM, Collins FL, Cohen ML. Cigarette smoking and chewing gum: Response to a laboratory-induced stressor. Health Psychol. 2001;20:361–8. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.5.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiffman S, Cone EJ, Buchhalter AR, Henningfield JE, Rohay JM, Gitchell GJ, et al. Rapid absorption of nicotine from new nicotine gum formulations. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2009;91:380–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pandey S, Goyani M, Devmurari V. Development, in-vitro evaluation and physical characterization of medicated chewing gum: Chlorhexidine gluconate. Der Pharmacia Lettre. 2009;1:286–92. [Google Scholar]

- 16.European Pharmacopoeia. 6th ed. Strasbourg: Directorate for the Quality of Medicine and Health Care of the Council of Europe; 2009. p. 278. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolahi Kazerani G, Ghalyani P, Varshosaz J. A study on design, formulation and effectiveness of chewing gum containing chlorhexidine gluconate in the prevention of dental plaque. J Dent Tehran Univ Med Sci. 2003;16:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoppu P. Saccharine sodium. In: Rowe RC, editor. Handbook of pharmaceutical excipients. 6th ed. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2009. pp. 608–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liquorice. Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. [Last Updated on 2012 Jan 27]. Available from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liquorice .

- 20.Ley JP. Masking bitter taste by molecules. Chem Percept. 2008;1:58–77. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keast RSJ. The effect of zinc on human taste perception. J Food Sci. 2003;68:1871–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morjaria Y, Irwin WJ, Barnett PX, Chan RS, Conway BR. In vitro release of nicotine from chewing gum formulations. Dissolut Technol. 2004;11:12–5. [Google Scholar]