Abstract

Background:

We conducted an epidemiological survey on seroprevalence of toxoplasma infection in women of childbearing age in Isfahan Province.

Materials and Methods:

In a cross-sectional study in 2010, 217 women in the age range of 10–50 years were randomly selected. The blood samples examined for the presence of IgG anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibody by a commercial ELISA kit (Dia-Pro, Milan, Italy). Chi-square and Fisher's exact tests were employed to examine the antibody status in different age, marriage, education, and residence groups.

Results:

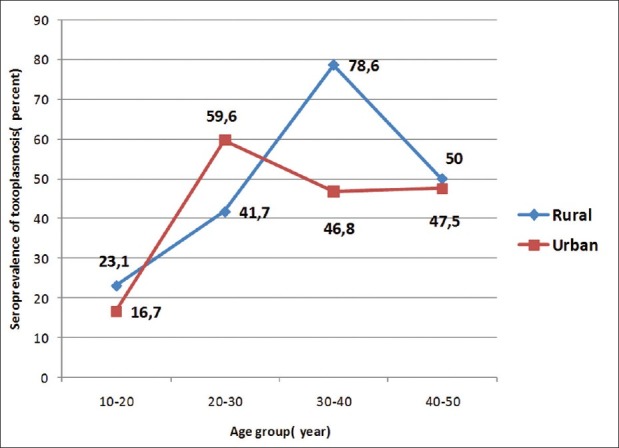

The overall prevalence was 47.5% (103/217). The peak age of infection acquisition was in the range 30–40 years in rural areas and 20–30 years in urban districts. There was no significant association between residence, education, and marriage groups on the one hand and chance of T. gondii infection on the other hand.

Conclusions:

The findings of the study suggest a moderate prevalence of T. gondii infection, but a high prevalence in ages of high reproductive activities.

Keywords: Childbearing age, Iran, prevalence, toxoplasmosis, women

INTRODUCTION

Toxoplasmosis is a worldwide infection, which can be acquired through the ingestion of tissue cysts in poorly cooked meat, inadvertent intake of sporulated oocysts excreted in cat feces, and transplacental route.[1] The infection in pregnant women is mainly asymptomatic and undiagnosed, but can be transmitted to the fetus and produce congenital infection. The risk of fetal transmission is about 25–65% and increases with gestational age at the time of maternal exposure, while the severity of the disease is related inversely to gestational age. [2] Severely infected infants could represent fever, hydrocephaly or microcephaly, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, convulsions, chorioretinitis (usually bilateral), and cerebral calcifications at birth.[2] These constitute a minority of the congenitally infected infants and most of them have no or mild symptoms at birth but show major sequels as chorioretinitis, strabismus, blindness, hydrocephaly or microcephaly, cerebral calcifications, developmental delay, epilepsy, or deafness in months or years later.[2] Toxoplasmic chorioretinitis in older children and adults usually is the result of congenital infection.[2]

To prevent congenital toxoplasmosis, it is necessary to determine the epidemiology and risk factors of the toxoplasma infection in women of childbearing ages. Therefore, the prevalence of fetal infection could be decreased in the community by implementing preventive measures in high-risk women and diagnosis and treatment of maternal infection at the early stages of the disease. There are many researches in prevalence of anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibody among Iranian women. The prevalence in highschool girls of Fasa, Isfahan, Tehran, and Bushehr cities was 10%, 17.5%, 17.76%, and 22.1%, respectively.[3–6] Among female students of the Persian Gulf University, the prevalence was found to be 11.5%.[7] In unmarried girls of Ghazvin,[8] Gorgan,[9] and Babol[10] the prevalence is estimated as 34%, 48.3%, and 63.9%, respectively. Many studies on seroprevalence of T. gondii infection have been performed in pregnant women who referred for a pregnancy test to a laboratory or for routine exams in an obstetric clinic. The seroprevalence was 19.2%, 27%, 27.6%, 32.7%, 33.5%, 37.8%, 44.8%, 45.5%, 48.3%, 54.2%, 74.6%, and 84% in Sabzevar,[11] Zahedan,[12] Chaharmahal o Bakhtiari,[13] Kkermanshah,[14] Hamedan,[15] Bushehr,[16] Ilam,[17] Karaj,[18] Rafsanjan,[19] Kashan,[20] Sari,[21] and Tehran,[22] respectively. In general, there is a decrease in the number of infected individuals from humid areas in north to dry provinces in central and south to mountainous regions in west Iran. Although these researches are helpful, they have been based on school, university, laboratory, hospital, or clinic samples that lack the statistical representation of the whole population of the women. Therefore, we performed a population-based cross-sectional study to determine the exact prevalence of T. gondii infection in women from rural and urban areas of Isfahan Province, central Iran, to identify characteristics of the individuals associated with seropositivity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

A total of 217 women in the age range of 10-50 years were randomly selected from among participants in a cross-sectional study performed in 2006 on hepatitis A. The sampling was performed by the multistage cluster sampling method in the entire population of Isfahan State.[23] The participants signed written informed consent to take part in epidemiological surveys. Sera were extracted from 5-ml venous blood samples collected from the participants. Isolated sera were frozen by the aliquot method and stored at -70ΊC until assay. A questionnaire including demographic, educational, and marriage status of the participants was filled and coded by trained interviewers at the time of blood sampling.Laboratory Method

After selection of the samples, frozen sera were liquefied at room temperature and tested for IgG anti-T. gondii antibody using a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (Dia-Pro, Milan, Italy). According to the recommendation of the kit, absorbance levels below 9 were considered as negative, 9 to 11 assumed as equivocal, and above 11 to be positive. The samples with equivocal results were retested and accordingly accepted as negative or positive. If the second test result was equivocal, the sample was excluded from the study.

The study was approved by the Regional Bioethics Committee of the Research Department of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

RESULTS

The overall prevalence of T. gondii infection was 47.5% (103/217). Table 1 shows the distribution of the participants in various age and residence groups. The distribution of age and residence was similar to that of the entire population in Isfahan Province in the year of the study.

Figure 1 illustrates seroprevalence of T. gondii infection in accordance to age and residence groups in studied population. The rate of seropositive women rose sharply from the age range 20–30 to 30–40 years in rural areas and 10-20 to 20-30 years in urban areas. The highest yearly increase in rural areas was 3.7% (in age range 30-40 years) and in urban regions was 4.29% (in age range 20-30 years). Accordingly, if we assume that each pregnancy lasts 9 months and if the moderate rate of fetal infection in each maternal infection were 40%, the theoretical estimate of congenital toxoplasmosis would be 1.1% in rural areas (in age range 30-40 years) and in urban regions this estimate was 1.29% (in the age range of 20–30 years).

Figure 1.

Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in women of child bearing are in Isfahan Province in accordance to age and residence groups

The seroprevalence in the age range 30–40 years shows a statistical difference in rural (11/14, 78.6%) and urban (22/47, 46.8%) areas (P = 0.036). There was no significant difference between other age groups and also between inhabitants of urban and rural areas in the remaining age groups.

Marital status (married versus single) in the age range 20–30 years has a significant effect on seroprevalence of T. gondii infection. Sixty-three percent (34/54) of married women versus 33.3 percent (5/15) of single women in the age range 20–30 years showed evidence of T. gondii infection (P = 0.041), while this difference in other age groups was insignificant. We assessed the effect of marriage in ages above 20 years by eliminating age as a confounder variable by Mantel–Haenszel common odds ratio estimate and found no significant effect for the variable.

Our data revealed no significant difference between the seroprevalence in educated (54.4%, 93/171) and uneducated (33.3%, 3/9) (P = 0.217), and also between levels of education in participants with ages above 20 years. The prevalence was 57.8% (26/45) in primary school (P = 0.179), 57.1% (20/35) in junior high school (P = 0.955), 53.8% (14/26) in high school, and 50.8% (33/65) in higher levels of education.

DISCUSSION

This study revealed a moderate infection rate (47.5%) with T. gondii protozoa in women of childbearing age in Isfahan Province, central Iran, in comparison with that in other countries and other states of Iran. Different investigations performed on pregnant women throughout the world show a wide spectrum of seropositivity. While higher prevalences of about 75–85% have been reported from Latin America,[24] central[25,26] and east Europe,[27] and Southeast Asia,[28] lower rates of near 20–30% are found in North America[29] and northern Europe.[30]

The prevalence we observed was approximately similar to those reported from Kerman[31] (46.9%), Ilam[17] (44.8%), Karaj[18] (45.5%), Rafsanjan[19] (48.3%), and Kashan[20] (54.2%); lower than northern cities[21] (74.6%) and Tehran[22] (84%); and higher than those in Sabzewar[11] (19.2%), Zahedan[12] (27%), Chahar mahal[13] (27.6%), Hamedan[14,32] (33.5%, 38.9%), Kerman shah[15] (32.7%), and Bushehr[16] (37.8%). These differences may be explained by climate conditions, nutritional behaviors, and keeping cats as pets, but the age of participants, other inclusion criteria, assay and sampling methods, and the year of the study may be other contributors. Because these studies included various groups of women (highschool girls, single, and pregnant) in different ages, they could not accurately predict the risk of congenital toxoplasmosis in the population studied. Our study clearly overcomes this problem and shows that most cases of primary infection in the studied population acquired at ages at which most conceptions occur (20–30 years in urban and 30–40 years in rural areas), so the rate of congenital toxoplasma infection (severe symptomatic to mild or nonsymptomatic at birth) in Isfahan Province should be high. If we consider the pattern of lifestyle and assume that the risk of primary infection does not change during pregnancy, our data analysis revealed the theoretical estimate of congenital toxoplasmosis as high as 1.1% in women aged 30–40 years in rural areas and 1.28% in women aged 20–30 years in urban areas of the province. Since most congenitally infected infants solely present the signs and symptoms of infection in future and this could be prevented or alleviated by early diagnosis and treatment during pregnancy or at birth, it could be very important to investigate this possibility in high-risk infants. Furthermore, warning and training women before pregnancy about the significance of the infection and offering preventive measures has paramount importance.

In our study, the seroprevalence in the age range 10-20 years (18.9%) is close to a previous study in highschool girls in Isfahan city[4] (17%) and other parts of Iran (10% in Fasa[3] and 17.7% in Tehran[5] cities). Lower prevalence in this age group remains many women vulnerable to primary infection during pregnancies at further ages [Figure 1] and increases the risk of congenital toxoplasmosis in the community. We recommend similar studies to be done in other parts to investigate high-risk women for primary toxoplasma infection and to plan the most appropriate method for prevention of congenital infection.

The seroprevalence in the age range 40–50 years in rural areas and 30–50 years in urban districts is lower than that observed in previous age groups [Figure 1]. These differences might be related to changes in nutritional pattern and behaviors in subsequent generations or the frequency of the infection in intermediate hosts.

Married women in the age range 20-30 years have a higher seroprevalence than unmarried women. It seems that changes in nutritional pattern and behaviors after marriage can increase exposure of women to T. gondii parasite. After marriage, most women in Iran have responsibilities for preparing meals, which can expose them to infective meat and vegetables. The marriage has no effect on seroprevalence in groups of higher ages. In some researches performed in various parts of Iran, the seroprevalence rates in single women aged 10–40 years (34% in Ghazvin,[8] 48.2% in Gorgan,[9] and 63.9 in Babol[10] ) were higher than those in single girls aged 10–20 years (10% in Fasa,[3] 17% in Isfahan,[4] and 17.7% in Tehran[5] cities). This may be due to involvement in food preparation activities in single women aged 20–30 years.

Our research elucidate the residence area (rural versus urban areas) has no effect on seroprevalence of toxoplasma infection. Other studies in Cuba,[33] Denmark,[34] and Sweden,[35] as well as in northwestern[8] and northern[9,36] Iran, were in favor of this result.

Despite other reports in inverse relationship between education and T. gondii infection,[8,9,12,32] we found no significant correlation. Interestingly, the prevalence in the educated group (54.4%) was higher than that in the uneducated group (33.3%).

CONCLUSION

This study suggests a moderate prevalence of T. gondii infection in Isfahan State and a high primary infection in reproductive ages necessitating an active strategy for the prevention of congenital toxoplasmosis in the province.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study has been performed by a grant from Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors are grateful to Mr. Ahmad Reza Pahlevan and Ms. Parisa Shoaei for their unsparing assistance in laboratory performance of the research.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Montoya JG, Boothroyd JC, Kovaks JA. Toxoplasma gondiis. In: Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dolin R, editors. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2010. pp. 3495–526. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer KM, Remington JS, McLeod R. Toxoplasmosis. In: Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler GJ, Sheldan K, editors. Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. Philadelphia PA: Saunders; 2004. pp. 2755–61. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatam Gh, Shamseddin A, Nikouee F. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasmosis in High School Girls in Fasa District, Iran. Iranian Journal of Immunology. 2005;2:177–81. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mahmoodi M, Izadi S, Mohebali M, Hejazi H. Seroepidemiological study on toxoplasmic infection among high school girls by IFA test in Esfahan city, Iran. Proceeding of 4th national congress of parasitology and parasitic diseases, Mashhad, Iran. 2003:388. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soleimani Z, Salekmoghadam A, Shirzadi M, Pedram N. Seroepidemiological study of toxoplasma gondi in high school girls in Robatkarim district by IFA and ELISA. Proceeding of 4th national congress of parasitology and parasitic diseases, Mashhad, Iran. 2003:387. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fouladvand M, Barazesh A, Naeimi B, Zandi K, Tajbakhsh S. Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in high school girls in Bushehr city South-west of Iran 2009. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2010;4:1117–21. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fouladvand M, Barazesh A, Naiemi B, Vahdat K, Tahmasebi R. Seroepidemiological Study of Toxoplasmosis in Girl Students from Persian Gulf University and Bushehr University of Medical Sciences. South Med J. 2011;2:114–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashemi HJ, Saraei M. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii in unmarried women in Qazvin Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2010;16:24–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharif M, Ajami A, Daryani A, Ziaei H, Khalilian A. Serological Survey of Toxoplasmosis in Women Referred to Medical Health Laboratory Before Marriage Northern Iran 2003-2004. Int J Mol Med Adv Sci. 2006;2:134–7. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Youssefi MR, Sefidgar AA, Mostafazadeh A, Omran SM. Serologic evaluation of toxoplasmosis in matrimonial women in Babol Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10:1550–2. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.1550.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moalaee H, shirzad E, Namazi MJ. Seroepidemiology of toxoplasmosis and its eye complication in pregnant women. Sabzavar Univ Med Sci J (Iran) 1999;8:21–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharifi Mood B, Hashemi Shahri M, Salehi M, Naderi M, Naser poor T. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma infection in the pregnant women in Zahedan, Southeast of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2006;6:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manouchehri Naeini K, Deris F, Zebardast N. The immunity status of the rural pregnant women in chaharmahal and bakhtyari province against toxoplasma infection 2001-2002. J Shahrekord Univ Med Sci. 2004;6:63–72. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Athari DV. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma antibodies among pregnant women in Kermanshah (Iran) Med J Islamic. 1973;25:93–6. Rep. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fallah M, Rabiee S, Matini M, Taherkhani H. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma infection in women aged 15–45 years in Hamadan west of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2003;3:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foladvand M, Jaafary SM. Seroprevalence of Anti-Toxoplasma antibodies in pregnant women in Bushehr. S Med. 1998;3:113–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abdi J, Shojaee S, Mirzaee A, Keshavarz H. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasmosis in pregnant women in Ilam Province Iran. Iran J Parasitol. 2008;3:34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keshavarz valian H, Nateghpour M, Zibaee M. Seroepidemiology of toxoplasmosis in Karaj Iran in 1998. Iran J Publ health. 1998;27:73–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keshavarz-valian H, Zare-ranjbar M. Toxoplasmosisin pregnant women and its transmision to foetus in Rafsanjan. J School Med Gilan (Iran) 1992;6:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arbabi M, Talari SA. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma infection in pregnant women in Kashan Iran. Feiz J. 2001;22:28–38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Safar MJ, Ajami A, Mamizade N. Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma infection in pregnant women in Sari. Mazandaran University Med Sci J (Iran) 1997;9:25–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medghalchi M. A dissertation for MSc. Tehran, Iran: Iran University of Med Sciences; 1991. The prevalence and incidence of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ataei B, Javadi AA, Nokhodian Z, Kassaeian N, Shoaei P, Farajzadegan Z, et al. HAV in Isfahan province A population-based study. Trop Gastroenterol. 2008;29:160–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spalding SM, Amendoeira MR, Klein CH, Ribeiro LC. Serological screening and toxoplasmosis exposure factors among pregnant women in South of Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2005;38:173–7. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822005000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jeannel D, Niel G, Costagliola D, Danis M, Traore BM, Gentilini M. Epidemiology of toxoplasmosis among pregnant women in the Paris area. Int J Epidemiol. 1989;17:595–602. doi: 10.1093/ije/17.3.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruiz Fons F, Vicente J, Vidal D, Höfle U, Villanúa D, Gauss C, et al. Seroprevalence of six reproductive pathogens in European wild boar (Sus scrofa) from Spain The effect on wild boar female reproductive performance. Theriogenology. 2006;65:731–43. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bobić B, Jevremović I, Marinković J, Sibalić D, Djurković-Djaković O. Risk factors for Toxoplasma infection in a reproductive age female population in the area of Belgrade Yugoslavia. Eur J Epidemiol. 1998;14:605–10. doi: 10.1023/a:1007461225944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Song KJ, Shin JC, Shin HJ, Nam HW. Seroprevalence of toxoplasmosis in Korean pregnant women. Korean J Parasitol. 2005;43:69–71. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2005.43.2.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones JL, Ogunmodede F, Scheftel J, Kirkland E, Lopez A, Schulkin J, et al. Toxoplasmosis-related knowledge and practices among pregnant women in the United States. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2003;11:139–45. doi: 10.1080/10647440300025512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cunningham FG, Macdonald FC, Gan NF. Williams obstetrics. 20th ed. Stamford UK: Appleton and Lange; 1997. pp. 1309–10. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keshavarz valian H, Mamishi S, Daneshvar H. Prevalevce of toxplasmosis in hospitalized patient of Kerman hospitals Iran. J Med Sci Kerman. 2000;7:126–39. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabiee S. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma infection in women aged 15–45 years in Hamadan west of Iran. J Res Health Sci. 2003;3:9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez Sanchez R, Bacallao Gordo R, Alberti Amador E, Alfonso Berrio L. Prevalence of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women of the province of La Habana. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao paulo. 1994;36:445–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lebech M, Larson SO, Peterson E. Occurrence of toxoplasmosis in pregnant women in Denmark A study of 5402 pregnant women. Ugeskar Laeger. 1995;157:5242–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ljungström I, Gille E, Nokes J, Linder E, Forsgren M. Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii among pregnant women in different parts of Sweden. 1995;11:149–56. doi: 10.1007/BF01719480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saeedi M, Veghari GR, Marjani A. Seroepidemiologic evaluation of anti-toxoplasma antibodies among women in north of Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2007;10:2359–62. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2007.2359.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]