Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of computer-assisted decision tools that standardize pediatric weight management in a large, integrated health care system for the diagnosis and management of child and adolescent obesity.

Study design

This was a large scale implementation study to document the impact of the Kaiser Permanente Southern California Pediatric Weight Management Initiative. An average of 739 816 outpatient visits per year in children and adolescents from 2007 to 2010 were analyzed. Height, weight, evidence of exercise and nutrition counseling, and diagnoses of overweight and obesity were extracted from electronic medical records.

Results

Before the initiative, 66% of all children and adolescents had height and weight measured. This increased to 94% in 2010 after 3 years of the initiative (P < .001). In children and adolescents who were overweight or obese, diagnosis of overweight or obesity increased significantly from 12% in 2007 to 61% in 2010 (P < .001), and documented counseling rates for exercise and nutrition increased significantly from 1% in 2007 to 50% in 2010 (P < .001).

Conclusions

Computer-assisted decision tools to standardize pediatric weight management with concurrent education of pediatricians can substantially improve the identification, diagnosis, and counseling for overweight or obese children and adolescents.

In the past 30 years, the prevalence of overweight and obesity has increased sharply in children and adolescents, with at least 18% of adolescents aged 12 to 19 years now considered obese.1,2 To address this dramatic increase, an expert committee with representation from 15 national organizations was convened by the American Medical Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2007 to recommend standardized approaches to the prevention and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity.3 This expert committee created guidelines that had clear steps for pediatricians and primary care physicians to take in healthcare settings, with additional recommendations made.4

A new set of Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) criteria now require valid assessment of height and weight, calculation of body mass index (BMI), and counseling for exercise and nutrition in all children and adolescents.5 HEDIS measures are used to compare key indicators of healthcare performance across health plans and are often used as benchmarks for efforts within healthcare organizations to improve the quality of care.

This study was conducted to evaluate the impact of an initiative including computer-assisted decision tools to standardize pediatric weight management in a large, integrated health care system for the diagnosis and management of child and adolescent overweight and obesity. The initiative was designed to address the expert committee guidelines and to ensure that the HEDIS requirements were met for assessment of overweight and obesity and exercise and nutrition counseling.

Methods

Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) is an integrated health care system that provides comprehensive health services for approximately 3.25 million residents of Southern California. Children and adolescents 2 to 17 years of age who had an outpatient visit in 2007, 2008, 2009, or 2010 were selected for analyses. Children and adolescents were socioeconomically diverse and broadly representative of the racial and ethnic groups living in Southern California, with 50% male, an age distribution of 25% from 2 to 5 years old, 29% from 6 to 11 years old, and 46% from 12 to 17 years old, and an ethnic distribution of 21% non-Hispanic white, 51% Hispanic, 7.5% non-Hispanic black, 6.8% Asian/Pacific Islander, 2.7% other/mixed race, and 12% unknown.2

The KPSC Pediatric Weight Management Initiative (KPSC initiative) began in 2008 and was designed to follow the expert committee guidelines. It created awareness in pediatricians and other primary care providers about the importance of child and adolescent overweight and obesity as a health concern and to assist them in documenting and managing the problem. The initiative began as the result of the implementation of a height and weight vital sign in the electronic medical record (EMR) in 2007. This made it easier to assess quickly the rates of overweight and obesity for the pediatric membership as a whole. The study was approved by the KPSC Institutional Review Board.

In 2008, the KPSC clinical practice guidelines for the management of pediatric weight were created by a group of pediatricians, pediatric specialists, health educators, and dieticians. The components of the clinical practice guidelines all followed the expert committee guidelines for the management of child and adolescent overweight and obesity3,6 and were designed to meet the newest HEDIS guidelines for weight assessment and exercise and dietary counseling for children and adolescents.5

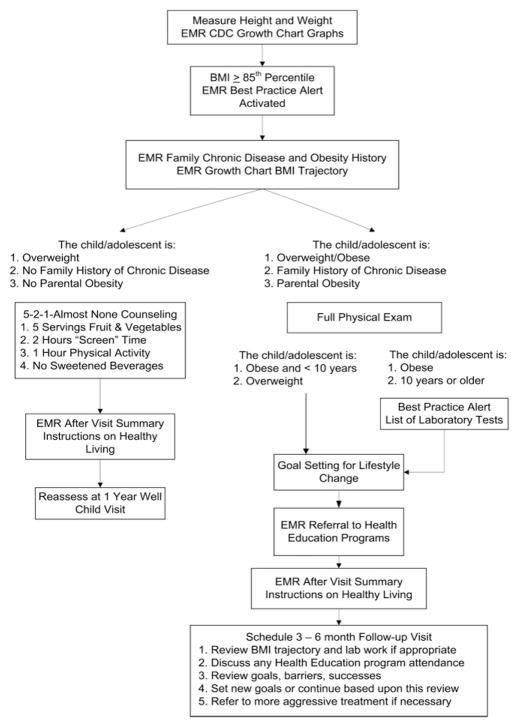

The elements of the KPSC clinical practice guidelines are shown in Figure 1 (available at www.jpeds.com). Although not explicitly stated in the clinical practice guidelines, pediatricians and primary care physicians were expected to diagnose overweight and obesity in children and adolescents and to use the HEDIS diagnosis codes for their exercise and nutrition counseling. These codes are a standardized set of specific International Classification of Disease, ninth/tenth revision (ICD 9/10) “V codes” used for diagnostic billing and are widely available in all medical practice settings.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the KPSC Pediatric Weight Management Initiative.

The KPSC EMR is based on a system created by Epic Systems Corporation (Madison, Wisconsin). It is a specific system commissioned by the organization and is called HealthConnect; however, all tools available in the KPSC EMR and the ability to implement these tools are available to other healthcare systems that use Epic systems. To assist pediatricians and primary care physicians in addressing the clinical practice guidelines and diagnostic and counseling goals, several enhancements were made to the EMR system by onsite information technology teams consisting of KPSC staff and Epic Systems staff.

First, when height and weight were entered in the EMR, they were automatically translated into BMI and BMI-forage percentiles and displayed as the CDC growth charts. Second, a “best practice alert” in the EMR was activated when a child or adolescent had a BMI >85th percentile for their age and sex. The alert provided reminders to the pediatrician and primary care physician about counseling and screening for related conditions, including laboratory tests. Finally, at the end of the visit, an application within the EMR allowed pediatricians and primary care physicians to refer patients to an internal health education program for family lifestyle change. In addition, there were a variety of prepared electronic documents called “after visit summaries” that could be printed out for the families that specified dietary and physical activity changes to do at home.

An online continuing medical education course was also developed to promote the use of the clinical practice guidelines and improve appropriate diagnosis and counseling documentation. This course summarized the health risks associated with obesity in childhood and adolescence, KPSC recommendations, and clinical practice guidelines and reviewed the steps for using the computer-assisted decision tools in the EMR. The course also provided guidance for a number of clinical practice behaviors, including how to have a conversation with parents about the weight of their child or adolescent by using the growth charts, how to assess a parent’s readiness for change, and how to set goals for changing family behavior with the 5-2-1-almost none tool available from Nemours.7,8 As of December 31, 2011, 33% of KPSC pediatricians had completed this course.

Analyses

All outpatient visits in years 2007, 2008, 2009, and 2010 for children and adolescents 2 to 17 years of age were selected for analyses. All outpatient visits were examined because the initiative targeted height and weight measurements, diagnosis, and counseling at every outpatient visit in primary care. Height, weight, and ICD 9/10 code diagnoses of overweight, obesity, exercise counseling, and nutrition counseling were extracted from the EMR.

The ICD 9/10 codes were extracted from the EMR. KPSC also uses ICD 9/10 code extensions to enable physicians to distinguish the degree of excessive body weight (overweight versus obesity) and the age at diagnosis (children or adolescents versus adults). These codes were as follows: 278.02B/D, V85.2 (adult overweight), 278.02E, V85.53 (child/adolescent overweight), 278.00C/E/F/G/Z, 278.01A/E, V85.3/4 (adult obesity), 278.00Y, V85.54 (child obesity), V65.41 (exercise counseling), and V65.3 (dietary counseling). Adult codes were extracted, because after preliminary review and discussions with pediatricians, it was apparent that primary care physicians and pediatricians were often using adult overweight and obesity codes to diagnose their patients. Exercise and nutrition counseling were only tracked with ICD 9/10 codes. No chart review was done to determine other documented counseling.

Errors in overweight and obesity diagnoses were defined as using adult codes of any kind or child codes that did not match the BMI percentile (ie, using a code for child obesity in an overweight child). Children and adolescents were divided in 3 categories for data analyses, overweight, moderately obese, and extremely obese, on the basis of the recommendations from the World Health Organization and CDC.9,10 We previously have published detailed findings on the distribution of overweight, moderate obesity, and extreme obesity in this population.11

χ2 analyses were used to compare children and adolescents with a height and weight measure to those children/adolescents without a height and weight measure for these demographics: sex, race/ethnicity, Medicaid status, and age. In addition, McNemar χ2 analyses were used to compare the rates of height and weight measurement and any diagnosis code for obesity or overweight and counseling between the years of 2007 and 2010. Data presented as a result of this comparison reflect the percentage of children and adolescents in a particular category who had a measure, were diagnosed, or were counseled. For example, in 2007, overweight or obese was diagnosed in 21% of all overweight or obese girls, whereas in 2010 this number had increased to 47%. All analyses were done in SPSS software (version 17.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois).

Results

An average of 1 976 872 outpatient visits per study year with an average of 739 816 children and adolescents per study year was analyzed. Most of these visits occurred in the departments of pediatrics (82%), and the remaining visits were in the departments of family medicine. Children and adolescents who had height and weight measured were similar in sex to those who did not have these measures (51% boys in both groups). However, children and adolescents with a height and weight measured were more likely to have Medicaid or other subsidized insurance coverage (21% versus 13%; P < .001) and to be 2 to 5 years old (24% versus 11%; P < .001) than those who did not have a height and weight measured. From 2007 to 2010, the prevalence of child and adolescent overweight and obesity was relatively stable, with 17% overweight, 14% moderately obese, and 7% to 9% extremely obese.

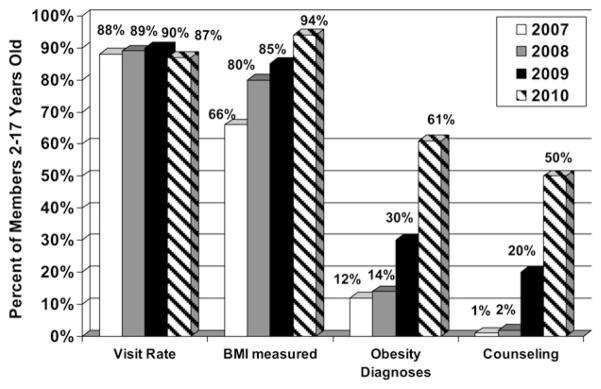

Figure 2 presents overall prevalence of height and weight measurement, any diagnosis of overweight or obesity, and any ICD 9/10 documented counseling across all children and adolescents. The frequency of diagnosis reflects the extent to which physicians used billing diagnosis codes for overweight and obesity and does not represent prevalence of overweight or obesity. Before the initiative, 66% of all children and adolescents who had an outpatient visit also had a height and weight measured, which increased to 94% after 3 years of the initiative (P < .001).

Figure 2.

Frequency of measurement of BMI, diagnosis of overweight and obesity, and exercise and nutrition counseling. The KPSC Pediatric Weight Management Initiative began in 2008. Visit rates are shown to illustrate that changes are not caused by increases in patient visits in the period of the initiative.

In children and adolescents who were overweight or obese, diagnoses for overweight or obesity increased from 12% in 2007 to 61% in 2010 (P < .001). The frequency of diagnosis rates increased across all sex, age, race/ethnicity, and Medicaid status subgroups (P < .001; Table). The increase was especially marked in overweight and obese children 2 to 5 years old (13%–75%) and in extremely obese children and adolescents across all ages (23%–75%). After the initiative, the use of correct diagnosis codes for overweight and obesity increased markedly for all age groups and weight categories (P < .001). Finally, the ICD 9/10 frequency of documented exercise and nutrition counseling in overweight and obese children and adolescents increased significantly from 1% in 2007 to 50% in 2010 (P < .001; Table). Counseling rates increased across all groups of overweight and obese children and adolescents, with an especially marked increase in children 2 to 5 years old (2% to 75%).

Table.

Diagnoses rates for overweight and obesity and documentation of exercise and nutrition counseling for overweight and obese children and adolescents before and after 3 years of the KPSC Child and Adolescent Weight Management Initiative

| 2007 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients in whom overweight and obesity diagnosed | ||

| Sex | ||

| Girls | 21% | 47%* |

| Boys | 21% | 53%* |

| Ethnicity/race | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 14% | 52%* |

| Non-Hispanic black | 24% | 63%* |

| Hispanic | 24% | 64%* |

| Other/unknown | 16% | 61%* |

| Medicaid or other subsidized program | 26% | 66%* |

| Age group | ||

| 2–5 years old | 13% | 77%* |

| 6–12 years old | 42% | 57%* |

| 13–18 years old | 51% | 56%* |

| Weight status | ||

| Overweight | 13% | 54%* |

| Moderately obese | 24% | 62%* |

| Extremely obese | 23% | 75%* |

| Rates of correct overweight/obesity diagnosesz | ||

| Overweight | ||

| 2–5 years old | 54% | 81% |

| 6–12 years old | 52% | 82% |

| 13–18 years old | 44% | 80% |

| Moderately obese | ||

| 2–5 years old | 68% | 80% |

| 6–12 years old | 63% | 82% |

| 13–18 years old | 42% | 76% |

| Extremely obese | ||

| 2–5 years old | 68% | 85% |

| 6–12 years old | 55% | 86% |

| 13–18 years old | 34% | 75% |

| Rates of counseling for exercise or nutrition | ||

| Sex | ||

| Girls | 3% | 50%† |

| Boys | 2% | 50%† |

| Ethnicity/race | ||

| Non-Hispanic white | 2% | 41%† |

| Non-Hispanic black | 2% | 51%† |

| Hispanic | 3% | 52%† |

| Other/unknown | 2% | 51%† |

| Medicaid or other subsidized program | 3% | 54%† |

| Rates of counseling for exercise or nutrition | ||

| Age group | ||

| 2–5 years old | 2% | 75%† |

| 6–12 years old | 3% | 45%† |

| 13–18 years old | 3% | 41%† |

| Weight status | ||

| Overweight | 2% | 48%† |

| At 6 months of age moderately obese | 4% | 49%† |

| Extremely obese | 5% | 56%† |

Diagnoses rates of overweight and obesity were significantly higher in 2010 than 2007 (P < .001).

Documentation rates of nutrition and physical activity counseling were significantly higher in 2010 than 2007 (P < .001).

Correct overweight/obesity diagnoses were defined as only using child codes and codes that matched the BMI percentile.

Discussion

This large-scale implementation study found that a clinical pediatric weight management initiative with EMR computer-assisted decision tools for child and adolescent obesity management resulted in substantial increases in a number of physician behaviors: the documentation of height and weight, the accurate diagnosis of overweight and obesity, and documentation of counseling for exercise and nutrition. This initiative was implemented by thousands of pediatricians and primary care physicians reaching >700 000 children annually. Before implementation, the frequency of diagnosis and counseling for child and adolescent overweight and obesity was similar to that found in the literature.12–17 Most of this earlier work had examined self-reported behavior from surveys of pediatricians and other healthcare providers. Three studies examined patient medical records.13,16,17 Of these 3 studies, BMI was documented in 1% to 22% of patient records, with diagnosis of obesity ranging from 10% to 53% and documentation of counseling for healthy behaviors ranging from 6% to 69%.

Few studies have reported the effect of an intervention to improve the diagnosis and management of child and adolescent obesity.17,18,19 Baillargeon et al19 describe a large initiative targeting adult obesity in primary care, which included continuing medical education, references and tools on a website, and monthly forums at which practitioners could exchange information. However, no results of the initiative were presented. Hinchman et al18 described a two-session continuing medical education training conducted at Kaiser Permanente Georgia very similar to that designed for the KPSC initiative, with the addition of a self-history form for the parents and a prescription pad that was used for behavioral contracting. Practice behaviors extracted from chart reviews compared a control group of pediatricians with pediatricians who completed the training. The training significantly increased the documentation of BMI and BMI percentile in the chart. No overweight or obesity diagnoses or documentation of counseling were assessed. The self-history form was used for many well-child visits (43%), but the prescription pad was used infrequently (6%).

Rattay et al7 used EMR tools in their Delaware primary care clinic initiative. These tools were very similar to those used in the KPSC initiative, including the automatic calculation of BMI and BMI percentile and a best practice alert when a child was identified as overweight or obese prompting the physician to make a diagnosis, order laboratory orders, make referrals, and conduct a family history and chronic disease assessment. In addition, there was an after-visit tip sheet on simple changes the family could make in their health habits and links to community-based resources that the pediatrician could give to families.

Different from the KPSC initiative, the Delaware efforts included pre-defined text embedded in the EMR for an assessment of readiness to change and for counseling of healthy behaviors. In addition to these tools, families were given the Nemours 5-2-1-almost none assessment tool8 while they were waiting for their appointments, and this was used to guide the pediatrician’s behavioral counseling. There was no reported evaluation of this initiative other than a statement by the authors that after 1 year of implementation, physicians had documented counseling for healthy behaviors during 97% of all well-child visits.

Despite the improvements seen with the KPSC initiative, there are a number of limitations with the design of its evaluation. Because a control group of pediatric practices independent of the initiative was not possible, it is not certain that the improvements of height and weight measurements, diagnoses of overweight and obesity, and counseling are caused by the initiative alone. The HEDIS requirements for documenting BMI and counseling may partially explain an increase in these metrics. In addition, secular trends suggest that there have been improvements in child and adolescent obesity management in primary care in the last 5 to 10 years,20,21 although there has not been an attempt to assess whether this occurred as a result of systematic implementation of initiatives. Another limitation of the study was that the true rate of exercise and nutrition counseling may be underestimated because progress notes were not reviewed. Although chart abstraction and manual examination of progress notes may be a better indicator of actual practice behavior than self-reports, it is extremely time consuming and cannot be used to examine aggregate practice patterns in large primary care networks serving approximatly 1 000 000 children and adolescents.

The prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents at KPSC did not change during the period of the initiative. The prevalence is similar to the race-specific national trends during this same period.10 Although the ultimate goal of the KPSC initiative is to eventually improve the prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents and ameliorate its health consequences, this is only after the initiative has been implemented fully for several years. Implementation was incremental for BMI documentation, diagnosis, and counseling from 2008 to 2010, with implementation rates varying from 94% (measurement of height and weight at every outpatient visit) to 50% (documentation of counseling). In addition, we found that children and adolescents with heights and weights recorded were more likely to be on subsidized insurance, such as Medicaid, and to be 2 to 5 years old. These two groups of children and adolescents are likely to be measured more often because of the promotion of annual well child visits, especially in the underserved community. Thus, the evaluation of the effect of the initiative on the entire KPSC population of overweight and obese children and adolescents is premature at this time.

Despite the importance of child and adolescent weight management in primary care settings, various studies demonstrate that primary care practitioners are not consistently following the formal expert committee guidelines.3,4,12 Primary care practitioners cite multiple barriers to providing care consistent with the recommendations. These barriers include a lack of tools or resources, lack of time during the clinic visit, competing priorities during the clinic visit, low reimbursement for time invested in counseling patients and families, lack of knowledge and skills to feel comfortable counseling, and a lack of awareness of resources outside the clinic.12,20,22,23 This study demonstrates that some of these barriers can be overcome with the implementation of computer-assisted decision tools in the EMR and concurrent education.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (grant to C.K. and partial salary support to K.C.).

Glossary

- BMI

Body mass index

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- EMR

Electronic medical record

- HEDIS

Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set

- ICD 9/10

International Classification of Disease, ninth/tenth revision

- KPSC

Kaiser Permanente Southern California

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:242–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koebnick C, Smith N, Coleman KJ, Getahun D, Reynolds K, Quinn VP, et al. Prevalence of extreme obesity in a multiethnic cohort of children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010;157:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lumeng JC, Castle VP, Lumeng CN. The role of pediatricians in the coordinated national effort to address childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;126:574–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Quality Assurance. [Accessed Jan 1, 2011.];HEDIS and Quality Measurement. Available at http://www.ncqa.org/tabid/59/Default.aspx.

- 6.Krebs NF, Jacobson MS. Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2003;112:424–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.2.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rattay KT, Ramakrishnan M, Atkinson A, Gilson M, Drayton V. Use of an electronic medical record system to support primary care recommendations to prevent, identify, and manage childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2009;123(Suppl 2):S100–7. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1755J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NEMOURS. [Accessed Jan 1, 2011.];5-2-1 almost none. Available at: http://www.nemours.org/service/preventive/nhps/521an.html.

- 9.World Health Organization. Technical report series 894: obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flegal KM, Wei R, Ogden CL, Freedman DS, Johnson CL, Curtin LR. Characterizing extreme values of body mass index for age by using the 2000 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1314–20. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koebnick C, Smith N, Coleman KJ, Getahun D, Reynolds K, Quinn VP, et al. Prevalence of extreme obesity in a multiethnic cohort of children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010;157:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rausch JC, Perito ER, Hametz P. Obesity prevention, screening, and treatment: Practices of pediatric providers since the 2007 expert committee recommendations. Clin Pediatr. 2011;50:434–41. doi: 10.1177/0009922810394833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazorick S, Peaker B, Perrin EM, Schmid D, Pennington T, Yow A, DuBard CA. Prevention and treatment of childhood obesity: care received by a state Medicaid population. Clin Pediatr. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0009922811406259. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dilley KJ, Martin LA, Sullivan C, Seshadri R, Binns HJ. Identification of overweight status is associated with higher rates of screening for comorbidities of overweight in pediatric primary care practice. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e148–55. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook S, Weitzman M, Auinger P, Barlow SE. Screening and counseling associated with obesity diagnosis in a national survey of ambulatory pediatric visits. Pediatrics. 2005;116:112–6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien SH, Holubkov R, Reis EC. Identification, evaluation, and management of obesity in an academic primary care center. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e154–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dorsey KB, Wells C, Krumholz HM, Concato J. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of childhood obesity in pediatric practice. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:632–8. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hinchman J, Beno L, Dennison D, Trowbridge F. Evaluation of a training to improve management of pediatric overweight. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;25:259–67. doi: 10.1002/chp.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baillargeon JP, Carpentier A, Donovan D, Fortin M, Grant A, Simoneau-Roy J, et al. Integrated obesity care management system-implementation and research protocol. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:163. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Small L, Anderson D, Sidora-Arcoleo K, Gance-Cleveland B. Pediatric nurse practitioners’ assessment and management of childhood overweight/obesity: results from 1999 and 2005 cohort surveys. J Pediatr Health Care. 2009;23:231–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delgado-Noguera M, Tort S, Bonfill X, Gich I, Alonso-Coello P. Quality assessment of clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of childhood overweight and obesity. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:789–99. doi: 10.1007/s00431-008-0836-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soderlund LL, Nordqvist C, Angbratt M, Nilsen P. Applying motivational interviewing to counselling overweight and obese children. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:442–9. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jansink R, Braspenning J, van der Weijden T, Elwyn G, Grol R. Primary care nurses struggle with lifestyle counseling in diabetes care: a qualitative analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]