Abstract

Objective

This qualitative study addresses: 1) What challenges do parents of overweight adolescents face? 2) What advice do parents of overweight adolescents have for other parents?

Design

One-on-one interviews were conducted with 27 parents of overweight or previously overweight adolescents

Setting

Medical clinic at the University of Minnesota

Participants

27 parents of adolescents (12-19 years) who were either currently or previously overweight recruited from the community Main Outcome Measures. Qualitative interviews related to parenting overweight adolescents

Analysis

Content analysis was used to identify themes regarding parental experiences.

Results

Issues most frequently mentioned: 1) uncertainty regarding effective communication with adolescent about weight-related topics, 2) inability to control adolescent’s decisions around healthy eating and activity behaviors, 3) concern for adolescent’s well-being, 4) parental feeling of responsibility/guilt. Parental advice most often provided included: 1) setting up healthy home environment, 2) parental role modeling of healthy behaviors, and 3) providing support/encouragement for positive efforts.

Conclusions

Topics for potential intervention development include communication and motivation of adolescents regarding weight-related topics, appropriate autonomy, and addressing negative emotions concerning the adolescent’s weight status. Targeting these topics could potentially improve acceptability and outcomes for treatments.

Keywords: adolescence, parenting, obesity, overweight

INTRODUCTION

The high prevalence and steady increases in overweight and obesity among adolescents over the past 30 years are of significant public health concern.1 Overweight and obese adolescents have an increased risk for physical comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes, and negative psychosocial consequences stemming from the stigma associated with being overweight. 2 Additionally, overweight and obese adolescents are at a significant increased risk for obesity in adulthood. 3-5

Most treatment studies of overweight and obese youth have focused on the pre-adolescent age range,6,7 and fewer have focused on adolescents.8,9 It can be challenging to know how to involve parents in interventions for adolescents because of issues related to developing autonomy and increasing independence. Parents of overweight and obese adolescents often find themselves in a dilemma. On one hand, parents may be concerned about their adolescent’s health, the psychosocial stigmas, and the negative physical consequences associated with being overweight or obese. On the other hand, parents also recognize their adolescent’s need for autonomy. Thus, parents may struggle with what to say or do to best help their adolescent manage their weight.

Parents have an important role in helping their children and adolescents to adopt healthy behaviors.10,11 Mechanisms by which parents may influence eating habits and behaviors include family meals,12-15 food availability at home,16-18,19 and discussing or encouraging dieting.20-24 Mechanisms by which parents can influence physical activity levels are parent modeling physical activity behavior25,26 and support for children’s physical activity.27,28 Unfortunately, providing this type of support can be challenging for families and become especially difficult when coupled with an adolescent’s development of autonomy. It is important to develop a greater body of knowledge related to parenting overweight and obese adolescents, to ultimately inform interventions.

To the best of our knowledge, only one published qualitative study 29 has explored experiences of parenting an overweight child. Jackson and colleagues interviewed mothers of overweight youth (ages 14 months – 15 years) about their experiences in parenting. The study found that mothers often felt judged and blamed for their child’s weight status, were frustrated with how to best help their child, and worried about their child’s future. Additionally, the mothers all identified modeling healthy behaviors as a strategy for helping their children. Although the Jackson study has highlighted some of the issues that parents face when they have an overweight children, this study recruited parents of youth from a wide age range. Considering the challenges with parenting adolescents in general, it is important to identify issues specifically faced by parents of overweight adolescents, to identify potential targets for interventions. The current study addresses this gap in the literature by posing two research questions: 1) What issues do parents of overweight adolescents face? and 2) What advice do parents of overweight adolescents have for other parents?

METHODS

Participants

Parents of adolescents were recruited from a larger study entitled Successful Adolescent Weight Losers (SAL) 30 that surveyed adolescents (ages 12-17 years) and their parents to determine factors contributing to successful weight loss among adolescents. Two groups of adolescents were recruited for SAL study; overweight and obese adolescents who lost weight and those who did not. Inclusion criteria for the adolescent weight loss group included a self-reported loss of at least 10 pounds in the past 2 years, maintenance of the weight loss for at least 3 months, and overweight or obese status (>85% sex- and age adjusted body mass index [BMI] percentile) before weight loss. Inclusion criteria for the comparison group included overweight or obese status (>85% sex- and age-adjusted BMI percentile) and no reported weight loss within the past 2 years. Adolescents were excluded from the study if they had ever been diagnosed with an eating disorder or had any physical or psychological condition (i.e. cancer, depression, etc) that could impact weight. Parental interviews were conducted with 26 mothers and 1 father. The average age of the parents was 47.5 years, and 74% identified themselves as Caucasian, 19% as Native American, and 7% as African American. Fifteen percent of parents had an income less than $20,000; 7% of parents had an income between $20,000-$40,000; 19% of parents had an income of $40,000-$60,000; 45% of parents had an income over $60,000; 14% of parents did not report their income. Of the mothers interviewed, 20 had female adolescents and 6 had male adolescents. The one father interviewed had a female adolescent. All parents lived in the Minneapolis/St. Paul metropolitan area. Fourteen interviews were with parents whose adolescent did not lose weight (adolescent mean BMI percentile = 97.5%), and thirteen interviews were conducted with parents whose adolescent had successfully lost 10 pounds and kept it off for 3 months (adolescent mean BMI percentile = 87.2%). Twenty-two percent of the sample (6 adolescents) reported that the worked with a dietitian. Initially, the two parent groups were analyzed separately to examine similarities and differences in responses between the groups. As the interviews were analyzed, no remarkable differences were noted in responses between the parents of adolescents who lost weight and those who did not: therefore these groups were combined for final analysis.

Procedures

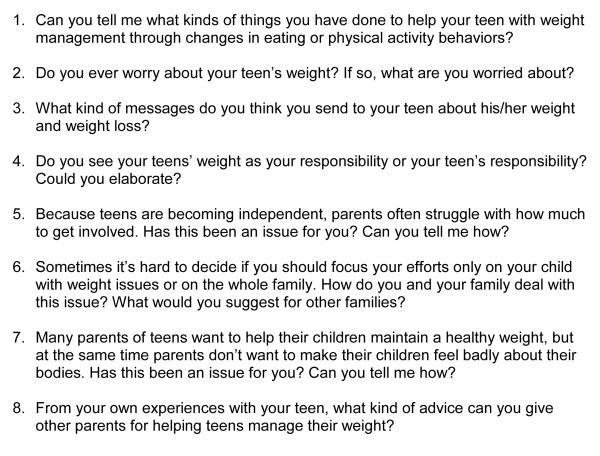

One-on-one interviews were conducted with parents at a medical clinic at the University of Minnesota. Questions were formulated and piloted with a few parents prior to beginning the study. Two trained researchers conducted interviews using standardized interview questions. Parents were asked eight broad questions to explore their experiences in parenting an overweight adolescent (Figure 1). Interview questions addressed parents’ attempts to help adolescents manage their weight, issues parents of overweight and obese adolescents face, and advice parents have for other parents. Additional probing questions were used at the interviewers’ discretion to obtain more information from participants when necessary or to clarify participant responses. Interviews were audio-taped and varied in length, averaging 30-45 minutes. Tape-recorded interviews were reviewed immediately to allow the interviewer to summarize and record impressions and note themes expressed by parents. Parents were selected on a rolling basis, until themes began to repeat themselves and theoretical saturation was reached. Informed consent was obtained from participants prior to the interviews. Interviews were conducted between December 2004 and November 2005 and study procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota Human Subjects’ Committee.

Figure 1.

Parent Interview Questions

Data Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim from audiotape and were then examined using content analysis techniques described by Miles and Huberman.31 Transcripts were reviewed using an inductive method to identify emerging themes. Two main themes, issues parents face and advice for other parents were identified from the interviews. Based on these themes a coding template was developed. Following discussion with the research team, a final coding template was developed and all interviews were analyzed in entirety to ensure all responses were captured whether or not in direct response to questions pertaining to parental issues or advice. All transcripts were double coded; once by the second author and once by an individual with expertise in the field of pediatric overweight that was not a part of the research team. Agreement between the two coders was calculated using the formula: number of agreements/total number of agreements plus disagreements.31 Inter-rater reliability was 90%. Discrepancies were discussed until total agreement was reached among interviewers.

RESULTS

Issues parents of overweight adolescents face

Participants (n=27) identified many issues related to parenting an overweight adolescent. Issues most frequently mentioned by parents include lack of knowledge about how to communicate with adolescent about weight-related topics (n=15), an inability to control adolescent’s decisions or make decisions for their adolescent about eating or physical activity behaviors (n=14), a concern for adolescent’s well being (n=11), and parental feeling of responsibility for adolescent’s weight problems (n=10).

Communication with adolescent

Over half of parents discussed difficulty in communicating with their adolescent about eating or weight-related issues. Parents worried about being perceived as nagging or annoying, and several struggled with comments being misinterpreted by adolescents. One parent of a 15-year old girl stated: “…we’re very careful not to say anything to her that will set her off or that she can take as criticism.” Another mother of 15-year old girl commented, “I just feel like maybe I’m almost warning her too much because even last night she said ‘I’m sick of you telling me what to eat and what not to eat’. She’s tired of it. I feel like maybe I should back off.” A mother of a 17-year old girl commented “ I try to stress to her what she needs to do, she has to lose weight, do some activities…and if I try and tell her she just gets more annoyed.”

Parents also struggled with how to communicate the importance of changing eating or exercise habits without lowering their adolescent’s self-esteem, which was often already perceived as low. A parent of a 13-year old girl said, “I lived through my [older] daughters feeling insecure about their weight and just in trying to tell them that I think they need to exercise more, there were real strong reactions from the girls feeling very offended and hurt.”

Even parents whose adolescents had successfully lost weight still struggled with communication issues. One mother whose 18-year old daughter had lost weight commented, “It’s been more of an issue now, when she’s put some of the weight back on. You don’t want to say anything because she’ll just let you have it. Even though she had opened the door before on it, they have to decide for themselves. I think her dad actually said something to her once and she just tuned him out.”

Inability to control adolescent’s decisions

Parents also discussed frustrations with not being able to control their adolescent’s decisions about eating and physical activity. Parents struggled with not being with their adolescents all of the time, as well as not being able to force them to make changes in their eating or activity behaviors. Several parents commented that while they could encourage their adolescents to make good choices, there was a significant level of frustration in the loss of control experienced as their children became adolescents and strove for more autonomy. A mother of a 14-year old girl stated, “I’m trying to get her to get into more exercise, and I’ve got her on a diet, but I can’t be around her all the time.” She went on to say, “When she goes out of the house or out of my sight, she eats what she’s not supposed to eat.” The mother of a 17-year old girl mentioned similar frustrations, “I’m not with my child twenty-four seven, and if I’m not home and if it’s there, she’s going to help herself.” A mother of a12-year old girl said “I could pretty well control what she was eating as a smaller child. Now, less and less. Most nights we have dinner together. I will insist she at least try the vegetable, and that’s about as far as I feel I can realistically go with controlling it.”

Concern for adolescent’s well being

Parents also discussed their concerns for their overweight adolescent’s physical and mental health. Several parents felt conflicted in wanting their children to lose weight and be thinner because it would likely make life easier, despite knowing that a person’s weight was not something that defined who or what they are. Several parents, who were overweight themselves, wanted their adolescents to lose weight because they understood, firsthand, the physical and psychosocial consequences of being overweight, and didn’t want their children to go through a similar experience. A mother of a 19-year old girl commented, “Because I’m overweight myself, I just know how happy, much happier she would be if she’s not overweight, or she’s at a better weight, closer to where she wants to be. And I really just want that for her.” Another mother of a 15-year old female said “It’s hard, because in the way of the world, I think she could be happier if she wasn’t overweight. It bugs me because I just think that some of the things that she worries about wouldn’t be such a big worry if she was thinner.”

Parental responsibility

Many parents struggled with feeling responsible for their adolescent’s weight problems. Most parents commented that both parents and adolescents have a role in making healthy decisions, but often parents felt they should be doing more to instill healthy habits in their adolescents. One mother felt like she was responsible for her daughter being overweight and commented, “I feel like I almost gave her that problem because of the way I cook or the way I serve. I guess I blame myself a lot. Just thinking that if I would have done things differently, maybe she wouldn’t have that problem. I don’t know; I made it too available, made too much food.” A mother of a 13-year old female said “Most of the time we don’t eat together. And who’s responsible for that? Me. The mother is. I’ve just been very lackadaisical, and I know that my kids would benefit from more structured eating.”

Advice for other parents of overweight adolescents

Parents (n=24) talked about strategies they felt were or would be helpful or important and offered many suggestions for other parents to help adolescents lose weight and improve eating and exercise habits. Advice most often noted by parents included having a healthy home environment (n=15), role modeling healthy behaviors (n=12), and providing support and encouragement for positive efforts (n=9).

Healthy home environment

The majority of parents discussed the importance of having a healthy home environment to help adolescents with weight management. Parents believed setting up a household that supports a healthy lifestyle would have a positive effect on adolescents’ behaviors. Many parents discussed having fruits, vegetables, healthy snacks, and water available as one of the best ideas for setting adolescents up to be successful in changing eating habits and losing weight. Some parents also felt having exercise equipment available for adolescents at home was part of setting up a healthy home environment. The mother of a 17-year old female stated, “She wanted to join a gym, but it was too expensive. So we went out and got some videos and an exercise ball and then got a good quality treadmill too. So we have it all available at home when she wants to use it.” A mother of a 12-year old male said “I think it’s important to have healthy snacks available right away. I think just having healthy food ready so you don’t sabotage your child. Just have the healthy stuff available and not a lot of junk available in the house.”

Role modeling healthy behaviors

Parents also discussed the importance of modeling healthy behaviors, and suggested parents examine the eating and exercise behaviors they model to their children. Specifically, parents mentioned practicing what is being preached to adolescents and making sure that, as a parent, you are modeling healthy behaviors. The mother of a 13-year old female said, “I think my recommendation would be for teens to see parents participating too. If you eat differently and you exercise different than they are, it doesn’t mix.” A mother of a 13-year old female said “Parents need to be consistent in their own actions. That means don’t role model to the kids McDonald’s if you want them to be eating healthy salads.”

Providing support and encouragement

Several parents discussed providing encouragement and support for positive efforts towards healthy lifestyle behaviors being made by their adolescent. Parents felt positive feedback was important to maintaining their adolescent’s motivation to make healthy behavior changes. Some parents noted that adolescents may become frustrated with the lack of quick results with weight loss and they need to be encouraged to continue positive behaviors that over time will likely result in weight loss. A mother of an 18 year-old female commented, “I make sure to tell her when I notice the healthy behaviors she is doing. I know she wants to lose weight right now, but I know it won’t happen as fast as she wants it to. I think giving her good feedback about her eating more fruits and walking more helps her not give up.” A mother of a 12-year old female said “I think it’s more encouragement and praise when they’re doing things right. Kids need to hear that from their parents.”

DISCUSSION

This study examined issues faced by parents of overweight and obese adolescents and advice for other parents in similar situations. Issues raised by parents included: difficulties encountered in effectively communicating with their adolescent about weight-related topics, perceived inability to control adolescent’s decisions about eating and physical activity, concern for adolescent’s physical and mental well being, and feelings of personal responsibility for adolescent’s weight issues (Table 1). Parental advice for helping overweight adolescents included having a healthy home environment, modeling healthy behaviors, and providing encouragement and support to adolescents for positive behavior changes (Table 2).

Interestingly, many of the issues participants identified are similar to issues faced by parents of adolescents in general. For instance, communicating effectively about sensitive topics like alcohol and drug use is one struggle many parents face.32 Parents interviewed for this study may struggle with those same issues as well, but were additionally concerned about how to discuss weight issues with their adolescent. Most parents, whether their adolescent had lost weight or not, were unsure of when to bring up the subject of weight and furthermore, how far to push the subject once the subject was brought up with their adolescent. These findings corroborate findings by Pagnini and colleagues about the challenges in having productive, helpful, and non-judgmental conversations about weight with their children. 33 Parental advice for other parents of overweight adolescents appears to parallel and address the issues faced in parenting overweight adolescents. For instance, advice for parents to establish a healthy home environment and model healthy behaviors could be helpful in addressing feelings of responsibility for adolescent’s weight struggles and inability to control all of the adolescent’s decisions related to eating and activity. If parents have healthy foods available at home and are modeling healthy eating and exercise habits, they may be less likely to feel their own actions and lifestyle at home are to blame for their adolescent’s weight issues. Additionally, research shows that maternal concern for healthy eating is associated with both maternal and adolescent fruit and vegetable consumption.24 Similarly, parents may feel more confident in an adolescent’s decision-making ability about healthy eating and activity if they have done what they felt was possible in their own home and modeled healthy behaviors. Results from the current study are also similar to those of Booth and colleagues who interviewed parents of overweight youth and reported concerns by parents regarding the amount of control they had over weight related decisions their children make. 34 Parents felt they did have control over what foods were in the home. Data from the current study provide further support for quantitative findings showing the importance of parental modeling and home availability of healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables in adolescent’s intake 16,18 as well as qualitative studies with adolescents citing these factors as contributors to their food choices.17 Parental provision of healthy meals and modeling of healthy behaviors could assist their adolescent in engaging in these behaviors. The family meal is a time when parents have the opportunity to model healthy eating behaviors, but the frequency of family meals decreases throughout adolescence.27,28 In addition to the family meal providing an opportunity to serve as a role model, this is also a time for parents to communicate with their adolescent as well as provide support for positive behavior changes. 15

The current study provides initial data that support for healthy eating and physical activity behaviors for adolescents could come in the form of both “doing” and “talking”. Parents can think of these two categories as methods for influencing their adolescent’s weight. In terms of “doing”, parents can support their adolescent’s physical activity level by engaging in shared activities such as going on evening walks together, playing active games together, planning active family vacations, by watching their children perform in various sports activities, and by providing transportation to local recreational facilities. Parents can support their adolescent in eating more healthfully by providing a healthy home environment and modeling healthy eating behaviors.

In terms of “talking” about adopting healthier eating and physical activity behaviors, it is important for parents to remember that their adolescent could have a negative emotional response (i.e. sad or angry) when questioned about their weight. In the current study, and other studies,33,34 parents were aware of the psychosocial effects of being overweight. Therefore exploring other methods of addressing weight issues besides just focusing on weight loss may be needed when working with adolescents, such as being fit and physically active, or eating for health. Practitioners can help facilitate positive change within the home environment for the whole family instead of only focusing on the adolescent. In addition, given the issues about communication it is important that practitioners recognize these challenges and work to support and help both parents and adolescents. The current study has several strengths and limitations that deserve notation. This is the only study that we are aware of that explored parenting issues from the perspective of parents of overweight adolescents.

Through the use of one-on-one interviews, rich, in-depth information was gathered from parents about the specific issues they face on a day to day basis in parenting overweight adolescents. The interview format also allowed participants to expand upon responses, which created a greater understanding of parental issues. Limitations of the study include a small, self-selected sample size with limited diversity in gender and ethnicity that does not fully represent all population groups. Additionally, some of the adolescents in this study had lost some weight, however, the interviews did not reveal any differences in parental responses between parents of adolescents who lost weight and those who did not. Further research should expand on these findings with larger, more diverse populations.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH AND PRACTICE

Findings from this study reveal that parents of overweight and obese adolescents face many issues and have a wealth of information to help other parents facing similar issues. In terms of practice, study findings suggest that it may be helpful for healthcare providers to include family members in the treatment process as well as consider the adolescent’s level of autonomy and the context in which the adolescent fits into the family structure. It may be most helpful for health care providers to operate in a non-judgmental manner towards both an overweight adolescent and his/her parents as discussing weight may bring up negative emotions by both the adolescent and the parent. Findings from the current study further suggest that health care providers should emphasize that parents can set an example and model healthy behaviors both at home and away from home.

This study also provides a number of potential research targets. Many parents in this study interviewed struggled with effectively communicating with their adolescent about weight issues. It is possible that families could benefit from parenting groups for parents of overweight adolescents that target communication techniques about weight. Parents also expressed concerns regarding adolescent’s decisions regarding their weight, physical activity and eating behaviors and families may benefit from a focus on motivating their adolescents. In addition, parents in this study identified changes in the home food environment, modeling healthy behaviors, and using praise and support as advice for other parents in similar situations. Further development regarding interventions specifically for parents of overweight adolescents could enhance these points. As mentioned previously, larger studies with more diverse populations are needed.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant from the University of Minnesota Children’s Vikings Fund to K. Boutelle.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of high body mass index in US children and adolescents, 2007-2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine CoPoOiCaY, Food and Nutrition Board, Board on Health Promotion and Disease Prevention . Preventing Childhood Obesity: Health in the Balance. Washington DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srinivasan SR, Bao W, Wattigney WA, Berenson GS. Adolescent overweight is associated with adult overweight and related multiple cardiovascular risk factors: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Metabolism. 1996;45(2):235–240. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90060-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dietz WH. Childhood weight affects adult morbidity and mortality. J Nutr. 1998;128(2 Suppl):411S–414S. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.2.411S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year follow-up of behavioral, family-based treatment for obese children. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;264(19):2519–2523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilfley DE, Stein RI, Saelens BE, et al. Efficacy of maintenance treatment approaches for childhood overweight: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1661–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jelalian E, Lloyd EE. Adolescent obesity: assessment and treatment. Med Health R I. 1997;80(11):367–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jelalian E, Lloyd-Richardson EE, Mehlenbeck RS, et al. Behavioral weight control treatment with supervised exercise or peer-enhanced adventure for overweight adolescents. J Pediatr. 2010;157(6):923–928. e921. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindsay AC, Sussner KM, Kim J, Gortmaker S. The role of parents in preventing childhood obesity. Future Child. 2006;16(1):169–186. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, French S. Individual and environmental influences on adolescent eating behaviors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(3 Suppl):S40–51. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C, Casey MA. Factors influencing food choices of adolescents: findings from focus-group discussions with adolescents. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(8):929–937. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Frazier AL, et al. Family dinner and diet quality among older children and adolescents. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(3):235–240. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Videon TM, Manning CK. Influences on adolescent eating patterns: the importance of family meals. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(5):365–373. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00711-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burgess-Champoux TL, Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Are family meal patterns associated with overall diet quality during the transition from early to middle adolescence? J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(2):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.03.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Story M, Wall M. Associations between parental report of the home food environment and adolescent intakes of fruits, vegetables and dairy foods. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(1):77–85. doi: 10.1079/phn2005661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Dea JA, Caputi P. Association between socioeconomic status, weight, age and gender, and the body image and weight control practices of 6- to 19-year-old children and adolescents. Health Educ Res. 2001;16(5):521–532. doi: 10.1093/her/16.5.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell K, Crawford D, Salmon J, Carver A, S G, Baur L. Associations between the home food environment and obesity-promoting eating behaviors in adolescence. Obesity. 2007;15(3):719–730. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacFarlane A, Crawford D, Worsley A. Associations between parental concern for adolescent weight and the home food environment and dietary intake. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42(3):152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huon G, Lim J, Gunewardene A. Social influences and female adolescent dieting. J Adolesc. 2000;23(2):229–232. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulkerson JA, McGuire MT, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, French SA, Perry CL. Weight-related attitudes and behaviors of adolescent boys and girls who are encouraged to diet by their mothers. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002 Dec;26(12):1579–1587. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon R, Adair V, O’Conner S. Parental influences on the dieting beliefs and behaviors of adolescent females in New Zealand. J Adolesc Health. 1996;19:303–307. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schreiber G, Robins M, Striegel-Moore R, Obarzanek E, Morrison J, Wright D. Weight modification efforts reports by black and white preadolescent girls: National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. Pediatrics. 1996;98:63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boutelle KN, Birkeland RW, Hannan PJ, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. Associations between maternal concern for healthful eating and maternal eating behaviors, home food availability, and adolescent eating behaviors. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(5):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stucky-Ropp R, DiLorenzo T. Determinants of exercise in children. Prev Med. 1993;22:880–889. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore LL, Lombardi DA, White MJ, Campbell JL, Oliveria SA, Ellison RC. Influence of parents’ physical activity levels on activity levels of young children. J Pediatr. 1991;118(2):215–219. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuire MT, Hannan PJ, Neumark-Sztainer D, Cossrow NH, Story M. Parental correlates of physical activity in a racially/ethnically diverse adolescent sample. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(4):253–261. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderssen N, Wold B. Parental and peer influences on leisure-time physical activity in young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1992;30:253–261. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10608754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson D, Wilkes L, McDonald G. ‘If I was in my daughter’s body I’d be feeling devastated’: women’s experiences of mothering an overweight or obese child. J Child Health Care. 2007;11(1):29–39. doi: 10.1177/1367493507073059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boutelle KN, Libbey H, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Weight control strategies of overweight adolescents who successfully lost weight. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(12):2029–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 32.The partnership for a drug free America. Time to talk: the conversation starts here. 2008.

- 33.Pagnini D, King L, Booth S, Wilkenfeld R, Booth M. The weight of opinion on childhood obesity: recognizing complexity and supporting collaborative action. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2009:1–9. doi: 10.3109/17477160902763333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Booth ML, King LA, Pagnini DL, Wilkenfeld RL, Booth SL. Parents of school students on childhood overweight: the Weight of Opinion Study. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009 Apr;45(4):194–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]