Abstract

We present a case of acute traumatic optic neuropathy in 54 year old male patient. The patient presented with acute loss of vision in the right eye due to a blunt trauma to the eye. Lid haematoma and subconjunctival hemorrhage were present. Fluorescein staining was negative, anterior chamber and lens was clear. Intraocular pressure was normal. Retina and optic nerve head appeared normal on fundoscopy. The vision was “counting fingers at 1 meter” in the right eye. Color test indicated color perception dysfunction of the right eye. Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) was positive. Ocular ultrasound, orbital X ray and CT scan was normal, but visual evoked potentials test was pathologic. The consideration was made whether to treat a patient or not since there are no consensus on the treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy. We decided to treat the patient immediately with the megadoses of steroids following the protocol suggested by Cerovski. The patient responded well to the treatment and recovered vision to normal.

Key words: traumatic optic neuoophaty.

1. INTRODUCTION

Traumatic optic neuropathy (TON) is a serious vision threatening condition that can be caused by ocular or head trauma. TON is classified as direct or indirect. Direct TON usually presents as severe visual loss with minimal chances for recovery. It is caused by a penetrating injury to the area of optic nerve. Indirect TON is caused by acceleration/deceleration forces due to the blunt head or closed globe trauma. The vision loss may vary from mild to total blindness. On clinical examination retina and optic nerve head look normal. The incidence of TON after craniofacial trauma has been reported to be 2-5% (1).

The most common site of indirect TON is optic canal part of the optic nerve, followed by intracranial optic nerve and chiasm (2).

There are primary and secondary mechanisms of injury.

Primary injury is caused by mechanical shearing of optic nerve axons and contusion necrosis due to immediate ischemia from damage to the micro-circulation (3).

Secondary mechanism is apoptosis of both injured and initially uninjured adjacent neurons (4).

There are two ways of treating indirect TON. One is megadose of steroids and the other is surgical optic canal decompression.

The results of the study conducted by Levin concluded that neither corticosteroids nor optic canal surgery should be considered the standard of care for patients with traumatic optic neuropathy and that it is therefore clinically reasonable to decide to treat or not treat on an individual patient basis (5).

2. CASE PRESENTATION

We present a case of 54 year old male patient who got fist punched in the right eye by a coworker half an hour prior. He complained about the loss of vision in the right eye.

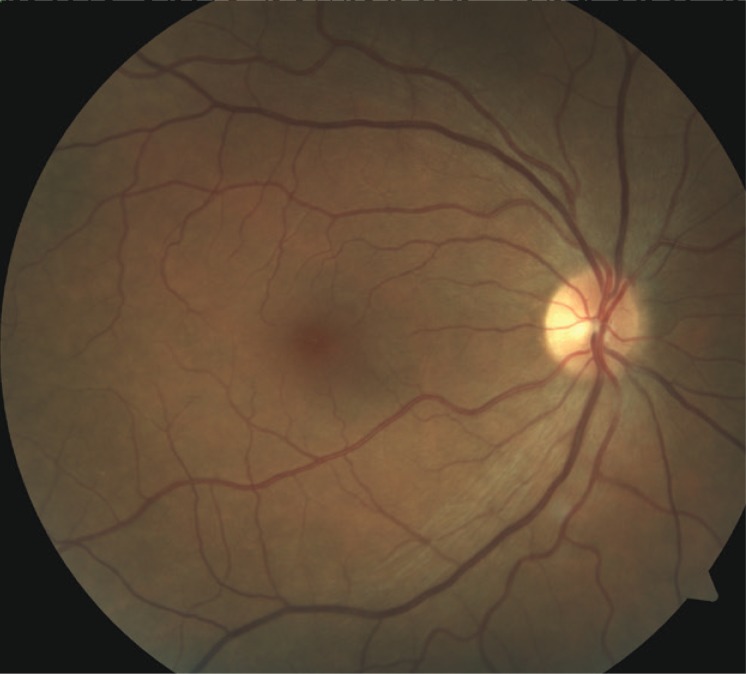

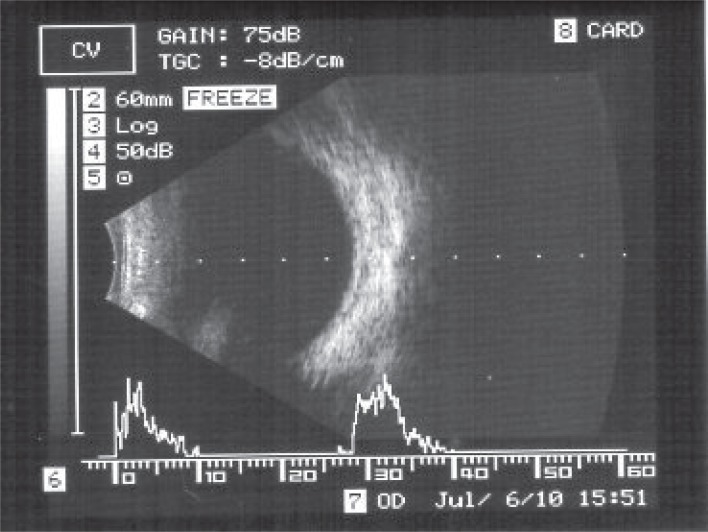

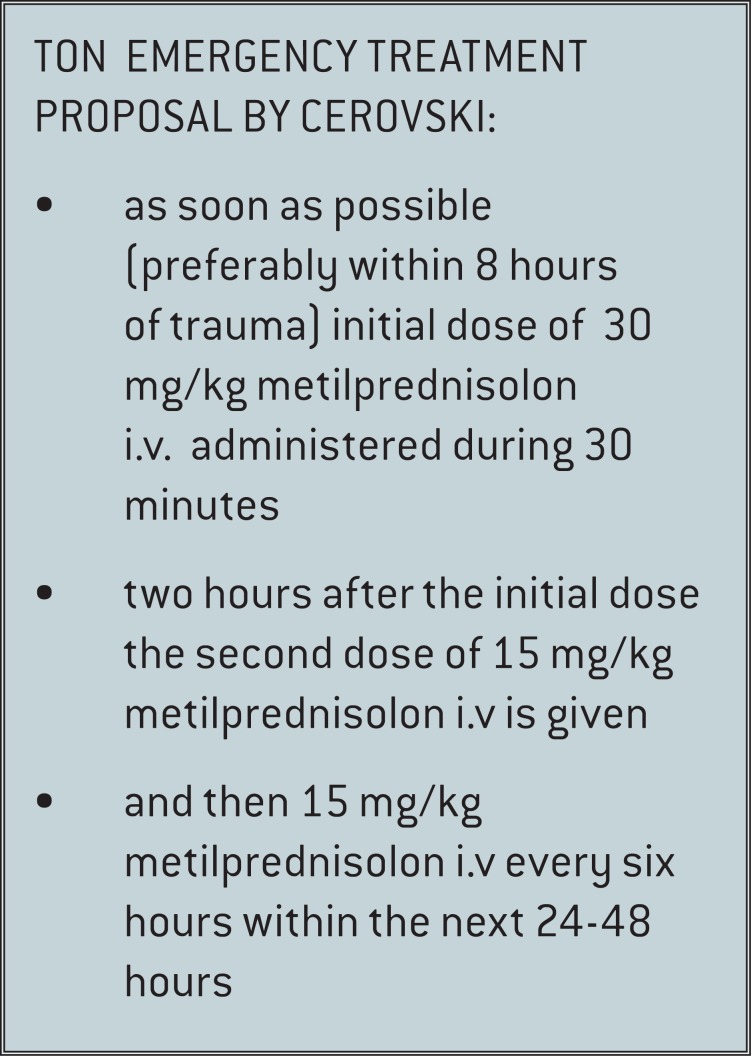

He did not loose consciousness, have dizziness, or vomiting. The patient presented with both upper and lower lid haematoma and small subconjunctival hemorrhage. Fluorescein staining was negative, anterior chamber and lens was clear. Intraocular pressure was normal. Retina and optic nerve head appeared normal on fundoscopy (Figure 1). The vision was “counting fingers at 1 meter” in the right eye and 0.5 without the correction in the left eye on the Snellen chart. “Mydriacyl bottle cap or Red desat” subjective test indicated color perception dysfunction of the right eye (Figure 2). Relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) was positive, but mild in the right eye. We immediately performed ocular ultrasound which was normal (Figure 3) and orbital X ray which showed no signs of bone fracture. We decided to treat the patient immediately with the megadoses of steroids following the protocol suggested by Cerovski (6) (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Normal fundus.

Figure 2.

Mydriacyl bottle cap or Red desat subjective test: a) left eye perception; b) right eye (TON) perception.

Figure 3.

Ultrasound of the right eye.

Figure 4.

TETP by Cerovski.

The first dose was methylprednisolone in intravenous doses of 30 mg/kg, followed 2 hours later by a dose of 15 mg/kg, and 3 additional doses after every 6 hours of 15 mg/kg of methylprednisolone i.v. Patient also received steroid eyedrops 4 times a day. The following day patients vision began to improve, BCVA (best corrected visual acuity) being 0.3 in the right eye. And the 3 rd day BCVA was 0.5. On the forth day it improved to 0.7, stenopeic 1.0. On the second day VEP (visual evoked potentials) test was performed and it showed P100 wave of lower amplitudes and latency delay in the right eye, and was normal in the left eye. CT orbital scan was also done on the second day and it did not show any pathology (Figure 5). Patient came for a follow up visit after seven days and the vision was normal.

Figure 5.

CT scan of orbits and eyes.

3. DISCUSSION

The treatment of TON is a somewhat controversial. There is not any specific guidance how to treat and weather to treat at all. The International Optic Nerve Trauma Study was organized to help clarify the value of different treatments of TON. Within 7 days of injury, one group of patients were untreated, second group was treated with corticosteroids, and the third was treated with optic canal decompression surgery. There were no significant differences between any of the treatment groups. The conclusion of the study was that neither corticosteroids nor optic canal surgery should be considered the standard of care for patients with TON. And that every ophthalmologist should decide to treat or not treat on an individual case (5). The other study by Chou et al included 58 patients: 10 patients were untreated, 23 were treated with corticosteroids, and 25 patients were treated with optic canal decompression and corticosteroids (7). The results of visual improvement were 0% in the untreated group, 57% in the treated with steroids group, and 60% in the group treated both surgically and with steroids. The study concluded that the patients in the treated groups did statistically better than the untreated patients.

4. CONCLUSION

Immediately after the patient was admitted to the hospital we started the treatment with the mega doses of steroids. We decided to treat the patient because of the several reasons. One was that he presented within the first hour of the time of injury and as Cerovski suggested the treatment should start preferably within the first 8 hours. Second reason was that he was otherwise healthy individual. And the third was that patients are usually scared and psychologically traumatized and expect some sort of treatment especially when the vision loss is severe. Since there are no definite recommendations other than to treat on the individual basis, you can tell the patient “we can do nothing and hope that the vision will improve”, or “we can do something and also hope that the vision will improve”. Most of the people are inclined toward the second option. Our patient responded the same way and was very cooperative and satisfied with the treatment during the hospitalization.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Al-Qurainy A, Stassen LFA, Dutton GN, et al. The characteristics of midfacial fractures and the association with ocular injury: a prospective study. Brit J Oral Maxillofacial Sur. 1991;29:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90114-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crompton MR. Visual lesions in closed head injury. Brain. 1970;93:785–792. doi: 10.1093/brain/93.4.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh FB, Hoyt WF. Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. 3rd. Vol. 3. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1969. p. 2380. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vorwerk CK, Zurakowski D, McDermott LM, et al. Effects of axonal injury on ganglion cell survival and glutamate homeostasis. Brain Res Bull. 2004;62:485–490. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(03)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin LA, Beck RW, Joseph MP, et al. The treatment of traumatic optic neuropathy: the International Optic Nerve Trauma Study. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:1268–1277. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00707-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerovski B. Neurooftalmološke manifestacije kraniocervikalne ozljede. In: U: Šikic J, Cerovski B, editors. ur. Okuloorbitalna ozljeda i neurooftalmološke manifestacije kraniocervikalne ozljede. Zagre: Medicinska naklada; 2004. pp. 23–31. 41-48. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou PI, Sadun AA, Chen YC, et al. Clinical experiences in the management of traumatic optic neuropathy. Neuro-ophthalmology. 1996;16:325–336. [Google Scholar]