Abstract

Consistent left-right asymmetry in organ morphogenesis is a fascinating aspect of bilaterian development. Although embryonic patterning of asymmetric viscera, heart, and brain is beginning to be understood, less is known about possible subtle asymmetries present in anatomically identical paired structures. We investigated two important developmental events: physiological controls of eye development and specification of neural crest derivatives, in Xenopus laevis embryos. We found that the striking hyperpolarization of transmembrane potential (V mem) demarcating eye induction usually occurs in the right eye field first. This asymmetry is randomized by perturbing visceral left-right patterning, suggesting that eye asymmetry is linked to mechanisms establishing primary laterality. Bilateral misexpression of a depolarizing channel mRNA affects primarily the right eye, revealing an additional functional asymmetry in the control of eye patterning by V mem. The ATP-sensitive K+ channel subunit transcript, SUR1, is asymmetrically expressed in the eye primordia, thus being a good candidate for the observed physiological asymmetries. Such subtle asymmetries are not only seen in the eye: consistent asymmetry was also observed in the migration of differentiated melanocytes on the left and right sides. These data suggest that even anatomically symmetrical structures may possess subtle but consistent laterality and interact with other developmental left-right patterning pathways.

1. Introduction

Consistent (directionally biased) left-right asymmetry of viscera, heart, and brain is overlaid upon the overall bilaterally symmetric body plan of a wide range of organisms [1, 2]. Errors in this process form an important class of human birth defects [3–5]. Thus, understanding left-right patterning and the interaction of individual organ systems with the axial polarity of the body is of great interest for both basic evolutionary developmental biology and for the biomedicine of birth defects. Likewise, the highly lateralized functions of the brain (e.g., language, speech, and handedness) and their partial disconnect from anatomical left-right asymmetry have been a fascinating topic under study for several decades [6, 7].

Recent studies have identified numerous genetic [8–13], biophysical [14–16], and physiological [17–21] mechanisms that underlie large-scale left-right asymmetry and the situs of asymmetric organs. However, much less well-understood are subtle asymmetries occurring in paired body structures which are anatomically symmetrical [14].

Such asymmetries manifest in several ways. First, quantitative morphometrics of paired structures can reveal cryptic polarity that may not be apparent from gross morphological examination [22]; insect wings are a good example of this phenomenon [23, 24], as are human foot size [25] and sex organ placement [26]. It is crucial to note that such biased examples of left-right patterning (where the asymmetry is coordinated in a consistent fashion with the other two major axes) are a distinct phenomenon from fluctuating asymmetry, which involves simple differences between the left and right sides derived from developmental noise [27, 28].

Second, differences of gene expression have been described in seemingly symmetric body structures. These include consistent differences in the timing of highly dynamic bilateral transcriptional waves that drive the segmentation clock of somitogenesis [29–31], as well as long-term asymmetries in expression of markers such as EGF-like growth factors and MLC3F [32, 33].

Perhaps the most interesting types of subtle asymmetries are those that are revealed only under functional perturbation. It has long been known that consistently sided unilateral limb defects are induced in rodents by some compounds such as cadmium [34–36]. Spontaneous genetic defects sometimes uncover biased asymmetries, as seen in several human syndromes that unilaterally affect the limbs [37], face [38], or hips [39]. Holt-Oram syndrome (Tbx5 related) presents upper limb malformations which are much more common on the left side [37, 40–42], while fibular hypoplasia affects the right side more often [43]. Indeed, a variety of human syndromes affecting paired organs have a significant bias for one side [39]. Curiously, unilateral defects in otherwise symmetrically placed structures (e.g., teeth) in monozygotic twins exhibit a mirroring-opposite sidedness in the two twins (reviewed in [44]). Hemihyperplasia [45, 46], a rare phenomenon where one side of the body abnormally overgrows, is right biased [47]. Importantly, targeted molecular-genetic experiments in tractable model systems are beginning to reveal entry points into this process; for example, attenuated FGF8 signaling results in consistently biased left-right asymmetric development of the pharyngeal arches and craniofacial skeleton in zebrafish [48].

Most studies of asymmetry use cardiac and visceral situs as readout, focusing on mechanisms that determine the laterality of major body organs. However, the consistent asymmetries revealed in the above examples hint at the possibility that left-right identity (resulting from tissues' interactions with the pathways that establish the left-right axis) could be far more prevalent throughout the body than is currently appreciated. What signaling pathways might underlie laterality information in anatomically symmetrical tissues? While most work on morphogenetic controls focuses on biochemical pathways [49, 50] and physical forces [51, 52], exciting recent as well as classical data demonstrate the importance of endogenous bioelectrical determinants of cell behavior and large-scale patterning [53–59]. We thus focused our search on asymmetries that manifest at the level of functional physiology.

Prior work in the planarian flatworm model system revealed that during head regeneration, the right eye was significantly more sensitive to inhibition of the H, K-ATPase ion pump than the left, in terms of frequency of induced patterning defects [60]. In our efforts to understand the functions of spatial gradients in transmembrane potential (V mem) during vertebrate development and regeneration [18, 61–65], we examined eye development in embryos of Xenopus laevis. Using a noninvasive assay with a fluorescent reporter of V mem [66, 67], it was found that the nascent eye fields are demarcated by a localized hyperpolarization of V mem [68, 69]; strikingly, this physiological signature of eye fate is consistently biased, with cells on the right side of the midline hyperpolarizing first. We also report similar consistent subtle asymmetries in the migratory behavior of neural crest-derived melanocytes. Here, we molecularly characterize this novel asymmetry, revealing that physiological analysis can uncover cryptic differences in patterning information not apparent from molecular marker analysis or anatomical examination. Understanding such subtle functional asymmetries may become useful in addressing and targeting diseases with asymmetric manifestations.

2. Results

2.1. Eye Field Cells Exhibit a Consistently Asymmetric V mem

V mem plays a crucial functional role in defining the eye fields during the development of the Xenopus embryo [68, 70]. Using the fluorescent voltage-sensitive reporter dye CC2-DMPE [71] in vivo to characterize real-time changes in membrane potential [17, 65, 72], we discovered a novel physiological asymmetry between the left and right eye primordia. At stage 18, normal Xenopus embryos exhibit bilateral clusters of cells with a more strongly polarized V mem than their neighbors around the putative eye region (Figure 1(a), red arrowheads [68]). Surprisingly, real-time imaging analysis revealed that the right eye field is polarized first, followed by polarization of the left eye field (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Though not absolute, this physiological asymmetry is consistently biased, since more than 3-fold as many embryos polarized first on the right compared to those that began polarization on the left (Figure 1(b); N = 44, P < 0.001, Chi-squared test comparison with an unbiased expectation). In addition to the significant asymmetry at one key timepoint, we followed 6 individual embryos (imaged through eye development stages) to estimate the temporal difference between hyperpolarization events on the two sides. At 20°C, 4 embryos exhibited a 30 min delay in the hyperpolarization of the left eye spot, while 2 embryos exhibited a 20 min delay in the appearance of the left eye spot hyperpolarization. We conclude that eye development in Xenopus is inherently asymmetric, with the right eye field most often initiating the endogenous program of polarization.

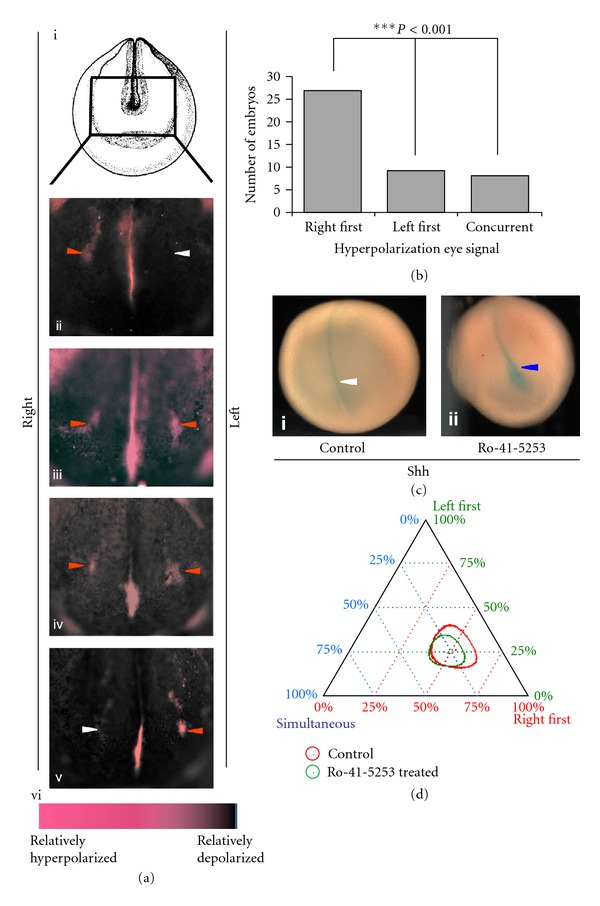

Figure 1.

Rightward bias in induction of polarization signal regulating eye development. (a) Incubation in voltage-sensitive CC2-DMPE dye of multiple Xenopus embryos tracked from stage 18 to stage 20 shows the representative temporal progression of hyperpolarization signal (red arrowheads) during development (ii)–(v). White arrowheads indicate the lack of a coherent (contiguous) spot of signal. (vi) Color bar representing the scale of relative depolarization and hyperpolarization as seen with the CC2-DMPE dye. (b) Bar graph comparing a group of Xenopus embryos (n = 44) that were tracked individually and analyzed for the first detectable hyperpolarization signal using CC2-DMPE; a significant bias is observed favoring the right side. A pairwise comparison and Chi-squared test analysis were done between the groups. (c) In situ hybridization analysis of Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signal in stage 18 Xenopus embryos either untreated (control) ((i) white arrowhead) or treated with 1.5 μM retinoic acid receptor inhibitor Ro-41-5253 ((ii) blue arrowhead) from midgastrula stage. Ro-41-5253 treatment significantly enhances the Shh expression signal in 92% of treated embryos (n = 29). (d) Categorical data analysis using a ternary plot shows that the treatment with Ro-41-5253 (1.5 μM) that inhibits retinoic acid receptor signal resulted in no significant change in the rightward bias of polarization signal (as observed via CC2-DMPE staining) involved in Xenopus eye development. In control (untreated) embryos the polarization was 51.5% right first, 26.5% left first, and 22% simultaneous (n = 72). In the Ro-41-5253-treated embryos the polarization was 48% right first, 25% left first, and 27% simultaneous (n = 126). The circles in the plot represent 95% confidence intervals. Using the calculations provided by a ternary plot algorithm (https://webscript.princeton.edu/~rburdine/stat/three_categories), the results are statistically significant only when there is no overlap of the confidence intervals.

Previous studies in chick and mouse embryos have shown that somites, though anatomically symmetrical, also exhibit an underlying asymmetry [30, 73]. Somites are shielded from this inherent asymmetry by the action of retinoic acid (RA) signaling, resulting in symmetrical development. In order to determine whether the asymmetry in eye signals is due to an incomplete shielding effect of RA-dependent signaling, we treated embryos with 1.5 μM of the broad-spectrum RA receptor inhibitor Ro-415253. Ro-41-5253 at this concentration has previously been shown to affect RA signaling in Xenopus [74]. We used a previously documented midline marker—Sonic Hedgehog (Shh), to further confirm the effect of Ro-41-5253. Xenopus embryos were left untreated (Controls) or treated with Ro-41-5253 (1.5 μM), and the Shh expression was evaluated at stage 18 by in situ hybridization (Figure 1(c)). Control embryos showed Shh expression as a thin line along the dorsal midline (Figure 1(c), (i) white arrowhead). However, Ro-41-5253-treated embryos (>90%) showed a clear increase in Shh expression along the midline (Figure 1(c), (ii) blue arrowhead) as previously documented [74]. This change in Shh expression confirms that at 1.5 μM Ro-41-5253 is effective in inhibiting RA receptor signaling.

The effect of Ro-41-5253 on the asymmetric eye polarization signal was analyzed in stage 18 embryos using the CC2-DMPE voltage reporter dye. Each treatment (control and Ro-41-5253) was plotted on a ternary graph using three measures of eye-related polarization signal (right first, left first, and simultaneous) according to the methods described previously [75] (Figure 1(d)). The circles in the plot represent respective error regions of 95% confidence intervals. Using the calculations provided by a ternary plot algorithm (https://webscript.princeton.edu/~rburdine/stat/three_categories), the results are considered statistically significant (P < 0.05) when there is no overlap of the 95% confidence intervals. Analysis of the polarization signal in the Ro-41-5253-treated embryos at stage 18 showed a significant right side first bias (n = 126) (right first 48%, left first 25%, and simultaneous 27%) (Figure 1(d), green circle), similar to that of control/untreated embryos (n = 72) (right first 51.5%, left first 26.5%, and simultaneous 22%) (Figure 1(d), red circle; P > 0.05, ternary plot algorithm). Thus, RA signaling does not play a role in the right-side-first bias of V mem signal in the eye primordia.

2.2. Eye Field V mem Asymmetry Is Perturbed by Disruption of pH-Mediated Left-Right Patterning

We next asked whether eye asymmetry is controlled by the same pathway that governs left-right patterning of the heart and viscera. We used low-pH treatment at cleavage stages to specifically induce randomization of asymmetric gene expression and subsequent organ situs; this is known to interfere with the earliest steps of left-right patterning by inhibiting the proton efflux of the plasma-membrane H+ V-ATPase which is required for normal laterality [17]. The very early timing of this treatment ensured that it could not affect eye development directly but rather allowed us to ask whether randomization of the body's main left-right patterning pathway likewise randomized the observed physiological eye asymmetry. The efficacy of our loss-of-function treatment upon normal left-right asymmetry was confirmed by scoring the tadpoles at stage 45 for altered sidedness of the heart, gut, or gallbladder. Normal tadpoles (untreated, Figure 2(a) (i)) have a right-ward looping heart (red arrow), a left-sided gut coil (yellow arrow), and a right-sided gallbladder (green arrow). In contrast, treated tadpoles (Figure 2(a), (ii)-(iii)) showed randomization of the positions of the heart, gut, and gallbladder (independent assortment of organs), as described previously [76, 77], in the absence of generalized toxicity or other malformations (including any dorsoanterior defects). Heterotaxia was induced in 19% of embryos (Figure 2(b)) (the degree of the pH perturbation was kept well below extreme values to be compatible with continued development, to avoid dorsoanterior malformations that might confound analysis of eye development, resulting in a submaximal randomization penetrance). Each treatment (control and pH) was plotted on a ternary graph as described above; the results are considered statistically significant (P < 0.05, ternary plot algorithm) when there is no overlap of the 95% confidence intervals. Analysis of the polarization signal in the siblings of treated embryos at stage 18 showed that the rightward bias seen in the normal embryos (n = 191) (right first 51%, left first 23%, and simultaneous 26%) (Figure 2(c)) was significantly randomized in treated embryos (n = 105, P < 0.05, ternary plot algorithm) (right first 31%, left first 39%, and simultaneous 30%) (Figure 2(c)). We conclude that the determination of eye field voltage asymmetry is downstream of early ion flow dynamics, as is the positioning of the heart and viscera [8, 78].

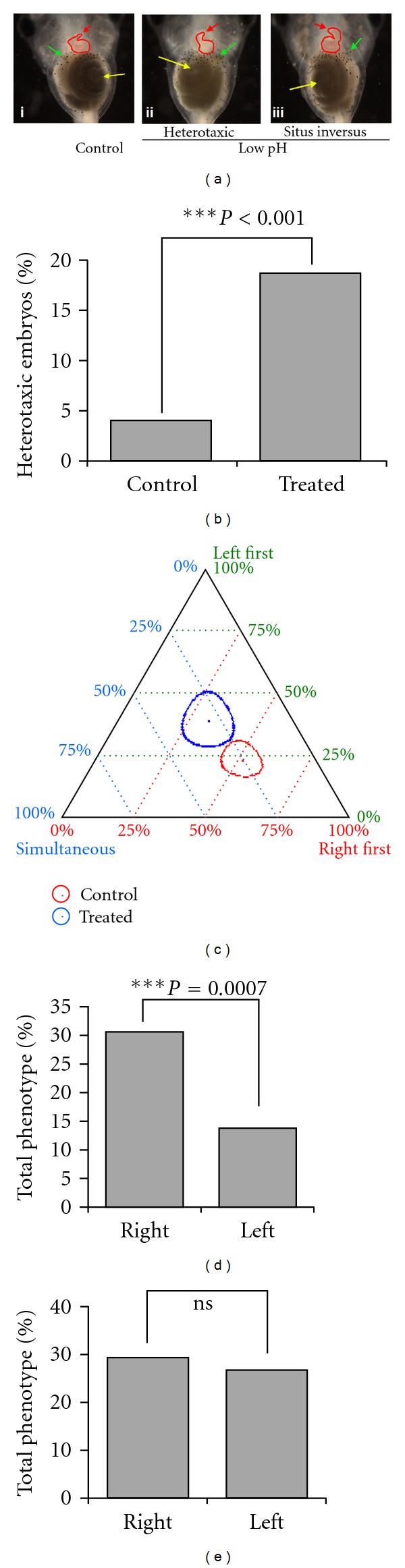

Figure 2.

Right-ward bias in eye development is linked to the body left-right axis. (a) (i) Brightfield images of tadpoles at stage 45 showing normal positioning of the organs (situs solitus); rightward looping heart (red arrow), leftward coiling of gut (yellow arrow), and right side placement of gallbladder (green arrow) along the left-right axis in untreated controls. (ii)-(iii) Brightfield images of tadpoles at stage 45 after incubation in pH 4.00 0.1XMMR. (ii) Showing heterotaxic positioning of organs; rightward looping heart (red arrow) rightward coiling of gut (yellow arrow), and left side placement of gallbladder (green arrow). (iii) Showing inverse positioning of the organs (situs inversus); leftward looping heart (red arrow), rightward coiling of gut (yellow arrow), and left side placement of gallbladder (green arrow) along the left-right axis in tadpoles. (b) Bar graph showing percentage of embryos with heterotaxia upon incubation in 0.1XMMR (pH 4) (n = 481) in comparison to untreated controls (n = 419). The controls and treated groups were analyzed using Chi-squared test. (c) Categorical data analysis using a ternary plot shows that treatment with pH = 4 0.1XMMR that induced left-right body axis randomization also resulted in randomization and loss of the rightward bias of the polarization signal (observed via CC2-DMPE staining) involved in Xenopus eye development. In control embryos the polarization bias was 51% right first, 23% left first, and 26% simultaneous. The pH = 4 0.1XMMR-incubated embryos showed randomization of polarization signal 31% right first, 39% left first, and 30% simultaneous. The circles in the plot represent 95% confidence intervals. Using the calculations provided by a ternary plot algorithm (https://webscript.princeton.edu/~rburdine/stat/three_categories), the results are statistically significant (P < 0.05) when there is no overlap of the confidence intervals. (d) Bar graph showing right-ward bias in malformed eye upon perturbation of polarization signal. Embryos were injected with GlyR in the dorsal two cells (eye precursor cells) at the 4-cell stage and treated with IVM to induce depolarization in injected cells. Percentages of phenotypic embryos with a single malformed eye are depicted (n = 763). Data was analyzed using a Chi-square test comparing the right and left groups. (e) Bar graph showing no left-right bias in malformed eye upon perturbation of Pax6. Embryos were injected with DNPax6 in the dorsal two cells (eye precursor cells) at 4-cell stage. Percentages of phenotypic embryos with a single malformed eye are depicted. Data was analyzed using a Chi-squared test (n = 294).

2.3. Eye Fields Are Asymmetrically Sensitive to Perturbation of V mem

To determine whether functional asymmetries (differential sensitivity to perturbation of voltage levels, as previously observed in planaria by [60]) are present in the eye field in addition to the asymmetric endogenous sequence of polarization, we experimentally depolarized the cells' V mem using a carefully titered strategy that allowed us to manipulate V mem and affect subtle bioelectrically controlled processes without inducing generalized toxicity or massive malformation [68]. We capitalized upon the glycine-gated chloride channel [79], which can be opened by exposure to the compound Ivermectin (IVM) [80]—a convenient method of controlling cellular potential that we have previously used to probe the role of V mem in eye induction and metastatic-like transformation [62, 68]. Under normal conditions and standard 0.1X MMR external medium supplemented with Ivermectin, misexpression of these channels depolarizes cells (since the negatively charged chloride ion leaves GlyR-expressing cells down its concentration gradient [62]). We recently showed that injection of GlyR mRNA indeed alters the polarization pattern observed in the putative eye region and affects eye patterning [68].

Because the eyes are derived from the dorsal blastomeres at the 4-cell stage [88], we injected GlyR mRNA into the 2 dorsal cells and developed the embryos to stage 42. On average 45% of the affected embryos showed defects in only one eye; interestingly, there was a significant bias (2.5-fold) towards defects in the patterning of the right eye (Figure 2(d); P = 0.0007, Chi-squared test). As a control, we injected in a similar manner a dominant-negative Pax6 (DNPax6) mRNA which had been previously shown to disrupt Xenopus eye development [68, 89]. No statistically significant bias toward right (30%) or left (27%) eye malformation was observed among animals with only 1 eye affected (total 57% with one eye defect) (P > 0.05; n = 294 Chi-squared test in comparison with an unbiased expectation; Figure 2(e)), suggesting that the Pax6 signal during eye patterning is left-right neutral.

From these results, we conclude that morphogenesis of the right eye is more sensitive to perturbation of V mem than is that of the left.

2.4. K ATP Channel Probes Reveal Asymmetric Expression in the Eye Tissues of Developing Embryos

We next sought to determine the molecular basis for the observed asymmetry in transmembrane potential of the eye fields. Asymmetries in V mem with significant consequences for cell behavior are often driven by differential expression of ion channels [90–92]. KATP channels [93] are octamers formed from 4 proteins from the inward-rectifying potassium family Kir6.x (either Kir6.1 or Kir6.2) associated with 4 sulphonylurea receptors (SUR1 and SUR2). We had previously found that altering the bioelectric state with dominant negative Kir constructs that target endogenous KATP channels result in the formation of ectopic eyes [68]. Hence, we analyzed the expression pattern of KATP channel subunits in Xenopus embryos [94] by in situ hybridization at stage 18 and stage 30. Previously characterized KATP channel genes [87, 95] showed no asymmetric expression in the relevant tissues; however, probes made against the murine KATP genes revealed a striking set of expression patterns.

Probes for all four KATP channel subunits revealed signal mainly in the head, including the putative eye regions at stage 18 (Figure 3(a), (i)–(iv) blue arrowheads) and intensely stained the developing eye at stage 30 (Figure 3(a), (v)–(viii) blue arrowheads). Stage 30 embryos also showed expression in the neural tube (Figure 3(a), (v), (viii)). Stage 30 embryos were sectioned as illustrated in Figure 3(b). Probes to Kir6.2, SUR1, and SUR2 showed signal in the inner layer of the epidermis with intense expression in the lens placode (Figure 3(b), (ii)–(iv) blue arrowheads). Kir6.1 expression was found in the retinal layer of the developing eye (Figure 3(b), (i) blue arrowheads). Kir6.1 was also found in the cells surrounding the eye tissue and along the brain ventricle (Figure 3(b), (i)). Strikingly, expression of the SUR1 transcript was asymmetric, being expressed strongly in the right eye (Figure 3(b), (iii)-(iv), n = 8). No-probe controls and SUR1 and 2 sense probes, exposed for the same length of time as embryos probed with antisense RNA, exhibited no signal at any stage tested (Figure 3(c), (i), (ii)). These data reveal a novel left-right asymmetric marker distinguishing the left and right eyes at the transcriptional level. In our previous study we implicated the KATP channel in regulating the eye-specific polarization signal [68]. Although the native Xenopus transcripts matching the expression of these probes remain to be identified within the incompletely sequenced X. laevis genome, the current findings of asymmetry revealed by mouse KATP channel probes are consistent with endogenous KATP channels as a basis for the physiological differences between the left and right eyes.

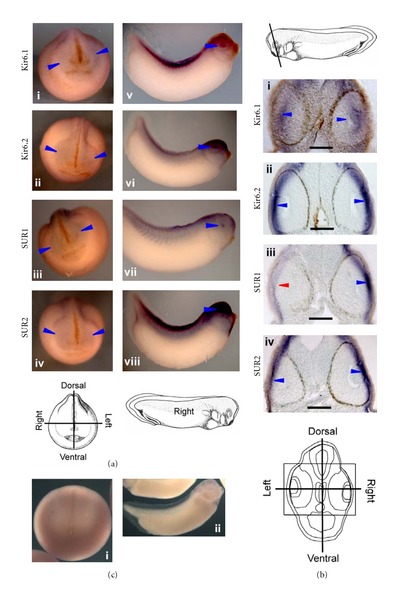

Figure 3.

KATP channels are expressed in the putative eye regions and in the eye tissue in a left-right asymmetric manner. (a) Xenopus embryos at stage 18 (i)–(iv) and stage 30 (v)–(viii) were analyzed by in situ hybridization for KATP channel subunits showing their presence in the putative eye region ((i)–(iv) blue arrowheads) as well as in differentiated eye tissue ((v)–(viii) blue arrowheads). All four subunits (Kir6.1, Kir6.2, SUR1, and SUR2) were found to be present in the putative and developed eye tissue. In addition to the eye tissue, the KATP channel subunits were also present in the general head region and the dorsal region of the trunk. Illustration shows a stage 18 embryo with the dorsal-ventral and the left-right axes. (b) Transverse JB4 sections of in situ hybridized Xenopus embryos at stage 30 (i)–(iv) showing left-right distribution of the KATP channel subunits. Illustration shows the plane of sectioning of the stage 30 embryo. Kir6.1 expression is found in the inner retinal part of the eye vesicle ((i) blue arrowheads) and in the brain especially in the cells lining the ventricle and in some cells surrounding the eye tissue. Kir6.2, SUR1, and SUR2 expression is found in the inner layer of the 2-layer epidermis with intense staining at the lens placode ((ii)–(iv) blue arrowheads). Kir6.1, Kir6.2, and SUR2 expression is symmetric ((i), (ii), and (iv) blue arrowheads). SUR1 shows asymmetric distribution ((iii) red and blue arrowheads) where red arrowheads indicate the side with lessened expression. Scale bars = 100 μm. Schematic shows a transverse section of a stage 30 embryo with the dorsal-ventral and the left-right axes indicated. (c) Sense probes showed no signal detected at neurula (i) or tailbud (ii) stages.

2.5. Melanocyte Colonization of Lateral Trunk Is Consistently Left-Right Asymmetric

The discovery of a cryptic functional and physiological asymmetry in a paired organ led us to examine other processes for asymmetries that may have heretofore escaped notice; we were especially interested in other descendants of neural precursors. Pigment cells (melanocytes, derived from neural crest cells) were identified using in situ hybridization with a probe against Trp2 (also known as Dct), a definitive marker of melanocytes [96] at stage 30. We observed that 79% of embryos had significantly more Trp2-positive cells (melanocytes) on their left side compared to their right side (Figures 4(a) and 4(b) and Table 1 (n = 28 and P = 0.002, paired t-test)).

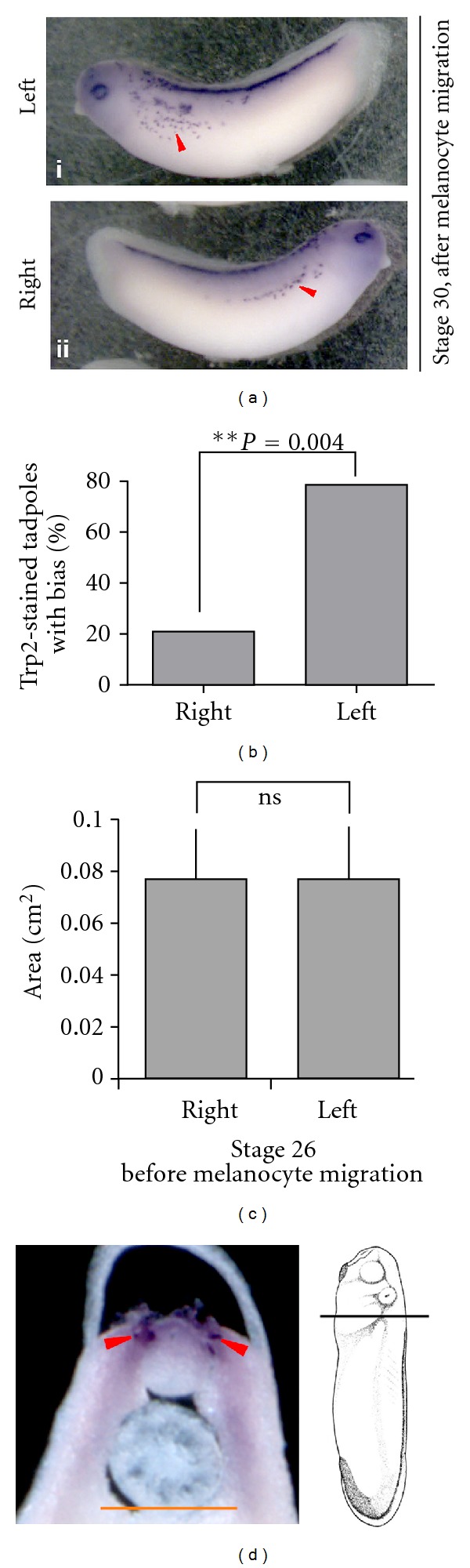

Figure 4.

Biased migration of melanocytes along the left-right axis. (a) Xenopus embryos at stage 30 analyzed by in situ hybridization for melanocyte marker trp2 show a higher number of melanocytes on the left side (i) as compared to the right side (ii) of the embryo. Red arrowheads indicate the melanocytes being counted. (b) Quantification of a number of stage 30 embryos showing biased trp2 spots indicates that 78.6% of embryos show a leftward bias of trp2 staining. 21.4% of embryos showed higher trp2 staining on the right side. The data were analyzed using a two-tailed Binomial calculation; n = 28. (See Table 1 for details). (c) Quantification of Xenopus embryos at stage 26 analyzed by in situ hybridization for trp2 shows no asymmetry in melanocyte number prior to their migration. Due to dense staining at this early stage individual stained cells could not be resolved and counted, hence the stained region was marked, and the area was quantified. Quantification of the trp2 stain on the left and right sides of embryos (n = 10) shows no significant difference in the staining. The areas of the signal on right and left sides were compared using a t-test. (d) Transverse agarose sections of in situ hybridized Xenopus embryo at stage 26 showing left-right distribution of the melanocyte marker trp2 as measured. Illustration shows the plane of sectioning of the stage 26 embryo. Symmetric trp2 expression (red arrowheads) is found in the area around the neural tube. Scale bar = 200 μ.

Table 1.

Biased migration of melanocytes. Embryos were stained with the melanocyte marker Trp2 using in situ hybridization to identify pigment cells. The pigment spots on both the left and the right side of each embryo were counted. Student's t-test analysis of the raw data shows a significantly higher (P = 0.002) melanocyte migration on the left side of the embryos.

| Embryo | Left | Right |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 16 |

| 2 | 10 | 9 |

| 3 | 18 | 27 |

| 4 | 11 | 13 |

| 5 | 7 | 4 |

| 6 | 15 | 17 |

| 7 | 29 | 24 |

| 8 | 19 | 13 |

| 9 | 15 | 10 |

| 10 | 1 | 2 |

| 11 | 27 | 18 |

| 12 | 10 | 6 |

| 13 | 8 | 3 |

| 14 | 7 | 3 |

| 15 | 45 | 25 |

| 16 | 7 | 4 |

| 17 | 11 | 10 |

| 18 | 9 | 14 |

| 19 | 7 | 5 |

| 20 | 10 | 4 |

| 21 | 6 | 4 |

| 22 | 12 | 7 |

| 23 | 6 | 7 |

| 24 | 16 | 8 |

| 25 | 15 | 5 |

| 26 | 7 | 5 |

| 27 | 10 | 7 |

| 28 | 7 | 4 |

|

| ||

| Average | 13.21 | 9.78 |

|

| ||

| Stddev | 9.11 | 7.08 |

|

| ||

| t-test (paired) | 0.002088 | |

|

| ||

| Embryos with more melanocytes | 22 (78%) | 6 (22%) |

This bias in melanocyte numbers could be a result of left-right-biased differentiation of neural crest cells into melanocytes or due to biased migration of differentiated melanocytes. To test whether the observed asymmetry in melanocytes was due to asymmetric melanocyte differentiation before migration (greater number of melanocytes being produced on one side at the very beginning of melanocyte specification), we performed in situ hybridization with Trp2 at an earlier stage 26 (before melanocyte migration begins). At this stage, in sections taken through the trunk, quantitative analysis of the area of Trp2-positive regions showed no significant difference between the right and left sides (n = 10) (Figure 4(c)). These results show that the left-side bias seen in melanocyte numbers at stage 30 is likely not due to biased differentiation of melanocytes from neural crest cells and favors a mechanism based on biased migration rates of differentiated melanocytes. From these results we also conclude that subtle left-right asymmetry in symmetric structures is not unique to the eye but also extends to the behavior of migratory neural crest derivatives (Figure 5).

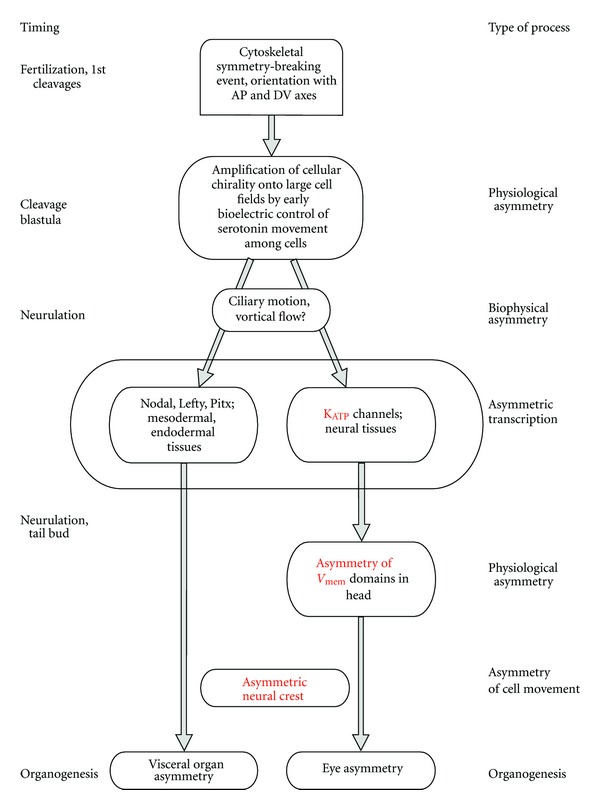

Figure 5.

A model of physiological asymmetries within the overall scheme of the left-right patterning pathway. In Xenopus, bilateral symmetry is first broken, and the left-right axis is consistently oriented with respect to the dorsoventral and anterior-posterior axes, during early cleavage stages [8, 81]. The intracellular chirality is amplified onto multicellular cell fields during cleavage and blastula stages by the voltage-dependent movement of small molecule determinants through gap junctions [82–84]. The transduction of voltage gradient differences by epigenetic mechanisms [85] and other biophysical events such as ciliary movement [86] initiates at least two asymmetric transcriptional cascades. The first is the well-known Nodal, Lefty, and Pitx2 cassette that drives asymmetric organogenesis of the visceral organs. The other is the asymmetry of KATP channel subunits expressed in neural tissues, which results in asymmetric gradients of resting potential that directs development of the eye [87]. Future work will determine the functional linkage of the reported asymmetry in neural crest cell movement.

3. Discussion

3.1. Development of Xenopus Eyes Is Asymmetric

Previously, we showed that a specific range of relatively hyperpolarized membrane voltage regulates Xenopus eye development [68, 69]. While the eyes are paired organs and have been assumed to be symmetric, here we show that the bioelectric signal that endogenously regulates their formation exhibits a distinct and consistent left-right asymmetry. Hyperpolarization of the right eye occurs first (Figure 1), and the right side is consistently more sensitive to functional perturbations (Figures 2(d) and 2(e)). This observation of a right-side-first bioelectrical signal coincides with previous documentation of a morphological right-sided asymmetry of neural structures in Xenopus, including retina, olfactory placode, and ganglia of nerve viii [97] and is consistent with developmental asymmetries of the visual system described in flatfish [98], Ciona intestinalis [99], and chicken [100–102].

While consistent and statistically significant, the degree of this asymmetry (61%) is not as high as that of crucial visceral organs like heart and gut (99% in wild-type Xenopus). Other groups have suggested that developmental asymmetries observed in symmetric structures arise as a side effect from incomplete shielding of symmetrical structures from the left-right signaling pathway coincident in time and space and have demonstrated that retinoic acid signaling has a role in protecting developing symmetric structures from these left-right signals. Since blocking retinoic acid signaling does not exacerbate the level of asymmetry in the eye signal in our studies (Figure 1(d)), our data do not support the role of retinoic acid in the shielding of this asymmetry. However, it is possible that another (yet unknown) pathway exists that serves to reduce or mask an inherent asymmetry of the eye formation process, derived from the influence of body-wide left-right patterning signals. Another intriguing possibility is that this asymmetry is not a side effect but instead has been evolutionarily conserved due to functional relevance.

Consistent asymmetry in handedness is seen in 60% of nonhuman primates but in 90% of humans [6, 103]. Moreover, a number of studies have reported left-right asymmetries in visual function related to food/prey and predatory responses in fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals [104–110]. It is possible that subtle differences in the bioelectrical patterning signals of the visual system, along with asymmetries of brain and cognitive processing, are involved in establishing these behavioral and functional asymmetries. In C. elegans, for example, a stochastic lateral inhibition system involving ion channels results in lateralized neural differentiation and function [111–115]. It is tempting to speculate that this asymmetric bioelectric signal could trigger differential genetic, chemical, and/or biophysical patterns that overlay upon the universal eye development pattern allowing the left and right sides of the visual system to develop differing visual functionality. This is supported by our observation that depolarization-mediated disruption of endogenous bilateral polarization cues results in a right-biased disruption of eye formation. However, further functional studies will be required to test this hypothesis. In addition, this mechanism appears to be conserved, as a similar right-biased disruption of eye regeneration is observed in planaria upon depolarization [60]. Thus, comparative studies of possible asymmetries of developmental physiology and subsequent function of eyes (and other structures) among taxa may pay off in the discovery of novel asymmetries in paired organs.

3.2. Eye Asymmetry versus Body Asymmetry

In the past few years, the zebrafish has become a good model for studies of asymmetry in developmental physiology, as they not only show lateralized functions but also show distinct left-right asymmetries in brain structure [116–119]. In Xenopus, however, no consistent marker of brain laterality has been described. The endogenous hyperpolarization described above is a convenient novel readout of neural asymmetry because it can be imaged in live animals and is thus compatible with behavioral testing and other experimental paradigms requiring the raising of animals with known neural laterality to older stages.

What is the link between the subtle asymmetries of neural derived organs and the main pathway that determines left-right asymmetry of the body? One of the fascinating aspects of left-right asymmetry determination is the disconnect between the sidedness of the major body organs and the brain. Human situs inversus patients (who exhibit complete reversal of the left-right body axis) show normal levels of right handedness and language lateralization [120, 121]. However, certain other behavioral traits (e.g., the hand on which the wristwatch is worn) are found to be reversed [7].

In zebrafish, the asymmetry of the diencephalic region, habenula and parapineal nuclei [116] were found to be reversed in situs inversus animals, along with a subset of their visual laterality behavior [110]. Moreover, it is now known that individual neurites have a consistent clockwise chirality of outgrowth [122] and turning [123]. Our data in Xenopus demonstrate the linkage of basic body asymmetry to the cryptic asymmetry of the eye: a treatment that randomized the major visceral organs also eliminated the right-side-first bias of the eye patterning signal, suggesting that the asymmetry of the eye derives from the same pathway that patterns the major left-right axis in Xenopus.

3.3. The Physiological Origin of the Asymmetry

What is responsible for the consistently different V mem in the left and right sides of the developing head? The KATP channel consists of Kir and SUR subunits and is responsible for setting resting potential in a number of cell types [124]. KATP channel activity depends on the resting V mem, ATP levels in the cell, the external potassium levels, and the limiting levels of each subunit. Our expression data (Figure 3, which extends and complements early immunohistochemistry data on KATP channels in the hatching gland, [125]) reveal a consistent left-right asymmetry in the levels of a transcript with homology to the mouse SUR KATP channel subunit. Comparison of the mouse SUR probe sequence to the completed Xenopus tropicalis genome using BLAST [126] gives matches with SUR1 (P = 2E − 10), SUR2 (P = 2E − 75), but no other target (the next best match is PGER2 at nonsignificant P = 0.39), which supports the high probability of the probe picking up a SUR-like mRNA in Xenopus laevis. While we have not yet identified the native transcript corresponding to this signal, the high specificity of the staining pattern and the stringency of the in situ hybridization conditions make it likely that the mouse probe of SUR is picking up a native SUR-like mRNA that has not yet been characterized within the incompletely sequenced X. laevis genome.

The observed asymmetry in the presence of SUR1 subunits is likely to result in a larger number of functional KATP channels on the side with greater SUR1 expression. On a background of equal initial V mem and external potassium levels on the left and right sides, the asymmetry in subunits available for the formation of functional KATP channels may explain the difference in the V mem on the left and right sides. It is possible that the asymmetry in functional KATP channels is also responsible for the observed asymmetry in sensitivity to eye malformation upon perturbing the V mem. Other channels may be involved in generating the observed asymmetric polarization. Comparative expression profiling and functional testing on both sides in the eye region may reveal other candidate/s that cooperate with KATP to generate the asymmetric polarization eye patterning signal.

The KATP subunits are expressed mainly in the surface ectoderm, which forms the eye placode. Interaction between the ectodermal placode and the underlying neuroectodermal and mesodermal layers results in invagination of the optic cup and eye formation [127–130]. The KATP ion channels in the surface ectoderm, and the bioelectric cell properties they regulate, may participate in modulating these signaling interactions.

One important feature of the observed bioelectric asymmetry is its temporal properties: although the right eye signal is seen first, the eye-specific V mem signature is ultimately seen on both sides (the left side delayed by 20–30 minutes), resulting in anatomically symmetrical and equal sized eyes. As the function of ion channels is gated by posttranslational events, physiological feedback loops implemented by voltage-sensitive channels could amplify stable differences in V mem, leading to distinct voltage gradients in cell groups expressing similar complements of ion channel proteins. Future work will profile the other major conductances present in eye cells and quantitatively characterize and model the molecular-genetic and temporal details of the circuit that functions in eye precursor cells to control resting potential. Such circuits are likely to exhibit distinct stable V mem states, as has been shown in mouse (muscle) cells to be due to potassium inward rectifying channels [131].

3.4. Neural Crest Derivatives Are Also Consistently Left-Right Asymmetric

A similar asymmetry was observed in neural crest-derived pigment cells, melanocytes. Melanocytes follow specific migration paths along the side of the Xenopus embryo after differentiation from neural crest. Interestingly, a consistent left-right asymmetry in the number of melanocytes was found upon careful analysis. Our analysis of Trp2-positive cells prior to onset of migration (stage 26) revealed that there is no apparent asymmetry in the extent of melanocyte differentiation from the neural crest cells, suggesting that the observed asymmetry is due to asymmetric migration patterns. The source of asymmetric migratory cues or mechanisms ensuring left-right asymmetrically biased response of cells to migration cues (as has been observed in mammalian cells [132, 133]) remains to be analyzed in future work. The evolutionary or developmental role of such asymmetric melanocyte distributions is not yet known; indeed, it is possible that careful quantification of cell number or other properties in other developmental events may reveal other heretofore-unrecognized consistent asymmetries in systems that are currently considered to be symmetrical.

3.5. Conclusion

The identification of subtle physiological and cell positioning asymmetries in Xenopus development raises a number of open questions. It is possible that consistent asymmetries in bioelectric state, cell number, and sensitivity to specific perturbations remain to be discovered in many different paired (symmetric) organs. The anatomical and genetic profiling studies carried out to date may have only scratched the surface of the developmental information embedded in various somatic tissues at the level of mRNA and protein profiles and would likely not reveal physiology differences. The identification of such asymmetries, as well as their molecular origins, and the characterization of their interactions with the major left-right axial patterning cascade are likely to reveal fascinating aspects of developmental biology with significant evolutionary implications. Moreover, a mechanistic understanding of these subtle asymmetries will provide insight into the form, function, and robustness of the nervous system and may help address the lateralized diseases of both nervous and nonnervous organs.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animal Husbandry

Xenopus laevis embryos were collected and fertilized in vitro according to standard protocols [134], in 0.1X Modified Marc's Ringers (MMR; pH 7.8). Xenopus embryos were housed at 14–18°C and staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber [135]. All experiments were approved by the Tufts University Animal Research Committee in accordance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, protocol number: M2011-70.

4.2. Imaging of Membrane Voltage Patterns Using CC2-DMPE

CC2-DMPE (molecular probes) stocks (stock: 1 mg/mL in DMSO) were diluted 1 : 1000 in 0.1X MMR for a final concentration of 0.2 μM. Stage 15–16 embryos were soaked in dye for 1.5 h. Embryos in solution were imaged using the CC2 cube set on an Olympus BX61 microscope with an ORCA digital CCD camera (Hamamatsu) with Metamorph software. See [66, 67] for additional details. For determining the bias in eye CC2-DMPE signal, embryos were imaged at regular intervals. The side of the embryo that first showed the eye CC2-DMPE signal was noted, and the embryos were kept under observation until signal was seen on both sides. Time difference between the right and left eye CC2-DMPE signals was measured by taking images at regular intervals of 10 minutes. While CC2-DMPE used alone cannot precisely quantify V mem levels, the strong fluorescence from this positively charged dye has been shown previously to reliably identify hyperpolarized regions as confirmed by electrophysiological impalement [65–67, 136] and to identify the same locations of hyperpolarized cells in the early face as did prior studies using ratiometric imaging [69].

4.3. Microinjection

Capped, synthetic mRNAs were generated using the Ambion mMessage mMachine kit, resuspended in water, and injected (2.7 nL per blastomere) into embryos in 3% Ficoll. Results of injections are reported as percentage of injected embryos showing eye phenotypes, sample size (n) and P values comparing treated groups to controls. For lineage tracing, 4-cell embryos were injected with mRNA encoding β-galactosidase. At stage 45, fixed embryos were stained by incubation with X-gal substrate.

4.4. In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed according to standard protocols [137]. Accession numbers for the sequences used as probes were Kir6.1 NM_008428.4, Kir6.2 NM_001204411.1, SUR1 NM_011510.3, and SUR2 NM_001044720.1. Xenopus embryos were collected and fixed in MEMFA. Prior to in situ hybridization, embryos were washed in PBS + 0.1% Tween-20 and then transferred to ethanol through a 25%/50%/75% series. In situ probes were generated in vitro from linearized templates using DIG labeling mix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Chromogenic reaction times were optimized to maximize signal and minimize background. Histological sections were obtained by embedding embryos after in situ hybridization in JB4 according to manufacturer's instructions (Polysciences). Prior to sectioning, one corner of the block was physically marked to allow unambiguous orientation of section images with respect to the left-right axis (for sections in Figure 3(b)).

4.4.1. Quantification of In Situ Signal

Trp2 in situ hybridized embryos were embedded in 4% low melting point agarose as previously described and sectioned at 100 μm [138]. The sections were imaged using a Nikon SMZ1500 microscope with a Q-imaging Retiga 2000R camera. Using NIH's ImageJ software the regions exhibiting purple signal on the left and right side of the sections were marked using the freehand selection tool, and the area of the Trp2 stain was automatically quantified. The 3rd section from the last section containing eye was selected from each of the 10 different embryos and used for quantification.

4.5. Heterotaxia-Inducing Treatment

Embryos were kept in 0.1X MMR (pH 4.0–4.05) from fertilization until stage 12-13 and then moved to 0.1x MMR (pH 7.8) for the remainder of the experiment. At stage 45, the situs of the internal organs was scored by visual inspection of the heart, gut, and gallbladder as previously reported [17]. Categorical data analysis of the CC2-DMPE staining following drug treatment was done using ternary plots [75].

4.6. Retinoic Acid Receptor Inhibitor (Ro-41-5253) Treatment

Embryos were kept in 0.1X MMR from fertilization. At ~ stage 11 Ro-41-5253 was added into 0.1X MMR with a final concentration of 1.5 μM. At stage 18, a portion of the embryos were fixed and used for in situ hybridization. Categorical data analysis of the CC2-DMPE staining following drug treatment was done on the remaining live embryos using ternary plots [75].

4.7. Statistics

All Statistical analyses were performed using Graphpad Prism (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA), except in case of the categorical data analyses where ternary plots algorithms were used (https://webscript.princeton.edu/~rburdine/stat/three_categories). For data pooled from various iterations, Chi-square test or two-tailed Binomial calculation was used. Nonpooled data was analyzed by t-test (for 2 groups) or ANOVA (for more than two groups).

Authors' Contribution

V. P. Pai and M. Levin designed research, V. P. Pai, M. Levin, L. N. Vandenberg, and D. Blackiston performed research, and M. Levin and V. P. Pai wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Punita Koustubhan, Amber Currier, Joan Lemire, and Claire Stevenson for Xenopus husbandry and general lab assistance and Daryl Davies and Miriam Fine for the GlyCl expression construct. They also especially thank Dany S. Adams and Brook Chernet for microscopy assistance and Sherry Aw for many helpful ideas and discussions on this project. This work was supported by NIH Grants EY018168, MH081842, and GM077425 to M. Levin. The authors are also grateful for the support of the G. Harold and Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation.

References

- 1.Neville AC. Animal Asymmetry. London, UK: Edward Arnold; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer AR. From symmetry to asymmetry: phylogenetic patterns of asymmetry variation in animals and their evolutionary significance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93(25):14279–14286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peeters H, Devriendt K. Human laterality disorders. European Journal of Medical Genetics. 2006;49(5):349–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ramsdell AF. Left-right asymmetry and congenital cardiac defects: getting to the heart of the matter in vertebrate left-right axis determination. Developmental Biology. 2005;288(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisgrove BW, Morelli SH, Yost HJ. Genetics of human laterality disorders: insights from vertebrate model systems. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2003;4:1–32. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.4.070802.110428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus I. Right Hand, Left Hand: The Origins of Asym metry in Brains, Bodies, Atoms and Cultures. Harvard University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 7.McManus IC, Martin N, Stubbings GF, Chung EMK, Mitchison HM. Handedness and situs inversus in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 2004;271(1557):2579–2582. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2004.2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vandenberg LN, Levin M. Far from solved: a perspective on what we know about early mechanisms of left-right asymmetry. Developmental Dynamics. 2010;239(12):3131–3146. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levin M. Left-right asymmetry in embryonic development: a comprehensive review. Mechanisms of Development. 2005;122(1):3–25. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spéder P, Petzoldt A, Suzanne M, Noselli S. Strategies to establish left/right asymmetry in vertebrates and invertebrates. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2007;17(4):351–358. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun T, Walsh CA. Molecular approaches to brain asymmetry and handedness. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7(8):655–662. doi: 10.1038/nrn1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basu B, Brueckner M. Chapter Six Cilia. Multifunctional organelles at the center of vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2008;85:151–174. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00806-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harvey RP. Links in the left/right axial pathway. Cell. 1998;94(3):273–276. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81468-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aw S, Adams DS, Qiu D, Levin M. H,K-ATPase protein localization and Kir4.1 function reveal concordance of three axes during early determination of left-right asymmetry. Mechanisms of Development. 2008;125(3-4):353–372. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danilchik MV, Brown EE, Riegert K. Intrinsic chiral properties of the Xenopus egg cortex: an early indicator of left-right asymmetry. Development. 2006;133(22):4517–4526. doi: 10.1242/dev.02642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pohl C. Left-right patterning in the C. elegans embryo: unique mechanisms and common principles. Communicative and Integrative Biology. 2011;4(1):34–40. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.1.14144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adams DS, Robinson KR, Fukumoto T, et al. Early, H+-V-ATPase-dependent proton flux is necessary for consistent left-right patterning of non-mammalian vertebrates. Development. 2006;133(9):1657–1671. doi: 10.1242/dev.02341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levin M, Thorlin T, Robinson KR, Nogi T, Mercola M. Asymmetries in H+/K+-ATPase and cell membrane potentials comprise a very early step in left-right patterning. Cell. 2002;111(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raya Á, Kawakami Y, Rodríguez-Esteban C, et al. Notch activity acts as a sensor for extracellular calcium during vertebrate left-right determination. Nature. 2004;427(6970):121–128. doi: 10.1038/nature02190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garic-Stankovic A, Hernandez M, Flentke GR, Zile MH, Smith SM. A ryanodine receptor-dependent Cai2+ asymmetry at Hensen's node mediates avian lateral identity. Development. 2008;135(19):3271–3280. doi: 10.1242/dev.018861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kreiling JA, Balantac ZL, Crawford AR, et al. Suppression of the endoplasmic reticulum calcium pump during zebrafish gastrulation affects left-right asymmetry of the heart and brain. Mechanisms of Development. 2008;125(5-6):396–410. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sienknecht U. Genetic stabilization of vertebrate bilateral limb symmetry as an example of cryptic polarity. Developmental Biology. 2006;295:414–415. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klingenberg CP, McIntyre GS, Zaklan SD. Left-right asymmetry of fly wings and the evolution of body axes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 1998;265(1413):p. 2455. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klingenberg CP, McIntyre GS, Zaklan SD. Left-right asymmetry of fly wings and the evolution of body axes. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 1998;265:1255–1259. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1998.0427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy J, Levy JM. Human lateralization from head to foot: sex-related factors. Science. 1978;200(4347):1291–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.663611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittwoch U. Genetics of mammalian sex determination: some unloved exceptions. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 2001;290(5):484–489. doi: 10.1002/jez.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klingenberg CP, Mcintyre GS. Geometric morphometrics of developmental instability: analyzing patterns of fluctuating asymmetry with procrustes methods. Evolution. 1998;52(5):1363–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Angelopoulou MV, Vlachou V, Halazonetis DJ. Fluctuating molar asymmetry in relation to environmental radioactivity. Archives of Oral Biology. 2009;54(7):666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vilhais-Neto GC, Maruhashi M, Smith KT, et al. Rere controls retinoic acid signalling and somite bilateral symmetry. Nature. 2010;463(7283):953–957. doi: 10.1038/nature08763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vermot J, Pourquié O. Retinoic acid coordinates somitogenesis and left-right patterning in vertebrate embryos. Nature. 2005;435(7039):215–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saúde L, Lourenço R, Gonçalves A, Palmeirim I. terra is a left-right asymmetry gene required for left-right synchronization of the segmentation clock. Nature Cell Biology. 2005;7(9):918–920. doi: 10.1038/ncb1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Golding JP, Partridge TA, Beauchamp JR, et al. Mouse myotomes pairs exhibit left-right asymmetric expression of MLC3F and α-skeletal actin. Developmental Dynamics. 2004;231(4):795–800. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Golding JP, Tsoni S, Dixon M, et al. Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor shows transient left-right asymmetrical expression in mouse myotome pairs. Gene Expression Patterns. 2004;5(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milaire J. Histological changes induced in developing limb buds of C57BL mouse embryos submitted in utero to the combined influence of acetazolamide and cadmium sulphate. Teratology. 1985;32(3):433–451. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420320313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barr M., Jr. The teratogenicity of cadmium chloride in two stocks of Wistar rats. Teratology. 1973;7(3):237–242. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420070304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Layton WM, Jr., Layton MW. Cadmium induced limb defects in mice: strain associated differences in sensitivity. Teratology. 1979;19(2):229–235. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420190213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith AT, Sack GH, Taylor GJ. Holt-oram syndrome. Journal of Pediatrics. 1979;95(4):538–543. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80758-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delaney M, Boyd TK. Case report of unilateral clefting: is sonic hedgehog to blame? Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 2007;10(2):117–120. doi: 10.2350/06-03-0063.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paulozzi LJ, Lary JM. Laterality patterns in infants with external birth defects. Teratology. 1999;60(5):265–271. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199911)60:5<265::AID-TERA7>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Newbury-Ecob RA, Leanage R, Raeburn JA, Young ID. Holt-Oram syndrome: a clinical genetic study. Journal of Medical Genetics. 1996;33(4):300–307. doi: 10.1136/jmg.33.4.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatcher CJ, Goldstein MM, Mah CS, Delia CS, Basson CT. Identification and localization of TBX5 transcription factor during human cardiac morphogenesis. Developmental Dynamics. 2000;219(1):90–95. doi: 10.1002/1097-0177(200009)219:1<90::AID-DVDY1033>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruneau BG, Logan M, Davis N, et al. Chamber-specific cardiac expression of Tbx5 and heart defects in Holt- Oram syndrome. Developmental Biology. 1999;211(1):100–108. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewin SO, Opitz JM. Fibular a/hypoplasia: review and documentation of the fibular developmental field. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Supplement. 1986;2:215–238. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levin M, Mercola M. Gap junction-mediated transfer of left-right patterning signals in the early chick blastoderm is upstream of Shh asymmetry in the node. Development. 1999;126(21):4703–4714. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clericuzio CL. Clinical phenotypes and Wilms tumor. Medical and Pediatric Oncology. 1993;21(3):182–187. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950210306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fraumeni JF, Jr., Geiser CF, Manning MD. Wilms' tumor and congenital hemihypertrophy: report of five new cases and review of literature. Pediatrics. 1967;40(5):886–899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoyme HE, Seaver LH, Jones KL, et al. Isolated hemihyperplasia (hemihypertrophy): report of a prospective multicenter study of the incidence of neoplasia and review. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 1998;79:274–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albertson RC, Yelick PC. Roles for fgf8 signaling in left-right patterning of the visceral organs and craniofacial skeleton. Developmental Biology. 2005;283(2):310–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Niehrs C. On growth and form: a Cartesian coordinate system of Wnt and BMP signaling specifies bilaterian body axes. Development. 2010;137(6):845–857. doi: 10.1242/dev.039651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanodia JS, Rikhy R, Kim Y, et al. Dynamics of the Dorsal morphogen gradient. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106(51):21707–21712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912395106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beloussov LV. Mechanically based generative laws of morphogenesis. Physical Biology. 2008;5(1) doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/5/1/015009.015009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beloussov LV, Grabovsky VI. Morphomechanics: goals, basic experiments and models. International Journal of Developmental Biology. 2006;50(2-3):81–92. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052056lb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sundelacruz S, Levin M, Kaplan DL. Role of membrane potential in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2009;5(3):231–246. doi: 10.1007/s12015-009-9080-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Blackiston DJ, McLaughlin KA, Levin M. Bioelectric controls of cell proliferation: ion channels, membrane voltage and the cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2009;8(21):3519–3528. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.21.9888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levin M. Errors of Geometry: regeneration in a broader perspective. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2009;20(6):643–645. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCaig CD, Song B, Rajnicek AM. Electrical dimensions in cell science. Journal of Cell Science. 2009;122(23):4267–4276. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCaig CD, Rajnicek AM, Song B, Zhao M. Controlling cell behavior electrically: current views and future potential. Physiological Reviews. 2005;85(3):943–978. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00020.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Levin M. Molecular bioelectricity In developmental biology: new tools and recent discoveries. BioEssays. 2011;34(3):205–217. doi: 10.1002/bies.201100136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams DS. A new tool for tissue engineers: ions as regulators of morphogenesis during development and regeneration. Tissue Engineering A. 2008;14(9):1461–1468. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nogi T, Yuan YE, Sorocco D, Perez-Tomas R, Levin M. Eye regeneration assay reveals an invariant functional left-right asymmetry in the early bilaterian, Dugesia japonica. Laterality. 2005;10(3):193–205. doi: 10.1080/1357650054200001440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lange C, Prenninger S, Knuckles P, Taylor V, Levin M, Calegari F. The H+ vacuolar ATPase maintains neural stem cells in the developing mouse cortex. Stem Cells and Development. 2011;20(5):843–850. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blackiston D, Adams DS, Lemire JM, Lobikin M, Levin M. Transmembrane potential of GlyCl-expressing instructor cells induces a neoplastic-like conversion of melanocytes via a serotonergic pathway. DMM Disease Models and Mechanisms. 2011;4(1):67–85. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Beane WS, Morokuma J, Adams DS, Levin M. A chemical genetics approach reveals H,K-ATPase-mediated membrane voltage is required for planarian head regeneration. Chemistry and Biology. 2011;18(1):77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tseng AS, Beane WS, Lemire JM, Masi A, Levin M. Induction of vertebrate regeneration by a transient sodium current. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(39):13192–13200. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3315-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Adams DS, Masi A, Levin M. H+ pump-dependent changes in membrane voltage are an early mechanism necessary and sufficient to induce Xenopus tail regeneration. Development. 2007;134(7):1323–1335. doi: 10.1242/dev.02812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adams DS, Levin M. Measuring resting membrane potential using the fluorescent voltage reporters DiBAC4(3) and CC2-DMPE. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2012;2012(4):459–464. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot067702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Adams DS, Levin M. General principles for measuring resting membrane potential and ion concentration using fluorescent bioelectricity reporters. Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2012;2012(4):385–397. doi: 10.1101/pdb.top067710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pai VP, Aw S, Shomrat T, Lemire JM, Levin M. Transmembrane voltage potential conrols embryonic eye patterning in Xenopus laevis. Development. 2012;139(2):313–323. doi: 10.1242/dev.073759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vandenberg LN, Morrie RD, Adams DS. V-ATPase-dependent ectodermal voltage and Ph regionalization are required for craniofacial morphogenesis. Developmental Dynamics. 2011;240(8):1889–1904. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Adams DS, Levin M. Endogenous voltage gradients as mediators of cell-cell communication: strategies for investigating bioelectrical signals during pattern formation. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1329-4. Cell and Tissue Research. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wolff C, Fuks B, Chatelain P. Comparative study of membrane potential-sensitive fluorescent probes and their use in ion channel screening assays. Journal of Biomolecular Screening. 2003;8(5):533–543. doi: 10.1177/1087057103257806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oviedo NJ, Nicolas CL, Adams DS, Levin M. Live imaging of planarian membrane potential using DiBAC4(3) Cold Spring Harbor Protocols. 2008;3(10) doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brend T, Holley SA. Balancing segmentation and laterality during vertebrate development. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2009;20(4):472–478. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Franco PG, Paganelli AR, Löpez SL, Carrasco AE. Functional association of retinoic acid and hedgehog signaling in Xenopus primary neurogenesis. Development. 1999;126(19):4257–4265. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Xu B, Feng X, Burdine RD. Categorical data analysis in experimental biology. Developmental Biology. 2010;348(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yost HJ. Development of the left-right axis in amphibians. Ciba Foundation Symposium. 1991;162:165–176. doi: 10.1002/9780470514160.ch10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Danos MC, Yost HJ. Linkage of cardiac left-right asymmetry and dorsal-anterior development in Xenopus. Development. 1995;121(5):1467–1474. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Levin M. Is the early left-right axis like a plant, a kidney, or a neuron? The integration of physiological signals in embryonic asymmetry. Birth Defects Research C. 2006;78(3):191–223. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Davies DL, Trudell JR, Mihic SJ, Crawford DK, Alkana RL. Ethanol potentiation of glycine receptors expressed in xenopus oocytes antagonized by increased atmospheric pressure. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2003;27(5):743–755. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000065722.31109.A1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Shan Q, Haddrill JL, Lynch JW. Ivermectin, an unconventional agonist of the glycine receptor chloride channel. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(16):12556–12564. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011264200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lobikin M, Wang G, Xu J, et al. Early, nonciliary role for microtubule proteins in left-right patterning is conserved across kingdoms. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:12586–12591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202659109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Oviedo NJ, Levin M. Gap junctions provide new links in left-right patterning. Cell. 2007;129(4):645–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Levin M, Mercola M. Gap junctions are involved in the early generation of left-right asymmetry. Developmental Biology. 1998;203(1):90–105. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Levin M, Mercola M. Gap junction-mediated transfer of left-right patterning signals in the early chick blastoderm is upstream of Shh asymmetry in the node. Development. 1999;126(21):4703–4714. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.21.4703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carneiro K, Donnet C, Rejtar T, et al. Histone deacetylase activity is necessary for left-right patterning during vertebrate development. BMC Developmental Biology. 2011;11, article 29 doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schweickert A, Weber T, Beyer T, et al. Cilia-driven leftward flow determines laterality in xenopus. Current Biology. 2007;17(1):60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pai VP, Aw S, Shomrat T, Lemire JM, Levin M. Transmembrane voltage potential controls embryonic eye patterning in Xenopus laevis. Development. 2012;139:313–323. doi: 10.1242/dev.073759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Moody SA. Fates of the blastomeres of the 32-cell-stage Xenopus embryo. Developmental Biology. 1987;122(2):300–319. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(87)90296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chow RL, Altmann CR, Lang RA, Hemmati-Brivanlou A. Pax6 induces ectopic eyes in a vertebrate. Development. 1999;126(19):4213–4222. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Aydar E, Yeo S, Djamgoz M, Palmer C. Abnormal expression, localization and interaction of canonical transient receptor potential ion channels in human breast cancer cell lines and tissues: a potential target for breast cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Cell International. 2009;9, article 23 doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Novak AE, Taylor AD, Pineda RH, Lasda EL, Wright MA, Ribera AB. Embryonic and larval expression of zebrafish voltage-gated sodium channel α-subunit genes. Developmental Dynamics. 2006;235(7):1962–1973. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jones SM, Ribera AB. Overexpression of a potassium channel gene perturbs neural differentiation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1994;14(5):2789–2799. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02789.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440(7083):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Aw S, Koster JC, Pearson W, et al. The ATP-sensitive K+-channel (KATP) controls early left-right patterning in Xenopus and chick embryos. Developmental Biology. 2010;346(1):39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aw S, Koster JC, Pearson W, et al. The ATP-sensitive K+-channel (KATP) controls early left-right patterning in Xenopus and chick embryos. Developmental Biology. 2010;346(1):39–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kumasaka M, Sato S, Yajima I, Yamamoto H. Isolation and developmental expression of tyrosinase family genes in Xenopus laevis. Pigment Cell Research. 2003;16(5):455–462. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Proshchina AE, Savel'ev SV. Study of amphibian brain asymmetry during normal embryonic and larval development. Izvestiia Akademii Nauk. 1998;(3):408–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bao B, Ke Z, Xing J, et al. Proliferating cells in suborbital tissue drive eye migration in flatfish. Developmental Biology. 2011;351(1):200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yoshida K, Saiga H. Repression of Rx gene on the left side of the sensory vesicle by Nodal signaling is crucial for right-sided formation of the ocellus photoreceptor in the development of Ciona intestinalis. Developmental Biology. 2011;354(1):144–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Trelstad RL, Coulombre AJ. Morphogenesis of the collagenous stroma in the chick cornea. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1971;50(3):840–858. doi: 10.1083/jcb.50.3.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Coulombre AJ. Experimental embryology of the vertebrate eye. Investigative ophthalmology. 1965;4:411–419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Trelstad RL. The bilaterally asymmetrical architecture of the submammalian corneal stroma resembles a cholesteric liquid crystal. Developmental Biology. 1982;92(1):133–134. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.MacNeilagea PF, Studdert-Kennedya MG, Lindbloma B. Primate Handedness reconsidered. Behavioral and Brain Science. 1987;10(2):247–303. [Google Scholar]

- 104.Vallortigara G, Rogers LJ. Survival with an asymmetrical brain: advantages and disadvantages of cerebral lateralization. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2005;28(4):575–589. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rashid N, Andrew RJ. Right hemisphere advantage for topographical orientation in the domestic chick. Neuropsychologia. 1989;27(7):937–948. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(89)90069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rogers LJ, Andrew RJ, Burne THJ. Light exposure of the embryo and development of behavioural lateralisation in chicks, I: olfactory responses. Behavioural Brain Research. 1998;97(1-2):195–200. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lippolis G, Bisazza A, Rogers LJ, Vallortigara G. Lateralisation of predator avoidance responses in three species of toads. Laterality. 2002;7(2):163–183. doi: 10.1080/13576500143000221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Vallortigara G, Rogers LJ, Bisazza A, Lippolis G, Robins A. Complementary right and left hemifield use for predatory and agonistic behaviour in toads. NeuroReport. 1998;9(14):3341–3344. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199810050-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Bisazza A, De Santi A, Bonso S, Sovrano VA. Frogs and toads in front of a mirror: lateralisation of response to social stimuli in tadpoles of five anuran species. Behavioural Brain Research. 2002;134(1-2):417–424. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(02)00055-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Vallortigara G, Rogers LJ, Bisazza A. Possible evolutionary origins of cognitive brain lateralization. Brain Research Reviews. 1999;30(2):164–175. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chang C, Hsieh YW, Lesch BJ, Bargmann CI, Chuang CF. Microtubule-based localization of a synaptic calciumsignaling complex is required for left-right neuronal asymmetry in C. elegans. Development. 2011;138(16):3509–3518. doi: 10.1242/dev.069740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Chuang CF, VanHoven MK, Fetter RD, Verselis VK, Bargmann CI. An Innexin-Dependent Cell Network Establishes Left-Right Neuronal Asymmetry in C. elegans. Cell. 2007;129(4):787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bauer Huang SL, Saheki Y, VanHoven MK, et al. Left-right olfactory asymmetry results from antagonistic functions of voltage-activated calcium channels and the Raw repeat protein OLRN-I in C. elegans . Neural Development. 2007;2(1, article 24) doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.VanHoven MK, Bauer Huang SL, Albin SD, Bargmann CI. The claudin superfamily protein NSY-4 biases lateral signaling to generate left-right asymmetry in C. elegans Olfactory Neurons. Neuron. 2006;51(3):291–302. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Poole RJ, Hobert O. Early Embryonic Programming of Neuronal Left/Right Asymmetry in C. elegans. Current Biology. 2006;16(23):2279–2292. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Concha ML, Wilson SW. Asymmetry in the epithalamus of vertebrates. Journal of Anatomy. 2001;199(1-2):63–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19910063.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Barth KA, Miklosi A, Watkins J, Bianco IH, Wilson SW, Andrew RJ. fsi zebrafish show concordant reversal of laterality of viscera, neuroanatomy, and a subset of behavioral responses. Current Biology. 2005;15(9):844–850. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Facchin L, Burgess HA, Siddiqi M, Granato M, Halpern ME. Determining the function of zebrafish epithalamic asymmetry. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2009;364(1519):1021–1032. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Facchin L, Argenton F, Bisazza A. Lines of Danio rerio selected for opposite behavioural lateralization show differences in anatomical left-right asymmetries. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;197(1):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kennedy DN, O’Craven KM, Ticho BS, Goldstein AM, Makris N, Henson JW. Structural and functional brain asymmetries in human situs inversus totalis. Neurology. 1999;53(6):1260–1265. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tanaka S, Kanzaki R, Yoshibayashi M, Kamiya T, Sugishita M. Dichotic listening in patients with situs inversus:Brain asymmetry and situs asymmetry. Neuropsychologia. 1999;37(7):869–874. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(98)00144-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Heacock AM, Agranoff BW. Clockwise growth of neurites from retinal explants. Science. 1977;198(4312):64–66. doi: 10.1126/science.897684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tamada A, Kawase S, Murakami F, Kamiguchi H. Autonomous right-screw rotation of growth cone filopodia drives neurite turning. Journal of Cell Biology. 2010;188(3):429–441. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200906043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Babenko AP, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. A view of SUR/K(IR)6.X, k(atp) channels. Annual Review of Physiology. 1998;60:667–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Cheng SM, Chen I, Levin M. KATP channel activity is required for hatching in Xenopus embryos. Developmental Dynamics. 2002;225(4):588–591. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zuber ME. Eye field specification in Xenopus laevis. Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2010;93:29–60. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385044-7.00002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]