Abstract

Food is important to any animal, and a large part of the behavioral repertoire is concerned with ensuring adequate nutrition. Two main nutritional sensations, hunger and satiety, produce opposite behaviors. Hungry animals seek food, increase exploratory behavior and continue feeding once they encounter food. Satiated animals decrease exploratory behavior, take rest, and stop feeding. The signals of hunger or satiety and their effects on physiology and behavior will depend not only on the animal’s current nutritional status but also on its experience and the environment in which the animal evolved. In our novel, nutritionally rich environment, improper control of appetite contributes to diseases from anorexia to the current epidemic of obesity. Despite extraordinary recent advances, genetic contribution to appetite control is still poorly understood partly due to lack of simple genetic model systems. In this review, we will discuss current understanding of molecular and cellular mechanisms by which animals regulate food intake depending on their nutritional status. Then, focusing on relatively less known muscarinic and cGMP signals, we will discuss how the molecular and behavioral aspects of hunger and satiety are conserved in a simple invertebrate model system, C. elegans so as for us to use it to understand the genetics of appetite control.

Keywords: appetite control, muscarinic signaling, cGMP, food intake, C. elegans

1. Introduction: Feeding behavior determined by nutritional status

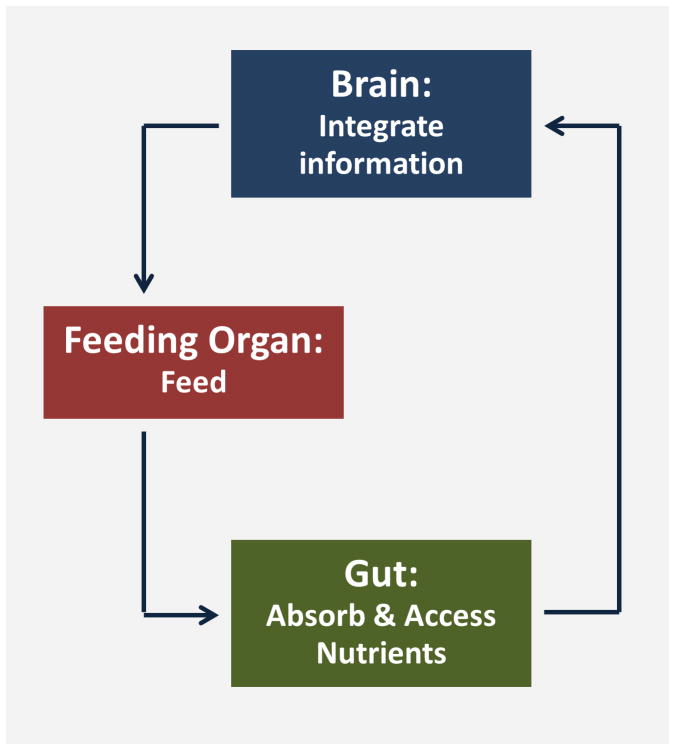

Hunger and satiety produce opposite effects not only on feeding but also on many other behaviors such as food seeking or sleep. This suggests that the sensation of nutritional status, which very likely happens in the digestive track (gut), reaches the nervous system (brain) to direct appropriate behaviors: eat or stop eating or look around for food or stop moving around and rest. Thus there are at least three parts of the body that are interconnected to regulate feeding: brain (or something equivalent), gut and feeding organs. Figure 1 shows a simplified diagram of a feeding circuit; when an animal eats, the gut absorbs the nutrients, then sends specific signals to the brain where they are integrated to direct feeding behavior. When an animal is hungry, hunger evokes signals from the gut, then the brain directs the feeding organ to eat. Therefore the signals from the gut and their integration in the brain are the most important for feeding regulation.

Figure 1.

A simplified diagram of a feeding circuit: When an animal eats, the gut absorbs the nutrients, then sends specific signals to the brain where they are integrated to direct feeding organ and behavior.

1.1. Brain

In 1940, Hetherington and Ransom used the Horsley-Clarke sterotaxis apparatus to introduce bilateral lesions in the hypothalamus of rats (Hetherington and Ranson 1940). The striking results were described as:

A condition of marked adiposity characterized by as much as a doubling of body weight and a tremendous increase of extractable body lipids has been produced in rats by the placing of electrolytic lesions in the hypothalamus.

They found that removing a small part of the hypothalamus changes feeding behavior entirely, resulting in increase of food intake, body weight and adiposity. They also observed that removing the adjacent part evokes the opposite effect: the rats don’t eat and starve to death. Later these locations were defined based on the specific molecular mechanisms and discrete neuronal pathways by which food intake is regulated. The ventromedial hypothalamus whose lesions resulted in hyperphagia (increase of feeding) contains pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) expressing neurons. The lateral hypothalamus whose lesion resulted in hypophasia (decrease of feeding) contains neuropeptide Y/agouti-related protein (NPY/AgRP) expressing neurons. When POMC neurons get activated, they release POMC so that animals eat less. On the other hand, when NPY/AgRP neurons get activated, they release NPY/AgRP and animals eat more (Schwartz et al. 2000). Interestingly, when NPY/AgRP neurons get activated, they directly inhibit POMC neurons and if POMC neurons get activated, they inhibit NPY/AgRP neurons. This proximity of two loci of orexigenic and anorexigenic centers and their tight antagonism for each other show that this part of the hypothalamus has evolved to integrate food intake signals.

1.2. Gut

Which molecules activate or inhibit the neurons in the appetite control centers to regulate food intake? The neurons respond to circulating satiety and hunger signals many of which are released from gut or storage tissues such as adipose tissue. Some are peptide hormones that can elicit specific signaling cascades upon binding to their receptors in the brain, the appetite control center in the hypothalamus in particular (Murphy and Bloom 2006). (Table 1 shows some examples of the peptide hormones released from gut or brain to regulate hunger or satiety.) Others can be actual metabolites, such as oleoylethanolamide (OEA), produced from oleic acid (one of the most abundant ingredients of olive oil), that are tightly linked to an animal’s metabolic status (Schwartz et al. 2008).

Table 1.

Appetite control signals

| Hunger (origin) | Satiety (origin) |

|---|---|

| Galanin (brain) | Cholecystokinin (intestine) |

| Agouti-related protein (AGRP) (brain) | Bombesin family (bombesin, gastrin releasing peptide or GRP, and neuromedin B) (intestine) |

| Neuropeptide Y (NPY) (brain) | Glucagon (intestine) |

| Melanin concentrating hormone (MCH) (brain) | Glucagon-like peptides 1 and 2 (intestine) |

| Orexin a and b (brain) | Apolipoprotein A-IV (adipose tissue) |

| Peptide YY (PYY) (brain) | Amylin (intestine) |

| Ghrelin (stomach) | Uroguanylin (intestine) |

| Acetylcholine (?) | Cocaine and amphetamine regulated transcript (CART) (brain) |

| Somatostatin (brain) | |

| α-Melanocyte-Stimulating Hormone (α-MSH) (brain) | |

| pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) (brain) |

Several original studies of how an animal becomes sated found circulating signaling molecules from the gut. For instance, in their discovery of cholecystokinin (CCK) as a satiety signal, Gibbs and others found that ingested food didn’t evoke satiety unless it accumulated and was passed into the small intestine. (Gibbs et al. 1973a; Gibbs et al. 1973b). A rat’s duodenum was cut, linked to a tube and directed to the outside (called a gastric fistula). When the fistula was closed, the rats’ behavior displayed satiety, but when it was open, they didn’t stop eating. Although the food was tasted and swallowed, the animal kept eating unless the stomach was full and the food reached the small intestine. This result suggests that for the animal to feel satiated, nutrients have to reach the gut to be sensed. And then a signal is sent to the brain to relay the nutritional satisfaction. This proves that nutrition absorption in the gut is a part of the satiety circuitry and that certain signals need to be sent to the brain to inform it of the animal’s nutritional status so that the brain can decide whether to continue to eat.

In 1994, Zhang et al found that deficiency of a single gene ob, which encodes leptin, can cause misregulation of appetite, subsequent over-eating and obesity in mouse (Zhang et al. 1994). Later the same genetic deficiency was discovered to cause obesity in humans (Montague et al. 1997), confirming the conservation of the signal and its role in appetite-control behavior. Obesity is completely cured by injecting synthetic leptin (Farooqi et al. 2002), demonstrating that the abnormal feeding behavior is a monogenic trait and suggesting that appetite is controlled by genetic programs. Nonetheless, so far only a handful of genes have been discovered to regulate appetite. It is important to develop a simple genetic model system where the feeding behavior, the molecular mechanisms for sensing nutrition, and metabolism of fat and glucose are conserved, so as to quickly and easily find more genes that regulate appetite.

2. Appetite control: worm’s-eye-view

Recent studies have revealed many molecular pathways that regulate hunger and satiety. Good reviews discuss well known appetite control molecules such as ghrelin, CCK and leptin (Elmquist et al. 1999; Asakawa et al. 2001; Inui 2001; Moran and Kinzig 2004). So in this review we will focus on two hunger and satiety signals, muscarinic and cGMP signals, which are relatively less known but still conserved throughout the animals.

2.1. Why C. elegans?

C. elegans has been used as a powerful genetic model system to discover many complex yet evolutionarily conserved molecular pathways such as cell death (Ellis and Horvitz 1986; Horvitz et al. 1994). It has many features to be a powerful genetic model system. It is a self-fertilizing hermaphrodite that produces approximately 300 progeny in 3 days. The body length of an adult is approximately 1 mm so more than 200 adults can be easily fit in a 60 mm petridish. The cost to maintain them is cheap. This big brood size in combination with short life span, small size and cheap maintenance makes a genetic screening of millions of worms to get mutants easily achievable.

Ashrafi and others provided genetic evidence that fat metabolism and energy expenditure mechanisms are also conserved between worms and mammals (Ashrafi et al. 2003; Ashrafi 2007). Others have shown that C. elegans insulin signaling is involved in determining life span and in regulating fat storage (Kenyon et al. 1993; Kimura et al. 1997), showing high conservation with mammalian insulin signaling in both its molecular components and mechanism. Many proteins involved in regulation of fat metabolism in mammals were discovered to have worm homologs with conserved functions in fat storage: a worm homolog of AMPK, aak-2 and a nuclear hormone receptor homolog, nhr-49, regulate life span and fat storage (Apfeld et al. 2004; Van Gilst et al. 2005). Furthermore, neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine known to be important in high-level control of mammalian feeding are also important in worm metabolism, feeding and fat storage (Sze et al. 2000; Chase et al. 2004; Suo et al. 2009; Ezcurra et al. 2011). These findings show that worms and mammals share common mechanisms for signaling, metabolism and even information processing for energy homeostasis and fat metabolism. This suggests that food intake signals, which are closely integrated with energy metabolism and feeding control in mammals, could be conserved in worms. Here we describe worm hunger and satiety responses based on our own discoveries, showing that signals and food intake behavior are also conserved between worms and mammals.

2.2. The muscarinic pathway as a hunger signal

Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter that is widely distributed in the nervous system, including many brain regions. Also it is a neurotransmitter at the neuromuscular junction to contract muscle in most animals (Hayes and Riker 1963; Mitchell and Silver 1963). It acts through two types of receptors, nicotinic and muscarinic receptors (Stroud and Finer-Moore 1985; Wess 1993). In 1977, Chance and Lints showed that injecting a muscarinic agonist in an animal’s brain stimulates feeding through a mechanism that probably involves the feeding center in hypothalamus (Chance and Lints 1977). One possible molecular mechanism was suggested when the Wess group found that mice lacking M3, one of five muscarinic receptors, eat less and become small (Yamada et al. 2001). Later however, the same group found that the brain specific knock out of M3 receptors produced small mice but didn’t significantly change food intake (Gautam et al. 2009). Still, other pharmacological studies in which patients became obese after taking anti-psychopathological drugs that antagonize M3 receptors support the role of an M3 muscarinic signal in increasing food intake (Weston-Green et al. 2011). In combination, the M3 total body knockout results and the pharmacological studies suggest that M3 receptors controls food intake through a site other than the brain, although this mechanism may act in combination with the function in the brain. This is not surprising because M3 is expressed widely in the body, including the intestine, beta cells and vagus nerve. The vagus nerve is particularly interesting because it is the nerve that provides connections between the brain and the gut through afferent and hormonal signals that regulate fullness and satiety (Martin and Earle 2011). Vagotomy (cutting of the vagus nerve) improved long term weight loss, also suggesting its role in food intake (Kral et al. 1993).

We have found that the muscarinic pathway also regulates food intake in worms: a muscarinic receptor similar to the mammalian M3 receptor acts through a MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase) signaling pathway to regulate hunger responses (You et al. 2006). As described above, hunger is the internal state that results from starvation and that motivates not just feeding but the entire panoply of behavioral responses, such as food seeking. When we measured the rate of feeding motion (called pumping), wild type worms initially pumped slowly in the absence of food, but they increased the pumping rate gradually in the first 2 hours of starvation, probably in order to sample the environment in search for food. When the muscarinic receptor → MPK-1 pathway was blocked with a mutation in the receptor, the increase in pumping rate was reduced. Conversely, in gpb-2 mutants, in which the muscarinic receptor → MPK-1 is hyperactive due to lack of a negative regulator, pumping rate increases on starvation to a greater extent than in wild type. Moreover, the muscarinic receptor → MPK-1 pathway causes pharyngeal muscle to undergo specialized changes during starvation. And these changes in pharyngeal muscle during starvation may prepare worms to ingest food better when they, encounter food later. These data suggest that activation of the muscarinic receptor during starvation contributes to the increase in starvation-induced pharyngeal activity as a hunger response in worms.

2.3. The cGMP pathway as a satiety signal

cGMP signaling regulates many behaviors related to food seeking in invertebrates. In Drosophila, there are two natural variants of the PKG (cGMP-dependent protein kinase) gene causing two different feeding behaviors: rover and sitter (Osborne et al. 1997). Sitters don’t move around while rovers move a lot, and this foraging or food-seeking activity correlates with the activity of the PKG gene. Similar trends were discovered in honeybees and worms (Ben-Shahar et al. 2002; Fujiwara et al. 2002; Raizen et al. 2008). PKG activity correlates with locomotive activity, which usually represents explorative and food seeking behavior. Yet, its roles in food intake in mammals were only recently unveiled by Valentino et al, who found that the mice lacking the uroguanylin gene, which encodes a ligand for a membrane bound guanylate cyclase which produces cGMP, became obese (Valentino et al. 2011). They also found that the uroguanylin-GUCY2C (the receptor) system works as a canonical satiety signaling system: UROGUANYLIN is released from the gut to bind GUCY2C in hypothalamus. This novel cGMP signaling pathway of appetite control in mammals proves strong conservation in the control of food intake by cGMP signaling in animals.

C. elegans also displays the behavioral sequence of satiety; when satiated, they stop eating, stop moving, and often become quiescent (movie 1) (You et al. 2008). We called this behavior ‘satiety quiescence’ because (1) the quiescence is dependent on food quality; worms become quiescent on good food but not on poor food. (2) Decrease in food intake or decrease in food absorption in the intestine reduces quiescence. (3) The behavior is dependent on the animal’s past experience of starvation; worms that have experienced starvation show enhanced satiety quiescence after full refeeding compared to worms that have not (You et al. 2008). These results suggest the response to food is conserved in worms and mammals.

Which molecular mechanisms regulate worm satiety? We found that pkg-1 loss of function mutants show no quiescence, whereas the gain of function mutation shows excessive quiescence (You et al. 2008). This finding suggested a role for cGMP signaling in satiety quiescence, confirmed by the observation that the membrane guanylate cyclase DAF-11 and the cGMP-gated cation channel are necessary for satiety quiescence. Moreover, the most important neurons that regulate satiety quiescence in worms all express the cGMP-gated channel (TAX-2/TAX-4) and sense the worm’s environment and internal state (Komatsu et al. 1996). These neurons have critical roles in controlling body fat, determining body size and changing behaviors depending on environmental factors such as oxygen concentration (Fujiwara et al. 2002; Coates and de Bono 2002; Mak et al. 2006), temperature (Ramot et al. 2008), and light (Ward et al. 2008). This shows C. elegans also has a conserved circuit comprising neurons and the gut that senses nutrient states in order to regulate feeding. In addition this shows feeding is regulated by the same molecular mechanism of cGMP signaling in worms.

Interestingly, most mutants defective in satiety quiescence have darker intestines than wild type. A dark intestine usually correlates with more fat storage (McKay et al. 2003). In fact, some of the mutants that are defective in satiety quiescence, including daf-7, which lack a TGFβ, eat more (You et al. 2008) and store more fat than wild type (Kimura et al. 1997). Quiescence resulting from satiety suggests that worms don’t feed constantly, but rather regulate their feeding depending on nutritional status and environment. Quiescence-defective mutants could be defective in regulating feeding therefore feed more and accumulate more fat. Studies suggest that natriuretic peptide receptors, homologs of the guanylate cyclase DAF-11, have a role in storing and degrading fat through PKG in adipose tissue (Sengenes et al. 2000), suggesting another possibility of conserved link of the cGMP signaling pathways to regulation not only of feeding but also of fat metabolism in worms and mammals.

3. Conclusion: What can we learn from worms?

The dependence of feeding behavior on nutrient status, for example hunger or satiety, is likely to be conserved throughout the animal kingdom because it is directly related to animal survival. Our results show worms use similar signaling molecules such as insulin to sense nutrients and prompt the brain to respond to nutritional status, strongly suggesting that appetite control is conserved in worms both in molecular mechanisms and in behavior. Because worms don’t have distinct brain structures such as hypothalamus or a designated fat storage tissue, we cannot identify the worm physiology with that of mammals. As an example, worms don’t have a clear homolog of leptin which is released from adipose tissue to regulate feeding in mammals. However, the simple nervous system in combination with genetics will allow us to study the feeding circuitry and the molecules that connect the circuitry easily and fast. Moreover, even if some signaling molecules have diverged through evolution (such that worms don’t have leptin while human does), the overall feeding responses and majority of genes that are responsible for feeding are still well-conserved. As we described, worms alter their feeding motions depending on their nutritional status: they increase the feeding rate if they are hungry, and they don’t eat at all if they are satiated. And these changes in behavior are mediated by conserved genes. But feeding is not an isolated behavior. Hunger does not just make worms eat more; it makes them move more to seek food. The opposite is also true: satisfied worms never leave their food and often stop eating and become quiescent, mimicking post-prandial sleep. More interestingly, from the study of simple model systems such as worms or flies, we could see that one molecule can regulate multiple layers of responses to hunger or satiety. A muscarinic signal serves as a hunger signal to regulate not only feeding motions but also the physiology of the feeding muscles (You et al. 2006). cGMP signaling serves as a satiety signal, and it regulates not just feeding but also the animal’s entire behavioral response to food, including food seeking behavior (You et al. 2008). This multilayer control by an appetite control gene is also true in mammals. Leptin deficiency causes pleiotropic phenotypes such as obesity, diabetes and infertility including hypothalamic hypogonadism (Zhang et al. 1994; Montague et al. 1997). Therefore, understanding feeding and its regulation may help us to understand how animals develop, respond and behave so as to survive in a nutritionally unpredictable environment. Furthermore, studying feeding behaviors that are evolutionarily conserved and fundamental to survival in nature in the simple and genetically tractable systems will allow us, with relatively small cost and effort, to find more genetic components that regulate appetite control.

In 2008, WHO announced that at least 2.8 million people die each year as a result of being overweight or obese, and that about a billion of us (35% of world population) are obese. Yet despite significance of feeding in survival and the conservation in its molecular mechanisms throughout evolutionary tree, only 11 genes are discovered to regulate appetite in human (Mutch and Clement 2006). Therefore the knowledge of how genes regulate feeding behavior using a simple model organism will ultimately be applied to improve human health.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. J Kim for comments and reading. Leon Avery’s research is funded by research grants HL46154 and DK83593 from the National Institutes of Health and Young-Jai You’s research is supported by 09SDG2150070 from American Heart Association.

References

- Hetherington AW, Ranson SW. Hypothalamic lesions and adiposity in the rat. Anat Rec. 1940;78:149–172. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz MW, Woods SC, Porte D, Jr, Seeley RJ, Baskin DG. Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature. 2000;404:661–671. doi: 10.1038/35007534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KG, Bloom SR. Gut hormones and the regulation of energy homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444:854–859. doi: 10.1038/nature05484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz GJ, Fu J, Astarita G, Li X, Gaetani S, Campolongo P, Cuomo V, Piomelli D. The lipid messenger OEA links dietary fat intake to satiety. Cell Metab. 2008;8:281–288. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J, Young RC, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin elicits satiety in rats with open gastric fistulas. Nature. 1973a;245:323–325. doi: 10.1038/245323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J, Young RC, Smith GP. Cholecystokinin decreases food intake in rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1973b;84:488–495. doi: 10.1037/h0034870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372:425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague CT, Farooqi IS, Whitehead JP, Soos MA, Rau H, Wareham NJ, Sewter CP, Digby JE, Mohammed SN, Hurst JA, et al. Congenital leptin deficiency is associated with severe early-onset obesity in humans. Nature. 1997;387:903–908. doi: 10.1038/43185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi IS, Matarese G, Lord GM, Keogh JM, Lawrence E, Agwu C, Sanna V, Jebb SA, Perna F, Fontana S, et al. Beneficial effects of leptin on obesity, T cell hyporesponsiveness, and neuroendocrine/metabolic dysfunction of human congenital leptin deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1093–1103. doi: 10.1172/JCI15693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist JK, Elias CF, Saper CB. From lesions to leptin: hypothalamic control of food intake and body weight. Neuron. 1999;22:221–232. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa A, Inui A, Kaga T, Yuzuriha H, Nagata T, Ueno N, Makino S, Fujimiya M, Niijima A, Fujino MA, et al. Ghrelin is an appetite-stimulatory signal from stomach with structural resemblance to motilin. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:337–345. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inui A. Ghrelin: an orexigenic and somatotrophic signal from the stomach. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:551–560. doi: 10.1038/35086018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran TH, Kinzig KP. Gastrointestinal satiety signals II. Cholecystokinin. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;286:G183–188. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00434.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis HM, Horvitz HR. Genetic control of programmed cell death in the nematode C. elegans. Cell. 1986;44:817–829. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz HR, Shaham S, Hengartner MO. The genetics of programmed cell death in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1994;59:377–385. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1994.059.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi K, Chang FY, Watts JL, Fraser AG, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Ruvkun G. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans fat regulatory genes. Nature. 2003;421:268–272. doi: 10.1038/nature01279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashrafi K. Obesity and the regulation of fat metabolism. WormBook; 2007. pp. 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura KD, Tissenbaum HA, Liu Y, Ruvkun G. daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 1997;277:942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apfeld J, O’Connor G, McDonagh T, DiStefano PS, Curtis R. The AMP-activated protein kinase AAK-2 links energy levels and insulin-like signals to lifespan in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3004–3009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gilst MR, Hadjivassiliou H, Jolly A, Yamamoto KR. Nuclear hormone receptor NHR-49 controls fat consumption and fatty acid composition in C. elegans. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze JY, Victor M, Loer C, Shi Y, Ruvkun G. Food and metabolic signalling defects in a Caenorhabditis elegans serotonin-synthesis mutant. Nature. 2000;403:560–564. doi: 10.1038/35000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase DL, Pepper JS, Koelle MR. Mechanism of extrasynaptic dopamine signaling in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nn1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suo S, Culotti JG, Van Tol HH. Dopamine counteracts octopamine signalling in a neural circuit mediating food response in C. elegans. EMBO J. 2009;28:2437–2448. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezcurra M, Tanizawa Y, Swoboda P, Schafer WR. Food sensitizes C. elegans avoidance behaviours through acute dopamine signalling. EMBO J. 2011;30:1110–1122. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AH, Jr, Riker WF., Jr Acetylcholine Release at the Neuromuscular Junction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1963;142:200–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JF, Silver A. The spontaneous release of acetylcholine from the denervated hemidiaphragm of the rat. J Physiol. 1963;165:117–129. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud RM, Finer-Moore J. Acetylcholine receptor structure, function, and evolution. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1985;1:317–351. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.01.110185.001533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wess J. Molecular basis of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1993;14:308–313. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90049-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance WT, Lints CE. Eating following cholinergic stimulation of the hypothalamus. Physiological Psychology. 1977;5:440–444. [Google Scholar]

- Yamada M, Miyakawa T, Duttaroy A, Yamanaka A, Moriguchi T, Makita R, Ogawa M, Chou CJ, Xia B, Crawley JN, et al. Mice lacking the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor are hypophagic and lean. Nature. 2001;410:207–212. doi: 10.1038/35065604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gautam D, Jeon J, Starost MF, Han SJ, Hamdan FF, Cui Y, Parlow AF, Gavrilova O, Szalayova I, Mezey E, et al. Neuronal M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors are essential for somatotroph proliferation and normal somatic growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6398–6403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900977106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston-Green K, Huang XF, Lian J, Deng C. Effects of olanzapine on muscarinic M3 receptor binding density in the brain relates to weight gain, plasma insulin and metabolic hormone levels. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MB, Earle KR. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding with truncal vagotomy: any increased weight loss? Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2522–2525. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1580-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral JG, Gortz L, Hermansson G, Wallin GS. Gastroplasty for obesity: long-term weight loss improved by vagotomy. World J Surg. 1993;17:75–78. doi: 10.1007/BF01655710. discussion 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You YJ, Kim J, Cobb M, Avery L. Starvation activates MAP kinase through the muscarinic acetylcholine pathway in Caenorhabditis elegans pharynx. Cell Metab. 2006;3:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne KA, Robichon A, Burgess E, Butland S, Shaw RA, Coulthard A, Pereira HS, Greenspan RJ, Sokolowski MB. Natural behavior polymorphism due to a cGMP-dependent protein kinase of Drosophila. Science. 1997;277:834–836. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5327.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shahar Y, Robichon A, Sokolowski MB, Robinson GE. Influence of gene action across different time scales on behavior. Science. 2002;296:741–744. doi: 10.1126/science.1069911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara M, Sengupta P, McIntire SL. Regulation of body size and behavioral state of C. elegans by sensory perception and the EGL-4 cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Neuron. 2002;36:1091–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizen DM, Zimmerman JE, Maycock MH, Ta UD, You YJ, Sundaram MV, Pack AI. Lethargus is a Caenorhabditis elegans sleep-like state. Nature. 2008;451:569–572. doi: 10.1038/nature06535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino MA, Lin JE, Snook AE, Li P, Kim GW, Marszalowicz G, Magee MS, Hyslop T, Schulz S, Waldman SA. A uroguanylin-GUCY2C endocrine axis regulates feeding in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3578–3588. doi: 10.1172/JCI57925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You YJ, Kim J, Raizen DM, Avery L. Insulin, cGMP, and TGF-beta signals regulate food intake and quiescence in C. elegans: a model for satiety. Cell Metab. 2008;7:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu H, Mori I, Rhee JS, Akaike N, Ohshima Y. Mutations in a cyclic nucleotide-gated channel lead to abnormal thermosensation and chemosensation in C. elegans. Neuron. 1996;17:707–718. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80202-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates JC, de Bono M. Antagonistic pathways in neurons exposed to body fluid regulate social feeding in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2002;419:925–929. doi: 10.1038/nature01170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak HY, Nelson LS, Basson M, Johnson CD, Ruvkun G. Polygenic control of Caenorhabditis elegans fat storage. Nat Genet. 2006;38:363–368. doi: 10.1038/ng1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramot D, MacInnis BL, Lee HC, Goodman MB. Thermotaxis is a robust mechanism for thermoregulation in Caenorhabditis elegans nematodes. J Neurosci. 2008;28:12546–12557. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2857-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A, Liu J, Feng Z, Xu XZ. Light-sensitive neurons and channels mediate phototaxis in C. elegans. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:916–922. doi: 10.1038/nn.2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay RM, McKay JP, Avery L, Graff JM. C elegans: a model for exploring the genetics of fat storage. Dev Cell. 2003;4:131–142. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00411-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengenes C, Berlan M, De Glisezinski I, Lafontan M, Galitzky J. Natriuretic peptides: a new lipolytic pathway in human adipocytes. Faseb J. 2000;14:1345–1351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutch DM, Clement K. Unraveling the genetics of human obesity. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]