Abstract

The structure of mollenyne A, acytotoxic nitrogenous halogenated long-chain carboxamide from the sponge Spirastrella mollis, was elucidated by integrated spectroscopic analysis, including CD, and chemical conversion.

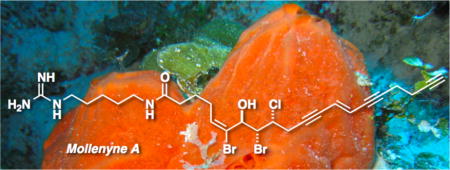

Brominated lipids commonly occur in several genera of marine sponges including Petrosia, Xestospongia and Oceanapia.1 Unlike the Rhodophyta (red algae), which are replete with halogenated terpenes and lipids containing myriad combinations of Br, Cl and sometimes I, Porifera (sponges) – suprisingly – rarely contain compounds with both Br and Cl. We describe here mollenyne A (1) from the sponge Spirastrella mollis Verrill, 1907,2 collected from the Bahamas (Plana Cays). Mollenyne A (1) is a chiral tri-halogenated cytotoxic C20 carboxamide, embodying three units: a triyne-ene terminus, an allylic alcohol flanked by halogenated carbons, and homoagmatine (decarboxyhomoarginine).3

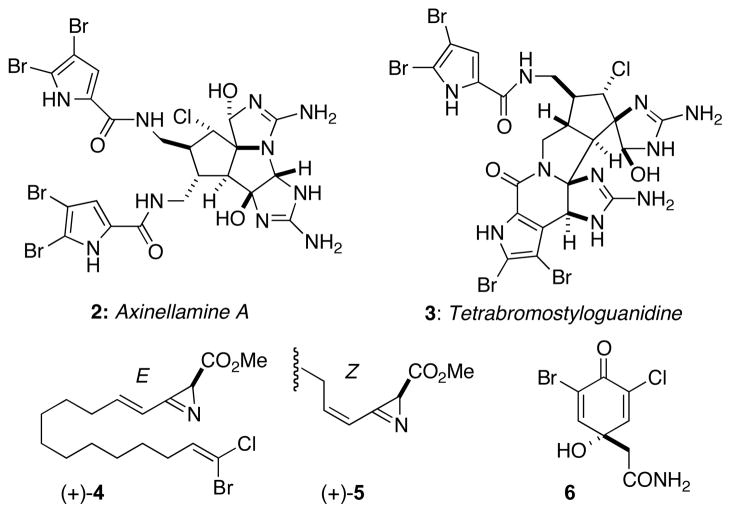

The only other bromochloro natural products from sponges are axinellamine A4 (2) from Axinella sp. and tetrabromostyloguanidine (3)5 from Stylissa caribica (Figure 1), long-chain terminal vinyl bromochloro azirines (4E-4 and 4Z-5)6 from Dysidea fragilis, and halogenated cyclohexenones from Aplysina cavernicola (e.g. 3-bromo-5-chloroverongiaquinol, 6),7 but none resemble 1. Screening of crude extracts from a collection of Bahamian sponges and tunicates (n = 180) in assays with cultured cancer cells (human colon tumor, HCT-116) identified a highly cytotoxic extract from the red encrusting sponge Spirastrella mollis (IC50 ≤ 0.1 μg/mL). Further purification of the CH2Cl2 partition from S. mollis by C18 flash chromatography and reversed phase HPLC gave a new halogenated lipid, mollenyne A (1).

Figure 1.

Mollenyne A (1) from Spirastrella mollis.

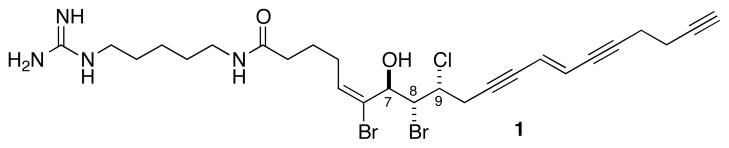

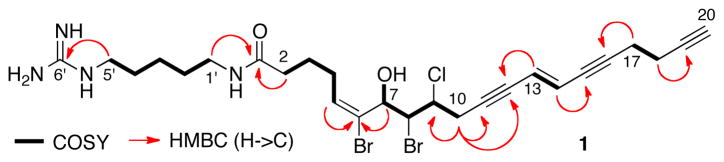

HRESIMS analysis of 1 revealed the molecular formula of C26H36O2N4Br2Cl (m/z 629.0888 [M+H]+) with 10 degrees of unsaturation and six exchangable hydrogens (LRESIMS in CD3OD, m/z at 635 [M+H]+). Interpretation of one and two dimensional NMR experiments allowed the assignment of five substructures (A–E, Figure 3 and Table 1). Substructure A contained a 1H spin system of three contiguous methylene groups H2 through H4 (δ 2.23, t, J = 7.4 Hz, δ 1.79, and δ 2.23, respectively) and terminated with a vinyl proton H5 (δ 6.10, t, J = 7.7 Hz).

Figure 3.

Substructures of 1 (A–E) assigned from 2D NMR

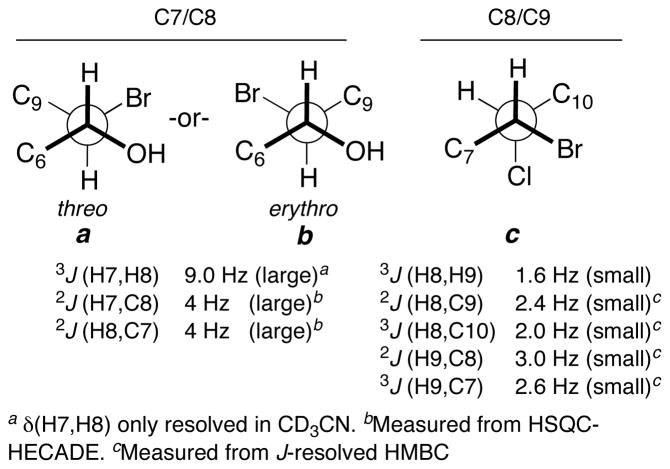

Table 1.

1H and 13C NMR data for 1 (CD3OD, 600 MHz). See Supporting Information for NMR data in CD3CN.

| #. | δH, m (J in Hz) | δCa | DQF-COSY | HMBCb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 175.6 | C | |||

| 2 | 2.23, t (7.4) | 36.4 | CH2 | 3 | 1, 3, 4 |

| 3 | 1.79 (m) | 26.3 | CH2 | 2, 4 | 1, 2, 4, 5 |

| 4 | 2.23 (m) | 30.3 | CH2 | 3, 5 | 2, 3, 5, 6 |

| 5 | 6.10, t (7.7) | 137.3 | CH | 4 | 3, 4, 6, 7 |

| 6 | 128.5 | C | |||

| 7 | 4.73, d (9.7) | 70.8 | CH | 8 | 5, 6, 8, 9 |

| 8 | 4.57, md | 59.3c | CH | 7 | 6, 7, 9, 10 |

| 9 | 4.57, md | 59.4c | CH | 10 | 7, 8, 10, 11 |

| 10 | 2.97, m | 29.6 | CH2 | 9, 13 | 8, 9, 11, 12, 13 |

| 11 | 89.9 | C | |||

| 12 | 82.6 | C | |||

| 13 | 5.91, dt (16.1, 1.9) | 122.6 | CH | 10, 14 | 14 |

| 14 | 5.97, dt (16.1, 2.0) | 120.7 | CH | 13, 17 | 13 |

| 15 | 80.4 | C | |||

| 16 | 94.6 | C | |||

| 17 | 2.54, td (7.2, 2.0) | 20.4 | CH2 | 14, 18 | 15, 16, 18, 19 |

| 18 | 2.39, td (7.2, 2.6) | 19.2 | CH2 | 17, 20 | 16, 17, 19, 20 |

| 19 | 83.3 | C | |||

| 20 | 2.31, t (2.6) | 70.5 | CH | 18 | 18 |

| 1′ | 3.18, t (7.2) | 40.1 | CH2 | 2′ | 1, 2′, 3′ |

| 2′ | 1.54, p (7.2) | 30.1 | CH2 | 1′, 3′ | 1′, 3′, 4′ |

| 3′ | 1.38, p (7.2) | 24.9 | CH2 | 2′, 4′ | 1′, 2′, 4′, 5′ |

| 4′ | 1.61, p (7.2) | 29.4 | CH2 | 3′, 5′ | 2′, 3′, 5′ |

| 5′ | 3.16, t (7.2) | 42.4 | CH2 | 4′ | 3′, 4′, 6′ |

| 6′ | 158.6 | C |

Inferred from DEPT and HSQC, 600 MHz.

HMBC correlations, optimized for 8 Hz. Correlations are from H→C.

May be interchanged.

J obscured by overlapping multiplets.

C5 (δ 137.3) was connected to a quaternary sp2 carbon C6 (δ 128.5) by an HMBC cross peak from H5 to C6. COSY and TOCSY correlations showed the oxygenated methine H7 (δ 4.73, d, J = 9.7 Hz) was coupled to methine H8 (δ 4.57, m), and H9 (δ 4.57, m) was coupled to H10 (δ, 2.97, m) leading to substructure B.

Substructure C of 1 is a trans disubstituted alkene (δ 5.91, dt, J = 16.1, 1.9 Hz, H13; 5.97, dt, J = 16.1, 2.0 Hz, H14). Substructure D contained the C19-C20 acetylene terminus (δH 2.31, t, J = 2.6 Hz, H20; δC 70.5, C20, CH; 94.6, Cq, C19) linked to a 1,2-disubstituted ethane, H17 (δ 2.54, td, J = 7.2, 2.0 Hz) and H18 (δ 2.39, td, J = 7.2, 2.6 Hz). The final substructure E was assigned as a 1,5-diamine unit.

Substructures A–E were assembled by further analysis of HMBC spectra (Figure 5.5). A and E were connected through an amide carbonyl group (δ 175.6, C1) which showed HMBC correlations to both H2 and H1′. Hydroxymethine H7 showed a correlation to C5 which established the link between substructures A and B. The C5–C6 double bond was assigned the E geometry based on NOESY correlation between H4 and H7. Both H10 and H13 showed correlations to sp carbons C11 (δ 89.9) and C12 (δ 82.6).

Substructure D was attached to C by a third C-C triple bond [C15 (δ 80.4) and C16 (δ 94.6)]. The left fragment N-terminal fragment of 1 was identified as a guanidine group based on the balance of the molecular formula and HMBC correlation from H5′ to C6′ with a characteristic C=N chemical shift (δ 158.6).

Placement of the halogens (two Br and one Cl) was supported by NMR and chemical conversion.8 A vinyl bromide was favored over a vinyl chloride based on comparison of 13C chemical shifts with known synthetic compounds.9 The quaternary sp2 carbon bearing a Br (~δ 125 ppm) is typically observed upfield of the protonated sp2 carbon (~ δ 133 ppm) in trisubstituted vinyl bromides (‘heavy atom’ effect). In vinyl chlorides, the opposite trend is observed; the quaternary sp2 carbon (~ δ 135 ppm) is observed downfield of the protonated sp2 carbon (~ δ 125 ppm). Based on 13C chemical shift and chemical transformation (see below) the remaining Br and Cl were placed at C8 and C9, respectively.

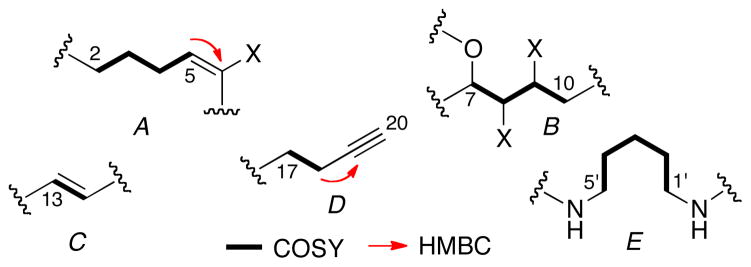

To assign the relative configuration of mollenyne A (1), we turned to J-based configurational analysis (JBCA), established by Murata and coworkers for hydroxylated polyketides.10 The stereotriad of 1 resembles those found in chlorosulfolipids11 isolated from Adriatic shellfish,12 freshwater algae13 and marine cyanobacteria.14 Recently, the Carreira group completed a meticulous investigation of the homo- and hetero-nuclear two- and three-bond coupling constants in a series of chlorosulfolipid models15 and demonstrated that subtle differences should be considered when analyzing spin systems of polychlorinated compounds compared to those of polyhydroxylated ketides. The former more reliable basis sets were used as a starting point for JBCA analysis of 1.

The C8-C9 threo configuration was assigned by JBCA in a straightforward manner (Figure 5, conformer c). H8 and H9 were oriented gauche based on a small vicinal homonuclear coupling (J = 1.6 Hz), however the low magnitude lead to inefficient magnetization transfer and we were unable to observe 2JHC and 3JHC coupling constants by HETLOC or HSQC-HECADE experiments. Consequently, we turned to J-resolved HMBC that revealed the magnitudes of all heteronuclear couplings were small (Figure 5). The vicinal Br and Cl were oriented anti to H9 and H8, respectively, and C7 and C10 were assigned gauche to H9 and H8, respectively. H7 and H8 were oriented anti based on large H-H vicinal coupling (J = 9.0 Hz), and HSQC-HECADE revealed that both 2JHC H7-C8 and H8-C7 have large couplings. These data are accommodated by either diastereomer threo a or erythro b (Figure 5), an ambiguity that was resolved by chemical conversion as follows.

Figure 5.

3JHH, 2JHC, and 3JHC coupling constants for C7–C9 of 1 (600 MHz, CD3CN).

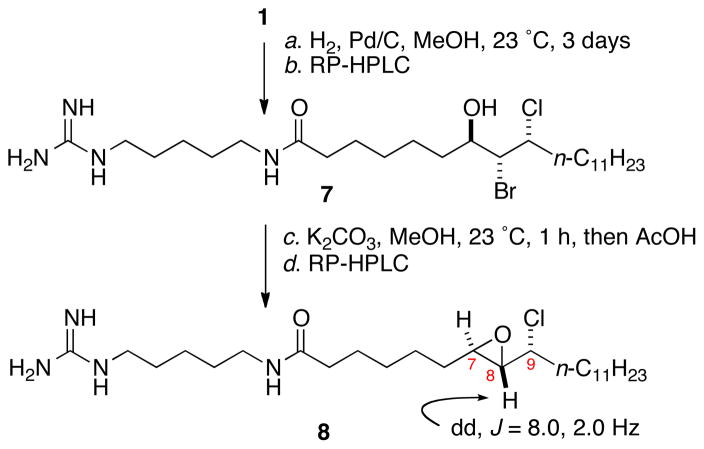

Mollenyne A (1) underwent hydrogenation (H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 3 days, Scheme 1), with concomitant hydrogenolysis of the vinyl bromide to give 7. Exposure of the product 7 to base (K2CO3, MeOH) gave epoxide 816 after neutralization (AcOH), and HPLC purification. The vicinal H7-H8 coupling constant (J = 2 Hz) confirmed a trans epoxide. Accounting for inversion at C8 during epoxide ring closure by SN2 substitution, the relative configuration of the C7-C8 stereocenters in 1 was revealed as erythro b (Figure 5).

Scheme 1.

Conversion of 1 to chloroepoxide 8.

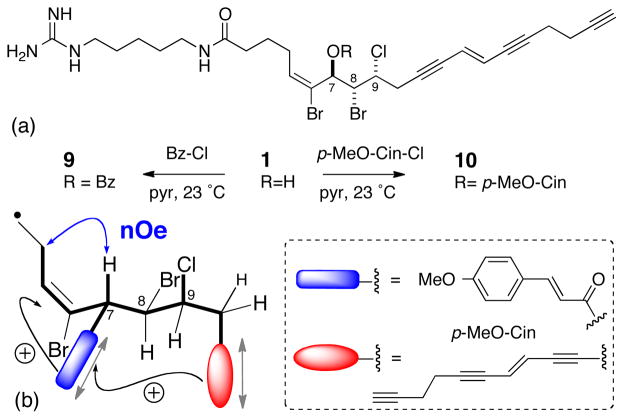

Assignment of the carbinol center C7 and completion of the absolute stereostructure of 1 were achieved by conversion of the latter to chromophoric derivatives and application of the exciton chirality CD (ECCD) method. Nakanishi reported17 that cyclic and acyclic allylic alcohols can be assigned by simple interpretation of ECCD of their corresponding benzoate derivatives; the latter arises from exciton coupling between π–π* transitions of the O-benzoate and C=C double bond.

In principle, this analysis is applicable to an O-benzoyl-derivative of 1, however, additional contributions were anticipated from long-range EC with a second chromophore: the C11-C16 conjugated yne-ene-yne.

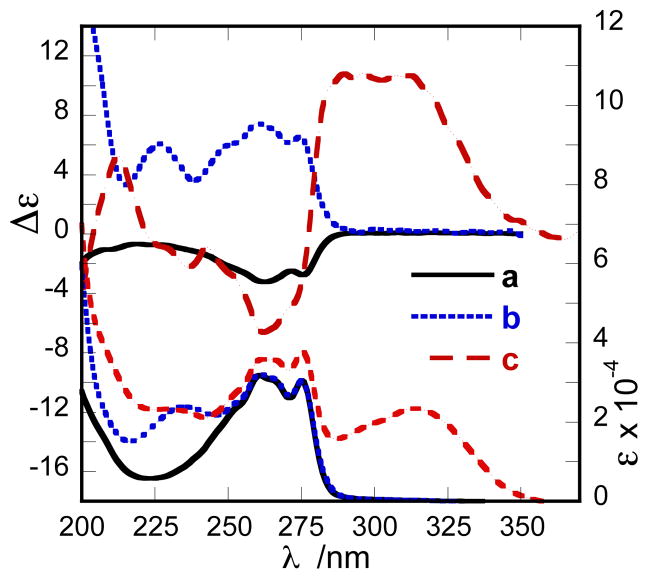

Mollenyne A (1) was benzoylated under standard conditions (Bz-Cl, pyridine), and the CD spectrum of the HPLC-purified benzoate ester 9 was acquired in MeOH (Scheme 2 and Figure 6). Two positive Cotton effects (CEs) associated with the benzoate chromophore [λ 227 nm (Δε +6.1)], and yne-ene-yne chromophore18 [λ 260 nm (Δε +7.5), 275 nm (Δε +6.5)] were observed, and ascribed to separate EC effects. The positive CE at λ 227 nm was assigned as the high-energy component of the exciton couplet arising from positive helicity between the double bond (λ ~190 nm) and the benzoate chromophore (λ = 227 nm)(Scheme 2). The negative CE expected from the C=C π–π* contribution, but was obscured by solvent (MeOH, cutoff ~200 nm). A positive split CE between the yne-ene-yne chromophore and the benzoate was assigned to a positive helicity, however, the expected negative CE at λ = 227 nm is canceled by the positive component of the allylic benzoate EC couplet.

Scheme 2.

Conversion of 1 to the corresponding benzoate (9) and p-methoxycinnamate (10) esters, and the major conformer accounting for the observed ECCD spectra.

Figure 6.

UV (lower) and CD (upper) spectra (MeOH, 23 °C) for (a) 1, (b) 9, and (c) 10. Δε for 1 and 9 were normalized to an ene–yne–ene chromophore18 and 10 was normalized to p-methoxycinnamate.19

In order to remove the ambiguity and ‘red-shift’ the ECCD interactions, mollenyne A (1) was derivatized with para–methoxycinnamoyl chloride to give 10 (Scheme 2). Gratifyingly, a clear bisignate CE emerged [Figure 6, λ 262 nm (Δε −6.6); ~296 nm (Δε +10.8)] that was assigned to a positive helicity of the allylic O-cinnamate ester. Consequently, 10 and 1 have the 7S,8R,9R configuration. The latter assignment was verified by calculation of mimimized structures of a truncated benzoate model of 9 (C4 to C12, Spartan, MMFF). The lowest energy conformer (65% of Boltzmann-weighted population) of 1 was consistent with the solution structure predicted from NMR and CD studies and fully supports the 7S,8R,9R assignment.

Few compounds have been reported from the genus Spirastrella;20 including cytotoxic macrolides, spirastrellolides A-G,20a–c sphingosine sulfates20d and halogenated hydrocarbons.20e An account of the biosynthesis of 1, the first natural products reported from S. mollis, must explain two uncommon features; the rare homoagmatine (1-amino-5-N-guanidino) group21 which likely arises from decarboxylation of arginine,3 and the chlorodibromohydrin in the C20 carboxamide segment that is without precedent among sponge metabolites. Compound 1 exhibited significant cytotoxicity against human colon tumor cells (HCT-116; IC50 = 1.3 μg/mL; etoposide = 0.55 μg/mL).

In conclusion an unusual optically active chlorodibromohydrin, mollenyne A (1) was obtained from the marine sponge Spirastrella mollis, and its complete stereostructure solved by an integrated approach employing NMR, MS, CD and chemical synthesis.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Bromochloro-natural products from sponges

Figure 4.

Assembly of substructures A–E of 1 through COSY and HMBC correlations.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Zea (INVAMAR, University of Columbia) for identification of the sponge, J. Pawlik (University of North Carolina, Wilmington) and the crew of the RV Seward Johnson for logistics of sponge collection, Y. Su for HRMS measurements, T. Handel, A. Jansma, and X. Huang (all UCSD) for assistance with NMR experiments, and D. Dalisay for assistance with biological assays. We also thank an anonymous reviewer for the reference to 37Cl/35Cl isotope effects on 13C NMR (ref. 8). The 500 MHz NMR spectrometers were purchased with a grant from the NSF (CRIF, CHE0741968). BIM is grateful for a Ruth L. Kirstein National Research Service Award NIH/NCI (T32 CA009523). This work was supported by the NIH (AI039987, CA122256).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available. Experimental procedures and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) Gribble GW. J Chem Ed. 2004;81:1441. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gribble GW. Acc Chem Res. 1998;31:141. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hartung J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 1999;38:1209. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990503)38:9<1209::AID-ANIE1209>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.S. mollis may be conspecific with S. hartmani Boury-Esnault N, Klautau M, Bézac C, Wulff J, Solé-Cava AM. J Mar Biol Ass UK. 1999;79:39.

- 3.Ramakrishna S, Adiga PR. Phytochemistry. 1973;12:2691. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Urban S, Leone P, de A, Carroll AR, Fechner GA, Smith J, Hooper JNA, Quinn RJ. J Org Chem. 1999;64:731. doi: 10.1021/jo981034g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grube A, Köck M. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2007;46:2320. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Skepper CK, Molinski TF. J Org Chem. 2008;73:2592. doi: 10.1021/jo702435s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Pietra F. Helv Chim Acta. 1984;67:1484. [Google Scholar]

- 8.In favorable cases, Cl atoms can also be located upon observation of 35Cl,37Cl isotope shifts in 13C NMR. Sergeyev NM, Sandor P, Sergeyeva ND, Raynes W. J Magn Reson Ser A. 1995;115:174. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1998.1682.

- 9.For synthesis of naturally occurring vinyl bromides and chlorides, see: Trost BM, Pinkerton AB. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:7376. doi: 10.1021/ja011426w.Lütjens H, Wahl G, Möller F, Knochel P, Sundermeyer J. Organometallics. 1997;16:5869.Hodgson DM, Arif T. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:6500. doi: 10.1021/ja8076999.

- 10.Matsumori N, Kaneno D, Murata M, Nakamura H, Tachibana K. J Org Chem. 1999;64:866. doi: 10.1021/jo981810k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bedke DK, Vanderwal CD. Nat Prod Rep. 2010;28:15. doi: 10.1039/c0np00044b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.(a) Ciminiello P, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Di Rosa M, Ianaro A, Poletti A. J Org Chem. 2001;66:578. doi: 10.1021/jo001437s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ciminiello P, Dell’Aversano C, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Magno S, Di Rosa M, Ianaro A, Poletti R. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13114. doi: 10.1021/ja0207347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ciminiello P, Dell’Aversano C, Fattorusso E, Forino M, Magno S, Di Meglio P, Ianaro A, Poletti R. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:7093. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Mercer EI, Davies CL. Phytochemistry. 1974;13:1607. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mercer EI, Davies CL. Phytochemistry. 1975;14:1545. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mercer EI, Davies CL. Phytochemistry. 1979;18:457. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Chen JL, Proteau PJ, Roberts MA, Gerwick WH, Slate DL, Lee RH. J Nat Prod. 1994;57:524. doi: 10.1021/np50106a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bedke DK, Shibuya GM, Pereira AR, Gerwick WH, Vanderwal CD. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2542. doi: 10.1021/ja910809c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nilewski C, Geisser RW, Ebert MO, Carreira EM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:15866. doi: 10.1021/ja906461h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HRESIMS m/z 487.3776 [M+H]+ (calcd for C26H52ClN4O2 487.3773). Sequential elimination of two molecules of HBr upon conversion of 1 to 8 confirmed the location of the halogens in 1.

- 17.(a) Harada N, Iwabuchi J, Yokota Y, Uda H, Nakanishi K. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:5590. [Google Scholar]; (b) Gonnella NC, Nakanishi K, Martin VS, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1982;104:3775. [Google Scholar]

- 18.CD and UV spectra were normalized using literature ε values for an ene–yne–ene chromophore. λmax 261 nm (ε 32,000), 276 nm (ε 30,500). Crombie L, Jacklin AG. J Chem Soc. 1957:1632.

- 19.λmax 311 nm (ε 24,000). Wiesler WT, Nakanishi K. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:5574.

- 20.(a) Williams DE, Keyzers RA, Warabi K, Desjardine K, Riffell JL, Roberge M, Andersen RJ. J Org Chem. 2007;72:9842. doi: 10.1021/jo7018174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Williams DE, Lapawa M, Feng X, Tarling T, Roberge M, Andersen RJ. Org Lett. 2004;6:2607. doi: 10.1021/ol0490983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Williams DE, Roberge M, Van Soest R, Andersen RJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:5296. doi: 10.1021/ja0348602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Alam N, Wang W, Hong J, Lee CO, Im KS, Jung JH. J Nat Prod. 2002;65:944. doi: 10.1021/np010312v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Martín MJ, Berrué F, Amade P, Fernández R, Francesch A, Reyes F, Cuevas C. J Nat Prod. 2005;68:1554. doi: 10.1021/np050247f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Homoagmatine has also been observed in the sponge metabolite clavatadine from a species of Suberea. Buchanan MS, Carroll AR, Wessling D, Jobling M, Avery VM, Davis RA, Feng Y, Hooper JN, Quinn RJ. J Nat Prod. 2009;72:973. doi: 10.1021/np8008013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.