Abstract

Numerous marine-derived pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids (PIAs), ostensibly derived from the simple precursor oroidin, 1a, have been reported and have garnered intense synthetic interest due to their complex structures and in some cases biological activity; however very little is known regarding their biosynthesis. We describe a concise synthesis of 7-15N-oroidin (1d) from urocanic acid and a direct method for measurement of 15N incorporation by pulse labeling and analysis by 1D 1H-15N HSQC NMR and FTMS. Using a mock pulse labeling experiment, we estimate the limit of detection (LOD) for incorporation of newly biosynthesized PIA by 1D 1H-15N HSQC to be 0.96 μg equivalent of 15N oroidin (2.4 nmole) in a background of 1500 μg unlabeled oroidin (about 1 part per 1600). 7-15N-Oroidin will find utility in biosynthetic feeding experiments with live sponges to provide direct information to clarify the pathways leading to more complex pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids.

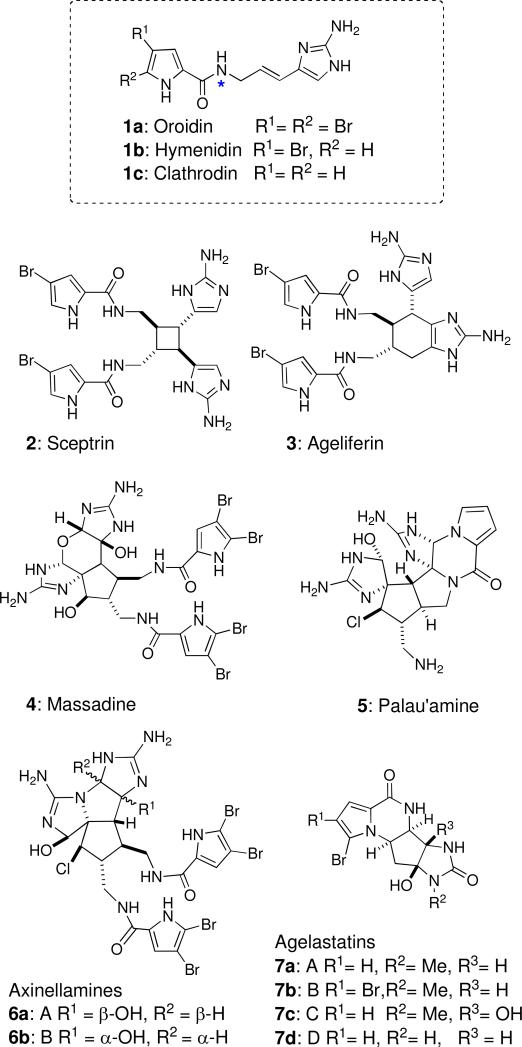

The polycyclic pyrrole-imidazole alkaloid (PIA) family has received much attention recently from the synthetic organic communityi because of their challenging molecular structure, dense functionality and potential biological activity. All are believed to derive from a simple common sponge metabolite; most likely oroidin (1a) or its analogs hymenidin (1b) and clathrodin (1c), the structures of which differ only in bromine content.ii Representative of the members of this family are the dimeric PIAs sceptrin (2),iii ageliferin (3),iv massadine (4),v palau'amine (5)vi and axinellamines A and B (6a-b),vii and higher-order tetrameric PIAs.viii In addition, compact monomeric polycyclic PIAs, such as agelastatins A,ix B,x C and Dxi (7a-d) and dibromophakellinxii appear to be derived from oxidative intramolecular cyclizations of oroidin (1a) or hymenidin (1b). PIAs are of contemporary interest due to their potent biological activity and intriguing biosyntheses. For example, (–)-agelastatin A (7a), an antitumor PIAx is 1.5-16 times more active than cisplatin against a range of tumor cell lines, and potently inhibits osteopontin, an adhesion glycoprotein transcriptionally regulated by the Wnt β-catenin pathway and implicated in tumor progression, dissemination, and metastases.xiii

The widely accepted hypothesis for biosynthesis of dimeric and tetrameric PIAs, involves dimerization of oroidin (1a) followed by consecutive oxidative transformations leading to more densely functionalized, polycyclic alkaloids.viii In 1982, Büchi reported a ‘biomimetic’ synthesis of the simple PIA, racemic dibromophakellin, by oxidative cyclization of 9,10-dihydrooroidin.xiv The structure of sceptrin (2) is highly suggestive of a formal [2+2] cycloaddition of two molecules of hymenidin (1b) to 2; however, despite many attempts, Faulkner, Clardy and co-workers were unable to achieve photodimerization of 1b to 2,iii suggesting that an alternative non-concerted mechanism may be responsible for the biosynthesis. Recent speculation on the order of biosynthesis of 2 and 3 revolves around ionic mechanisms of ring-expansion, supported by the demonstrated conversion of 2 to 3 under thermal conditions, if,xv,xvi or a ring-contraction pathway from an ageliferin-type dimer generated by a Diels Alder type cycloaddition of two molecules of hymenidin (1b).ii For example, one speculative hypothesis invokes a cycloaddition in the biosynthesis of palau'aminevib and axinellamine, followed by a stepwise electrophilic chlorination and ring contraction. Remarkably, none of the above hypotheses have been tested experimentally in live sponges.

We describe here a synthesis of 15N-labeled oroidin (1d) and optimization of conditions for detection of 15N-incorporation by microscale FTMS and 1H-15N HSQC using a ‘mock’ pulse-labeling experiment with 1d and natural oroidin (1a). We estimate the limits of detection of these methods and determine their suitability for use in field incorporation for biosynthetic studies of complex PIAs with living sponges. This information can be used to answer biosynthetic questions of the biosynthesis of PIAs by sponges in the genera Agelas, Stylissa and Ptilocaulis.

Results and Discussion

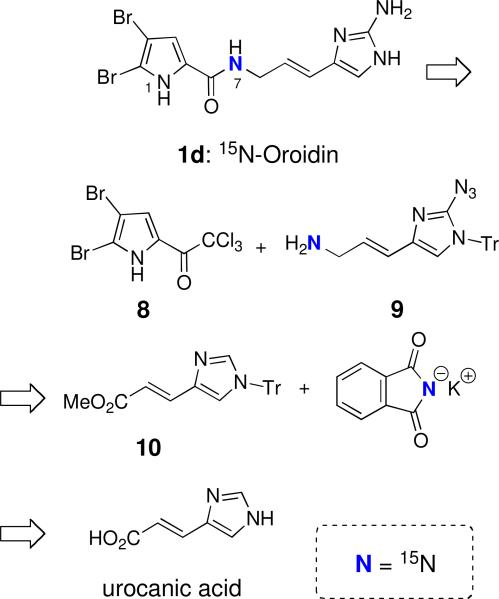

Several syntheses of oroidin have been described in the literature and the synthetic approaches utilized can be classified into two categories.xvii The first involves synthesis of the required 2-aminoimidazole ring by condensation of a guanidine derivativexviii or cyanamidexix with an α-haloketone. An alternative strategy involves amination of an imidazole ring via azido or diazonium transfer reagents.xx We elected the latter strategy for brevity and the utility of the commercially available, starting material urocanic acid, as demonstrated by Lovely.io,xxi This strategy enabled a late-stage introduction of the 15N-label which is ideal for cost considerations (Scheme 1). Disconnection of the amide bond leads to the known 4,5-dibromo-2-trichloroacetylpyrrole 8,xxib,c readily synthesized from commercially available 2-trichloroacetylpyrrole, and the 15N-labeled allylic amine 9 which could be obtained by a lithiation/azidation sequence at the 2-position of the N-protected urocanic acid ester 10. The 15N label would be introduced towards the end of the overall sequence by Gabriel synthesis employing the potassium salt of commercially available 15N-phthalimide and an activated derivative of the alcohol, that in turn, could be obtained by reduction of the carbomethoxy group of ester 10.

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of 7-15N-oroidin (1d) from urocanic acid.

Fisher esterification of urocanic acid with methanol (Scheme 2) and subsequent protection gave the known N-trityl imidazole derivative 10. xxii Reduction of ester 10 (DIBAL-H) afforded the corresponding alcohol 11 in excellent yield. Initial attempts to execute a direct azidation of alcohol 11 at the 2-imidazole position with the unprotected alcohol using known procedures (n-BuLi/ TsN3),xxc-e gave none of the desired azido product. Instead, the product obtained was tentatively assigned the structure of a triazene-imidazole derivative based on 1H NMR and mass spectrometric analysis.xxiii When the TBS protected imidazole 12 was subjected to the previously employed conditions for azido-transfer, azide 13 was obtained in excellent yield. Deprotection of silyl ether 13 with TBAF afforded alcohol 14, which was then subjected to mesylation (MsCl, Et3N). Without purification, the mesylate was treated with the potassium salt of 15N-phthalimide (>98% atom 15N) to provide the 15N-labeled pthalimide 15. Cleavage of phthalimide 15 with NH2NH2 furnished the 15N-allylic amine 9 which was acylated with 4,5-dibromo-2-trichloroacetylpyrrole (8) to provide 15N-pyrrolecarboxamide 16 in good overall yield. Removal of the trityl group from 16 with anhydrous methanolic HCl, generated in situ from acetyl chloride and MeOH, afforded the corresponding 2-azido imidazolexxc that was hydrogenated in the presence of Lindlar's catalyst to provide 7-15N-oroidin (1d, >98% atom 15N).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 15N-labeled oroidin.a

aReagents and conditions: (a) AcCl, MeOH, reflux, quant.; (b) TrCl, Et3N, DMF; (c) DIBAL-H, THF; (d) TBSCl, imidazole, 74% for 3 steps; (e) n-BuLi, TsN3, THF, 94%; (f) TBAF, THF, 82%; (g) MsCl, Et3N, THF; (h) potassium phthalimide-15N, DMF, 42% for 2 steps; (i) NH2NH2, EtOH, 50 °C; (j) 4,5-dibromo-2-trichloroacetylpyrrole, Na2CO3, DMF, 76% for 2 steps; (k) AcCl, MeOH/EtOAc, 99%; (l) H2/Pd-Lindlar, MeOH/THF, 84%.

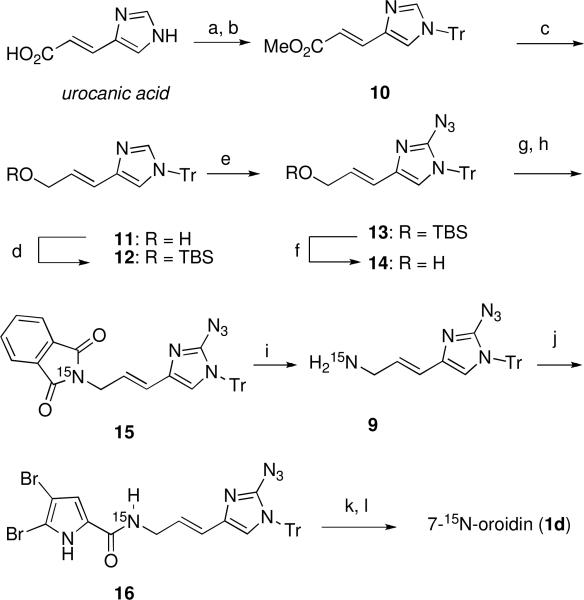

The 1H, 13C and 15N NMR spectra and mass spectra were fully consistent with the structure and location of the 15N label as depicted. The FTMS of natural oroidin (1a, Figure 2) shows the expected 1:2:1 pattern for the pseudomolecular ion [M+H]+ associated with the 79Br and 81Br isotopomers (m/z 387.93990, Δmmu = –0.41 mmu). The FTMS spectrum of 7-15N-oroidin (1d) (Figure 2b) shows the same ion pattern, only the distribution is increased by 1 amu (m/z 388.93719, Δmmu = –0.16). Less than 2% of the 14N isotopomer was detected which is consistent with the reported purity of the 15N-pthalimide (>98% atom 15N) employed in the synthesis.

Figure 2.

MALDI FTMS (7T) expansions of the pseudomolecular ion [M+H]+ of oroidin for (a) natural 1a (C11H12Br214N5NO) and (b) 7-15N-oroidin (1d), C11H12Br2Br214N415NO, >98% atom 15N. Mass accuracy = 1ppm.

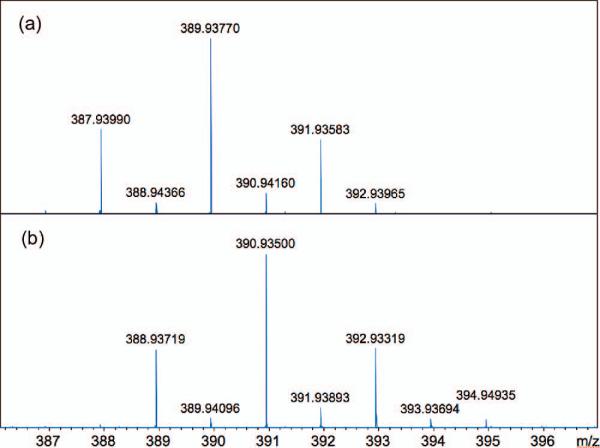

Two general methods are available for measuring incorporation of the stable isotope 15N into natural products by pulse labeling – mass spectrometry and NMR. In both techniques, the level of isotopic enrichment from de novo biosynthesis of derived PIAs must exceed the background 15N present of extant PIAs within the sponge and, for MS in particular, 15N background contributions from other nitrogen atoms in the molecule. As a stable isotope label, 15N is preferable to 13C because the natural abundance of the heavier to lighter isotope for N (~0.3%) is only about 1/4 of C (~1.1%). 15N incorporation will, therefore, be easier to detect. Ideally for 15N incorporation experiments, mass spectrometry should differentiate the contributions to the M+1 peak from 15N and 13C,xxiv a task best-suited to Fourier transform MS (FTMS) with exceptionally high resolution (7T field, R = 240,000) that should be capable of resolving the nominal M+1 peak of the pseudomolecular ion into individual isotopomer contributions from species containing one 13C or one 15N. Baseline separation of the isotopomers was readily achieved by MALDI FTMS (Figure 3), allowing quantitation of the 15N isotopomer peak. For oroidin (1a), the critical difference in the mass of 12C-15N containing ions versus the heavier 13C-14N isotopomer amounts to only 0.00632 amu, a baseline separation not readily achievable by high-resolution mass spectrometers with conventional analyzers (e.g. double sector, TOF).

Figure 3.

MALDI FTMS (7T) expansions of m/z and peak height, h, for the ‘M+1’ peak of the pseudomolecular ions of oroidin (C11H11Br2N5O). Mass accuracy = 1 ppm (R = 240,000). (a) natural 1a. (b) 1a + 1d (0.04 mol equiv). (c) 1a + 1d (0.10 mol equiv). Peak assignments of [M+H]+ in (c): m/z 388.94372, 12C1013CH12Br2N5O+; m/z 388.93739; 12C11H12Br2N415NO+. The unrelated peak at m/z 388.9305 (indicated with an ‘*’) is tentatively assigned to some loss of H from the dominant 79Br/81Br isotopomer, C11H1079Br81BrN5O+ ([M]+, Δmmu = –0.5).

Quantitation of the 15N isotopomer can be made from integration of ion current intensities of the [M+1] components, 15N-12C and 14N-13C (Figure 3). Assuming the 13C abundance in natural and synthetic 15N-labeled oroidin are identical, the 13C peak intensity may be used as the denominator in the ratio h (Equation 1), where hN and hC are the respective measured peak heights of the 15N-12C and 14N-13C component ions.

| (Eqn 1) |

Consequently, h can be used to reflect small changes in the 15N content.xxv From the ion current peak heights measured in the FTMS spectrum of natural oroidin (1a), h was found to be 0.1487±0.0175. A prepared ‘mock’ labeled sample (‘Mix1’), consisting of a 1:0.005 mixture of oroidin (1a): 7-15N-oroidin (1d), showed an enhanced h of 0.1881±0.0135 corresponding to a ~4% 15N enrichment. A second sample (‘Mix2’, 1:0.100, 1a:1d) gave h = 1.024±0.0369, corresponding to ~88% 15N enrichment. We estimate that the limit of detection (LOD, ±3 σ) for 15N incorporation corresponds to an increase in intensity, Δh ~5.2%. Given that natural abundance of 15N is approximately 0.3% atom, this would amount to observation of as little as 10.4 parts per thousand of 15N incorporation per N atom of oroidin (1a) by de novo synthesis. Detection of this small amount will, of course, be made more difficult by the presence of unlabeled oroidin (1a) within the sponge.

The disadvantage of analysis of 15N-content in oroidin and other PIAs by MS is the presence of at least five N atoms, each contributing to the intensity of 15N-12C component of the M+1 peak. Consequently, it may be expected the actual LOD by FTMS will be higher.

Direct detection of 15N incorporation by 15N NMR spectroscopy is impractical due to low natural abundance and severely compromised sensitivity of this I= ½ nucleus which possesses a low-magnitude, negative magnetogyric ratio (γ = – 4.31726570 MHz T–1).xxvi Conveniently, 1H-15N HSQC circumvents most of these problems by indirect detection of bonded 1H-15N couplets through magnetization transfer from 15N and observation of the more sensitive 1H nucleus. Because four of the five N atoms in oroidin (1a) are bonded to H, 2D 1H-15N HSQC can provide bond-specific information about fractional enrichment at an individual N atom in oroidin and, by extension, more complex PIAs by measurement of the 1H-15N couplet intensity. The intensity of cross peaks in the 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of oroidin will vary for each N-H couplet depending on efficiency of magnetization transfer that largely depends upon the magnitude of the 1JNH scalar coupling constant. Nevertheless, the intensity of each crosspeak will scale linearly as a function of 15N abundance.

When put to practice, it is easier and more meaningful to measure 15N enrichment from the volume integration of cross peaks of 2D HSQC spectra or – best of all – from the 1D version of the HSQC experiment where evolution of the F1 dimension (15N chemical shift) is eliminated and acquisition time is devoted to improving S/N in the detected dimension F2 (1H chemical shift). We define here ΔI as the difference of cross peak intensity, I, of the 15N-labeled N-H couplet of interest (in this case, the NH(C=O) signal of 1d) in a sample of oroidin (1a), spiked with a known amount of 7-15N-oroidin (1d), compared to the intensity, I0, of oroidin recorded under the same conditions (Equation 2). The values of I are normalized to the intensity of the pyrrole N-H couplet of oroidin, Ipy, in each experiment.

| (Eqn. 2) |

We elected to use the pyrrole N-H couplet of oroidin (1a) (δH = 13.14, s; δN169.1) as the control because of its ready assignment from 1H-15N HMBC, lack of tautomerism, and likely origination in a different biosynthetic pathway unaffected by biosynthetic incorporation of 15N into the amino-imidazole fragment (see Discussion).

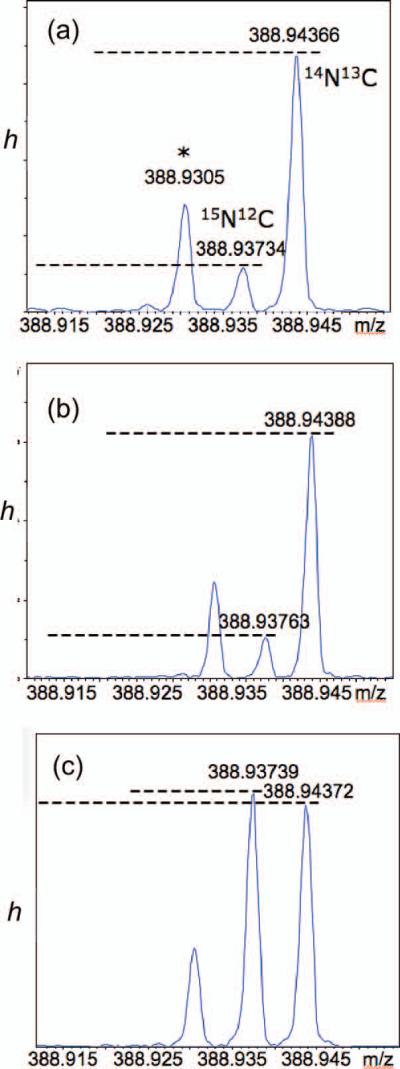

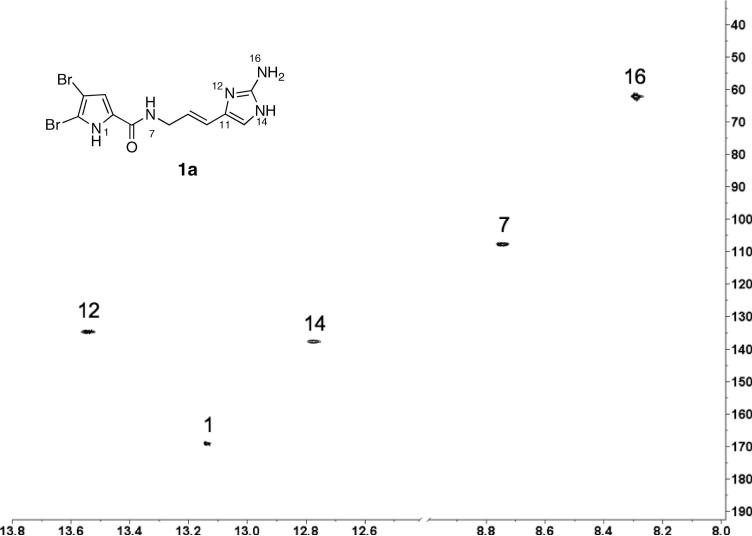

The exquisite mass-sensitivity of the triple-tuned {13C,15N}1H 1.7 mm 600 MHz microcryoprobe was used to full advantage in this work for characterization of the 15N content of oroidin samples. This low-volume, high-mass sensitivity cryoprobe allowed measurements of samples of only ~1.5 mg in 30 μL (acquisition times, ~4 h). Figure 4 shows the 2D 1H-15N HSQC experiment for oroidin (1a) with respective N assignments (also, see the Experimental for accurate δ's). A single dominant cross peak was observed in the 2D 1H-15N HSQC of 7-15N-oroidin (1d) (not shown), confirming the location of the 15N label at the amide group N-H (δH = 8.75, t, 3JHH = 6.0 Hz, H7; δN = 107.8, Ν7), as expected.

Figure 4.

2D 1H-15N HSQC (600 MHz, 1:1 DMSO-d6/benzene-d6) of natural oroidin (1a, depicted tautomer is arbitrary). N locants are labeled following the numbering scheme of Assman and Köck (Ref.xxxii). ns = 16, T2, T1 = 2K × 256; F2, F1 = 2K × 1K; d1 =1.5s

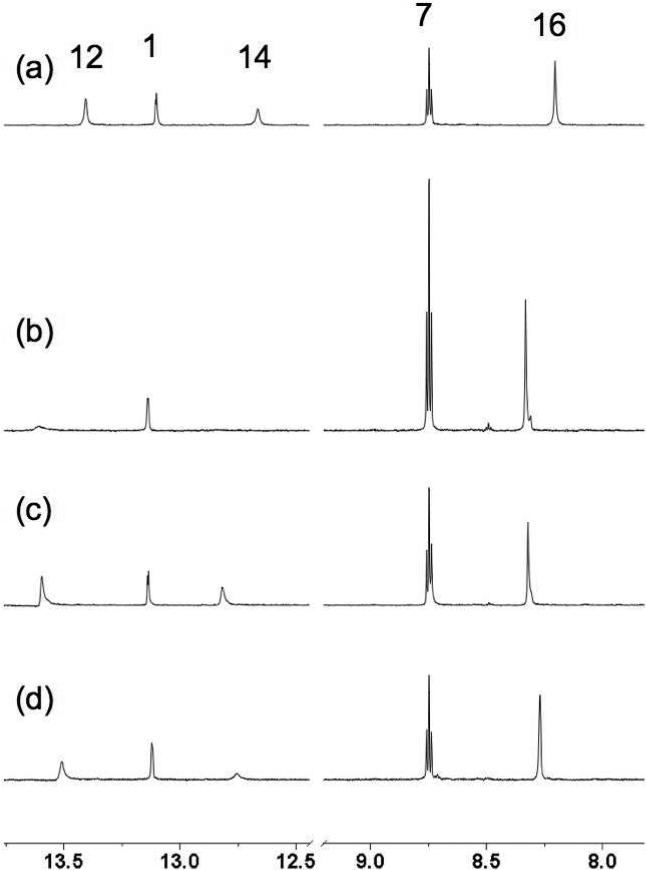

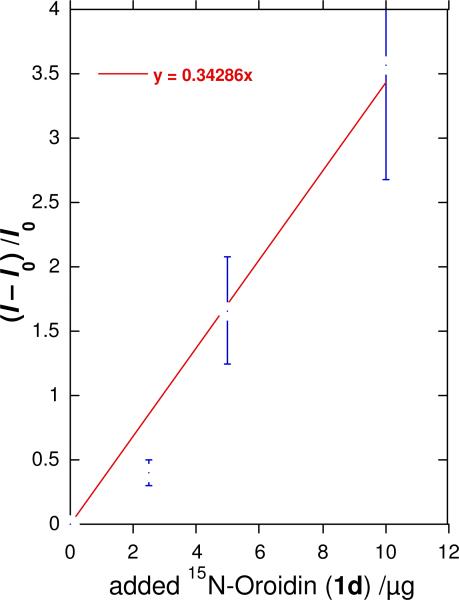

Figure 5a-c shows 1D 1H-15N HSQC experiments of oroidin (1a) spiked with different amounts of 7-15N-oroidin (1d) and the integrals of each N-H couplet, normalized to the N1-pyrrole couplet are reported in Table 1 (note that the integrals are not exactly proportional to the stoichiometric ratios of attached H's). As predicted, the value of ΔI increases linearly with the amount of added 7-15N-oroidin (1d) and the slope of this ‘standards addition’ linear regression (Figure 6) gives the proportionality constant c = 0.34 for ΔI per μg of added 1d. It should be noted that this value will be highly dependent upon the pulse sequence parameters and conditions used for NMR acquisition.

Figure 5.

1D 1H-15N HSQC experiments (1H δ, 1.7 mm microcryoprobe, 600 MHz) of 1a with N-H assignments. Labels indicate N atom assignments made from a separate 1H-15N HMBC experiment (not shown). (a) 1500 μg of 1a, no added [15N]-1d. (b) 1500 μg 1a + 10 μg 1d. (c) 1500 μg 1a + 5.0 μg 1d. (d) 1500 μg 1a + 2.5 μg. Relaxation delay, d1 = 1.50 s, optimized for 1JN-H = 90 Hz; 1H π/2 pulse = 12 μS, 15N π/2 pulse = 34 μS; NA = 6K; dummy scans = 16; NI = 1; T2 = F2= 8K points (no zero fill). See Supporting Information for calculations of limit of detection (LOD), mean and SD.

Table 1.

Integrals from 1H-15N 1D HSQC of natural oroidin (1a, 1.5 mg/ 30 μL) and 1a 'spiked ' with 1d. Integrals of H-N couplets corresponding to N-12, N-14 and N-16 vary due to tautomerism.

| Aliquot μg 1d | N-12 | N-1 | N-14 | N-7 | N-16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 1.26 | 1.00 | 1.05 | 2.17 | 2.14 |

| 2.5 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.48 | 2.57 | 2.23 |

| 5.0 | 1.65 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 3.83 | 2.55 |

| 10.0 | 0.63 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 5.74 | 3.02 |

Figure 6.

Linear regression of 1H-15N HSQC cross-peak integral ratio, (I–I0)/I0 for the NH(C=O) signal in ‘mock’ pulse labeling experiments with natural abundance 1a (1500 μg, I0) spiked with measured aliquots of 1d (μg, ‘x-scale'). Observed values, I, for the NH-C=O 1H-15N couplet are normalized to the intensity of Ipy the pyrrole N-H cross peak. For the NH(C=O) peak in the natural abundance sample (no added 1d), I = I0 and I0/Ipy = 1.00. Error bars are ± SD.

Constant c will be useful for estimation of absolute %N incorporations in PIAs labeled during in-field incorporation experiments of secondary metabolism within living sponges. Although it is advisable to measure the relative HSQC intensities of pyrrole N-H couplet and NH(C=O) couplets of the specific PIA in question, it may be reasonably expected that the magnetic properties of these couplets in more complex PIAs are comparable to those of oroidin (1a). We estimate the limit of detection (LOD) for 15N enrichment by HSQC in 1a to be approximately 1.5 parts per thousand (based on ±3 SD). This is more sensitive than the LOD of 15N-enrichment by FTMS, the reason being HSQC detection of couplet 15N-1H at each N atom and eliminates background ‘dilution’ by other 15N's, however the precision is inferior to FTMS replicate measurements.

Biosynthetic Considerations

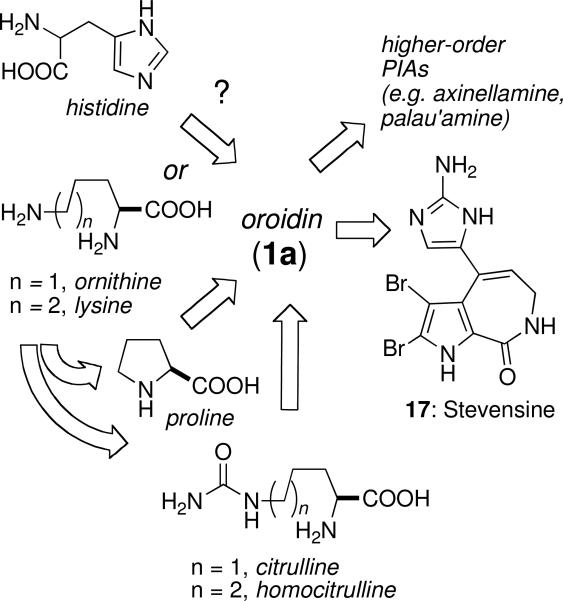

Two phases of PIA biosynthesis can be considered: the assembly of oroidin (1a), and downstream conversion of the latter to more complex PIAs. Despite much speculation, on the biosynthesis of PIAs, only one experimental study in living marine sponges has appeared to date. The precursor for the imidazole side chain is probably an amino acid and both histidine and ornithine have been proposed.xxvii Kerr and co-workers found that cultured cells of Teichaxinella morchella (Styllisa caribicaxxviii) produced 14C-labeled stevensine (17),xxix the simplest monomeric PIA related to oroidin (1a), upon exposure to U-14C-labeled histidine or C5-14C-ornithine, but not U-14C-arginine (Figure 7).xxvii Paradoxically, U-14C-histidine was incorporated into 17, but this would require an additional C1 unit from an unidentified source to complete the imidazole ring and a non-intuitive substitution of NH2 at C-2 of the imidazole ring. No simple mechanism for this scenario presents itself. Alternatively, citrulline from the N-carbamoylation of ornithine, may be the precursor to the side chain of oroidin; however ornithine is also a precursor for the biosynthesis of the pyrrole group; this hypothesis would not be resolved by labeled ornithine incorporation experiments. Ornithine, if it is the precursor to oroidin (1a), must undergo decarboxylation, amide coupling with a suitable pyrrole carboxylate group, N-carbamoylation to citrulline, oxidative N-insertion into the side chain and aromatization of the heterocyclic product to give the nascent 2-aminoimidazole ring (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Possible biosynthesis of oroidin (1a) and conversion to stevensine (17)

These uncertainties in the origin of oroidin (1a) are, in theory, addressable by suitable 15Nlabeled amino acid incorporation experiments. Unfortunately, low levels of radioactivity and specific incorporation levels were observed with amino acids in the Kerr experiment ([U-14C]-His, 1460 dpm (0.026%) and [U-14C]-ornithine, 1300 dpm (0.024 %), respectivelyxxvii), presumably, a consequence of the low numbers of cultured cells used (5 x 107) and higher metabolic mobilization and dilution of 14C-labeled amino acids into other committed pathways of primary metabolism. Consequently, detection of 15N incorporation into PIAs using 15N-labeled amino acids may be precluded by the limits of detection. For the above reasons, late-stage precursors (e.g. 7-15N-oroidin (1d), sceptrin (2) and ageliferin (3) are attractive for mapping the origin of downstream polycyclic PIAs since these molecules should be committed intermediates. Measurement of their rates of incorporation into PIAs in living sponges of the genera Agelas, Stylissa and Ptilocaulis may also provide critical data on the rates of marine alkaloid secondary metabolism for which there is no current information.

The use of precursors labeled with the spin I=1/2 stable isotope 15N is particularly attractive as it provides bond-specific information regarding the flow of intermediates in biosynthesis of complex PIAs. Judicious design and placement of the label in 15N-labeled oroidin is important. Because the primary NH2 group of the aminoimidazole group is potentially metabolically labile through deamination reactions, we chose to label the amide bond in 15N-oroidin. Quantitation of 15N incorporation into proteins has been made from integration of cross peak volumes of 2D HSQC experiments;xxx however, in the present work with natural products we show that it is far simpler to integrate the corresponding 1D HSQC spectra.

Finally, although the ratio of sceptrin to ageliferin found in one sample of Agelas conifera is ~10:1,xxxi the ratios of mono-brominated and dibrominated analogs of sceptrin and ageliferin vary slightly from approximately 1:1 ~ 3:4; however, these data do not clearly indicate an ordering for a bromination-dimerization sequence in the biosynthesis of dimeric PIAs. Propagation of 7-15N-oroidin (1d) along the biosynthetic pathway to complex PIAs will carry the 15N label through symmetrical and non-symmetrical intermediates and detection of residual 15N in strategically chosen N-H bonds in the molecule should reveal timing, ordering and molecularity of the C-C bond-forming events and the extent of coupling of de novo enzymatic reactions. HPLC analysis of PIA-containing extracts from A. conifera (Agelasidae), collected in the Florida Keys by Köck and coworkers,xxxi show the presence of sceptrin (2) and ageliferin (3), however, some specimens of Agelas sceptrum collected by us contained sceptrin (2) but were devoid of the expected precursors 1a-c. If 1a-c are precursors to other PIAs, as is highly probable, this implies that the rates of conversion of 1a-c to higher-order PIAs are highly dependent upon the sponge species, their biosynthetic capacities, and possibly the habitats they occupy. 7-15N- Oroidin (1d) should find great value in systematic studies of the time-dependent biosynthesis of PIA natural products by pulse labeling in live sponges to answer some of these questions.

Conclusion

A concise, gram-scale synthesis of 15N-labeled oroidin from commercially available and inexpensive urocanic acid has been achieved. 15N-Oroidin, or its debromoanalogs, may be utilized in biosynthetic feeding experiments to elucidate likely intermediates in the biosynthesis of complex members of the pyrrole-imidazole marine alkaloid family, including palau'amine and axinellamine. FTMS detection of 15N offers unparalleled sensitivity (picomole) and 1H-15N HSQC provides bond-specific information. The utility of 1H-15N HSQC experiments for detection of site-specific 15N incorporation in a mock pulse-labeling experiment has been demonstrated. Several advantages of 15N pulse labeling of biosynthetic pathways are apparent, especially for in-field experiments carried out with living marine invertebrates. The 15N NMR chemical shift was exploited through indirect 1H-15N HSQC to afford enhancement of otherwise weak 15N signals by polarization transfer through N-H couplets. 15N incorporation was further amplified by the enhanced mass-sensitivity of the triple-tuned 1H{13C,15N}-600 MHz 1.7 mm microcryoprobe. Biosynthetic studies with alkaloids bearing N-H groups that are not complicated by exchange or tautomerism afford the best cases for application of the technique. In principle, even alkaloids lacking N-H couplets (tertiary N compounds) are amenable to study by detection of long-range 1H-15N couplets from HMBC experiments. The use of 15N stable isotope avoids more complex logistics associated with radioactive tracers (e.g. 14C, 3H) that often preclude laboratory operations aboard seagoing research vessels. The results of field incorporation experiments with 7-15N-oroidin (1d) will be reported in due course.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

IR spectra were recorded on thin films using a Jasco 4100 FTIR by attenuated total reflectance (ATR) on samples mounted on a 3 mm ZnSe plate. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker DRX 600 MHz equipped with 1.7-mm {13C,15N}1H 600 MHz CPTCI microcryoprobe, JEOL 500 MHz spectrometer equipped a 5 mm {13C }1H probe or Varian 400 and 500 MHz spectrometers equipped with 5 mm {13C}1H room temperature probe and 5 mm {1H}13C cryoprobe, respectively. NMR spectra are referenced to residual solvent signals (CHCl3, 1H, δ 7.26 ppm; CDCl3, 13C, δ 77.16 ppm) or the internal offset for 15N assigned by the instrument manufacturer (Bruker). HRMS measurements of synthetic compounds were made at the Laboratory for Biological Mass Spectrometry (Texas A&M University), Scripps Research Institute (TOF-MS) or University of California, San Diego (EI-MS) mass spectrometry facilities. MALDI FTMS were recorded on a 7T Bruker Apex QFTMS. LCMS was carried out on a ThermoFisher Accela UHPLC coupled to an MSQ single quadrupole mass spectrometer operating in positive ion mode, unless otherwise stated. Semi-preparative HPLC was carried out on a Varian SD200 system equipped with a dual-pump and UV-1 UV detector under specified conditions. All solvents for purification were of HPLC grade. See Supporting Information for other procedures.

Synthesis of 7-15N-Oroidin (1d)

To a solution of amide 16 (380 mg, 0.58 mmol) in 20 mL of EtOAc was added MeOH (1.17 mL, 28.9 mmol) followed by dropwise addition of AcCl (2.06 mL, 28.9 mmol) (to generate HCl) at 0 °C. The solution was stirred for 1.5 h at 25 °C and during that time a precipitate formed. The reaction mixture was filtered to separate the solid product of azidoimidazole hydrochloride salt (240 mg, 99%), which was of sufficient purity for the next reaction: IR (thin film) 3115, 233, 2150, 1611, 1555, 1439 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ4.11 (d, J = 5 Hz, 2H), 6.35 (dt, J = 16, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 6.43 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1H), 6.89 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 7.31 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) δ42.3 (d, JC-N = 114 Hz), 100.8, 107.3, 115.2, 116.3, 117.5 (d, JC-N = 22.5 Hz), 129.4 (d, JC-N = 106 Hz), 131.8, 132.3, 142.6, 162.4 (d, JC-N = 174 Hz); HRESIMS m/z 416.9171 [M+H]+ (calcd for C11H12Br2N 156NO, 416.9163).

To a solution of the azidoimidazole hydrochloride salt (210 mg, 0.50 mmol) in 30 mL of MeOH/EtOAc (1 : 1) was added Lindlar's catalyst (100 mg, 5% Pd on CaCO3, poisoned with Pb). The resulting mixture was stirred under atmospheric hydrogen at 25 °C for 6 h then filtered with MeOH through a pad of Celite. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to leave a residue, which was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel (gradient elution: 10:1:0 → 1:1:0.01 CH2Cl2/MeOH/NH4OH) to furnish 7-15N-oroidin (1d) (165 mg, 84%): IR (thin film): 3304, 2363, 2339, 1620, 1507, 1415 cm−1; 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3OD) δ 4.00 (d, J = 6 Hz, 2H), 5.87 (dt, 3JNH = 16 Hz, 3JHH= 6 Hz, 1H), 6.30 (d, J = 16 Hz, 1 H), 6.47 (s, 1H), 6.83 (d, J = 1 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CD3OD) δ 43.1 (d, 1JC-N = 106 Hz), 100.7, 107.0, 115.1, 118.5, 122.2, 123.6 (d, 2JC-N = 15 Hz), 129.7 (d, 1JC-N = 99 Hz), 132.2, 152.8, 162.4 (d, 1JC-N = 175 Hz); HRESIMS m/z 390.9289 [M+H]+ (calcd for C11H12Br2N415NO, 390.9258).

See Supporting Information for additional procedures.

Isolation of Natural Oroidin (1a) from Stylissa caribica

A sample of Stylissa caribica (wet wt. 24.5 g) was collected in the Bahamas (June 2008) and extracted with 1:1 CH2Cl2/MeOH (rt, overnight, 2 × 500 mL). The solvent was removed under reduced pressure and the residue partitioned between hexanes (3 × 250 mL) and 9:1 MeOH/H2O (250 mL). The aqueous MeOH layer was concentrated and further partitioned between n-BuOH (3 × 250 mL) and H2O (250 mL). Removal of the solvent from the upper layer gave an n-BuOH extract (787 mg), a portion of which (191 mg) was adsorbed onto a solid phase extraction cartridge (C18) and eluted with 4:1 CH3CN/H2O, followed by THF. The first-eluting fraction (116 mg) was separated by gradient HPLC (C18, 10:90 to 60:40 CH3CN/H2O + 0.1% TFA) to give oroidin 1a (8.8 mg, 1.0% wt weight).

MALDI FTMS of Oroidin (1a) and 7-15N-Oroidin (1d)

Matrix solution (1 μL of saturated α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (CHCA) solution in 50:50:0.2 MeOH:H2O:TFA) was added to 1 μL of the sample solution (1 pmol/μL) and the sample (approximately 1 pmol) deposited onto a stainless steel target. For each sample, 200 shots were acquired for each mass spectrum (acquisition time, ~1 minute each), and 24 spectra were co-added. Data were processed using Bruker software and error analysis was carried out using standard deviation of replicate MS measurements (N≥5).

1D 1H-15N HSQC Experiments

Samples for mixing experiments were prepared by addition of measured aliquots of a standard solution of 1d (1.25 mg/10 mL MeOH) to a sample of 1a (1500 μg). The samples were concentrated by removal of solvent (MeOH + 0.05% TFA), and redissolved in 1:1 DMSO-d6/benzene-d6 (35 μL) before transferring ~30 μL to a NMR tube (ϕ = 1.7 mm) using a gas-tight syringe. 1D 1H-15N HSQC NMR spectra were acquired with 8K data points in T2 (no zero-fill) and optimized for 1JN-H = 90 Hz. Each experiment was preceded by 16 dummy scans and ~6K scans were collected. The corresponding 1H-15N integrals were averaged and normalized against the N1 pyrrole couplet of 1 (IP = 1.000). See Table 1 (numbering system follows that of Assman and Köckxxxii). 1H-15N assignments: δH, δN (1:1 DMSO-d6/C6D6): 13.14, 169.1 (N1); 8.75, 107.8 (N7); 13.54, 134.7 (N12); 12.78, 137.7 (N14); 8.21, 62.2 (N16).

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Oroidin (1a) and other representatives of the pyrrole-imidazole alkaloid (PIA) family from marine sponges.

Acknowledgment

We thank A. Jansma (UCSD) for assistance with NMR, J. Pawlik (UNC Wilmington), and the captain and crew of the RV Seward Johnson for logistical support during collecting expeditions and in-field assays. We are grateful to the NIH (GM052964 DR & TFM) and the Welch Foundation (A-1280) for generous support.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the late Dr. John W. Daly of NIDDK, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland and to the late Dr. Richard E. Moore of the University of Hawaii at Manoa for their pioneering work on bioactive natural products

Supporting Information Available.

Synthetic procedures and 1H and 13C NMR spectra for 1d, 9-16, other intermediates and calculation of LOD for 1H-15N HSQC experiments. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- i.Recent examples of syntheses of pyrrole-imidazole alkaloids: Arndt H-D, Koert U. In: Organic Synthesis Highlights 4. Schmalz H-G, editor. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2000. p. 241.; Hoffmann H, Lindel T. Synthesis. 2003:1753–1783.; Jacquot DEN, Lindel T. Curr. Org. Chem. 2005;9:1551–1565.; Du H, He Y, Sivappa R, Lovely C. J. Synlett. 2006:965–992.; Kock M, Grube A, Seiple IB, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. 2007;119:6706–6714. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701798.; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:6586–6594. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701798.; Weinreb SM. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007;24:931–948. doi: 10.1039/b700206h.; For some publications not covered in the these reviews, see: Dransfield PJ, Dilley AS, Wang S, Romo D. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:5223–5247.; Wang S, Dilley AS, Poullennec KG, Romo D. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:7155–7161.; Nakadai M, Harran PG. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:3933–3935.; Tan X, Chen C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:4345–4348. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601208.; Overman LE, Paulini R, White NS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12896–2900. doi: 10.1021/ja074939x.; O'Malley D, Yamaguchi J, Young IS, Seiple IB, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3581–3583. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801138. ; Yamaguchi J, Seiple IB, Young IS, O'Malley DP, Maue M, Baran PS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3578–3580. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705913.; Bhandari MR, Sivappa R, Lovely CJ. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1535–1538. doi: 10.1021/ol9001762.

- ii.Al Mourabit A, Potier P. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- iii.Walker RP, Faulkner DJ, VanEngen D, Clardy J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:6772–6773. An variation on the sceptrin skeleton, embodying an unusual benzocyclobutane (benzosceptrins A and B), has just been reported. Appenzeller J, Tilvi S, Martin M-T, Gallard J-F, El-bitar H, Dau ETH, Debitus C, Laurent D, Moriou C, Al-Mourabit A. Org. Lett. 2009;11:4874–4877. doi: 10.1021/ol901946h.

- iv.a Keifer PA, Koker MES, Schwartz RE, Hughes RG, Jr., Rittschof D, Rinehart KL. 26th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy; New Orleans. Sep. 28–Oct. 1, 1986; No. 1281. [Google Scholar]; b Rinehart KL. Pure Appl. Chem. 1989;6:525–528. [Google Scholar]; c Kobayashi J, Tsuda M, Murayama T, Nakamura H, Ohizumi Y, Ishibashi M, Iwamura M, Ohta T, Nozoe S. Tetrahedron. 1990;46:5579–5586. [Google Scholar]; d Keifer PA, Schwartz RE, Koker MES, Hughes RG, Rittschof D, Rinehart KL. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:2965–2975. [Google Scholar]; e Williams DH, Faulkner DJ. Tetrahedron. 1996;52:5381–5390. [Google Scholar]

- v.Nishimura S, Matsunaga S, Shibazaki M, Suzuki K, Furihata K, van Soest RWM, Fusetani N. Org. Lett. 2003;5:2255–2257. doi: 10.1021/ol034564u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vi.a Kinnel RB, Gehrken H-P, Scheuer PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3376–3377. [Google Scholar]; b Kinnel RB, Gehrken H-P, Swali R, Skoropowski G, Scheuer PJ. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:3281–3286. [Google Scholar]

- vii.a Bascombe KC, Peter SR, Tinto WF, Bissada SM, McLean S, Reynolds WF. Heterocycles. 1998;48:1461–1464. [Google Scholar]; b Urban S, de A. Leone P, Carroll AR, Fechner GA, Smith J, Hooper JNA, Quinn RJ. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:731–735. doi: 10.1021/jo981034g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- viii.Grube A, Kock M. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4675–4678. doi: 10.1021/ol061317s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ix.D'Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Debitus C, Ribes O, Pusset J, Leroy S, Pietra F. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1993:1305–1306. [Google Scholar]

- x.D'Ambrosio M, Guerriero A, Chiasera G, Pietra F. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1994;77:1895–1902. [Google Scholar]

- xi.Hong TW, Jímenez DR, Molinski TF. J. Nat. Prod. 1998;61:158–161. doi: 10.1021/np9703813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xii.a De Nanteuil G, Ahond A, Guilhem J, Poupat C, Tran Huu Dau E, Potier P, Pusset M, Pusset J, Laboute P. Tetrahedron. 1985;41:6019–6033. [Google Scholar]; b Poullennec KG, Romo D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6344–6345. doi: 10.1021/ja034575i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Imaoka T, Iwammoto O, Noguchi K, Nagasawa K. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:3799–3801. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiii.Mason CK, McFarlane S, Johnston PG, Crowe P, Erwin PJ, Domostoj MM, Campbell FC, Manaviazar S, Hale KJ, El-Tanani M. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2008;7:548–558. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xiv.Foley LH, Büchi G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:1776–1777. [Google Scholar]

- xv.Baran PS, O'Malley D, Zografos A. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:2674–2677. doi: 10.1002/anie.200453937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xvi.Baran was unable to convert 2 to 3 under photochemical conditions, however, thermal isomerization of 2 to 3 was achieved under microwave irradiation (195 °C, 1 min, 40% yield and 52% recovered starting material). See Reference xva.

- xvii.Hoffmann H, Lindel T. Synthesis. 2003:1753–1783. and references cited. [Google Scholar]

- xviii.a Birman VB, Jiang X-T. Org. Lett. 2004;6:2369–2371. doi: 10.1021/ol049283g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Papeo G, Frau MAG-Z, Borghi D, Varasi M. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:8635–8638. [Google Scholar]; c Yang C-G, Wang J, Jiang B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:1063–1066. [Google Scholar]

- xix.a Baran PS, Zografos AL, O'Malley DP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:3726–3727. doi: 10.1021/ja049648s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Huigens RW, Richards JJ, Parise G, Ballard TE, Zeng W, Deora R, Melander C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6966–6967. doi: 10.1021/ja069017t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xx.a Nanteuil GD, Ahond A, Poupat C, Thoison O, Potier P. Bull. Soc. Chim. Fr. 1986:813–816. [Google Scholar]; b Commerçon A, Paris JM. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:4905–4906. [Google Scholar]; c Danios-Zeghal S, Mourabit AA, Ahond A, Poupat C, Potier P. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:7605–7614. [Google Scholar]; d Lindel T, Hochgürter M. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:2806–2809. doi: 10.1021/jo991395b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Berree F, Bleis PG, Carboni B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:4935–4938. [Google Scholar]

- xxi.Lovely CJ, Du H, Sivappa R, Bhandari MR, He Y, Dias HVR. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:3741–3749. doi: 10.1021/jo0626008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxii.a Pirrung MC, Pei T. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:2229–2230. doi: 10.1021/jo991630q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Dolensky B, Kirk K. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3468–3473. doi: 10.1021/jo0200419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxiii.See Supporting Information for details.

- xxiv.Deuterium 2H (~0.02%) and 17O (~0.04%) also contribute to M+1, but are much lower in natural abundance (~0.02% and 0.04%, respectively) and may be ignored in the first approximation.

- xxv.The 13C/15Nisotope ratio of synthetic and natural oroidin samples may differ slightly due to differences in fractionation of 13C (or 15N) in compounds derived by ‘modern’ biosynthesis compared to chemical precursors derived from petrochemical based feedstock. In practice, this will be inconsequential, since corrections can be made with the appropriate normalization.

- xxvi.The value here, given in commonly used units of γ/2π, was converted from the value cited in the IUPAC 2001 recommendations [–2.71261804 = γ/107 (rads–1T–1)]. Harris RK, Becker ED, Cabral de Menezes SM, Goodfellow R, Granger P. Pure Appl. Chem. 2001;73:1795–1818.

- xxvii.Andrade P, Willoughby R, Pomponi S, Kerr R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:4775–4778. [Google Scholar]

- xxviii.Teichaxinella morchella has synonymity with Axinella corrugata and is probably the same as Stylissa caribica. http://www.spongeguide.org/speciesinfo.php?species=110

- xxix.Stevensine was named in honor of the late Professor Robert V. Stevens (Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, University of California, Los Angeles). Albizati K, Faulkner DJ. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:4163–4164.

- xxx.Englander J, Cohen L, Arshava B, Estephan R, Beckers JM, Naider F. Biopolymers. 2006;84:508–518. doi: 10.1002/bip.20546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxi.Assman M, Köck MZ. Naturforsch. 2002;57c:157–160. doi: 10.1515/znc-2002-1-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- xxxii.Assman M, Zea S, Köck M. J. Nat. Prod. 2001;64:1593–1595. doi: 10.1021/np010350e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.