Abstract

This community-based participatory research (CBPR) study was based on patient navigation (Navigator) among three original sites: Colorado, Michigan, and South Dakota. During 2010, the study added two sites: the Comanche Nation and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation (Oklahoma). The intervention includes 24-h of a Navigator-implemented cancer education program that addresses the full continuum of cancer care. The partners include agreements with up to two local Native American organizations each year, called Memorandum Native Organizations, who have strong relationships with local American Indians. Family fun events are used to initiate the series of workshops and to collect baseline data and also to wrap up and evaluate the series 3 months following the completion of the workshop series. Evaluation data are collected using an audience response system (ARS) and stored using an online evaluation program. Among the lessons learned to date are: the Institutional Review Board processes required both regional and national approvals and took more than 9 months. All of the workshop slides were missing some components and needed refinements. The specifics for the Memorandum Native Organization deliverables needed more details. The ARS required additional training sessions, but once learned the Navigator use the ARS well. Use of the NACR website for a password-protected page to store all NNACC workshop and training materials was easier to manage than use of other online storage programs. The community interest in taking part in the workshops was greater than what was anticipated. All of the Navigators’ skills are improving and all are enjoying working with the community.

Keywords: American Indian, Native American, Cancer, Navigator, Patient navigation

Introduction

Native American Cancer Research Corporation (NACR) staff has implemented community-based participatory research (CBPR) since 1988 and began patient navigation (also called, Native Sisters) programs in 1994 [1–6]. The initial programs focused on early detection and screening; then evolved into programs addressing patient support after diagnosis with cancer. The Native communities are very mobile (going back and forth between the city and reservation for several months to several years at a time) and community members frequently were receiving cancer treatment before connecting or re-connecting with the NACR Navigators. Because our patient navigation system is community-based, new strategies were needed to elevate the awareness and availability of the Navigators. NACR collaborated with the Intertribal Council of Michigan, Incorporated (ITCMI), and Rapid City Regional Hospital’s “Walking Forward” Program in partnership with the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Health Board (GPTCHB, formerly known as the Aberdeen Area Tribal Chairmen’s Health Board) to design an education intervention to increase local Navigators’ visibility as well as to improve Native community members’ cancer knowledge and participation in prevention and early detection services. The subsequent 5-year intervention is called “Native Navigators and the Cancer Continuum” (NNACC; National Institutes of Health, National [PI: Burhansstipanov, NIH, NCMHD R24MD002811]).

Description of NNACC

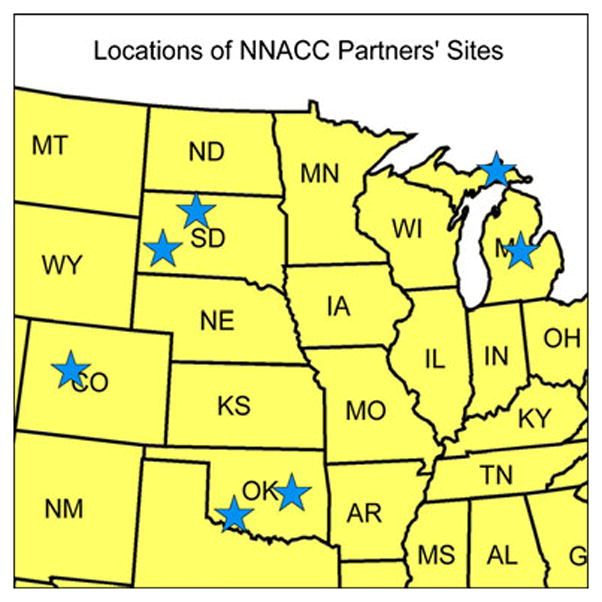

Initially, this CBPR study was based on patient navigation among three sites: NACR, Colorado; ITCMI, Michigan, and RCRH “Walking Forward” program in partnership with the GPTCHB, South Dakota (see Fig. 1). During 2010, the study added two sites and partners: the Comanche Nation (PI: Eschiti, R15 NR 012195) and the Muscogee (Creek) Nation of Oklahoma (PI: Burhansstipanov, R24MD002811-S2; see Fig. 1). The partners have equal decision-making roles through all aspects of the project as well as an equal budget to conduct the intervention. Each site has two Native patient navigators and also collaborates with at least two local Native American organizations that have a strong presence and credibility within their respective Native American communities (called Memorandum Native Organizations).

Fig. 1.

Locations of NNACC partners’ sites

The NNACC goal is for partners to collaborate, refine, expand, and adapt various navigator/community education programs to address the Native American communities’ and their members’ needs throughout the continuum of cancer care (prevention, early detection, diagnosis, treatment, survivorship, palliation, and end-of-life). The research question is, “Can a Native specific comprehensive Navigator-initiated community cancer education intervention improve health behaviors among Native American community members?” Among the intervention are 24-h of a site-specific (tailored), Native American Navigator/Community Educator-implemented cancer education program that addresses the full continuum of cancer care and increases the visibility of local patient navigators.

There are three phases to the study: phase I (planning, year 01); phase II (implementation, years 02–04); and phase III (evaluation, years 01–05). The study population for this project includes a total of 200 unduplicated Native Americans from each of the three original sites (i.e., CO, MI, and SD) and 150 from the two additional sites (total study n=900). The majority (85%) of participants in the study are Native American with the remaining 15% of other racial groups and ethnicities (including Latinos). All are 18 years of age or older. The majority are expected to be under-/uninsured (i.e., Indian Health Service is not “insurance”) and about 75% are women. The community participants include urban, rural, and reservation-based community members as well as Native Americans diagnosed with cancer and other Natives who have disabilities.

Each partner (ITCMI, NACR, and RCRH/GPTCHB) recruits two local natives for roles as paid patient navigators. The education level varies among sites, ranging from high school graduates to masters levels. However, all navigators are locally recognized as respected community members. Each navigator receives more than 125 h of training as well as at least semi-annual updates and refreshers. Table 1 summarizes some of the training topics.

Table 1.

Excerpt from navigation in-service training topics

| Topic | Approximate time |

|---|---|

| Overview of the study | 3 |

| NIH protection of human subjects (online training) | 3 |

| Confidentiality | 3 |

| HIPAA (provided by local healthcare clinics) | 6 |

| Overview of navigation programs | 3 |

| Audience response system (ARS) evaluation | 3 |

| Presentation skills | 3 |

| Online evaluation program | 6 |

| Healthy eating | 6 |

| Energy balance | 6 |

| Reducing exposure to environmental contamination | 3 |

| Cancer 100 Overview | 3 |

| “Get on the path to breast health” | 6 |

| “Get on the path to cervix health” (includes HPV vaccines) | 6 |

| “Get on the path to colon health” | 6 |

| “Get on the path to lung health” | 6 |

| “Get on the path to prostate health” | 6 |

| Navigating the local healthcare system | 3 |

| Cancer 101 diagnoses and tests | 3 |

| Cancer 102 treatment, managing side effects | 3 |

| “Native American Cancer Education for Survivors” (NACES) quality of life | 3 |

| Clinical trials | 3 |

| Survivors support circles | 3 |

| Palliative care for the native cancer patient | 3 |

| Supporting the family caregiver | 3 |

| Advanced directives, wills | 3 |

| Hospice care (benefits, limitations, choices) | 3 |

| “~20 hours for additional topics as requested by navigators or staff = 125+ | 108 |

Memoranda of Agreement—Organizations

The partners include agreements with up to two other Native American organizations each year. Each local, Native Memorandum of Agreement Organization has strong relationships with local American Indians. These local groups do not have to be the same organization(s) each year of the intervention. These organizations have specific tasks and deliverables to their respective local NNACC partners (see Table 2). Examples of such organizations during 2010 included Sioux Tribal College for GBTCHB, Mount Pleasant MI Program for ITCMI, and the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless for NACR.

Table 2.

Responsibilities of the Memoranda of Agreement Native Organizations

| Tasks | Deliverable |

|---|---|

| Coordinate the logistics for 24 h of AI community education workshops on the Cancer Continuum | Schedule dates, times, locations, and topics |

| Coordinate the logistics for family events to occur prior to (baseline) and about 3 months after each workshop series is completed (all participants invited) (total 2 family events with 2 Memoranda Native Organizations/ year) | Schedule dates, times, and locations for family events Track ARS keypad numbers used |

| Promote the workshop series to members or frequent users of the Memoranda Native Organizations | Copies/tracking of announcements to promotes the family events and workshops |

| Recruit at least 35 unduplicated AI community members to each workshop series (same and new participants for each workshop); retain and update a listing of all participants’ and the specific ARS keypad used by each | Submit to partner (originator of agreement) a list of keypads with names removed to document number of participants at each workshop |

| Host the educational sessions (note: navigators conduct and evaluate the workshops) | Submit copy of agenda (the navigators confirm participants via the anonymous ARS data) |

| Host 2 family events each year (1 baseline and 1 3-monthly 24-h workshop series is complete; the same numbered ARS keypads are distributed to each previous participant of any workshop) | Copy of agenda and keypad list of who attended the family event submitted to partner |

| Prepare and share easy-to-understand findings with those who took part in any workshop program | Copies of press releases, fliers or other products submitted to partner |

Native American Community Workshops

Each Memorandum Native Organization organizes at least one series of 24-h of community education workshops per year. The 24-h series includes workshops from four categories: prevention, early detection, quality of life/survivorship, and palliation (see Table 3). Each workshop averages 2 h duration and includes data collection (demographics, pre- and post-workshop knowledge, and overall workshop evaluation), content, and interactive activities (i.e., to reinforce knowledge presented using games and group activities). In collaboration with the local Native Patient Navigator, the Memorandum Native Organization selects workshop topics of interest from each of the four categories. These categories address the full continuum of cancer and allow the Memorandum Native Organization to tailor the topics to their local community members. PDF versions of the workshop slides are available at http://www.NatAmCancer.org under “handouts” tab upper right-hand side of the opening page.

Table 3.

Twenty-four hours of community education workshops (implemented by the navigators)

Category A: prevention

|

Category B: early detection

|

Category C: quality of life/survivorship

|

Category D: palliative care and end-of-life

|

The Navigators implement and evaluate the workshops, while the Memorandum Native Organizations coordinate logistics, host the family events, and keep track of participants’ keypad numbers for each session. Participants who complete a workshop receive a gift card of $5 or $10 (varies by partners’ sites) per session. An anonymous audience response system (ARS) is used to collect demographic data and ask opinion items. Additionally, pre- and post-session knowledge questions are asked that allow for tracking improvements in participant knowledge throughout the intervention.

American Indian Family Fun Events

Family fun events are used to initiate the series of workshops and to wrap up and evaluate the series 3 months following their completion. The initial family event is the “Baseline” (kick-off). The Memorandum Native Organization invites local family and community members for a fun activity that includes healthy food and about 30 min of navigator-provided instruction (15 min for project overview, explanation of the upcoming 24-h of community workshops, and dissemination of the project information sheet another 15 min to collect demographic and pre-intervention knowledge and behavioral items using the ARS). These events may include health fairs, bingo games, and outdoor picnics.

The post-family fun event is held 3 months following the completion of the 24-h series of workshops. The Memorandum Native Organization coordinates the logistics and documents distribution of keypads to designated users (participants use the same keypad for baseline family event, the 24-h of workshops and the 3-month delayed family event). Twenty to 30 min of the event is allocated for the Navigator to share results from the 24 h of workshops and to collect demographics and delayed evaluation knowledge items.

Evaluation

Community education slides and ARS evaluation items are approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (IRB). The Navigators collect ARS data (demographics, pre- and post-workshop knowledge, embedded opinion items, and workshop evaluation) during the 24-h of community education and at both of the family events. Following each session/family event, the Navigators upload their workshop evaluation data to the online evaluation program (see separate article this issue of JCE for description of the online evaluation program). The Navigators meet with their local supervisors for debriefing during and following each 24-h series.

Outcomes

To date, NNACC has several outcomes. The first is the development of site-specific (tailored), Native American Navigator-implemented cancer education programs that address the full continuum of cancer care with participants in these programs is averaging a >25% increase from pre- to post-workshop knowledge evaluation in each setting. As a result of these workshops, increased help in scheduling and completing cancer screening or diagnostic appointments was requested by workshop participants of the Navigators. Thus, the Navigators’ visibility and skills are greatly increased by the series of 24-h workshops. This resulted in patients with cancer receiving improvements in timeliness and quality of care. Although the education intervention is designed for implementation over 3 years, by intervention year 2 the full number of unduplicated participants took part. This required a modification in the study protocol to WIRB to allow the study to include more participants (approved fall 2010).

Lessons Learned During the Initial 2.5 Years of the NNACC

Lesson 1. Shortened Start-up and IRB Issues

Year 01 was shortened to 7 months; this was a mixed blessing. While excited to begin the project, the three original project partners needed the full 12 months to hire Navigators, organize community workshop education materials, obtain Western IRB (WIRB) approvals for the overall project, and local IRBs for designated sites and to refine the evaluation items. The project staff managed to comply with deadlines, but it was a very stressful period. The WIRB required all American Indian Community Power Point® education slides and ARS items for initial approval. The project partners were planning to submit the Navigator In-service Training materials for approval first. WIRB was focused on community workshop, summary information sheets, evaluation, and any information disseminated to community members. They reviewed more than 358 Power Point® slides and 50 ARS items.

Due to local tribal policies, South Dakota (SD) had to include two local IRBs (one hospital and one tribal) in addition to the national approvals from the WIRB. One local IRB took more than 9 months to approve the intervention protocols and products while the other sites were able to start their interventions. The advantage was that SD was able to benefit from its partners’ initial efforts, issues, challenges encountered by the other two sites. But the delay resulted in these South Dakota partners feeling the stress of possibly falling behind. Because of their dedication and once local tribal IRBs were obtained, they quickly “caught up” with the other two sites.

Lesson 2. Costs for Face-to-Face Navigator Training were More Than was in the Budget

The start-up time to prepare and train Navigators took longer than was anticipated, requiring 6 months rather than 4 months. All partners shared in the education. A variety of methods were used: presentations, workshops, and trainings. “Presentations” are primarily a one-way session with about one-quarter of the time for question and answer, thus limiting participant interaction. “Workshops” require pre-and post-knowledge assessment and satisfaction assessments and may also include assessing attitudes, behaviors, etc. They include an interactive activity to allow participants to practice the behavior specified in the objectives. “Trainings” include every component of a workshop, but also include observational role playing, case studies, and tasks that require increased skills development. The Navigators take part in workshops, but also must complete many hours of trainings to demonstrate skills. Some of these can be done via webinar (such as many of the workshop presentation skills), but others cannot (assembling and correctly using the ARS equipment).

The protocol for CBPR requires that 25% of funds are allocated for administrative tasks such as creating the programming for the online evaluation program, completing all applications and requirements for WIRB, and creating most of the training for the Navigators. The remaining money is split equally among the sites for implementation of the intervention. Because there were three sites, monies were limited. The original plan was to hold three face-to-face trainings with the remaining trainings conducted via conference call and webinar. However, the NCMHD awarded a supplemental grant to implement a series of four seminars around the country that addressed the full continuum of cancer. These seminars allowed the Navigators more face-to-face training sessions; however, due to the number of possible topics to be covered, the Navigators wanted more face-to-face sessions. The conference calls and webinars provided a good backup, but time was still needed for supervisors and administrative staff to observe the Navigators role playing certain situations to confirm new skills attainment.

Lesson 3. Staff Turnover and Videos to Assist In-service and Peer Training of Navigators

One site had high staff-turnover affecting the training and preparation of the Navigator. However, because NACR staff had filmed the faculty during the seminars and most of the face-to-face trainings, these DVDs quickly allowed newly hired staff to be trained and become familiar with the cancer education content. The other Navigators from the same regions were essential in augmenting the videos with peer education and training. Conference calls with webinars were very effective trainings with Navigators practicing teaching their lessons via webinar from Sault Saint Marie, Michigan to Rapid City, South Dakota and to Pine, Colorado. The two observing sites role played community members to help the Navigator practice answering questions and responding to comments.

Lesson 4. Creating the Education Intervention Took Longer to Refine than was Anticipated

The partners discussed topics for workshops that addressed the full continuum of cancer. Existing Power Point® slides, primarily from NACR and GPTCHB provided the foundation. After the initial 24-h of workshops were completed, the partners identified many refinements that were needed for Power Point® slides. Some slide sets were incomplete. Thus, they were refined to include: learner objectives, notes pages for the navigators, interactive activity, and the ARS items (demographics, pre- and post-workshop knowledge, opinion items, and workshop evaluations). None of the original slide sets included all of these components and missing segments were added to each of the topics. All revisions were submitted to the WIRB for approval August 2010.

Lesson 5. Memorandum Native Organization and Participant Accountability

Another lesson was to include more specifics about the Memorandum Native Organizations duties and deliverables (see table 2). This was primarily due to one Memorandum Native Organization during the first year of the education intervention. It was not fully prepared to staff all events, requiring Navigators to help out rather than doing required activities to prepare for presentations and evaluations. Helping the Memorandum Native Organizations with workshop registration and tracking ARS keypads interfered with efficient start-up times for some workshops. Improving the language for the deliverables helped eliminate this issue. In addition, payment to each Memorandum Native Organization was disseminated in three to four segments rather than in one or two lump sums. This allowed for start-up monies to provide the baseline family event, monies for the workshop series divided into two portions and the fourth payment following the 3-month post-family event. Generating the list of specific deliverables (Table 2) greatly reduced these issues and prevented similar challenges with other Memorandum Native Organizations.

Some community participants showed up late to workshops; some 15 min late, but others as late at 80 min. In collaboration with the Memorandum Native Organizations, a policy was developed that only those who arrived in time to take part in the initial ARS questions would be eligible to receive a gift card for workshop participation (i.e., they had to be in attendance within 15 min of starting the workshops).

Lesson 6. Online Evaluation Limitations and Benefits

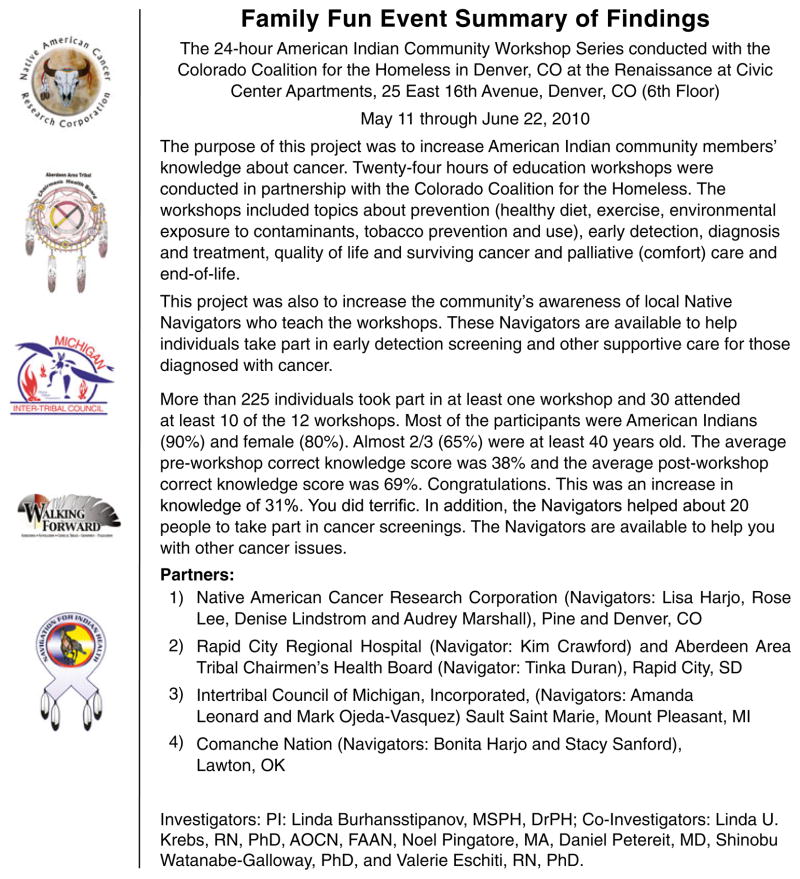

This evaluation program is described in detail in another article within this journal. Initially, the highly technical online evaluation system was unable to produce reports that would assist the Navigators in sharing local findings with Memorandum Native Organizations for the 3-month post-family event. Likewise, the initial limitations prohibited rapid response to the NNACC funder, NIH National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities. In addition, the WIRB requested examples of summary reports from the online evaluation program to ascertain that there were no identifiable data being released. In summer/fall 2010, new programming was developed to make online evaluation reports accessible to all partners. Most importantly, the reports can be tailored (see Fig. 2) to share results with the community participants and the Memorandum Native Organizations.

Fig. 2.

Examples of tailored summaries for community partners and participants

Lesson 7. Storing WIRB-Approved Education and ARS Slides

The NNACC partners experienced another technical difficulty. Initially, the NNACC partners purchased Sharepoint© online data storage service for NNACC draft slides, evaluations items, and other materials. However, the space was too limited and the entire curriculum could not fit. Likewise, it was tedious to remove files that were outdated from the Sharepoint© site, leaving multiple versions of a presentation on the site and resulting in outdated versions being used. To address this, NACR’s web designer added a new private, password-protected page for all NNACC partners and the entire curricula and related materials (e.g., NNACC partners created interactive participant games like teepee question game and coyote-bear) are based there.

Lesson 8. Repeat Participation

An unexpected outcome was that many community members attend subsequent workshop series after the initial 24-h series was completed. Some said they missed a specific workshop during the first series or wanted to repeat a specific workshop. Others attended because they brought other family members or friends to the workshops and were there to reinforce their attendance. The project staff wanted to see if there was a dose–response factor affecting the increased knowledge of the participants. They anticipated a small number of community members attending eight or more of the sessions (most series have 12 2-h sessions) with the majority attending three or fewer sessions. However, most but not all of the NNACC sites are experiencing a different situation; many of the participants who attended a majority of the workshop series also attended the next one. Because the goals of the study are to only count unduplicated participants, these individuals’ keypad numbers needed to be removed from the preliminary evaluations and data analyses. In addition, these participants often are very helpful with workshop logistics such as helping distribute handouts and collecting keypads and invite family and friends to join them for the workshops. Overall, they have fun and reinforce their learning with the second workshop series.

This was unexpected and led to two problems: (a) having more participants take part in the study than was within the initial WIRB study protocol and (b) insufficient gift cards within the intervention budgets for these participants. Partners requested WIRB approval for an increased sample size and also had to request funding from other sources to provide gift cards for the repeaters as well as the additional people attending the workshops.

Lesson 9. Community Interest in Education

A very positive lesson was learning how eager the community is for education workshops on cancer such as those provided through NNACC. They ask good questions of the speakers and many ask to repeat the same workshop(s). The workshops are fun, productive, interactive, and effective. An informal survey of participants from one of the Michigan sites asked the participants to report actions taken as a result of the classes. Of those who completed the survey: 44% indicated they shared information with a friend or family member; 44% made changes in their own lifestyle; and 22% urged others to get cancer screening or other health-related services. This information indicates that our project is on track for reaching its goal and is valuable to the local communities.

Lesson 10. Audience Response System

The audience response system took time for the Navigators to learn, but now is working out well for all sites. New ARS skills are shared with one another through in-service training and peer education. For example, one Navigator supervisor learned how to use “participant” keypad lists that helps track use of the same keypad for a single participant throughout the two family events and the series of the 24-h of workshops. This skill was shared with all others during both face-to-face semi-annual meetings and via a webinar. This participant list greatly simplifies the tracking and documentation of unduplicated participants. The partners also share their keypads with one another for large events. For example, the unveiling of the “Rollin’ Colon” by Ms. Duran in South Dakota had many more participants than she had of keypads. NACR sent her 50 more for the event. Sharing resources is among the desired outcomes of CBPR studies.

Summary

The NNACC partners collaboratively addressed multiple limitations and challenges, primarily during the initial 2 years of the education intervention within the study. The 24-h series of workshops is resulting in significant increases in community members’ knowledge (>25%) and likewise is successfully increasing interactions with the Native Navigators to help schedule screening or cancer care appointments. The Memorandum Native Organizations are proving to be very strong, collaborative partnerships within each of the local settings. The community enjoys the workshops and several bring others with them to the workshops as well as those who repeat taking part in workshops at other locations when feasible (i.e., driving distances). The IRB processes required both regional and national approvals and took more than 9 months for the initial study approval which is not unusual with Native American studies. The Navigators completed 125 h of training and took part in refresher and updated sessions through face-to-face and webinars. Both formats work but the face-to-face is preferred by all, but is more costly. All of the workshop slides were missing some components (objectives, notes pages, interactive activity, and ARS items) and all needed refinements and expansion to include all workshop components. The specifics for the Memorandum Native Organization deliverables needed more details and refinements and resulted in increased efficiency and local collaborative partnerships. As of February 2011, the partners have collaborated with ten Memorandum Native Organizations and only one was slack in carrying out its NNACC responsibilities. The ARS required additional training sessions and had a definite learning curve for the Navigators, but once learned they use the ARS well and actively participate in peer education with one another. The online evaluation program was not intuitive and was difficult to effectively use. This was resolved by adding functions that allowed each partner to tailor reports. Thus, GPTCHB was able to produce the summary report for Sioux Tribal College participants, ITCMI produced the summary for the Mount Pleasant MI Program. Adding these functions to the NNACC partners’ databases resulted in simplified, tailored reports for each workshop series. Use of the NACR website for a password-protected page to store all NNACC workshop and training materials was easier to manage than was the use of other online storage programs. The community interest in taking part in the workshops was greater than what was anticipated and several participants are attending more than one workshop series when transportation and other logistical issues are addressed. All of the Navigators’ presentations skills are improving and all are enjoying implementing the workshops and family events.

Conclusions

Navigation studies and programs are increasing throughout the USA. However, many community members are unaware of their existence or where they are located and they may be underutilized by those who need the navigation services the most. By adding the series of 24-h of community workshops, the NNACC partners greatly increased the Navigators’ visibility and accessibility. Other programs may also benefit similarly by adding community education events implemented by the Navigators.

Likewise, the partnering with local Memorandum Native Organizations was very successful for nine out of ten education series to date. The advantages build upon the Memorandum Native Organizations’ existing Native community activities and participants. Thus, the Memorandum Native Organizations usually have a local newsletter to their constituents and they can add in the announcements for the upcoming family events and series of 24-h of workshops. These organizations also receive a $4,000 fee to implement their NNACC tasks (Table 2) and the monetary support is greatly appreciated by these Native organizations. This collaboration also improves the working relationships with the respective NNACC partner (e.g., Lakota Tribal College and GBTCHB; Mount Pleasant MI Program and ITCMI, Colorado Coalition for the Homeless and NACR). Other programs, regardless of race or ethnicity could integrate such collaborations within their own Navigation programs.

Cancer education interventions can be fun and productive for both the workshop facilitators (navigators) and community participants. The NNACC receives such praise from both its staff and community members:

Navigator: This is the first time I’ve been part of a research study. I did not know they could be so much fun. I know that I am providing both education and access to services to my community and they really need both. I love this work.

Navigator: The community is so wonderful to work with. They love the workshops, even though we address some very distressing topics, like cancer and end-of-life. They ask for more workshops and want to know when the next series is going to begin so that they can bring their family and friends.

Navigator coordinator: I am so impressed with the increased number of community members who now seek out our 2 Navigators for help with their cancer care. We know the Navigators are helping the community members get access to timely and quality cancer services. This means higher quality and quantity of life for our communities. This is a great program and we need similar programs to address other Native priorities, like diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and methamphetamine issues.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Native Navigators and the Cancer Continuum (NNACC) [PI: Burhansstipanov, R24MD002811] and the Native Navigation across the Cancer Continuum in Comanche Nation (NNACC-CN) [PI: Eschiti, R15 NR 012195]. The project described was supported by Award Number R15NR012195 from the National Institute of Nursing Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official vies of the national Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health. This study would not be possible without the dedication and efficiency of each sites’ patient navigators: Colorado/NACR (Lisa Harjo, MS, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma; Audrey Marshall, Oneida; and Rose Lee, BS, Navajo Nation); Michigan/ITCMI (Amanda Leonard and Mark Ojeda-Vasquez); South Dakota/RCRH/GPTCHB (Tinka Duran and Kim Crawford); and Comanche Nation (Leslie Weryackwe and Stacy Weryackwe-Sanford LPN).

Western Institutional Review Board Protocol Number: 20081858

Abbreviations

- ARS

Audience response system (collects demographic/evaluation data electronically)

- CBPR

Community-based participatory research

- GPTCHB

Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Health Board

- ITCMI

Intertribal Council of Michigan, Incorporated

- NNACC

Native Navigators and the Cancer Continuum

- NACR

Native American Cancer Research Corporation

- RCRH

Rapid City Regional Hospital

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Linda Burhansstipanov, Email: LindaB@NatAmCancer.net, Native American Cancer Research Corporation (NACR), 3022 South Nova Road, Pine, CO 80470-7830, USA.

Linda U. Krebs, Email: Linda.krebs@ucdenver.edu, College of Nursing, University of Colorado Denver, ED2N Room 4209, 13120 East 19th Avenue, P.O. Box 6511, Aurora, CO 80045, USA

Shinobu Watanabe-Galloway, Email: swatanabe@unmc.edu, Epidemiology Department, College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4395, USA.

Daniel G. Petereit, Email: DPetereit@rcrh.org, Department of Radiology Oncology, Rapid City Regional Hospital, John T. Vucurevich Cancer, 353 Fairmont Blvd, Rapid City, SD 57701, USA

Noel L. Pingatore, Email: noelp@itcmi.org, Inter-Tribal Council of Michigan, Inc., 2956 Ashmun St., Sault Ste. Marie, MI 49783, USA

Valerie Eschiti, Email: valerie-eschiti@ouhsc.edu, OUHSC College of Nursing, 1100 North Stonewall Ave, CNB 453, Oklahoma City, OK 73117, USA.

References

- 1.Burhansstipanov L, Bad Wound D, Capelouto N, Goldfarb F, Harjo L, Hatathlie L, Vigil G, White M. Culturally relevant “navigator” patient support: the native sisters. Cancer Pract. 1998;6(3):191–194. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.1998.006003191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burhansstipanov L, Dignan MB, Bad Wound D, Tenney M, Vigil G. Native American recruitment into breast cancer screening: the NAWWA project. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15:29–33. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burhansstipanov L. Native American community-based cancer projects: theory versus reality. Cancer Control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 1999;6(6):620–626. doi: 10.1177/107327489900600618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dignan MB, Burhansstipanov L, Hariton J, Harjo L, Rattler T, Lee R, Mason M. A comparison of two Native American Navigator formats: face-to-face and telephone. Cancer control: Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2005:28–33. doi: 10.1177/1073274805012004S05. Grant [NCI R25 CA77665] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burhansstipanov L, Dignan MB, Schumacher A, Krebs LU, Alfonsi G, Apodaca C. Breast screening navigator programs within three settings that assist underserved women. J Cancer Educ. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0071-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burhansstipanov L, Krebs LU, Seals BF, Bradley AA, Kaur JS, Iron P, Dignan MB, Thiel C, Gamito E. Native American breast cancer survivors’ physical conditions and quality of life. Cancer. 2010 doi: 10.1002/cncr.24924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]