Abstract

The present study examined 12-month prospective relations among trait self-control, subjective role investment, and alcohol consumption in a sample of university students (N = 129). Using neo-socioanalytic theory and the social investment hypothesis as guiding frameworks, it was expected that greater initial role investment would predict greater self-control and less alcohol consumption at follow-up. Path analyses showed higher initial levels of subjective college student role investment predicted greater subsequent self-control and lower drinking amounts, controlling for initial standing on self-control and alcohol consumption. Greater initial trait self-control also predicted subsequent lower alcohol consumption. The discussion emphasizes the importance of incorporating subjective role investment, in addition to nominal role participation, in developmental accounts of personality traits, social identity, and behavior.

Keywords: Social investment, self-control, role, alcohol, college, development

1. Introduction

The experience of college life is commonly thought to represent a dynamic and multifaceted developmental phase wherein individuals transition from the lingering immaturity of adolescence to the burgeoning maturity of young adulthood. This lay perspective is supported by research showing increases in aspects of personality that are considered markers of psychological maturity during late adolescence and young adulthood, including the Big Five traits of agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness (Lüdtke et al., 2011; Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006). The patterning of these developmental trends is often attributed to the influences of normative social roles (Roberts, Wood, & Caspi, 2008). In particular, the social investment hypothesis is posited as a means of explaining trends in personality trait development across the lifespan, but especially during young adulthood (Roberts & Wood, 2006; Roberts, Wood, & Smith, 2005).

Normative social investment is defined as involvement and commitment to age-graded or adult social roles, including those related to work or career (college student, employee, etc.), family (romantic partner, parent, etc.), and community (volunteer, religious adherent, etc.). Engagement in such roles is expected in late adolescence and young adulthood and premature or delayed entry into these domains could be considered non-normative (Helson, et al., 2002; Helson, Mitchell, & Moane, 1984; Neugarten, Moore, & Lowe, 1965; Roberts et al., 2005). In this way, role participation represents a central feature in the development of psychological maturity.

However, in the case of college students (or any role-defined group), role participation alone cannot offer an explanatory account of trends or predictive patterns in traits due to its invariance (that is, college students, by definition, are participating in that role). The assessment of categorical role participation (e.g., student, not student) potentially misses important individual differences in the amount and process of commitment within a given social identity. As a result, an account of subjective role investment becomes critical to an understanding of the relationship between normative role involvement and standing on traits related to psychological development and maturity. The present study uses this insight to examine short-term longitudinal relations among subjective role investment, the self-control facet of conscientiousness, and alcohol consumption – a behavior with close ties to the broader maturity-related phenotype of constraint/disinhibition (Bogg & Finn, 2010; Carver, 2005; Clark & Watson, 1999, Hampson, 2012; Rothbart, 2011).

1.1. Subjective college student role investment’s relations to trait self-control and alcohol consumption

To date, there is little direct evidence linking investment (not simply participation) in the college student role (i.e., how involved, absorbed, or responsible a college student feels toward that role) with conscientiousness-related traits, such as self-control, or disinhibited behaviors, such as excessive alcohol consumption. Much of the research on trait development in late adolescence and young adulthood includes assessment points before or after entry into the college student role or, more specifically, does not measure subjective college student role investment. For example, in a large sample of German students,Lüdtke et al. (2011) showed continued participation in the college student role was associated with an increase in conscientiousness over a four-year period that bridged high school to college. Similar results have been found for other late adolescent or young adult samples that included assessment points which occurred before, during, or after the college years, but were not focused on how investment in the college student role might be related to trait development (e.g., Donnellan, Conger, & Burzette, 2007; Vaidya et al., 2008). These results are intriguing and important because they are suggestive of the influence of college student role investment, but such an effect can only be inferred given the study designs.

As with its relations to trait development in young adulthood, subjective educational investment has not been a focus of inquiry in relation to alcohol consumption. However, the related construct of studying expectancies was examined in a sample of college students (Levy & Earleywine, 2003). Studying expectancies were measured as beliefs about “the potential personal gain inherent in studying, earning a college degree, and maintaining a high GPA” (p. 553). The results showed that, among students with higher positive alcohol expectancies, those students who also had higher studying expectancies drank less alcohol and had significantly fewer drinking-related problems than students who had lower studying expectancies. Similarly, in a sample of college students with a heterogeneous prevalence of excessive alcohol consumption, Bogg (2011) found greater subjective educational investment to be associated with lower two-week quantity, frequency, and duration of alcohol consumption. Taken together, these two studies provide evidence for a possible constraining influence of college student role investment as it relates to patterns of alcohol consumption.

1.2. The present study: Hierarchical and temporal relations among role investment, traits, and disinhibited behaviors

For the model of the relations among the study constructs, we adopted a neo-socioanalytic organization (cf., Bogg, 2008; Bogg et al., 2008), arranging them from more general and consistent measures of the self (i.e., trait self-control) to more specific and discrete measures of behavior (i.e., alcohol consumption), with subjective college student role investment occupying an intermediate space. While this arrangement is amenable to the constructs of the current study, it is intended to be generic in its application to analogous forms of subjective role investment, relevant traits, and related behaviors. For example, the model could be used to test relations among parental role investment, the conscientiousness-related facet of reliability, and financial management.

Evidence of the social investment hypothesis is posited to be found in two prospective pathways; a positive predictive pathway from subjective college student role investment to trait self-control and a negative predictive pathway from subjective college student role investment to alcohol consumption. This is expected under the social investment hypothesis because the process of role commitment is “thought to exact a form of social control through the role demands embedded in these contexts that call on individuals to act with more responsibility and probity” (Roberts & Caspi, 2003; p. 203). Therefore, after controlling for initial levels of trait self-control and alcohol consumption, higher initial levels of subjective college student role investment should be associated with higher levels of trait self-control and lower levels of alcohol consumption 12 months later. Moreover, a broad swath of cross-sectional research has established relations between traits related to self-control and alcohol consumption in late adolescent and young adult samples (Bogg & Roberts, 2004). Recently, these findings have been extended to show how trait impulsivity (the inverse of trait self-control) is associated with higher levels of problematic alcohol involvement in short-term follow-up assessments in a college-aged sample (Littlefield, Sher, & Wood, 2009). As a result, it is expected that higher initial levels of trait self-control should predict lower levels of alcohol consumption 12 months later.

In addition to the two social investment pathways and the trait-behavior pathway, three other path pairings allow for an examination of transactional relationships. These include investment-trait transactions between subjective college student role investment and self-control, investment-behavior transactions between subjective college student role investment and alcohol consumption, and trait-behavior transactions between self-control and alcohol consumption.

While the present investigation is primarily focused on subjective college student role investment, two other domains of subjective investment – family of origin and friends – also will be examined using the model described above. These domains were chosen for their ubiquitous representation in the sample – all participants reported having family and friends. Similar to subjective college student role investment, it is expected that the influence of investment in and commitment to family and friends will be normative, with higher initial levels of investment predicting higher levels of trait self-control and lower levels of alcohol consumption 12 months later.

Finally, recent research findings and contemporary models of the role of alcohol consumption in adolescence suggest age of first drink is not only an important risk factor for future alcohol abuse and dependence, but also a general risk factor for deleterious development of self-regulation and the adoption and maintenance of social roles (Brown et al., 2008; Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006). As such, we examine the role of age of first drink as a background predictor of initial standing on subjective role investment, trait self-control, and alcohol consumption.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The recruitment goal was to acquire a sample of 18–23-year-old students from Indiana University that varied in its expression of disinhibited tendencies and alcohol consumption. Among college students, one of the most prevalent disinhibitory problems is excessive alcohol use (Hingson et al., 2005). As a result, study advertisements (flyers posted around the university, including residence halls, advertisements placed in the student newspaper, and postings to a Web-based university classified advertisement system) targeted a range of disinhibited tendencies and alcohol consumption behaviors (e.g., “adventurous” and “impulsive,” versus “introverted” and “reserved”; “drink modest amounts of alcohol and who do not take drugs” versus “heavy drinker”). This approach is effective in recruiting participants that vary in disinhibited tendencies and alcohol use (Bauer & Hesselbrock, 1993; Finn et al., 2002). Participants were excluded if they [1] were not between 18 and 23 years of age, [2] could not read and/or speak English, [3] had never consumed alcohol, [4] reported any serious head injuries, [5] had a history of psychosis, and [6] were not enrolled in post-secondary coursework (i.e., university classes).

At the beginning of an assessment session, participants reported alcohol and drug use in the past 12 hours, the number of hours of sleep during the previous night, the most recent meal, and were given a breath alcohol test using an AlcoSensor IV (Intoximeters, Inc., St. Louis, MO). Participants were rescheduled if their breath alcohol level was greater than 0.000%, if they consumed any drug within the past 12 hours, if they felt hung-over, or if they reported or appeared to be impaired, high, overly sleepy, or if they were unable to answer questions. All participants were paid $10/hour plus a $5 on-time bonus.

At Time 1, the sample (N = 159) was sex-balanced (54.1 % women) and mostly European-American/Caucasian (77.4 %), with a mean age of 20.17 years (SD = 1.37 years). Three strategies were used to help manage attrition across the two waves. The first strategy screened participants for study inclusion based on their planned availability for follow-up assessment. Only students that indicated availability for the complete timeline of the project were allowed to participate. The second strategy requested participants to provide their full names, local and permanent mailing addresses, primary and secondary telephone numbers and email addresses. This strategy also requested participants to provide contact information (full names, local mailing addresses, primary and secondary telephone numbers and email addresses) for three close associates (e.g., friends, family, employers) who might know how to contact the participant if research staff were unable to contact the participants directly with the information they provided. The third strategy was to incorporate a $10 follow-up assessment bonus (in addition to the on-time bonus and $10/hour rate), about which participants were notified at the first session.

Using these strategies, 81.3 % of the sample (n = 129) was reacquired at Time 2. Compared to participants assessed at Time 2, those who were not assessed (n = 30) did not show substantial differences on age (M = 20.87 years), sex (60 % women, n = 18), or ethnicity (70% European-American/Caucasian). In spite of the demographic similarities, the missing participants’ data were not retained for the analyses due to the uncertainty regarding their subsequent college student. In a study examining college student role investment, we felt it necessary to exclude data from participants whose Time 2 status as students could not (because of missing data) be verified.1

The complete sample (N = 129; across Time 1 and Time 2) was sex-balanced (53.5 % women) and mostly European-American/Caucasian (78.3 %), with a mean age of 20.00 years (SD = 1.36 years). Consistent with the recruitment goal of producing a sample with a range of disinhibited tendencies, 42.3 % of the complete sample (25 men, 30 women) met lifetime diagnostic criteria for alcohol dependence using the Semi-Structured Assessment for the Genetics of Alcoholism (SSAGA; Bucholz et al., 1994) which uses criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

2.2. Assessment materials

2.2.1. Subjective college student, family, and friend role investment

Subjective college student, family, and friend role investment was assessed with one item adapted from a measure of family involvement (Misra, Ghosh, & Kanungo, 1990) and two items developed by Lodi-Smith (2007). Participants were instructed to indicate their “level of agreement with the items related to the importance of the various life domains.” The three-item subjective college student role scale assessed involvement in education and the student role (e.g., “I like to be absorbed in school most of the time,” “I am very much involved personally in my schooling/education,” “I feel a strong sense of responsibility for my education”) using a five-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly disagree, 5 = Strongly agree; Time 1 α = .67, Time 2 α = .75). Family of origin investment (parents, siblings, and extended family members) was assessed with three parallel items (e.g., “I feel a sense of responsibility for my family”; Time 1 α = .82, Time 2 α = .87). Friend investment also was assessed with three parallel items (Time 1 α = .71, Time 2 α = .78).

2.2.2. Trait self-control

The Control subscale of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) was used to assess self-control (Tellegen, 1982). The MPQ control scale is comprised of 24 items (e.g., “When faced with a decision I usually take time to consider and weigh all aspects.”) using a dichotomous response scale (i.e., “true” or “false”; Time 1 α = .92, Time 2 α = .93).

2.2.1. Alcohol consumption and age of first drink

Alcohol consumption was assessed by combining two measures. Typical weekly alcohol consumption was determined using an interview during which the participant reported the typical number and type of alcoholic drinks consumed each day of the week over the past three months. Typical was defined as being “more than half of the [day of week] over the past three months.” Past week consumption was assessed using an interview where participants reported whether they consumed alcohol for each day of the past week and, if so, the amount they consumed. A composite score of alcohol consumption was created by summing the typical weekly alcohol consumption and past week alcohol consumption scores.

To provide an account of the effect of age of first drink on trait self-control, subjective role investment, and alcohol consumption, age of first drink (“How old were you the first time you drank more than just a sip of alcohol?”) was assessed as a Time 1 background/control variable.

2.3. Analyses

Correlational analyses were first used to examine the magnitude of the relationships among the measures of subjective investment, MPQ control, and alcohol consumption within and between Time 1 and Time 2. We then used Kenny’s (1975) reliability ratios method to test for changes in the magnitude of cross-lag correlations that are attributable to fluctuations in reliability. As Kenny (1975) states, “with the reliability ratios the cross-lagged correlations can be corrected for changes in reliability in a way similar to correcting a correlation for attenuation” (p. 898).

Longitudinal path analyses were then constructed and analyzed (using Amos 20). Correlated errors at Time 1, cross-time autopaths, and all cross-lagged paths were tested in the full model. Next, we used Campbell and Kenny’s (1999) time-reversed analysis to examine whether the temporal ordering of the variables is necessary for the model to hold. Campbell and Kenny argue that cross-lagged paths should only be significant in the time-forward direction. If the cross-lagged paths are maintained in a time-reversed analysis, then regression artifacts may be accounting for the observed pattern of effects in the time-forward model. Finally, age of first drink paths to Time 1 variables were included in the full model.

Model fit was determined through examination of the statistical significance of standardized path weights (i.e., p < .05), as well as through the Comparative Fit Index (CFI; Bentler, 1990). A CFI score above .90 suggests adequate fit.

3. Results

3.1. Time 1 and Time 2 correlations among social investment scales, MPQ control, alcohol consumption, year in school, age at Time 1, and age of first drink

Table 1 displays the correlations among the study variables. Consistent with the social investment hypothesis, higher subjective college student role investment was associated with higher MPQ control scores and lower alcohol consumption scores within and across time points. Subjective family role investment was not associated with MPQ control or alcohol consumption at either time point. Among the possible relations with subjective friend role investment, only higher alcohol consumption at Time 1 was associated with higher subjective friend role investment at Time 1 (r = .21, p < .05). Consistent with past research, higher Time 1 and Time 2 MPQ control scores were associated with lower Time 1 and Time 2 alcohol consumption scores (p < .05). Year in school and chronological age at Time 1 were not significantly associated with any of the study variables, showing older students in the 18– 23-year-old sample were not necessarily more self-controlled, invested, or drinking less than the younger students in the sample. Lower age of first drink was associated with higher subjective friend role investment at Time 1, as well as lower MPQ control and greater alcohol consumption at both time points (p < .05).

Table 1.

Time 1 and Time 2 correlations among subjective role investment scales, MPQ control scale, alcohol consumption, Time 1 age, year in school, and age of first drink

| College Role T1 |

College Role T2 |

Family Role T1 |

Family Role T2 |

Friend Role T1 |

Friend Role T2 |

MPQ Control T1 |

MPQ Control T2 |

Alcohol Quantity T1 |

Alcohol Quantity T2 |

Year in School |

Age at T1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| College Role T1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| College Role T2 | .62* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Family Role T1 | .12 | .02 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Family Role T2 | .06 | .24* | .48* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Friend Role T1 | .13 | .09 | .48* | .27* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Friend Role T2 | .03 | .14 | .29* | .57* | .54* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| MPQ Control T1 | .34* | .33* | −.12 | −.05 | −.02 | −.06 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| MPQ Control T2 | .42* | .38* | −.13 | −.03 | −.03 | −.04 | .85* | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Alcohol Quantity T1 | −.30* | −.19* | .16 | .01 | .21* | .08 | −.40* | −.39* | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Alcohol Quantity T2 | −.39* | −.31* | .12 | −.04 | .09 | .13 | −.46* | −.43* | .70* | -- | -- | -- |

| Year in School | .07 | −.07 | .04 | −.10 | .02 | −.06 | .07 | .08 | .07 | −.01 | -- | -- |

| Age at T1 | .02 | −.11 | .08 | −.04 | −.02 | −.11 | .04 | .05 | .14 | .03 | .88* | -- |

| sAge of first drink | .10 | .02 | −.16 | .02 | −.19* | −.04 | .35* | .24* | −.43* | −.36* | .13 | .14 |

| Mean | 3.94 | 3.95 | 4.15 | 4.10 | 4.11 | 4.09 | 14.84 | 15.14 | 25.50 | 25.92 | 2.2 | 20.00 |

| (SD) | (.71) | (.77) | (.73) | (.91) | (.68) | (.73) | (6.78) | (6.78) | (30.61) | (28.58) | (1.14) | (1.36) |

Note.

p < .05.

MPQ = Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Year in school is year in college past receipt of high school diploma (e.g., 1 = first year of college). Repeated measures analyses did not show significant differences between Time 1 and Time 2 variables (all ps > .05).

Kenny’s (1975) test for the effects of changes in reliability on the magnitude of the cross-lagged correlations showed only trivial differences between the observed correlations and the adjusted correlations (i.e., change in r no greater than .015 for all significant correlations). These results suggest the observed cross-lagged correlations do not fluctuate based on changes in reliability and that the differences in magnitude among the observed cross-lagged correlations are reliable. These trends hold when either the synchronous (within-time) correlations or Cronbach’s alphas are used to compute the reliability ratios that are then used in the computation of the correction.

3.2. Longitudinal path analyses

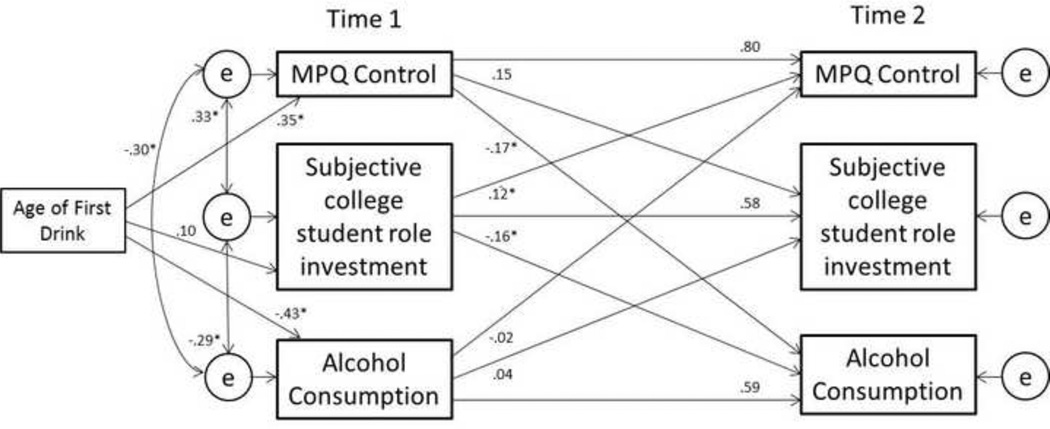

The initial full model without age of first drink [χ2(9, N = 129) = 38.98, p = .000, CFI = .92] provided support for the social investment hypothesis via significant (p < .05) Time 1 subjective college student role investment pathways to Time 2 MPQ control and Time 2 alcohol consumption. A significant path from Time 1 MPQ control to Time 2 alcohol consumption also was found. To test for the possibility of regression artifacts, we re-modeled the directionality of all paths from Time 2 to Time 1 (Campbell & Kenny, 1999). Of particular interest (based on significant time-forward paths), the time-reversed paths for subjective college student role investment (at Time 2) to MPQ control (at Time 1), subjective college student role investment (at Time 2) to alcohol consumption (at Time 1), and MPQ control (at Time 2) to alcohol consumption (at Time 1) were all non-significant (p > .05), with two of these paths changing signs as well. These results suggest the temporal ordering of the cross-lagged paths is meaningful and is not easily explained as a product of regression artifacts. Finally, we included age of first drink in the model as a predictor of the Time 1 variables, which improved model fit [χ2 (6, N = 129) = 6.20, p = .40, CFI = 1.00], and resulted in significant paths to MPQ control and alcohol consumption (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prospective longitudinal path analysis for MPQ control, subjective college student role investment, and alcohol consumption, *p < .05.

4. Discussion

The goal of the present study was to examine the social investment hypothesis using a hierarchical and temporal model of trait, role investment, and behavior relations in a sample of university students. Using two waves of assessment over 12 months, prospective path models showed that, controlling for Time 1 standing on trait self-control and typical weekly alcohol consumption, higher Time 1 subjective college student role investment predicted higher trait self-control scores, as well as lower typical weekly alcohol consumption and past week alcohol consumption. In addition, controlling for Time 1 typical weekly alcohol consumption and Time 1 past week alcohol consumption, the path models showed higher Time 1 trait self-control predicted lower typical weekly alcohol consumption and past week alcohol consumption 12 months later. Moreover, consistent with current thinking about the onset of alcohol consumption in early and middle adolescence as a general indicator of developmental risk (e.g., Brown et al., 2008), age of first drink was not only associated with greater alcohol consumption, but significantly less trait self-control as well.

The results showed the relative importance of subjective college student role investment compared to subjective family role and subjective friend role investment. In the context of trait self-control and alcohol consumption, subjective investment in family and friends played little to no role. This speaks to the primacy of being an invested college student compared to being an invested family member and/or friend. While subjective family or friend investment may be important to other traits and behaviors (e.g., agreeableness and empathic behaviors), these domains do not seem to be central to the expression of co-varying features of constraint/disinhibition. This is consistent with many college students’ experiences of moving and living away from their families of origin, where the immediacy of role investment may be diminished. It also might be the case that parental monitoring prior to college may be more influential on subsequent patterns of constraint/disinhibition (e.g., Pettit et al., 2001), rather than investment in one’s family per se.

While the paths for subjective college student role investment appear to be sensible and consistent with the social investment hypothesis, its measurement was constrained to a single three-item scale. It is possible these paths might be moderated by specific role-related experiences, such as being accepted into an honors program or college, being placed on academic probation, or belonging to a study group, that could result in a suppression or amplification of various path effects. Similarly, while the path for trait self-control to alcohol consumption was consistent with past research and the social investment hypothesis, it only represents a part of the profile of personality traits associated with psychological maturity. Whether such a model could be extended to traits related to emotional stability and agreeableness remains an open question.

As a whole, the findings provide a short-term view of the patterns of relations among inter-related components of constraint/disinhibition during a dynamic period in late adolescence and young adulthood. Over the relatively short time span of 12 months, meaningful prospective predictions were found, even for the highly consistent measure of trait self-control. Also noteworthy was the absence of trait-investment, behavior-investment, and behavior-trait pathways. In a way, the absence of these pathways lends credence to the neo-socioanalytic arrangement of the constructs; the intermediate construct of role investment showing relations to more general (i.e., trait self-control) and more specific (i.e., alcohol consumption) constructs. Only trait self-control showed cross-time relations to the measures of alcohol consumption (i.e., trait-behavior pathway). Ultimately, longitudinal mediation analyses will be needed to further elucidate how the various levels of the hierarchy influence one another over time.

Previous theoretical and empirical work has implicated normative role participation as a key feature in the development of psychological maturity (Lüdtke et al., 2011; Roberts & Caspi, 2003). However, this account is somewhat limited in that it does not capture individual differences in the level of involvement within a nominal role. The present account moves a step beyond categorical role participation to show how investigating individual differences in role investment – where role participation remains constant – can help illuminate the processes by which social identity and related behaviors develop over time. The results provide support for the social investment hypothesis by showing how greater subjective involvement and an increased sense of immersion in the college student role predict greater subsequent trait self-control and less alcohol consumption.

Highlights.

Greater initial student role investment predicted greater subsequent self-control

Greater initial student role investment predicted lower subsequent drinking

Greater initial trait self-control predicted lower subsequent drinking

Results show developmental importance of within-role individual differences

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant K99/R00 AA017877 to T. Bogg, with additional support from National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant R01 AA13650 to P.R. Finn. The authors thank Tiffany Barrios, Amy Chandler, Kaitlin King, and Joshua Paul for their assistance with the data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

As a further check on the possible altering effect of excluding participants with missing data at Time 2, we examined whether incorporating Time 1 data from these participants resulted in changes in the tested model. Using full information maximum likelihood (FIML) in a model that included the missing Time 2 participants’ data produced nearly identical estimates to those reported in the text and in Figure 1 (the only difference being a newly significant (p < .05) path from Time 1 MPQ control to Time 2 subjective college student role investment).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer LO, Hesselbrock VM. EEG, autonomic and subjective correlates of the risk for alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;54:577–589. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1993.54.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T. Conscientiousness, the transtheoretical model of change, and exercise: A neo-socioanalytic integration of trait and social-cognitive frameworks in the prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality. 2008;76:775–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00504.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T. Investigating drinking via the social investment hypothesis: Committed relationship status moderates the association between educational investment and excessive alcohol consumption among college students. Personality and Individual Differences. 2011;50:1104–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2011.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T, Finn PR. A self-regulatory model of behavioral disinhibition in late adolescence. Integrating personality traits, externalizing psychopathology, and cognitive capacity. Journal of Personality. 2010;78:441–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00622.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T, Roberts BW. Conscientiousness and health-related behaviors: A meta-analysis of the leading behavioral contributors to mortality. Psychological Bulletin. 2004;130:887–919. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogg T, Voss MW, Wood D, Roberts BW. A hierarchical investigation of personality and behavior: Examining neo-socioanalytic models of health-related outcomes. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:183–207. [Google Scholar]

- Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, Schulenberg J, et al. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Supp 4):S290–S310. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2243D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Bucholz K, Cadoret R, Cloninger CR, Dinwiddie S, Hesselbrock V, Nurnberger J, Reich T, Schmit I, Schuckit M. A new semi-structured psychiatric interview for use in genetic linkage studies: A report of the reliability of the SSAGA. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1994;55:149–158. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1994.55.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Kenny DA. A primer on regression artifacts. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. Impulse and constraint: Perspectives from personality psychology, convergence with theory in other areas, and potential for integration. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2005;9:312–333. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0904_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Temperament: A new paradigm for trait psychology. In: Pervin L, John O, editors. Handbook of personality: Theory and research. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 399–423. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Conger RD, Burzette RG. Personality development from late adolescence to young adulthood: Differential stability, normative maturity, and evidence for the maturity-stability hypothesis. Journal of Personality. 2007;75:237–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn PR, Mazas C, Justus A, Steinmetz JE. Early-onset alcoholism with conduct disorder: Go/No-Go learning deficits, working memory capacity, and personality. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26:186–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampson SE. Personality processes: Mechanisms by which personality traits “get outside the skin”. Annual Review of Psychology. 2012;63:315–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helson R, Kwan VSY, John OP, Jones C. The growing evidence for personality change in adulthood: Findings from research with personality inventories. Journal of Research in Personality. 2002;36:287–306. [Google Scholar]

- Helson R, Mitchell V, Moane G. Personality and patterns of adherence and nonadherence to the social clock. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1984;46:1079–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality, morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998 to 2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Cross-lagged panel correlation: A test for spuriousness. Psychological Bulletin. 1975;82:887–902. [Google Scholar]

- Levy B, Earleywine M. Reinforcement expectancies for studying predict drinking problems among college students: Approaching drinking from an expectancies choice perspective. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:551–559. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00250-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littlefield AK, Sher KJ, Wood PK. Is “maturing out” of problematic alcohol involvement related to personality change? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:360–374. doi: 10.1037/a0015125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodi-Smith J. University of Illinois: Urbana-Champaign; 2007. Examining the social investment hypothesis: The relationship of social role investment and personality trait development in adulthood. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, [Google Scholar]

- Misra S, Ghosh R, Kanungo RN. Measurement of family involvement: A cross-national study of managers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1990;21:232–248. [Google Scholar]

- Lüdtke O, Roberts BW, Trautwein U, Nagy G. A random walk down university avenue: Life paths, life events, and personality trait change at the transition to university life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101:620–637. doi: 10.1037/a0023743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neugarten BL, Moore JW, Lowe JC. Age norms, age constraints, and adult socialization. American Journal of Sociology. 1965;70:710–717. doi: 10.1086/223965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Laird RD, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Criss MM. Antecedents and behavior-problem outcomes of parental monitoring and psychological control in early adolescence. Child Development. 2001;72:583–598. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A. The cumulative continuity model of personality development: Striking a balance between continuity and change in personality traits across the life course. In: Staudinger RM, Lindenberger U, editors. Understanding human development: Lifespan psychology in exchange with other disciplines. Dordrecht, NL: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2003. pp. 183–214. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132:1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Wood D. Personality development in the context of the neo-socioanalytic model of personality. In: Mroczek DK, Little TD, editors. Handbook of personality development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2006. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Wood D, Caspi A. The development of personality traits in adulthood. In: John OP, Robins RW, Pervin LA, editors. Handbook of personality psychology: Theory and research. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 375–398. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Wood D, Smith JL. Evaluating five factor theory and social investment perspectives on personality trait development. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:166–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK. Becoming who we are: Temperament and personality in development. New York: Guilford; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A. Brief manual of the multidimensional personality questionnaire. University of Minnesota; 1982. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Vaidya JG, Gray EK, Haig JR, Mroczek DK, Watson D. Differential stability and individual growth trajectories of Big Five and affective traits during young adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2008;76:267–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]