Phage lytic enzymes have potential as new inroads toward novel antibiotics. Until now this approach has only been promising for Gram-positive bacteria because in Gram-negatives the target of lytic action is protected by an outer envelope. Information gleaned from the structural studies of two plague proteins—pesticin and FyuA—allowed us to engineer a “hybrid” protein to address this problem. This hybrid consisted of T4 phage lysozyme linked to a FyuA targeting domain and was capable of killing Gram-negative cells. This work therefore presents a proof of principle that phage lytic enzymes can be engineered to cross the outer envelope. Furthermore, hybrid engineering handed us a tool for the mechanistic investigation of TonB mediated membrane transport. This commentary describes our recent efforts to test the efficacy of the hybrid in a mouse infection model and the directions this work might take in the future.

In an age of rising antibiotic resistance humanity desperately needs to investigate new paths to antimicrobial chemotherapy. There are now several reports that show that lytic enzymes isolated from phages may work well as therapeutic agents against diseases caused by Gram-positive bacteria (Fischetti, Trends Microbiol 2005). Yet there is a problem in applying the same strategy to Gram-negative pathogens. The target of the toxic action of the lytic enzymes is a structural layer known as peptidoglycan which in Gram-positive bacteria is exposed but in Gram-negative organisms is sequestered beneath a protective outer membrane where the lytic enzyme cannot reach it.

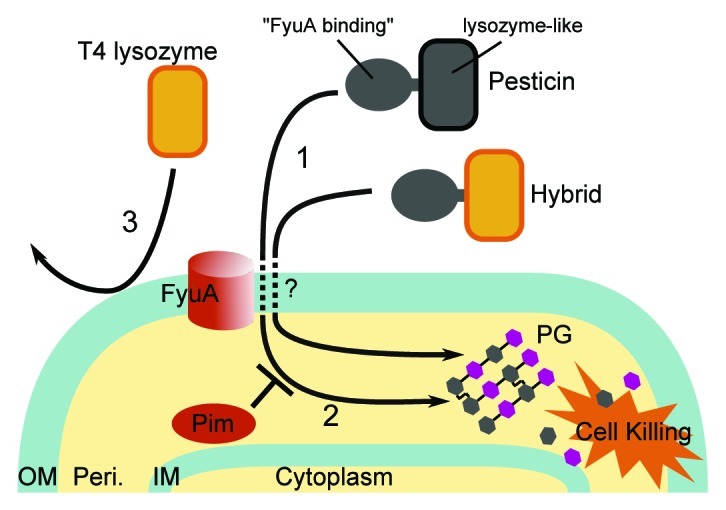

Unexpectedly we found a way of addressing this problem by using X-ray crystallography to study a system of two interacting proteins from the plague bacterium (Lukacik et al., Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012). One of these proteins was a bacterial toxin called pesticin, whose toxic efficacy depends on the presence of a second protein FyuA in the outer membrane (Fig. 1). The crystal structures revealed FyuA to be a classical outer membrane TonB-dependent iron transporter consisting of a β barrel whose pore was blocked by a plug domain (Noinaj et al., Annu Rev Microbiol 2010). Pesticin on the other hand was comprised of two distinct domains and we noticed that the structure of the C-terminal domain resembled the well-studied lysozyme from T4 phage. Guided by the structure we switched the pesticin lysozyme-like domain for T4 lysozyme to construct a “hybrid” protein. The hybrid protein now consisted of a lytic domain linked to an N-terminal pesticin domain that we determined to be responsible for FyuA binding. The addition of this hybrid to the archetypal Gram-negative organism—E. coli (modified to express fyuA in the outer membrane)—resulted in direct killing without the need for physical disruption of the outer membrane using chelators, pressure, temperature changes or eukaryotic antimicrobial peptides. Like with pesticin this killing was fyuA-dependent. Overall this experiment provides a proof of principle that phage lytic enzymes such as T4 lysozyme can be engineered to target Gram-negative bacteria.

Figure 1. Mode of action of pesticin and an engineered hybrid protein: (1) The Pesticin molecule consists of a N-terminal “FyuA binding” and a C-terminal lysozyme-like domain. After traversing the outer membrane pesticin degrades the peptidoglycan structural layer present in the periplasm resulting in cell killing. This translocation depends on an outer membrane protein and virulence factor—FyuA—but the mechanism by which this happens is not yet understood. (2) The lysozyme-like domain of pesticin was substituted for T4 lysozyme to create a hybrid protein. The translocation of a hybrid also results in killing but unlike with pesticin this process is not inhibited by a periplasmic Pim protein. (3) Without additional means of disrupting the OM the externally added T4 lysozyme cannot effect killing. Abbreviations used in the figure: OM, outer membrane; Peri., periplasm; IM, inner membrane; PG, peptidoglycan.

It would be misleading to interpret this experiment as a simple replacement of a homologous domain. In fact the functional and structural differences between the two are large enough to broaden the native antimicrobial spectrum of pesticin to include other bacteria, namely ones that are normally immune to pesticin by virtue of a pesticin immunity protein—Pim. We have demonstrated this both in an E. coli model where the fyuA and pim genes were artificially expressed and in pathogenic Yersinia pestis strains.

The construction of the hybrid protein also provided us with a first tool to chip away at the long elusive mechanism of TonB-mediated transport. An important finding from this study was that the presence of engineered disulfides (Matsumura and Matthews, Science 1989) within the T4 lysozyme domain of the hybrid that join residues far apart in the sequence did not completely eliminate the import. This finding was quite surprising since the FyuA barrel pore is too narrow to accommodate a fully folded lytic domain even if the pore-blocking plug domain is displaced. Within the field, toxin unfolding is generally accepted to be a pre-requisite of TonB facilitated import (Cascales et al., Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2007). We expect that this potentially controversial finding will raise a response in the literature and indeed Patzer et al. (J Biol Chem 2012) have recently shown that similar introduction of disulfide bonds has led to a complete loss of hybrid activity. The conflicting results could simply be due to differences in the constructs and experimental setup. For example we tested a hybrid mutant that contained two disulfide bonds while the closest match that Patzer et al. tested contained one of the equivalent disulfide bonds but lacked the other. There are other differences between our constructs such as the presence and position of the affinity tag, the junction between the N-terminal pesticin and T4 lysozyme domains and a point mutation in the T4 lysozyme domain. For the experimental setups, we performed our killing assay in broth and then plated the survivors for counting while Patzer et al. performed a plate assay and observed zones of lysis. If Patzer et al. are correct, the most plausible explanation is that a small population of our mutant hybrid was reduced and therefore still active. However we found no evidence of such a population either by Coomassie gel staining or by mass spectrometry.

It is important not to neglect FyuA in the discussion of this work. Presence of the fyuA gene is a reoccurring theme in the literature investigating heightened virulence of human and animal pathogenic E. coli strains. Recent reports also tell that fyuA appears to be associated with relapse and persistence of urinary tract infections (Ejrnaes et al., Virulence 2011) and multi drug resistance in animal and human infections (de Verdier et al., Acta Vet Scand 2012; Platell et al., Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012). Targeting fyuA for antimicrobial therapy now offers some very tantalizing prospects. Since bacteria producing FyuA are not part of a healthy bacterial flora we can in theory selectively kill only the virulent organisms and leave the rest unharmed. The broad killing by commonly used antibiotics probably promotes the spread of resistance genes among the human microbiota. More than this, targeting FyuA now has the potential to eliminate the infections that are most persistent and difficult to treat, such as ones caused by drug resistant strains. When considering limitations, it is clear that this approach will not be applicable to all Gram-negative pathogens since not all express FyuA. This is not a great concern because the power of this approach is its selectivity rather than indiscriminate killing. However a possible problem is loss of FyuA due to selective pressure. This may be especially pertinent since Gram-negative pathogens possess a number of alternative iron acquisition mechanisms of which FyuA is only one. On the other hand, FyuA is required for virulence in the early stages of bubonic plague so loss of this iron transporter would result in decreased infectivity/toxicity of the strain.

An obvious and challenging future path of investigation would be to demonstrate that the antimicrobial approach presented by the hybrid protein has medical relevance by first showing that it is effective in a mouse infection model. We have already attempted to carry out initial animal studies where mice were infected intranasally with 1000 cfu Y. pestis C092. Following infection, high concentrations of the hybrid were administered also intranasally. A number of hybrid instillation intervals were tested in order to identify an optimum protocol—co-infusion, a single dose after 1.5 h or two doses after 2 and 24 h. Since no such optima were identified these experiments were grouped into a single hybrid treated cohort and the survival results are presented in Table 1. Because the sample sizes were small, the Fisher Exact test was used to compare the two groups. The p value is 0.13, above the cut-off of 0.05, so the difference in the survival rates is not statistically significant. Table 1 shows the exact 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the two percentages. These CI overlap, which is consistent with the p value. Nevertheless our data hint that increasing the number of animals in this experiment might have given a small but significant difference in favor of a protective effect conferred by the hybrid. It is difficult to speculate on the reasons for this low efficacy. Perhaps the TonB-dependent transport of a large hybrid molecule is very slow compared with the speed of bacterial adhesion and subsequent infection. Additionally, in carrying out these experiments we were faced with a number of severe technical challenges in particular with the production of large amounts of hybrid protein and intranasal administration of large hybrid protein droplets which were concentrated to their protein solubility limit. Maybe these experiments could be revisited once the bactericidal activity of the hybrid toxin has been improved as is suggested in the original manuscript.

Table 1. Survival of mice following infection with Y. pestis C092.

| N mice | Survivors | % Surv | Exact 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

28 |

14 |

50.0% |

31–69% |

| Hybrid treated | 37 | 26 | 70.3% | 53–84% |

Instead of improving hybrid activity one might take a different approach altogether. A different toxic domain unrelated to T4 lysozyme could be attached while retaining the FyuA targeting capacity of the N-terminal pesticin domain. Only further research will tell which of these approaches, if any, will be successful in the future. In the meantime the pressing urgency for antibiotic discovery remains.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. S.K.B. and B.J.H. acknowledge support from a trans-NIH Biodefense grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. We thank Elizabeth Wright (NIDDK) for statistical analysis of the data.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/virulence/article/22683