Abstract

The mechanisms controlling vascular development, both normal and pathological, are not yet fully understood. Many diseases, including cancer and diabetic retinopathy, involve abnormal blood vessel formation. Therefore, increasing knowledge of these mechanisms may help develop novel therapeutic targets. The identification of novel proteins or cells involved in this process would be particularly useful. The retina is an ideal model for studying vascular development because it is easy to access, particularly in rodents where this process occurs post-natally. Recent studies have suggested potential roles for laminin chains in vascular development of the retina. This review will provide an overview of these studies, demonstrating the importance of further research into the involvement of laminins in retinal blood vessel formation.

Keywords: laminin, retina, blood vessels, angiogenesis, astrocytes, development

Many blinding retinal diseases, including diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity, involve the development of abnormal vasculature. This pathological angiogenesis is believed to occur via the same actors as normal retinal vessel development. Therefore, elucidating the mechanisms regulating normal vascular development will also aid in understanding these pathological conditions. Furthermore, knowledge obtained from studying the retina can be transferred to angiogenesis in general, including that related to tumor formation. The retina is an easily accessible, non-invasive model in which to study vascular development. This is particularly true in rodents in which retinal vessels develop post-natally.

As recently reviewed by Simon-Assmann and colleagues, several lines of evidence suggest that laminins are important in vascular development.1 The current review will focus on the potential role laminins play in vascular development of the mouse retina. Laminins are heterotrimeric glycoproteins and there are currently 16 known laminin isoforms,2 each containing an alpha (α), beta (β) and gamma (γ) chain. A number of laminin chains are expressed in the basement membrane of the retinal vessels and in the retinal basement membranes where they could influence vascular development.

Retinal Structure

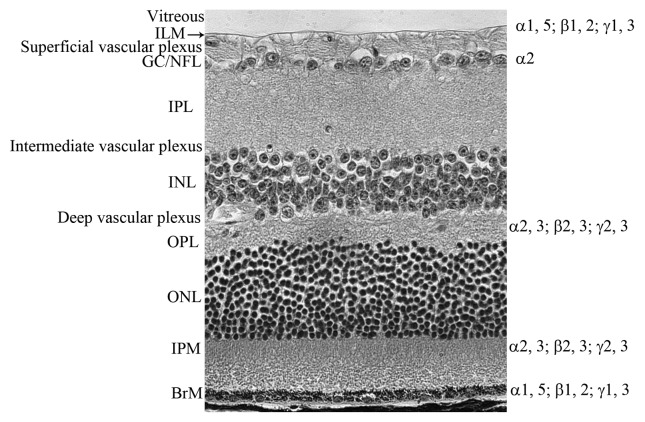

The retina is the nervous tissue that lines the inner surface of the eye and is separated from the lens by a gel-like substance known as the vitreous. Two basement membranes create borders for the retina. The inner limiting membrane (ILM) separates the retina from the vitreous while Bruch’s membrane separates it from the choroid. The adult retina contains three layers of neurons. From the vitreous, these are: the ganglion cell layer, the inner nuclear layer (INL, containing the bipolar, horizontal and amacrine cells) and the outer nuclear layer (ONL, containing the photoreceptors). These retinal neuronal layers are separated by synaptic layers known as the inner and outer plexiform layers (IPL and OPL respectively). Müller cells, the primary glial cell of the retina, have their nuclei in the INL and extend primary processes throughout the entire retina, coming in close contact with most other cells, including endothelial cells. These glial cells assume many homeostatic roles in the retina. Ganglion cell axons extend across the retinal surface in bundles and exit to the brain via the optic nerve. The ganglion cell/nerve fiber layer also contains the other glial cell of the retina, astrocytes, that surround retinal vessels to form the blood retinal barrier. The structure of the retina is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The definition of retinal layers. An adult retinal section stained with hematoxylin and eosin demonstrating the layers of the retina. From the vitreous, labeled on the left side, these are: ILM, inner limiting membrane; GC/NFL, ganglion cell/nerve fiber layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; ONL, outer nuclear layer; IPM, interphotoreceptor matrix; BrM Bruch’s membrane (BrM). The laminin chains are shown on the right side where they are expressed in the retina.

Retinal Blood Vessel Development

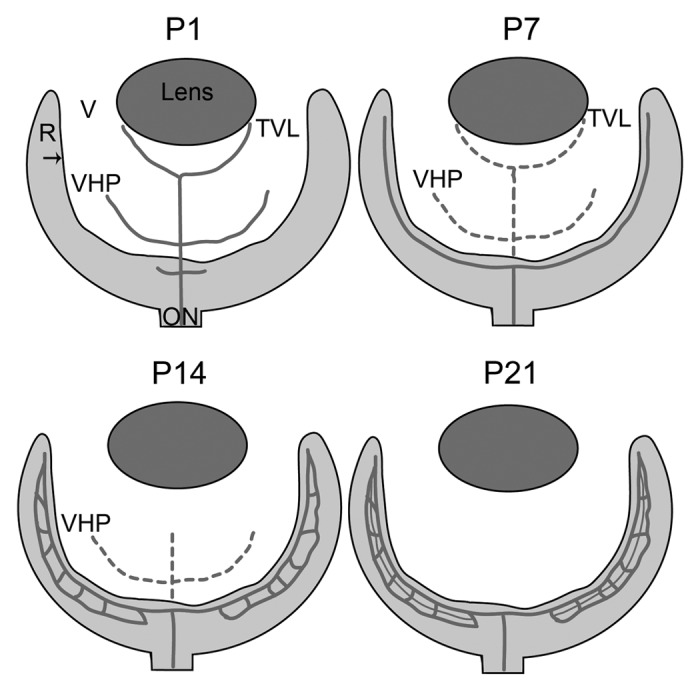

The mouse retina is nourished by three layers of retinal vessels: the superficial, intermediate and deep layers, as well as the choroidal vessels, which feed the photoreceptors. As the steps involved in retinal vascular development have been reviewed,3,4 they will not be discussed extensively here. Briefly, retinal vessels develop post-natally in rodents and in mid-gestation in humans. Prior to the development of the retinal vasculature, the retina is nourished by embryonic vessels known as hyaloid vessels, residing in the vitreous. This hyaloid vasculature is composed of the tunica vasculosa lentis (TVL) and the vasa hyloidea proprea (VHP). The TVL nourishes the lens while the retina is supported by the VHP. As the retinal vessels develop, the hyaloid vessels regress to create a transparent vitreous. This regression is normally complete by post-natal day (P) 21 in the mouse5 and by birth in humans. While the mechanisms behind hyaloid regression are not fully understood, this is believed to involve macrophage-induced apoptosis.6 Hyaloid and retinal vessels share a common artery supply which emerges through the optic nerve head. Therefore, it has been suggested that reduced blood flow in the hyaloid vessels is partially responsible for the regression of the VHP.5,7 For a more thorough review of hyaloid regression, the reader is directed to the recent review by Ito and Yoshioka.5

Mature retinal vessels in the mouse form via angiogenesis, or the budding of vessels from pre-existing vessels.4,8,9 The superficial, or primary, retinal vasculature, which lies in the ganglion cell layer, develops during the first week. The vessels in this plexus have a spoke-like pattern, resembling spokes on a wheel. Between P7 and 10, these superficial retinal vessels dive into the retina to form two additional layers of vessels. The deep vascular plexus, in the OPL, is complete by P14 while the intermediate plexus forms by P21 in the IPL8 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. A schematic of retinal vascular development in the normal mouse. Depicted are the key stages in normal vascular development in the mouse. Solid lines indicate blood vessels while broken lines indicate vessels that are regressing. At P1, the hyaloid vasculature in the vitreous (V; white area) consists of the vasa hyloidea proprea (VHP) and the tunica vasculosa lentis (TVL) and the retinal vessels have begun forming. By P7, the superficial vascular plexus in the retina (R) is complete and the TVL and VHP have begun to regress. At P14, the deep retinal plexus is formed and the TVL has regressed. The intermediate plexus forms and the hyaloid vessels completely regressed by P21. The arrow indicates the ILM.

While the mechanisms controlling vascular development in general are beginning to be understood,10,11 this process in the retina is not yet fully elucidated. Retinal vessels in the mouse are preceded by an astrocyte template, which is thought to provide guidance.8,9 Astrocytes enter the retina from the optic disc beginning around embryonic day 15 with vessels beginning to form around P1.8 Different factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and R-cadherin, from astrocytes are believed to provide cues which guide retinal vessel formation.8 Increased neuronal metabolism is hypothesized to increase astrocyte production of VEGF.12 The ablation of VEGF in astrocytes, however, does not prevent vessel formation,13 suggesting that other cell types and proteins are also involved in this process. The location of Müller cell endfeet at the ILM makes these cells excellent candidates for guiding vascular development. Indeed, these glial cells are assumed to stimulate the diving of retinal vessels to the outer retina by producing VEGF.12 Therefore, it seems probable that they could guide the superficial plexus formation as well.

The potential involvement of cells other than astrocytes in retinal vessel formation is supported by the fact that retinal vessels form ahead of the astrocyte template in dogs14 and man.15 In addition, these vessels form via vasculogenesis from precursor cells, known as angioblasts.14,16,17 This process is completed in humans at birth but occurs post-natally in the dog. These developing vessels are followed closely by astrocytes migrating from the optic nerve.15 As in the mouse, astrocytes ensheath developing vessels, helping to form the blood retinal barrier. Deeper in the retina, Müller cells are part of the blood retinal barrier.

The Expression of Laminin Chains in the Retina

Laminins are found in the two retinal basement membranes, the ILM and Bruch’s membrane as well as the interphotoreceptor matrix (IPM) and OPL.18 The expression of laminin chains within the retina is summarized in Table 1 and Figure 1. The developmental expression of laminin has been examined in mouse and chick eyes.19 In the mouse, the α2 chain is detected as early as embryonic day (E) 13.5 (the earliest time point reported) in the optic nerve, chiasm, retina and hyaloid vessels. By early post-natal development, laminin α2 is also found in the ganglion cells and nerve fiber layer, consistent with a role for this chain in guidance of retinal ganglion cells.19 A later study investigated the expression of individual laminin chains in the fetal human retina.20 The ILM contains laminins α1, α5, β1, β2 and γ1 from 9 to 20 weeks gestation (WG).20 Bruch’s membrane contains all of these chains plus α3 and α4. Interestingly, α1 expression in Bruch’s membrane decreases with age and is not detected at 20WG while α4 expression increases with age.20

Table1. Laminin chain distribution during retinal development.

| Laminin chain | Retinal expression | Ages detected | Biological function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| α1 |

ILM |

9 WG-adult (Hn), |

Binds ILM to receptors on Müller cells. Defects disrupt retinal vascular development |

18 and 20 |

| BrM |

9 WG-adult, decreases with age in fetal ages |

|||

| |

|

(Hn) |

|

|

| α2 |

BMs surrounding ON, retina and OC |

E13.5 (Ms) |

Provides guidance for developing ganglion cells. |

19 |

| ON, OC, GC, NFL, BV |

Birth- adulthood |

|||

| α3 |

BrM |

9–20 WG (Hn) |

Retinal synapse formation. |

18 and 20 |

| IPM and OPL |

Adult (Hn, rat) |

|||

| α4 |

ILM, BrM |

9–20 WG, increases with age (Hn) |

Formation of BrM |

20 |

| IPM, OPL, Müller cells |

Adult (Hn, rat) |

Retinal synapse formation |

18 |

|

| BV (tip cells) |

Adult (Hn, rat), birth-P5 (Ms) |

Regulates vascular branching by activating Delta-like4/Notch1 pathway |

22 |

|

| α5 |

ILM, BrM |

9 WG-adult (Hn) Adult (rat) |

Formation of ILM and BrM |

18 and 20 |

| BV (endothelial cells), astrocytes |

birth-P5 (Ms) |

|

22 |

|

| β1 |

ILM, BrM |

9 WG-adult (Hn) |

Formation of ILM and BrM |

18 and 20 |

| β2 |

ILM, BrM |

9 WG-adult (Hn) |

Formation of ILM and BrM |

18 and 20 |

| IPM and OPL |

Adult (Hn, rat) |

Retinal synapse formation |

18 |

|

| β3 |

IPM and OPL |

Adult (Hn, rat) |

Retinal synapse formation |

18 |

| γ1 |

ILM, BrM |

9 WG-adult (Hn) |

Formation of ILM and BrM, BV wall |

18 and 20 |

| γ2 |

IPM and OPL |

Adult (Hn, rat) |

Retinal synapse formation |

18 |

| γ3 | IPM and OPL |

Adult (Hn, rat) |

Retinal synapse formation |

18 |

| BV, BrM, ILM, amacrine cells | Birth-adult (Ms) | Development of microvasculature | 21 |

Shown is a summary of the laminin chains found in the retina as has been reported in the mouse, rat and human. Abbreviations used: BM, basement membrane; BrM, Bruch’s membrane; BV, blood vessels; E, embryonic day; GC, ganglion cells; Hn, Human; ILM, inner limiting membrane; IPM, interphotoreceptor matrix; Ms, Mouse; NFL, nerve fiber layer; ON, optic nerve; OC, optic chiasm; OPL, outer plexiform layer; WG, weeks gestation.

The expression of laminin chains within the retina has also been examined in adult human and rat retinas.18 The ILM and Bruch’s membrane both contain laminins α1, α5, β1, β2 and γ1 while the α3, α4, β2, β3, γ2 and γ3 chains are found in the IPM and OPL.18 The components in the photoreceptor matrix and plexiform layers may be important for retinal synapse formation.18 Laminin α4 is also found in Müller cells as well as, along with the α2 and α5 chains, the retinal vasculature.18

More recently, the expression of laminin chains associated with retinal vessels has been investigated. One study looked at laminin γ3 in the mouse retina.21 This chain is most prominent in Bruch’s membrane and vascular basement membranes but also detected in the ILM and a subpopulation of amacrine cells. From the development of retinal vessels into adulthood, laminin γ3 is closely associated with the microvasculature of retinal vessels.21 Another recent study looked at the expression of laminins α4 and 5 within the developing mouse retinal vasculature.22 Laminin α4 mRNA is most highly expressed in the tip cells at the edge of the developing vasculature while that of laminin α5 is primarily in the vascular plexus.22 The laminin α4 protein, however, appears to be less restricted as it is detected in the endothelial cells of retinal vessels but not in the tip cell filopodia. Laminin α5 protein is found in both endothelial cells and retinal astrocytes.

Formation of the ILM

Of the basement membranes, the ILM is particularly pertinent to the current review as it lies just above the superficial retinal vascular plexus. The development of the ILM appears to be unique in that the cells binding it do not produce its components. Rather, it has been hypothesized that these proteins are produced by the lens and ciliary body and released into the vitreous, where they are stored until the ILM forms.23-27 While this is an unusual basement membrane formation, it is well supported by the mRNA expression patterns for the ILM proteins and receptors.

It has been demonstrated in the chick that laminin-111 and other ILM components, including collagens IV and XVIII, nidogen and perlecan are produced by the lens, ciliary body and epithelia surrounding the optic disc rather than within the retina.23,26,27 In the mouse eye, the only ILM component shown to be produced within the retina is laminin β1.28 The other proteins in this structure are synthesized in the lens and ciliary body.28,29 Similarly, the human retina does not contain mRNA for laminins α1, α2, β1 and γ118 or collagen IV.25 Adult human Müller cells, however, contain laminin β230 and γ3 mRNA.18 During embryonic development, as the eye and ILM are increasing in size, the vitreous of both humans and chicks contains large amounts of all ILM components but these levels decrease rapidly and are barely detected in the adult vitreous.26,27

When the ILM is disrupted in the chick retina via collagenase, intravitreal injections of laminin-111, but not other ILM components, initiate the reconstitution of this structure.24 Furthermore, this reconstitution can be blocked by an antibody against laminin-111. Together, these data have led to the speculation that laminin-111 is the key molecule to start the formation of the ILM by binding to receptors on Müller cells.24 A similar feature has been described for the formation of the Reichert basement membrane, which is not formed after the deletion of LM-11131,32 or laminin receptors, such α dystroglycan.33 This hypothesis is supported by the fact that laminin α1, the α chain of laminin-111, holds the binding sites which anchor the ILM to receptors, such as integrins and dystroglycan,34,35 which are found on Müller cells.36-39 Other ILM components within the vitreous are believed to then bind to this stabilized laminin-111.25,26 Together, these data suggest that laminin α1 is crucial for forming and maintaining the integrity of the ILM.

Lessons from Laminin Mutant Models

Laminin α1

The potential importance of Lama1, the gene coding for the laminin α1 chain found in only two laminin isoforms, in vascular development within the eye was first suggested by studies in zebrafish.40 Twenty-four hours after fertilization, endothelial cells of the hyaloid vessels in Lama1 mutant zebrafish larvae lack capillaries. In addition, blood flow is reduced compared with controls and the mutants die as larvae, making it impossible to assess the long-term phenotype. Similarly, the deletion of Lama1 in mice causes embryonic lethality due to the failure to form Reichert’s membrane, which allows maternal blood to enter the yolk sac.31,41 Two mouse models with mutations in Lama1 were recently identified that survive into adulthood and experience severe retinal defects.42,43 One mutant, known as Lama1nmf223, bears a recessive mutation in the LN domain of Lama1.42 The other mutant, Lama1Δ/Δ, was generated using a floxed allele for Lama131 crossed with Sox2-Cre mice, which eliminates expression in the embryo while allowing the formation of Reichert’s basement membrane.42

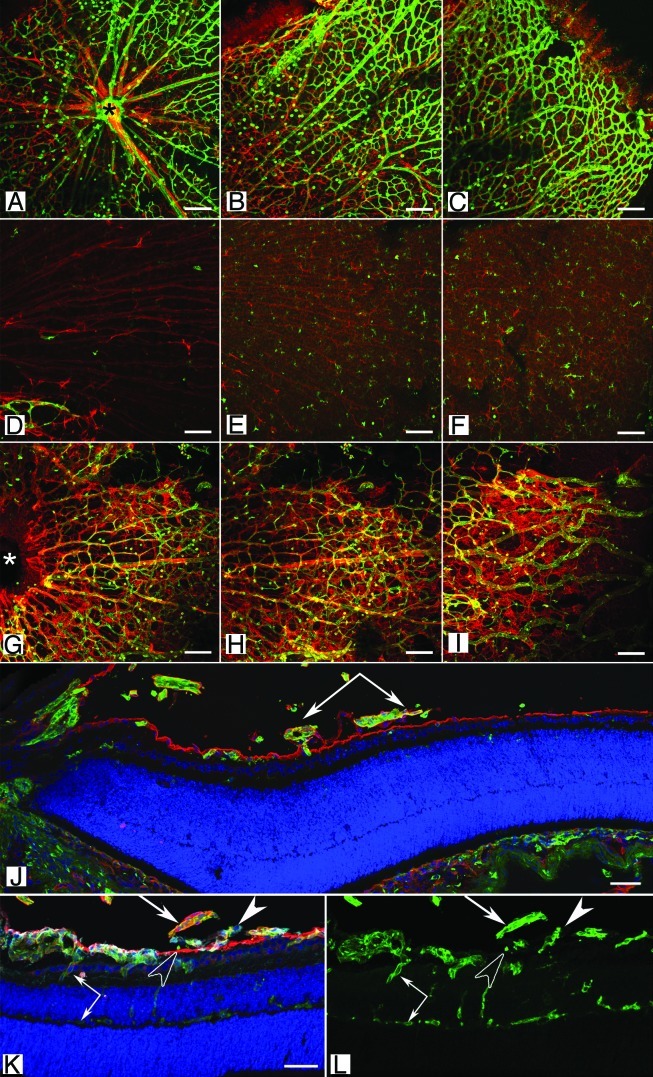

Lama1Δ/Δ mice experience cerebellum defects resulting in abnormal neuronal migration and cell proliferation causing motor problems.44,45 In addition, the development of the retinal vasculature is disrupted.42,43 Interestingly, despite the differences in molecular origin and effects on laminin α1 expression, the two Lama1 mutants have similar retinal phenotypes. Retinal vessels emerge at P0 in the Lama1 mutants, as they do in the control mouse, as an apron of retinal vessels surrounding the optic nerve head. Therefore, the Lama1 mutations do not affect the differentiation or initial migration of endothelial cells. By P3, however, Lama1 mutant retinal vessels have traversed the ILM, along with astrocytes, into the vitreous. Once in the vitreous, these vessels are indistinguishable from the hyaloid vessels and extend across the vitreal surface of the ILM but no superficial vascular plexus forms in the retina (Fig. 3). Astrocytes wrap around these vessels, creating a dense vitreal membrane (Fig. 3D–I). The vitreal vessels dive into the outer retina between P7 and P10 to form the deep and, later, intermediate retinal vascular plexi (Fig. 3K and L). Thus, despite lacking a superficial vasculature within the retina, the intermediate and deep vascular plexi form at the correct ages in the Lama1 mutants.

Figure 3 (See opposite page). Retinal vascular defects in the Lama1 mutant mice. (A–I) Retinal flatmounts from P7 mice were stained with GFAP (red; astrocytes) and GS isolectin (green; blood vessels). In the wild type retina (A–C), vessels and astrocytes spread across the entire retina. Hyaloid vessels (arrows) have begun regressing. By contrast, the retina of Lama1nmf223 mice (D–F) has a vastly reduced number of astrocytes with vessels only in the peripapillary region (D). (A, D, G = peripapillary region; B, E, H = midperiphery; C, F, I = far periphery). When the Lama1 mutants retinas are stained with the hyaloid vessels intact (G–I), astrocytes ensheath these vessels and form a membrane in the vitreous. A cross section from a P7 Lama1 mutant stained with GS isolectin (green) and laminin (red) demonstrates the exit of retinal vessels into the vitreous. Cross sections from P10 Lama1nmf223 eyes labeled with PDGFRα (light blue; astrocytes), GS isolectin (green), anti-pan laminin (red; ILM) and DAPI (blue) show vessels from the vitreous branching into the retina. The inner retinal vessels are forming from these diving vessels (paired arrows). Astrocytes expressing laminin (solid arrowhead) on the vitreal side of the ILM (open arrowhead) near the VHP (arrows). Scale bars indicate (A–I), 100 µm; (J–L), 50 µm. Images in this figure were originally published in BMC Developmental Biology.43

These data suggest that a fully functional laminin α1 is necessary for the migration of retinal astrocytes and, subsequently, endothelial cells in the mouse retina. Laminin α1 could guide astrocyte and endothelial cell migration through direct interactions or indirectly through its binding partners. The localization of this protein above the nerve fiber layer and its early expression during development would be ideal for a protein guiding astrocytes across the retinal surface.

Yet another possibility is that laminin α1, as an adhesion molecule, guides Müller cell processes and their endfeet to their position at the ILM during development. Indeed, in vitro, laminin-111 stimulates Müller cell migration and guides process formation.46 In both Lama1 mutants, many Müller cells extend endfeet beyond the ILM into the vitreous as early as P0.5.42,43 This extension into the vitreous could be driven by the laminin on the basement membrane of hyaloid vessels. Since Müller cells produce VEGF,12 which can stimulate astrocyte proliferation and migration,47 this could explain the abnormal migration of astrocytes into the vitreous. Further work is warranted to better understand the influence of Müller cells in guiding retinal astrocyte and blood vessel development in the retina.

The retinal phenotype observed in Lama1 mutants has some features found in two different human syndromes, persistent fetal vasculature (PFV)48,49 and Knobloch syndrome.49 The glial membrane formed in Lama1 mutants is similar to that associated with proliferative vitreoretinopathy, a complication occurring after retinal surgery or in diabetes.50-53 In both PFV and Knobloch syndrome, the hyaloid vasculature fails to regress as they normally do once retinal vessels have formed.48,49 Müller cells and astrocytes also enter the vitreous, ensheathing hyaloid vessels and creating a glial membrane.54-56 Together, these abnormalities cause traction on the retina, leading to retinal detachment and blindness at a young age. Therefore, the two Lama1 mutants could be valuable in identifying treatments for such retinal diseases. In addition, this suggests that mutations in LAMA1 could lead to retinal disease in humans and should be added to screenings, particularly in the cases of PFV and Knobloch syndrome.

Laminin α4

Lama4 encodes the laminin α4 chain, which is found in four laminin isoforms. This chain is expressed by blood vessel cells and participates in the formation of blood vessel basement membranes.57 Its invalidation in mice leads to hemorrhages during development and at birth, due to an endothelial basement membrane defect. This defect is compensated at 3 weeks of age as blood vessels are stabilized by the accumulation of laminin α5.58 The retinal vascular development in Lama4−/− mice was recently investigated.22 At P5, when the primary retinal vasculature is approximately 70% complete, the vascular density is significantly higher in the Lama4−/− mice compared with controls. This is accompanied by an increase in branching and tip cell formation as well as reduced vascular maturation and lumen size. Endothelial cell proliferation is also significantly elevated in the Lama4−/− mice. It was further demonstrated that several Notch1 actors, including Hey1, Hey2, Nrarp and Dll4, are reduced in the Lama4−/− mice. These data indicate that laminin α4 may initiate Dll4/Notch interactions and this role was confirmed using notch inhibitors. Hypersprouting of retinal vessels and reduced Dll4 expression in tip cells is also observed by endothelial cell-specific deletion of integrin β1 during early post-natal retinal development. These results led the authors to conclude that laminin α4, through adhesion to integrins, activates Dll4 and, thus, the Notch pathway.22 While this report eloquently described the role of laminin α4 in the initial stages of retinal vascular development, it did not go beyond P5. As the retinal vasculature is not fully developed until P21 in the mouse, it would be interesting to know how the intermediate and deep vascular plexi are affected by the loss of Lama4.

Laminin β2

Lamb2 encodes the laminin β2 chain that is found in the retinal basement membranes and plexiform layers.18 Mutations in LAMB2 have been shown to cause Pierson syndrome, a fatal congenital nephrotic condition that also causes ocular abnormalities.59,60 The ocular defects in Pierson syndrome vary among patients but include microcorcia, glaucoma, cataracts and retinal detachment as well as PFV.59 As mentioned above, PFV can in fact cause the other ocular anomalies observed in patients with Pierson syndrome. While the etiology of this condition is not understood, one could speculate that the ILM may be altered, as in Lama1 mutant mice, since laminin β2 is found in this basement membrane and together with laminin α1 in the 121 laminin isoform.18

The role of Lamb2 in the retina has also been investigated using Lamb2 null mice. The loss of laminin β2 disrupts dopaminergic neuron and rod photoreceptor synapses development, leading to abnormal electroretinograms.61,62 As suggested by Pierson syndrome, the ILM does not form properly in Lamb2−/− in mice.63,64 Consequently, Müller cell endfeet of Lamb2−/− mice associate with blood vessels and the polarity of these cells is abnormal. No retinal vascular defects have been reported in the Lamb2−/− mice.

Laminin γ3

The Lamc3 gene encodes the laminin γ3 chain, found in five laminin isoforms.2 Laminin γ3 is expressed in the microvasculature of the retina as well as the ILM and Bruch’s membrane.21 The potential role of this protein in retinal vascular development was recently investigated using a Lamc3 knockout mouse.21 Despite the widespread expression of this laminin chain within the retina, neither retinal lamination nor the development of individual retinal cells is altered by the deletion of Lamc3. The retinal vasculature, however, is altered in Lamc3 knockout mice. In contrast to the Lama1 mutants described above, the Lamc3 mice develop a normal primary and intermediate plexi with artery and vein development unaffected. The deep vascular plexi, at the layer of the OPL, however, has an increased number of capillaries resulting from increasing branching.21 Therefore, it appears that Lamc3 may be involved in regulating the migration of endothelial cells within the outer retina.

The retinal defects associated with the deletion of Lamb2 were worsened when Lamc3 was also deleted.61,64 Müller cell processes and ganglion cells were observed entering the vitreous.64 Lamb2 and Lamc3 double knockout mice also had a thickened Bruch’s membrane, hyperplastic retinal pigment epithelial cells, disorganized and shortened photoreceptor outer segments, retinal dysplasia and synaptic defects.64

Conclusions

The available data clearly demonstrate the importance of laminins in retinal vascular development. Further research is required to fully appreciate how laminins function in retinal vascular development and to look at the influence of other laminin chains. In addition, the influence of laminin receptors, such as integrins and dystroglycan, on retinal vascular development should also be investigated. The mouse models reviewed herein will help elucidate the regulation of vascular development.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Gerard Lutty for careful review of this manuscript and D. Scott McLeod for assistance with figure preparation and manuscript review. This work was supported by the Knight’s Templar Eye Foundation and the National Institute of Health [EY-09357 (G.L.)].

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/22480

References

- 1.Simon-Assmann P, Orend G, Mammadova-Bach E, Spenlé C, Lefebvre O. Role of laminins in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55:455–65. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.103223ps. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yurchenco PD. Basement membranes: cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saint-Geniez M, D’Amore PA. Development and pathology of the hyaloid, choroidal and retinal vasculature. Int J Dev Biol. 2004;48:1045–58. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041895ms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stahl A, Connor KM, Sapieha P, Chen J, Dennison RJ, Krah NM, et al. The mouse retina as an angiogenesis model. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:2813–26. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito M, Yoshioka M. Regression of the hyaloid vessels and pupillary membrane of the mouse. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1999;200:403–11. doi: 10.1007/s004290050289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lang R, Lustig M, Francois F, Sellinger M, Plesken H. Apoptosis during macrophage-dependent ocular tissue remodelling. Development. 1994;120:3395–403. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.12.3395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meeson A, Palmer M, Calfon M, Lang R. A relationship between apoptosis and flow during programmed capillary regression is revealed by vital analysis. Development. 1996;122:3929–38. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dorrell MI, Aguilar E, Friedlander M. Retinal vascular development is mediated by endothelial filopodia, a preexisting astrocytic template and specific R-cadherin adhesion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3500–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fruttiger M. Development of the mouse retinal vasculature: angiogenesis versus vasculogenesis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:522–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:417–27. doi: 10.1038/nrd3455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature. 2011;473:298–307. doi: 10.1038/nature10144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stone J, Itin A, Alon T, Pe’er J, Gnessin H, Chan-Ling T, et al. Development of retinal vasculature is mediated by hypoxia-induced vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression by neuroglia. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4738–47. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04738.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weidemann A, Krohne TU, Aguilar E, Kurihara T, Takeda N, Dorrell MI, et al. Astrocyte hypoxic response is essential for pathological but not developmental angiogenesis of the retina. Glia. 2010;58:1177–85. doi: 10.1002/glia.20997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLeod DS, Lutty GA, Wajer SD, Flower RW. Visualization of a developing vasculature. Microvasc Res. 1987;33:257–69. doi: 10.1016/0026-2862(87)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan-Ling T, McLeod DS, Hughes S, Baxter L, Chu Y, Hasegawa T, et al. Astrocyte-endothelial cell relationships during human retinal vascular development. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:2020–32. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flower RW, McLeod DS, Lutty GA, Goldberg B, Wajer SD. Postnatal retinal vascular development of the puppy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1985;26:957–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLeod DS, Hasegawa T, Prow T, Merges C, Lutty G. The initial fetal human retinal vasculature develops by vasculogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:3336–47. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Libby RT, Champliaud MF, Claudepierre T, Xu Y, Gibbons EP, Koch M, et al. Laminin expression in adult and developing retinae: evidence of two novel CNS laminins. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6517–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-17-06517.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morissette N, Carbonetto S. Laminin alpha 2 chain (M chain) is found within the pathway of avian and murine retinal projections. J Neurosci. 1995;15:8067–82. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08067.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Byström B, Virtanen I, Rousselle P, Gullberg D, Pedrosa-Domellöf F. Distribution of laminins in the developing human eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:777–85. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YN, Radner S, French MM, Pinzón-Duarte G, Daly GH, Burgeson RE, et al. The γ3 chain of laminin is widely but differentially expressed in murine basement membranes: expression and functional studies. Matrix Biol. 2012;31:120–34. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stenzel D, Franco CA, Estrach S, Mettouchi A, Sauvaget D, Rosewell I, et al. Endothelial basement membrane limits tip cell formation by inducing Dll4/Notch signalling in vivo. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:1135–43. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong S, Landfair J, Balasubramani M, Bier ME, Cole G, Halfter W. Expression of basal lamina protein mRNAs in the early embryonic chick eye. J Comp Neurol. 2002;447:261–73. doi: 10.1002/cne.10245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halfter W, Dong S, Balasubramani M, Bier ME. Temporary disruption of the retinal basal lamina and its effect on retinal histogenesis. Dev Biol. 2001;238:79–96. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Halfter W, Dong S, Dong A, Eller AW, Nischt R. Origin and turnover of ECM proteins from the inner limiting membrane and vitreous body. Eye (Lond) 2008;22:1207–13. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halfter W, Dong S, Schurer B, Osanger A, Schneider W, Ruegg M, et al. Composition, synthesis, and assembly of the embryonic chick retinal basal lamina. Dev Biol. 2000;220:111–28. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Halfter W, Dong S, Schurer B, Ring C, Cole GJ, Eller A. Embryonic synthesis of the inner limiting membrane and vitreous body. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2202–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarthy PV, Fu M. Localization of laminin B1 mRNA in retinal ganglion cells by in situ hybridization. J Cell Biol. 1990;110:2099–108. doi: 10.1083/jcb.110.6.2099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dong LJ, Chung AE. The expression of the genes for entactin, laminin A, laminin B1 and laminin B2 in murine lens morphogenesis and eye development. Differentiation. 1991;48:157–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1991.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Libby RT, Xu Y, Selfors LM, Brunken WJ, Hunter DD. Identification of the cellular source of laminin beta2 in adult and developing vertebrate retinae. J Comp Neurol. 1997;389:655–67. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971229)389:4<655::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alpy F, Jivkov I, Sorokin L, Klein A, Arnold C, Huss Y, et al. Generation of a conditionally null allele of the laminin alpha1 gene. Genesis. 2005;43:59–70. doi: 10.1002/gene.20154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miner JH, Li C, Mudd JL, Go G, Sutherland AE. Compositional and structural requirements for laminin and basement membranes during mouse embryo implantation and gastrulation. Development. 2004;131:2247–56. doi: 10.1242/dev.01112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki T, Fukai N, Mann K, Göhring W, Olsen BR, Timpl R. Structure, function and tissue forms of the C-terminal globular domain of collagen XVIII containing the angiogenesis inhibitor endostatin. EMBO J. 1998;17:4249–56. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Colognato-Pyke H, O’Rear JJ, Yamada Y, Carbonetto S, Cheng YS, Yurchenco PD. Mapping of network-forming, heparin-binding, and alpha 1 beta 1 integrin-recognition sites within the alpha-chain short arm of laminin-1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9398–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colognato H, Yurchenco PD. Form and function: the laminin family of heterotrimers. Dev Dyn. 2000;218:213–34. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200006)218:2<213::AID-DVDY1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hering H, Koulen P, Kröger S. Distribution of the integrin beta 1 subunit on radial cells in the embryonic and adult avian retina. J Comp Neurol. 2000;424:153–64. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000814)424:1<153::AID-CNE11>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brem RB, Robbins SG, Wilson DJ, O’Rourke LM, Mixon RN, Robertson JE, et al. Immunolocalization of integrins in the human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:3466–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Claudepierre T, Dalloz C, Mornet D, Matsumura K, Sahel J, Rendon A. Characterization of the intermolecular associations of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex in retinal Müller glial cells. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:3409–17. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.19.3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blank M, Koulen P, Kröger S. Subcellular concentration of beta-dystroglycan in photoreceptors and glial cells of the chick retina. J Comp Neurol. 1997;389:668–78. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971229)389:4<668::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semina EV, Bosenko DV, Zinkevich NC, Soules KA, Hyde DR, Vihtelic TS, et al. Mutations in laminin alpha 1 result in complex, lens-independent ocular phenotypes in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2006;299:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miner JH, Yurchenco PD. Laminin functions in tissue morphogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:255–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.094555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Edwards MM, Mammadova-Bach E, Alpy F, Klein A, Hicks WL, Roux M, et al. Mutations in Lama1 disrupt retinal vascular development and inner limiting membrane formation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7697–711. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.069575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards MM, McLeod DS, Grebe R, Heng C, Lefebvre O, Lutty GA. Lama1 mutations lead to vitreoretinal blood vessel formation, persistence of fetal vasculature, and epiretinal membrane formation in mice. BMC Dev Biol. 2011;11:60. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-11-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heng C, Lefebvre O, Klein A, Edwards MM, Simon-Assmann P, Orend G, et al. Functional role of laminin α1 chain during cerebellum development. Cell Adh Migr. 2011;5:480–9. doi: 10.4161/cam.5.6.19191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ichikawa-Tomikawa N, Ogawa J, Douet V, Xu Z, Kamikubo Y, Sakurai T, et al. Laminin α1 is essential for mouse cerebellar development. Matrix Biol. 2012;31:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Méhes E, Czirók A, Hegedüs B, Vicsek T, Jancsik V. Laminin-1 increases motility, path-searching, and process dynamism of rat and mouse Muller glial cells in vitro: implication of relationship between cell behavior and formation of retinal morphology. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2002;53:203–13. doi: 10.1002/cm.10062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wuestefeld R, Chen J, Meller K, Brand-Saberi B, Theiss C. Impact of vegf on astrocytes: analysis of gap junctional intercellular communication, proliferation, and motility. Glia. 2012;60:936–47. doi: 10.1002/glia.22325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldberg MF. Persistent fetal vasculature (PFV): an integrated interpretation of signs and symptoms associated with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous (PHPV). LIV Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;124:587–626. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70899-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duh EJ, Yao YG, Dagli M, Goldberg MF. Persistence of fetal vasculature in a patient with Knobloch syndrome: potential role for endostatin in fetal vascular remodeling of the eye. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:1885–8. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(04)00666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cowley M, Conway BP, Campochiaro PA, Kaiser D, Gaskin H. Clinical risk factors for proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1147–51. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020213027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lei H, Rheaume MA, Kazlauskas A. Recent developments in our understanding of how platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and its receptors contribute to proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2010;90:376–81. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Machemer R. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy (PVR): a personal account of its pathogenesis and treatment. Proctor lecture. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988;29:1771–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sethi CS, Lewis GP, Fisher SK, Leitner WP, Mann DL, Luthert PJ, et al. Glial remodeling and neural plasticity in human retinal detachment with proliferative vitreoretinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:329–42. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Manschot WA. Persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous; special reference to preretinal glial tissue as a pathological characteristic and to the development of the primary vitreous. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958;59:188–203. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940030054004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang C, Gehlbach P, Gongora C, Cano M, Fariss R, Hose S, et al. A potential role for beta- and gamma-crystallins in the vascular remodeling of the eye. Dev Dyn. 2005;234:36–47. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rubinstein K. Posterior hyperplastic primary vitreous. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980;64:105–11. doi: 10.1136/bjo.64.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hallmann R, Horn N, Selg M, Wendler O, Pausch F, Sorokin LM. Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:979–1000. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00014.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thyboll J, Kortesmaa J, Cao R, Soininen R, Wang L, Iivanainen A, et al. Deletion of the laminin alpha4 chain leads to impaired microvessel maturation. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:1194–202. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.4.1194-1202.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bredrup C, Matejas V, Barrow M, Bláhová K, Bockenhauer D, Fowler DJ, et al. Ophthalmological aspects of Pierson syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:602–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zenker M, Aigner T, Wendler O, Tralau T, Müntefering H, Fenski R, et al. Human laminin beta2 deficiency causes congenital nephrosis with mesangial sclerosis and distinct eye abnormalities. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2625–32. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dénes V, Witkovsky P, Koch M, Hunter DD, Pinzón-Duarte G, Brunken WJ. Laminin deficits induce alterations in the development of dopaminergic neurons in the mouse retina. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:549–62. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Libby RT, Lavallee CR, Balkema GW, Brunken WJ, Hunter DD. Disruption of laminin beta2 chain production causes alterations in morphology and function in the CNS. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9399–411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09399.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dénes V, Witkovsky P, Koch M, Hunter DD, Pinzón-Duarte G, Brunken WJ. Laminin deficits induce alterations in the development of dopaminergic neurons in the mouse retina. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:549–62. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pinzón-Duarte G, Daly G, Li YN, Koch M, Brunken WJ. Defective formation of the inner limiting membrane in laminin beta2- and gamma3-null mice produces retinal dysplasia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:1773–82. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]