Abstract

Aim

The objective of this study was to identify maternal, obstetrical and reproductive factors associated with long-term changes in maternal weight after delivery.

Materials & methods

Participants were enrolled in a longitudinal cohort study of maternal health 5–10 years after childbirth. Data were obtained from obstetrical records and a self-administered questionnaire. Weight at the time of first delivery (5–10 years prior) was obtained retrospectively and each woman’s weight at the time of her first delivery was compared with her current weight.

Results

Among 948 women, obesity was associated with race, parity, education, history of diabetes and history of cesarean at the time of first delivery. On average, the difference between weight at the time of first delivery and weight 5–10 years later was −11 kg (11 kg weight loss). In a multivariate model, black race and diabetes were associated with significantly less weight loss. Cesarean delivery, parity and breastfeeding were not associated with changes in maternal weight.

Conclusion

Black women and those with a history of diabetes may be appropriate targets for interventions that promote a long-term healthy weight after childbirth.

Keywords: cesarean, obesity, postpartum weight retention

The health risks and economic costs of obesity are a growing public health concern [1]. Currently, more than one-third of adults are obese (defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2) [2]. Among women, obesity is most prevalent among those older than 60 years of age [2] and in minorities [3].

The high prevalence of obesity in women may be, in part, a function of pregnancy, as pregnancy is a time during which a woman’s weight increases considerably. Childbirth is associated with weight increases beyond the term of the pregnancy [4–6]. However, the amount of weight retained after pregnancy is highly variable [7]. Most research examining the impact of pregnancy on postpartum weight has focused on changes in weight in the first year after childbirth. Research on long-term postpartum weight retention is limited [8].

We recently reported that obesity was significantly more prevalent 5–10 years after cesarean than after vaginal birth [9]. This observation led us to question whether long-term changes in weight may differ by route of first delivery. The present study was, therefore, undertaken to investigate whether changes in weight after childbirth differs by route of delivery and to identify factors that influence long-term changes in weight after childbirth.

Materials & methods

This is an analysis of data from the MOAD study, a longitudinal cohort study of maternal health outcomes after cesarean versus vaginal delivery. The study methods have previously been reported [9]. Briefly, MOAD participants were recruited from the obstetrical population at a large community hospital in suburban Maryland (MD, USA). Women were enrolled in the study 5–10 years after their first delivery. Participants were recruited based on the mode of delivery of their first child (cesarean vs vaginal). The recruitment of women in the cesarean and vaginal birth groups was frequency matched to ensure that age at the time of first delivery and years since that delivery were similar between the two groups. Exclusion criteria (applied to the index birth) included: maternal age of <15 or >50 years, delivery at <37 weeks gestation, placenta previa, multiple gestation, known fetal congenital anomaly, stillbirth, prior myomectomy and abruption. Women who experienced these events during subsequent pregnancies were not excluded. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board and all participants provided written informed consent.

At study enrollment, weight was measured by research staff on a balance scale. Height was also measured and BMI was calculated (weight/height2 in kg/m2). Due to the retrospective design of this analysis, weight and other characteristics assessed at the MOAD study enrollment are referred to as occurring at follow-up.

Maternal weight at the conclusion of the first pregnancy was obtained from each participant’s obstetrical chart. While maternal weight at hospital admission is recorded by nursing staff, the value recorded is typically self-reported by the patient at the time of admission. Nevertheless, because obstetrical patients are weighed every week in the last month of pregnancy, the recorded weights are presumed to be timely and accurate.

A list of maternal characteristics hypothesized to be associated with long-term maternal weight change was identified a priori. The independent variable of primary interest was mode of delivery for each woman’s first birth (e.g., cesarean vs vaginal birth). This, and all other obstetrical variables, were abstracted from the hospital record by members of our research team who are also obstetricians. The obstetrical variables of interest included maternal age at first delivery, history of diabetes prior to the first delivery (including gestational diabetes) and the baby’s birth weight (kg).

Data collected at enrollment included: self-reported primary race (black race vs all other races), smoking history (current, former or never), educational attainment (less than college degree, college degree or graduate degree), parity and gravidity. In addition, for each delivery reported, the participant was asked whether she breastfed and if so, the duration of breast-feeding for each delivery (months). The average number of months of lactation per delivery was calculated as the total months of breastfeeding divided by the number of deliveries for each participant.

The first outcome considered was obesity at follow-up, defined as a BMI >30 kg/m2. Demographic and obstetrical history characteristics were summarized using median and inter-quartile range (IQR) for continuous variables, and percentage and frequency for categorical variables. Differences between obese and non-obese women were tested using Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables and χ2-tests of independence for categorical variables.

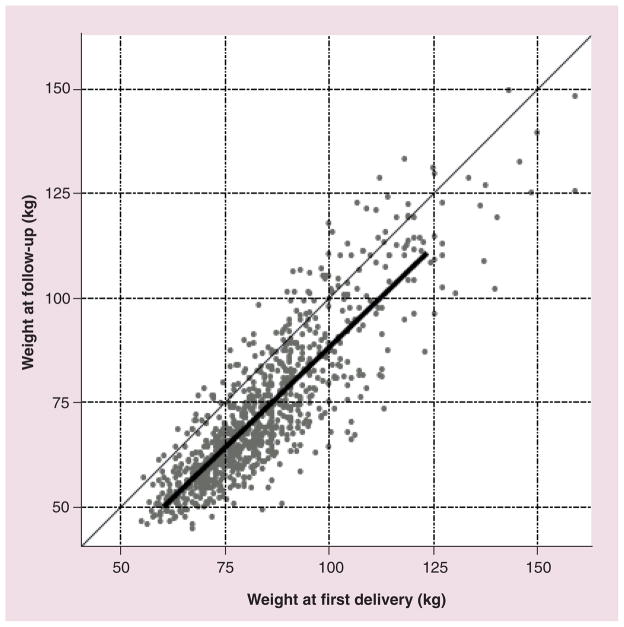

The relationship between each participant’s weight at follow-up and her weight at first delivery (e.g., 5–10 years prior to enrollment) was explored graphically using scatter plot and least-squares linear regression. For each participant, the difference between follow-up weight and weight at first delivery was calculated. Most women lost weight over the 5–10 years from their first delivery. Thus, most values for change in weight had negative values.

Univariate linear regression was used to identify factors associated with change in weight. The characteristics significantly associated with change in weight were further investigated in multivariate analysis. Where necessary, piecewise linear models were developed to address nonlinear relationships. Final multivariate linear regression models were determined using Akaike Information Criterion [10]. Because our primary goal for this analysis was to explore the possible effect of cesarean versus vaginal delivery on maternal weight change, a variable reflecting the mode of first delivery was retained in all models.

All analysis was performed using SAS 9.2© statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA, 2002–2008). Graphical figures were created using S-Plus 8.0© statistical software (Insightful Corp., WA, USA, 2007). Statistical significance was defined at the α = 0.05 level.

Results

At the time of analysis, the MOAD study included 1011 participants. Of these, 52 women (5%) were excluded from the analysis because maternal weight at first delivery was not available. An additional 11 women were excluded as outliers because they either lost more than 40 kg (n = 8) or gained more than 20 kg (n = 3). Finally, 43 women who had delivered their last child within 12 months of enrollment were excluded. Thus, 905 women were included in this analysis. Among these women, median weight at follow-up was 73 kg (IQR: 60–81) and 24% of participants were obese at follow-up. The median age at follow-up was 40 years (IQR: 36–43) and the median duration of time between first childbirth and follow-up was 7.4 years (IQR: 6.4–9.0).

Demographic and obstetrical history characteristics of the 905 women, overall and by obesity status at follow-up, are shown in Table 1. Obesity was strongly associated with a history of cesarean birth. Specifically, only 24% of obese women versus 48% of nonobese women delivered their first child vaginally (p < 0.001). Obesity at the time of study enrollment was also strongly associated with weight at the time of first delivery (p < 0.001). Other characteristics associated with obesity include black race, lower educational attainment, diabetes during the first pregnancy and lower parity. Obese women were less likely to have breastfed and reported fewer total months of breastfeeding. Finally, obese women were also slightly younger at the time of their first birth and the weight of their first baby was slightly higher.

Table 1.

Demographic and obstetrical characteristics† of the study population, overall and by obesity status at follow-up (n = 905).

| Characteristic | Overall (n = 905) | Obesity status at follow-up

|

p-value‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonobese (BMI ≤30 kg/m2; n = 684) | Obese (BMI >30 kg/m2; n = 221) | |||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| – Black race (%) | 13 (117) | 9 (62) | 25 (55) | <0.01 |

| – Maternal age (years) | 40 (36–43) | 40 (36–43) | 39 (35–43) | 0.06 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status at follow-up | ||||

| – Former§ (%) | 23 (210) | 24 (162) | 22 (48) | 0.10 |

| – Current (%) | 9 (79) | 8 (52) | 12 (27) | |

|

| ||||

| Years between first delivery and follow-up | 7.4 (6.4–9.0) | 7.4 (6.4–8.9) | 7.5 (6.3–9.3) | 0.83 |

|

| ||||

| Maternal educational attainment | ||||

| – Less than college degree (%) | 23 (206) | 18 (125) | 37 (81) | <0.01 |

| – College degree (%) | 43 (392) | 44 (304) | 40 (88) | |

| – Graduate degree (%) | 34 (307) | 37 (255) | 24 (52) | |

|

| ||||

| Change in weight from first delivery (kg) | −11.4 (−16.4 to −6.0) | −12.7 (−17.3 to −9.0) | −3.6 (−10.4 to 2.7) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Characteristics of first pregnancy | ||||

| – Maternal age at first delivery (years) | 32 (29–36) | 32 (29–36) | 31 (27–35) | 0.03 |

| – Maternal weight at first delivery (kg) | 81 (73–91) | 77 (71–84) | 99 (90–112) | <0.01 |

| – Diabetes/gestational diabetes at first delivery (%) | 4 (36) | 2 (15) | 10 (21) | <0.01 |

| – Birth weight of first child (kg) | 3.44 (3.15–3.76) | 3.40 (3.13–3.72) | 3.51 (3.20–3.83) | 0.01 |

| – Vaginal first delivery (%) | 42 (379) | 48 (325) | 24 (54) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Other reproductive factors | ||||

|

| ||||

| Parity (at follow-up) | ||||

| – 1 (%) | 29 (260) | 25 (171) | 40 (89) | <0.01 |

| – 2 (%) | 55 (501) | 57 (390) | 50 (111) | |

| – 3+ (%) | 16 (144) | 18 (123) | 10 (21) | |

|

| ||||

| Gravidity | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 3 (2–4) | 0.63 |

|

| ||||

| Multiple birth, ever (%) | 2 (22) | 3 (18) | 2 (4) | 0.49 |

|

| ||||

| Breastfed first child (%) | 72 (655) | 75 (514) | 64 (141) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Ever breastfed any child (%) | 77 (693) | 80 (545) | 67 (148) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Average duration of lactation at each delivery¶# (months) | 9 (5–13) | 10 (6–13) | 7 (4–13) | <0.01 |

Median (interquartile range) or percentage (frequency).

Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables; χ2-tests for categorical variables.

Former smoker defined as having smoked >100 cigarettes in a lifetime, but not currently a smoker.

Among women who reported breastfeeding with at least one child (n = 693).

Women who were missing average duration of lactation (n = 27). correlation (r2 = 0.75) between weight at first delivery and follow-up weight, further analysis focused on factors influencing the difference between these two values.

The strong association between weight at first delivery and follow-up weight is illustrated in Figure 1. Mean change in weight was −11.1 kg (11.1 kg weight loss). Due to the strong correlation (r2 = 0.75) between weight at first delivery and follow-up weight, further analysis focused on factors influencing the difference between these two values.

Figure 1. Maternal weight at follow-up (kg) versus maternal weight at first delivery (kg; n = 905).

Least-squares linear regression (solid line) is defined as weight at follow-up = −72.91 + (0.96 × [weight at first delivery − 84]).

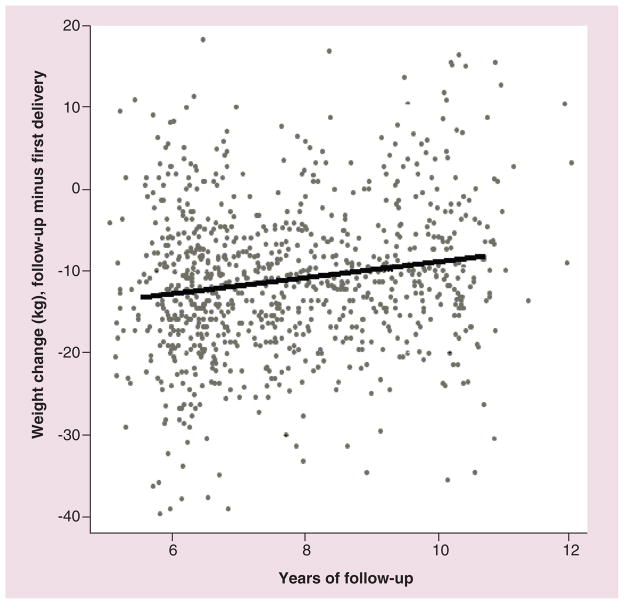

Univariate linear regression was used to investigate characteristics associated with change in weight between first delivery and follow-up (Table 2). Because greater weight loss is indicated by a more negative number, the negative coefficients in Table 2 indicate greater weight loss. Thus, factors significantly associated with greater weight loss include greater maternal weight at the time of first delivery, greater weight of the infant at first delivery, multiparity and greater educational attainment. In addition, an association between weight change and maternal age at first delivery was noted, but this association was not linear: weight loss was least at the extremes of maternal age. Thus, the relationship between change in weight and maternal age at first delivery was modeled as two piecewise linear values: ≤ 30 years and >30 years of age. Black women experienced significantly less weight loss than women of other races. In addition, weight loss was attenuated with increasing time between first birth and study enrollment. This relationship is shown graphically in Figure 2. There was no significant association between change in weight and cesarean or vaginal birth (p = 0.20). A post-hoc power analysis indicated that there was sufficient power to observe a difference in weight change of 1.6 kg between the cesarean and vaginal birth groups.

Table 2.

Change in maternal weight (from first delivery to study enrollment) as a function of demographic, obstetric and reproductive risk factors (n = 905).

| Independent variable | Unadjusted

|

Adjusted

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | Estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Maternal weight at first delivery | −0.04 (−0.07–0.00) | 0.04 | −0.04 (−0.08–0.00) | 0.03 |

|

| ||||

| Maternal age at first delivery | ||||

| – ≤30 years (per 1 year) | −0.67 (−0.96 to −0.39) | <0.01 | −0.60 (−0.89 to −0.32) | <0.01 |

| – >30 years (per 1 year) | 0.20 (0.02–0.38) | 0.03 | 0.15 (−0.03–0.34) | 0.10 |

|

| ||||

| Years of follow-up (per 1 year) | 0.97 (0.60–1.33) | <0.01 | 1.04 (0.68–1.39) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Diabetes/gestational diabetes at first delivery | 2.85 (−0.11–5.82) | 0.06 | 3.53 (0.65–6.40) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||

| Birth weight of first child (per 1 kg) | −2.28 (−3.52 to −1.04) | <0.01 | −1.70 (−2.96 to −0.45) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| First delivery: vaginal (vs cesarean) | 0.77 (−0.41–1.95) | 0.20 | 0.30 (−0.85–1.45) | 0.61 |

|

| ||||

| Multiparous at follow-up (vs primiparous) | −1.75 (−3.03 to −0.48) | <0.01 | −1.34 (−2.67 to −0.01) | 0.05 |

|

| ||||

| Race: black (vs other races) | 3.78 (2.06–5.49) | <0.01 | 3.26 (1.52–5.01) | <0.01 |

|

| ||||

| Maternal educational attainment at follow-up: college or more (vs less than college) | −1.90 (−3.28 to −0.52) | <0.01 | – | – |

|

| ||||

| Smoking status at follow-up | ||||

| – Former (vs never) | −0.78 (−2.17–0.62) | 0.28 | – | – |

| – Current (vs never) | −0.86 (−2.94–1.23) | 0.42 | – | – |

|

| ||||

| Successfully breastfed ever (vs never) | −1.25 (−2.62–0.12) | 0.07 | – | – |

|

| ||||

| Average duration of lactation per delivery†‡ | ||||

| – ≤6 months (vs 6–12 months) | 1.27 (−0.34–2.88) | 0.12 | – | – |

| – >12 months (vs 6–12 months) | 0.35 (−1.24–1.95) | 0.66 | – | – |

Restricted to women who reported successfully initiating breastfeeding with at least one child (n = 693).

Women who were missing average duration of lactation (n = 27).

– Not applicable.

Figure 2. Maternal weight change (follow-up weight minus weight at the time of first delivery; kg) versus years of follow-up (n = 905).

Least-squares linear regression (solid line) is defined as weight change = −11.29 + 0.97 × (years of follow-up −7.5).

These variables were candidates for the multivariate analysis and the most parsimonious adjusted model is shown in Table 2. Greater maternal weight at the time of first delivery and greater weight of the neonate were both associated with greater weight loss between first delivery and follow-up. Controlling for these factors, history of diabetes or gestational diabetes at the first delivery and black race were both associated with less weight loss over follow-up. Specifically, compared with nondiabetic women, women who were diabetic at the conclusion of the first pregnancy lost, on average, 3.53 kg less over follow-up. Average weight loss among black women was 3.26 kg less than that in nonblack women. Among women aged 30 years or younger at the time of first birth, older age at first birth was significantly associated with greater weight loss; conversely, among those over the age of 30 years, older age at first birth was associated with slightly less weight loss over follow-up. Finally, the time between first delivery and follow-up was inversely associated with change in weight. As noted, there was no significant association between change in weight and cesarean or vaginal birth.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to investigate whether the very strong association observed between cesarean and obesity later in life could be attributed to route of delivery (e.g., whether that association was independent of the possible difference between women who deliver by cesarean). Although women who delivered by cesarean were more likely to be obese 5–10 years from delivery, this association was not significant after accounting for other differences, most notably weight at the time of first childbirth. Obesity during pregnancy is known to be associated with cesarean birth [11] and our results suggest that mode of delivery has no effect on long-term changes in maternal weight. Maternal weight at the time of a first delivery is a strong predictor of weight 5–10 years later and the long-term weight trajectory is similar for women who deliver by cesarean and vaginal birth.

An important finding from this research is the substantial impact of race on changes in maternal weight. This finding is consistent with prior research, but extends such research by controlling for the confounding effects of diabetes, maternal weight during pregnancy, breastfeeding practices and maternal education [4,6,12–14]. Furthermore, prior studies of race and weight retention have been limited by the use of self-reported, retrospectively recalled weights, limited follow-up time, or other population constraints [12–14]. For example, a 10-year prospective cohort study found that black women had a much greater chance of becoming overweight after childbirth, but utilized retrospectively recalled pregravid weights [15]. Findings by Gunderson and colleagues suggested that the increased odds of becoming overweight for black mothers was explained by differences in parity and pregravid obesity [5]. However, these findings suggest that racial differences persist after adjustment. Gunderson has suggested that weight gain among black women may reflect differences in social, cultural and behavioral factors. Given the high prevalence of obesity in black women, it is important to better understand the causes that may contribute to greater postpartum weight in this population [1,3].

Another striking finding from the present study was the impact of diabetes. After controlling for maternal weight at first delivery and the weight of the neonate, the participants with gestational diabetes or pregestational diabetes retained significantly more weight than those who were not exposed to diabetes before delivery. This effect persisted after controlling for the confounding effect of weight at the time of delivery. Unfortunately, we did not have a sufficient sample to investigate possible differences between gestational and pregestational diabetes on long-term weight change. The extra weight retained by mothers with a history of gestational diabetes may indicate continued insulin resistance, which may exacerbate the risk for Type 2 diabetes if not controlled [16].

In this cohort, additional deliveries (after the first) contributed marginally to long-term maternal weight. Specifically, multiparous women lost more weight than primiparous women (although this association was marginally significant in a multivariate model). Prior studies have demonstrated inconsistent results regarding the impact of multiparity on maternal weight, with some suggesting no association between parity and weight [4,5,17] and others suggesting an association between increasing maternal weight with additional pregnancies [18,19].

No association between breastfeeding and changes in maternal weight was found. This is somewhat surprising because breastfeeding has been associated with short-term weight loss after childbirth [20]. In fact, women are often advised to breastfeed as a strategy to promote weight loss after delivery. However, the literature is conflicting and inconsistent regarding the benefits of breastfeeding on long-term maternal weight [15,16,21,22]. Some research has suggested that the recommended dietary caloric allowance for lactating women is too high and that greater caloric intake coupled with a more sedentary lifestyle may explain why weight loss with lactation is highly variable [4].

The finding in this study that weight increases with length of follow-up supports current literature [17]. However, this association is unlikely related to childbirth, since weight tends to increase with age [17].

While this study had a strong focus on reproductive factors, it was limited by data regarding lifestyle, including exercise and dietary practices, which could have important influence on weight. Also, an inherent limitation of this study is the lack of data regarding prepregnancy weight and gestational weight gain. Many prior studies of long-term changes in weight after pregnancy have focused on the impact of gestational weight gain, but the impact of gestational weight gain in this population cannot be commented on [15–18,21]. In addition, the impact of unmeasured differences between women who delivered vaginally and those who delivered by cesarean cannot be excluded. Last, a limitation of this research is that the population in this study was highly educated and was somewhat older at first delivery than would be typical for US women. These characteristics may limit the generalizability of the results, especially with respect to teenage mothers and less affluent populations.

A strength of this study is the relatively large population size. With a sample size of almost 1000 women, this cohort facilitated an examination of a variety of potential risk factors related to long-term weight. Also, the focus on reproductive factors allowed for an assessment of parity, breastfeeding and mode of delivery while controlling for obesity at delivery. Another strength of this analysis is that maternal weight at first delivery was recorded prospectively and is, therefore, not subject to potential recall bias. Also, the use of obstetrical records for reproductive data (including baby birth weights) is more likely to provide valid exposure data than maternal recall.

Conclusion

This study provided a unique opportunity to examine long-term changes in maternal weight 5–10 years after pregnancy. The findings of this research have important implications for the clinical care of obstetrical patients. Specifically, our results suggest that efforts to prevent obesity should be targeted at black women and women with diabetes. Women with these characteristics may be appropriate targets for educational, behavioral and nutritional interventions that promote the return to a long-term healthy weight after pregnancy.

Future perspective.

With increasing obesity worldwide, efforts to help adults maintain a healthy weight become more critical. Given the limited effectiveness of most weight-loss interventions, prevention of obesity is critical. Our research suggests that black women and women with gestational diabetes may be ideal populations to target for obesity prevention trials.

Executive summary.

Maternal weight at the time of first delivery is a strong predictor of weight 5–10 years later, with an average change in weight of −11 kg.

Over 5–10 years from the time of first delivery, black women and women with diabetes lost less weight compared with women without these characteristics.

After a first delivery, long-term changes in maternal weight were not influenced by cesarean versus vaginal birth (although women who deliver by cesarean are more likely to be heavier at the time of birth and 5–10 years later). Breastfeeding did not influence long-term change in maternal weight.

Footnotes

Ethical conduct of research

The authors state that they have obtained appropriate institutional review board approval or have followed the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for all human or animal experimental investigations. In addition, for investigations involving human subjects, informed consent has been obtained from the participants involved.

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Support was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD056275). The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Ford ES, Li C, Zhao G, et al. Trends in obesity and abdominal obesity among adults in the United States from 1999–2008. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35:736–743. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2••.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. NCHS Data Brief. 82. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD, USA: 2012. Prevalence of Obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. National statistics from the USA suggest that obesity affects a third of US adults, with the highest rates of obesity in women over 60 years of age. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lester CR, et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295:1549–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crowell DT. Weight change in the postpartum period: a review of the literature. J Nurse Midwifery. 1995;40:418–423. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(95)00049-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5••.Gunderson EP. Childbearing and obesity in women: weight before, during and after pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36:317–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.04.001. Summarizes relevant literature regarding both pregravid weight and gestational weight gain as predictors of later obesity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gore SA, Brown DM, West DS. The role of postpartum weight retention in obesity among women: a review of the evidence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26:149–159. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Olsen CM, Strawderman MS, Hinton PS, et al. Gestational weight gain and postpartum behaviors associated with weight change from early pregnancy to 1 y postpartum. Int J Obes. 2003;27:117–127. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8••.Schmitt NM, Nicholson WK, Schmitt J. The association of pregnancy and the development of obesity – results of a systematic review and meta-analysis on the natural history of postpartum weight retention. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007;31:1642–1651. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803655. The authors conclude that the published literature suggests that most parturients lose weight in the first-year postpartum and regain weight over time. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handa VL, Blomquist JL, Knoepp LR, Hoskey KA, McDermott KC, Muñoz A. Pelvic floor disorders 5–10 years after vaginal or cesarean childbirth. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(4):777–784. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182267f2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automatic Control. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 11••.Poobalan AS, Aucott LS, Gurung T, Smith WC, Bhattacharya S. Obesity as an independent risk factor for elective and emergency caesarean delivery in nulliparous women – systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Obes Rev. 2009;10(1):28–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00537.x. Concludes that the odds of cesarean birth (either elective or emergent) are increased by 50% in overweight women and by >100% in obese women. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keppel KG, Taffel SM. Pregnancy-related weight gain and retention, implications of the 1990 Institute of Medicine guidelines. Am J Public Health. 1993;83:1100–1103. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Wise LA, et al. A prospective study of the effect of childbearing on weight gain in black women. Obes Res. 2003;12:1526–1535. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parker JD, Abrams B. Differences in postpartum weight retention between black and white mothers. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:768–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunderson EP, Abrams B, Selvin S. The relative importance of gestational gain and maternal characteristics associated with the risk of becoming overweight after pregnancy. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1660–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rooney BL, Schauberger CW, Mathiason MA. Impact of perinatal weight change on long-term obesity and obesity-related illness. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1349–1356. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000185480.09068.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Billewicz WZ, Thomson AM. Body weight in parous women. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1970;24:97–104. doi: 10.1136/jech.24.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson DF, Madans J, Pamuk E, et al. A prospective study of childbearing and 10-year weight gain in US white women 25–45y of age. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994;18:561–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weng HH, Bastian LA, Taylor DH, Jr, et al. Number of children associated with obesity in middle-aged women and men, results from the health and retirement study. J Womens Health. 2004;13:85–91. doi: 10.1089/154099904322836492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker JL, Gamborg M, Heitmann BL, Lissner L, Sørensen TI, Rasmussen KM. Breastfeeding reduces postpartum weight retention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1543–1551. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amorim AR, Rossner S, Neovius M, et al. Does excess pregnancy weight gain constitute a major risk for increasing long-term BMI? Obesity. 2007;15:1278–1286. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rookus MA, Rokebrand P, Burema J, et al. The effect of pregnancy on the body mass index 9 months postpartum in 49 women. Int J Obes. 1987;11:609–618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]