Abstract

Itch of peripheral origin requires information transfer from the spinal cord to the brain for perception. Here, primate spinothalamic tract (STT) neurons from lumbar spinal cord were functionally characterized by in vivo electrophysiology to determine the role of these cells in the transmission of pruriceptive information. One hundred eleven STT neurons were identified by antidromic stimulation and then recorded while histamine and cowhage (a nonhistaminergic pruritogen) were sequentially applied to the cutaneous receptive field of each cell. Twenty percent of STT neurons responded to histamine, 13% responded to cowhage, and 2% responded to both. All pruriceptive STT neurons were mechanically sensitive and additionally responded to heat, intradermal capsaicin, or both. STT neurons located in the superficial dorsal horn responded with greater discharge and longer duration to pruritogens than STT neurons located in the deep dorsal horn. Pruriceptive STT neurons discharged in a bursting pattern in response to the activating pruritogen and to capsaicin. Microantidromic mapping was used to determine the zone of termination for pruriceptive STT axons within the thalamus. Axons from histamine-responsive and cowhage-responsive STT neurons terminated in several thalamic nuclei including the ventral posterior lateral, ventral posterior inferior, and posterior nuclei. Axons from cowhage-responsive neurons were additionally found to terminate in the suprageniculate and medial geniculate nuclei. Histamine-responsive STT neurons were sensitized to gentle stroking of the receptive field after the response to histamine, suggesting a spinal mechanism for alloknesis. The results show that pruriceptive information is encoded by polymodal STT neurons in histaminergic or nonhistaminergic pathways and transmitted to the ventrobasal complex and posterior thalamus in primates.

Keywords: dorsal horn, pain, thalamus, histamine, cowhage

chronic pruritus is often associated with neuropathy, skin disease, and organ dysfunction. Many clinically relevant forms of pruritus are inadequately controlled by antihistamines, and effective alternatives are lacking (Ikoma et al. 2006; Yosipovitch et al. 2004). The recent identification of multiple and distinct neural pathways for itch, including histamine-independent pathways, suggests that novel targets may exist for the control of pruritus (Davidson and Giesler 2010). However, the neural pathways involved in both histaminergic and nonhistaminergic itch remain poorly understood. Moreover, the degree to which the sensation of itch is processed distinctly, or can be targeted separately, from pain is unresolved.

Spinal cord projection neurons with axons that ascend within the anterolateral funiculus are required for the perception of itch, because lesion of these tracts eliminates itch caused by both histaminergic and nonhistaminergic pruritogens (Bickford 1938; Hyndman and Wolkin 1943). Among the ascending tracts of the anterolateral funiculus, the spinothalamic tract (STT) responds to pruritogens with activation that reflects the time course of itch sensation in humans (Andrew and Craig 2001; Davidson et al. 2007; Simone et al. 2004). Furthermore, the response of STT neurons to histamine is inhibited by scratching the skin, demonstrating a neural correlate of scratch-induced relief and pointing to the importance of spinal processing in the control of itch (Davidson et al. 2009). In addition to activation by pruritogens, STT neurons are also excited by various noxious stimuli. This is similar to pruritogen-responsive primary afferent nociceptors (Johanek et al. 2008; Ringkamp et al. 2011; Schmelz et al. 2003). The polymodal functionality of the peripheral and central neural pathways involved in pruriception is at odds with the idea that itch sensation is produced by a distinct subgroup of serially connected neurons excited only by pruritic stimuli (i.e., a “labeled line”). However, an alternative to the labeled line hypothesis has not been demonstrated. Among the possibilities proposed to contribute to the neural discrimination of itch and pain are specialized discharge patterns of primary afferent fibers (Johanek et al. 2008), differing roles of peptidergic versus glutamatergic signaling at the first synapse (Carstens et al. 2010; Langerstrom et al. 2010; Liu et al. 2010), and spinal neural population coding (Akiyama et al. 2009a; Davidson et al. 2007).

As the target of the STT, the thalamus receives and processes somatosensory information, but its specific role in the discrimination of pruriceptive signals is unclear. The somatotopic organization of the thalamus provides a substrate for representing stimulus localization on the body (Jones 2008). However, an additional layer of organization based on topographic representation of modality could provide a substrate for the discrimination of different types of somatosensory stimuli (Patel et al. 2006; Zhang et al. 2006). To determine the precise anatomical sites within the primate thalamus that receive sensory information associated with itch, we used antidromic mapping to localize axon terminations of pruritogen-responsive STT neurons. Neurons were functionally characterized by their responses to the following stimulus modalities: mechanical, thermal, noxious chemical (capsaicin), and pruritic (both histaminergic and nonhistaminergic). Central sensitization was examined after the response to a pruritogen to determine whether alloknesis may occur through a spinal mechanism similar to that described for allodynia (Simone et al. 1991, 2004).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal preparation.

Monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) between 2.5 and 10 kg were used in accordance with protocols approved by the institutional review board of the University of Minnesota. Monkeys were sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg im) and catheterized at the cephalic vein. Pentobarbital sodium (20 mg/kg iv) produced a depth of anesthesia sufficient for intubation. α-Chloralose (65 mg/kg iv) was administered slowly over an hour. The monkey was placed on a feedback-controlled heating pad and fixed in the prone position onto a stereotaxic frame. A mixture of pentobarbital sodium (3–10 mg·kg−1·h−1), the paralytic gallamine triethiodide (Flaxedil; 5–14 mg·kg−1·h−1), and physiological saline was delivered intravenously continuously by adjustable-rate pump. The monkey was artificially ventilated, and CO2 was monitored continuously along with arterial blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature. Pneumothoraces were placed to reduce movement of the spinal cord. A laminectomy was performed over the lumbar enlargement, a bilateral craniotomy (interaural 0–20 mm rostral and from the midline to 15 mm lateral) exposed the cortex over both thalami, and the dura was retracted. The spinal cord was covered with warm mineral oil, and the brain was covered with a mixture of mineral oil and petroleum jelly.

Antidromic mapping technique.

The antidromic method is advantageous because it avoids sampling bias introduced by search criteria such as mechanical or chemical sensitivity. To locate the ventral posterior lateral nucleus (VPL), a low-impedance recording electrode was placed into the thalamus (initial coordinates: interaural +8.0 mm, midline +8.0 mm, depth from cortical surface −18.0 mm) in search of neurons activated by tactile stimulation of the contralateral body. Once VPL was somatotopically mapped and its caudal boundary identified (i.e., the most caudal coordinate at which activity could be recorded from mechanical stimulation of the hindlimb), the electrode was repositioned 2 mm caudal, 2–3 mm medial, and 1–2 mm ventral from that point. This location was presumed to be within the posterior thalamus. With the electrode in place, the headstage was replaced by the cathode from a stimulus isolator; the anode, in contact with the monkey, was grounded. A second stimulating electrode was positioned in caudal VPL, within the area most responsive to mechanical stimulation of the hindlimb. Once both stimulating electrodes were positioned, a repeating square wave (“search stimulus”: 5 Hz, 200 μs, 500 μA) was delivered through both electrodes, allowing for the stimulation of a wide area of the posterior thalamus and caudal VPL. During search stimulation, an Epoxylite-insulated stainless steel recording electrode (∼10 MΩ) was inserted through a perforation in the spinal pia-arachnoid and into the dorsal horn. The recording electrode was repositioned in the dorsal horn until an action potential was observed meeting the criteria for antidromic activation: constant latency from stimulation, ability to follow a >300-Hz train, and demonstrative collision between an orthodromic and an antidromic action potential (Lipski 1981). The two stimulating electrodes were then alternately switched off to determine which provided the stimulus for the antidromic action potential. Often, antidromic action potentials could be generated by both the VLP and posterior thalamus stimulating electrodes. In this situation the more rostral VPL electrode typically generated action potentials with longer latency than the electrode located in the posterior thalamus, indicating that the axon likely passed through the posterior thalamus en route to VPL. Few STT axons project more rostral than VPL. Action potentials generated by the search stimulus in the posterior thalamus that could not initially be antidromically activated by the VPL electrode were investigated further by moving the VPL electrode medially and laterally from the initial position in 500-μm increments across the thalamus. At each new position the stimulating electrode was lowered ventrally in 400-μm steps while the recording was continuously monitored for the identified antidromic action potential. If no antidromic action potential could be generated within the mediolateral plane, the VPL electrode was moved 1 mm caudal and a new mediolateral plane was mapped as described above. This procedure was repeated until an antidromic action potential was reliably established, or, if none could be established even in caudal planes with the VPL electrode, then antidromic mapping was continued with the electrode in the posterior thalamus. At each new thalamic position where an antidromically activated action potential was established, the stimulus amplitude was lowered to such a level that action potentials were generated at only a 50% success rate. This “threshold” amplitude of current was recorded and the electrode then repositioned to determine the current thresholds surrounding the axon. The most rostral position at which antidromic action potentials could be generated by ≤30 μA was named the low threshold point (LTP). This amplitude has been demonstrated to activate only axons that are within 400 μm of the tip of the stimulating electrode (Burstein et al. 1991; Ranck 1975; Zhang et al. 1999). The termination zone of an STT axon was defined as an LTP surrounded in three dimensions by current pulses above 500 μA that failed to generate antidromic action potentials (Davidson et al. 2008).

Mechanical and thermal characterization.

For each STT neuron, the location, size, and shape of the receptive field were determined with mechanical stimulation. Graded mechanical sensitivity was tested during brushing of the receptive field with a soft bristled brush, pressure applied with an arterial clip, and pinch with a smaller, painful arterial clip. Cells that did not respond to these mechanical stimuli were tested further with a more intense stimulus, squeezing the skin with large forceps. Cells were classified as either high threshold (HT; those that did not respond to innocuous stimuli) or wide dynamic range (WDR; those that responded both to innocuous stimuli and, at higher frequencies, to more intense mechanical stimuli). Thermal stimuli were applied to the receptive field with a contact thermal probe (9 × 9-mm surface area; Yale Instruments). Stimuli of 40°C, 45°C, and 50°C were applied at a rate of 3°C/s from a holding temperature of 30°C. All thermal stimuli were held at the test temperature for 5 s. For some cells only the 50°C stimulus was applied. Subsequent trials were begun after >90 s and only after ongoing activity returned to baseline levels. A cell was considered responsive if the mean firing rate during the 5-s test temperature was at least 150% of the baseline ongoing activity. Baseline activity was calculated as the mean firing rate during the 20 s before the heat stimulus.

STT neurons were examined for sensitization to mechanical stimuli by comparing the discharge to mechanical stimuli before and at least 10 min after activation by a pruritic agent and when ongoing activity returned to baseline. Receptive fields were 1) stroked with a cotton-tipped swab that was mounted on a flexible metal holder (4-cm stroke length in 1 direction through the receptive field), 2) poked with a 100-mN von Frey-like monofilament with a 200-μm tip at four sites within the receptive field, and 3) pricked with a 50-μm punctuate stimulus that was mounted on a monofilament probe that delivered a force of 20 mN (Sikand et al. 2009). Each mechanical stimulus lasted 2 s and was repeated four times, and the responses were averaged. Baseline activity during the 10 s immediately prior to the stimulus application was subtracted from the stimulus-evoked activity to obtain the response.

Pruritic and algogenic stimuli.

Histamine dihydrochloride (20 μg in 10 μl of 0.9% saline), pH 5.0, or a pH-matched vehicle (saline) was delivered intradermally through a 28-gauge needle (Simone et al. 2004). In initial experiments, cowhage was applied by pressing an entire pod onto the receptive field, leaving 50–100 trichomes inserted in the skin. Later, cowhage was plucked from the pod and inserted into a cotton-tipped swab so that the distal tip of each trichome pointed out. Approximately 20 trichomes were applied by dabbing the swab against the skin. Cowhage was rendered inactive by placing the pod in an autoclave for 20 min. Inactive cowhage was applied in the same manner in which active cowhage was applied. Autoclaved (inactive) cowhage does not produce itch, but the structural integrity of the trichomes is maintained (Sikand et al. 2009). Every cell received each of the four treatments, with the vehicle always preceding histamine and the inactive cowhage always preceding the active cowhage. Four equidistant points were marked within the mechanically identified receptive field, and each control or pruritogen application occurred near one of these points. Subsequent stimuli were applied to an area of skin that was free of a bleb or wheal caused by a previous injection. The order of presentation of vehicle/histamine and inactive/active cowhage was randomized. Trichomes from active and inactive cowhage were removed from the skin after the test with a piece of low-tack paper tape. A minimum of 20 min was taken between stimulus applications. STT neurons were considered responsive to an itch-producing agent when the rate of action potentials 1) increased at least 150% from the mean ongoing baseline discharge rate and 2) outlasted any response to the control stimulus by at least 60 s. STT neurons were tested for sensitivity to an intradermal injection of capsaicin (10 μg in 10 μl of 7% Tween 80 in normal saline) with a 28-gauge needle after testing with pruritic agents. Analog voltage recordings were amplified, filtered (10–30 kHz), digitized at 33 kHz, and then waveform discriminated and saved on a PC with custom DAPSYS software (www.dapsys.net).

Histology.

At the end of each experiment, an electrolytic lesion was made at the LTP in the thalamus (15 μA, 45 s) and at the recording point in the spinal cord (25 μA, 20 s). Monkeys were perfused with 1 liter of cold normal saline and then with 3 liters of 10% formalin with 1% ferrocyanide to produce a Prussian blue reaction at the locations of the lesions. The brain and spinal cord were removed and placed in 10% formalin-1% ferrocyanide overnight and then blocked the next day. Sections were cut on a freezing microtome in 75-μm or 50-μm sections for the brain and spinal cord, respectively. The tissue was stained with neutral red, and the sites of the lesions made at the tip of the electrode were identified. All thalamic nuclei were identified in histological sections by location, intensity of staining, size and orientation of cells, and the pattern of fibers passing through the area. The nomenclature for the macaque thalamus in this study was derived from Jones (2008). The atlases of macaque brains at Brainmaps.org (Mikula et al. 2007) were used as supplemental guides.

Data analyses.

Stimulation intensity maps for antidromic thresholds were superimposed over tracings of thalamic sections by using the lesion marking the LTP as an anchor point and the distance between track marks and the track mark orientation as guides. Color contour plots of the current threshold at each stimulation point were generated with SigmaPlot v. 10.0 (Systat Software). Measures of the variability in spike trains were assessed by using spike time data beginning 30 s after the application of histamine, cowhage, and capsaicin. This was to limit the mechanically evoked activity associated with the application of the stimulus, and to avoid possible latent periods before activity evoked by pruritogens reached the response criteria. Spike times over the following 3 min were used to analyze the spike train; however, for a few cells data up to only 2 min were used because the receptive field was manipulated by the experimenter. The coefficient of variation (CV) was calculated for each pruritogen-responsive STT neuron. CV is the standard deviation of interspike intervals (ISIs) divided by the mean duration of ISIs within a spike train. All statistical analyses were performed with paired or unpaired Student's t-tests, ANOVA, or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate.

RESULTS

In adult macaques, 111 STT neurons were identified by antidromic stimulation from the contralateral thalamus and tested for responses to mechanical and chemical stimuli applied to the skin; 91 of these neurons were also tested for responses to thermal stimuli. Each primate STT neuron responded to mechanical stimulation of its receptive field; 29.7% were classified as HT, and 69.4% were classified as WDR. A single neuron in this study responded to innocuous brushing but not to noxious pinch and was classified as a low-threshold type. The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage were applied to the receptive field of STT neurons in pseudorandom order subsequent to the application of their control (i.e., vehicle for histamine or inactivated cowhage spicules). We found that 20.0% (22/110) of STT neurons were activated by histamine and 12.8% (14/109) were activated by cowhage. There was little overlap in the histamine-responsive and cowhage-responsive subsets of STT neurons. Of pruritogen-responsive STT neurons only 5.5% (2/36) responded to both pruritic agents.

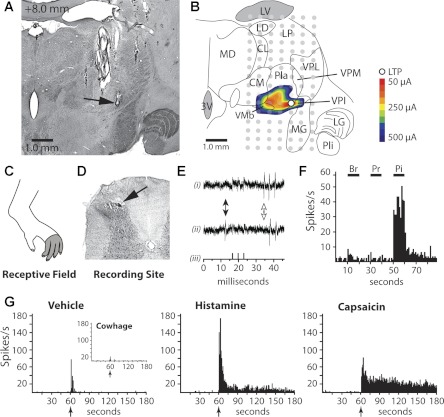

The zone of axon termination within the contralateral thalamus was determined by surrounding the most rostral antidromic stimulation site (i.e., the LTP) in three dimensions with current pulses >500 μA that failed to elicit antidromic action potentials. An example of an LTP surrounded by sites of antidromic current pulses is shown in Fig. 1, A and B. This axon projected from a histamine-responsive STT neuron recorded in the contralateral marginal zone and had a receptive field over four toes of the hindlimb (Fig. 1, C and D). The LTP was determined histologically to be within the ventral posterior inferior nucleus (VPI). The LTP was surrounded (mediolaterally, dorsoventrally, and rostrally) by stimulation points at which 500-μA pulses were unable to elicit antidromic action potentials, indicating that the axon did not extend outside of the identified zone. Three stimulating pulses delivered at the LTP in the thalamus evoked three action potentials recorded in the spinal cord, each with a latency of 14.0 ms, indicating an estimated conduction velocity of 15.7 m/s (Fig. 1E). The neuron was further examined for responses to mechanical stimuli applied to the receptive field and was classified as HT (Fig. 1F). There was no response to a 50°C cutaneous heating stimulus (not shown). Next the neuron was tested for evoked activity in response to an intradermal injection of vehicle and then of histamine (20 μg in 10 μl). Histamine evoked a discharge >150% of baseline activity for longer than 60 s compared with the vehicle injection (Fig. 1G). No such discharge was seen after cowhage spicules were applied to the skin (Fig. 1G, inset). Injection of capsaicin evoked a robust and long-lasting discharge (Fig. 1G).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of a histamine-responsive spinothalamic tract (STT) neuron with an axon termination in ventral posterior inferior nucleus (VPI). A: section of thalamus containing the lesion (arrow) marking the furthest rostral low threshold point (LTP) (+8.0 mm rostral of interaural plane). B: illustration of the section in A showing the location of each antidromic test site (gray dot). The minimum current amplitude required to elicit antidromic action potentials is shown by a color contour plot. Outside of the contour plot antidromic stimulation did not elicit action potentials. C: receptive field. D: lesion marking the recording site in the superficial dorsal horn (SDH) (arrow). E: antidromic action potentials (i) follow high-frequency triple stimulation (iii) and demonstrate collision (ii; absence of 1st spike of the triplicate, white arrow) when an ascending orthodromic action potential occurs (black arrow). F: responses to mechanical stimulation [brush (Br), pressure (Pr), pinch (Pi)] of the receptive field. G: application of cowhage produced no activation, and intradermal injection of vehicle produced some activation during the injection, but the cell returned quickly to baseline. Injection of histamine produced a large initial discharge and a long-lasting period of activity. Capsaicin also activated the cell. Arrows indicate time of injection/application. 3V, 3rd ventricle; CL centrolateral n.; CM, centromedian n.; LD, lateral dorsal n.; LG, lateral geniculate; LP, lateral posterior n.; LV, lateral ventricle; MD, mediodorsal n.; MG, medial geniculate; Pla, anterior pulvinar; PLi, inferior pulvinar; VMb, basal ventromedial n.; VPM, ventral posterior medial n.; VPL, ventral posterior lateral n.

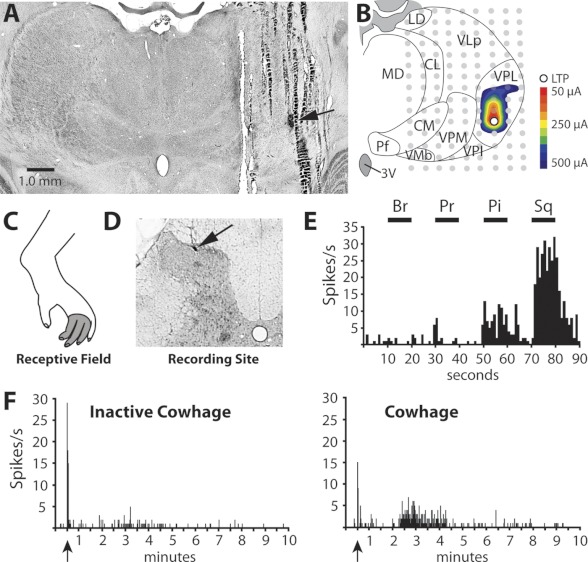

An example of an STT neuron that responded to cowhage is shown in Fig. 2. The LTP (Fig. 2, A and B) was surrounded in the rostral, mediolateral, and dorsoventral planes by stimulation sites that failed to produce antidromic action potentials, indicating the zone of axon termination to be within the VPL nucleus. This HT cell, located in the superficial dorsal horn (SDH), was responsive to noxious, but not innocuous, cutaneous mechanical stimulation applied to the receptive field (Fig. 2, C–E). The response to cowhage began after a latent period, and the elevated activity lasted for ∼2 min (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of a cowhage-responsive STT neuron with an axon projection to VPL. A: section of thalamus containing the lesion marking the LTP (arrow). B: illustration of the same section showing antidromic thresholds in a color contour plot. C: receptive field. D: lesion marking the recording site in the SDH (arrow). E: mechanical sensitivity; the cell was classified as high threshold (HT). Sq, squeeze. F: application of inactivated cowhage produced little or no activation, but active cowhage evoked 2 min of activity after a latency period.

Histamine-responsive STT neurons.

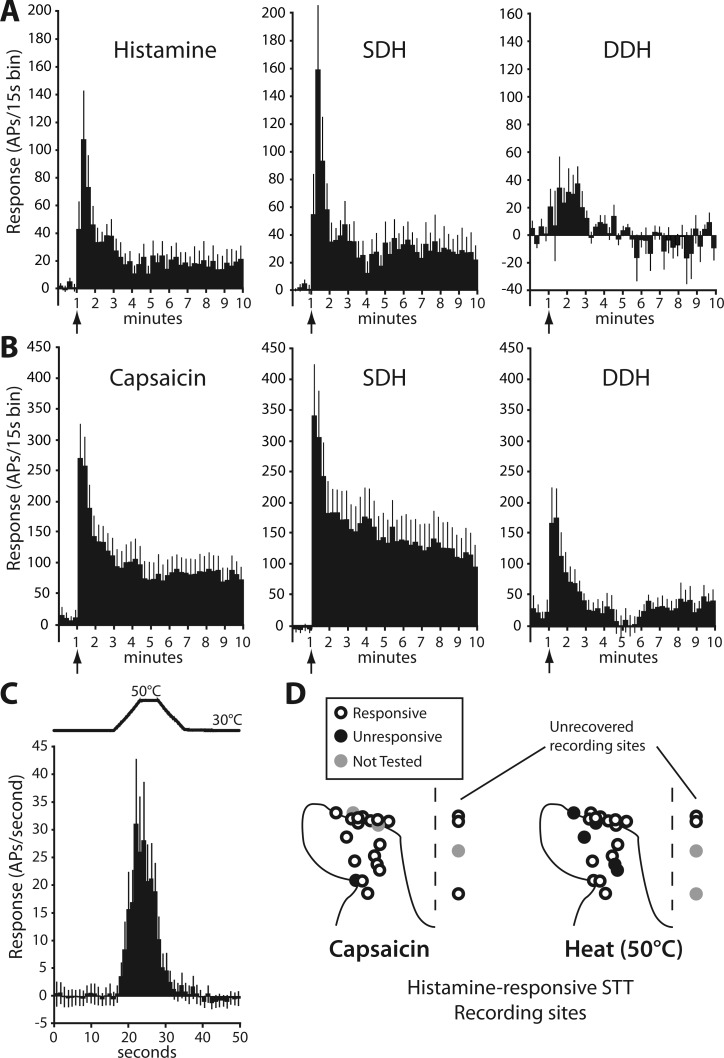

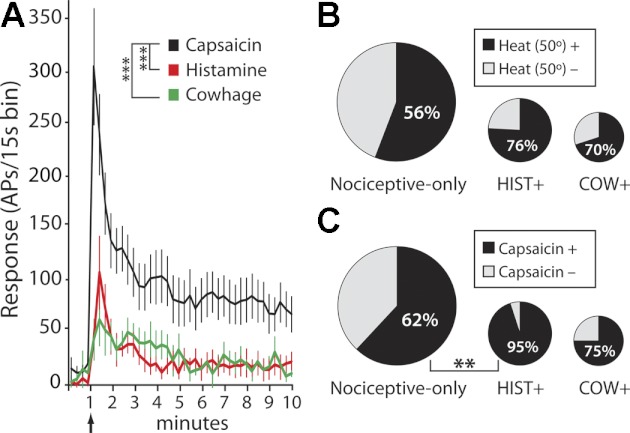

STT neurons responsive to histamine were found both in the SDH (13/22) and within the nucleus proprius and lateral reticulated area of the deep dorsal horn (DDH; 9/22). Of SDH-located histamine-responsive STT neurons, 46% were classified as HT and 54% were WDR. Of those located in the DDH, 22% were HT and 78% were WDR. Baseline activity of histamine-responsive STT neurons was 2.44 ± 0.90 spikes/s (range 0–18.7 spikes/s). No difference was detected between the baseline firing rates of SDH and DDH neurons (P = 0.63, t-test). The mean response of 15 histamine-responsive STT neurons to an intradermal injection of histamine is shown in a peristimulus time histogram in Fig. 3A; 8 units were omitted from this analysis because their receptive fields were manipulated during the response. For each neuron, the ongoing activity during vehicle was subtracted from the discharge evoked by histamine to give the response profile. The contribution to the overall histamine response by SDH STT neurons and DDH STT neurons is shown in Fig. 3A. These data illustrate the substantial relative contribution of SDH neurons in generating both the initial peak response during the first minute and the sustained response that persisted longer than 10 min. In contrast, neurons in the DDH appeared to contribute only during the first minutes after injection. Intradermal capsaicin evoked a discharge in 19 of 20 (95%) histamine-responsive STT neurons; the mean response of 14 units is shown in Fig. 3B. Five units were omitted from this analysis because their receptive fields were manipulated during the response. Of histamine-responsive STT neurons, 75% responded to a 5-s, 50°C heat stimulus with a mean response of 22.5 ± 7.6 Hz during stimulus plateau (Fig. 3C). The spinal location of each recorded histamine-responsive STT neuron and its sensitivity to capsaicin and heat are shown in Fig. 3D.

Fig. 3.

Functional characterization of histamine-responsive STT neurons. A: response to histamine (vehicle activity subtracted) is shown in 15-s bins (n = 15). Cells recorded in the SDH account for most of the robust initial response and all of the persistent activity [SDH: n = 10, deep dorsal horn (DDH): n = 5]. AP, action potential. B: response to capsaicin in histamine-responsive STT neurons (SDH: n = 7, DDH, n = 7). C: mean response to a 50°C heat ramp in heat-responsive/histamine-responsive STT neurons (n = 16). D: locations of each histamine-responsive STT neuron profiled by heat and capsaicin activation. Lesion sites marking cells to right of dashed line were unrecovered, and position was estimated by recording depth from the surface of the spinal cord.

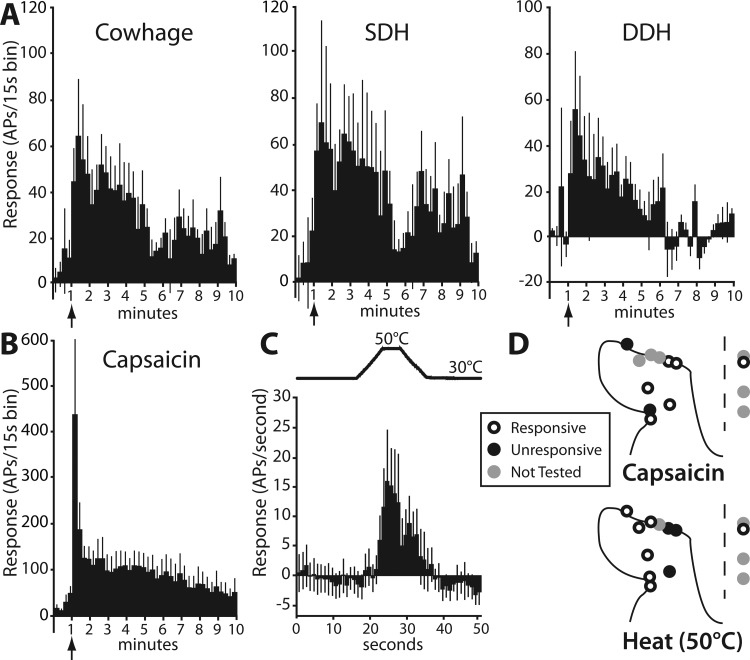

Cowhage-responsive STT neurons.

STT neurons responsive to cowhage were found both in the SDH (9/14) and within the DDH (5/14). Of the superficially located cowhage-responsive STT neurons, 44% were classified as HT and 56% were WDR. Of cells located in the DDH, all five were classified as WDR. Mean baseline activity of cowhage-responsive STT neurons was 3.5 ± 1.2 spikes/s (range 0.13–13.5 spikes/s) and did not differ between SDH and DDH neurons (P = 0.32; t-test). The mean response to cowhage is shown in a peristimulus time histogram along with the relative contributions by the SDH and DDH subsets of STT neurons in Fig. 4A. Similar to the response profile for SDH histamine-responsive STT neurons, cowhage-responsive SDH neurons accounted for a greater proportion of initial activity, and all of the discharge beyond 5 min. A latent period after cowhage application of ∼30 s was observed in 7 of 14 cowhage-responsive STT neurons (see, e.g., Fig. 2E). Intradermal capsaicin evoked a discharge in six of eight cowhage-responsive STT neurons, and the mean response is shown in Fig. 4B. Of cowhage-responsive STT neurons, 70% responded to a 5-s, 50°C heat stimulus with a mean response of 10.2 ± 6.4 spike/s (Fig. 4C). This was not different from the response to heat in histamine-responsive STT neurons (P = 0.32, t-test). The spinal location of each cowhage-responsive STT neuron recorded and its capsaicin and heat sensitivity are shown in Fig. 4D.

Fig. 4.

Functional characterization of cowhage-responsive STT neurons. A: response to cowhage (inactive activity subtracted) is shown in 15-s bins (n = 11) and sorted by SDH (n = 6) and DDH (n = 5). B: mean capsaicin discharge over time (combined SDH and DDH, n = 4). C: mean response to a 50°C heat ramp in heat-responsive/cowhage-responsive STT neurons (n = 7). D: locations of each cowhage-responsive STT neuron and heat and capsaicin profiles.

Pruriceptive and nociceptive activation.

The discharge produced by histamine in histamine-responsive STT neurons was compared against the discharge produced by cowhage in cowhage-responsive neurons. Additionally, the response to pruritogens was compared against the response to capsaicin (Fig. 5). Baseline activity was not different between histamine-responsive and cowhage-responsive STT neurons (P = 0.48, t-test). The capsaicin-evoked discharge was not different between histamine and cowhage responders in any bin throughout the time course of the recorded response (2-ANOVA), and the data were pooled in further analyses. As shown in Fig. 5A, the mean response to capsaicin was significantly larger than the response to either of the pruritogens (2-ANOVA, Tukey posttest, P < 0.001 vs. histamine-responsive, P < 0.001 vs. cowhage-responsive neurons). The overall discharge rate evoked by histamine versus cowhage was not different, despite the fact that the responses were from nearly exclusive cell populations (based on the pruritic response) and were evoked by different stimuli. All pruritogen-responsive STT neurons responded to noxious mechanical stimulation and were classified as nociceptive. All pruritogen-responsive neurons responded to capsaicin or to heat, and a majority responded to both (Fig. 5, B and C). The proportion of STT neurons responsive to capsaicin was significantly larger in the histamine-responsive subset than in the nociceptive-only population (Fisher's exact test, P < 0.01). The proportion of heat-responsive STT neurons was not different between any groups.

Fig. 5.

Pruritogen-responsive STT neurons are a subset of nociceptive STT neurons. A: peristimulus time histogram showing time course of response to histamine (n = 15), cowhage (n = 11), and capsaicin (n = 18) in pruriceptive STT neurons. The discharge from capsaicin was significantly greater than the discharge from either histamine or cowhage (***P < 0.001, 2-ANOVA), which were not different from each other. B and C: area of each circle is proportional to the size of each STT subpopulation indicated. Of the total STT population nociceptive-only cells represent 67%, histamine+ represent 20%, and cowhage+ represent 13%. Pie charts indicate % of STT neurons from each subpopulation that were responsive to a 50°C heat ramp (B) or capsaicin (C) (**P < 0.01, Fisher's exact test).

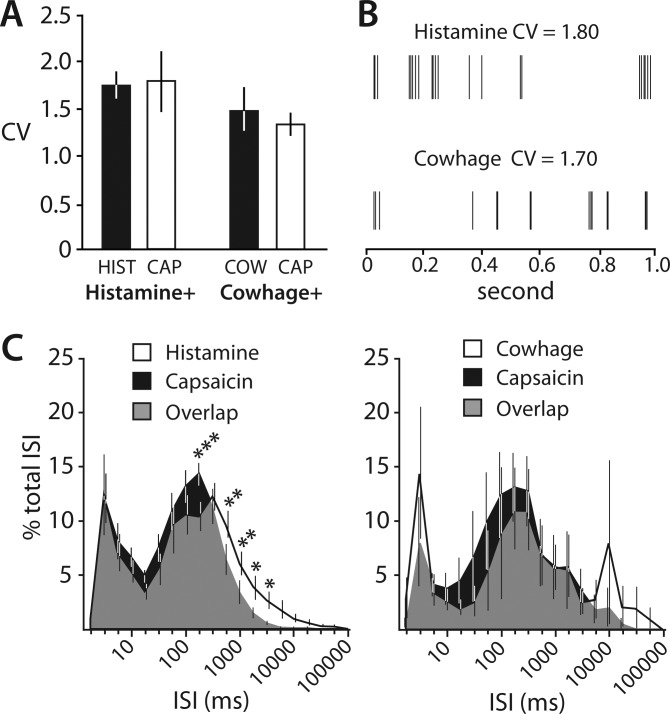

Spike train analyses.

An analysis of the variability of ISIs was performed to determine whether histamine and cowhage produced different spike timing dynamics, and whether differences in spiking patterns could be detected between pruritic and noxious stimuli. The variability of ISIs was assessed for each spike train by using the CV (Fig. 6A). The mean CV during the response to histamine (1.74 ± 0.13) was not different from the CV during the response to cowhage (1.47 ± 0.22) (P = 0.28, unpaired t-test). Within groups, the CV during the response to a pruritogen did not differ from the CV during the response to capsaicin. The high degree of variability in spike timing, indicated by CV values well over 1, reflects an irregular discharge pattern. Indeed, spike trains for both the histamine- and cowhage-responsive subsets of STT neurons showed bursting behavior, i.e., a series of short-latency spikes (intraburst) followed by a period of quiescence (interburst; Fig. 6B). To further characterize the discharge pattern, normalized ISI distribution histograms were generated for histamine- and cowhage-responsive STT neurons (Fig. 6C). For these plots, ISIs from each spike train were sorted into 20 log-scaled bins and the number of ISIs contained within each bin was divided by the total number of ISIs over the spike train. The ratio in each bin was multiplied by 100 to obtain percentage, and mean percent/bin was calculated from all responders. ISIs generated during the response to pruritogens were distributed bimodally, indicating a prevalence of bursting. Peak ISIs clustered around short intervals (intraburst < 10 ms) and longer intervals (100 < interburst < 600 ms). The distribution of ISIs generated by the response to capsaicin was also bimodal. However, a leftward shift in the distribution of “interburst” ISIs occurred in the histamine-responsive subset during the capsaicin response, indicating that capsaicin produced ISIs with significantly shorter interburst intervals.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of spike timing in pruritogen-responsive STT neurons. A: the level of the coefficient of variation (CV) of interspike intervals (ISIs) indicates an irregular discharge pattern for pruriceptive STT neurons. The variability is not different between histamine and cowhage or between pruritogen and capsaicin. B: sample of representative spike trains from 1 cowhage- and 1 histamine-responsive STT neuron showing the typical bursting pattern of AP firing. C: normalized ISI distribution histograms. Bimodal peaks indicate that histamine, cowhage, and capsaicin evoke discharges that exhibit bursting behavior. Capsaicin discharge possesses significantly shortened interburst duration compared with histamine (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, 2-ANOVA, Tukey posttest).

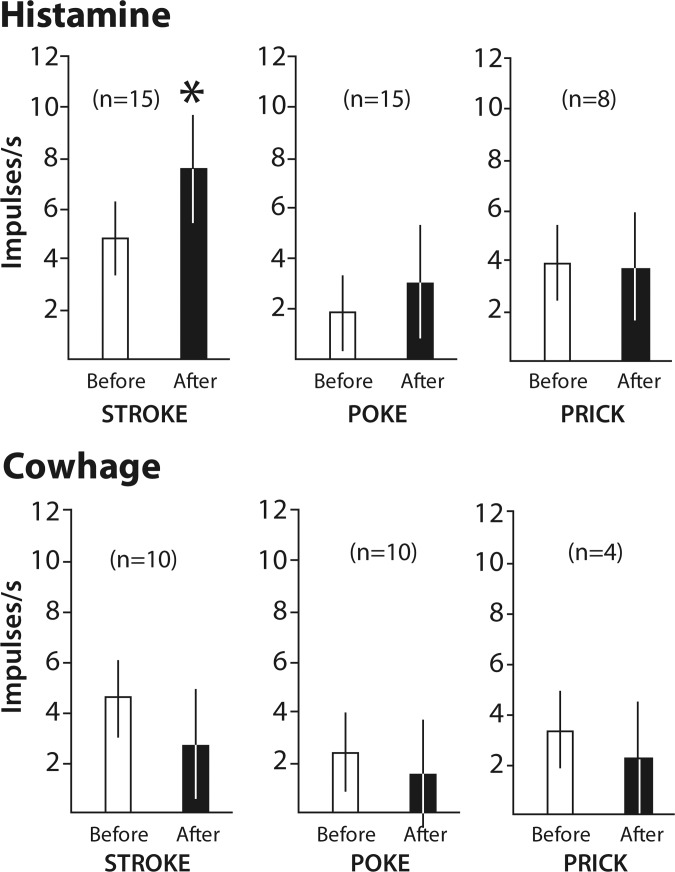

Neural correlate of pruritic dysesthesia.

Dysesthesias such as a rekindling of itch can sometimes be evoked with mechanical stimuli applied to an area that was previously itchy (Sikand et al. 2009; Simone et al. 1991). After each control agent and pruritogen were delivered, STT neurons were examined for changes in response to mechanical stimuli to determine whether any hypersensitivity could be detected. Hypersensitivity was assessed with a cotton-tipped swab that was gently stroked across the receptive field, a von Frey-like monofilament that was poked against the skin within the receptive field, and a pricking stimulus. Activity induced by stroking in histamine-responsive STT neurons was significantly enhanced after the response to histamine compared with the responses to stroking after the vehicle (Fig. 7). All other mechanical stimuli generated responses after the pruritogen that were similar to the responses after the vehicle or inactive application.

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity to mechanical stimuli before and after a response to a pruritogen. Stroking the receptive field with a cotton-tipped swab evoked a greater discharge after a histamine response than before the histamine response (*P < 0.05, paired t-test). Other mechanical stimuli elicited no change in discharge after a response to histamine or cowhage.

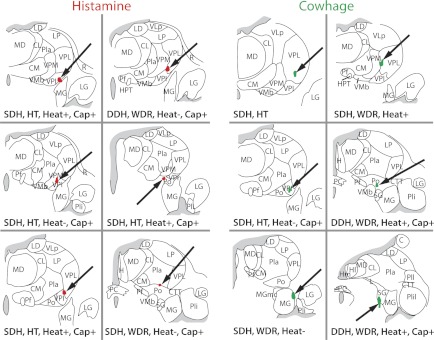

Termination zones.

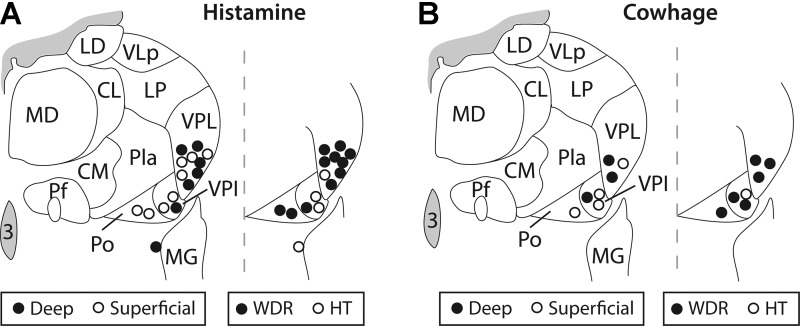

Axon termination zones within the contralateral thalamus were completely mapped by microantidromic stimulation for six histamine-responsive and six cowhage-responsive STT neurons. All histamine-responsive STT neurons were found to terminate within a band of nuclei located within the posterior and ventrobasal complex of the thalamus. These nuclei included the posterior (Po), the VPI, and the VPL. Cowhage-responsive STT neurons possessed axons that were tracked to the same nuclei as histamine-responsive axons, with the addition of termination zones located in the suprageniculate and medial geniculate nuclei. The identified zone of axon termination for each completely surrounded LTP is shown in Fig. 8, and the functional characterization of each cell is indicated. Incompletely surrounded LTPs indicate the location of an axon projection, and may reflect either an axon of passage or a zone of termination. The locations of incompletely surrounded LTPs are illustrated in Fig. 9, with the spinal location and mechanical sensitivity of each associated STT neuron indicated. Although no nucleus within primate thalamus could be classified as an “itch projection center,” axons of pruritogen-responsive STT neurons were most often tracked to the VPL nucleus (15/34, 44%), suggesting a prominent role for VPL in the processing of pruritic information.

Fig. 8.

Zones of termination of pruriceptive STT neurons: antidromically mapped and completely surrounded projection targets of 6 histamine-responsive and 6 cowhage-responsive subsets of STT neurons. Termination zones were located in the ventrobasal complex and posterior thalamus. Anatomical and functional classifications for each STT neuron are indicated. WDR, wide dynamic range.

Fig. 9.

LTPs (<30 μA) within the thalamus for antidromically activated pruritogen-responsive STT neurons. Projections from pruritogen-responsive STT neurons were found in VPL, VPI, and posterior nucleus (Po). Anatomical and mechanical classifications are indicated.

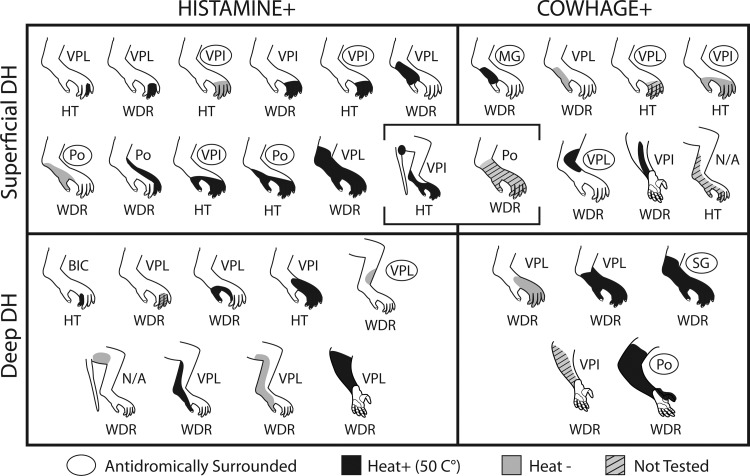

Receptive fields.

The cutaneous receptive field of each pruritogen-responsive STT neuron is illustrated in Fig. 10. Receptive fields ranged in size from one digit to most of the hindlimb. Neurons in the DDH possessed a higher proportion of larger receptive fields. The thalamic projection target associated with each receptive field is noted, as is the sensitivity to heat and mechanical stimuli.

Fig. 10.

Receptive fields of each pruritogen-responsive STT neuron with mechanical and heat-response classification indicated. Projection target is indicated, and completely surrounded LTPs are circled.

DISCUSSION

A lack of understanding of the complex neural systems responsible for itch may have impeded the development of new treatments for pruritus, which continue to be based primarily on antihistamines (Thurmond et al. 2008). Intractable pruritus might be overcome by therapy directed at mechanisms of nonhistaminergic itch, which was recently recognized to be largely propagated by distinct primary afferent fibers and spinal neurons (Davidson et al. 2007; Johanek et al. 2007; Namer et al. 2008; reviewed in Davidson and Giesler 2010). In this study we anatomically and functionally tested STT neurons for sensitivity to histamine or the nonhistaminergic pruritogen cowhage and mapped their projection targets within the thalamus. Our results demonstrate that distinct subsets of polymodal primate STT neurons transmit information from histaminergic or nonhistaminergic itch-producing stimuli to the contralateral ventrobasal complex (VPL and VPI) and posterior nucleus (Po). Axons from cowhage-responsive STT neurons were additionally found to terminate in suprageniculate and medial geniculate nuclei, suggesting the possibility of a broader target area for nonhistaminergic pruriceptive projections.

A recent imaging study showed that histamine- and cowhage-induced itch produced overlapping but distinguishable patterns of forebrain activation (Papoiu et al. 2012). In the thalamus, cowhage-induced itch was suggested to have produced more extensive activation than histamine-induced itch, consistent with the present antidromic mapping data. Both cowhage and histamine predominantly elicit the sensation of itch, but other concomitant sensations blend with the overall sensation (Sikand et al. 2009). Subjects who rated a set of attributes describing their sensory experience reported that cowhage produced more “stinging,” “sharp,” and “prickly” sensations than histamine (Kosteletzky et al. 2009). These distinct sensations may be related to the additional areas of activation within the thalamus associated with cowhage-induced itch. Observation of the pattern of neural activation evoked by additional recently identified histamine-independent itch mediators chloroquine, BAM8–22, and cathepsin-S (Liu et al. 2009; Reddy et al. 2010; Sikand et al. 2011) could narrow the neural regions commonly activated by all pruritogens.

The extent of overlap in the forebrain for modalotopic representation of nociceptive and pruriceptive sensations is unclear. A degree of shared neuroanatomy between itch and pain is suggested by similar burning and stinging parathesias that are reported by poststroke central neuropathic itch and neuropathic pain patients (Shapiro and Braun 1987; Yosipovitch et al. 2004). The thalamus is integral for somatosensory processing, and while thalamic activation in humans was detected after the induction of itch in some imaging studies (Herde et al. 2007; Leknes et al. 2007; Mochizuki et al. 2003; Valet et al. 2008), it was below the threshold for detection in others (Drzezga et al. 2001; Hsieh et al. 1994). A test of the hypothesis that the magnitude of thalamic activity differed between itch and pain confirmed that histamine-evoked itch produced significantly less thalamic activation than an equally intense pain stimulus (Mochizuki et al. 2007). The idea that itch and pain are transmitted by shared pathways but pruritic stimuli evoke less neural activity than nociceptive stimuli is consistent with the present results in which histamine or cowhage evoked significantly less activity than the painful chemical capsaicin within the same STT neuron. Additionally, brief noxious mechanical and thermal stimuli consistently evoked higher discharge rates in pruriceptive STT neurons than pruritic agents. Our data suggest that the lower metabolic activity observed in the thalamus during itch may be a result of both the modest proportion of pruriceptive STT neurons and the lower activity of these neurons when stimulated by pruritogens compared with algogens.

The intensity theory of itch, which postulates that low- or high-intensity firing within a primary sensory neuron generates itch or pain, respectively, has been challenged by evidence from transcutaneous electrical stimulation experiments that have found that altering stimulation frequency does not convert itch to pain (Ikoma et al. 2005; Tuckett 1982). Also, C-fiber discharge patterns in humans did not correlate with itch or pain (Handwerker et al. 1991). The experimental evidence against the intensity theory is focused on primary afferent fibers and does not exclude the possibility of intensity coding in the CNS. Additionally, the possibility of pruriceptive or nociceptive information coded within the timing dynamics of the spike train of spinal neurons is unresolved. Interestingly, in response to histamine and cowhage, peripheral C fibers in the monkey were found to fire in a bursting pattern (Johanek et al. 2008). Here we show that pruriceptive STT neurons fired in a bursting pattern to both pruritogens and also to a subsequent application of capsaicin. The interval between bursts was significantly longer during histamine than during capsaicin, limiting the discharge rate and possibly contributing a direct signal for itch. Interburst intervals during the response to cowhage likewise appeared longer than those during the response to capsaicin, but it is cautioned that this was not significant.

“Itchy skin,” or alloknesis, is itch evoked by gentle mechanical stimulation (Simone et al. 1991). The magnitude and duration of histamine-induced alloknesis develop in a dose-dependent manner (Simone et al. 1991), but alloknesis after cowhage was reported to develop in only ∼50% of trials (LaMotte et al. 2009). Alloknesis was hypothesized to reflect sensitization of pruriceptive spinal neurons. Sensitization of pruriceptive neurons could be a mechanism for some forms of chronic pruritus. Previously, we found a single STT neuron that doubled its discharge to stroking the skin after histamine (Simone et al. 2004). Here we examined the mean response to stroking, a punctuate stimulus, and a pricking stimulus before and after responses to histamine or cowhage. Histamine-responsive (but not cowhage-responsive) STT neurons developed a significantly sensitized response to stroking, but no changes in response to punctuate or pricking stimuli were observed in either type of STT neuron.

All primate pruriceptive STT neurons responded to noxious mechanical and some combination of noxious thermal and chemical stimulation, indicating that they were polymodal chemonociceptive neurons. Pruriceptive STT neurons were found in both the SDH and DDH, but superficially located neurons contributed the bulk of the overall response to each pruritic agent. Previous work in cats showed histamine-responsive SDH STT neurons that were unresponsive to mechanical stimulation and mustard oil, and it was suggested that these cells were selective for itch (Andrew and Craig 2001). This selectivity for histamine may reflect species differences between cats and primates, and may also reflect methodological differences in the testing of adequate mechanical, thermal, and chemical stimuli. In the mouse, spinal and trigeminal neurons with undetermined projections responded to histamine and to the peptide SLIGRL, an activator of the proteinase-activated receptor (PAR)2 that is involved in nonhistaminergic itch. These mouse spinal and trigeminal neurons also responded to noxious thermal and chemical stimuli, indicating their polymodal nature, although a rare neuron was found to be selective for pruritogens (Akiyama et al. 2009a, 2009b, 2010). The majority of spinal neurons in cat and mouse did not respond to pruritic agents. Our results show that two-thirds of primate STT neurons were nonpruriceptive (i.e., nociceptive only), indicating that itch is encoded and transmitted to the brain by a limited subset of spinal neurons. It is possible that other pruritogens such as BAM8–22 or chloroquine, not used in this study, could have activated some of the nonpruriceptive neurons.

The contribution to pain sensation of the subset of pruriceptive spinal neurons is unclear. A group of superficially located pruriceptive spinal neurons in mice was discovered that could be identified by the expression of the gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR) (Sun and Chen 2007). Elimination of the neurons expressing GRPR reduced scratching in mice exposed to various pruritogens, but pain behaviors were not affected (Sun et al. 2009). These results demonstrate the importance of the subset of dorsal horn neurons expressing GRPR for itch-related behavior. The electrophysiological properties of single spinal neurons expressing GRPR have not yet been reported, so it is not known whether they can be activated by nociceptive stimuli. Because the pruriceptive subset of spinal neurons is small compared with the nociceptive-only population, their contribution to nociceptive processing may be difficult to detect.

STT neurons can receive both direct and indirect inputs from primary afferent fibers, some of which are sensitive to pruritic stimuli. Two broad classes of pruriceptors have been described: those that are histamine sensitive and those that are histamine insensitive. Histamine produced activity in a group of mechanically insensitive C fibers that was closely correlated with the itch sensation in humans (Schmelz et al. 1997, 2003). These fibers are thought to be peptidergic because they are crucial for the axon-reflex flare response (Schmelz et al. 2000). Mechanically insensitive C fibers were not activated by cowhage. Instead, cowhage activated mechanically sensitive C fibers, indicating parallel peripheral pathways for histaminergic and nonhistaminergic itch (Namer et al. 2008). Additionally, unlike histamine, cowhage produced only negligible flare, and antihistamines failed to reduce cowhage-induced itch, supporting the idea that cowhage produces itch through a histamine-independent pathway (Johanek et al. 2007). The active itch-producing agent in cowhage, a cysteine protease named mucunain, activates PAR2 and PAR4 receptors (Reddy et al. 2008). An alternative activator of PAR2, the peptide SLIGRL, induced scratching in mice and a discharge in a subset of dorsal horn neurons (Akiyama et al. 2009a, 2009b; Shimada et al. 2006). SLIGRL has also been identified as an activator of MrgprC11, and its activation induced scratching in mice; however, SLIGRL activation of PAR2 appeared to have a role in hyperalgesia and not itch (Liu et al. 2011). Whether, or the extent to which, cowhage/mucunain activates Mrgprs or PARs to produce itch in primates remains to be answered. Recently, in addition to C fibers, mechanically sensitive Aδ-nociceptors were found to be responsive to cowhage and histamine and contributed to the sensation of itch (Ringkamp et al. 2011).

Primary afferent pruriceptors contain “pruritic receptors” such as histamine receptors, PARs, or Mrgprs but also contain “nociceptive receptors” such as TRPV1 (Imamachi et al. 2009; Shim et al. 2007), TRPA1 (Wilson et al. 2011), and bradykinin receptors (Han et al. 2006). Some of these nociceptive receptors have been shown to be critically involved in the cellular responses to a pruritogen. Therefore, it could be expected that spinal neurons responsive to pruritic stimuli would also be responsive to noxious stimuli. Given this polymodality of STT neurons, the finding of distinct subsets of histaminergic and nonhistaminergic STT neurons is surprising. A possible explanation for why histaminergic STT neurons did not respond to cowhage is that peripheral histamine fibers may terminate at a depth in the skin below where cowhage spicules could penetrate. If true, this would suggest the interesting hypothesis that termination depth in the skin of primary afferent fibers guides the central input to distinct subsets of STT neurons. This anatomy may also provide a reason for why intradermal injections of SLIGRL, but not cowhage spicules, could activate spinal neurons responsive to histamine (in addition to the ability of SLIGRL to activate Mrgprs on histamine-responsive sensory neurons). On the other hand, it is probable that intradermal injection of histamine extends into the epidermis where the cowhage-responsive fibers presumably terminate. This suggests that cowhage-responsive fibers, despite being exposed to histamine, do not transmit histaminergic information to the STT.

New ways to alleviate itch could take advantage of the “endogenous” itch control system. Previously, we found that scratching the receptive field inhibited histamine-evoked activity in STT neurons, pointing to a spinal mechanism for the control of itch (Davidson et al. 2009). A candidate inhibitory interneuron that acts to regulate itch was recently identified in the SDH (Ross et al. 2010). Also, blocking GABAergic and glycinergic transmission in the spinal cord blocked scratch-induced inhibition of ongoing activity in dorsal horn neurons from a mouse model of dry skin pruritus (Akiyama et al. 2011). Together these observations indicate that pruriceptive STT neurons are positioned within a complex and plastic circuitry that could provide a locus for pharmacological control of pruritus.

GRANTS

This work was funded by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants NS-047399 and NS-059199.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.D., D.A.S., and G.J.G. conception and design of research; S.D., X.Z., S.G.K., H.R.M., C.N.H., D.A.S., and G.J.G. performed experiments; S.D. analyzed data; S.D. and G.J.G. interpreted results of experiments; S.D. prepared figures; S.D. drafted manuscript; S.D., S.G.K., H.R.M., C.N.H., D.A.S., and G.J.G. edited and revised manuscript; S.D., X.Z., S.G.K., H.R.M., C.N.H., D.A.S., and G.J.G. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Hai Truong for his excellent surgical and technical assistance.

Present address of S. Davidson: Pain Center and Department of Anesthesiology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO 63110.

REFERENCES

- Akiyama T, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Excitation of mouse superficial dorsal horn neurons by histamine and/or PAR-2 agonist: potential role in itch. J Neurophysiol 102: 2176–2183, 2009a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Merrill AW, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Activation of superficial dorsal horn neurons in the mouse by a PAR-2 agonist and 5-HT: potential role in itch. J Neurosci 29: 6691–6699, 2009b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Facial injections of pruritogens and algogens excite partly overlapping populations of primary and second-order trigeminal neurons in mice. J Neurophysiol 104: 2442–2450, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Carstens MI, Carstens E. Transmitters and pathways mediating inhibition of spinal itch-signaling neurons by scratching and other counterstimuli. PLoS One 6: e22665, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrew D, Craig AD. Spinothalamic lamina I neurons selectively sensitive to histamine: a central neural pathway for itch. Nat Neurosci 4: 72–77, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickford RG. Experiments relating to the itch sensation, its peripheral mechanism and central pathways. Clin Sci 3: 377–386, 1938 [Google Scholar]

- Burstein R, Dado RJ, Cliffer KD, Giesler GJ., Jr Physiological characterization of spinohypothalamic tract neurons in the lumbar enlargement of rats. J Neurophysiol 66: 261–284, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstens EE, Carstens MI, Simons CT, Jinks SL. Dorsal horn neurons expressing NK-1 receptors mediate scratching in rats. Neuroreport 21: 303–308, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S, Giesler GJ., Jr The multiple pathways for itch and their interactions with pain. Trends Neurosci 33: 550–558, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Khasabov SG, Simone DA, Giesler GJ., Jr Relief of itch by scratching: state-dependent inhibition of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. Nat Neurosci 12: 544–546, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Khasabov SG, Simone DA, Giesler GJ., Jr Termination zones of functionally characterized spinothalamic tract neurons within the primate posterior thalamus. J Neurophysiol 100: 2026–2037, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson S, Zhang X, Yoon CH, Khasabov SG, Simone DA, Giesler GJ., Jr The itch-producing agents histamine and cowhage activate separate populations of primate spinothalamic tract neurons. J Neurosci 27: 10007–10014, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drzezga A, Darsow U, Treede RD, Siebner H, Frisch M, Munz F, Weilke F, Ring J, Schwaiger M, Bartenstein P. Central activation by histamine-induced itch: analogies to pain processing: a correlational analysis of O-15 H2O positron emission tomography studies. Pain 92: 295–305, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SK, Mancino V, Simon MI. Phospholipase C-beta mediates the scratching response activated by the histamine H1 receptor on C-fiber nociceptive neurons. Neuron 52: 691–703, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker HO, Forster C, Kirchhoff C. Discharge patterns of human C-fibers induced by itching and burning stimuli. J Neurophysiol 66: 307–315, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herde L, Forster C, Strupf M, Handwerker HO. Itch induced by a novel method leads to limbic deactivations—a function MRI study. J Neurophysiol 98: 2347–2356, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh JC, Hagermark O, Stahle-Backdahl M, Ericson K, Eriksson L, Stone-Elander S, Ingvar M. Urge to scratch represented in the human cerebral cortex during itch. J Neurophysiol 72: 3004–3008, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman OR, Wolkin J. Anterior cordotomy: further observations on the physiologic results and optimum manner of performance. Arch Neurol Psychiatry 50: 129–148, 1943 [Google Scholar]

- Ikoma A, Handwerker H, Miyachi Y, Schmelz M. Electrically evoked itch in humans. Pain 113: 148–154, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikoma A, Steinhoff M, Stander S, Yosipovitch G, Schmelz M. The neurobiology of itch. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 535–547, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamachi N, Park GH, Lee H, Anderson DJ, Simon MI, Basbaum AI, Han SK. TRPV1-expressing primary afferents generate behavioral responses to pruritogens via multiple mechanisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 11330–11335, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanek LM, Meyer RA, Hartke T, Hobelmann JG, Maine DN, LaMotte RH, Ringkamp M. Psychophysical and physiological evidence for parallel afferent pathways mediating the sensation of itch. J Neurosci 27: 7490–7497, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanek LM, Meyer RA, Friedman RM, Greenquist KW, Shim B, Borzan J, Hartke T, LaMotte RH, Ringkamp M. A role for polymodal C-fiber afferents in nonhistaminergic itch. J Neurosci 28: 7659–7669, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. The Thalamus (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- Kosteletzky F, Namer B, Forster C, Handwerker HO. Impact of scratching on itch and sympathetic reflexes induced by cowhage (Mucuna pruriens) and histamine. Acta Derm Venereol 89: 271–277, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMotte RH, Shimada SG, Green BG, Zelterman D. Pruritic and nociceptive sensations and dysesthesias from a spicule of cowhage. J Neurophysiol 101: 1430–1443, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langerstrom MC, Rogoz K, Abrahamsen B, Persson E, Reinius B, Nordenankar K, Olund C, Smith C, Mendez JA, Chen ZF, Wood JN, Wallen-Mackenzie A, Kullander K. VGLUT2-dependent sensory neurons in the TRPV1 population regulate pain and itch. Neuron 68: 529–542, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leknes SG, Bantick S, Willis CM, Wilkinson JD, Wise RG, Tracey I. Itch and motivation to scratch: an investigation of the central and peripheral correlates of allergen- and histamine-induced itch in humans. J Neurophysiol 97: 415–422, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipski J. Antidromic activation of neurons as an analytic tool in the study of the central nervous system. J Neurosci Methods 4: 1–32, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Weng HJ, Patel KN, Tang Z, Bai H, Steinhoff M, Dong X. The distinct roles of two GPCRs, MrgprC11 and PAR2, in itch and hyperalgesia. Sci Signal 4: ra45, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Tang Z, Surdenikova L, Kim S, Patel KN, Kim A, Ru F, Guan Y, Weng HJ, Geng Y, Undem BJ, Kollarik M, Chen ZF, Anderson DF, Dong X. Sensory neuron-specific GPCR Mrgprs are itch receptors mediating chloroquine-induced pruritus. Cell 139: 1353–1365, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Abdel Samad O, Zhang L, Duan B, Tong Q, Lopes C, Ji RR, Lowell BB, Ma Q. VGLUT2-dependent glutamate release from nociceptors is required to sense pain and suppress itch. Neuron 68: 543–556, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikula S, Trotts I, Stone JM, Jones EG. Internet-enabled high-resolution brain mapping and virtual microscopy. Neuroimage 35: 9–15, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki H, Tashiro M, Kano M, Sakurada Y, Itoh M, Yanai K. Imaging of central itch modulation in the human brain using positron emission tomography. Pain 105: 339–346, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochizuki H, Sadato N, Saito DN, Toyoda H, Tashiro M, Okamura N, Yanai K. Neural correlates of perceptual difference between itching and pain: a human fMRI study. Neuroimage 36: 706–717, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namer B, Carr R, Johanek LM, Schmelz M, Handwerker HO, Ringkamp M. Separate peripheral pathways for pruritus in man. J Neurophysiol 100: 2062–2069, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papoiu AD, Coghill RC, Kraft RA, Wang H, Yosipovitch G. A tale of two itches: common features and notable differences in brain activation evoked by cowhage and histamine induced itch. Neuroimage 59: 3611–3623, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel S, Ohara S, Dougherty PM, Gracely RH, Lenz FA. Psychophysical elements of place and modality specificity in the thalamic somatic sensory nucleus (ventral caudal, vc) of awake humans. J Neurophysiol 96: 646–659, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranck JB., Jr Which elements are excited in electrical stimulation of mammalian central nervous system: a review. Brain Res 98: 417–440, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VB, Iuga AO, Shimada SG, LaMotte RH, Lerner EA. Cowhage-evoked itch is mediated by a novel cysteine protease: a ligand of protease-activated receptors. J Neurosci 28: 4331–4335, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy VB, Shimada SG, Sikand P, LaMotte RH, Lerner EA. Cathepsin S elicits itch and signals via protease-activated receptors. J Invest Dermatol 130: 1468–1470, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringkamp M, Schepers RJ, Shimada SG, Johanek LM, Hartke TV, Borzan J, LaMotte RH, Meyer RA. A role for nociceptive, myelinated nerve fibers in itch sensation. J Neurosci 31: 14841–14849, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross SE, Mardinly AR, McCord AE, Zurawski J, Cohen S, Hu L, Mok SI, Shah A, Savner EM, Tolias C, Corfas R, Chen S, Inquimbert P, Xu Y, McInnes RR, Rice FL, Corfas G, Ma Q, Woolf CJ, Greenberg ME. Loss of inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal spinal cord and elevated itch in Bhlhb5 mutant mice. Neuron 65: 886–898, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz M, Schmidt R, Bickel A, Handwerker HO, Torebjork HE. Specific C-receptors for itch in human skin. J Neurosci 17: 8003–8008, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz M, Michael K, Weidner C, Schmidt R, Torebjork HE, Handwerker HO. Which nerve fibers mediate the axon reflex flare in human skin? Neuroreport 11: 645–648, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelz M, Schmidt R, Weidner C, Hilliges M, Torebjork HE, Handwerker HO. Chemical response pattern of different classes of C-nociceptors to pruritogens and algogens. J Neurophysiol 89: 2441–2448, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro PE, Braun CW. Unilateral pruritus after a stroke. Arch Dermatol 123: 1527–1530, 1987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim WS, Tak MH, Lee MH, Kim M, Kim M, Koo JY, Lee CH, Kim M, Oh U. TRPV1 mediates histamine-induced itching via the activation of phospholipase A2 and 12-lipoxygenase. J Neurosci 27: 2331–2337, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada SG, Shimada KA, Collins JG. Scratching behavior in mice induced by the proteinase-activated receptor-2 agonist, SLIGRL-NH2. Eur J Pharmacol 530: 281–283, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikand P, Shimada SG, Green BG, LaMotte RH. Similar itch and nociceptive sensations evoked by punctuate cutaneous application of capsaicin, histamine and cowhage. Pain 144: 66–75, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikand P, Dong X, LaMotte RH. BAM8–22 peptide produces itch and nociceptive sensations in humans independent of histamine release. J Neurosci 31: 7563–7567, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone DA, Alreja M, LaMotte RH. Psychophysical studies of the itch sensation and itchy skin (“alloknesis”) produced by intracutaneous injection of histamine. Somatosens Mot Res 8: 271–279, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone DA, Zhang X, Li J, Zhang JM, Honda CN, LaMotte RH, Giesler GJ., Jr Comparison of responses of primate spinothalamic neurons to pruritic and algogenic stimuli. J Neurophysiol 91: 213–222, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YG, Chen ZF. A gastrin-releasing peptide receptor mediates the itch sensation in the spinal cord. Nature 448: 700–703, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun YG, Zhao ZQ, Meng XL, Yin J, Liu XY, Chen ZF. Cellular basis of itch sensation. Science 325: 1531–1534, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurmond RL, Gelfand EW, Dunford PJ. The role of histamine H1 and H4 receptors in allergic inflammation: the search for new antihistamines. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7: 41–53, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckett RP. Itch evoked by electrical stimulation of the skin. J Invest Dermatol 79: 368–373, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valet M, Pfab F, Sprenger T, Woller A, Zimmer C, Behrendt H, Ring J, Darsow U, Tolle TR. Cerebral processing of histamine-induced itch using short-term alternating temperature modulation—an FMRI study. J Invest Dermatol 128: 426–433, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson SR, Gerhold KA, Bilfolck-Fisher A, Liu Q, Patel KN, Dong X, Bautista DM. TRPA1 is required for histamine-independent, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptor-mediated itch. Nat Neurosci 14: 595–602, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yosipovitch G, Greaves MW, Fleischer AB, Jr, McGlone F. Itch: Basic Mechanisms and Therapy. New York: Dekker, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Wenk HN, Honda CN, Giesler GJ., Jr Physiological studies of spinohypothalamic tract neurons in the lumbar enlargement of monkeys. J Neurophysiol 82: 1054–1058, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Davidson S, Giesler GJ., Jr Thermally identified subgroups of marginal zone neurons project to distinct regions of the ventral posterior lateral nucleus in rats. J Neurosci 26: 5215–5223, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]