Abstract

While Mdm2 is an important negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor, it also possesses p53-independent functions in cellular differentiation processes. Mdm2 expression is alternatively regulated by two P1 and P2 promoters. In this study we show that the P2-intiated transcription of Mdm2 gene is activated by 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 in MC3T3 cells. By using P1 and P2-specific reporters, we demonstrate that only the P2-promoter responds to vitamin D treatment. We have further identified a potential vitamin D receptor responsive element proximal to the two p53 response elements within the Mdm2 P2 promoter. Using cell lines that are p53-temperature sensitive and p53-null, we show requirement of p53 for VDR-mediated up regulation of Mdm2 expression. Our results indicate that 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3 and its receptor have a role in the regulation of P2-initiated Mdm2 gene expression in a p53-dependent way.

Keywords: VDR, Mdm2, p53, osteoblast differentiation, gene regulation

The murine double minute (Mdm2) gene was originally identified as being gene-amplified on double-minute chromosomes in transformed mouse fibroblast [1]. Mdm2 is a p53 inducible gene and encodes a type E3 ubiquitin ligase responsible for the degradation of p53 in the 26S proteosome [2]. A well established role for MDM2 is as a key negative regulator of p53 activity: p53 binds to the p53 responsive elements (p53REs) in the secondary promoter of the Mdm2 gene and activates MDM2 expression, while the subsequent increase of MDM2 protein results in its binding to p53 at the N-terminal 1–52 residues and leads to p53 degradation [3]. However, MDM2 also possesses numerous p53-independent activities, and is also known to interact with a number of other proteins (Numb, RB, p300, insulin like growth factor receptor, estrogen receptor, androgen receptor, etc.) involved in different cellular activities such as cell fate determination, differentiation and signaling [4, 5, 6, 7]. In the case of bone, it has been reported that targeted disruption of Mdm2 in this tissue causes skeletal abnormalities, osteopenia and osteoporosis [5].

Transcription of the Mdm2 gene is believed to be controlled by two distinct promoters (referred to as P1 and P2) [8, 9]. The P1 promoter, which is located at the upstream of the first exon, is responsible for the basal expression of Mdm2. The P2 promoter is situated in the first intron and is responsible for inducible expression. The two transcripts initiated from the P1 and P2 promoter encode identical full-length Mdm2 proteins by using the same translation start codon which is located in exon 2, while there are some differences in the 5’-untranslated regions (UTR) of these transcripts. A number of transcription factor binding sites have been identified in the P2 promoter region, including the two well-established p53RE sites [8,9], AP-1/ETS [10], Smad2/3 [11], and an Sp1 site within a GC box cluster [12]. Recently, it has been reported that a tissue-specific RXR can bind to its recognition site within the P2 promoter and activate expression of the Mdm2 gene in retinal cone cells [13]. Vitamin D is an important bone anabolic agent and several bone specific genes are directly regulated by this hormone. 1, 25 dihydroxy vitamin D3, the active form of Vitamin D exerts its action through its Vitamin D receptor (VDR) a ligand dependent transcription factor, belonging to the nuclear receptor family of transcription factors. Vitamin D mediates its action through a homodimer of VDR or as a heterodimer with Retinoic acid receptor in the regulation of bone specific genes.

Our work revolves around understanding the role of tumor suppressor gene p53 in osteoblast differentiation. We believe that Mdm2 under some conditions synergizes with p53 in the regulation of bone specific gene expression. In our previous study we have shown that MDM2 aids in the expression of osteocalcin, a bone-specific gene, during osteoblastic differentiation [14]. In this study we conducted in vitro and in vivo analyses to further investigate the regulation of the Mdm2 gene expression in osteoblast cells. We observed that Mdm2 expression could be upregulated by vitamin D3 and further identified a vitamin D receptor (VDR) responsive element in the P2 promoter of the Mdm2 gene.

Materials and methods

Cell Lines, Plasmids and Cell Culture

The mouse osteoblast cell line MC3T3 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) and rat osteosarcoma cell line ROS17/2.8 (kindly provided by Dr. Rodan, Merck Research Laboratory, West Point, PA) were used for these studies. A cell line stably expressing a temperature sensitive p53 plasmid was created in a p53 null osteosarcoma cell line [15]. The p53-null cell lines were also obtained from calvaria of p53 null mice as described earlier [16]. The two luciferase reporter plasmids, P1-Luc (containing Mdm2 P1 promoter) and P2-Luc (containing Mdm2 P2 promoter), were provided by Dr. Wu (University of California School of Medicine, Las Angeles, CA) [17]. The p53 expression vectors were a kind gift from Dr. Oren (Weisman Institute, Israel). Cell lines were grown in DMEM/F-12 with 10% fetal bovine serum in a modified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Transient Transfections and Reporter Assays

The cell lines were transfected with P2-Luc or other expression vectors using Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Luciferase activity was measured using equal amounts of cell lysates prepared from the transfected cells. All measurements were carried out on triplicate samples and experiments were repeated at least thrice.

Semi-quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNAs were isolated from MC3T3 cells using TRI reagent (Sigma Chemical Company, St Louis, MI). The primers for P1-initiated and P2-initiated Mdm2 transcripts were listed as follow: P1-Mdm2-F (5’-CTCGTCGCTCGAGCTCTGGA-3’), P1-Mdm2-R (5’-AGGTGCTTGCAGCACCCTCG-3’), and P2-Mdm2-F (5’-CTGGGGGACCCTCTCGGATC-3’), P2-Mdm2-R (5’-TGTGCTGCTGCTTCTCGTCA-3’). Reverse transcription-PCR was carried out using Onestep RT-PCR kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as follows: 50°C for 30 min, 95°C for 10 min, 45 cycles X 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1min, followed by the dissociation stage. PCR products were run on 2% agarose gel and semi-quantification of gene expression was determined by relative pixel densitometry using UNSCAN-IT (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT) for Mdm2 after normalization to β-Actin.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP assay was conducted to investigate the occupation of VDR to the P2 promoter of the Mdm2 gene in ROS17/2.8 cells by using an EZ-ChIP™ Assay Kit (Upstate, Temecula, CA) as described previously [18]. Mouse antibody N-20 against VDR (Santa Cruz Biotech, CA) was used in ChIP assays. The PCR primers used to detect target sequences were 5’-AGGGAAGAGCGGGGGTCTC-3’ (forward) and 5’-ACCAGGCACCTGTCACCTCCT-3’ (reverse) which span from −436 to −450 bp position within the P2 promoter region of the Mdm2 gene and generate a 101-bp fragment in PCR amplification.

Western Blot Assay

Protein lysates were prepared using MPER reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL). A Bradford assay was performed to determine protein concentration. 25–50 µg of the protein was run out on an SDS page gel, transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane, and blocked in 5% milk solution. Primary antibodies used in this study were mouse monoclonal p53 (Pab240) IgG (Santa Cruz Biotech, CA), mouse monoclonal Mdm2 (SMP14) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech, CA), rabbit VDR (N-20) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotech), and rabbit β-Actin antibody (Imgenex, San Diego, CA). The secondary antibodies used in Western blot were ImmunoPure Antibodoies (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) against rabbit and mouse IgGs, respectively. The blot was developed using SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate Kit (Thermo Scientific). Relative pixel densitometry was conducted using UNSCAN-IT for p53, MDM2 and VDR protein after normalization to β-Actin.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using software GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). The values given are mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analysis between two samples was performed using Student's t-test. In all cases, P < 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Mdm2 expression is upregulated by 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 in MC3T3 cells

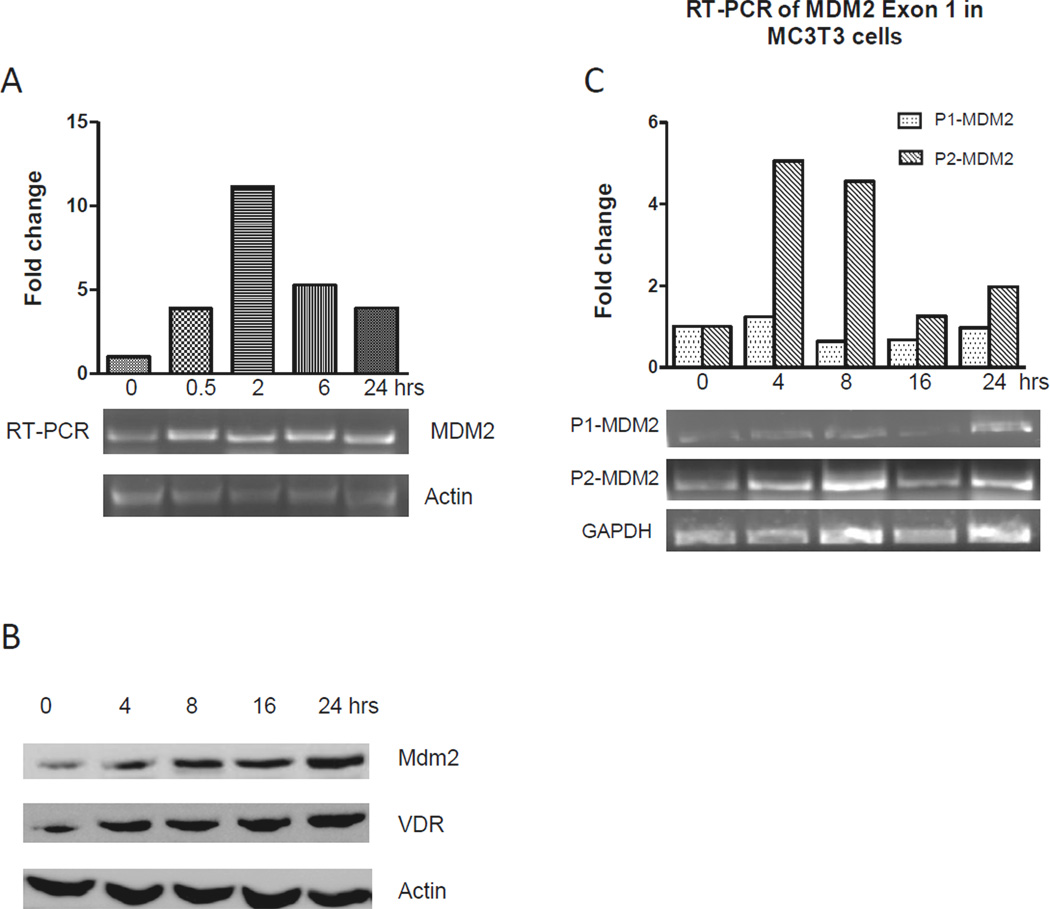

To investigate the effect of vitamin D3 on the Mdm2 gene expression, MC3T3 cells were treated with 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 at a final concentration of 20 nM and Mdm2 transcripts were measured after different periods (0, 0.5, 2, 6, and 24 hrs) by using semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1A, vitamin D3 treatment displayed a positive effect on the Mdm2 expression. The level of Mdm2 mRNA peaked at 2 hrs with an 11-fold increase compared to the control. Western Blot further revealed an increase in Mdm2 protein after vitamin D3 treatment (Fig 1B, top panel). Vitamin D receptor levels were also measured during the same period of time and showed responsiveness to vitamin D treatment as expected. (Figure 1B-bottom panel).

Fig. 1. Mdm2 expression is upregulated by vitamin D3.

(A) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR was performed on mRNA from MC3T3 cells in response to periodic treatment of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 (20 nM). Primers specific for all Mdm2 mRNA transcripts were used, and β-Actin was used as an endogenous control. Fold changes of Mdm2 expression are shown after normalization to β-Actin or GAPDH. (B) Western blot assay for Mdm2 and VDR protein expression with β-Actin as a control. Changes in relative protein levels after treatment with 20nM Vitamin D3 are indicated. (C) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR for the promoter P1 and P2 initiated Mdm2 mRNA transcription in MC3T3 cells subjected to vitamin D3 treatment. Fold changes of P1 and P2 initiated Mdm2 transcripts are shown after normalization to GAPDH.

Vitamin D3 mediates upregulation of Mdm2 expression through the Mdm2 P2 promoter

The Mdm2 gene has two alternative promoters to initiate two different full length isoforms of mRNA transcripts. To further investigate the effect of vitamin D3 on the Mdm2 expression, we detected levels of the two Mdm2 mRNA transcript isoforms generated by P1 and P2 promoter in MC3T3 cells after different periods of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 treatment. Two pairs of primers specific to the P1-initiated and the P2-initiated Mdm2 mRNA transcripts were used in semi-quantitative RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 1C, the P2-initiated transcript levels were increased significantly after treatment of vitamin D3, with the highest level of about 5.6-fold increasing at the 4-hr compared to the control. However, changes of the levels of P1-initiated Mdm2 transcripts were not observed during the vitamin D3 treatment (Fig. 1C).

A potential VDR responsive element is located in the Mdm2 P2 promoter

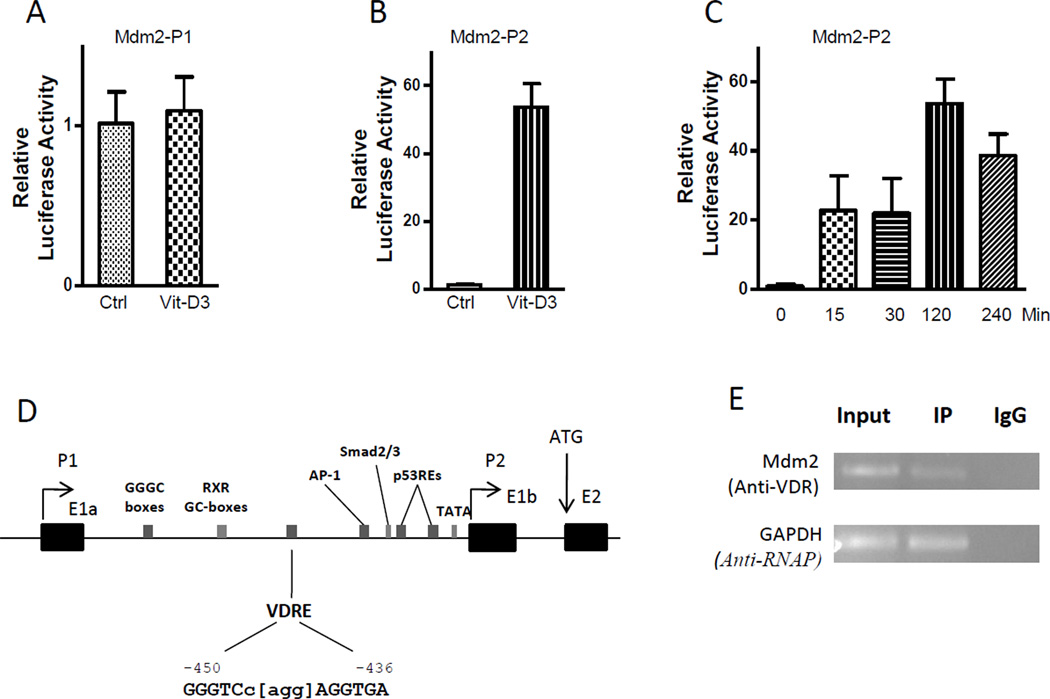

To further investigate the effect of vitamin D3 on the Mdm2 P1 and P2 promoter activity, we introduced P1 and P2 reporter plasmids into MC3T3 cells, and measured the promoter activation 2 hrs after 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 treatment. As shown in Fig. 2, no change of P1 promoter activity was observed after vitamin D3 treatment (Fig. 2A), but the P2 promoter displayed about 56-fold increased activity after vitamin D3 treatment compared to the control (Fig. 2B). We further detected a time dependent activation of the P2 promoter activity when measured after different intervals (0, 15, 30, 120, and 240 min). We observed that the P2 promoter activity was increased 15 mins after treatment of vitamin D3, and the maximal activity was seen at 2 hrs (Fig. 2C). It is well known that 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 can bind to the vitamin D receptor (VDR) to activate its targeted genes through its binding to vitamin D response element (VDRE) within the promoter region of targeted genes. Since our observations showed an early and robust increase in both P2-initiated Mdm2 transcription and P2 promoter activity by 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 we wanted to determine if this is a direct effect possibly mediated through a putative VDRE site within the P2 promoter of the Mdm2 gene.

Fig. 2. The identification of a VDR response element within the Mdm2 P2 promoter.

(A) to (C) The P1-Luc and P2-Luc plasmids were transiently transfected into MC3T3 cells with or without 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 (20 nM) treatment. Luciferase assays were done 2 hrs after transfection (A and B) or at different time points (C). The data are representative of 3–4 independent experiments. P values were determined by Student’s t-test. **, P < 0.05. Vit-D3, 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 treatment; Ctrl, the control without 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 treatment. (D) The P2 promoter region of the Mdm2 gene. Arrows, alternate transcription start sites (P1 and P2) and the translation start site (ATG); Black boxes, the alternate first exons (E1a and E1b) and the second exon (E2); Gray boxes, the predicted VDRE site and some known transcription factor binding sites. The nucleotide position is indicated based on A of the first codon (ATG) as +1 bp. (E) ChIP assay. Mouse MC3T3 cells were cross-linked, sonicated and then immunoprecipitated using an anti-VDR or anti-RNA polymerase antibodies. PCR was performed using specific primers for the predicted VDRE site in the Mdm2 P2 promoter and for the GAPDH promoter region as a control. Input, sonicated and precleared supernatant; IP, immunoprecipitated samples with anti-VDR or anti-RNA polymerase antibodies; IgG, negative controls treated with normal mouse IgG antibody.

We then searched for a consensus VDR binding sequence in the P2 promoter region of the Mdm2 gene. We noticed a potential DR3-type VDRE site (GGGTCc[agg]AGGTGA) at the −450 to −436-bp position of the Mdm2 gene (Fig. 2D), which contains two 6-nt RGKTSA VDRE-consensus sequences and a 3-nt spacer with only one mismatched nucleotide.

To verify whether the predicted VDRE site in the Mdm2 P2 promoter is bound by VDR protein, we conducted a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay in mouse MC3T3 cells. We used VDR specific antibodies to immunoprecipitate DNA-protein complexes from the cross-linked extract of sonicated cells, and amplified the VDR-immunoprecipitated DNA using primers spanning the putative VDRE-binding site in the Mdm2 P2 promoter. Human and rat osteocalcin gene were used as a positive control for VDRE-binding in the ChIP assay. We observed the Mdm2 P2 fragment containing the putative DR3-type VDRE sequence could be specifically amplified in anti-VDR immunoprecipitated samples from MC3T3 cells, but not in the negative control sample prepared with an anti-IgG antibody. This result that both VDR and the predicted VDRE sequence could be detected in a VDR-immunoprecipitated chromatin-protein complex, suggested that VDR protein is able to occupy the amplified site within the Mdm2 P2 promoter, and the 15-bp sequence contained in this amplified site is a potential DR3-type vitamin D response element.

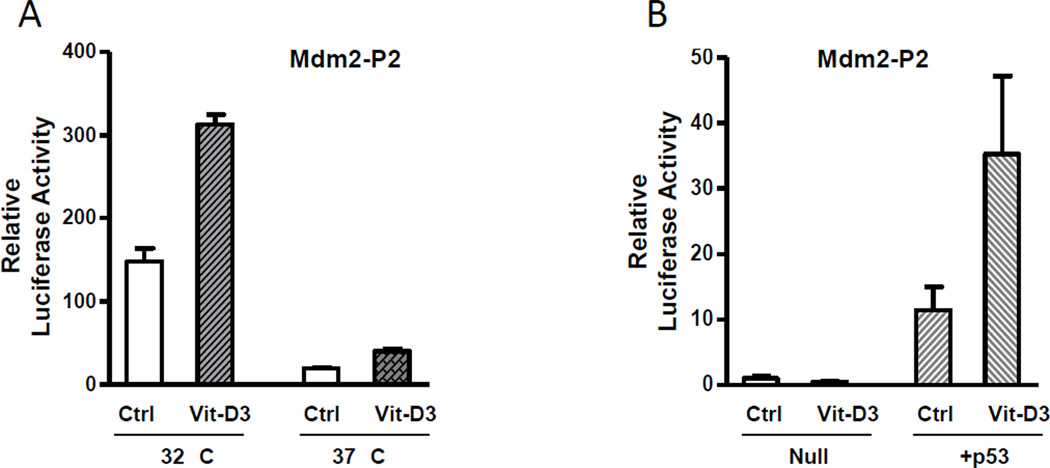

The presence of p53 is required for the VDR-mediated upregulation of Mdm2 expression

It has been well established that expression of the Mdm2 gene can be induced by p53 in response to a variety of physical conditions such as DNA damage and ribosomal stress via its cognate response element within the P2 promoter region. These two p53 response elements are located downstream of the predicted VDRE site within the P2 promoter region. In order to determine if p53 has a role in the VDR-mediated Mdm2 expression, we used two murine osteosarcoma cell lines with different p53 activities: one stably expressed a temperature-sensitive p53, and the other was null for p53. In the p53-temperature-sensitive cell line, transfections were conducted and the plates were incubated at 32°C (p53-wild type conformation) or 37°C (p53-mutant conformation) for 48 hours. 24 hours after transfection vitamin D3 was added where indicated. As shown in Fig. 3, luciferase activity was elevated in p53-temperature-sensitive cells when incubated at 32°C when p53 is in the wild type conformation and very low levels at 37°C, when p53 acquires the mutant conformation. Vitamin D treatment produced a significant increase of the Mdm2 P2 activity at 32°C and a small increase over control was also noted at 37°C (Fig. 3A). In p53-null cells, no change in Mdm2 P2 promoter activity was seen after the addition of vitamin D3. However, very high levels of Mdm2 P2 promoter activity were observed in p53-null cells after co-transfection with p53 expression plasmids, with a 13- and 36-fold increasing in the absence or presence of vitamin D3, respectively (Fig. 3B). Our observations in these experiments suggest that p53 protein might be essential to the vitamin D3-mediated activation of Mdm2 P2 promoter.

Fig. 3. P53 is required for the vitamin D3-mediated upregulation of the Mdm2 P2 promoter activity.

(A) The P2-Luc plasmid was transiently introduced into a p53-temperature sensitive cell line and incubated at 32°C and 37°C, and luciferase assays were done 2 hrs after the 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 (20 nM) treatment. (B) The P2-Luc and p53 expression plasmids were transfected and luciferase assays were done 2 hrs after treatment of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 (20 nM). All the results represent average +SE of triplicates of an experiment that was repeated thrice. P values were determined by Student’s t-test. **, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Mdm2 has been well characterized as a negative regulator of p53, while recent studies have shown a p53-independent role of Mdm2 in regulation of certain proteins that contribute to key aspects of cell proliferation, apoptosis, tumor invasion and metastasis. These targets of Mdm2 include Foxo3A [19, 20], XIAP [21], and E-cadherin [22]. Recently several studies have also demonstrated that Mdm2 is likely to have different biological effects, depending on the tissue and cell type that is examined [23, 24, 25]. Recently Mdm2 was shown to have a p53 independent role in adipocyte differentiation [26]. In our work we have shown p53 to have distinct transcription activating role in the regulation of a number of bone specific genes [15, 27]. In a recent study we show that p53 and Mdm2 have a synergistic role in the regulation of osteocalcin gene during osteoblastic differentiation [14]. In the present study we demonstrate that vitamin D3 may help mediate changes to Mdm2 gene expression which is dependent on the presence of wild type p53.

A number of transcription factor binding sites have been identified in the P2 promoter region, including the p53RE sites and the RXR site [13]. In this present study, we showed evidence for a potential VDRE site in the P2 promoter region of the Mdm2 gene, with experimental results indicating that Mdm2 expression is regulated by 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 treament. The actions of 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 are mediated by VDR phosphoprotein which binds the hormone with high affinity and regulates the expression of targeted genes via zinc finger-mediated DNA binding and protein-protein interactions with a basic model of the active receptor as a DNA-bound, 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3-liganded heterodimer of VDR and RXR. It is well established that 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D3 and its receptor VDR are crucial to the bone specific gene expression during osteoblast differentiation and bone remodeling [2, 4]. Different types of VDREs have been identified in the promoter regions of positively controlled genes expressed in bone, including osteocalcin [28], osteopontin [29], and vitamin D 24-OHase [30]. Multiple VDREs have recently been identified in the promoter region of the p21 gene, a transcriptional target of p53 [31]. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated the VDR binding sites are co-localized with p53 binding sites in the promoter of the p21 gene. In this present study, we identified a VDRE site, which is co-localized with the RXR binding site and the p53 response elements within the P2 promoter of the Mdm2 gene. It is reasonable to believe that the RXR binding site has a role in the VDR response, even though we do not have experimental evidence to support it. We have also observed that the presence of wildtype p53 is required for the vitamin D3-mediated regulation of Mdm2 expression, which suggests an interaction between p53REs and VDRE within the P2 promoter of the Mdm2 gene. This type of regulation requiring p53 to potentiate vitamin D action may be an important feature of differentiation and differentiated cells. P53 and its family members have also been implicated in the direct regulation of vitamin D receptor [32, 33]. Vitamin D by directly regulating Mdm2 expression may serve as part as a feed forward loop whereby p53 activity coordinates the ligand-dependent activation of Mdm2 expression during osteoblast differentiation.

Highlights.

Physiological levels of Vitamin D can induce an increase in Mdm2 expression.

Mdm2 and VDR levels are increased after vitamin D treatment

Mdm2-P2 initiated transcripts are increased with Vitamin D treatment.

A VDR binding site was detected on the Mdm2 promoter and was bound by VDR

Activation of Mdm2 by vitamin D requires the presence of wild type p53

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health grant R15 AR055362 to NC and funds from Midwestern University. We thank all individuals cited in the text for their kind gifts of reagents.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fakharzadeh SS, Trusko SP, George DL. Tumorigenic potential associated with enhanced expression of a gene that is amplified in a mouse tumor cell line. EMBO J. 1991;10:1565–1569. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07676.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodier F, Campisi J, Bhaumik D. Two faces of p53: aging and tumor suppression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:7475–7484. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen J, Marechal V, Levine AJ. Mapping of the p53 and mdm-2 interaction domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4107–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Z, Zhang R. p53-independent activities of MDM2 and their relevance to cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:9–20. doi: 10.2174/1568009053332618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lengner CJ, Steinman HA, Gagnon J, Smith TW, Henderson JE, Kream BE, Stein GS, Lian JB, Jones SN. Osteoblast differentiation and skeletal development are regulated by Mdm2-p53 signaling. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:909–921. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ganguli G, Wasylyk B. p53-independent functions of MDM2. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:1027–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinman HA, Burstein E, Lengner C, Gosselin J, Pihan G, Duckett CS, Jones SN. An alternative splice form of Mdm2 induces p53-independent cell growth and tumorigenesis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4877–4886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305966200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barak Y, Gottlieb E, Juven-Gershon T, Oren M. Regulation of mdm2 expression by p53: alternative promoters produce transcripts with nonidentical translation potential. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1739–1749. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.15.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zauberman A, Flusberg D, Haupt Y, Barak Y, Oren M. A functional p53-responsive intronic promoter is contained within the human mdm2 gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2584–2592. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ries S, Biederer C, Woods D, Shifman O, Shirasawa S, Sasazuki T, McMahon M, Oren M, McCormick F. Opposing effects of Ras on p53: transcriptional activation of mdm2 and induction of p19ARF. Cell. 2000;103:321–330. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00123-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Araki S, Eitel JA, Batuello CN, Bijangi-Vishehsaraei K, Xie XJ, Danielpour D, Pollok KE, Boothman DA, Mayo LD. TGF-beta1-induced expression of human Mdm2 correlates with late-stage metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:290–302. doi: 10.1172/JCI39194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bond GL, Hu W, Bond EE, Robins H, Lutzker SG, Arva NC, Bargonetti J, Bartel F, Taubert H, Wuerl P, Onel K, Yip L, Hwang SJ, Strong LC, Lozano G, Levine AJ. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the MDM2 promoter attenuates the p53 tumor suppressor pathway and accelerates tumor formation in humans. Cell. 2004;119:591–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu XL, Fang Y, Lee TC, Forrest D, Gregory-Evans C, Almeida D, Liu A, Jhanwar SC, Abramson DH, Cobrinik D. Retinoblastoma has properties of a cone precursor tumor and depends upon cone-specific MDM2 signaling. Cell. 2009;137:1018–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen H, Kolman K, Lanciloti N, Nerney M, Hays E, Robson C, Chandar N. p53 and MDM2 are involved in the regulation of osteocalcin gene expression. Exp Cell Res. 2012;318:867–876. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandar N, Swindle J, Szajkovics A, Kolman K. Relationship of bone morphogenetic protein expression during osteoblast differentiation to wild type p53. J Orthop Res. 2005;23:1345–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2005.04.010.1100230616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandar N, Donehower L, Lanciloti N. Reduction in p53 gene dosage diminishes differentiation capacity of osteoblasts. Anticancer Res. 2000;20:2553–2559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang CJ, Freeman DJ, Wu H. PTEN regulates Mdm2 expression through the P1 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29841–29848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401488200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen H, Hays E, Liboon J, Neely C, Kolman K, Chandar N. Osteocalcin gene expression is regulated by wild-type p53. Calcif Tissue Int. 2011;89:411–418. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9533-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang JY, Zong CS, Xia W, Yamaguchi H, Ding Q, Xie X, Lang JY, Lai CC, Chang CJ, Huang WC, Huang H, Kuo HP, Lee DF, Li LY, Lien HC, Cheng X, Chang KJ, Hsiao CD, Tsai FJ, Tsai CH, Sahin AA, Muller WJ, Mills GB, Yu D, Hortobagyi GN, Hung MC. ERK promotes tumorigenesis by inhibiting FOXO3a via MDM2-mediated degradation. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:138–148. doi: 10.1038/ncb1676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang W, Dolloff NG, El-Deiry WS. ERK and MDM2 prey on FOXO3a. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:125–126. doi: 10.1038/ncb0208-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gu L, Zhu N, Zhang H, Durden DL, Feng Y, Zhou M. Regulation of XIAP translation and induction by MDM2 following irradiation. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang JY, Zong CS, Xia W, Wei Y, Ali-Seyed M, Li Z, Broglio K, Berry DA, Hung MC. MDM2 promotes cell motility and invasiveness by regulating Ecadherin degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:7269–7282. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00172-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grier JD, Xiong S, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Parant JM, Lozano G. Tissue-specific differences of p53 inhibition by Mdm2 and Mdm4. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:192–198. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.192-198.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong S, Van Pelt CS, Elizondo-Fraire AC, Liu G, Lozano G. Synergistic roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 for p53 inhibition in central nervous system development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:3226–3231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508500103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maetens M, Doumont G, Clercq SD, Francoz S, Froment P, Bellefroid E, Klingmuller U, Lozano G, Marine JC. Distinct roles of Mdm2 and Mdm4 in red cell production. Blood. 2007;109:2630–2633. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hallenborg P, Feddersen S, Francoz S, Murano I, Sundekilde U, Petersen RK, Akimov V, Olson MV, Lozano G, Cinti S, Gjertsen BT, Madsen L, Marine JC, Blagoev B, Kristiansen K. Mdm2 controls CREB-dependent transactivation and initiation of adipocyte differentiation. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1381–1389. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bovenkerk S, Lanciloti N, Chandar N. Induction of p53 expression and function by estrogen in osteoblasts. Calcif Tissue Int. 2003;73:274–280. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-1041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demay MB, Gerardi JM, DeLuca HF, Kronenberg HM. DNA sequences in the rat osteocalcin gene that bind the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor and confer responsiveness to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:369–373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noda M, Vogel RL, Craig AM, Prahl J, DeLuca HF, Denhardt DT. Identification of a DNA sequence responsible for binding of the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhancement of mouse secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP-1 or osteopontin) gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:9995–9999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen KS, DeLuca HF. Cloning of the human 1 alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D-3 24-hydroxylase gene promoter and identification of two vitamin D-responsive elements. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1263:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00060-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saramaki A, Banwell CM, Campbell MJ, Carlberg C. Regulation of the human p21(waf1/cip1) gene promoter via multiple binding sites for p53 and the vitamin D3 receptor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:543–554. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kommagani R, Payal V, Kadakia MP. Differential regulation of vitamin D receptor (VDR) by the p53 Family: p73-dependent induction of VDR upon DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29847–29854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703641200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maruyama R, Aoki F, Toyota M, Sasaki Y, Akashi H, Mita H, Suzuki H, Akino K, Ohe-Toyota M, Maruyama Y, Tatsumi H, Imai K, Shinomura Y, Tokino T. Comparative genome analysis identifies the vitamin D receptor gene as a direct target of p53-mediated transcriptional activation. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4574–4583. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]