Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Emergency department (ED) use among seniors increased substantially in recent years. This study examined whether community and nursing home (NH) residents treated by a geriatrician were less likely to use the ED than patients treated by other physicians.

DESIGN

Retrospective cohort study using data from a national sample of seniors with a history of cardiovascular disease.

SETTING

Ambulatory care or NH.

PARTICIPANTS

Fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries ≥66 years diagnosed with ≥1 geriatric conditions from 2004 to 2007 and followed for up to 3 years.

MEASUREMENTS

ED use was measured in Medicare Inpatient and Outpatient claims; geriatric care was measured as geriatrician visits in ambulatory or NH settings coded in physician claims.

RESULTS

Multivariable analyses controlled for observed patient characteristics and unobserved patient characteristics that were constant during the study period. For community residents, receipt of ≥1 non-hospital geriatrician visits in a 6-month period was associated with an 11.3% reduction in ED use the following month (95% confidence interval (CI) = 7.5% to 15.0%, N=287,259). Compared to traditional primary care, reduction in ED use associated with primary care by geriatricians was similar to that associated with consultative care by geriatricians. Results for nursing home residents (N=66,551) were similar to those for community residents.

CONCLUSION

Geriatric care was associated with estimated annual decreases of 108 ED visits per 1,000 community residents and 133 ED visits per 1,000 NH residents. The results suggest that geriatric consultative care in collaboration with primary care providers may be as effective in reducing ED use as geriatric primary care. Increased provision of collaborative care could allow the existing supply of geriatricians to reach a larger number of patients.

Keywords: geriatric care, primary care, nursing home, emergency department

INTRODUCTION

Health care for older adults with chronic conditions is costly and often of suboptimal quality.1,2 The quality of health care for geriatric conditions such as dementia and urinary incontinence may be considerably poorer than for chronic conditions such as hypertension.3 Suboptimal outpatient care may result in excessive emergency and hospital health care use. For example, emergency department (ED) use among adults aged 65 to 74 increased 34% from 1993 to 2003.4 This trend is problematic because ED use is costly, stressful for frail seniors, and often leads to inappropriate medication use and hospitalization.4–6 Thus, reducing ED use is desirable from the perspectives of patients, providers, payers, and society.

Geriatricians’ training and experience may enable them to better address complex physical, cognitive, mental, and social issues faced by older adults. Geriatricians have expertise in managing geriatric syndromes, optimizing use of medications, and supporting patients and caregivers who make critical healthcare decisions.7 This expertise may allow them to manage acute and chronic illnesses in ways that reduce acute care episodes, including ED use.

The current evidence base for geriatric care is derived from clinical trials of interdisciplinary care delivered in controlled circumstances. Results from these trials suggest that comprehensive geriatric assessment delivered as part of multi-visit outpatient or in-home care reduces ED use; however, the same is not true for consultative care.8–10 Notably, these trials are of limited use in understanding the effect of care by geriatricians in real-world settings because they have excluded nursing home (NH) residents and are conducted using structured protocols in optimal academic settings. Results of five observational studies suggest that geriatric care may be associated with fewer primary care physician visits, reduced likelihood of inappropriate prescribing or hospitalization, shorter hospital length of stay, or lower health care costs.11–15 However, drawing conclusions from these studies is difficult because they: used varied definitions of geriatric care; had small sample sizes with limited generalizability; and failed to control for unobservable factors that may have affected the relationship between geriatric care and outcomes.

The study assesses the real-world association of care by geriatricians in non-hospital settings on ED use using longitudinal Medicare claims data from a large national sample of Medicare beneficiaries with a history of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and at least one geriatric condition. The primary study hypothesis was that receipt of geriatric care would be associated with reduced ED use, and this hypothesis was tested separately for community and long-term NH residents.

METHODS

Data and sample

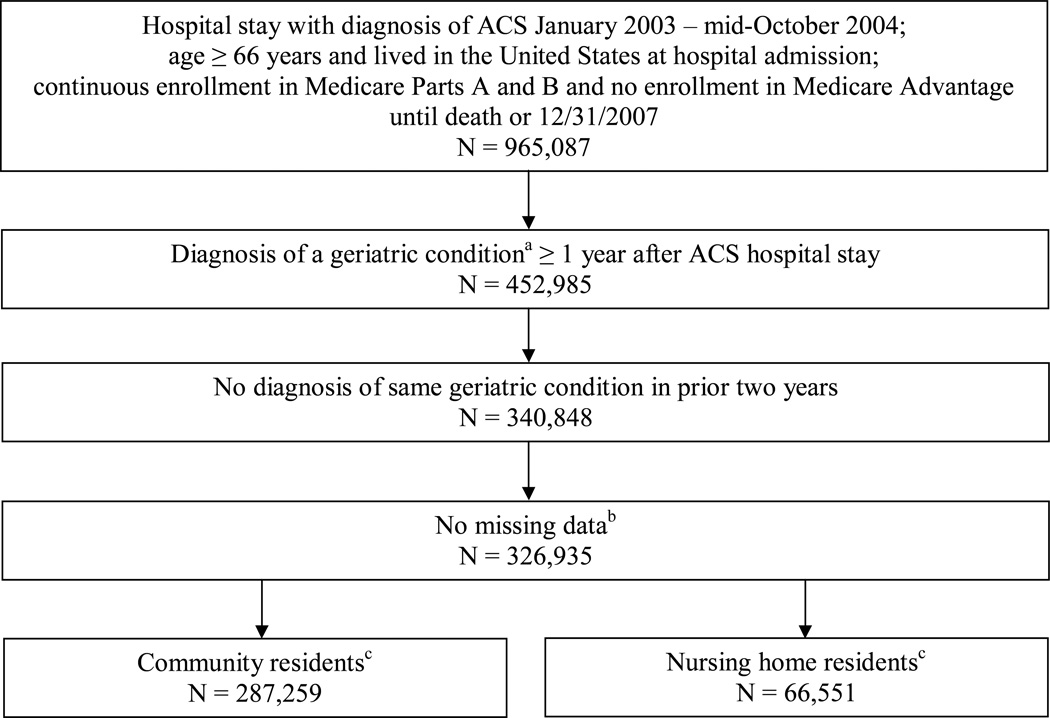

Subjects were drawn from a national sample of Medicare enrollees with a history of ACS and a subsequent diagnosis of at least one of sixteen geriatric conditions that have been used for inclusion in trials of comprehensive geriatric assessment or recognized as a characteristic of patients who are most likely benefit from geriatric care (Figure 1).16 The sample came from a nationally representative group of 965,087 fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries included in a study of cardiovascular disease.17 That group of nearly one million individuals included all Medicare beneficiaries who met the following criteria: (1) acute care hospital stay with a diagnosis of ACS (ICD-9-CM codes 410.xx, 411.1x, and 413.9x) from January 2003 through mid-October 2004; (2) age > 66 years and lived in the U.S.(excluding territories) at hospital admission; and (3) continuous enrollment in Medicare Parts A and B and no enrollment in Medicare Advantage until death or 12/31/2007.

Figure 1. Sample Selection.

ACS = acute coronary syndromes

aStroke (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes 430.xx–432.xx, 434.xx–437.1x, 437.3x–438.xx), dementia (290.0–290.43, 294.0–294.8, 331.0–331.2, 331.7, 797), depression (300.4, 301.12, 309.0, 309.1, 311), delirium (293.0x, 293.1x), pressure ulcer (707.0x, 707.2x–707.9x), fracture (800.xx--829.xx), dislocation (830.xx–839.xx), laceration (870.xx–879.xx, 880.xx–884.xx, 890.xx–894.xx), osteoporosis (733.0), syncope (780.2), hearing impairment (389.xx), vision impairment (369.xx), urinary incontinence (596.51–596.52, 596.54–596.59, 599.8x, 625.6x, 788.3, 788.30–788.34, 788.37–788.39), weight loss/failure to thrive (260–263.9, 783.21–783.22, 783.7x), or dehydration (276.5)

bMost patients with missing data had missing income data; their ZIP code did not match a ZIP code tabulation area in the 2000 Census

c26,875 patients were in both samples

From the original study sample, we identified patients diagnosed with a geriatric condition at least one year after the hospitalization for ACS who were not diagnosed with the same condition in the prior two years. These criteria created a buffer between measurement of geriatric care and use of cardiac care related to ACS and maximized the likelihood that the geriatric condition diagnosis represented the onset of the condition. Patients with cardiovascular disease may have poorer functional status and overall health status than the general population of seniors.18 Therefore, by including patients with ACS who were subsequently diagnosed with a geriatric condition, the study sample represents older patients with a higher likelihood of benefiting from geriatric care than the general Medicare population. In addition, the large sample provided sufficient power to conduct an analysis of geriatric care, which is relatively rare.

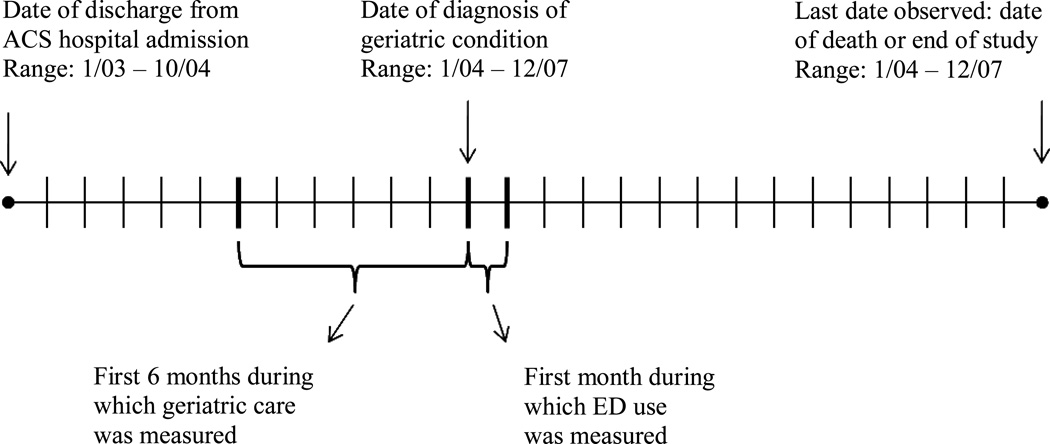

Data from Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR), Outpatient, Carrier, and Denominator files were available for 2002 through 2007. By combining these files for each patient, the dataset included data from inpatient care, outpatient care, physician visits in all settings, and demographic characteristics. Observations were constructed for 30-day periods (subsequently referred to as “months”) for each patient beginning with the date of diagnosis of the geriatric condition (Figure 2). A patient was in the community sample until death, end of study, or the first month he or she was identified as a long-term NH resident. A patient was in the NH sample from the first month he or she was identified as being a long-term NH resident until death or end of study. Patients were classified as NH residents if they had ≥3 consecutive months with ≥1 NH Carrier claim and no skilled nursing facility (SNF) claims for at least one of those months. Upon entering a long-stay hospital, a patient was permanently excluded from both samples because their patterns of health care use were substantially different from other patients.

Figure 2. Study Timeline.

ACS = acute coronary syndromes

ED = emergency department

Measures of geriatric care

Physician visits were identified by codes for evaluation and management services provided during office, home, and NH visits, or for consultations provided in one of those settings.19–20 (Visits with Berenson-Eggers Type of Service (BETOS) codes M1A, M1B, M4A, M4B, and M6 were included unless one of the following Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) codes was present: 99221–99239, 99251–99255, 99261–99263, 99271–99275, 99411–99412, 95115–95117, or G0175.) Each physician was identified by a Unique Provider Identification Number that started with a letter between A and M.20–21 Physicians (or their institutions on physicians’ behalf) initially self-designate specialty when applying to become Medicare providers. Specialty appears on each claim in the physician visit claims file; 38 refers to geriatric medicine.

Geriatricians, who usually initially specialize in family medicine or internal medicine, may have multiple specialties on claims in a single year (e.g., internal medicine on hospital claims and geriatric medicine on office claims). Because physicians for whom geriatric medicine is listed in any claim were likely to apply their knowledge and experience in the care of all older patients, each physician with ≥2 visits coded as geriatric medicine in one year was considered to be a geriatrician for all office, home and/or NH visits/consultations in that year. Most (79.3%) physicians with ≥2 visits coded as geriatric medicine in one year had all physician visits for the original sample of nearly one million Medicare beneficiaries coded as geriatric medicine in that year, suggesting that the majority were practicing geriatricians.

Physician visits were measured by specialty group. Three specialty groups were used: geriatricians, family and internal medicine (FM/IM) physicians, and other specialists. Visits to general practitioners, preventive medicine physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants were included with FM/IM physicians. Other specialists included physician specialties other than geriatrics or primary care.

Three measures of geriatric care during six month periods were used. Two measures indicated the dose of geriatric care: zero vs. ≥1 visits, and number of visits (zero vs. 1, 2, or ≥3 visits). The third measure indicated geriatric care as a share of all physician visits, because plurality of visits has been used as an indicator of the primary care physician in studies of pay for performance.20,22 The reference category was patients with zero geriatrician visits for whom FM/IM visits represented the largest share of physician visits (“FM/IM plurality”). Three groups were compared to FM/IM plurality: (1) patients for whom geriatrician visits represented the largest share of physician visits (“geriatrician plurality”); (2) patients who had ≥1 geriatrician visits but for whom geriatrician visits did not represent the largest share of physician visits (“geriatrician consultation”); and (3) patients who had zero geriatrician visits and for whom specialist visits represented the largest share of physician visits (“specialist plurality”). These definitions of physician plurality and consultation do not provide information about the type of care provided; instead, they indicate whether the specialty group was the predominant provider for the patient.

Outcome and control variables

The dichotomous outcome (whether the patient had any ED use in a month) was obtained from inpatient and outpatient claims.23 Control variables of age, gender, and race came from the Denominator (demographic) file. Comorbidities were measured in inpatient, outpatient, and physician visit claims data using the Elixhauser index and geriatric conditions used for sample selection.16, 24–25

Metropolitan status was obtained by linking patient ZIP code to Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes.26 ZIP code level data on median household income was included.27 Dual eligibility was measured by whether the patient had some or all of their Medicare costs paid by the state Medicaid program.28 Dichotomous month variables controlled for seasonal variation in ED use, and year variables captured annual trends in ED use that occurred during the study period.

Statistical analyses

To account for control variables that may influence the relationship between geriatric care and ED use, an ordinary least squares linear regression model was used to estimate the association between ED use in one month and geriatric care received during the previous six months. This approach ensured that geriatric care was measured prior to the period during which ED use was measured.

Preliminary analyses showed that unobserved patient characteristics were related to both ED use and use of geriatric care, which suggested that preliminary estimates of the association between ED use and use of geriatric care were affected by selection bias. In other words, compared to patients who did not use geriatric care, patients who used geriatric care may have been different in unobservable ways that affected ED use. We initially used a statistical method that accounts for this selection (i.e., instrumental variables analysis). However, because those results were implausibly large, final analyses minimized the effects of selection bias by controlling for patient-level unobserved characteristics that did not vary during the study period (i.e., fixed effects analysis). In addition, study results were interpreted conservatively as evidence of associations rather than causal relationships.

Three sets of sensitivity analyses were conducted: (1) effect of county-level geriatrician supply on the relationship between geriatric care and ED use; (2) use of 3- and 9-month measures of geriatric care rather than the 6-month measure; and (3) use of a less restrictive measure of long-term NH use (≥2 consecutive months with ≥1 NH claim and no restriction on SNF claims). In all three cases, results were similar to those from the primary analyses and therefore are not discussed further.

A more detailed description of methods and full regression results are available from the authors upon request. All analyses were performed using Stata 11.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). This study was approved by the Public Health-Nursing Institutional Review Board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Sample sizes were 287,259 community residents (5,277,762 patient-month observations) and 66,551 NH residents (1,005,122 observations); 26,875 individuals had observations in both groups. Following diagnosis of a geriatric condition, patients were observed for a median of 17 months in the community and 14 months in the NH. The majority of both groups were female, white, and ≥80 years old in the first month of observation. At baseline, community residents with ≥1 geriatrician visits had more geriatric conditions (1.5 versus 1.3) and comorbidities than those with zero visits (3.6 versus 3.2), while NH residents had no differences (1.3 geriatric conditions and 4.6 comorbidities for both users and non-users of geriatric care) (Table 1). These data suggest that geriatric care is selectively used by community residents based on poor health status, but selection based on poor health status does not occur among NH residents.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics in the First Month of Observation Based on Whether Patient Had Geriatric Care in Previous 6 Months

| Community, 0 Geriatrician Visits |

Community, ≥1 Geriatrician Visits |

NH, 0 Geriatrician Visits |

NH, ≥1 Geriatrician Visits |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observations | 284,088 | 3,171 | 64,074 | 2,477 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age | 80.4 | 82.6** | 84.1 | 84.6 |

| Male, % | 37.8 | 32.2** | 28.6 | 28.2 |

| Nonwhite, % | 10.2 | 13.9** | 11.5 | 14.2** |

| Dual eligible, % | 17.1 | 17.1 | 35.0 | 34.3 |

| ZIP median income | $42,664 | $46,296 | $43,826 | $48,148** |

| Metropolitan area | 68.4 | 88.1 | 72.4 | 90.4** |

| Geriatric conditions | ||||

| Total number of geriatric conditions | 1.3 | 1.5** | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Stroke | 20.4 | 19.6 | 33.3 | 30.8** |

| Dementia | 13.1 | 23.3** | 44.0 | 52.8** |

| Osteoporosis | 16.2 | 19.8** | 15.8 | 18.4** |

| Urinary tract infection | 7.1 | 10.3** | 7.7 | 9.2** |

| Depression | 11.5 | 16.5** | 16.1 | 20.1 |

| Dehydration | 15.2 | 14.5 | 14.3 | 14.2 |

| Hearing impairment | 5.5 | 6.1 | 3.9 | 3.9 |

| Syncope | 12.5 | 10.9** | 6.3 | 6.5 |

| Fracture | 12.8 | 10.9** | 16.6 | 13.6** |

| Pressure ulcer | 2.6 | 4.1** | 7.1 | 8.0 |

| Weight loss | 6.8 | 8.9** | 6.1 | 9.7** |

| Vision impairment | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Failure to thrive | 0.7 | 1.2** | 1.7 | 3.2** |

| Laceration | 3.5 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 4.3** |

| Delirium | 1.0 | 1.5** | 2.2 | 2.7 |

| Dislocation | 1.9 | 0.8** | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Total number of comorbidities | 3.2 | 3.6** | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Hypertension | 76.7 | 82.3** | 84.4 | 85.1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 34.1 | 42.2** | 60.2 | 60.8 |

| Diabetes | 34.4 | 34.2 | 42.9 | 41.5 |

| Anemia | 26.6 | 33.7** | 46.9 | 52.2** |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 26.7 | 26.0 | 36.8 | 32.9** |

| Peripheral vascular | 17.9 | 22.4** | 34.8 | 34.0 |

| Hypothyroidism | 17.9 | 21.1** | 24.9 | 26.4 |

| Valvular disease | 15.6 | 18.1** | 19.4 | 16.6** |

| Neurological | 7.3 | 10.1** | 18.5 | 19.7 |

| Diabetes with complications | 10.9 | 12.8** | 16.8 | 16.4 |

| Renal failure | 10.5 | 11.7* | 17.0 | 16.3 |

| Tumor | 10.6 | 10.2 | 9.2 | 8.0* |

| Electrolytes | 8.2 | 8.4 | 10.7 | 10.9 |

| Hypertension with complications | 9.0 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 7.7* |

| Psychoses | 2.2 | 3.4** | 9.2 | 9.3 |

Differences between patients with ≥1 geriatrician visits and patients with 0 geriatrician visits are statistically significant at p<0.05

Differences between patients with ≥1 geriatrician visits and patients with 0 geriatrician visits are statistically significant at p<0.01

Comorbidities with prevalence of less than 5%, month indicators, and time trend variables were included in the model but are not reported here.

NH = nursing home

Geriatric care was uncommon in both groups but more common among NH residents than community residents. NH residents had ≥1 geriatrician visits during 5.2% of their 6-month periods, compared to 1.4% for community residents (Table 2). In addition, NH residents who used geriatric care were more likely to have multiple geriatrician visits in a 6-month period than were community residents who used geriatric care. Geriatrician plurality and geriatrician consultation occurred approximately equally often in both groups. Community residents were much more likely to have specialist plurality than NH residents.

Table 2.

Use of Geriatric Care and Emergency Department Use

| Community | NH** | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-month observations | 5,277,762 | 1,005,122 |

| Geriatric care during previous 6 months | ||

| ≥1 geriatrician visits, % | 1.4 | 5.2 |

| Number of geriatrician visits, % | ||

| 0 visits | 98.6 | 94.8 |

| 1 visit | 0.5 | 1.2 |

| 2 visits | 0.3 | 0.9 |

| ≥3 visits | 0.6 | 3.1 |

| Physician use, % | ||

| Family medicine/internal medicine plurality | 68.2 | 84.8 |

| Geriatrician plurality | 0.7 | 2.5 |

| Geriatrician consultation | 0.7 | 2.7 |

| Specialist plurality | 30.4 | 10.0 |

| Dependent variable | ||

| Any emergency department use in 1 month, % | 8.0 | 9.6 |

The monthly rate of ED use was somewhat higher among NH residents than community residents (9.6% vs. 8.0%). The majority of NH residents (65.8%) and community residents (60.2%) had at least one ED visit during the time that patients were observed following diagnosis of a geriatric condition.

Association between geriatric care and ED use

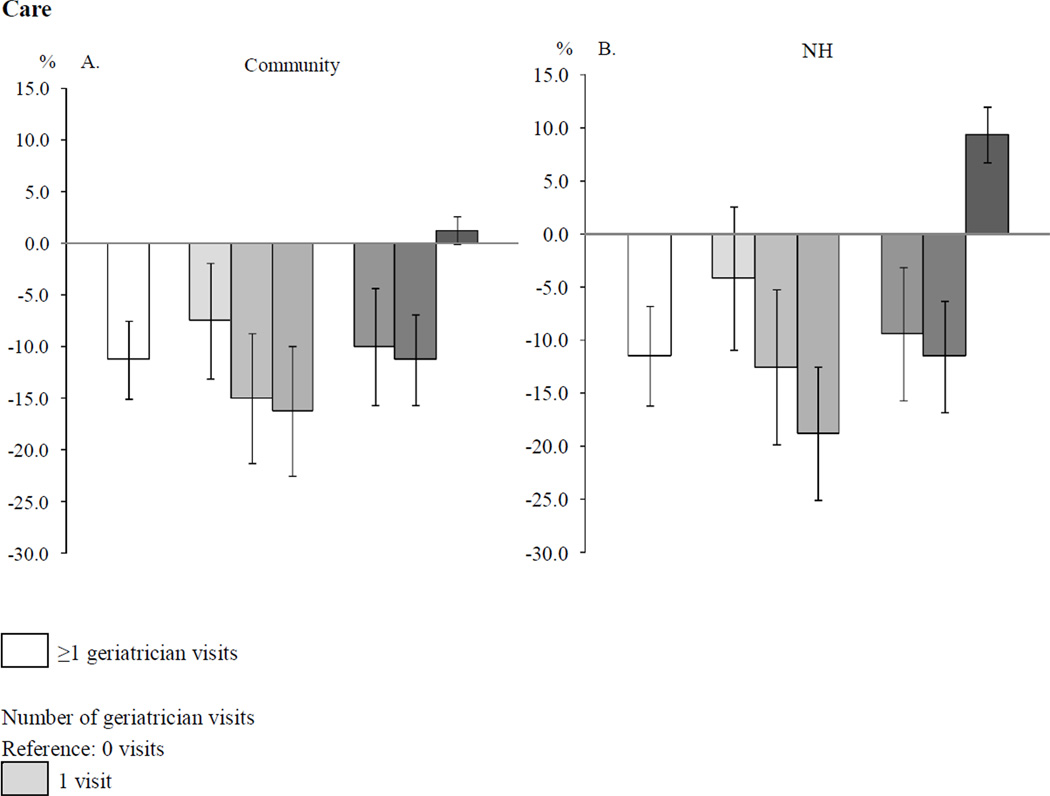

Most measures of geriatric care were associated with less ED use for community and NH residents. Although small in an absolute sense, estimated reductions in ED use were relatively large compared to average monthly rates of ED use. For community residents, ≥1 geriatrician visits was associated with an 11.3% decrease in the average monthly ED use for community residents (Figure 3). For NH residents, ≥1 geriatrician visits was associated with an 11.5% decrease from NH residents’ average monthly ED use. The largest reduction in the predicted probability of ED use was associated with ≥3 geriatrician visits (16.3% for community residents and 18.8% for NH residents). However, the estimated effect of ≥3 geriatrician visits was not significantly different from the estimated effect of 2 visits for either sample.

Figure 3. Percent Change in Predicted Probability of Emergency Department Use in One Month Associated with Geriatric Care.

NH = nursing home

Notes: 95% confidence intervals shown. Models control for demographic variables, geriatric conditions, comorbidities, month indicators, and time trends.

Percent change calculated as change in predicted probability of emergency department (ED) use (not reported) divided by the sample mean of ED use (Table 1) multiplied by 100. For example, for community residents, the reduction in ED use associated with ≥1 geriatrician visits was 0.9 percentage points; compared to the sample average of 8.0% for ED use for community residents, the result is an 11.3% decrease in ED use.

Patients who received geriatrician plurality or geriatrician consultation were less likely to have ED use than patients for whom FM/IM physicians accounted for the plurality of visits. For community residents, the reduction in ED use was 10.0% (with geriatrician plurality) and 11.3% (with geriatrician consultation). For NH residents, the reduction in ED use was 9.4% (with geriatrician plurality) and 11.5% (with geriatrician consultation). The reduction in ED use associated with geriatrician plurality was not significantly different from the reduction in ED use associated with geriatrician consultation in either sample.

For NH residents, use of specialty care for the plurality of visits was associated with an increase of 9.4% in the predicted probability of ED use in one month compared to NH residents in the FM/IM plurality reference group. ED use for community residents with specialist plurality was not significantly different from ED use with FM/IM plurality.

DISCUSSION

Randomized trials demonstrate benefits from interdisciplinary geriatric assessment; however, little is known about how geriatric care affects the health service use of Medicare patients in real-world settings. This study is the first to examine the association of geriatric care with ED use in a national sample of community and NH residents. Among Medicare patients with a history of ACS who were subsequently diagnosed with a geriatric condition, geriatric care was associated with reduced ED use by both community and NH residents. Estimated reductions (7.5%–18.8% reduction in likelihood of ED use in one month) were significant at the level of the individual patient and have broad public health implications in this population. These results suggest that for seniors like those in this study, having ≥1 geriatrician visits in a year is associated with estimated annual decreases of 108 ED visits/1,000 community residents and 133 ED visits/1,000 NH residents. Further, these results may underestimate the effect of geriatric care on ED use. The descriptive statistics show that community residents with ≥1 geriatrician visits were older and had more geriatric conditions than community residents with zero geriatrician visits. The finding that community residents who received geriatric care had poorer health and were less likely to use the ED than those who did not receive geriatric care is notable, because one would normally expect patients with poorer health to be more likely to have ED use.

Low geriatrician supply in the U.S. has long been a concern.29–30 In this study, geriatric care was relatively rare; only 2.7% of community and 8.4% of NH residents had ≥1 geriatrician visits during time they were observed (median of 17 months). An estimated 36,000 geriatricians will be needed to serve the growing population of older adults in 2030, but the projected supply of geriatricians in 2030 is only 7,750.2,31 One factor that likely reduces geriatrician supply is remuneration. Despite having completed fellowship training, geriatricians are typically paid less than FM/IM physicians.32–33 Geriatricians were included in the list of primary care providers eligible for a 10% incentive payment from Medicare for primary care services from 2011 to 2015 as part of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.34 A bill reintroduced in the Senate in 2011 would have amended the National Health Services Corps program to include geriatrics under primary health services, which would enable geriatricians to receive loan repayment in exchange for work in Health Professional Shortage Areas.35 However, the bill was not voted on by the committee to which it was assigned.

The effects of policy changes on geriatrician supply are unlikely to occur in the short-term (if at all). Therefore, the leading policy implication of this study may be to use the existing supply of geriatricians more efficiently. For example, reductions in monthly ED use associated with geriatrician consultation and geriatrician plurality were similar. This may suggest that consultative care or co-management may be as effective as primary care by geriatricians for this patient population. Notably, the similar reductions in ED use associated with geriatrician consultation and geriatrician plurality differ from results of randomized controlled trials of comprehensive geriatric assessment, which have found that only ongoing multi-visit geriatric care reduced ED use, not consultative care.8–10 This difference could be due in part to differences in patient populations or definitions of geriatrician consultation. For example, in 44% of the 6-month periods that community residents had geriatrician consultation, the plurality of visits was to specialists. In that case, the geriatrician may have been acting as the primary care physician even though the 6-month period was identified as geriatrician consultation.

Further studies using primary data collection or intervention designs could examine how geriatrician consultants can work collaboratively with FM/IM physicians to help reduce rates of ED use and improve other health outcomes.8,36 Among the list of payment and delivery reform models to be given priority by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is the use of geriatric assessments.37 If additional evidence suggests that geriatric consultation is effective in conjunction with primary care from FM/IM physicians, then the existing supply of geriatricians could reach a larger number of patients using collaborative care.

This study has several limitations. First, results cannot be generalized to patients without a history of ACS and a geriatric condition nor to those enrolled in Medicare managed care. Second, the claims data lacked a number of variables that would have been useful, including functional and cognitive status, social support, provider-level variables (e.g., nurse practitioner and physician assistant specialty), and quality of life. The mechanisms by which geriatric care may reduce ED use are unclear since such details are not in claims data. Third, because unobserved time-varying patient characteristics such as declining functional status may be associated with both ED use and geriatric care, study results were interpreted conservatively as evidence of associations rather than causal relationships. Finally, some FM/IM physicians have extensive experience caring for patients with geriatric conditions. Because physicians self-identify specialty when applying to become a Medicare provider, the measure of geriatric care used in this study does not require that a physician be certified in geriatric medicine.

This research extends current knowledge by examining the real-world association of geriatric care with ED use by elderly Medicare patients. The findings provide insights into effective models of care for elders with geriatric conditions, an issue that is critically important in light of the rapidly growing population of older adults and looming challenges to financial solvency for Medicare. Studies should continue to examine the models of geriatric care that have the greatest potential for improving the health of older adults and reducing unnecessary health care use and expenditures. Effective dissemination of geriatric care with avoidance of some ED use has potential benefits to all stakeholders – patients, families, providers, and payers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Frank A. Sloan for helpful comments.

This publication was made possible by Grant Numbers 2T32AG00027206A2 and 1R01AG025801 from the National Institute on Aging and 5T32HS00003222 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist provided by the authors and has determined that the authors have no financial or any other kind of personal conflicts with this paper.

Author Contributions: All authors participated in study design, analysis, and manuscript preparation, and all authors approved the final version. Dr. D’Arcy was primarily responsible for study design, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. Dr. Stearns acquired the data and provided extensive contributions to study design and analysis.

Sponsor’s Role: Neither the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality nor the National Institute on Aging had a role in the study design, methods, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2635–2645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa022615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morley JE, Paniagua MA, Flaherty JH, et al. The challenges to the continued health of geriatrics in the United States. In: Sterns HL, Bernard MA, editors. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics. Springer Pub Co; 2008. pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wenger NS, Solomon DH, Roth CP, et al. The quality of medical care provided to vulnerable community-dwelling older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:740–747. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-9-200311040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roberts DC, McKay MP, Shaffer A. Increasing rates of emergency department visits for elderly patients in the United States, 1993 to 2003. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:769–774. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caterino JM, Emond JA, Camargo CA., Jr Inappropriate medication administration to the acutely ill elderly: A nationwide emergency department study, 1992–2000. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1847–1855. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially avoidable hospitalizations of nursing home residents: Frequency, causes, and costs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:627–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Geriatrics Society. Geriatric medicine: A clinical imperative for an aging population, part I. Ann Long-Term Care. 2005;13:18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Counsell SR, Callahan CM, Clark DO, et al. Geriatric care management for low-income seniors. JAMA. 2007;298:2623. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCusker J, Verdon J. Do geriatric interventions reduce emergency department visits? A systematic review. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61:53–62. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Totten A, Carson S, Peterson K, et al. Evidence Review: Effect of Geriatricians on Outcomes of Inpatient and Outpatient Care. [Accessed August 30, 2012];Department of Veterans Affairs Evidence-based Synthesis Program. 2012 Jun; Available from http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/geriatricians.cfm. [PubMed]

- 11.Fenton JJ, Levine MD, Mahoney LD, et al. Bringing geriatricians to the front lines: Evaluation of a quality improvement intervention in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19:331–339. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.19.4.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hermush V, Daliot D, Weiss A, et al. The impact of geriatric consultation on the care of the elders in community clinics. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49:260–262. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pugh MJV, Rosen AK, Montez-Rath M, et al. Potentially inappropriate prescribing for the elderly: Effects of geriatric care at the patient and health care system level. Med Care. 2008;46:167. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318158aec2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorbero ME, Saul ML, Hangsheng L, et al. Are geriatricians more efficient than pther physicians at managing inpatient care for elderly patients? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60:869–876. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03934.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pawlson LG. Hospital length of stay of frail elderly patients. Primary care by general internists versus geriatricians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1988;36:202–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Fried LP, et al. Which patients benefit the most from a geriatrician's care? Consensus among directors of geriatrics academic programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1796–1801. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheridan BC, Stearns SC, Rossi JS, et al. Three-year outcomes of multivessel revascularization in very elderly acute coronary syndrome patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1889. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guccione AA, Felson DT, Anderson JJ, et al. The effects of specific medical conditions on the functional limitations of elders in the Framingham study. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:351–358. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG, Baldwin LM, et al. The generalist role of specialty physicians. JAMA. 1998;279:1364–1370. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.17.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pham HH, Schrag D, O'Malley AS, et al. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1130–1139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa063979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caldwell D. Medicare physician identifiers: UPINs, PINs, and NPI numbers. Minneapolis: Research Data Assistance Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kautter J, Pope GC, Trisolini M, et al. Medicare physician group practice demonstration design: Quality and efficiency pay-for-performance. Health Care Financ Rev. 2007;29:15–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caldwell D. How to identify emergency room services in the Medicare claims data. Minneapolis: Research Data Assistance Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris DR, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199801000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Legler JM, et al. Development of a comorbidity index using physician claims data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:1258–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. Rural Urban Commuting Area-ZIP code approximation. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 27.U.S. Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin for counties: April 1, 2000 to july 1, 2009. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barosso G. University of Minnesota: Research Data and Assistance Center; 2006. Dual Medicare-Medicaid enrollees and the Medicare denominator file. Report No.: TN-010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Institute of Medicine. Retooling for an aging America: Building the health care workforce. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaMascus AM, Bernard MA, Barry P, et al. Bridging the workforce gap for our aging society: How to increase and improve knowledge and training. Report of an expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:343–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medical never-never land: 10 reasons why America is not ready for the coming age boom. Washington, DC: Alliance for Aging Research; 2002. [cited November 2, 2011]. Available from: http://www.agingresearch.org/content/article/detail/698. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geriatrics Workforce Policy Studies Center. Comparison of percent of USMDs, percent of filled first year positions, and private practice salaries for selected specialties. [cited January 30, 2011]; Available at: http://www.adgapstudy.uc.edu/figs_practice.cfm.

- 33.Weeks WB, Wallace AE. Return on educational investment in geriatrics training. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1940–1945. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, P.L. 2010. pp. 111–148. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Caring for an Aging America Act, S. 1095, 112th Cong; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boyd CM, Reider L, Frey K, et al. The effects of guided care on the perceived quality of health care for multi-morbid older persons: 18-month outcomes from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:235–242. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1192-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guterman S, Davis K, Stremikis K, et al. Innovation in Medicare and Medicaid will be central to health reform's success. Health Aff. 2010;29:1188–1193. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]