Summary

AMPK is a metabolic sensor that helps maintain cellular energy homeostasis. Despite evidence linking AMPK with tumor suppressor functions, the role of AMPK in tumorigenesis and tumor metabolism is unknown. Here we show that AMPK negatively regulates aerobic glycolysis (the Warburg effect) in cancer cells, and suppresses tumor growth in vivo. Genetic ablation of the α1 catalytic subunit of AMPK accelerates Myc-induced lymphomagenesis. Inactivation of AMPKα in both transformed and non-transformed cells promotes a metabolic shift to aerobic glycolysis, increased allocation of glucose carbon into lipids, and biomass accumulation. These metabolic effects require normoxic stabilization of the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), as silencing HIF-1α reverses the shift to aerobic glycolysis and the biosynthetic and proliferative advantages conferred by reduced AMPKα signaling. Together our findings suggest that AMPK activity opposes tumor development, and its loss fosters tumor progression in part by regulating cellular metabolic pathways that support cell growth and proliferation.

Introduction

Genetic lesions that drive cancer progression affect key biological control points including cell cycle entry, DNA damage checkpoints, and apoptosis. However, the initiation of uncontrolled proliferation also presents a significant bioenergetic challenge to cancer cells; they must generate enough energy and acquire or synthesize biomolecules at a sufficient rate to meet the demands of proliferation. It is now appreciated that many of the predominant mutations observed in cancer also control tumor cell metabolism (Levine and Puzio-Kuter, 2010), suggesting that oncogene and tumor suppressor networks influence metabolism as part of their mode of action. One of the primary metabolic changes observed in proliferating cells is increased catabolic glucose metabolism. Many tumor cells adopt a metabolic phenotype characterized by high rates of glucose uptake and lactate production regardless of oxygen concentration, a phenomenon commonly referred to as the “Warburg Effect” (Vander Heiden et al., 2009). While the energetic yield per molecule of glucose is much lower for aerobic glycolysis compared to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), the metabolic shift towards the Warburg effect appears to confer both bioenergetic and biosynthetic advantages to proliferating cells by promoting increased non-oxidative ATP production and generating metabolic intermediates from glucose that are important for cell growth (DeBerardinis et al., 2008).

Appreciation of the generality of the Warburg effect in cancer has stimulated the broader concept that a “metabolic transformation” accompanies tumorigenesis (Jones and Thompson, 2009). However, the metabolic control points and signal transduction pathways that regulate the Warburg Effect during tumorigenesis and their importance to tumor progression in vivo remain poorly defined. The AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a highly conserved Ser/Thr protein kinase complex that plays a central role in the regulation of cellular energy homeostasis. AMPK is activated in response to declining fuel supply, and functions in the decision to allocate nutrients towards catabolic/energy-producing or anabolic/growth-promoting metabolic pathways (Hardie, 2011). From a metabolic standpoint, AMPK promotes ATP conservation under conditions of metabolic stress by activating pathways of catabolic metabolism such as autophagy (Egan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2011) and inhibiting anabolic processes including lipid biosynthesis (Davies et al., 1990), TORC1-dependent protein biosynthesis (Gwinn et al., 2008; Inoki et al., 2003), and cell proliferation (Imamura et al., 2001; Jones et al., 2005). AMPK activity has been recently linked to stress resistance and survival in tumor cells (Jeon et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2012).

Due to its involvement in cellular stress resistance, AMPK has been linked to the regulation of tumorigenesis (Shackelford and Shaw, 2009). The upstream AMPK-activating kinase LKB1 is a tumor suppressor gene inactivated in patients with Peutz-Jegher’s syndrome (Alessi et al., 2006), a condition that predisposes patients to gastrointestinal polyps and malignant tumors (Giardiello et al., 1987; Hearle et al., 2006). Cells lacking LKB1 display defective energy-dependent AMPK activation (Hawley et al., 2003; Shaw et al., 2004b). Additional evidence supporting a tumor suppressor function for AMPK is derived from experiments with the glucose-lowering drug metformin, which acts in part by activating AMPK (Zhou et al., 2001). Treatment of animals harboring tumor xenografts or naturally arising lymphomas with metformin can delay tumor progression (Buzzai et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2008). However, to date the role of AMPK in tumorigenesis and tumor metabolism has remained unclear.

In this work we demonstrate that loss of AMPK signaling cooperates with Myc to accelerate tumorigenesis. Moreover, silencing AMPKα in both transformed and non-transformed cells results in a switch to aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect) in the absence of energetic crisis. This metabolic shift is characterized by increased glucose uptake, redirection of carbon flow towards lactate, increased flux of glycolytic intermediates towards lipid biosynthesis, and an increase in net biomass (size). Induction of this metabolic shift is dependent on HIF-1α, as silencing of HIF-1α by shRNA ablates the effects of AMPKα loss on aerobic glycolysis, biosynthesis, and tumor growth in vivo. Our findings indicate that AMPK is a metabolic sensor essential for the coordination of metabolic activities that support cell growth and proliferation in cancer cells, and that disruption of AMPK signaling promotes metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells to drive the Warburg effect and influence tumor development and progression in vivo.

Results

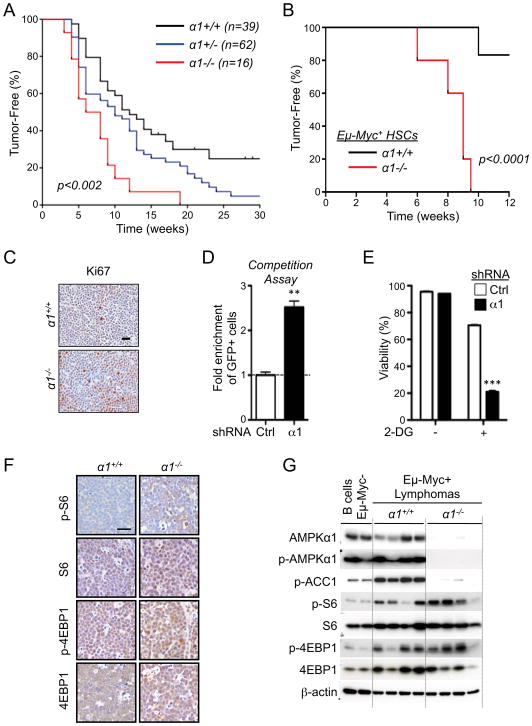

Loss of AMPKα1 accelerates Myc-driven lymphomagenesis

AMPK lies downstream (Hawley et al., 2003; Shaw et al., 2004b) and upstream (Inoki et al., 2003) of known tumor suppressors (LKB1 and TSC2, respectively), but its role in tumorigenesis has remained unclear. To address this question we generated Eμ-Myc transgenic mice (Adams et al., 1985) harboring a mutation in the gene that encodes AMPKα1 (prkaa1), which is the sole catalytic subunit expressed in B lymphocytes (Fig. S1A). Latency to tumor development was monitored by palpation, and both tumor-free survival and overall lifespan were monitored. Compared to Eμ-Myc control mice, Eμ-Myc animals lacking AMPKα1 displayed accelerated lymphomagenesis with a median tumor onset of 7 weeks (Fig. 1A) and a maximum overall survival rate of 20 weeks (Fig. S1B). Eμ-Myc mice heterozygous for AMPKα1 displayed an intermediate phenotype, with a median tumor onset of 10 weeks (Fig. 1A). Lymph node tumors isolated from Eμ-Myc/α1+/+ and Eμ-Myc/α1−/− mice displayed prominent B220/CD45R staining, indicating that tumors arising in these animals were of B cell origin (Fig. S1C); however, all AMPKα1-deficient B220+ lymphomas examined lacked surface immunoglobulin (sIg) expression, suggesting that these tumors were pre-B cell tumors, rather than mature B cell tumors (Fig. S1C).

Figure 1. AMPKα1 cooperates with Myc to promote lymphomagenesis.

A) Kaplan-Meier curves showing latency to tumor development in Eμ-Myc transgenic mice deficient (α1−/−, red), heterozygous (α1+/−, blue) or wild-type (α1+/+, black) for AMPKα1. B) Kaplan-Meier curves showing latency to tumor development in chimeric mice reconstituted with Eμ-Myc/α+/+ (α1+/+, black) or Eμ-Myc/α1−/− (α1−/−, red) HSCs (n=5 per group). C) Representative histological sections of Eμ-Myc/α+/+ and Eμ-Myc/α1−/− lymphomas stained for the proliferation marker Ki-67. D) Competition assay of Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells expressing GFP and control (Ctrl) or AMPKα1-specific (α1) shRNAs. Data are expressed as the fold enrichment in GFP+ to GFP− cells after 6 days of growth. E) Viability of control (Ctrl) or AMPKα1 shRNA-expressing Eμ-Myc lymphomas cells after 24h treatment with 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG, 15 mM). F) Immunohistochemical analysis of representative Eμ-Myc/α+/+ and Eμ-Myc/α1−/− lymphomas stained with antibodies to detect TORC1 activity (total and phospho-ribosomal S6 (pS6, S240/244), or total and phospho-4EBP1 (p4EBP1, S37/46)). G) Immunoblot analysis of primary Eμ-Myc/α+/+ or Eμ-Myc/α1−/− lymphomas. Whole cell lysates prepared from sorted primary lymphoma cells were analyzed by immunoblot using the indicated antibodies. Each lane represents an independent tumor. Lysates from non-transformed B cells isolated from Eμ-Myc-negative mice are shown. **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

To assess whether the accelerated tumor onset observed in Eμ-Myc/α1−/− animals was due to a cell intrinsic effect of AMPKα1-deficiency in B cells, we generated chimeric mice using Eμ-Myc/α1+/+ or Eμ-Myc/α1−/− hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) to reconstitute lethally-irradiated wild-type mice (C57BL/6 background). All animals reconstituted with Eμ-Myc/α1−/− HSCs developed palpable lymphomas within 9 weeks of reconstitution, while only 20% of animals receiving Eμ-Myc/α1+/+ HSCs developed tumors 12 weeks post reconstitution (Fig. 1B). These data establish that specific loss of AMPKα1 in B cells can promote accelerated Myc-driven lymphomagenesis.

While lymph node tumors from both genotypes looked histologically similar by H&E staining (Fig. S1D), Eμ-Myc/α1−/− lymphomas displayed increased proliferation marker Ki-67 staining in situ (Fig. 1C). Immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis revealed no major differences in tumor vascularization (measured by CD31 staining) or apoptosis (IHC for cleaved caspase-3) between AMPKα1-deficient and control Eμ-Myc tumors (Fig. S1E). We next silenced AMPKα1 in primary Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells using shRNA (Fig. S1F), and measured the impact of AMPKα1 levels on cell proliferation using an in vitro competition assay. Primary Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells were transduced with retroviral vectors co-expressing GFP and control or AMPKα1-specific shRNAs, and the percentage of GFP+ cells remaining after six days of culture was determined by flow cytometry. AMPKα1 shRNA-expressing cells displayed a competitive growth advantage in vitro over cells expressing control shRNA (Fig. 1D).

Activation of AMPK promotes cell survival in response to metabolic stress (Bungard et al., 2010; Buzzai et al., 2007; Jeon et al., 2012). To determine whether loss of AMPK renders Eμ-Myc tumors sensitive to metabolic stress, Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells expressing control or AMPKα1 shRNAs were treated with the glycolytic inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG) and cell viability measured after 24 hours. AMPKα1 shRNA-expressing lymphomas displayed normal viability under standard growth conditions but increased cell death in the presence of 2-DG (Fig. 1E). Together these data suggest that loss of AMPKα1 can enhance tumor development driven by oncogenic Myc in vivo, but is required to maintain tumor cell viability.

We next explored putative altered signaling events in AMPKα1-deficient lymphomas by IHC analysis of tumor sections. AMPKα, phospho-AMPKα and phospho-ACC (pACC) expression in tumor-bearing lymph nodes confirmed a complete loss of AMPK signaling in Eμ-Myc/α1−/− tumors (Fig. S1G). Similar to that observed in Lkb1+/− tissues (Shackelford et al., 2009; Shaw et al., 2004a), tumor tissue from Eμ-Myc/α1−/− mice displayed increased staining for S6 and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation (Fig. 1F), suggesting an increase in basal TORC1 signaling in AMPKα-null lymphomas in vivo. Similar data were observed via immunoblotting of primary lymphoma cells isolated immediately ex vivo from tumor-bearing lymph nodes. Both TORC1 and AMPK activity (as determined by ACC phosphorylation) were elevated in Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells compared to normal B cells (Fig. 1G). When comparing Eμ-Myc/α 1+/+ and Eμ-Myc/α1−/−; lymphomas directly, pACC levels were ablated in α1−/− tumors, while TORC1 activity was increased in α1−/− tumors with some variability in levels of both S6 and 4E-BP1 phosphorylation between α1−/− tumor samples (Fig. 1G).

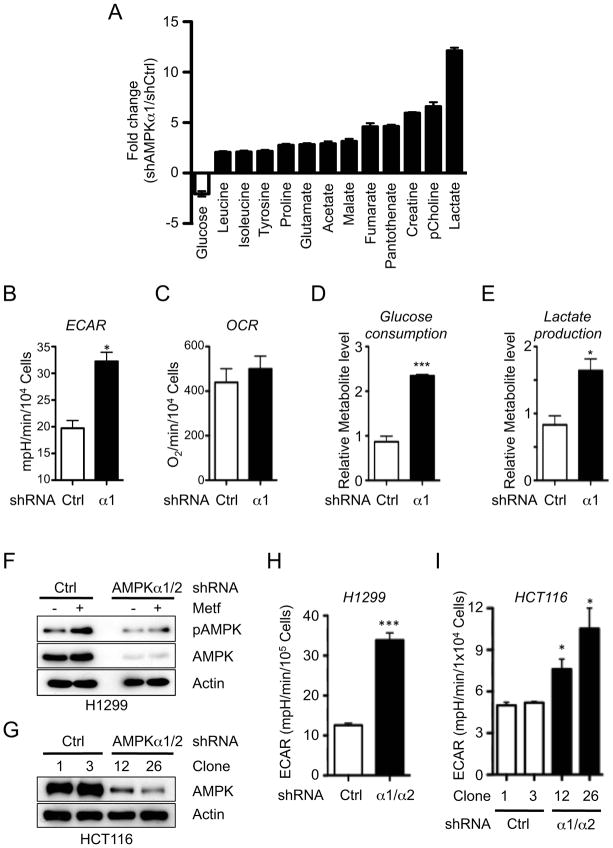

Loss of AMPKα signaling enhances the Warburg effect in cancer cells

AMPK sits at a central node in the regulation of catabolic and anabolic metabolism (Hardie et al., 2012). To address the role of AMPK in regulating the metabolism of lymphoma cells we conducted a targeted metabolomic analysis of Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells using NMR spectrometry. Employing a stringent statistical cutoff (p<0.01) and metabolites displaying a 2-fold change in abundance, we identified 13 metabolites showing differential abundance in shAMPKα1 lymphoma cells (Fig. 2A). By these criteria glucose was the only metabolite significantly decreased in shAMPKα1 lymphoma cells, while lactate displayed the greatest increase (Fig. 2A). Lymphomas expressing AMPKα1 shRNA displayed an elevated extracellular acidification rate (ECAR, Fig. 2B), an index of lactate production (Wu et al., 2007), but displayed no significant difference in their oxygen consumption rate (OCR, Figs. 2C and S2A). AMPKα1 shRNA-expressing Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells also displayed increased glucose consumption (Fig. 2D) and lactate production (Fig. 2E) relative to control lymphoma cells, a metabolic signature consistent with the Warburg effect.

Figure 2. Loss of AMPK signaling enhances the Warburg Effect in cancer cells.

A) NMR metabolite profile of AMPKα-deficient lymphomas. Data are expressed as relative metabolite levels for shAMPKα1-versus shCtrl-expressing cells (p<0.01) for samples in quintuplicate. Open bars, decreased metabolites; closed bars, increased metabolites. B–C) Extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) (B) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR, C) for proliferating shControl (Ctrl) or shAMPKα1 (α1) Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells. Data represent the mean ± SEM for quadruplicate samples. D–E) Glucose consumption (D) and lactate production (E) of shControl (Ctrl) or shAMPKα1 (α1) Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells grown as in (B–C). (F) Immunoblot of AMPKα T172 phosphorylation and total AMPKα levels in H1299 cell clones expressing control (shCtrl) or AMPKα1/α2-specific shRNAs following treatment with Metformin (5 mM, 1 hour). G) Knockdown of AMPKα1 and α2 in HCT116 cells. (H–I) ECAR of H1299 (H) or HCT116 (I) cell clones expressing control (shCtrl) or AMPKα-specific (α1/α2) shRNAs grown under standard conditions. *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001.

To assess whether reducing AMPK activity is sufficient to enhance the Warburg effect in cancer cells we silenced AMPK in two independent cell lines, H1299 (non-small cell lung carcinoma) and HCT116 (colon carcinoma). Expression of shRNAs targeting both the α1 and α2 subunits of AMPK reduced total AMPKα protein expression in these cell lines (Fig. 2F–G), and AMPKα silencing promoted a significant increase in the basal ECAR of both H1299 (Fig. 2H) and HCT116 cells (Fig. 2I). Lactate production was also elevated in H1299 and HCT116 cells expressing AMPKα shRNA (Fig. S2B–C). Taken together with our observations using AMPKα1 shRNA-expressing Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells, these data suggest that downregulation of AMPK signaling is sufficient to enhance the Warburg effect in transformed cells.

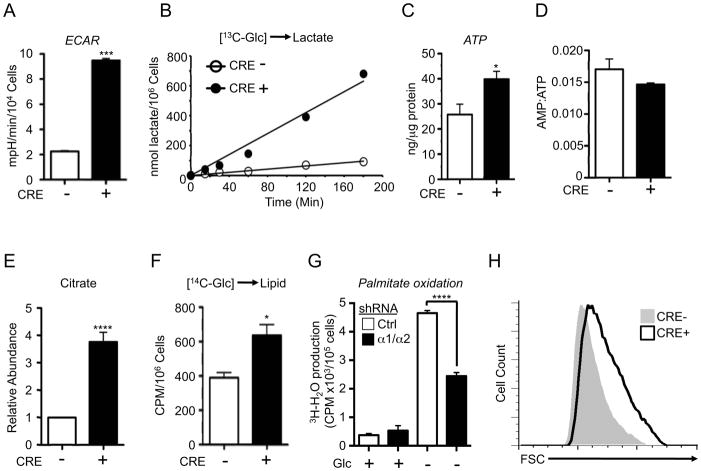

Loss of AMPK signaling promotes increased ATP levels and anabolic metabolism

Given the increased metabolic demands of cell proliferation, we hypothesized that an intact AMPK signaling pathway may function to coordinate metabolism and biosynthesis in actively dividing cells. To address this we generated non-transformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) deficient for AMPKα. Using MEFs deficient for prkaa1 and harboring a conditional mutation for prkaa2 (denoted hereafter as α1−/−, a2fl/fl), we generated paired isogenic cell lines that possess or completely lack AMPK catalytic activity depending on expression of Cre recombinase (Fig. S3A). MEFs lacking AMPKα (Cre+) displayed increased glucose consumption (Fig. S3B), lactate production (Fig. S3C), and ECAR (Fig. 3A) relative to control (Cre−) cells. We next traced the metabolic fate of 13C-glucose in these cells, and found that AMPKα-deficient cells displayed a progressive increase in the m+3 isotopologue of lactate (13C3-lactate) derived from glucose over time (Fig. 3B), corresponding to a 6-fold increase in the glucose-to-lactate conversion rate.

Figure 3. Loss of AMPK signaling promotes increased biosynthesis.

A) ECAR of control (Cre−, open bar) or AMPKα-null (Cre+, closed bar) MEFs cultured under standard growth conditions. Values shown are the mean ± SEM for samples in quadruplicate. B) Glucose-to-lactate conversion in control (Cre−) or AMPKα-deficient (Cre+) MEFs. Cells were cultured with medium containing uniformly labeled 13C-glucose, and enrichment of 13C-lactate (m+3) in the extracellular medium was measured at the indicated time points. C) ATP content of control (Cre−) or AMPKα-null (Cre+) MEFs as measured by HPLC. D) AMP:ATP ratios for cells in (C). E) Intracellular citrate levels of control (Cre−) or AMPKα-null (Cre+) MEFs as determined by GC-MS. F) Glucose-derived lipid biosynthesis in control (Cre−) or AMPKα-null (Cre+) MEFs. Cells were incubated with uniformly labeled 14C-glucose for 72 hours, and radioactive counts in extracted lipids measured. G) Palmitate oxidation by MEFs expressing control (Ctrl) or AMPKα1/α2 shRNAs. MEFs were grown in the presence (+) or absence (−) of glucose for 24 hours, followed by culture with [9,10-3H]-palmitic acid and 200 μM etomoxir. Tritiated water produced from palmitate oxidation was measured. H) Forward scatter (FSC) of control (Cre−, grey histogram) or AMPKα-deficient (Cre+, open histogram) MEFs. *, p<0.05; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

One possibility for the increased ECAR in cells lacking AMPK activity could be a compensatory response to low cellular energy triggered by AMPK loss. To address this we measured the adenylate energy charge in unstressed, actively growing MEFs by HPLC. Remarkably, cellular ATP levels were elevated in AMPKα-deficient MEFs relative to controls (Fig. 3C). In contrast, the AMP:ATP ratio was not significantly affected by the loss of AMPK activity in proliferating cells (Fig. 3D), suggesting no significant change in basal cellular energy charge when AMPKα is absent.

The metabolic shift to the Warburg effect facilitates the redirection of glucose-derived carbon towards biosynthetic pathways to generate biomass (Vander Heiden et al., 2009), including extrusion of glucose-derived citrate from the citric acid cycle (CAC) for lipid biosynthesis (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2005). Consistent with this, total citrate levels were elevated in AMPKα-deficient cells relative to control cells as determined by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Fig. 3E). We next measured glucose-dependent lipid biosynthesis by culturing MEFs with D-[6-14C]-glucose, and found that AMPKα-deficient cells displayed increased 14C-labelling in lipids (Fig. 3F). Decreased ACC phosphorylation in AMPKα-null cells is predicted to contribute to lipid synthesis, but may also decrease fatty acid oxidation. Baseline palmitate oxidation remained low in proliferating cells grown under full glucose conditions regardless of AMPK expression (Fig. 3G). However, cells expressing AMPKα shRNA displayed a reduced ability to oxidize lipid upon complete removal of glucose (Fig. 3G), suggesting that AMPK is required to trigger catabolic lipid metabolism specifically under nutrient poor conditions.

Consistent with shunting of glucose-derived carbon towards biosynthesis in proliferating cells, AMPKα-null MEFs displayed a 20% increase in median cell size as determined by forward scatter (FSC) using flow cytometry (Fig. 3H). TORC1 is a central regulator of cell size (Laplante and Sabatini, 2009), and AMPK can negatively regulate TORC1 activity under energy stress (Inoki et al., 2003; Shaw et al., 2004a). Consistent with this, the AMPK agonist AICAR suppressed TORC1 activity (as determined by reduced pS6 and p4E-BP levels) only in cells with wild type AMPKα (Fig. S3D). Notably, growth factor-dependent TORC1 activity in cells was similar regardless of AMPKα status (Fig. S3E), suggesting the existence of TORC1-independent pathways of biomass regulation in AMPKα-deficient cells.

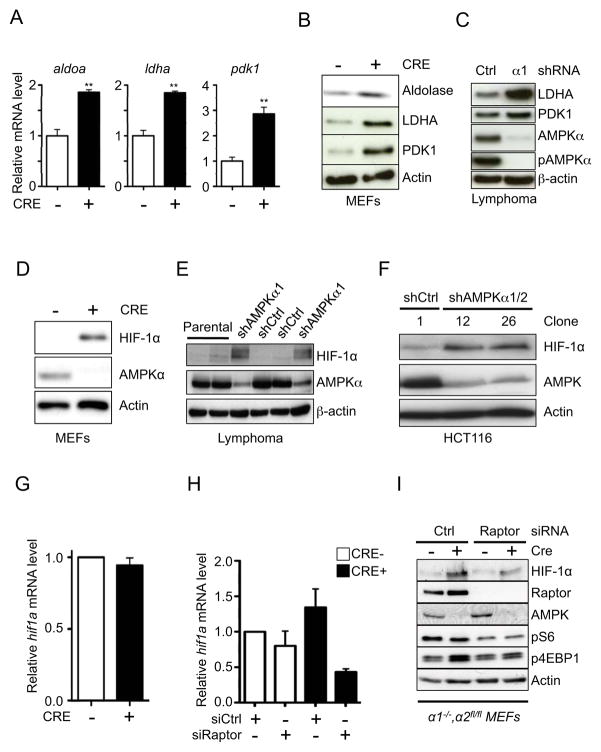

Loss of AMPKα promotes a glycolytic signature and increased HIF-1α expression

We next investigated potential mechanisms governing the glycolytic phenotype associated with AMPKα-deficient cells. We first used quantitative PCR (qPCR) to examine the relative levels of mRNA transcripts encoding for proteins involved in glycolytic regulation. AMPKα-null MEFs displayed a glycolytic gene signature marked by increased mRNA expression of Aldolase A (aldoa), Lactate dehydrogenase A (ldha), and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (pdk1) (Figs. 4A and S4A), a pattern of gene expression also displayed by shAMPKα1 lymphoma cells (Fig. S4B). Elevated Aldolase, LDHA and PDK1 protein levels were also detected in AMPKα-deficient MEFs (Fig. 4B) and shAMPKα1 lymphoma cells (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. Loss of AMPK promotes a glycolytic signature and increased HIF-1α expression.

A) Relative expression of aldoa, ldha, and pdk1 mRNA in control (Cre−, open bar) or AMPKα-null (Cre+, closed bar) MEFs as determined by qPCR. Transcript levels were determined relative to actin mRNA levels, and normalized relative to control (Cre−) cells. B–C) Immunoblot analysis of Aldolase, LDHA, and PDK1 protein levels in whole cell lysates from control (Cre−) and AMPKα-null (Cre+) MEFs (B) or shControl (Ctrl) and shAMPKα1 (α1)-expressing Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells (C). D–F) Immunoblot of HIF-1α protein levels in whole cell lysates from control (Cre−) and AMPKα-null (Cre+) MEFs (D), shControl (shCtrl) and shAMPKα1-expressing Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells (E), or HCT116 cell clones expressing control (shCtrl) or AMPKα-specific (shAMPKα1/2) shRNAs (F). All cells were grown under 20% O2. G) Relative hif1a mRNA expression in control (Cre−) or AMPKα-null (Cre+) MEFs as determined by qPCR. H–I) Expression of hif-1α mRNA (H) and protein levels (I) for control (Cre−) or AMPKα-null (Cre+) MEFs transfected with siRNAs targeting Raptor. Protein lysates were also analyzed for pS6 and p4EBP levels by immunoblot. Raptor, AMPKα, and actin levels are shown as controls. **, p<0.01.

PDK1 curbs pyruvate flux to Acetyl-CoA and entry into the TCA cycle by antagonizing the action of the pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex (Kim et al., 2006; Papandreou et al., 2006). Thus, elevated PDK1 levels observed in AMPKα-deficient cells may be predicted to affect glucose flux to citrate. To measure this we cultured control or AMPKα-null MEFs in medium containing uniformly labeled [13C]-glucose and measured 13C enrichment in citrate by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Glucose-derived pyruvate is converted to Ac-CoA by PDH. Subsequent condensation of [1,2-13C]-Ac-CoA with oxaloacetate (OAA) yields citrate with 2 additional mass units (m+2), while an additional turn through the TCA cycle produces citrate(m+4). We observed modest increases in levels of unlabeled citrate in AMPKα-null MEFs relative to control cells, as well as reduced citrate(m+4) labeling from [13C]-glucose (Fig. S4C). 13C enrichment in citrate was similar between control and AMPKα-null MEFs when [13C]-glutamine was used as carbon source (Fig. S4D).

Several of the enzymes elevated in AMPKα-deficient cells are known targets of the transcription factor HIF-1α, one of the central regulators of glycolysis induced by hypoxia (Keith et al., 2012; Semenza, 2011). We observed elevated HIF-1α protein levels under normoxia following acute AMPKα deletion in our isogenic cell lines (Fig. 4D), consistent with previous work demonstrating elevated HIF-1α protein expression in cells with chronic depletion of AMPKα (Shackelford et al., 2009). Moreover, shRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPKα1 in Eμ-Myc lymphomas (Fig. 4E) or HCT116 cells (Fig. 4F) promoted normoxic HIF-1α protein stabilization. Levels of hif1a mRNA were unchanged in AMPKα-null MEFs relative to controls (Fig. 4G), suggesting that reducing AMPK activity is sufficient to increase HIF-1α protein levels in cancer cells under normoxic conditions independent of mRNA levels.

TORC1 signaling has been linked to control of HIF-1α expression through differential regulation of its translation (Choo et al., 2008). To examine the contribution of TORC1 signaling to HIF-1α stabilization in AMPKα-deficient cells, we silenced the TORC1 binding partner Raptor using siRNA. Treatment with Raptor siRNA significantly reduced hif1a mRNA levels in both control and AMPKα-deficient MEFs, with the latter demonstrating a large drop in hif1a mRNA expression upon Raptor depletion (Fig. 4H). Moreover, transient knockdown of Raptor in AMPKα-deficient MEFs reduced HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 4I), and reduced the expression of the HIF-1α targets aldoa (Fig. S4E) and ldha (Fig. S4F).

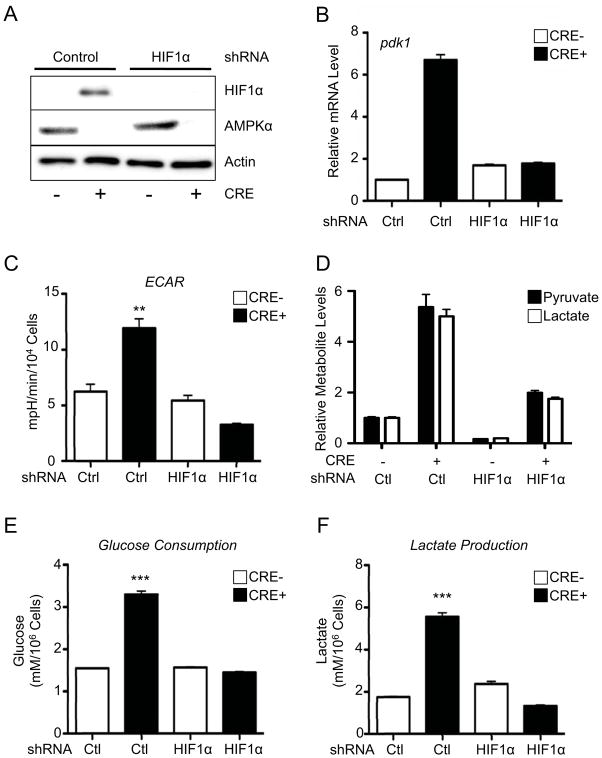

AMPKα-dependent effects on glycolysis are mediated by HIF-1α

To determine the contribution of HIF-1α to the glycolytic phenotype observed in AMPKα-null cells, we stably silenced HIF-1α in control (Cre−) or AMPKα-deficient (Cre+) MEFs using RNAi. Expression of HIF-1α shRNA ablated HIF-1α protein expression in AMPKα-deficient MEFs under normoxia (Fig. 5A), and blocked CoCl2-dependent induction of HIF-1α protein in both AMPKα-deficient and control cells (Fig. S5A). Expression of HIF-1α shRNA reduced pdk1 mRNA in AMPKα-null cells to control levels, demonstrating that expression of this shRNA could block HIF-1α-dependent transcription (Fig. 5B). We next determined whether silencing HIF-1α could reverse the Warburg effect triggered by loss of AMPKα activity. While HIF-1α shRNA had little effect on the ECAR of control cells, silencing HIF-1α in AMPKα-deficient cells lowered the ECAR below control levels (Fig. 5C). GC-MS analysis revealed dramatic reductions in intracellular pyruvate and lactate in AMPKα-deficient cells expressing HIF-1α shRNA relative to control shRNA (Fig. 5D). Moreover, silencing HIF-1α ablated the enhanced levels of glucose consumption (Fig. 5E) and lactate production (Fig. 5F) displayed by AMPKα-deficient cells. Similar reductions in glucose consumption and lactate production were observed in AMPKα-deficient MEFs transfected with HIF-1α siRNA (Fig. S5B–D). Silencing Raptor in AMPKα-deficient MEFs, which partially reduced HIF-1α protein levels (Fig. 4I), led to slight reductions in lactate production (Fig. S5E) and ECAR (Fig. S5F).

Figure 5. HIF-1α mediates the effects of AMPK loss on aerobic glycolysis.

A) HIF-1α protein expression in control (Cre−) or AMPKα-deficient (Cre+) MEFs also expressing control or HIF-1α-specific shRNAs. Cells were grown under normoxic conditions (20% O2). AMPKα and actin protein levels are shown. B) Relative expression of pdk1 mRNA in control (Cre−) or AMPKα-deficient (Cre+) MEFs expressing control (Ctrl) or HIF-1α-specific shRNAs. C–F) AMPK-dependent changes in the Warburg Effect are dependent on HIF-1α. C) ECAR of control (Cre−) or AMPKα-deficient (Cre+) MEFs expressing control (Ctrl) or HIF-1α-specific shRNAs grown under normoxic conditions (20% O2). Relative intracellular pyruvate (closed bars) and lactate (open bars) levels (D), glucose consumption (E), and lactate production (F) for cells grown as in (C). **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001.

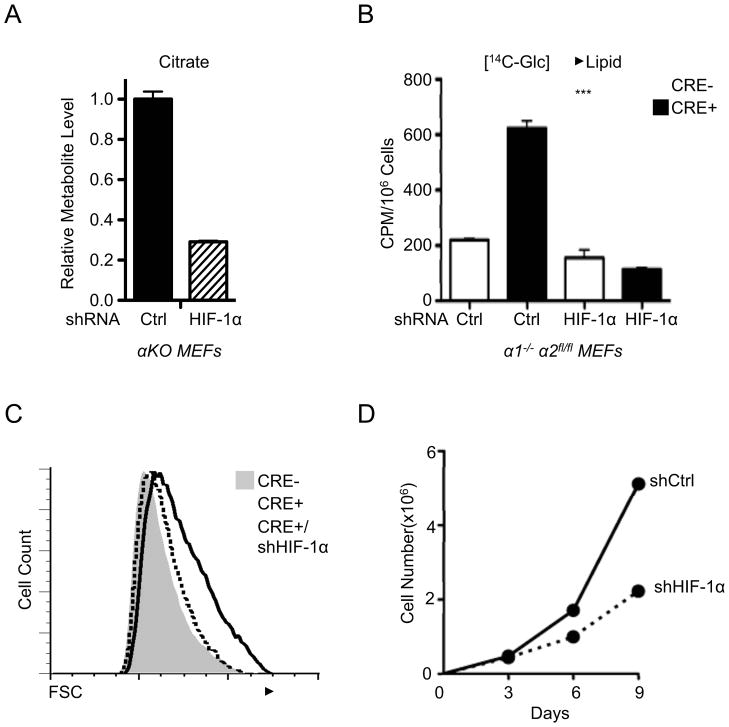

HIF-1α drives increased biosynthesis in AMPKα-null cells

Next we determined the impact of HIF-1α expression on cellular biosynthesis and proliferation induced by AMPKα loss. Silencing HIF-1α reduced intracellular citrate in AMPKα-deficient cells by approximately 70% (Fig. 6A), restoring citrate levels to that observed in control cells. Moreover, suppression of HIF-1α dramatically reduced glucose-dependent lipogenesis in AMPKα-deficient MEFs (Fig. 6B). Suppression of HIF-1α had little effect on glucose-dependent lipogenesis in control cells (Fig. 6B), consistent with the fact that HIF-1α protein is maintained at low levels in these cells under normoxia.

Figure 6. HIF-1α drives increased biosynthesis and proliferation of AMPKα-null cells.

A) Relative citrate abundance in metabolite extracts from AMPKα-deficient (αKO) MEFs expressing control (Ctrl) or HIF-1α-specific shRNAs as determined by GC-MS. B) Lipid biosynthesis in AMPKα-deficient MEFs with HIF-1α knockdown. Control (Cre−) or AMPKα-deficient (Cre+) MEFs expressing control (Ctrl) or HIF-1α-specific shRNAs were incubated with uniformly labeled 14C-glucose for 72 hours, and radioactive counts in extracted lipids were measured. C) Cell size of control (grey histogram), AMPKα-null (open histogram), and AMPKα-null MEFs expressing HIF-1α shRNA (dashed histogram) as measured by FSC intensity. D) Growth curves of AMPKα-null MEFs expressing control (shCtrl) or HIF-1α-specific (shHIF-1α) shRNAs grown under 20% O2. Growth curves were determined using a 3T3 growth protocol and cell counts measured by trypan blue exclusion. ***, p<0.001.

Given that aberrant HIF-1α expression drives both enhanced glycolysis and glucose-derived lipogenesis, we reasoned that the increased size of AMPKα-deficient cells may be attributed to HIF-1α-dependent changes in anabolic metabolism. While loss of AMPKα promotes increased cell size, silencing HIF-1α restored the size of AMPKα-deficient MEFs to that of control cells (Fig. 6C). Notably, rapamycin treatment also reduced the size of AMPKα-deficient MEFs (Fig. S6A). However, this treatment also reduced hif1a mRNA levels in cells regardless of AMPKα expression (Fig. S6B), suggesting rapamycin may exert its effects in part through regulation of HIF-1α mRNA. Finally, suppression of HIF-1α signaling in AMPKα-deficient cells reduced their overall rate of proliferation (Fig. 6D). Collectively the data suggest that AMPK negatively regulates the metabolic (Warburg effect) and biosynthetic programs of proliferating cells through the inhibition of HIF-1α function.

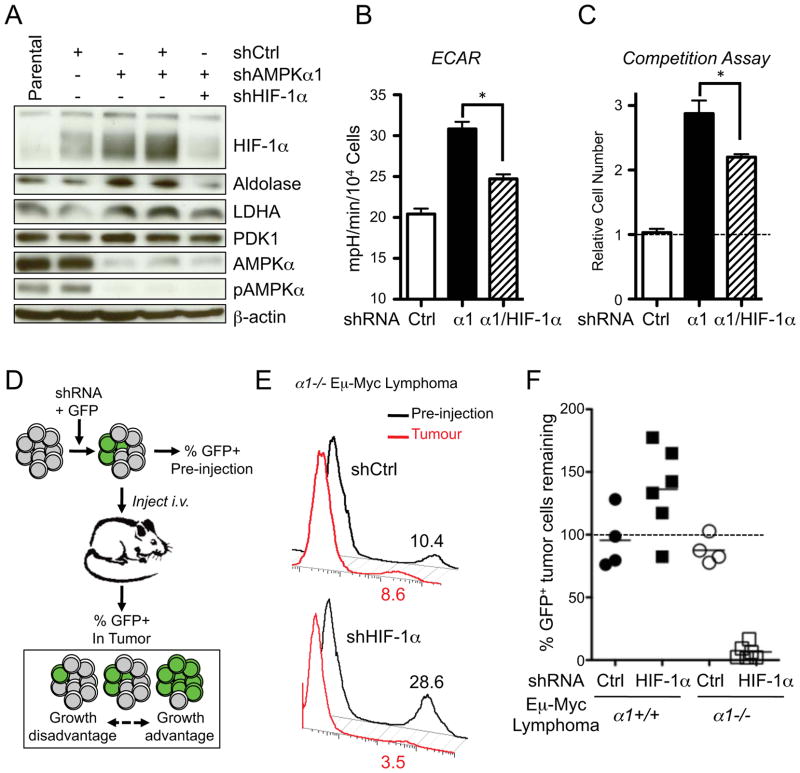

HIF-1α is required for the progression of AMPKα1-deficient lymphomas

Our earlier results (Fig. 2) indicate that reduced AMPK signaling synergizes with Myc to promote the Warburg effect in lymphoma. To determine the contribution of HIF-1α to the glycolytic phenotype of Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells we stably expressed HIF-1α-specific shRNAs in Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells with silenced AMPKα1. Silencing HIF-1α in AMPKα1 shRNA-expressing cells reduced HIF-1α protein expression to control levels (Fig. 7A). Protein levels of the HIF-1α targets Aldolase and LDHA expression also decreased when HIF-1α was silenced in AMPKα1 shRNA-expressing lymphomas (Fig. 7A). We next examined metabolic activity in these lymphomas. Expression of AMPKα1 shRNA increased cellular ECAR as expected, while silencing HIF-1α reduced this enhanced ECAR response by 60% (Fig. 7B). Finally, lymphoma cells expressing both AMPKα1 and HIF-1α shRNA showed decreased proliferation relative to cells expressing AMPKα1 shRNA alone (Fig. 7C).

Figure 7. HIF-1α mediates the metabolic and tumorigenic effects induced by AMPKα1 loss.

A) Immunoblots of whole cell lysates from Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells expressing AMPKα1 and HIF-1α shRNAs. Cells were cultured under standard conditions (25 mM glucose, 20% O2). Blots were probed with antibodies to the indicated proteins. B) ECAR of Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells expressing control (Ctrl), AMPKα1 (α1), or both AMPKα1 and HIF-1α (α1/HIF-1α) shRNAs and grown under standard conditions. C) Competition assay of Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells infected with retrovirus expressing GFP and control, AMPKα1 (α1), or both AMPKα1 and HIF-1α (α1/HIF-1α) shRNAs. The data are expressed as the relative increase in GFP+ to GFP− cells after 6 days of culture. D) Schematic of in vivo lymphoma competition assay. E) Representative histograms of GFP expression for AMPKα1−/− Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells prior to injection into recipient mice (Pre-injection, black) or isolated from lymph node tumors (Tumor, red). Numbers indicate the percentage of GFP+ cells. F) Percent recovery of GFP+ tumor cells from individual Eμ-Myc/α1+/+ (black) or Eμ-Myc/α1−/− (white) tumors expressing the indicated shRNAs. *, p<0.05.

We next tested the requirement for HIF-1α for tumor progression in vivo. Primary control or AMPKα-deficient Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells were transduced with retroviral vectors expressing GFP and either control or HIF-1α shRNAs, and the percentage of GFP+ lymphoma cells (expressing the shRNA of interest) was determined by flow cytometry prior to transplantation into recipient mice and following lymphoma formation (Fig. 7D). Expression of control shRNA did not dramatically alter the fraction of GFP+ Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells regardless of genotype (Fig. 7E,F). Interestingly, silencing HIF-1α in Eμ-Myc lymphomas promoted a general increase in the number of GFP+ tumor cells, although this did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 7F). However, lymphoma cells expressing HIF-1α shRNA were selectively depleted in AMPKα-null tumors (Fig. 7E,F). Collectively these data suggest that loss of AMPK signaling promotes a metabolic and growth advantage in lymphoma cells, and that HIF-1α is required for the growth of AMPKα1-null tumors in vivo.

Discussion

AMPK is a cellular energy sensor that coordinates metabolic activities in many tissues. Under conditions of energetic stress, AMPK activation suppresses cell growth and proliferation, leading to speculation that AMPK may function as part of a tumor suppressor pathway (Hardie, 2011; Shackelford and Shaw, 2009). Here we provide the first genetic evidence that AMPKα displays tumor suppressor activity in vivo. Loss of AMPK signaling cooperates with oncogenic Myc to enhance tumorigenesis in a mouse model of lymphomagenesis, suggesting that AMPK may function as a tumor suppressor (Fig. 1). Moreover, we demonstrate that AMPK is a negative regulator of both aerobic glycolysis and cellular biosynthesis in cancer cells. Cells deficient for the catalytic alpha subunit(s) of AMPK display increased aerobic glycolysis marked by increased lactate production from glucose (Figs. 2 and 3), and downregulation of AMPK activity is sufficient to induce the Warburg Effect in cancer cells (Fig. 2). We find that HIF-1α is a key mediator of AMPK-dependent effects on cellular metabolism. Reducing AMPKα levels in cells leads to increased HIF-1α protein levels under normoxia in both transformed and non-transformed cells (Fig. 4), and HIF-1α is required to drive both the Warburg effect and the growth of AMPKα1-deficient lymphomas in vivo (Fig. 5–7). The results presented here suggest that the downregulation of AMPK activity eliminates a key metabolic checkpoint that normally antagonizes anabolic pro-growth cellular metabolism. Thus, AMPK may act in cancer cells as a metabolic gatekeeper that functions to establish metabolic checkpoints that limit cell division, and its loss of function can enhance both tumorigenesis and tumor progression.

All cells must manage their energetic resources to survive. We and others have established that AMPK is the central mediator of a metabolic cell cycle checkpoint activated in response to nutrient limitation in mammalian cells (Gwinn et al., 2008; Inoki et al., 2003; Jones et al., 2005). However, programs of ATP production and macromolecular synthesis must also be coordinated in proliferating cells to ensure proper cell division. The data presented here suggest that AMPK functions to regulate metabolic homeostasis in proliferating cells in the absence of acute energetic stress. Isogenic MEFs or cancer cells lacking AMPKα activity display a metabolic shift towards aerobic glycolysis, thus allowing cancer cells to engage aerobic glycolysis for ATP production and divert glucose-derived CAC intermediates towards lipid biosynthesis to support increased cell growth. AMPK may also influence lipid biosynthesis through regulation of ACC and other lipogenic enzymes, possibly through its effects on SREBP-1 (Li et al., 2011). Thus, defective AMPKα signaling promotes the re-wiring of metabolic pathways to favor cell growth pathways.

Interestingly our data provide evidence that AMPKα-deficient tumors display increased activation of the TORC1 targets S6 and 4E-BP1, suggesting that AMPK, as opposed to other AMPK-related kinases, may be the key TORC1 regulator downstream of LKB1 in tumors. Consistent with past work (Inoki et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2004a), we find that AMPK functions to downregulate TORC1 activity specifically under conditions of energetic stress, when it is desirable to suppress ATP-consuming processes such as mRNA translation. This may provide a metabolic advantage to proliferating cells, where the loss of AMPK signaling promotes increased ATP production and resource accumulation without affecting the mitogenic properties of TORC1. By concurrently silencing AMPK while maintaining TORC1 signaling, cells may effectively bypass endogenous brakes on cellular metabolism, supporting increased tumor cell growth and proliferation.

Our work here establishes HIF-1α as an key mediator of the metabolic transformation triggered by reduced AMPKα activity in cancer cells. We show that downregulation of AMPK signaling is sufficient to induce normoxic HIF-1α stabilization and enhance the Warburg effect. TORC1 activity appears to contribute in part to this process, as silencing the mTORC1 binding partner Raptor reduces levels of hif1a mRNA in AMPKα-deficient cells. However, silencing Raptor moderately reduces HIF-1α protein levels and has a minimal effect on the glycolytic phenotype of AMPKα-deficient cells, suggesting that AMPK may regulate HIF-1α-dependent Warburg metabolism through additional mechanisms. Interestingly, TORC1 inhibition reduces hif1a mRNA and reduces glycolysis in cell regardless of AMPK expression, suggesting that TORC1 may function on a more global level as a positive regulator of glycolysis beyond specific effects on HIF-1α expression (Duvel et al., 2010). Given that TORC1 signaling is elevated in AMPKα1-deficient lymphomas, this may have implications for tumor metabolism in vivo. HIF-1α mRNA levels are unaffected by AMPK expression; thus, AMPK may affect normoxic HIF-1α protein expression either through decreased protein turnover or differential translation of HIF-1α mRNA (Choo et al., 2008). Overall we propose that AMPK functions to coordinate glycolytic and oxidative metabolism in proliferating cells by restricting HIF-1α function.

One consequence of AMPK loss in cells is enhanced flux of glucose-derived carbon to citrate for lipid biosynthesis, promoting biomass accumulation and increased cell size. This may appear counterintuitive, as HIF-1α-dependent upregulation of PDK1 under hypoxia is proposed to direct glucose-derived carbon away from the CAC (Kim et al., 2006; Papandreou et al., 2006). However, glucose-to-citrate flux is not blocked in AMPKα-null cells despite elevated PDK1 levels. Rather, the reduced levels of citrate(m+4) in AMPKα-null cells may result from increased use of glucose-derived citrate (m+2) for lipid biosynthesis. Reducing AMPK levels significantly decreases ACC1 inhibition in both tumor cells and tumor tissue, which would permit maximal activity of ACC1 for lipid biosynthesis. Thus, AMPK may regulate lipid biosynthesis and biomass accumulation on multiple levels: substrate availability (HIF-1α-dependent glucose-derived citrate) and ACC activity.

We propose that AMPK may function as a metabolic tumor suppressor, limiting the growth of cancer cells by regulating key bioenergetic and biosynthetic pathways required to support unchecked proliferation. Thus, selection against AMPK activity may represent an important regulatory step for tumor initiation and progression, allowing tumor cells to gain a metabolic growth advantage. Reduced AMPK activity has been detected in primary human breast cancer (Hadad et al., 2009), and reduced expression of prkaa2, the gene that encodes for AMPKα2, has been linked to human breast, ovarian, and gastric cancer (Hallstrom et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2012). It is also well documented that LKB1-deficiency (Shackelford and Shaw, 2009) or genetic events that target LKB1 activity (Godlewski et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2009) lead to reduced AMPK signaling in tumor cells. Thus, there may be several routes by which AMPK function is suppressed in tumors to provide a selective metabolic growth advantage.

While selection for loss of AMPK function may favor the Warburg effect in tumor cells, it may also eliminate metabolic checkpoints essential for cellular adaptation to stress. AMPK normally plays a protective role to block cell growth in response to poor nutrient conditions, and as such its loss or suppression during tumorigenesis may sensitize tumor cells to apoptosis under hypoxic or nutrient depleted environments (Svensson and Shaw, 2012). Consistent with this, silencing AMPKα1 in Eμ-Myc lymphomas conferred sensitivity to apoptosis induced by the glycolytic inhibitor 2-DG. The increased levels of ACC phosphorylation observed in Eμ-Myc tumors (Fig. 1) infer that lymphomas experience metabolic stress and AMPK activation in vivo. Thus, while ablation of AMPK signaling may enhance tumorigenesis, inhibition of this central energy-sensing pathway may offer unique a therapeutic window for the treatment of tumors with metabolic inhibitors. Our data provide a mechanistic rationale in support of the use of AMPK agonists such as metformin for cancer therapy (Buzzai et al., 2007; Evans et al., 2005), as the efficacy of these agents against tumor growth may lie in their ability to engage AMPK-dependent metabolic checkpoints to restrict anabolic growth. Understanding the reprogramming of cellular metabolic networks by AMPK in cancer may aid in the development of novel approaches for cancer therapy.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Lines, DNA Constructs, and Cell Culture

Primary mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) deficient for prkaa1 (α 1−/−) and conditional for prkaa2 (α2-fl/fl) were generated by timed mating as previously described (Jones et al., 2005), and immortalized with SV40 Large T Antigen. HCT116 cells were obtained from ATCC. Primary Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells were provided by Jerry Pelletier (Robert et al., 2009). DNA plasmids MiCD8t, pKD-HIF-1α hp, and LMP-based shRNAs against mouse and human AMPKα1 and α2 have been described previously (Bungard et al., 2010; Jones et al., 2005; Lum et al., 2007). AMPKα-deficient MEFs were generated by transducing α1−/−, α2fl/fl MEFs with Cre-expressing retrovirus to delete α2-floxed alleles. For siRNA transfections, cells were subjected to two rounds of reverse transfection with pooled siRNAs against HIF-1α (Dharmacon) using Lipofectamine RNAimax (Hatzivassiliou et al., 2005). AMPK activity was assessed in cell lines following stimulation with AICAR (1 mM, Toronto Research Chemicals) or metformin (5 mM, Sigma) for 1 hour. To induce HIF-1α protein expression, cells were treated with CoCl2 (100μM) for 1 hour. For mass isotopomer analysis, cells were incubated in glucose- or glutamine-free medium containing 10% dialyzed FBS and either uniformly labeled [13C]-glucose or [13C]-glutamine, respectively (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories).

Mice

Mice deficient for AMPKα1 (Mayer et al., 2008), floxed for AMPKα2 (Jorgensen et al., 2004), and Eμ-Myc transgenic mice (Adams et al., 1985) have been described previously. Eμ-Myc/α1−/− mice (and littermate controls) were generated by breeding AMPKα1-deficient and Eμ-Myc transgenic mouse strains. Mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions at McGill University under approved protocols.

Determination of Cell Proliferation, Competition Assays, and Cell Size

Cell proliferation curves for all cell lines was determined by cell counting using trypan blue exclusion, and a TC10 Automated Cell Counter (BioRad). For in vitro competition assays, primary Eμ-Myc lymphoma cells were transduced with retroviral vectors co-expressing GFP and AMPKα1-specific shRNA or control shRNA, and the percentage of GFP-positive cells remaining after six days of culture was determined by flow cytometry. Cell size of viable cells was quantified as the mean fluorescence intensity for FSC using flow cytometry. All flow cytometry was conducted using BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences) or Gallios (Beckman Coulter) flow cytometers and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in modified CHAPS buffer (10mM Tris-HCl, 1mM MgCl2, 1mM EGTA, 0.5mM CHAPS, 10% glycerol, 5mM NaF) or AMPK lysis buffer (MacIver et al., 2011) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Roche), DTT (1 μg/ml), and benzamidine (1 μg/ml). Cleared lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and incubated with primary antibodies. Primary antibodies to AMPK (pT172-specific and total), AMPKα2, ACC (pS79 and total), p70 S6-kinase (pT389-specific and total), S6 ribosomal protein (pS235/236-specific and total), 4E-BP1 (pT37/46-specific and total), LDHA, PDK1, Aldolase, and actin were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-HIF-1α antibodies were from Cayman Biomedical.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total mRNA was isolated from cells using Trizol and cDNA was synthesized from 100ng of total RNA using the Superscript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed using SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix (Invitrogen) and an Mx3005 qPCR machine (Agilent Technologies) using primers against aldoA, ldha, pdk1, hif1a, and actin. All samples were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. Primer sequences are listed in Table S1.

Metabolic Assays

Respirometry (oxygen consumption rate, OCR) and the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) of cells were measured using an XF24 Extracellular Flux Analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). In brief, cells were plated at 5×104/well in 625μl non-buffered DMEM containing 25mM glucose and 2mM glutamine. Cells were incubated in a CO2-free incubator at 37°C for 1 hr to allow for temperature and pH equilibration prior to loading into the XF24 apparatus. XF assays consisted of sequential mix (3 min), pause (3 min), and measurement (5 min) cycles, allowing for determination of OCR/ECAR every 10 minutes.

Glucose consumption and lactate production were determined using enzymatic assays described previously (Buzzai et al., 2007). Glucose-derived lipid biosynthesis was determined by culturing cells in medium containing 14C-glucose for 3 days, and extracted lipids using a 1:1:1 Water/Methanol/Chloroform extraction procedure (Mullen et al., 2012). Following extraction, the organic layer was isolated, dried via N2 stream, re-suspended in methanol, and incorporated radioactivity measured using a MicroBeta Liquid Scintillation Counter (Perkin Elmer).

Analysis of Metabolites by NMR and GC-MS

Metabolites from tissue culture cells were extracted as described previously (Xu et al., 2011). Briefly, cells (2 – 5 × 106/10 cm dish) were washed three times with ice cold 0.9% saline solution. Cells were lysed using ice-cold 80% methanol followed by sonication (Diagenode Bioruptor), and extracts dried by vacuum centrifugation. For NMR analysis, cell extracts were re-suspended in 220 mL 2H2O containing 0.2mM 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS), 0.1mM difluorotrimethylsilanylphosphonic acid (DFTMP), and 0.01 mM sodium azide. NMR data collection was performed at the Québec/Eastern Canada High Field NMR Facility on a 500 MHz Inova NMR system (Agilent Technologies) equipped with an HCN cryogenically cooled probe operating at 25 K. Metabolite chemical shift assignments were confirmed by total correlation spectroscopy, and targeted metabolites profiled using a 500 MHz metabolite library from Chenomx.

For GC-MS analysis, dried samples were re-suspended in 30 μL anhydrous pyridine and added to GC-MS autoinjector vials containing 70 μL N-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)-N-methyltrifluoroacetamide (MTBSTFA) derivatization reagent. The samples were incubated at 70°C for 1 hr, following which aliquots of 1 μL were injected for analysis. GC-MS data were collected on an Agilent 5975C series GC/MSD system (Agilent Technologies) operating in election ionization mode (70 eV) and selected ion monitoring. Quantified metabolites were normalized relative to protein content (μg).

Statistical Analysis

Statistics were determined using paired Student’s t test, ANOVA, or Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test using Prism software (GraphPad). Data are calculated as the mean ± SEM unless otherwise indicated. Statistical significance is represented in figures by: *, p<0.05; **, p<0.01; ***, p<0.001; ****, p<0.0001.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Loss of AMPKα1 cooperates with the Myc oncogene to accelerate lymphomagenesis

AMPKα dysfunction enhances aerobic glycolysis (Warburg effect)

Inhibiting HIF-1α reverses the metabolic effects of AMPKα loss

HIF-1α mediates the growth advantage of tumors with reduced AMPK signaling

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Connie Krawczyk, Arnim Pause, Jerry Pelletier, Francis Robert, David Shackelford, and Leah Donnelly for technical and administrative help. We are also grateful to Kimberly Wong, Alon Morantz, Valerie Laurin, and Luciana Tonelli for animal expertise. We acknowledge salary support from Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (to B.F. and R.G.J.), the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS) (to G.B. and P.M.S.), the McGill Integrated Cancer Research Training Program (MICRTP) (to B.F, G.B, and T.G.), and the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) (to F.D.). R.J.D. was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01CA157996. This work was supported by grants to R.G.J. from the CIHR (MOP-93799), Canadian Cancer Society (700586), and Terry Fox Research Foundation (TEF-116128).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, Corcoran LM, Alexander WS, Cory S, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533–538. doi: 10.1038/318533a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessi DR, Sakamoto K, Bayascas JR. LKB1-dependent signaling pathways. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006;75:137–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungard D, Fuerth BJ, Zeng PY, Faubert B, Maas NL, Viollet B, Carling D, Thompson CB, Jones RG, Berger SL. Signaling kinase AMPK activates stress-promoted transcription via histone H2B phosphorylation. Science. 2010;329:1201–1205. doi: 10.1126/science.1191241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzzai M, Jones RG, Amaravadi RK, Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Zhao F, Viollet B, Thompson CB. Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6745–6752. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo AY, Yoon SO, Kim SG, Roux PP, Blenis J. Rapamycin differentially inhibits S6Ks and 4E-BP1 to mediate cell-type-specific repression of mRNA translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17414–17419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809136105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies SP, Sim AT, Hardie DG. Location and function of three sites phosphorylated on rat acetyl-CoA carboxylase by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Eur J Biochem. 1990;187:183–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvel K, Yecies JL, Menon S, Raman P, Lipovsky AI, Souza AL, Triantafellow E, Ma Q, Gorski R, Cleaver S, et al. Activation of a metabolic gene regulatory network downstream of mTOR complex 1. Mol Cell. 2010;39:171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor R, et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331:456–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ. 2005;330:1304–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giardiello FM, Welsh SB, Hamilton SR, Offerhaus GJ, Gittelsohn AM, Booker SV, Krush AJ, Yardley JH, Luk GD. Increased risk of cancer in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1987;316:1511–1514. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198706113162404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godlewski J, Nowicki MO, Bronisz A, Nuovo G, Palatini J, De Lay M, Van Brocklyn J, Ostrowski MC, Chiocca EA, Lawler SE. MicroRNA-451 regulates LKB1/AMPK signaling and allows adaptation to metabolic stress in glioma cells. Mol Cell. 2010;37:620–632. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30:214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadad SM, Baker L, Quinlan PR, Robertson KE, Bray SE, Thomson G, Kellock D, Jordan LB, Purdie CA, Hardie DG, et al. Histological evaluation of AMPK signalling in primary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:307. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallstrom TC, Mori S, Nevins JR. An E2F1-dependent gene expression program that determines the balance between proliferation and cell death. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG. AMP-activated protein kinase: an energy sensor that regulates all aspects of cell function. Genes Dev. 2011;25:1895–1908. doi: 10.1101/gad.17420111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzivassiliou G, Zhao F, Bauer DE, Andreadis C, Shaw AN, Dhanak D, Hingorani SR, Tuveson DA, Thompson CB. ATP citrate lyase inhibition can suppress tumor cell growth. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley SA, Boudeau J, Reid JL, Mustard KJ, Udd L, Makela TP, Alessi DR, Hardie DG. Complexes between the LKB1 tumor suppressor, STRADalpha/beta and MO25alpha/beta are upstream kinases in the AMP-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol. 2003;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearle N, Schumacher V, Menko FH, Olschwang S, Boardman LA, Gille JJ, Keller JJ, Westerman AM, Scott RJ, Lim W, et al. Frequency and spectrum of cancers in the Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:3209–3215. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Wullschleger S, Shpiro N, McGuire VA, Sakamoto K, Woods YL, McBurnie W, Fleming S, Alessi DR. Important role of the LKB1-AMPK pathway in suppressing tumorigenesis in PTEN-deficient mice. Biochem J. 2008;412:211–221. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura K, Ogura T, Kishimoto A, Kaminishi M, Esumi H. Cell cycle regulation via p53 phosphorylation by a 5′-AMP activated protein kinase activator, 5-aminoimidazole- 4-carboxamide-1-beta-D-ribofuranoside, in a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:562–567. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Zhu T, Guan KL. TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell. 2003;115:577–590. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00929-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon SM, Chandel NS, Hay N. AMPK regulates NADPH homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature. 2012;485:661–665. doi: 10.1038/nature11066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RG, Plas DR, Kubek S, Buzzai M, Mu J, Xu Y, Birnbaum MJ, Thompson CB. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2005;18:283–293. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RG, Thompson CB. Tumor suppressors and cell metabolism: a recipe for cancer growth. Genes Dev. 2009;23:537–548. doi: 10.1101/gad.1756509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen SB, Viollet B, Andreelli F, Frosig C, Birk JB, Schjerling P, Vaulont S, Richter EA, Wojtaszewski JF. Knockout of the alpha2 but not alpha1 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase isoform abolishes 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-beta-4-ribofuranosidebut not contraction-induced glucose uptake in skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1070–1079. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keith B, Johnson RS, Simon MC. HIF1alpha and HIF2alpha: sibling rivalry in hypoxic tumour growth and progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JW, Tchernyshyov I, Semenza GL, Dang CV. HIF-1-mediated expression of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase: a metabolic switch required for cellular adaptation to hypoxia. Cell Metab. 2006;3:177–185. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YH, Liang H, Liu X, Lee JS, Cho JY, Cheong JH, Kim H, Li M, Downey T, Dyer MD, et al. AMPKalpha modulation in cancer progression: multilayer integrative transcriptome analysis in Asian gastric cancer. Cancer Res. 2012 doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589–3594. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine AJ, Puzio-Kuter AM. The control of the metabolic switch in cancers by oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes. Science. 2010;330:1340–1344. doi: 10.1126/science.1193494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Xu S, Mihaylova MM, Zheng B, Hou X, Jiang B, Park O, Luo Z, Lefai E, Shyy JY, et al. AMPK phosphorylates and inhibits SREBP activity to attenuate hepatic steatosis and atherosclerosis in diet-induced insulin-resistant mice. Cell Metab. 2011;13:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Cash TP, Jones RG, Keith B, Thompson CB, Simon MC. Hypoxia-induced energy stress regulates mRNA translation and cell growth. Mol Cell. 2006;21:521–531. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Ulbrich J, Muller J, Wustefeld T, Aeberhard L, Kress TR, Muthalagu N, Rycak L, Rudalska R, Moll R, et al. Deregulated MYC expression induces dependence upon AMPK-related kinase 5. Nature. 2012;483:608–612. doi: 10.1038/nature10927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum JJ, Bui T, Gruber M, Gordan JD, DeBerardinis RJ, Covello KL, Simon MC, Thompson CB. The transcription factor HIF-1alpha plays a critical role in the growth factor-dependent regulation of both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1037–1049. doi: 10.1101/gad.1529107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIver NJ, Blagih J, Saucillo DC, Tonelli L, Griss T, Rathmell JC, Jones RG. The liver kinase B1 is a central regulator of T cell development, activation, and metabolism. J Immunol. 2011;187:4187–4198. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer A, Denanglaire S, Viollet B, Leo O, Andris F. AMP-activated protein kinase regulates lymphocyte responses to metabolic stress but is largely dispensable for immune cell development and function. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:948–956. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen AR, Wheaton WW, Jin ES, Chen PH, Sullivan LB, Cheng T, Yang Y, Linehan WM, Chandel NS, DeBerardinis RJ. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature. 2012;481:385–388. doi: 10.1038/nature10642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papandreou I, Cairns RA, Fontana L, Lim AL, Denko NC. HIF-1 mediates adaptation to hypoxia by actively downregulating mitochondrial oxygen consumption. Cell Metab. 2006;3:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert F, Carrier M, Rawe S, Chen S, Lowe S, Pelletier J. Altering chemosensitivity by modulating translation elongation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5428. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenza GL. Oxygen sensing, homeostasis, and disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:537–547. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford DB, Shaw RJ. The LKB1-AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:563–575. doi: 10.1038/nrc2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackelford DB, Vasquez DS, Corbeil J, Wu S, Leblanc M, Wu CL, Vera DR, Shaw RJ. mTOR and HIF-1alpha-mediated tumor metabolism in an LKB1 mouse model of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11137–11142. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900465106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Bardeesy N, Manning BD, Lopez L, Kosmatka M, DePinho RA, Cantley LC. The LKB1 tumor suppressor negatively regulates mTOR signaling. Cancer Cell. 2004a;6:91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw RJ, Kosmatka M, Bardeesy N, Hurley RL, Witters LA, DePinho RA, Cantley LC. The tumor suppressor LKB1 kinase directly activates AMP-activated kinase and regulates apoptosis in response to energy stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004b;101:3329–3335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308061100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson RU, Shaw RJ. Cancer Metabolism: Tumour friend or foe. Nature. 2012;485:1. doi: 10.1038/485590a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu M, Neilson A, Swift AL, Moran R, Tamagnine J, Parslow D, Armistead S, Lemire K, Orrell J, Teich J, et al. Multiparameter metabolic analysis reveals a close link between attenuated mitochondrial bioenergetic function and enhanced glycolysis dependency in human tumor cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C125–136. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00247.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Vu H, Liu L, Wang TC, Schaefer WH. Metabolic profiles show specific mitochondrial toxicities in vitro in myotube cells. J Biomol NMR. 2011;49:207–219. doi: 10.1007/s10858-011-9482-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Jeong JH, Asara JM, Yuan YY, Granter SR, Chin L, Cantley LC. Oncogenic B-RAF negatively regulates the tumor suppressor LKB1 to promote melanoma cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2009;33:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N, et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.