Abstract

We report a case of an 18-year-old male who presented with watering and inability to close the left eye completely since 6 months and inability to move both eyes outward and to close the mouth since childhood. Ocular, facial, and systemic examination revealed that the patient had bilateral complete lateral rectus and bilateral incomplete medial rectus palsy, left-sided facial nerve paralysis, thickening of lower lip and inability to close the mouth, along with other common musculoskeletal abnormalities. This is a typical presentation of Moebius syndrome which is a very rare congenital neurological disorder characterized by bilateral facial and abducens nerve paralysis. This patient had bilateral incomplete medial rectus palsy which is suggestive of the presence of horizontal gaze palsy or occulomotor nerve involvement as a component of Moebius sequence.

Keywords: Bilateral medial rectus palsy, facial diplegia, Moebius sequence

Moebius syndrome is a very rare congenital neurological disorder characterized by bilateral facial and abducens nerve paralysis. Most patients usually present in infancy or early childhood although they may present late into adolescence if associated with less severe disease. Only about 300 cases have been reported in the literature and the average incidence is 0.002% with a geographic variation. The most frequent mode of presentation is facial diplegia with bilateral lateral rectus palsy, but there are variations. We report one such rare case of Moebius syndrome in an adolescent male who presented with left-sided facial and bilateral abducens nerve palsy along with bilateral moderate restriction of medial rectus muscle and other systemic musculoskeletal abnormalities.

Case Report

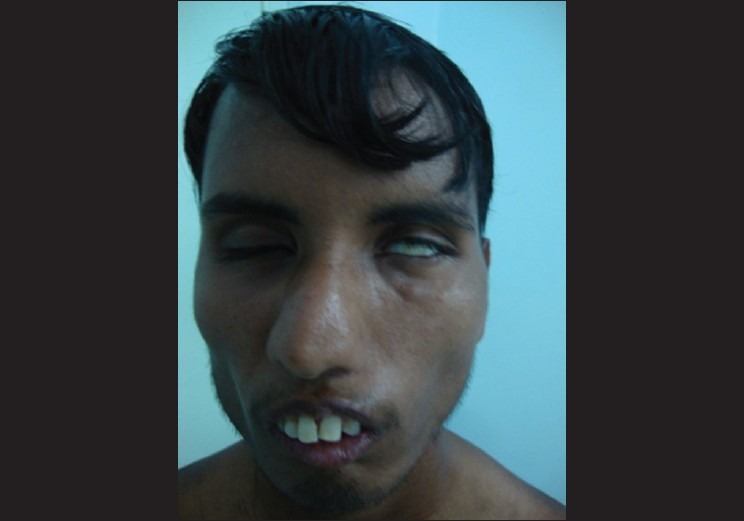

An 18-year-old male came to Mamata General Hospital in January 2010 with a history of restricted outward movements of the eyes, inability to form facial expressions and to completely close the left eye, along with associated limb deformities, and inability to completely close the mouth, present since childhood. He had additional complaints of watering along with burning and gritty sensation of the left eye since past 6 months for which he took an ophthalmic consultation.

General physical examination revealed both upper and lower limb deformities in the form of webbed fingers and poorly developed palms on the upper limbs and maldeveloped right lower limb [Figs. 1 and 2]. Facial examination revealed deviation of the nose to the right, thickened lower lip, and inability to fully approximate the lips even on forceful attempts [Fig. 3]. There was no tongue atrophy.

Figure 1.

Webbed fingers and poorly developed palms

Figure 2.

Absent right foot

Figure 3.

Thickend lower lip and nose deviation to right

On ocular examination, his best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in both eyes with +0.50 diopter sphere (Dsph). Near vision was N/6 in both eyes. The examination of visual axes revealed the eyes to be parallel with each other. There was restricted convergence and extraocular movements were totally restricted in abduction, and dextro- and levoversions showed moderate restriction of adduction [Fig. 4]. There was no diplopia at near or distance or any kind of nystagmus in any gaze. Lagophthalmos of the left eye and a positive Bell's phenomenon was present due to ipsilateral facial nerve palsy [Fig. 5] and there was loss of conjunctival luster due to exposure.

Figure 4.

Completely absent abduction and partially absent adduction in both eyes

Figure 5.

Thickened lower lip and Bell's phenomena

Rest of the anterior segment evaluation showed normal anterior chamber, briskly reacting pupils, and no opacities in the lens. Fundus examination also was within normal limits. Forced duction test performed was found to be negative. A magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the pons and adjacent brainstem was also ordered which did not show any abnormality or any nuclear hypoplasia.

The patient was managed by prescribing lubricating eye drops four times a day, and the necessity to undergo a left-side lower lid tarsorraphy and its surgical outcome was explained to him.

Discussion

The case presented here had bilateral, lateral, and medial recti involvement. Partial bilateral loss of adduction suggested III nerve palsy. Although there is textual mention about III–XII cranial nerves getting involved, never has a case of Moebius syndrome with III nerve involvement been reported previously in literature, to the best of our knowledge. The presence of a horizontal gaze palsy holds good in this case. Since there were multiple systemic associations along with the above-said ocular features, the diagnosis of a newly termed Moebius sequence was arrived at. Bilateral medial recti involvement could be a component of horizontal gaze palsy or a hypothesis for an occulomotor nerve involvement could be made. The presence of multiple ocular manifestations along with systemic involvement in a case of Moebius sequence possibly suggests multiple cranial nerve hypoplasia as the cause.

Moebius syndrome is due to a loss of function of motor cranial nerves. Although Von Graefe described a case of congenital facial diplegia in 1880, the syndrome was reviewed and defined further by Paul Julius Mobius, a German neurologist, in 1888. In 1939, Henderson broadened the definition and included cases with congenital unilateral facial palsy.[1]

Moebius syndrome results from an underdevelopment of VI and VII cranial nerves. People with Moebius syndrome are born with facial paralysis and inability to move their eyes laterally. Cranial nerves III–XII may be affected, the most common ones being V, VI, VIII, and XII. The estimated incidence of Moebius syndrome is 2–20 per million live births.[2]

The pathogenesis and etiology of Moebius sequence appear to be multifactorial and remain controversial. It is thought to result from a vascular disruption in the brain during prenatal development.[3] Many workers believed that there is hypoplasia or agenesis of the cranial nerve nuclei during fetal development. The genetic mode of inheritance is sporadic with no strong predilection. Use of drugs like misoprostol, thalidomide, and cocaine[4] during pregnancy relates to a higher incidence.

Facial diplegia is the most noticeable symptom. This may be observed soon after birth with incomplete eyelid closure during sleep, drooling, and difficulty in sucking.[5] Inability to make facial expressions and close the mouth is seen in most of the patients. Lip abnormalities like undue prominence and eversion of lower lip coexist with speech defects.

Most frequently reported associations include Kallmann syndrome[6] (hypogonadotrophic hypogonadism), Poland anomaly (hypoplasia or absence of the pectoralis major muscles), congenital bilateral vocal cord paralysis, brachial malformations, orofacial abnormalities, and hearing defects.[7] No diagnostic laboratory studies yield findings specific to Moebius sequence. Computed tomography (CT) or MRI may demonstrate cranial nerve nuclei hypoplasia or calcification and sometimes cerebral malformation.

Since the disease is congenital and nonprogressive, no definitive and established treatment has been described. Ocular care has to be taken to preserve the surface and a tarsorraphy may be advised depending upon the patient's need. Careful monitoring of the complications that might set in, patient education, and a multidisciplinary approach by health professionals help to reduce the morbidity.

In our case as well, the theory of nuclear hypoplasia appears to holds good for III, VI, and VII nerve involvement and the gaze palsy, but associated features like maldevelopment of foot and palm with webbing of fingers show that the diverse manifestations of Moebius sequence are due to some noxious agents acting on the embryo at the time of development.[8]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Henderson JL. The congenital facial diplegia syndrome: Clinical features, pathology and etiology. Brain. 1939;62:381–403. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuklík M. Poland-Möbius syndrome and disruption spectrum affecting the face and extremities a review paper and presentation of five cases. Acta Chir Plast. 2000;42:95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briegel W. Neuropsychiatric findings of Möbius sequence: A review. Clin Genet. 2006;70:91–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puvabanditsin S, Garrow E, Augustin G, Titapiwatanakul R, Kuniyoshi KM. Poland-Mobius syndrome and cocaine abuse: A relook at vascular etiology. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:285–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar D. Moebius syndrome. J Med Genet. 1990;27:122–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen SR, Thompson JW. Variants of Mobius’ syndrome and central neurologic impairment. Lindeman procedure in children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1987;96:93–100. doi: 10.1177/000348948709600122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griz S, Cabral M, Azevedo G, Ventura L. Audiologic results in patients with Moebiüs sequence. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1457–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nirankari MS, Singh D, Parkash O. Mobius syndrome. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1963;11:76–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]