Abstract

In Sen’s Capability Approach (CA) well-being can be defined as the freedom of choice to achieve the things in life which one has reason to value most for his or her personal life. Capabilities are in Sen’s vocabulary therefore the real freedoms people have or the opportunities available to them. In this paper we examine the impact of capabilities alongside choices on well-being. There is a lot of theoretical work on Sen’s capability framework but still a lack of empirical research in measuring and testing his capability model especially in a dynamic perspective. The contribution of the paper is first to test Sen’s theoretical CA approach empirically using 25 years of German and 18 years of British data. Second, to examine to what extent the capability approach can explain long-term changes in well-being and third to view the impact on subjective as well as objective well-being in two clearly distinct welfare states. Three measures of well-being are constructed: life satisfaction for subjective well-being and relative income and employment security for objective well-being. We ran random and fixed effects GLS models. The findings strongly support Sen’s capabilities framework and provide evidence on the way capabilities, choices and constraints matter for objective and subjective well-being. Capabilities pertaining to human capital, trust, altruism and risk taking, and choices to family, work-leisure, lifestyle and social behaviour show to strongly affect long-term changes in subjective and objective well-being though in a different way largely depending on the type of well-being measure used.

Keywords: Subjective and objective well-being, Happiness, Work-leisure choices, Income security, Employment security, Sen’s capability approach, German and British panel data, Fixed effects GLS models

Introduction

There is a plethora of studies on the theoretical aspect of the capability approach (CA) of Sen, but contrasting little evidence and lack of research on the measurement of capabilities especially in a dynamic perspective. The need to address empirical research on the CA is however acknowledged (see e.g. Schokkaert 2007; Stiglitz et al. 2009). In this paper we test Sen’s capability model by viewing the impact of capabilities and choices on well-being using 25 years of German and 18 years of British data. The basic idea is to test Sen’s CA framework for explaining long-term changes in objective (OWB) and subjective well-being (SWB).

Three measures of well-being are constructed: life satisfaction for SWB and relative income and employment security for OWB. The test makes use of two of the richest panel data sets in terms of breath and depth; the German panel for 1984–2008 (SOEP) and the British one for 1991–2008 (BHPS), both containing extended information on important determinants of well-being such as personality traits, human, social and cultural capital, employment status, health, life values, time use, and work-leisure and life choices. The paper builds forth on earlier attempts to explain non-transient long-term changes in well-being (Headey and Wearing 1992; Headey et al. 2010, 2011).

Outline

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the capability framework and how it can be used in empirical research to study well-being. Subsequently, in Sect. 3 the empirical model is explained while in Sect. 4 some evidence is presented on the applied well-being measures. Section 5 reports on the estimation results of the random and fixed panel regressions and in Sect. 6 we end with conclusions and some discussion on how to progress in future research.

Theoretical Framework and Conceptual Model

Well-Being: Objective or Subjective

In much of Sen’s work he views well-being as being primarily objective, whereas others, especially in the realm of psychology, adopt a subjective interpretation (Headey 1993, 2008; Headey et al. 2008; Diener and Oishi 2000; Kahneman 2003; van Praag and Ferrer-i-Carbonell 2004; Kahneman and Krueger 2006; Clark et al. 2008a, b). Sen was critical about stated or subjective measurement because disadvantaged people might report high levels of SWB partly due to ignorance or deficiencies in their knowledge of the range of choices that ought to be available to them. Another argument is related to adaptation and anticipation effects: people in their subjective assessment of the quality of their lives adapt themselves rather quickly to a new situation (e.g. a rise in income or wealth) or even anticipate to future changes and adjust their judgment and behavior accordingly suggesting that though income or resources changes affect peoples’ well-being or poverty status in the short run they do not in the longer run (Easterlin 2001; Clark et al. 2008b; Ball and Chernova 2008). Arguments in favor of the subjective interpretation concerns the claims of especially psychologists that beliefs and motivations affect behavior but also of sociologists’ that well-being is relative referring to the ‘keeping up with the Joneses’ argument; people tend to judge their own well-being relative to others by comparing their own situation with their peers’ as in social comparison and relative deprivation theory (Festinger 1954; Runciman 1966). Whereas most studies either use objective or subjective measures the joint use of these will in our view provide a better insight into the relationship between people’s capabilities and their choices or behavior (cf. Oswald and Wu 2010). The literature on the subject further shows that the concepts of well-being such as happiness, life satisfaction, psychological stress, affect or subjective welfare are interchangeably used even though they measure dissimilar concepts. Common to all approaches however is that a distinction is made between objective and subjective measures of well-being (Schokkaert 2007).

Sen’s Notions of Capabilities and Functionings

According to Sen, well-being can be defined as the freedom of choice to achieve the things in life which one has reason to value most for his or her personal life. In Sen’s vocabulary the freedoms are the capabilities to achieve particular functionings (the doings and beings) such as finding a partner, getting a job or following education. Capabilities are the real freedom people have or the opportunities and choices available to them. Central is ‘freedom of choice’: people, in Sen’s view, should have the opportunities to achieve the functionings they have reason to value most for their personal lives (Sen 1983, 1993, 1999a, b, 2004, 2005; Muffels et al. 2002; Alkire 2007; Nussbaum 1997). The choices people make during their life are dependent on their capabilities which impact their well-being outcomes. However, the societal and economic context imposes constraints on the choices and hence on the well-being outcomes. These constraints refer to income or liquidity and employment and health constraints holding people back on their preferred choices.

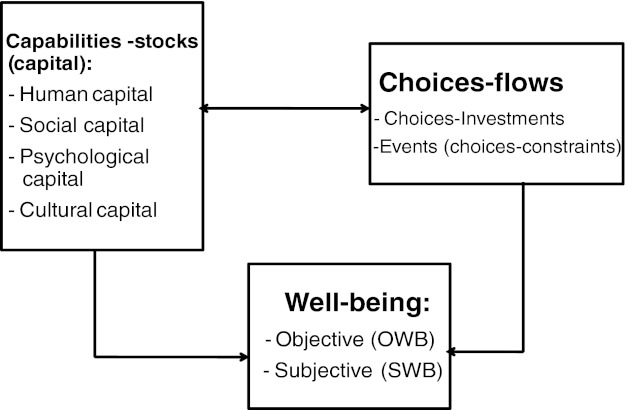

Direct empirical measures for peoples’ capabilities viewed as the ability to achieve certain functionings are obviously very difficult to define. The approach in this paper is therefore to define indirect measures based on empirical data. The capability framework translates in our approach into a ‘capabilities-choices-events’ (CACHE) model. From a dynamic perspective we might argue that capabilities and choices pertain to stocks and flows respectively. Within the life satisfaction literature there is—to our knowledge—little to no empirical work done testing Sen’s framework in this way. Previous studies viewed the role of life values (Headey 2008) and events such as divorce and job loss or recurrent unemployment (Winkelmann and Winkelmann 1995; Clark et al. 2008a). Others also looked into the role of particular choices, such as the choice of a partner or children (Diener et al. 1999; Powdthavee 2007; Cuven et al. 2010). No study to our knowledge attempts to bring the various components of Sen’s model together.

A Capability-Choice-Events Approach

The capabilities or stocks are indicated by the amount of economic, social, cultural and psychological capital people possess:

Economic capital pertaining to wealth, human capital endowments and skills (Becker 1975)

Social capital (Putnam 2000, 2005) pertaining to the level of trust in other people and the social networks people are involved in, indicated by the frequency of contact with others and the support people get from others in their network (bonding social capital), but also the membership of organizations and associations or clubs such as trade unions, social and sport clubs (bridging social capital)

Cultural capital pertaining to individual values and life goals, such as work, family and social values like helping others and volunteering, but also life goals such as forming a family, raising children or making a career and to risk attitudes such as risk taking or risk aversion (Dohmen et al. 2011)

Psychological capital pertaining to people’s personality traits, generally indicated by the so-called ‘big five’: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness to experience (e.g. Diener et al. 1999).

These forms of capital impact on peoples’ life chances and opportunities although the returns in terms of happiness depend on peoples’ efforts and choices or their doings and beings. The doings are the efforts or choices themselves, such as caring or volunteering, or the decision to invest in the career through training, job search, exercising etc. Peoples’ efforts and choices are however not necessarily voluntary. People might have to make involuntary choices due to constraints associated with the occurrence of events such as dismissal, divorce, disability, death of the partner or a child etc. The inclusion of events makes the capability model ‘path-dependent’ since the sort of events people experience over time and how long they lasts, tend to affect their well-being. The life satisfaction literature suggests that though most events only have temporary effects the adverse effect of particular events like disability, the death of a child, job displacement, or recurrent unemployment on life satisfaction might persist rather long (cf. Clark et al. 2008b).

Capabilities and Choices

Human capital can be seen as a capability affecting people’s well-being over time. Further education and training is an investment in human capital and the career, just like overtime work. Health is a capability because it is partly determined by people’s genetic heritage and partly the return to an investment in a healthy or unhealthy life style irrespective of people’s genetics. Exercising, sport activities and smoking and drinking are choices or investments in one’s health. Trust in other people is a capability while it induces cooperation that pays-off in returns and social support. The time invested in meeting other people can be seen as a choice to invest in social capital. The frequency of social contacts and whether people get support from their friends or neighbors, another dimension of social capital, indicate the capability of people to build up a social network. Risk attitudes, but also life goals can be seen as capabilities being part of people’s cultural capital just as religion or religious denomination is. In the literature it is shown that life goals matter for SWB (Headey 2008). These life goals can be divided into economic (success in job, affording luxuries, owning a house etc.), family (importance of having children or a partner), and social goals (altruism, get support from neighbors, good relationships with friends).1 According to Headey (2008) economic life goals represent zero sum and family and social life goals positive sum domains. In zero sum domains gains for one always imply losses for others whereas in positive sum domains, gains are either not at the costs of others or even improve those of others. The time spent in volunteering and caring is an investment in cultural capital. Another component of cultural capital pertains to risk attitudes in the form of risk-seeking or risk-averse behavior while they influence people’s achievements and outcomes.

Events

Events are voluntary or involuntary choices (constraints) affecting future outcomes. Divorce can be seen as an event following a decision to split with large consequences for people’s well-being. But also marriage tends to have long-term consequences just like unemployment or stopping a business. There is ample evidence in the literature on the positive effects of marriage and the negative effects of divorce and unemployment on SWB (Gangl 2006; Headey 2008; Clark et al. 2008a; Headey et al. 2010). The two panel surveys now permit to define a variety of events, like moving into poverty, job displacement, early retirement, divorce, marriage etc.2

The ‘Capabilities-Choices-Events’ (CACHE) Model

The model is presented in Fig. 1. Well-being is the outcome of the interaction process between capabilities and choices. Using panel data we can associate levels of and changes in capabilities to particular choices by viewing the sequence of changes in capabilities and choices over time. However, some reverse causation between capabilities and choices might exist. People might adapt and change for example their life goals in the next period when the desired choice cannot be realized due to constraints.

Fig. 1.

A ‘capabilities-choices-events’ (CACHE) model of well-being based on Sen’s capability approach

The Empirical Model

The capability model is aimed at explaining objective and subjective well-being over time but leaves the question into the relationship of SWB and OWB aside. Though this relationship is interesting for further scrutiny it is not the main purpose of the paper, that is, to view the separate impact of capabilities and choices on various measures of well-being used in the literature. In Sect. 4, we show that the concepts of OWB and SWB are clearly associated but that the correlations are all below 0.35 indicating that they pertain to different concepts. We therefore expect that some of the correlates of SWB (such as personality traits) will have low correlations with OWB and vice versa, that particular correlates of OWB (such as human capital endowments) have low correlations with SWB.

Country and Welfare Regime

We use evidence for two countries to test Sen’s approach in two rather different welfare states.3 For interpretation of the differences across the two countries we make use of the Varieties of Capitalism (VOC) literature (Hall and Soskice 2001). According to the VOC literature the two countries represent two different types of market economies: a strongly coordinated (Germany) and a weakly coordinated, more or less liberal type (United Kingdom). The question addressed is to what extent Sen’s CA model is able to explain well-being in these two countries representing two different market economies. The distinction is relevant for Sen’s framework because people’s ‘capabilities’ are to a large extent influenced by the level of their human capital obtained through education, learning on the job and training. The coordinated type is now typified by a so-called ‘specific skills’ regime and the weakly coordinated one by a ‘general skills’ regime (see also Estéves-Abe et al. 2001). We therefore suspect that a ‘specific skills’ regime due to the non-transferability of these skills to other employers meet particularly problems to ensure employment security for particularly the low-skilled whereas a ‘general skills’ regime due to the way markets work might encounter problems to ensure low-skilled workers income security or income stability over the career. The British education system is suspected to have ‘meritocratic’ features because of which the low educated might have more chances to make a career and move upwards on the career ladder attaining higher wage levels than the low educated in Germany who have worse chances to escape a low level job or to improve their career.

Data and Methodology

Data

We used the German and the British panel covering respectively 25 (1984–2008) and 18 years (1991–2008) of data. We included all persons of 16–65 years. All incomes were deflated by the consumer price index. The data were weighted with the product of the cross-sectional weights and the staying factors (the probability to stay in the panel across two consecutive waves). We created a person-year file while including information from the monthly calendars for the entire period.

The information on risk attitudes and life values were collected in only four years (SOEP) of the German panel. The UK data do not contain information on risk attitudes and in only three waves information was asked about social values, the last time in 2008. Though values might change over time they turn out to be rather stable across the 3 and 4 years of observation in the British and German panel. We therefore imputed the values for the missing years in between by taking the average of the values between 2 years if available for that particular person. We also used the information on time use which was available for many years in the German and some years in the British panel. Even though time use information reflect preferences as well as behavior and therefore tend to change more over time than just values, for avoiding losing too many observations we imputed the values for the missing years by calculating the average of the values for the two non-missing years which are closest to the missing year.

Three Measures for Objective and Subjective Well-Being

In this paper we use objective and subjective measures of well-being indicated by three yardsticks: income and employment security and life satisfaction:

Income security is defined as escaping relative low income statuses. We calculated the ratio of each person’s equivalent household income in proportion to the 60% income poverty threshold as used by the OECD and Eurostat. The income measure is a rather well-known continuous measure of ‘relative income’ very similar to Sen’s well-know ‘income inequality’ or ‘income deprivation’ measure though his inequality measure was defined as a weighted gap between income and the income threshold (weighted with the level of inequality among the poor) instead of the ratio. The income information in both panels refers to the last year’s income period but in Germany this is the last calendar year whereas for the UK it is the current year running from the last interview in the period October-December last year to the same interview period this year. For Germany we therefore assigned the t + 1 income to the current year whereas for Britain we used the information as it is given for the current year.

Employment security is defined as the number of weeks people were full-time or part-time employed in the current year. Since the information in both panels is asked for the preceding year we assigned the values of the next year to the current year. People might however choose for part-time employment because they cannot find a full-time job. But when people prefer to work part-time and they are able to realize their preferences they should be considered as being employment-secure. For that reason we correct for whether the part-time or full-time work corresponds to people’s working time preferences or not. We correct for the voluntary nature of a low attachment to the labor market by deriving a variable indicating whether people want a job or prefer not to work. Unemployed and inactive people in the British as well as the German panel were asked whether they actively search for a job or not and whether they are available for work and can start in due course. In the second step we used this information to define a job or hours match variable indicating whether the actual working hours match peoples working time preferences or not. In the latter case they are overworked (work more hours than they want) or underworked (work less hours). Unemployed and inactive people are assumed to be underworked if they actively look for a job, otherwise they are classified as having their preferences met.

Life satisfaction is measured in the usual way on a scale of 0–10 as in Germany or 1–7 as in the UK, 0 indicating the lowest level and 10 or 7 the highest. The life satisfaction question is asked every single year in the German panel but only as of 1996 in the British panel and missing for 2001, so for 11 years only. We transformed the British scale into a 0–10 scale. According to set-point theory (Diener and Oishi 2000; Headey 1993; Headey et al. 2010) people’s life satisfaction score remains rather stable over time because each individual tend to stay on his or her own track, dependent in particular on a person’s score on the ‘big five’ social-psychological traits. Shocks associated with health impairments or life events (such as unemployment, marriage/divorce) may cause people to depart from their long-term path but only temporarily; people tend to recover rather quickly to return to their quasi permanent baseline track.

The Empirical Model

We employed random and fixed effects panel regression models to allow correcting for unobserved heterogeneity or individual effects. This is important because capabilities are unobserved factors which are likely to be associated with the observed measures for capabilities that we included in our models such as education level and participation in training. Even though we were able to incorporate many capability and choices indicators we cannot rule out the possibility that we only partly capture the unobserved heterogeneity related to factors as ability, motivation and effort. The fixed effects (FE) models correct for this provided that these unobserved factors are assumed to be time constant. The FE models show the impact of changes in the covariates such as capabilities, choices and events on changes in well-being since the model takes the difference of the dependent and independent variables with the means over time. The random effects (RE) models show the impact of time constant but important factors such as gender, education level and being an immigrant etcetera on measures of SWB and OWB which are removed in the fixed-effects models. More importantly, the random effects models show the relative size of the effects of personality traits (measured only once) compared to those of capabilities, choices and events. For these reasons we estimated random and fixed effects panel regression models separately for the three measures of subjective well-being (SWB), income security (YS) and employment security (ES):

|

1 |

|

2 |

|

3 |

where income security (YS

it) is the ratio of equivalent income of each individual at time t to the level of the poverty line (pl

t) in the country for year t as defined by the 60% of the median household income threshold ( ). Employment security is defined as the number of weeks employed in the current year (Empl

w) and life satisfaction or subjective well-being (SWB) as the score on the life satisfaction scale in the current year ranging from 0 to 10. The X

it’s represent a set of control variables either time invariant like sex, living in East Germany and ‘born in a foreign country’ or time varying, like age, age squared, education level, number of children, life course stage and whether people are seeking work or not. The traits, capabilities and events variables are also included either as time invariant variables, like personal traits or risk attitudes (part of capabilities), or as time varying such as choices and events. The γt represents a time-specific effect that is assumed to correct for business cycle influences indicated by the yearly changing unemployment rate for each of the periods (1980s, 1990s or 2000s). The u

i represent the unobserved heterogeneity or individual effects and the disturbance is given by εit. The SWB scale is ordinal and ranges from 0 to 10.4 However, a cardinal treatment of it renders more or less the same results (Diener et al. 1999; Clark et al. 2008a). The advantage of treating the life-satisfaction scale in a linear manner is that we can correct for unobserved individual effects estimating GLS random and fixed effects models.

). Employment security is defined as the number of weeks employed in the current year (Empl

w) and life satisfaction or subjective well-being (SWB) as the score on the life satisfaction scale in the current year ranging from 0 to 10. The X

it’s represent a set of control variables either time invariant like sex, living in East Germany and ‘born in a foreign country’ or time varying, like age, age squared, education level, number of children, life course stage and whether people are seeking work or not. The traits, capabilities and events variables are also included either as time invariant variables, like personal traits or risk attitudes (part of capabilities), or as time varying such as choices and events. The γt represents a time-specific effect that is assumed to correct for business cycle influences indicated by the yearly changing unemployment rate for each of the periods (1980s, 1990s or 2000s). The u

i represent the unobserved heterogeneity or individual effects and the disturbance is given by εit. The SWB scale is ordinal and ranges from 0 to 10.4 However, a cardinal treatment of it renders more or less the same results (Diener et al. 1999; Clark et al. 2008a). The advantage of treating the life-satisfaction scale in a linear manner is that we can correct for unobserved individual effects estimating GLS random and fixed effects models.

Variables

The most important variables are of course the variables indicating the capabilities, choices and events. Table 2 shows the definition of the included variables in the model. We, firstly, added some obvious controls knowing to be important correlates of well-being such as gender, age, age squared and immigrant status. For Germany we added a variable indicating whether they are living in former East-Germany since well-being levels are known to be lower in the former East. We added as control also a life-course oriented household type variable indicating the marital status and life-stages of people (single, single parent family with young children, couple with young children, empty nest etc.). We included as indicators for capabilities measures for genetic or psychological capital, human capital and social and cultural capital. Genetic capital is measured through the ‘Big Five’ personality traits. Human capital is measured through highest attained education level and training efforts. For Germany as well as Britain we used the international education level classification called ISCED to distinguish between three levels of education (high, intermediate and low). Social capital is measured through the frequency of contacts with friends and relatives, the support they get from others in their social network and through the level of ‘trust in other people’. The amount of cultural capital is measured by the so-called life goals dealing in Germany with the importance of certain aspects in life such as altruism, success in job, what people can afford, being happy with the partner, having children, friends, travel and social or political activities and owning a house. The life goals list in the British panel largely pertains to the same items such as the importance of partner and children, of friends, owning a house, having success in work and good health. We employed for both countries a principal components factor analysis on these life goals and the results (not given here) show that there remain basically three main factors in Germany and two factors in Britain which we called the economic (in Germany success in job and to afford things, and in Britain: success in job, to afford things and living an independent life), family (importance of partner and children) and social life goals (in Germany and in Britain importance of friends). Because of the low loadings in Germany of ‘owning a house’ and ‘travel’ and ‘participation in social and political activities’ we removed these items. We did not weigh the factors with the factor loadings but just took the aggregated scores on the variables belonging to the two dimensions. Eventually we included a number of events as listed in Table 1. For Germany and Britain we constructed a limited set of events based on the monthly and/or annual information in the panel with a view to employment and marital status. These events are getting divorced, getting married or cohabiting, early retirement, start or stop one’s own business and an involuntary job change due to dismissal, being laid-off or a business close down. The constructed well-being indicators for income security (YS) and employment security (ES) and subjective well-being (SWB) refer to the current year whereas the events refer to the change from the last calendar or last financial year to the current year.

Table 2.

List of variables used in the empirical model

| Variable | Germany | Britain |

|---|---|---|

| Controls | ||

| Age and age squared | Based on year and month of birth | Based on year of birth |

| Household type (life course stages) | Couple youngest child <5 years; couple youngest child between 6 and 15, single with children, single parent, youngest child <5, single parent, youngest child between 6 and 16, other type | Similar |

| Number of children | In-living child between 0 and 16 years of age | Similar |

| Number of other employed in the household | All other members in the household with self-reported employment status | Similar |

| East-Germany and Immigrant | Living in East-Germany; not born in Germany | No region indicator used; not born in Britain |

| Interaction unemployment rate and period correcting for the business cycle | Overall annual unemployment rate is derived from the Eurostat database. Period is split into the 1980s, the 1990s and the 2000s | Similar to Germany though period split in two (1990s and 2000s) |

| Stocks | ||

| Health limitations | People reporting being handicapped or not and their degree of disability. If more than 50% people are considered disabled for work | Health problems limit amount and type of work |

| Human capital | Education level using ISCED codes and recoded into low, intermediate and high | Similar ISCED classification used |

| Social capital |

Bonding: Frequency of contacts relatives/friends, Trust other people (4 categories from totally agree to totally disagree) Bridging: Membership trade union/association, clubs |

Frequency contacts friends. Trust based on question whether people can be trusted, that runs from 1 ‘most people can be trusted’ to 3 ‘depends’ |

| Cultural capital |

Religion: Catholic, Protestant, Other Christian, Other religion, No denomination Life goals: importance of being able to afford something, altruism, success in job, family, friends, partner, owned house Willingness to take risks (11 points scale) |

Similar Life goals: importance of family, friends, success in work, health, house, travel No information on willingness to take risks |

| Functionings/events | ||

| Career choices through investing in training, apprenticeship | Training participation for the employed and unemployed separately and apprenticeship | Participation in general and specific training and apprenticeship for the employed, and in government training for the unemployed/inactive |

| Work-leisure choices indicated by job match for unemployed and employed separately | Difference between preferred and actual total working hours in all jobs smaller or equal to 3 h. More than 3 h difference indicates being overworked or underworked. Unemployed and inactive people are considered underworked when they actively search for a job | Asked to people whether they want to work more or fewer hours or that they want to continue with the same number of hours. Unemployed and inactive people are considered underworked when they actively look for a job |

| Lifestyle choices through investment in healthy lifestyle (time use) | Healthy life: active sports, exercising | Similar |

| Social choices through investment in social networks (time use) | Time spent with friends, attending community and social events, volunteer work. Time weekdays on: housework, shopping, work, visiting friends | Frequency of attending social and community events; frequency of volunteer work and of spending time with relatives/friends |

| Cultural choices through investment in culture |

Time spent on cultural events Visiting church or religious events |

Similar |

| Events such as divorce/separation, marriage/cohabitation, early retirement, involuntary job change | Constructed from the monthly calendar and from annual information at t − 1 and at interview date | Constructed from monthly information on activities and from annual information at t − 1 and t |

Source: GSOEP, 2001–2008, BHPS, 2001–2008

Table 1.

Measuring capabilities (stocks) and choices (flows)

| Capabilities-stocks | Choices-flows | Events-flows (choices-constraints) |

|---|---|---|

| Human capital | ||

| Education level | Training, following courses | Completing education, school drop out |

| Health status | Exercise, healthy life-style (smoking, drinking) | Accident, work disability, handicapped |

| Visit doctor | ||

| Job quality, wage | Job search | Lay-off, dismissal, new job, poverty |

| Working time, job preferences | (In)voluntary job change, job loss | |

| Wage expectations | Start-up, stop business | |

| Social capital | ||

| Social relationships (bonding) | Social contacts, get support | Change of residence |

| Membership union etc. (bridging) | Time spent to memberships, union, clubs | Change of residence |

| Living in a sustainable consensual union | Caring time | Marriage, cohabitation divorce, separation |

| Trust in other people | Time spent on community events, working together etc. | Revealed distrust Victim of crime |

| Cultural capital | ||

| Willingness to take risks | Invest in new job/self-employment | Change of job, business, career |

| Life goals/values | Volunteer work, social activities | Social events, life events: child birth |

| Religion |

Forming a family, number of children Attending religious events |

Personal events |

| Psychological capital | ||

| The big five (openness, agreeableness, extroversion, emotional stability, conscientiousness) | Investment in one-self (self-development) | Personal events |

Source: GSOEP, 2001–2008, BHPS, 2001–2008

First Evidence on the Three Well-Being Measures

In Table 3 some evidence is presented on the levels of our three well-being measures: subjective well-being (SWB), income security (YS) and employment security (ES) by employment status for the years 1999–2008 in Germany and Britain.

Table 3.

Three well-being measures by employment status and gender, GSOEP 1999–2008; BHPS 1999–2008

| Employment status | Germany | Britain | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWB | YS | ES | SWB | YS | ES | |

| Males | ||||||

| Employed | 7.1 | 2.1 | 49.4 | 7.0 | 2.6 | 49.9 |

| Self-employed | 7.0 | 3.0 | 50.3 | 7.1 | 2.4 | 50.9 |

| Unemployed | 5.5 | 1.2 | 7.9 | 6.1 | 1.4 | 14.8 |

| Inactive | 6.9 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 8.1 |

| Total men | 7.0 | 2.0 | 39.3 | 6.9 | 2.4 | 41.0 |

| Females | ||||||

| Employed | 7.1 | 2.2 | 47.3 | 7.0 | 2.5 | 49.1 |

| Self-employed | 7.2 | 2.8 | 46.9 | 7.0 | 2.6 | 49.9 |

| Unemployed | 5.9 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 1.6 | 17.4 |

| Inactive | 7.1 | 1.7 | 2.2 | 6.8 | 1.6 | 7.7 |

| Total women | 7.0 | 2.0 | 29.9 | 6.9 | 2.2 | 34.4 |

LS life satisfaction (0–10), YS income security (income-to-needs ratio), ES employment security (number of weeks employed in the current year)

Source: GSOEP, 2001–2008, BHPS, 2001–2008

Not surprisingly, the unemployed together with the inactive people show the lowest levels of well-being according to all measures in both countries. The average employment security level indicated by the number of weeks the unemployed still work in each year of the 10 year period is higher in Britain than in Germany. Also the female income and employment security levels are higher in Britain than in Germany whereas SWB levels are rather similar. The figures are weighted but we cannot rule out that part of the differences must be attributed to survey design differences. The three concepts seem to measure rather different concepts as also the correlations presented in Table 4 show. SWB and OWB measures are clearly associated but the correlations are all below 0.35.

Table 4.

Correlations between subjective and objective well-being measures

| Britain 1996–2008 (BHPS) | Germany 1984–2008 (GSOEP) | |

|---|---|---|

| SWB with YS | 0.10 | 0.17 |

| SWB with ES | 0.11 | 0.10 |

| YS with ES | 0.31 | 0.25 |

Source: GSOEP, 2001–2008, BHPS, 2001–2008

SWB subjective well-being, YS income security, ES employment security

When estimating a fixed-effects panel regression model on SWB (see also Sect. 5) with the standard controls (such as age, marital status, number of kids, gender, immigrant status and unemployment rate) and with the OWB measures of income and employment security as covariates, the effects of OWB on SWB turn out to be significant but rather moderate (0.11 for income security and 0.03 for employment security in Germany and 0.02 and 0.03 respectively in Britain).

Results on the Model Estimations

In the next step several GLS panel regression models are estimated to test the empirical ‘capabilities-choices-events’ model. The results show the separate contribution of capabilities, choices and events on the three measures of objective and subjective well-being. We estimated five separate models on each of the three well-being indicators. These are the following:

Model I. The baseline model with the usual controls (age, age squared, sex, household type, number of children, region (West and East German region only), being an immigrant and unemployment rate.

Model II. The traits model with the controls and the five personality traits variables included

Model III. The capabilities model with the controls and the capabilities but without the personality traits.

Model IV. The traits-capabilities model with the controls, the capabilities and the traits included

Model V. The capabilities-choices model with the controls, traits, capabilities, choices and events.

For each of the three well-being indicators five random effects models are estimated to examine the added value of traits, capabilities, choices and events for explaining well-being. The results show the effect sizes of the various measures of capabilities, choices and events and their additional explanatory power for subjective and objective well-being. Table 5 reports on the fit indices (R-squares) for the five random effects models. Random instead of fixed effects models were estimated since we had information on personality traits in the German and British panel for 1 year only. In the fixed-effects model time-constant traits variables drop out. Set-point theorists argue that subjective well-being is relatively stable over time because of the stability of personality traits not changing much after childhood. There is one exception though known from the literature associated with the death of a child which event however is relatively rare. For that reason we assumed the traits to be time-constant and imputed them for the missing years.

Table 5.

Contribution of traits, capabilities, choices and events to explaining well-being according to five random effects GLS models in Germany and Britain (R-squares)

| Germany 1984–2008 (GSOEP) | Britain 1991–2008 (BHPS)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MI | MII | MIII | MIV | MV | MI | MII | MIII | MIV | MV | |

| BL | TR | CA | TR + CA | CA + CH | BL | TR | CA | TR + CA | CA + CH | |

| Life satisfaction (SWB) | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.20 |

| Income security | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.33 |

| Employment security | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.45 |

Source: GSOEP, 1984–2008; BHPS, 1991–2008

MI–MV model I to model V, BL baseline, TR traits, CA capabilities, CH choices and events

aLife satisfaction is asked from 1996 on in the BHPS

The stocks, measuring capabilities, seem particularly important for explaining income and employment security. Adding the stocks variables to the models with only controls (model III) raises the explanatory power indicated by the R-square strongly in both countries (in Britain from 21 and 18% for respectively the income and employment security model to 29 and 28%). The traits seem particularly important for explaining life satisfaction or SWB in both countries (the R-square raises from 5 to 10% in Germany) but exert hardly any additional effect on explaining income and employment security. Comparing models II, III and IV on SWB shows that the joint impact of stocks and traits is larger than the impact of each separately, though without being additive. Favorable traits seem to reinforce people’s capabilities and jointly determine more than each separately changes in subjective well-being. The effects of choices and events are particularly strong in the employment security model in both countries and to a lesser extent also in the income security model. As will be shown later, in particular work-leisure choices exert a strong impact on changes in income and employment security over time. On the other hand social choices turn out to be more important for SWB than for OWB whereas the effect of the work-leisure choice is smaller in the SWB models especially in Britain, though the impact is still substantial.

Fixed Effects (FE) Models

Since we are also interested in the effects sizes of the various capabilities and choices separately for the three well-being measures we estimated in the second stage fixed effects models in particular the extended Model V, the model with capabilities, choices and events. We employed the Hausman model selection test, showing indeed that the fixed effects model should be preferred over the random effects in both countries for all three well-being measures. The FE specification is the preferred one because the individual unobserved effects are likely to be associated with especially our capability measures. The results are given in Table 5 (Germany) and 6 (Britain) in “Appendix”.

Below we discuss shortly the outcomes showing to what extent capabilities and choices can explain long-term changes in objective and subjective well-being.

Results from the Random and Fixed Effects Models in Germany and Britain (Estimation Results are Given in “Appendix”)

We briefly review the results of the baseline model for the well-being measures since the results confirm the evidence in the literature. The relationship of SWB with age is U-shaped, first decreasing up to 45 years in Germany and 41 in Britain and then increasing. But for income and employment security the relationship is exactly the opposite, inversely U-shaped, first for income security increasing up to 50 years in Germany and 42 years in Britain and for employment security up to 39 years in both countries and then decreasing. It shows that subjective and objective well-being measures are indeed different concepts which need to be studied separately.

Children tend to increase life satisfaction in Germany but to reduce it in Britain which is remarkable. On the other hand, children seem to reduce people’s income security and especially employment security in both countries compared to people without children. This is known in demographic research known as the ‘life cycle squeeze’ associated with the retreat of the female partner from the labour market after childbirth resulting in a decline of income (see e.g. Kalmijn and Alessie 2008), the so-called ‘child valley’ in life cycle income. Nevertheless, couples with very young children are happier than couples without children but only in Germany; in Britain they are seemingly less happy. Worst off though are single parent households with young children viewing their levels of subjective and objective well-being in both countries. This confirms the ‘income squeeze’ thesis since these households suffer most from a reduced household income due to a combination of labour market withdrawal and the income consequences of divorce while facing increasing costs of children. The ‘child valley’ effect seems therefore more important for these single parent families. The more household members work the happier people are in Germany but not in Britain. The latter finding might be associated with ‘time squeeze’ effects because of the reduced time left for fulfilling caring duties and household chores. The more workers there are in the household the better though the level of income and employment security in both countries. East-Germans and immigrants share a lower level of subjective well-being and have a worse record in maintaining income and employment security. The British immigrants fare apparently better with a view to their subjective well-being than their German counterparts. The unemployment evidence confirms the adverse impact of unemployment experience known from the literature on subjective and objective well-being in Germany as well as in Britain.

The fixed effects results are very similar to the random effects results except for the unemployment rate that becomes insignificant in the FE model. That effect seems to be taken over by the effect of the number of workers in the household which effects is stronger in the FE model.

Traits

The purpose of the analyses is to show the effects of capabilities after netting out the effects of personality traits. The evidence on traits, as being part of the set of capabilities, confirms the adverse effects of emotional instability or neuroticism on life satisfaction in both countries. All the other personality traits except openness show a positive effect on subjective well-being in both countries. Less well-known are the significant effects of these traits on income and employment security. Especially the sign and the size of the negative effects of neuroticism and of openness and agreeableness on employment security in Germany are remarkable. In Germany but also in Britain we find a negative effect of agreeableness on income and employment security. Conscientious people seem more satisfied with life though they are less income secure and more employment secure in Germany. In Britain they are both, more income and employment secure.

Capabilities

The more human, social and cultural capital endowments people have the more satisfied they are with life and the better they appear capable of maintaining one’s income and employment security in both countries. A high education level warrants a job and therefore pays off in terms of feeling happier. Remarkably though, the effect of education level on SWB is negative in Britain according to the random effects model possibly reflecting the meritocratic nature of the British system. In particular the adverse effect of health limitations and disability shows up very strongly in all models in both countries.

Interestingly, we find significant effects of the ‘willingness to take risks’ variable in Germany showing that economic risk seeking behavior seems to reward in terms of life satisfaction and staying income and employment secure at least in the random effects models. In the fixed effects models the impact on income and employment security turns insignificant and even negative. This is likely to be due to the few measurements we had and the lack of variation associated with that. Another interesting finding deals with the positive impact of social capital (trust, memberships). It is shown that ‘trust in other people’ exerts a particularly strong positive effect on subjective well/being in Germany as well as in Britain. The positive effect of trust on income and employment security in both countries disappears in the fixed effect model. This might again be due to the few measurement time-points and lack of variation over time. The impact of social capital on income and employment security is especially in Britain also reflected in the strong positive effect of membership of a trade union or association. Both results render firm support to the social capital thesis put forward by Putnam and others (Putnam 2000; Putnam et al. 2005).

Religion exerts a small effect on income and employment security but a stronger effect on life satisfaction in both countries. In Britain, Protestants and Other Christians are slightly happier compared to Catholics, whereas in Germany people with no denomination or another religion are less happy. Social and family life goals make people feel happier in Germany and in Britain but not necessarily more income and employment secure. The positive effects on SWB are rather strong in both countries (Muffels and Kemperman 2011; Headey et al. 2011). On the other hand, the more important social goals are, the less employment secure people tend to be, both in Germany and Britain. The explanation might be that the time invested in family and social networks make people happier but reduces the time available for working. That family and social goals do not harm people’s income security—in Germany family goals even have a positive effect on income security—might be related to the positive impact of social capital on the job match and the career counterbalancing the negative time spending effect. The SWB literature suggests that persistent rather than transient commitments to material goals matter more for life satisfaction (see Headey 2008; Headey et al. 2010). The random effects models show no effect of material goals on SWB in Britain and in Germany. In an earlier paper on Germany we found support for the findings in the literature that persistent commitment to material life goals not only matter more to happiness than short-term commitments but also that they exert a negative effect on SWB too. The negative effect is confirmed in another paper on the German, British and Australian panel data (Muffels and Kemperman 2011; Headey et al. 2011). The explanation might be that striving for material success may make people happier in the short-term but harms people social relationships in the longer-term while it reduces the time spent with friends and relatives.

Choices

Working overtime turns out to be rewarding while it indeed improves people’s income and employment security in Germany and Britain. It has no effect on people’s life satisfaction in Britain and only a small positive effect on their SWB in Germany which is slightly surprising. The effects of being overworked or underworked while at work on subjective well-being are much stronger though in both countries suggesting that it is not the number of hours that matters but to what extent people’s working hours fit or match their working time preferences. In another paper (Muffels and Kemperman 2011; Headey et al. 2011) focusing on German women of 20–55 years we find strong support for the impact of the hours match on subjective well-being. Employed people working less than they wish (underworked) pay a price in terms of income security in both countries but their employment security is even improved compared to working and non-working people for which the working hours match their preferences. On the other hand overworked people (working more than they wish) are less happy but more income and employment secure. The negative effects of being over or underworked on SWB are rather strong. They are even stronger for the unemployed and inactive people, which is not surprising with a view to the stronger mismatch between their preferences and actual involvement in work.

For training we find rather strong and positive effects on well-being in Britain but puzzling negative effects on all well-being measures in Germany. The reason might be that it resembles the adverse well-being outcomes for the unemployed or inactive people who participate strongly in (vocational) training in Germany. For the same reason we also find negative effects for apprenticeship jobs in Germany. The explanation might also be found in the different professional education system and the earlier discussed difference between a ‘general skills’ regime such as in Britain and a ‘specific skills’ regime such as in Germany. In Germany potential workers are educated and trained in the highly stratified vocational (apprenticeship) education system for a particular job in a particular profession with specific skills prior to entering the labour market. Formal training on the job can therefore be limited to compensate for lack of skills obtained before. In Britain the educational system is much less stratified with respect to vocational education and it provides much larger shares of (lower educated) workers with general skills who require training on the job to fulfill a specific job (Korpi et al. 2003). Training tends to act as a sorting mechanism to select workers into the better jobs and careers. These results on training require further scrutiny with a different research design since for examining the effects of training we need to compare a matched group of workers with and without training in their subsequent careers, but that goes beyond the purpose of this paper. That people though with job related training tend to have better income and employment opportunities in Britain suggest that training matters to people’s careers.

The investment in a healthy lifestyle seem to pay-off since people active in sports or exercising are happier and more income secure in both countries. They are also more employment secure in Germany but not in Britain. Earlier we reported already on the effect of religion on subjective well-being as part of the capabilities; the results on attending religious events show positive effects on life satisfaction but not on income or employment security.

The investments in social capital not always pay off while it seems to be related to the amount of time people invest. Time spent to volunteer work has a negative effect on income and employment security in Britain but a positive effect in Germany. There seems to be a trade-off between the time invested in volunteering leaving less time to spend in formal work (Britain) and the positive impact of the building up of social capital through volunteering on the career (Germany). The time spent to visit relatives and friends during weekdays also harms income security as well as life satisfaction though visiting relatives and friends occasionally (social networking) improves the employment security.

Events

Events exert a rather strong impact on all three WB measures in both countries though the effects are rather dissimilar. Unexpectedly, we find that the birth of a first child raises people’s life satisfaction in Britain and Germany but also their income and employment security at least in Britain. In Germany the birth of the first child lowers people’s income and employment security. We already referred earlier to the ‘life cycle squeeze’ thesis for an explanation. It might be that fathers in Britain after childbirth tend to invest more in work to compensate the income loss of their partner and aimed at raising the household income to cover the additional costs of children (Fouarge et al. 2010). The effect of second and following childbirths on employment security is negative in Britain. Divorce harms people’s life satisfaction in both countries but remarkably not people’s income and employment security, at least in Britain. The transition into early retirement harms all three forms of well-being in Germany, but only the employment security and not people’s life satisfaction or income security in Britain. Rather strong adverse effects on income and employment security but also on life satisfaction are observed for unemployment experiences in the past in Germany and Britain. Stopping one’s business has especially a negative impact on life satisfaction in Germany but exerts no strong effects on subjective or objective well-being in Britain. These results confirm the existence of strong ‘scarring’ effects of unemployment on well-being and suggest that people seem to recoup with great difficulty from unemployment experiences in the past (Clark et al. 2008a; Muffels 2008).

Conclusions and Discussion

The empirical findings render strong support for the capabilities and functionings approach of Sen. The results are generally very plausible and confirm the findings of earlier research. The outcomes show the added value of Sen’s capability approach for explaining objective and subjective well-being and their evolution over time. Because the aim of the paper is to examine the added-value of Sen’s capability approach for explaining well-being we did not look into the relationships between the various well-being measures which is however an interesting issue for future research. The low correlations though between the measures show that the concepts seem to be rather different.

The stocks indicating Sen’s capabilities seem particularly important for explaining income security and employment security in both countries whereas the personality traits exert the largest impact on SWB and only a small effect on income and employment security in both countries. Choices and events exert a large impact in all three models both in Britain and Germany whereby choices in particular affect SWB and events in particular income and employment security. This evidence on the impact of choices on SWB confirms earlier results (Headey et al. 2010) but also challenges the idea as in set-point theory (Diener et al. 1999) that SWB is rather stable over time. All models perform rather satisfactory with a view to the explained variance, including the fixed effects models. The reason might be that the long-running German panel but also the shorter British panel allow the researcher to include a rather rich set of covariates in the models which are required to test Sen’s capability model.

Overall, the results appear fairly robust in the models and we consider it reassuring that the fixed effects models reveal no different picture from the random effects models except for a very few variables indicating that correcting for the correlation between the unobserved individual effects and the observables does not do much harm to the parameter estimates of the models suggesting that most of the variance is captured with the observables in the models.

The results further show that the effects of most variables are very similar across the two countries except for some. Germany has a better record in maintaining income security and Britain a better record in maintaining employment security especially for females. Whether that should be attributed to the different ‘skill’ regime in the two countries remains to be seen. But we do find evidence in our models that the human capital variables such as education level and training efforts behave very differently across the two regimes. We argued that the dissimilar outcomes seem to mirror the differences between a ‘general skills’ regime as Britain is and a ‘specific skills’ regime as Germany is. Since the evidence is not conclusive yet, there is reason for further scrutiny into the issue.

Rather strong positive effects are observed of the social capital variables such as trust, social networks (bonding social capital) and social participation or membership (bridging social capital) on income and employment security though not on SWB. We also find support for the impact of cultural capital factors like the willingness to take risks and social and economic life goals and values such as altruism and trust. Strong positive effects are observed for risk taking behavior on income and employment security in Germany but negative effects on life satisfaction. Social values raise people’s life satisfaction in both countries. The results therefore convincingly show that along with human capital and economic values, social capital and social values significantly contribute to explaining changes in well-being confirming earlier findings (Headey et al. 2010, 2011; Muffels and Kemperman 2011).

The aim of the paper is to use a broad set of measures derived from the rich theoretical literature on well-being to test whether the capability approach of Sen translated into an empirical ‘capabilities-choices’ model of well-being has added value. We showed that Sen’s approach makes sense to arrive at a better understanding of long-term changes in objective and subjective well-being. The capability approach adds to our knowledge about what raises people’s long-term well-being with a view to income and employment security and how satisfied people are with their lives.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix: Estimation Results

Table 6.

GLS random (RE) and fixed effects (FE) models on subjective well-being (SWB), income security (YS) and employment security (ES), Germany, 1984–2008, population 16–64 years

| SWB–RE | SWB–FE | YS–RE | YS–FE | ES–RE | ES–FE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | ||||||

| Age | −0.037*** | −0.028*** | 0.054*** | 0.057*** | 3.244*** | 3.152*** |

| Age squared/100 | 0.042*** | 0.016*** | −0.054*** | −0.057*** | −4.153*** | −3.992*** |

| Household type | ||||||

| Couple, child 0–5 | 0.050** | 0.044* | −0.199*** | −0.195*** | −5.298*** | −5.511*** |

| Couple, child 6–15 | 0 | 0 | −0.117*** | −0.109*** | −0.640** | −1.010*** |

| Single, no child | −0.220*** | −0.163*** | −0.108*** | −0.047** | −0.08 | −0.05 |

| Single parent, child 0–5 | −0.380*** | −0.285*** | −0.304*** | −0.248*** | −5.599*** | −4.520*** |

| Single parent, child 6–15 | −0.356*** | −0.272*** | −0.275*** | −0.220*** | 1.974*** | 2.117*** |

| Other | −0.060*** | −0.064*** | −0.028** | −0.013 | −0.945*** | −1.094*** |

| Number of children 0–15 | 0.023** | 0.021* | −0.134*** | −0.136*** | −2.303*** | −2.148*** |

| Female (ref. male) | 0.103*** | – | 0.041*** | – | −6.654*** | – |

| Number of other employed | 0.035*** | 0.031*** | 0.036*** | 0.026*** | −0.202** | −0.263** |

| East | −0.514*** | – | −0.503*** | – | −1.421*** | – |

| Foreign | −0.033 | – | −0.301*** | – | 0.145 | – |

| Unempl-rate × Period | −0.014*** | −0.009*** | −0.005*** | −0.006*** | 0.030*** | −0.02 |

| Traits | ||||||

| Neuroticism | −0.217*** | – | −0.059*** | – | −0.544*** | – |

| Extroversion | 0.040*** | – | −0.003 | – | 0.151 | – |

| Openness | 0.034*** | – | 0.067*** | – | −0.363*** | – |

| Agreableness | 0.053*** | – | −0.059*** | – | −0.364*** | – |

| Conscientiousness | 0.068*** | – | −0.032*** | – | 1.266*** | – |

| Capabilities | ||||||

| Highest completed education(ref. low education) | ||||||

| High education | 0.099*** | 0.042 | 0.268*** | 0.051* | 3.858*** | 3.373*** |

| Intermediate education | 0.001 | −0.033 | −0.042*** | −0.096*** | 1.018*** | 0.393 |

| Health | ||||||

| Work disability | −0.245*** | −0.159*** | −0.087*** | −0.063*** | −6.995*** | −6.030*** |

| Handicapped | −0.321*** | −0.243*** | −0.049*** | −0.034** | −4.430*** | −4.498*** |

| Social–cultural capital | ||||||

| Social network | 0.094*** | 0.073*** | −0.029*** | −0.032*** | −0.687*** | −0.569*** |

| Member trade union | −0.029 | −0.029 | −0.013 | 0.019 | 2.887*** | 2.193*** |

| Trust | 0.274*** | 0.108*** | 0.067*** | −0.006 | 0.505*** | −0.236 |

| Risktaking | 0.022*** | 0.027*** | 0.013*** | 0.001 | 0.078** | −0.111* |

| Religion (ref.: catholic) | ||||||

| Protestant | −0.017 | −0.069 | −0.02 | −0.023 | −0.221 | 0.339 |

| Other Christian | −0.125** | −0.063 | 0.005 | 0.120** | 0.76 | 1.397 |

| Other religion | −0.242*** | 0.042 | −0.118*** | 0.097* | −2.147*** | 1.118 |

| No denomination | −0.075*** | −0.065 | 0.045** | 0.072** | 0.243 | 1.213** |

| Life goals | ||||||

| Social goals | 0.084*** | 0.068** | 0.011 | −0.029 | −1.057*** | −1.338*** |

| Family goals | 0.140*** | 0.130*** | 0.030*** | 0.046*** | −0.174 | −0.097 |

| Material/success goals | 0.01 | 0.055** | 0.068*** | 0.044*** | 4.584*** | 4.542*** |

| Functionings/choices | ||||||

| Overtime in work | 0.005*** | 0.006*** | 0.005*** | 0.004*** | 0.325*** | 0.306*** |

| Job (hours) match (ref. match) | ||||||

| Underworked employed | −0.215*** | −0.181*** | −0.035*** | −0.035*** | 5.622*** | 4.884*** |

| Overworked employed | −0.060*** | −0.047*** | 0.090*** | 0.077*** | 6.507*** | 5.578*** |

| Underworked unemployed | −0.775*** | −0.713*** | −0.176*** | −0.160*** | −18.966*** | −18.251*** |

| Underworked inactive | −0.427*** | −0.387*** | −0.113*** | −0.100*** | −14.533*** | −12.894*** |

| Type of training (ref. no training) | 0.001 | −0.018 | −0.117*** | −0.136*** | 0.23 | 0.358 |

| Apprentice | −0.048* | −0.027 | −0.143*** | −0.164*** | −20.593*** | −19.527*** |

| Time use | ||||||

| Time spent on exercise/sports | 0.046*** | 0.035*** | 0.029*** | 0.010*** | 0.400*** | 0.282*** |

| Time spent on volunteer work | −0.008 | −0.005 | 0.002 | −0.004 | 0.453*** | 0.392*** |

| Attend social events | 0.175*** | 0.152*** | 0.059*** | 0.029*** | 0.581*** | 0.473** |

| Attend religious events | 0.052*** | 0.019* | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.043 | −0.122 |

| Events | ||||||

| Involuntary job change | −0.022 | 0.004 | −0.050*** | −0.040*** | 2.073*** | 2.128*** |

| Start own business | −0.03 | −0.034 | 0.050* | 0.014 | 0.784* | 0.910* |

| Stop own business | −0.164*** | −0.160*** | −0.038 | −0.071** | 0.64 | 0.347 |

| First childbirth | 0.206*** | 0.210*** | −0.116*** | −0.119*** | −4.597*** | −4.420*** |

| Birth second, third child | 0.138 | 0.153 | −0.035 | −0.028 | −0.316 | −0.19 |

| Divorced or separated | −0.350*** | −0.349*** | 0.008 | −0.006 | −0.980*** | −1.142*** |

| Marriage/cohabitation | 0.226*** | 0.253*** | 0.115*** | 0.135*** | 0.948*** | 0.923*** |

| Early retirement event | −0.066* | −0.070** | −0.109*** | −0.112*** | −16.308*** | −16.823*** |

| Unemployment event in past | −0.043*** | 0.007 | −0.076*** | −0.065*** | −1.378*** | −1.207*** |

| Constant | 5.522*** | 6.229*** | 0.828*** | 0.794*** | −26.855*** | −28.387*** |

| R squared | 0.188 | 0.104 | 0.224 | 0.125 | 0.546 | 0.511 |

| N | 163,550 | 163,550 | 151,588 | 151,588 | 136,824 | 136,824 |

| Sigma U | 0.938 | 1.226 | 0.841 | 1.026 | 10.331 | 13.541 |

| Sigma E | 1.237 | 1.237 | 0.615 | 0.615 | 11.496 | 11.496 |

| Rho | 0.365 | 0.495 | 0.652 | 0.736 | 0.447 | 0.581 |

* p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01

Table 7.

GLS random (RE) and fixed effects (FE) models on subjective well-being (SWB), income security (YS) and employment security (ES), Great-Britain 1991/1996–2008, population 16–64 years

| SWB–RE | SWB–FE | YS–RE | YS–FE | ES–RE | ES–FE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls | ||||||

| Age | −0.066*** | −0.047*** | 0.095*** | 0.097*** | 2.713*** | 2.855*** |

| Age squared/100 | 0.082*** | 0.055*** | −0.113*** | −0.117*** | −3.450*** | −3.547*** |

| Household type | ||||||

| Couple, young child 0–5 | −0.013 | −0.041 | −0.598*** | −0.626*** | −2.247*** | −2.987*** |

| Couple, young child 6–15 | −0.064** | −0.073** | −0.512*** | −0.509*** | 0.081 | −0.352 |

| Single, no child | −0.347*** | −0.229*** | −0.267*** | −0.261*** | −1.023*** | −0.514 |

| Single parent, young child 0–5 | −0.503*** | −0.357*** | −0.687*** | −0.673*** | −5.352*** | −5.138*** |

| Single parent, young child 6–15 | −0.405*** | −0.239*** | −0.740*** | −0.693*** | −0.794 | −0.649 |

| Other | −0.136*** | −0.104** | −0.348*** | −0.338*** | −2.571*** | −1.969*** |

| No. of kids 0–15 | −0.016 | 0.019 | −0.366*** | −0.355*** | −1.573*** | −1.439*** |

| Gender (1 = female) | 0.094*** | – | −0.024 | – | −4.477*** | – |

| Number of other employed in HH | −0.022** | −0.027** | 0.163*** | 0.158*** | 1.122*** | 0.756*** |

| Not born in Britain | −0.181 | 0.255 | −0.123 | −0.032 | −5.657 | −2.763 |

| Unemployment rate × period | −0.023*** | −0.019*** | −0.006** | −0.002 | 0.157*** | 0.070* |

| Traits | ||||||

| Neuroticism | −0.340*** | – | −0.036*** | – | −0.639*** | – |

| Extroverticism | 0.092*** | – | 0.004 | – | 0.223** | – |

| Openness | −0.047*** | – | 0.043*** | – | −0.059 | – |

| Agreableness | 0.106*** | – | −0.091*** | – | −0.515*** | – |

| Conscientiousness | 0.153*** | – | 0.020** | – | 1.074*** | – |

| Capabilities | ||||||

| Highest completed education (ref.: low education) | ||||||

| High education (isced) | −0.069* | 0.215* | 0.639*** | 0.158*** | 5.743*** | 4.338*** |

| Intermediate education (isced) | −0.076** | 0.254** | 0.198*** | −0.095* | 3.426*** | −0.46 |

| Health limitations at work | −0.622*** | −0.445*** | −0.129*** | −0.073*** | −5.699*** | −3.452*** |

| Member trade union | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.108*** | 0.102*** | 4.507*** | 4.235*** |

| Social–cultural capital trust | 0.134*** | 0.095*** | 0.051*** | 0.012 | 0.178 | 0.068 |

| Religion (ref.: catholic) | ||||||

| Protestant | 0.108*** | 0.062 | 0.033 | −0.025 | 0.723** | −0.556 |

| Other Christian | 0.106** | 0.086 | −0.013 | −0.081 | 0.356 | −0.588 |

| Other religion | −0.011 | 0.108 | 0.008 | −0.015 | −0.9 | −1.085 |

| No denomination | 0.073** | 0.069 | 0.039 | −0.008 | 1.180*** | 0 |

| Social contacts | 0.101*** | 0.087*** | −0.026*** | −0.003 | −0.554*** | −0.503*** |

| Life goals | ||||||

| Material/success goals | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 1.628*** | 1.505*** |

| Social goals | 0.117*** | 0.114*** | −0.007 | 0.006 | −0.122 | −0.365** |

| Functionings—choices | ||||||

| Overtime | 0 | 0.001 | 0.014*** | 0.012*** | 0.208*** | 0.190*** |

| Job (hours) match (ref. fit) | ||||||

| Underworked employed | −0.148*** | −0.097*** | −0.078*** | −0.058*** | 4.560*** | 4.101*** |

| Overworked employed | −0.159*** | −0.141*** | 0.178*** | 0.158*** | 4.949*** | 4.225*** |

| Underworked unemployed | −0.466*** | −0.431*** | −0.077** | −0.069* | −6.101*** | −6.505*** |

| Underworked inactive | −0.284*** | −0.200*** | −0.120*** | −0.106*** | −17.762*** | −16.312*** |

| Type of training (ref. no training) | ||||||

| Government training | −0.059 | −0.099 | 0.021 | 0.044 | −5.832*** | −5.646*** |

| Apprenticeship | 0.280** | 0.251 | 0.1 | 0.218** | 10.061*** | 10.151*** |

| Training on the job | 0.037*** | 0.040*** | 0.082*** | 0.063*** | 3.663*** | 3.232*** |

| Training when inactive | 0.003 | 0.012 | −0.047* | −0.050** | −4.694*** | −4.035*** |

| Time use | ||||||

| Time spent to exercise/sports | 0.066*** | 0.046*** | 0.012*** | 0.002 | −0.104* | −0.205*** |

| Time spent to volunteer work | 0.008 | 0.011 | −0.035*** | −0.035*** | −0.767*** | −0.681*** |

| Attend social events | 0.205*** | 0.177*** | 0.145*** | 0.074*** | 1.724*** | 0.900*** |

| Attend religious events | 0.055*** | 0.026** | 0.005 | −0.004 | −0.043 | −0.032 |

| Events | ||||||

| Start own business | 0.068 | 0.080* | −0.054 | −0.059* | 0.254 | −0.011 |

| Stop own business | −0.057 | −0.046 | −0.056* | −0.059* | 0.321 | −0.224 |

| First childbirth | 0.242*** | 0.250*** | 0.097*** | 0.099*** | 2.092*** | 2.227*** |

| Birth second, third child | 0.064* | 0.056 | 0.038*** | 0.029** | −0.581** | −0.572** |

| Divorced or separated | −0.467*** | −0.479*** | 0.071** | 0.072** | 1.027*** | 0.650* |

| Marriage/cohabitation | 0.192*** | 0.243*** | −0.107*** | −0.092*** | 0.508* | 0.575** |

| Involuntary job change | −0.027 | −0.009 | −0.041* | −0.032 | 2.298*** | 1.920*** |

| Early retirement event | 0.176*** | 0.174*** | −0.006 | −0.009 | −3.072*** | −2.475*** |

| Unemployment events in past | −0.215*** | −0.190*** | −0.096*** | −0.056* | −7.821*** | −6.280*** |

| Constant | 5.321*** | 5.566*** | 0.381*** | 0.477*** | −22.132*** | −21.871*** |

| R squared | 0.195 | 0.112 | 0.329 | 0.283 | 0.445 | 0.394 |

| N | 93,648 | 93,648 | 111,464 | 111,464 | 110,794 | 110,794 |

| Sigma U | 1.199 | 1.512 | 0.86 | 1.037 | 10.609 | 14.452 |

| Sigma E | 1.37 | 1.37 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 11.805 | 11.805 |

| Rho | 0.434 | 0.549 | 0.483 | 0.576 | 0.447 | 0.6 |

* p < 0.10; ** p < 0.05; *** p < 0.01

Footnotes

The distinction between family, social and economic life goals is based on performed principal components analysis on the data (see Sect. 3 on data and methodology).

In the German panel study we were able to derive events from the annual and monthly calendar information on labour market status. The German panel contains a calendar in which information is asked about the socio-economic status of the respondent for each of the 12 months preceding the interview date. Also the British panel contains monthly information on people’s activities. The calendar information permits to assessing changes over people’s work history and life course. Most of the events are however derived from the annual information at the time of the interview.

The interpretation of the occurring differences between the two countries is not straightforward since sample and design differences might impact the comparison. The sample framework and design though of these two panel studies are however very similar (see Sect. 3.1).

Because SWB is basically an ordinal scale some researchers used ordered probit or ordered logit for estimation. However, since the scale ranges from 0 to 7 in Britain and 0–10 in Germany (and hence contains 7–11 mass points), the linearity assumption as implied by treating it as a cardinal scale is not seriously violated. A test using Kernel density estimates and kernel density plots on the data confirms this.

Contributor Information

Ruud Muffels, Phone: +31-134-662795, Email: Ruud.J.Muffels@uvt.nl.

Bruce Headey, Email: b.headey@unimelb.edu.au.

References

- Alkire S. Choosing dimensions: The capability approach and multidimensional poverty. In: Silber J, editor. The many dimensions of poverty. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ball R, Chernova K. Absolute income, relative income, and happiness. Social Indicators Research. 2008;88:497–529. doi: 10.1007/s11205-007-9217-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Frijters P, Shields M. Relative income, happiness and utility: An explanation for the Easterlin paradox and other puzzles. Journal of Economic Literature. 2008;46(1):95–144. doi: 10.1257/jel.46.1.95. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Clark A, Diener E, Georgellis Y, Lucas RE. Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. Economic Journal. 2008;118:222–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cuven, C., Senik, C., & Stichnoth, H. (2010). You can’t be happier than your wife, happiness gaps and divorce, ISSN 1864-6689, SOEP Papers, No. 261, DIW Berlin.

- Diener E, Oishi S. Money and happiness: Income and subjective well-being across nations. In: Diener E, Suh EM, editors. Culture and subjective well-being. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2000. pp. 185–218. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125:276–302. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.2.276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dohmen T, Falk A, Huffman D, Sunde U, Schupp J, Wagner GG. Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association. 2011;9(3):522–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin RA. Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal. 2001;111(July):465–484. doi: 10.1111/1468-0297.00646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Estéves-Abe M, Iversen T, Soskice D. Social protection and the formation of skills: A reinterpretation of the welfare state. In: Hall P, Soskice D, editors. The institutional foundations of comparative advantage. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 145–183. [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7(2):117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fouarge D, Manzoni A, Muffels R, Luijkx R. Childbirth and cohort effects on mother’s labour supply: A comparative study using life‐history data for Germany, the Netherlands and Great‐Britain. Work, Employment and Society. 2010;24(3):487–507. doi: 10.1177/0950017010371651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gangl M. Scar effects of unemployment: An assessment of institutional complementarities. American Sociological Review. 2006;71(December):9861013. [Google Scholar]

- Hall P, Soskice D, editors. Varieties of capitalism: the institutional foundations of comparative advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Headey, B. (1993). An economic model of subjective well‐being: Integrating economic and psychological theories. Social Indicators Research, 28(1), 97–116.

- Headey, B. (2008). Life goals matter to happiness: A revision of set‐point theory. Social Indicators Research, 86(2), 213–231.

- Headey, B., & Wearing, A. J. (1992). Understanding Happiness. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire.

- Headey, B., Muffels, R., & Wooden, M. (2008). Money does not buy happiness: Or does it? A reassessment based on the combined effects of wealth, income and consumption. Social Indicators Research, 87(1), 65–82.

- Headey, B. W., Muffels, R. J. A., & Wagner, G. G. (2010). Long‐running German panel survey shows that personal and economic choices, not just genes, matter for happiness, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(42), 17922–17926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]