Abstract

The first genetic defect in human signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)5b was identified in an individual with profound short stature and GH insensitivity, immune dysfunction, and severe pulmonary disease, and was caused by an alanine to proline substitution (A630P) within the Src homology-2 (SH2) domain. STAT5bA630P was found to be an inactive transcription factor based on its aberrant folding, diminished solubility, and propensity for aggregation triggered by its misfolded SH2 domain. Here we have characterized the second human STAT5b amino acid substitution mutation in an individual with similar pathophysiological features. This single nucleotide transition, predicted to change phenyalanine 646 to serine (F646S), also maps to the SH2 domain. Like STAT5bA630P, STAT5bF646S is prone to aggregation, as evidenced by its detection in the insoluble fraction of cell extracts, the presence of dimers and higher-order oligomers in the soluble fraction, and formation of insoluble cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in cells. Unlike STAT5bA630P, which showed minimal GH-induced tyrosine phosphorylation and no transcriptional activity, STAT5bF646S became tyrosine phosphorylated after GH treatment and could function as a GH-activated transcription factor, although to a substantially lesser extent than STAT5bWT. Biochemical characterization demonstrated that the isolated SH2 domain containing the F646S substitution closely resembled the wild-type SH2 domain in secondary structure, but exhibited reduced thermodynamic stability and altered tertiary structure that were intermediate between STAT5bA630P and STAT5bWT. Homology-based structural modeling suggests that the F646S mutation disrupts key hydrophobic interactions and may also distort the phosphopeptide-binding face of the SH2 domain, explaining both the reduced thermodynamic stability and impaired biological activity.

GH plays a pivotal role in multiple physiological processes in humans and in other mammals. It is essential for somatic growth, is a key contributor to normal tissue differentiation and repair, and is an important regulator of intermediary metabolism (1, 2). In children, genetic mutations in components of the GH-IGF-I-growth pathway cause growth deficiency and short stature (3, 4). Whereas the majority of these children lack GH and benefit from hormone replacement therapy (5, 6), a significant fraction have been found to have GH insensitivity, either because of inactivating mutations in the GH receptor or from defects in other downstream signaling molecules (4, 7, 8).

The GH receptor is a member of the cytokine receptor family (1, 9). Hormone binding induces activation of the receptor-associated tyrosine kinase, JAK (Janus family of tyrosine kinases)2, leading to phosphorylation of tyrosine residues on the intracellular part of the receptor, and recruitment of signaling molecules (1, 9). Despite clear evidence that several signaling pathways act downstream of the GH receptor, multiple observations have implicated the transcription factor STAT5b (signal transducer and activator of transcription) as the essential signaling intermediate responsible for normal regulation of somatic growth and for many of the other biological actions of GH (7, 10–15).

The first STATs were characterized in the early 1990s as signaling agents for interferons α/β and γ (16, 17), and subsequent studies have broadened the biological importance of this protein family as critical components of multiple physiological processes (18–21). STATs are multidomain proteins (18) that are typically found in the cytoplasm of responsive cells before cytokine or hormonal stimulation (18–20) and are recruited to phosphorylated tyrosine residues on intracellular segments of activated receptors via their Src homology-2 (SH2) domains, where they become phosphorylated on a tyrosine near the STAT COOH-terminus by a receptor-linked tyrosine protein kinase, usually JAK1–3, or TYK2 (18–20). After dissociation from the receptor-docking site, STATs form dimers via reciprocal interactions of the SH2 domain on one STAT molecule with the phosphorylated tyrosine on the other (18) and are translocated into the nucleus, where they bind as dimers to specific DNA sites in chromatin (18–21).

The first genetic defect in human STAT5b was identified in an individual with profound short stature, immune dysfunction, and severe pulmonary disease (14). Subsequent studies have identified 10 subjects with homozygous STAT5B gene mutations. All have been found to have growth deficiency and evidence of defects within the immune system, ranging from atopy to severe eczema (22). Based on molecular characterization of the mutations, it seems likely that eight of the 10 individuals do not synthesize full-length STAT5b protein, because predicted homozygous nucleotide changes introduce frame-shifts and stop codons that truncate the mRNA reading frame (7). Two subjects have been found with predicted homozygous amino acid substitution mutations caused by single nucleotide transversions/transitions (7, 14, 23). In the first case, in which alanine codon 630 was changed to a proline (A630P) within the SH2 domain, the mutant STAT5b protein detected in the individual's fibroblasts was shown to be prone to aggregation and accumulated in cells within cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (24).

Here we characterize the second naturally occurring human STAT5b amino acid substitution mutation. This single nucleotide transition, which is predicted to change phenylalanine 646 to serine (F646S), also maps to the SH2 domain (23). We find that this defective protein shares several biochemical and biophysical features with STAT5bA630P, including a propensity toward protein aggregation, but unlike STAT5bA630P retains residual transcription factor activity.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Fetal calf serum, DMEM, and PBS were obtained from Mediatech-Cellgro (Herndon, VA). The QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit was from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA), and Transit-LT1 was from Mirus (Madison, WI). Recombinant rat GH was from the National Hormone and Pituitary Program, National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease, National Institutes of Health. Restriction enzymes, ligases, polymerases, and protease inhibitor tablets were purchased from Roche Applied Sciences (Indianapolis, IN), and trypsin/EDTA solution was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). AquaBlock solution was from East Coast Biologic (North Berwick, ME); the BCA and 660 nm protein assay kits and GelCode blue were from Pierce Biotechnologies (Rockford, IL); and tissue culture grade BSA was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Okadaic acid was from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA), and QIA-Quick PCR purification kit was from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA). Oligonucleotides were synthesized at the Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) DNA Services Core, at Oligos Etc (Wilsonville, OR), and at Eurofms MWG Operon (Huntsville, AL). The following primary antibodies were obtained from vendors: anti-phospho-STAT5 (clone 8-5-2) and anti-cAMP response element-binding protein from Millipore Corp. (Billerica, MA); anti-STAT5b from Invitrogen; and anti-α-tubulin and anti-FLAG (M2) from Sigma-Aldrich. Goat-antirabbit IgG-IR800 and goat antimouse IgG-IR680 were from Rockland Immunochemical (Gilbertsville, PA); and goat antimouse IgG1-Alexa 488 was from Invitrogen-Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Hoechst 33258 nuclear dye was obtained from Polysciences (Warrington, PA). DNA sequencing was performed at the OHSU DNA services core facility. All other chemicals were reagent grade and were purchased from commercial suppliers.

Recombinant plasmids

Expression plasmids for FLAG-tagged full-length human wild-type (WT) and mutant STAT5b (F646S and A630P), and the mouse GH receptor in pcDNA3 have been described elsewhere (23, 25), as have luciferase reporter gene plasmids containing Stat5b-binding elements from the rat Igf1 gene fused to rat Igf1 promoter 2 and exon 2 (26). DNA encoding SH2 domains of wild-type (WT) and mutant human STAT5b (from codon D591 to E689) was amplified by PCR and cloned into pET-15b (Novagen, San Diego, CA) using NdeI and XhoI restriction sites so that a hexa-histidine tag was added to the NH2 terminus.

Cell culture and transient transfections

Cos-7 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA; catalog no. CRL-1651) were incubated in DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 C in humidified air with 5% CO2. For detection of STAT5b by immunoblotting or immunocytochemistry, cells in six-well dishes were transfected 1 d after seeding with expression plasmids for human STAT5b (200 ng of DNA for WT or 600 ng for each mutant) and the GH receptor (100 ng), incubated the next day in serum-free medium plus 1% BSA and analyzed after addition of recombinant rat GH (40 nm) or vehicle for 30–120 min. For luciferase reporter assays, cells were seeded in 12-well plates and cotransfected on the following day with expression plasmids for STAT5b (50 ng or 150 ng WT, 150 ng F646S, or 150 ng A630P, or combinations of 50 ng of WT with 50 or 100 ng F646S, A630P, or enhanced green fluorescent protein), GH receptor (25 ng), and one of several luciferase reporter plasmids (75 ng). Cells were incubated 1 d later in serum-free medium with 1% BSA plus GH or vehicle. Cell lysates were prepared 16–18 h later for luciferase assays (Promega Corp., Madison, WI), as described elsewhere (24, 26).

Immunoblotting and immunocytochemistry

Whole cell and nuclear and cytoplasmic protein lysates were prepared as described (25–27), and separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (25–27) using 10 μg of whole cell, 10 μg of cytoplasmic, or 5 μg of nuclear extracts. Insoluble material (see Fig. 4A) was suspended in electrophoresis sample buffer containing 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate (24). Studies of protein oligomerization were performed using cytoplasmic protein extracts analyzed by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis (6% polyacrylamide), as in Ref. 28. Primary and secondary antibodies for immunoblotting were used at a 1:4000 dilution, except for anti α-tubulin (1:10,000). Proteins were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes in buffer containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate for 2 h at 400 mA at 4 C. Images were captured with the Li-CoR Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (Li-CoR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and version 3.0 analysis software. Immunocytochemistry was performed using cells that were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at 20 C and permeabilized with a 50% acetone-50% methanol solution for 2 min, followed by overnight incubation at 4 C with normal goat serum. Primary and secondary antibodies were used at 1:2000 dilutions. Images were visualized with a Nikon Eclipse Ti-U inverted microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY), and data were collected by a Nikon DS-Qi1Mc camera, and analyzed using NIS-Elements imaging software (version 3.10). Results represent the compilation of at least 100 transfected cells from each of four independent experiments.

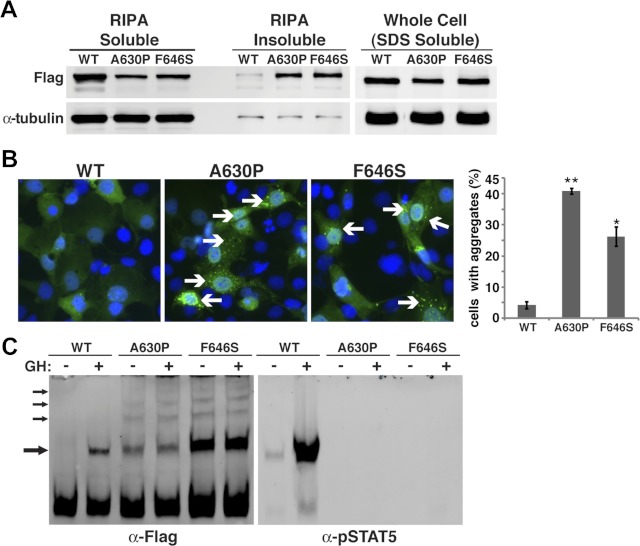

Fig. 4.

STAT5bA630P and STAT5bF646S accumulate in cells in insoluble protein aggregates. A, Results of immunoblotting of proteins isolated from Cos-7 cells transiently transfected with expression plasmids for Flag-tagged STAT5bWT, STAT5bA630P, or STAT5bF646S and fractionated by solubility in radioimmune precipitation assay (RIPA) buffer. B (left), Immunocytochemistry of transiently transfected Cos-7 cells for STAT5b using Flag M2 antibody (green). Nuclei are stained with Hoechst dye (blue). Cells with STAT5b aggregates are indicated by arrows. B (right), Graph depicting the percentage of cells transfected with each STAT5b variant that exhibited protein aggregation (mean ± se; **, P < 0.0003 for STAT5bWT vs. STAT5bA630P; *, P < 0.01 for STAT5bWT vs. STAT5bF646S). C, Results of immunoblotting for Flag or pStat5 of cytoplasmic protein extracts separated by nondenaturing, nonreducing gel electrophoresis of Cos-7 cells transiently transfected with expression plasmids for mouse GH receptor and either Flag-tagged STAT5bWT, STAT5bA630P, or STAT5bF646S, and incubated with rat GH (40 nm) or vehicle for 30 min. Arrows point to dimers and multimers.

DNA-protein binding studies

EMSAs were performed as described (26) with 4 μg of Cos-7 nuclear protein extracts and 5′-Cy5.5-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides (60 fmol each).

Purification of SH2 domains

Escherichia coli strain BL21 cells transformed with pET15b expression plasmids for WT and mutant STAT5b SH2 domains were grown as described elsewhere (24). Recombinant proteins were extracted from insoluble inclusion bodies using guanidine HCl (6 m), and purified using nickel-NTA column chromatography under denaturing conditions in the presence of 8 m urea. Purification was monitored by SDS-PAGE and staining with GelCode blue reagent. Proteins were refolded either by dialysis against an approximately 100,000-fold larger volume of refolding buffer (20 mm NaH2PO4, 150 mm NaCl, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.5) for circular dichroism (CD) experiments, or by rapid dilution into refolding buffer for fluorescence measurements.

CD spectroscopy

CD spectra were collected from refolded and purified SH2 domain proteins using a model 215 Circular Dichroism Spectrometer (Aviv Instruments, Inc., Lakewood, NJ) with samples maintained at 4 C. Far-UV spectra were collected using protein samples (25 μm) in 1-mm path length quartz cuvettes from 260–195 nm. Near-UV spectra were collected from protein samples (20–60 μm) in 10-mm path length quartz cuvettes from 320–250 nm. Chemical denaturation studies were conducted at 20 C by monitoring protein samples at 222 nm in 10-mm path length quartz cuvettes after step-wise titration with guanidine HCl using a Hamilton Microlab 500 titrator (Hamilton Co., Reno, NV) connected to the spectrometer. Refolding buffer with 6 m guanidine HCl was added to protein samples maintained at a constant volume under continual stirring such that denaturant concentrations increased from 0–5 m in 0.05 m steps at 3.5-min intervals between steps. The initial protein concentration in these studies was 5 μm. Results represent the mean of three to four experiments performed with at least three independently purified and refolded batches of protein for each SH2 domain.

Fluorescence spectroscopy

Fluorescence spectra of purified SH2 domains were collected using a Photon Technology International spectrometer with a model 810 photo-multiplier detection system at 20 C using 10-nm slit widths. For measurement of intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, each protein solution (50 μm) was refolded from a denatured state by a 20-fold rapid dilution into refolding buffer and then equilibrated at 20 C. Samples were excited at 295 nm and fluorescence was measured from 300–400 nm. For ANS (1 anilino-8-naphtalene sulphonic acid)-induced extrinsic fluorescence, samples were prepared by combining equal volumes of dilution-refolded protein (2.5 μm) and 50 mm ANS in refolding buffer followed by equilibration at 20 C for 60 min. Protein solutions were excited at 390 nm and measured at 400–600 nm. For protein stability studies, denatured SH2 proteins were diluted 20-fold into refolding buffer containing 0–6 m guanidine HCl and equilibrated overnight. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectra were collected and values at the emission peak of folded protein relative to the folded, and unfolded states were plotted against the final concentration of denaturant. The refolding study represents the mean of three experiments performed with independently refolded batches of each SH2 domain, and the other fluorescence spectra are representative of two to three independently purified and refolded batches of protein.

Data analysis

Paired or unpaired t tests were performed as appropriate, applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Nonlinear fits of protein denaturation curves were performed on normalized data using GraphPad Prism 5 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) using a least-squares fit to two-state sigmoidal (24) or three-state sigmoidal functions, as previously described (29).

Sequence alignment and homology models

Sequence alignments were performed using ClustalW at EMBL-EBI (30) (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/) with minor manual modifications to the αB-αC loop based on structural alignments. Homology models for WT STAT5b SH2 domain were generated based on the structure of STAT1 [PDB accession code 1YVL (31)] and STAT5a [PDB accession code 1Y1U (32)] using the SWISS-MODEL structure homology-modeling server (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/) (33–35), and mutations were created using SwissPdb Viewer (36) (http://spdbv.vital-it.ch/). Images were prepared with the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.5.04 (Schrödinger, LLC, Portland, OR).

Results

Diminished tyrosine phosphorylation but nuclear accumulation of STAT5bF646S

The domain structure of human STAT5b is depicted in Fig. 1A, with the locations indicated for the F646S mutation, the tyrosine phosphorylation site (Y699), and the previously described A630P amino acid substitution. To study the effects of the F646S mutation on STAT5b function, we transiently cotransfected WT and mutant FLAG epitope-tagged human STAT5b proteins with the GH receptor into Cos-7 cells and characterized the effects of GH treatment. GH stimulated the tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5bWT within 30 min but minimally induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5bA630P, with the response of STAT5bF646S being intermediate (Fig. 1B). Of note, steady-state levels of STAT5bWT were nearly 3-fold higher than STAT5bA630P or STAT5bF646S when equivalent amounts of DNA were transfected (Fig. 1B). Therefore, to compensate for the apparently reduced abundance of the two mutant STAT5b proteins, only one third as much WT STAT5b DNA expression vector was transfected in most subsequent experiments.

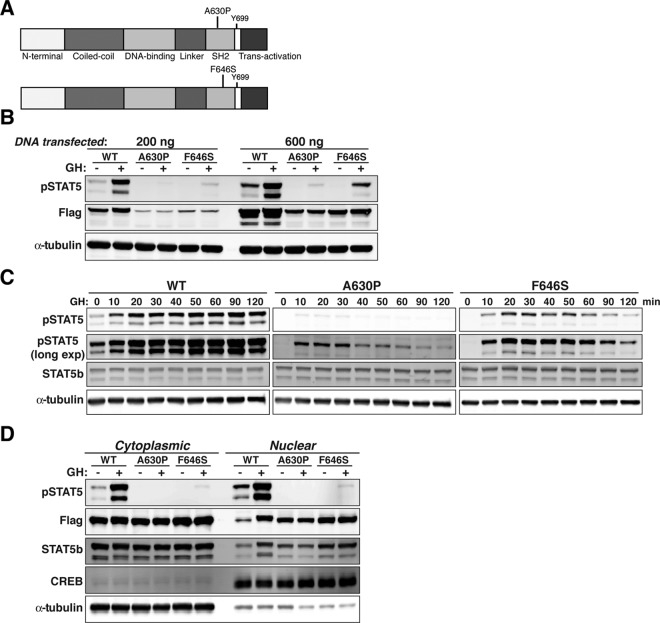

Fig. 1.

Diminished tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5bF646S after GH stimulation. A, Schematic depicting domain structure of human STAT5b, indicating locations of the A630P and F646S mutations in the SH2 domain. B, Immunoblotting for phosphorylated STAT5b on tyrosine 699 (pSTAT5), for the Flag epitope tag, and for α-tubulin after transient transfection of Cos-7 cells with expression plasmids for mouse GH receptor (100 ng) and either 200 or 600 ng of Flag-tagged STAT5b variants, and incubation with rat GH (40 nm) for 30 min. Equivalent amounts of total protein were loaded into each lane of the gel. C, Time course of tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5b variants after GH treatment. Immunoblotting for pSTAT5, for STAT5b, and for α-tubulin after transient transfection of Cos-7 cells with expression plasmids for mouse GH receptor and either 200 ng of STAT5bWT or 600 ng of STAT5bA630P or STAT5bF646S, and incubation with rat GH. D, Constitutive nuclear localization but diminished nuclear accumulation of STAT5b amino acid substitution variants after GH stimulation. Detection of pSTAT5, Flag, STAT5b, cAMP response element-binding protein, and α-tubulin by immunoblotting in nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extracts obtained before or after incubation of Cos-7 cells with rat GH for 30 min.

More thorough time course studies were performed to assess the effects of GH on tyrosine phosphorylation of the two mutant STAT5b proteins. GH induced tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5bWT within 10 min of hormone treatment, with peak levels being attained by 90–120 min (Fig. 1C). A similar onset of tyrosine phosphorylation after GH was detected for STAT5bA630P (only seen with longer imaging times) and STAT5bF646S, but peak values were achieved by 30 min for STAT5bA630P, and by 50 min for STAT5bF646S, such that by 120 min the amount of tyrosine phosphorylation for each mutant was only slightly above baseline (Fig. 1C). Thus, both mutant STAT5b proteins show reduced levels and decreased duration of GH-induced tyrosine phosphorylation compared with STAT5bWT. However, these results also indicate that both mutant STAT5b proteins are as rapidly recruited to the GH receptor and phosphorylated on tyrosine 699 by receptor-linked Jak2 as STAT5bWT.

The next steps in GH-stimulated activation of STAT5b involve their homodimerization, followed by translocation of the tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins into the nucleus (37). GH caused a robust increase in the tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT5bWT that was detected in both cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments, with an increase in its protein levels in nuclear extracts after GH treatment (Fig. 1D). In contrast, little tyrosine phosphorylation of either mutant was detected in the nucleus, even though, surprisingly, both mutant STAT5b molecules were found in nuclear protein extracts at comparable levels to GH-induced STAT5bWT, even in the absence of hormone exposure (Fig. 1D). Based on these results, both STAT5bF646S and STAT5bA630P appear to accumulate within the nucleus independent of GH treatment.

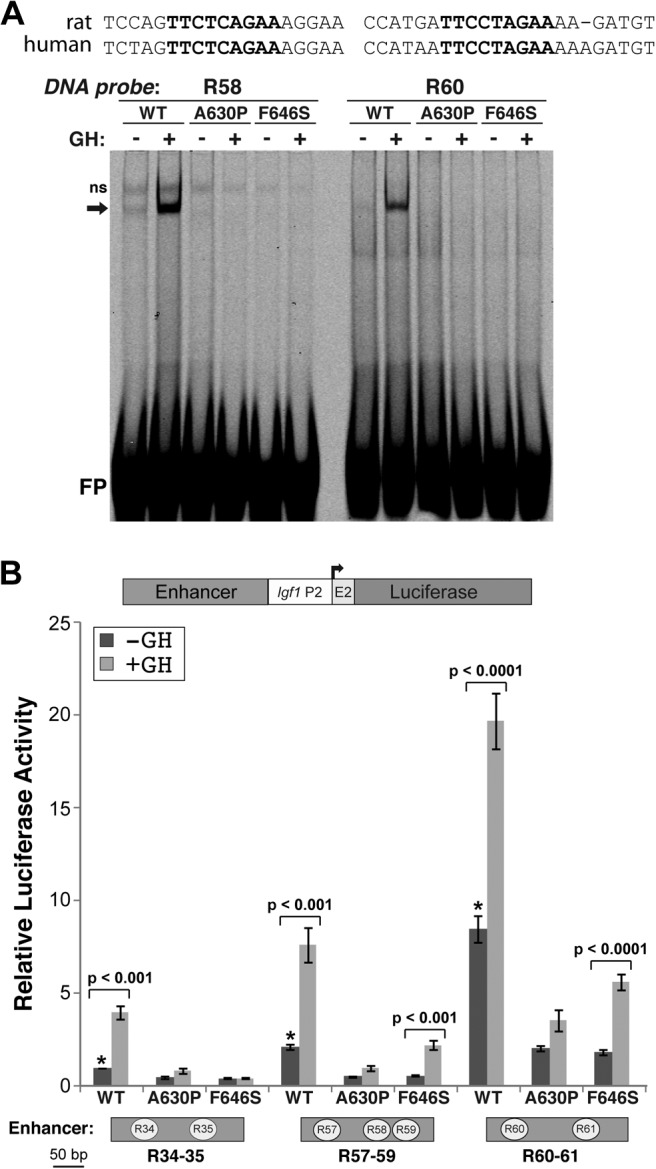

Minimal DNA binding and limited transcriptional activity of STAT5bF646S

We next examined the potential transcriptional properties of STAT5bF646S. We first assessed DNA binding capability by in vitro gel mobility-shift experiments, using nuclear protein extracts as the source of STAT5b and labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide probes from R58 and R60, two of the higher-affinity Stat5 sites identified in the rat Igf1 gene (26) that are very similar to their human counterparts (Fig. 2A). Results show that GH acutely stimulated the ability of STAT5bWT to bind to both probes, but that the mutant proteins failed to bind (Fig. 2A), even when up to 10 times more STAT5b-containing nuclear protein extract was used (data not shown). We also tested the ability of the mutant STAT5b molecules to mediate GH-stimulated gene transcription, using luciferase reporter plasmids containing rat Igf1 promoter 2 and one of three STAT5b-binding response elements from the rat Igf1 locus (26). GH was able to induce a significant rise in reporter gene expression in cells transfected with STAT5bWT. In contrast, STAT5bA630P was transcriptionally inert, as shown previously (14, 24), and STAT5bF646S gave an intermediate response, having no effect on one reporter gene (R34–35), but increasing transcription in response to GH in the other two (R57–59 and R60–61, Fig. 2B). Of note, STAT5bWT was able to induce transcription of each promoter-reporter gene even in the absence of GH treatment, results consistent with the small amount of nuclear tyrosine-phosphorylated protein detected under these conditions (see Fig. 1, B–D).

Fig. 2.

Reduced DNA binding and transcriptional activity of STAT5bF646S after GH stimulation. A, DNA-protein binding activity was assessed by gel-mobility shift experiments using Cy5.5-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides for rat Igf1 gene Stat5b binding elements R58 or R60, and 1 μg of nuclear protein from Cos-7 cells transfected with expression plasmids for the mouse GH receptor and STAT5b variants, and incubated with rat GH (40 nm) for 30 min. The DNA sequences of the corresponding rat and human R58 and R60 segments are aligned above the gel-mobility shift image. The core Stat5b binding sequence is in bold script; ns, nonspecific band; FP, free probe. B (top), Schematic of luciferase reporter plasmids containing rat Igf1 promoter 2 (P2) and exon 2, and individual Stat5b binding elements (Enhancer). B (bottom), Results of luciferase assays after transient transfection of Cos-7 cells with promoter-reporter plasmids containing GH response elements R34–35, R57–59, or R60–61 from the rat Igf1 gene (diagramed below) fused to rat Igf1 promoter 2 plus exon 2, and expression plasmids for the GH receptor and either Flag-tagged STAT5bWT, STAT5bA630P, or STAT5bF646S, and incubation with rat GH (40 nm) or vehicle for 18 h. The graph presents results of six independent duplicate experiments for each promoter plasmid (mean ± se; *, P < 0.001 for STAT5bWT vs. STAT5bA630P or STAT5bF646S without GH). Other P values are indicated (paired t test). Luciferase counts for R34–35 in the presence of STAT5bWT without GH ranged from 0.8 to 2.8 × 103 relative light units/sec.

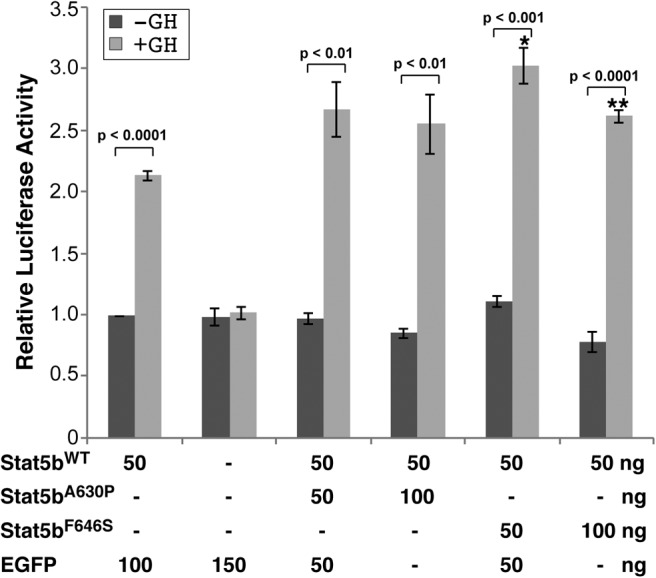

Neither STAT5bF646S nor STAT5bA630P have dominant-negative functions

We next tested the idea that STAT5bF646S or STAT5bA630P might inhibit the activity of STAT5bWT, a possibility that would be relevant to heterozygous individuals. Promoter-reporter gene experiments were performed with different combinations of WT and mutant STAT5b expression plasmids designed to mimic heterozygous subjects (1:1 plasmid DNA ratios) or to have more equivalent protein expression of both STAT5b molecules (1:2 DNA ratio, WT to mutant) (see Fig. 1B). Results demonstrate that neither mutant STAT5b protein reduced either the basal or GH-stimulated transcriptional activity of STAT5bWT (Fig. 3), and that STAT5bF646S even caused a small, statistically significant increase in the overall response to GH. Thus, neither STAT5bF646S nor STAT5bA630P has a dominant-negative function on actions of STAT5bWT.

Fig. 3.

Neither STAT5bF646S nor STAT5bA630P have dominant-negative functions. Results of luciferase assays after transient transfection of Cos-7 cells with a promoter-reporter plasmid containing GH response elements R34–35 from the rat Igf1 gene fused to rat Igf1 promoter 2 plus exon 2, and expression plasmids for the GH receptor and combinations of STAT5bWT and either STAT5bA630P, STAT5bF646S, or enhanced green fluorescent protein. Cells were incubated with rat GH (40 nm) or vehicle for 16–18 h. The graphs present results of four independent duplicate experiments with each combination of STAT5b expression plasmids (mean ± se; *, P < 0.01 or **, P < 0.001 for STAT5bWT vs. STAT5bF646S plus GH). Other P values are indicated (paired t test). Luciferase counts for R34–35 in the presence of STAT5bWT without GH ranged from 1.4 to 2.1 × 103 relative light units/sec.

STAT5bF646S accumulates in cells in insoluble protein aggregates

We previously found that STAT5bA630P formed protein aggregates in cells (24), and surmised, based on studies using fibroblasts from the individual with this amino acid substitution, that accumulation of STAT5bA630P in insoluble protein complexes is an inherent property of the mutant protein (24). To determine whether STAT5bF646S is also prone to aggregation, we looked for the protein in the insoluble fraction after extraction of transfected cells with buffer containing primarily nonionic detergents. Approximately half of STAT5bF646S and STAT5bA630P was located in this insoluble portion and could be solubilized fully only with ionic detergents (Fig. 4A). Complementary results were observed when transfected Cos-7 cells were evaluated by immunocytochemistry. In the absence of GH treatment STAT5bWT was found throughout the cytoplasm in a diffuse and uniform pattern, but both STAT5bF646S and STAT5bA630P were concentrated in multiple discrete cytoplasmic inclusions (Fig. 4B), which have been termed “aggresomes” when detected in cells expressing proteins that are prone to misfolding (38–40).

A higher resolution biochemical analysis of potential aggregation of STAT5b was performed using soluble cytoplasmic protein extracts, which were separated by nondenaturing gel electrophoresis. In the absence of GH, STAT5bWT was found as a monomer and formed tyrosine-phosphorylated dimers upon acute hormone treatment (Fig. 4C). By contrast, STAT5bF646S and STAT5bA630P were composed of multiple isoforms, including monomers, apparent dimers, and higher order species, with no change seen and little tyrosine phosphorylation induced after GH treatment (Fig. 4C). Thus, the two STAT5b amino acid substitution mutants each exhibit a propensity toward forming oligomeric complexes in cells that was not observed with STAT5bWT.

Analysis of the SH2 domain of STAT5bF646S

To understand how the STAT5bF646S mutation might perturb protein structure, we characterized isolated SH2 domains of WT and mutant human STAT5b after purification from E. coli, using CD and fluorescence spectroscopy. The far-UV CD spectrum of the A630P STAT5b SH2 domain demonstrated a slightly altered secondary structure relative to WT STAT5b, as evinced by a shoulder in the spectrum of the mutant protein at approximately 213 nm (Fig. 5A). By contrast, the spectrum of the F646S mutant closely resembled the WT SH2 domain (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the F646S substitution has a less significant effect on secondary structure than does the A630P mutation.

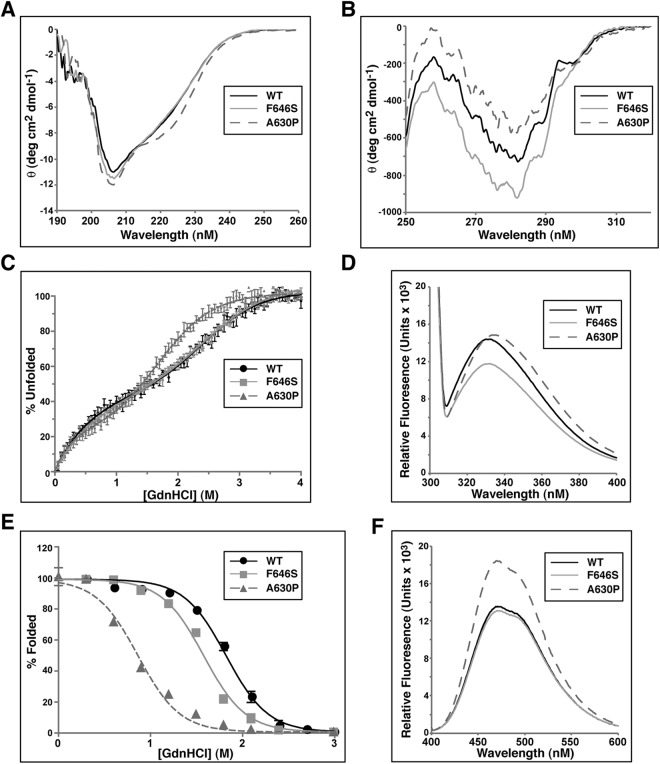

Fig. 5.

The SH2 domain of STAT5bF646S is less thermodynamically stable than the SH2 domain of STAT5bWT but more than STAT5bA630P. A, Far-UV CD spectra of folded STAT5b SH2 domains. The WT and F646S SH2 spectra are highly similar, whereas the A630P SH2 spectrum contains a marked shoulder at approximately 223 nm. B, Near-UV CD spectra of folded STAT5b SH2 domains. Both F646S and A630P mutants show a broad difference in overall negative ellipticity from the WT SH2 domain. C, Relative stability of SH2 domain secondary structure as a function of denaturant-induced unfolding (measured by CD at 222 nm). Individual data points are plotted (mean ± sem; n = 3 experiments). Folding-unfolding transitions appear to occur in at least two steps. D, Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence spectra. WT and A630P SH2 domains display similar fluorescence intensity (with a ∼2 nm red shift in the fluorescence maximum of A630P), while the F646S SH2 domain shows diminished intensity. E, Denaturant-induced equilibrium folding-unfolding of WT, F646S, and A630P SH2 domains monitored by intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence at 232 nm. Individual data points are plotted (mean ± sem; n = 3 experiments). Folding-unfolding transitions appear to occur in two steps. F, ANS-induced extrinsic fluorescence spectra.

Near-UV CD spectra revealed substantial differences among all three SH2 peptides in the environments of the side chains of aromatic residues, tryptophan, phenylalanine, and tyrosine, suggesting that both mutations may alter the packing of the tertiary structure of the SH2 domain (Fig. 5B). The differences in peak intensities between 260 and 290 nm may reflect changes in the relative mobility or polar environment of aromatic side chains, implying that each mutation may have broad effects on packing of the hydrophobic core of the SH2 domain (Fig. 5B).

The relative stability of secondary structure of WT and mutant SH2 domains toward unfolding was measured as a function of denaturant by CD at 222 nm. Folding-unfolding transitions for all three SH2 domains were cooperative and reversible (Fig. 5C), occurring in two steps, with the presence of a distinct folding intermediate. The A630P SH2 protein underwent unfolding at significantly lower concentrations of guanidine HCl than WT or F646S domains, the denaturation curves of which were indistinguishable. The midpoint of the first folding-unfolding transition for the A630P SH2 domain occurred at 0.5 m denaturant, and the second at 1.5 m, and unfolding was complete at 3 m guanidine HCl (Fig. 5C). In contrast, folding-unfolding transition midpoints were at 0.8 m and 2.5 m denaturant for both WT and F646S SH2 domains, and they maintained some secondary structure until addition of guanidine HCl to 3.5 m (Fig. 5C). Although the lack of a plateau under conditions of mild denaturation prevents obtaining accurate quantitative values for the relative changes in protein stability, these results nonetheless suggest that relative to the WT SH2 domain, the F646S mutation had little effect on thermodynamic stability of secondary structure, in contrast to the A630P substitution.

Tertiary structure of each SH2 domain was analyzed using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Peaks for both WT and F646S peptides were observed at approximately 332 nm whereas the A630P mutant was slightly red-shifted with a peak at about 334 nm (Fig. 5D). In contrast, the magnitude of tryptophan fluorescence of the F646S SH2 domain was diminished relative to WT or A630P peptides, suggesting either quenching or a change in the electronic environment of the two tryptophan residues (Fig. 5D).

Overall thermodynamic stability of STAT5b SH2 domain tertiary packing was evaluated by analyzing denaturant-induced unfolding under equilibrium conditions, as measured by tryptophan fluorescence at 332 nm. All three SH2 domains underwent reversible folding-unfolding transitions (Fig. 5E). In contrast to measurements of secondary structural stability by CD, the F646S SH2 domain was less stable than the WT protein, as evidenced by a midpoint of unfolding at 1.6 m guanidine HCl, vs. 1.9 m for the WT SH2 domain. Under the same assay conditions, the A630P mutant was far less stable, because its midpoint transition was reached at 0.9 m guanidine HCl (Fig. 5E). Thus, although the F646S substitution reduces the thermodynamic stability of the SH2 domain, the destabilizing effects are not as significant as seen with the A630P mutation.

The presence of potential solvent-exposed hydrophobic surfaces within the two mutant SH2 domains was examined by binding of the dye ANS to folded peptides. Enhanced binding of ANS to exposed hydrophobic surfaces yielded a substantial increase in fluorescence intensity for the A630P SH2 domain (Fig. 5F, and Ref. 24). By contrast, the ANS fluorescence spectrum for the F646S mutant was nearly identical to that of the WT peptide (Fig. 5F).

Taken together, these results show that the F646S mutation causes minimal alterations in secondary structure and moderate changes in the tertiary structure of the isolated STAT5b SH2 domain that are less severe than those seen with the A630P amino acid substitution. The main effect of the F646S mutation is to alter tertiary packing and reduce thermodynamic stability of the SH2 domain (Fig. 5E), an interpretation supported by increased negative ellipticity of aromatic residues seen in near-UV CD spectra (Fig. 5B), and by diminished intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (Fig. 5D).

Homology modeling and structural analysis of WT and mutant STAT5b SH2 domains

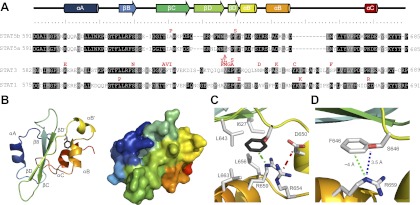

The structure of mammalian STAT SH2 domains is highly conserved and is composed of a three-stranded β-sheet sandwiched between two sets of α-helices (Fig. 6A). To more fully understand the effects of A630P and F646S mutations on human STAT5b SH2 domains, homology models were prepared using the structures of STAT5a or STAT1 as reference models (PDB accession codes 1Y1U and 1YVL, respectively) (31, 32). On the basis of the homology model, A630P is located in the middle of the second strand of the β-sheet (βC) (24) whereas F646 maps near the end of the third β-sheet (βD′) (Fig. 6B). Although A630 does not appear to have many significant side-chain interactions, the mutation to a proline at this location is likely to dramatically alter the peptide backbone and has the effect of distorting βC in a manner that may disrupt interactions between it and both βB and βD/βD′. This destabilizing effect readily explains the diminished solubility of full-length STAT5bA630P, as well as its reduced activity, as noted previously (24).

Fig. 6.

Mutations in STAT SH2 domains have diverse effects on structure and function. A, Sequence alignment of SH2 domains from human STAT5b, STAT5a, STAT1, and STAT3. Identical amino acids in all four STATs are shaded in black and similar residues are shaded in gray. Secondary structural features are displayed above the alignment; natural inactivating amino acid substitutions are indicated in red above each STAT. B, Homology model of the human STAT5b SH2 domain based on the X-ray crystal structures of STAT1 (PDB 1YVL) and STAT5a (PDB 1Y1U). The left panel shows a ribbon diagram, and the right panel shows a space-filling model. Color coding corresponds to the secondary structural features depicted in panel A. In the left panel, the F646 phenyl ring is highlighted in gray, and the S substitution overlaid (CPK coloring). C, Close-up of the region around residue 646 (F646 in dark gray, S646 hydroxyl in red). Note the four hydrophobic residues (I627, L643, L656, L663), the nearby salt bridge between D650 and R654 on helices αΒ′ and αΒ, respectively (hatched red line), and the charged R659, shown to interact directly with the phenyl ring of F646 (hatched green line). D, Interactions between residues 646 and R659, demonstrating the ability of S646 to form a hydrogen bond with R659 (blue dotted line) to replace the ion-bond found with the WT F residue (green dotted line).

F646 forms the core of a largely hydrophobic pocket bounded by βD/βD′ and the second set of α-helices (αB/αB′) (Fig. 6, B and C). Tertiary structure appears to be stabilized by hydrophobic interactions between F646 and nearby nonpolar residues (I627, L643, L656, L663), and possibly by a salt bridge between D650 and R654, as well as by a cation-pi bond between the phenyl ring of F646 and R659 (Fig. 6C). The F646S mutation replaces the phenyl side chain with a considerably smaller, more polar hydroxyl group, which is predicted to disrupt van der Waals interactions with nearby nonpolar side chains and the salt bridge-stabilizing helices αB and αB′, presumably resulting in an overall destabilizing effect on the entire STAT5bF646S molecule. Although the ion-pi bond with R659 that stabilizes the association of βD/βD′ with βC and αB′ would be abolished in this mutant, the model suggests that the geometries are favorable for formation of a new hydrogen bond between the S646 hydroxyl and R659 (Fig. 6D), which may moderate other deleterious structural effects of the amino acid substitution.

Discussion

Multiple observations provide strong evidence for the idea that STAT5b plays a key role in the GH-IGF-I-growth pathway. Targeted knockout of Stat5b in mice causes diminished postnatal growth (10, 11), and biochemical studies have found that Stat5b mediates GH-activated IGF-I gene transcription (reviewed in Ref. 37). In humans, seven homozygous inactivating STAT5B mutations have been described in 10 patients with profound growth deficiency and markedly reduced IGF-I expression (7, 22). Five of the seven STAT5B mutations are nucleotide alterations that introduce stop codons into the coding region of STAT5B mRNA, and it is likely that the affected individuals lack full-length STAT5b protein (7, 22). We previously found that fibroblasts from the first described patient carrying an amino acid substitution within the SH2 domain of the protein (A630P) produced a mutant STAT5b molecule (14, 24). Not only was this protein transcriptionally inactive, but it also was prone to aggregation and accumulated in cells within cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (24). In addition, because its isolated SH2 domain formed aggregates in solution, we proposed that this subject had a disorder of protein folding, in which a misfolded SH2 domain caused functional STAT5b deficiency and through its protein aggregation contributed to other secondary abnormalities resulting from inhibition of proteosome function (24).

Here we have characterized the second identified homozygous amino acid substitution mutation in human STAT5b, which changes phenylalanine 646 to serine, also within the SH2 domain, and have compared its biochemical, biophysical, and structural properties to both STAT5bWT and STAT5bA630P. Like human STAT5bA630P, STAT5bF646S is prone to aggregation, as evidenced by its detection in the insoluble fraction, the presence of dimers and higher-order proto-aggregates in the soluble fraction, independent of GH treatment, and its propensity toward forming insoluble cytoplasmic inclusion bodies in cells. Unlike STAT5bA630P, which showed minimal GH-induced tyrosine phosphorylation, and no transcriptional activity, soluble STAT5bF646S was capable of being tyrosine phosphorylated by the activated GH receptor, although to a much lesser extent than STAT5bWT, and was able to function as a GH-stimulated transcription factor, although with considerably less potency than STAT5bWT. In addition, even though its isolated SH2 domain showed smaller structural perturbations than did the A630P SH2 protein, in the context of the full-length molecule it is likely that the STAT5bF646S SH2 domain reduces recognition of selected phosphotyrosine substrates. Support for this idea comes from the crystal structures of STAT1 bound to phosphopeptides [PDB accession numbers 1YVL and 1BF5 (31, 51)]. Y634, the equivalent residue to F646 in human STAT1 (Fig. 6A), is found in close proximity to the phosphotyrosine [∼10 Å from the pY side chain and within 3–4 Å of side chains of residues COOH terminal to the pY (31, 51)]. If the F646S mutation has a distorting effect on tertiary packing of this region of the protein (Fig. 5, B and D, and Fig. 6, C and D), it is likely that the SH2 domain-phosphotyrosine interface would be disrupted, which could account for the diminished dimerization, DNA-binding, and, transcriptional activity compared with STAT5bWT and would explain the inability of STAT5bF646S to sustain target gene transcription in vivo, as evidenced by the significant growth failure and other medical problems in the patient (23).

Remarkably, mutations have been found within the SH2 domains of two other STATs in human diseases (41). The immunodeficiency syndrome termed “Mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease” is caused by defects in the interferon γ signaling pathway (41), and heterozygous mutations have been mapped in individual patients to the STAT1 gene (42), including three subjects with single amino acid substitutions in the COOH-terminal part of the SH2 domain, which change lysine 637 to glutamic acid, methionine 654 to lysine, or lysine 673 to arginine (42–44) (Fig. 6A). When expressed in cultured cells, STAT1M654K is unable to be tyrosine phosphorylated in response to treatment with interferon γ, and when coexpressed with STAT1WT, blocks its transcriptional function (42). Although STAT1K637E and STAT1K673R can be tyrosine phosphorylated in cells after exposure to interferon γ, they each also inhibit the transcriptional actions of STAT1WT (44). Taken together, these observations provide biochemical evidence supporting the dominant-negative function of each of these heterozygous mutant STAT1 proteins in vivo (42, 44).

Heterozygous inactivating mutations in the STAT3 gene also have been found in the majority of families and individuals with hyper-IgE syndrome, an immune deficiency disorder that exhibits clinical manifestations of eczema, staphylococcal infections of the skin and lungs, elevated IgE levels, and skeletal abnormalities (41). Most of the mutations in the STAT3 gene in these patients lead to amino acid substitutions, and have been shown to cluster within the DNA binding region or the SH2 domain of the protein (45–49) (Fig. 6A). Limited analyses have demonstrated that the SH2 domain amino acid substitutions impair tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 in response to IL6 or epidermal growth factor (47), reduce its DNA binding and transcriptional activity, and act as dominant interfering mutations by blocking the function of STAT3WT through heterodimerization (49). In contrast to observations made with STAT1 and STAT3 SH2 domain amino acid substitution mutants, neither STAT5bA630P nor STAT5bF646S exhibited a dominant-negative function, because coexpression with STAT5bWT did not inhibit either basal or GH-stimulated transcriptional activity (Fig. 3).

Several somatic activating mutations also have been identified within the SH2 domain of STAT3 associated with the large granular subtype of lymphocytic leukemia (50). Each amino acid substitution identified in these patients appears to cause increased tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation of the mutant STAT3 molecule and leads to enhanced transcriptional activity compared with STAT3WT (50). Although these observations reinforce the central role of the SH2 domain in controlling STAT activation, the molecular basis by which these mutations bypass normal regulatory pathways remains elusive, because, to date, no studies have been performed on the biochemical or biophysical characteristics of any SH2 domain mutation in STAT1 or STAT3.

The ubiquitin-proteasome system normally digests damaged or misfolded proteins and thus serves to protect cells from toxic effects of protein aggregation (38). However, aggregated proteins are not degraded efficiently and may accumulate, forming structures termed “aggresomes” or “inclusion bodies,” which can interfere with ubiquitin-proteasome function (38–40), as we showed previously for STAT5bA630P (24). Because overexpressed STAT5bF646S appears to form protein aggregates in transfected cells similar to STAT5bA630P, this defect also may contribute to secondary abnormalities resulting from inhibition of proteosome function, although we have not had the opportunity to confirm this supposition in cells derived from the patient.

Because the SH2 segments of STAT5b, STAT1, and STAT3 are structurally similar (18, 31, 32, 51), it is likely that some of inactivating mutations found in these latter proteins also may promote aggregation (Fig. 5A). Taken together, our results not only support the concept of STAT deficiency syndromes caused by protein misfolding, but suggest that investigation into the biochemical and biophysical properties of these mutations could generate insights with the potential to shape fruitful corrective therapeutic interventions in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK063073 (to P.R.), National Science Foundation Grant 0746589 (to U.S.), and a grant from the Medical Research Foundation of Oregon (to V.H.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- ANS

- 1 Anilino-8-naphtalene sulphonic acid

- CD

- circular dichroism

- JAK

- Janus family of tyrosine kinases

- SH2

- Src homology-2

- STAT

- signal transducer and activator of transcription

- WT

- wild type.

References

- 1. Lanning NJ, Carter-Su C. 2006. Recent advances in growth hormone signaling. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 7:225–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rosenfeld RG, Hwa V. 2009. The growth hormone cascade and its role in mammalian growth. Horm Res 71(Suppl 2):36–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenfeld RG. 2010. Endocrinology of growth. Nestle Nutr Workshop Ser Pediatr Program 65:225–234; discussion 234–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Backeljauw PF, Chernausek SD. 2012. The insulin-like growth factors and growth disorders of childhood. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 41:265–282, v [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ranke MB. 2010. Clinical considerations in using growth hormone therapy in growth hormone deficiency. Endocr Dev 18:83–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Laron Z. 2011. Growth hormone therapy: emerging dilemmas. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 8:364–373 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hwa V, Nadeau K, Wit JM, Rosenfeld RG. 2011. STAT5b deficiency: lessons from STAT5b gene mutations. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 25:61–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wit JM, van Duyvenvoorde HA, Scheltinga SA, de Bruin S, Hafkenscheid L, Kant SG, Ruivenkamp CA, Gijsbers AC, van Doorn J, Feigerlova E, Noordam C, Walenkamp MJ, Claahsen-van de Grinten H, Stouthart P, Bonapart IE, Pereira AM, Gosen J, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Hwa V, Breuning MH, Domené HM, Oostdijk W, Losekoot M. 2012. Genetic analysis of short children with apparent growth hormone insensitivity. Horm Res Paediatr 77:320–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Waters MJ, Hoang HN, Fairlie DP, Pelekanos RA, Brown RJ. 2006. New insights into growth hormone action. J Mol Endocrinol 36:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Teglund S, McKay C, Schuetz E, van Deursen JM, Stravopodis D, Wang D, Brown M, Bodner S, Grosveld G, Ihle JN. 1998. Stat5a and Stat5b proteins have essential and nonessential, or redundant, roles in cytokine responses. Cell 93:841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Udy GB, Towers RP, Snell RG, Wilkins RJ, Park SH, Ram PA, Waxman DJ, Davey HW. 1997. Requirement of STAT5b for sexual dimorphism of body growth rates and liver gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:7239–7244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tronche F, Opherk C, Moriggl R, Kellendonk C, Reimann A, Schwake L, Reichardt HM, Stangl K, Gau D, Hoeflich A, Beug H, Schmid W, Schütz G. 2004. Glucocorticoid receptor function in hepatocytes is essential to promote postnatal body growth. Genes Dev 18:492–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Woelfle J, Billiard J, Rotwein P. 2003. Acute control of insulin-like growth factor-I gene transcription by growth hormone through Stat5b. J Biol Chem 278:22696–22702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kofoed EM, Hwa V, Little B, Woods KA, Buckway CK, Tsubaki J, Pratt KL, Bezrodnik L, Jasper H, Tepper A, Heinrich JJ, Rosenfeld RG. 2003. Growth hormone insensitivity associated with a STAT5b mutation. N Engl J Med 349:1139–1147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rowland JE, Lichanska AM, Kerr LM, White M, d'Aniello EM, Maher SL, Brown R, Teasdale RD, Noakes PG, Waters MJ. 2005. In vivo analysis of growth hormone receptor signaling domains and their associated transcripts. Mol Cell Biol 25:66–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schindler C, Shuai K, Prezioso VR, Darnell JE., Jr 1992. Interferon-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of a latent cytoplasmic transcription factor. Science 257:809–813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Shuai K, Schindler C, Prezioso VR, Darnell JE., Jr 1992. Activation of transcription by IFN-gamma: tyrosine phosphorylation of a 91-kD DNA binding protein. Science 258:1808–1812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Levy DE, Darnell JE., Jr 2002. Stats: transcriptional control and biological impact. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3:651–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hennighausen L, Robinson GW. 2008. Interpretation of cytokine signaling through the transcription factors STAT5A and STAT5B. Genes Dev 22:711–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schindler C, Plumlee C. 2008. Inteferons pen the JAK-STAT pathway. Semin Cell Dev Biol 19:311–318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yu H, Pardoll D, Jove R. 2009. STATs in cancer inflammation and immunity: a leading role for STAT3. Nat Rev Cancer 9:798–809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nadeau K, Hwa V, Rosenfeld RG. 2011. STAT5b deficiency: an unsuspected cause of growth failure, immunodeficiency, and severe pulmonary disease. J Pediatr 158:701–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Scaglia PA, Martínez AS, Feigerlová E, Bezrodnik L, Gaillard MI, Di Giovanni D, Ballerini MG, Jasper HG, Heinrich JJ, Fang P, Domené HM, Rosenfeld RG, Hwa V. 2012. A novel missense mutation in the SH2 domain of the STAT5B gene results in a transcriptionally inactive STAT5b associated with severe IGF-I deficiency, immune dysfunction, and lack of pulmonary disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97:E830–E839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chia DJ, Subbian E, Buck TM, Hwa V, Rosenfeld RG, Skach WR, Shinde U, Rotwein P. 2006. Aberrant folding of a mutant Stat5b causes growth hormone insensitivity and proteasomal dysfunction. J Biol Chem 281:6552–6558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Woelfle J, Chia DJ, Rotwein P. 2003. Mechanisms of growth hormone (GH) action. Identification of conserved Stat5 binding sites that mediate GH-induced insulin-like growth factor-I gene activation. J Biol Chem 278:51261–51266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chia DJ, Varco-Merth B, Rotwein P. 2010. Dispersed chromosomal Stat5b-binding elements mediate growth hormone-activated insulin-like growth factor-I gene transcription. J Biol Chem 285:17636–17647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chia DJ, Ono M, Woelfle J, Schlesinger-Massart M, Jiang H, Rotwein P. 2006. Characterization of distinct Stat5b binding sites that mediate growth hormone-stimulated IGF-I gene transcription. J Biol Chem 281:3190–3197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen H, Sun H, You F, Sun W, Zhou X, Chen L, Yang J, Wang Y, Tang H, Guan Y, Xia W, Gu J, Ishikawa H, Gutman D, Barber G, Qin Z, Jiang Z. 2011. Activation of STAT6 by STING is critical for antiviral innate immunity. Cell 147:436–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Subbian E, Yabuta Y, Shinde U. 2004. Positive selection dictates the choice between kinetic and thermodynamic protein folding and stability in subtilases. Biochemistry 43:14348–14360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, Valentin F, Wallace IM, Wilm A, Lopez R, Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG. 2007. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23:2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mao X, Ren Z, Parker GN, Sondermann H, Pastorello MA, Wang W, McMurray JS, Demeler B, Darnell JE, Jr, Chen X. 2005. Structural bases of unphosphorylated STAT1 association and receptor binding. Mol Cell 17:761–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Neculai D, Neculai AM, Verrier S, Straub K, Klumpp K, Pfitzner E, Becker S. 2005. Structure of the unphosphorylated STAT5a dimer. J Biol Chem 280:40782–40787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Peitsch MC. 1996. ProMod and Swiss-Model: Internet-based tools for automated comparative protein modelling. Biochem Soc Trans 24:274–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. 2006. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22:195–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kiefer F, Arnold K, Künzli M, Bordoli L, Schwede T. 2009. The SWISS-MODEL Repository and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res 37:D387–D392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guex N, Peitsch MC. 1997. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rotwein P. 2012. Mapping the growth hormone-Stat5b-IGF-I transcriptional circuit. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23:186–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kopito RR. 2000. Aggresomes, inclusion bodies and protein aggregation. Trends Cell Biol 10:524–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chin LS, Olzmann JA, Li L. 2010. Parkin-mediated ubiquitin signalling in aggresome formation and autophagy. Biochem Soc Trans 38:144–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olzmann JA, Li L, Chin LS. 2008. Aggresome formation and neurodegenerative diseases: therapeutic implications. Curr Med Chem 15:47–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Casanova JL, Holland SM, Notarangelo LD. 2012. Inborn errors of human JAKs and STATs. Immunity 36:515–528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sampaio EP, Bax HI, Hsu AP, Kristosturyan E, Pechacek J, Chandrasekaran P, Paulson ML, Dias DL, Spalding C, Uzel G, Ding L, McFarland E, Holland SM. 2012. A novel STAT1 mutation associated with disseminated mycobacterial disease. J Clin Immunol 32:681–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kristensen IA, Veirum JE, Møller BK, Christiansen M. 2011. Novel STAT1 alleles in a patient with impaired resistance to mycobacteria. J Clin Immunol 31:265–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tsumura M, Okada S, Sakai H, Yasunaga S, Ohtsubo M, Murata T, Obata H, Yasumi T, Kong XF, Abhyankar A, Heike T, Nakahata T, Nishikomori R, Al-Muhsen S, Boisson-Dupuis S, Casanova JL, Alzahrani M, Shehri MA, Elghazali G, Takihara Y, Kobayashi M. 2012. Dominant-negative STAT1 SH2 domain mutations in unrelated patients with mendelian susceptibility to mycobacterial disease. Hum Mutat 33:1377–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, Hsu AP, Uzel G, Brodsky N, Freeman AF, Demidowich A, Davis J, Turner ML, Anderson VL, Darnell DN, Welch PA, Kuhns DB, Frucht DM, Malech HL, Gallin JI, Kobayashi SD, Whitney AR, Voyich JM, Musser JM, Woellner C, Schäffer AA, Puck JM, Grimbacher B. 2007. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N Engl J Med 357:1608–1619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Minegishi Y, Saito M, Tsuchiya S, Tsuge I, Takada H, Hara T, Kawamura N, Ariga T, Pasic S, Stojkovic O, Metin A, Karasuyama H. 2007. Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature 448:1058–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Renner ED, Rylaarsdam S, Anover-Sombke S, Rack AL, Reichenbach J, Carey JC, Zhu Q, Jansson AF, Barboza J, Schimke LF, Leppert MF, Getz MM, Seger RA, Hill HR, Belohradsky BH, Torgerson TR, Ochs HD. 2008. Novel signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) mutations, reduced T(H)17 cell numbers, and variably defective STAT3 phosphorylation in hyper-IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 122:181–187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Woellner C, Gertz EM, Schäffer AA, Lagos M, Perro M, Glocker EO, Pietrogrande MC, Cossu F, Franco JL, Matamoros N, Pietrucha B, Heropolitańska-Pliszka E, Yeganeh M, Moin M, Español T, Ehl S, Gennery AR, Abinun M, Breborowicz A, Niehues T, Kilic SS, Junker A, Turvey SE, Plebani A, Sánchez B, et al. 2010. Mutations in STAT3 and diagnostic guidelines for hyper-IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 125:424–432.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. He J, Shi J, Xu X, Zhang W, Wang Y, Chen X, Du Y, Zhu N, Zhang J, Wang Q, Yang J. 2012. STAT3 mutations correlated with hyper-IgE syndrome lead to blockage of IL-6/STAT3 signalling pathway. J Biosci 37:243–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Koskela HL, Eldfors S, Ellonen P, van Adrichem AJ, Kuusanmäki H, Andersson EI, Lagström S, Clemente MJ, Olson T, Jalkanen SE, Majumder MM, Almusa H, Edgren H, Lepistö M, Mattila P, Guinta K, Koistinen P, Kuittinen T, Penttinen K, Parsons A, Knowles J, Saarela J, Wennerberg K, Kallioniemi O, Porkka K, et al. 2012. Somatic STAT3 mutations in large granular lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med 366:1905–1913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen X, Vinkemeier U, Zhao Y, Jeruzalmi D, Darnell JE, Jr, Kuriyan J. 1998. Crystal structure of a tyrosine phosphorylated STAT-1 dimer bound to DNA. Cell 93:827–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]