Abstract

Aim:

The combined hepatoprotective effect of Bi-herbal ethanolic extract (BHEE) was evaluated against paracetamol induced hepatic damage in albino rats.

Materials and Methods:

Liver function tests and biochemical parameters were estimated using standard kits. Livers were quickly removed and fixed in 10% formalin and subjected to histopathological studies.

Results:

Ethanolic extract from the leaves of Aerva lanata and leaves of Achyranthes aspera at a dose level of 200 mg/kg, 400mg/kg body weight was administered orally once for 3 days. Substantially elevated serum marker enzymes such as SGOT, SGPT, ALP, due to paracetamol treatment were restored towards normal. Biochemical parameters like total protein, total bilirubin, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and urea were also restored towards normal levels. In addition, BHEE significantly decreased the liver weight of paracetamol intoxicated rats. Silymarin at a dose level of 25 mg/kg used as a standard reference also exhibited significant hepatoprotective activity against paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity.

Conclusion:

The results of this study strongly indicate that BHEE has got a potent hepatoprotective action against paracetamol induced hepatic damage in rats.

Keywords: Biherbal ethanolic extract, heptoprotective, paracetamol, serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase

INTRODUCTION

The liver is of vital importance in intermediary metabolism and in detoxification and elimination of toxic substances. The liver is often affected by a multitude of environmental pollutants and drugs, all of which place a burden on this vital organ and can damage and weaken it, eventually leading to diseases like hepatitis or cirrhosis.[1] Paracetamol's hepatotoxicity is caused by its reactive metabolite N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI), which causes oxidative stress and glutathione (GSH) depletion. Paracetamol toxicity is due to the formation of toxic metabolites when a part of it is metabolized by cytochrome P450.[2] Introduction of cytochrome or depletion of hepatic glutathione is a prerequisite for paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity.[3,4,5] In spite of tremendous strides in modern medicine, the treatment of liver disorders isinadequate and many formulations containing herbal extracts are used for regeneration of hepatic cells and for protection of the liver against damage.[6]

Hepatic damage is associated with distortion of its metabolic functions and it is still a major health problem.[7] Unfortunately many synthetic drugs used in the treatment of liver diseases are inadequate and also cause serious side effects.[8] In view of severe undesirable side effects of synthetic agents, there is growing interest in evaluating traditional herbal medicines that are claimed to possess hepatoprotective activity. A single drug cannot be effective for all types of severe liver diseases. Therefore, an effective formulation using indigenous medicinal plants has to be developed with proper pharmacological experiments and clinical trials.[9] Considering the above limitations, a biherbal ethanolic extract (BHEE) made up of equal quantities of leaves of Aerva lanata and leaves of Achyranthes aspera was subjected to various assays. In order to evaluate its hepatoprotective effect, an extract from the mixture of these herbs was tested against paracetamol-induced toxicity in albino rats.

A. aspera (Amaranthaceae) is an annual stiff erect herb found commonly as a weed throughout India and used by the traditional healers for the treatment of fever, dysentery, and diabetes.[10] A. lanata Linn (Amaranthaceae) is a herbaceous perennial weed growing wild in the hot region of India. A. lanata has been claimed to be useful as diuretic, antidiabetic, expectorant, and hepatoprotective in traditional system of medicine.[11] The present study investigates the activity of the BHEE against paracetamol-induced toxicity in comparison with silymarin a well-known antihepatotoxic agent.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant material

The fresh leaves of A. aspera and leaves of A. lanata were collected from Dr. Ammani Ayurvedic Hospital and Research Centre, Eluru, West Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh, India, and were authenticated by Dr. S. Mahesh Venkata Govindnath at the same center. A voucher specimen (AAHSC-89543 and AAHSC-89551) was preserved at Dr. Ammani Ayurvedic Hospital and Research Centre for future reference.

Preparation of the extract

The leaves of A. aspera (1 kg) and leaves of A. lanata (1 kg) each, were shade dried and pulverized into a coarse powder and extracted with 90% ethanol in Soxhlet apparatus at 80°C for 18 h separately. Equal quantities of the powder was passed through a 40-mesh sieve and exhaustively extracted with 90% (v/v) ethanol in Soxhlet apparatus at 80°C for 18 h.[6] The individual extracts and biherbal ethanolic extract were evaporated under pressure until all the solvent had been removed. Further removal of the water was carried out by freeze drying to give an extract sample with the yield of 14.2% (w/w). The extracts were stored in refrigerator, and weighed amount was dissolved in 10 mL of distilled water and used for present investigation.

Animals

Adult albino male rats of Wistar strain, weighing 150-175 g were used in the pharmacologic and toxicologic studies. The in bred animals were purchased from animal house in Mahaveer Enterprises, Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh, India. Animals were maintained under standard laboratory conditions at 25°C±2°C relative humidity 50% ± 15% and normal photoperiod (12:12 h dark:light cycle) were used for the experiment. Commercial pellet diet (Rayon′s Biotechnology Pvt Ltd, India) and water were provided ad libitum. The experimental protocol has been approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee and by the Animal Regulatory Body of the Government (Regd.No:439/01/a/CPCSEA).

Experimental design

A total of 42 animals were equally divided into 7 groups of 6 each. Extracts were administered orally to the rats. Group I served as normal control, which received 0.5% carboxy methyl cellulose (CMC) solution (1 mL/kg) once daily for 3 days. Group II served as paracetamol control, which received paracetamol (3 g/kg) as a single dose on day 3.

Group III served as reference control and received silymarin (25 mg/kg) once daily for 3 days. Group IV received alcoholic extract of A. aspera (400 mg/kg) once daily for 3 days. Group V received A. lanata (400 mg/kg) once daily for 3 days. Group VI received biherbal alcoholic extract of A. lanata and A. aspera (200 mg/kg) once daily for 3 days. Group VII received biherbal alcoholic extract of A. lanata and A. aspera (400 mg/kg) once daily for 3 days. All groups except Group I received paracetamol (3 g/kg) as a single dose after 30 min of 3-day treatment of the herbal drug. All the test drugs and paracetamol were administered orally by suspending in 0.5% CMC solution. After 48 h of paracetamol feeding, blood was collected by direct cardiac puncture under light ether anesthesia and serum was separated for the assessment of liver function parameters and for assessment of biochemical parameters.

Assessment of liver function parameters

At the end of the experimental period, animals were sacrificed by cervical decapitation under mild ketamine anesthesia, blood was collected and the serum was separated by centrifuging at 300 rpm for 10 min. The collected serum was used for the assay of marker enzymes. The serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (SGOT) and serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase (SGPT) were estimated by the method of Reitman and Frankel.[12] Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) was determined by the method of Kind and King.[13]

Assessment of biochemical parameters

The biochemical parameters, such as total protein was estimated by the method of Gornall.[14] The total cholesterol was estimated by the method of Wybenga.[15] The total bilirubin was estimated by Method of Malloy and Evelyn.[16] Triglycerides were estimated by the method of Fossati and Lorenzo[17] and urea concentration was determined by the method of Bousquet.[18] Immediately after sacrificing the animal, the liver was excised from the animals, washed in ice-cold saline, and the weight of the liver was recorded.

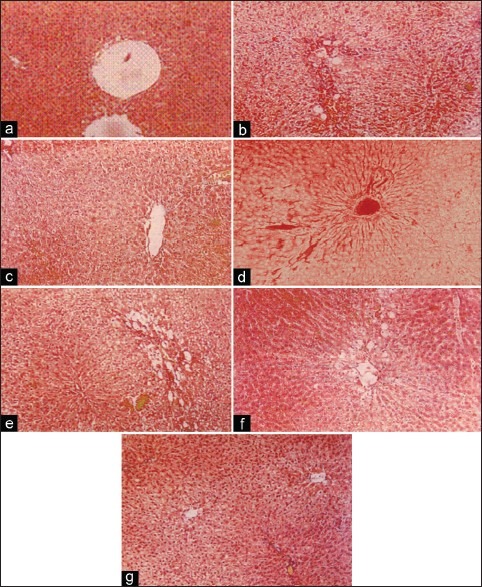

Histological studies

Livers were quickly removed and fixed in 10% formalin, dehydrated in gradual ethanol (50%-100%), cleared in xylene and embedded in paraffin. Sections (4-5 μm thick) were prepared and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin dye for photomicroscopic observations of the liver histologic architecture of the control and treated rats.

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (S.D). Differences in liver function parameters and biochemical parameters were determined by factorial one-way ANOVA. Individual groups were compared using Tukey′s test. Differences with P<0.001 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

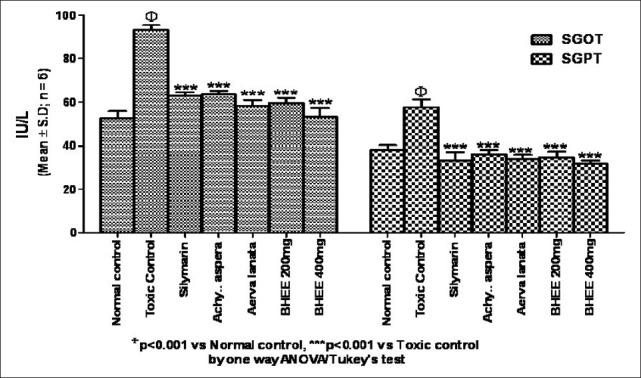

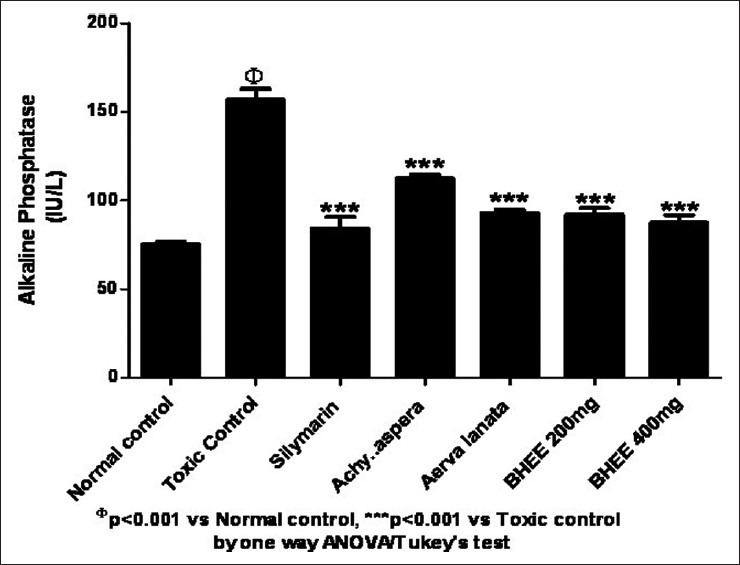

A significant increase in SGOT (93.17 ± 2.23) and SGPT (57.50 ± 3.62) levels was seen in Group II paracetamol-intoxicated animals. These enzymes were reduced to near normal levels (34.83 ± 2.48) and (31.67 ± 1.75), respectively, in groups VI and VII animals (P<0.001) [Figure 1]. Similarly Figure 2 shows that elevated ALP (157.00 ± 5.80) enzyme levels in Group II paracetamol-intoxicated animals were also decreased to (92.17 ± 3.54) and (87.50 ± 4.04) in Group VI and VII treated rats [Table 1].

Figure 1.

Effect of biherbal ethanolic extract on serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase and serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

Figure 2.

Effect of biherbal ethanolic extract on alkaline phosphatase against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

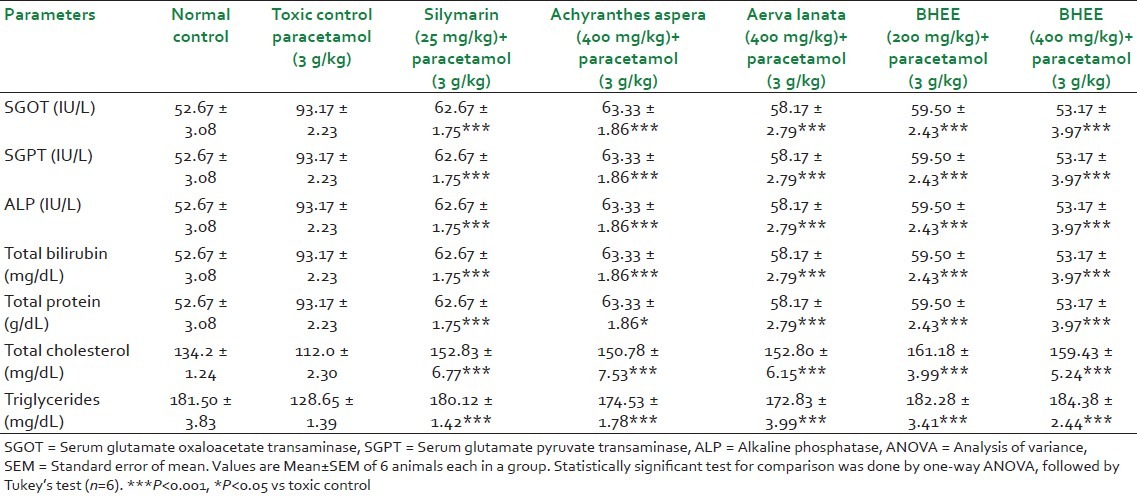

Table 1.

Effect of biherbal alcoholic extract on liver function and biochemical parameters under different experimental conditions

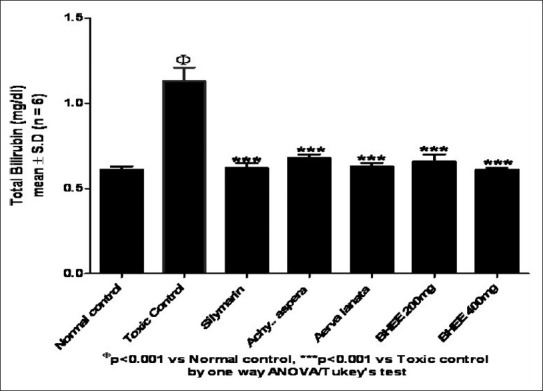

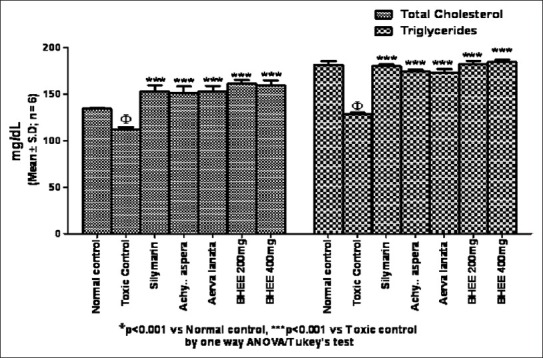

In the present investigation, a significant reduction in the liver weight (P<0.001) was seen in Group VI and VII BHEE-treated animals when compared with that of Group II paracetamol-intoxicated and Group IV and V animals. Table 1 and Figure 3 depicts that the biochemical parameters, such as serum bilirubin (0.62 ± 0.01, 0.66 ± 0.04) and urea (24.57 ± 0.67, 22.28 ± 0.91) levels were also decreased significantly in Group VI and VII BHEE (at a dose level of 200 and 400 mg/kg body weight) treated animals (P<0.001) when compared with the paracetamol-intoxicated Group II animals, which displayed the total bilirubin (1.13 ± 0.08) and urea (39.72 ± 0.97), respectively. Table 1, [Figures 4 and 5] show that in Group VI and VII there was a significant increase in total protein (5.75 ± 0.16, 6.02 ± 0.28), total cholesterol (161.18 ± 3.99, 159.43 ± 5.24), and triglyceride (182.28 ± 3.41, 184.38 ± 2.44) levels when compared with the Group II paracetamol-intoxicated animals, which displayed the total protein (5.10 ± 0.13), total cholesterol (112.0 ± 2.30), and triglyceride (128.65 ± 1.39), respectively. Group comparison between Group I and groups VI, VII shows no significant variation in liver weight and biochemical parameter levels, which indicates no appreciable adverse effect due to the administration of Tween 80 and BHEE alone [Figures 4 and 5]. Group comparison between Group III and groups VI, VII shows no significant variation in these parameters indicating that BHEE has got the same effect as that of the silymarin, which was considered as the positive control in this study.

Figure 3.

Effect of biherbal ethanolic extract on total bilirubin against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

Figure 4.

Effect of biherbal ethanolic extract on total cholesterol and tryglycerides against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats

Figure 5.

Effect of biherbal ethanolic extract on total protein against paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity in rats

Group comparison between Group I control rats and the animals of groups VI and VII, which received only BHEE shows no significant variation in the marker enzyme levels indicating no adverse side effects due to the administration of Tween 80 and BHEE alone. All the parameters were under normal limits in the group III animals which acted as a positive control, and were intoxicated by paracetamol and treated by silymarin.

DISCUSSION

Liver injuries induced by paracetamol is one of the best characterized system of xenobiotic-induced hepatotoxicity and commonly used model for the screening of hepatoprotective activities of drugs.[19] To the best of our knowledge, for the first time we report that administration of BHEE ameliorated paracetamol induced acute liver injury in rats, as evidenced by both histologic findings and biochemical findings. Similar protective effects were also observed in rats receiving silymarin, which was used as a positive control, although the mechanism of action for these effects may not be the same.

Silymarin is a polyphenolic flavonoid isolated from the fruit and seeds of the milk thistle (Silybum marianum).[20] Various studies indicate that silymarin exhibits strong antioxidant activity[21] and shows protective effects against hepatic toxicity induced by a wide variety of agents by inhibiting lipid peroxidation.[22,23]

Hepatotoxic drugs, such as paracetamol, are known to cause marked elevation in serum level of enzymes, such as SGOT, SGPT, ALP, and bilirubin, indicating significant hepatocellular injury. Raised activity of serum transaminases in intoxicated rats, as observed in the present study, can be attributed to the damaged structural integrity of the liver because these are cytoplasmic in nature and are released into the circulation after cellular damage. Decrease in total serum protein was observed in rats treated with paracetamol and may be associated with the decrease in the number of hepatocytes, which in turn may result in the decreased hepatic capacity to synthesize protein and consequently decrease liver weight.

In the present study it was noted that the administration of paracetamol decreased the levels of total protein, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. These parameters were maintained at normal levels in the BHEE-treated animals. BHEE treatment showed a protection against the injurious effects of paracetamol that may result from the interference with cytochrome P450, resulting in the hindrance of the formation of hepatoxic free radicals. The site-specific oxidative damage in some susceptible amino acids of proteins is now regarded as the major cause of metabolic dysfunction during pathogenesis.[24] Attainment of near normal level of protein, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels in paracetamol-intoxicated and BHEE-treated rats confirms the hepatoprotective effect of the plant extract.

The marked elevations in bilirubin and urea levels in the serum of Group II paracetamol-intoxicated rats were significantly decreased in the BHEE-treated animals. Bilirubin is the conventional indicator of liver diseases.[25] These biochemical restorations may be due to the inhibitory effects on cytochrome P450 or/and promotion of its glucuronidation.[26]

Assessment of liver can be made by estimating the activities of SGOT, SGPT, ALP, LDH, and 5′-nucleotidase, which are enzymes originally present in higher concentration in cytoplasm. When there is hepatopathy, these enzymes leak into the blood stream in conformity with the extent of liver damage.[27] The elevated level of these entire marker enzymes observed in the Group II paracetamol-treated rats in this present study corresponded to the extensive liver damage induced by toxin. The reduced concentrations of ALT as a result of plant extract administration observed during the present study might probably be, in part, due to the prescence of catechins in the extract.[28] The tendency of these marker enzymes, to return to near normalcy would be owing to the anti-hepatotoxic effect of BHEE. These results were found comparable to silymarin.

Histopathologic studies [Figure 6] also supported the evidence of biochemical analysis. Histological examination of rat liver treated with paracetamol shows significant hepatotoxicity characterized by hypertrophy and necrosis of hepatocytes and shrinkage of the central veins. There was extensive infiltration of the lymphocytes and Kupffer cells around the central vein and loss of cellular boundaries. However, in animals treated with alcoholic extract of the biherbal mixture (200 and 400 mg/kg) the severity of hepatic damage was decreased when compared with the hepatic damage observed in individual alcoholic extracts. Supplementation of biherbal ethanolic extract reduced the hypertrophy of hepatocytes and lymphocyte infiltration in the central vein was decreased, which further indicated its significant hepatoprotective effect.

Figure 6.

(a) Group I: Effect of biherbal ethanolic extract (BHEE) on total bilirubin against paracetamol-induced hepatotoxicity in rats. (b) Group II (paracetamol-treated rat): Perivenular inflammatory infiltration and hepatocytic fatty change, diffuse mild hepatocellular vacuolation. (c) Group III (Achyranthes aspera 400 mg): Change central vein, mild fatty change. (d) Group IV (Aerva lanata 400 mg): Dilated central vein. Mild sinusoidal dilation: No hepatocellular damage. (e) Group V (BHEE 200 mg): Perilobular hepatocellular fatty change, (mild fatty change), Peripheral lobule (f) Group VI (BHEE 400 mg): Sinusoidal dilation and peripheral hepatocytic fatty change. (g) Group VI (BHEE 400 mg): Sinusoidal dilation and peripheral hepatocytic fatty change

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the BHEE offered protection from paracetamol-induced liver damage. The protection against liver damage by the BHEE was found comparable to silymarin. The possible mechanism responsible for the protection of paracetamol-induced liver damage by BHEE may be that it could act as a free radical scavenger intercepting the radicals involved in paracetamol metabolism by microsomal enzymes. By trapping oxygen-related free radicals, the extract could hinder their interaction with polyunsaturated fatty acids and would abolish the enhancement of lipid peroxidative processes. It is well documented that flavonoids and glycosides are strong antioxidants. Antioxidant principles from herbal resources are multifaceted in their effects and provide enormous scope in correcting the imbalance through regular intake of a proper diet. Thus, from the foregoing findings, it was observed that BHEE is a promising hepatoprotective agent and this hepatoprotective activity of BHEE may be due to the antioxidant chemicals present in it. Work is in progress here to identify the antioxidant ability of this biherbal extract.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil,

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zimmerman HJ, Ishak KG, MacSween R, Anthony PP, Scheuer PJ, Burt AD, et al. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994. Hepatic injury due to drugs and toxins, in Pathology of Liver; pp. 563–634. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyd EH, Bereczky GM. Liver necrosis from paracetamol. Br J Pharmacol. 1966;26:606–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1966.tb01841.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahlin D, Miwa G, Lu A, Nelson S. N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine: A cytochrome P-450- mediated oxidation product of acetaminophen. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1984;8:1327–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.5.1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moron MS, Depierre JW, Mannervik B. Levels of glutathione, glulathione reductase and glutathione-S-transferase activities in rat lung and liver. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;582:67–78. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta AK, Chitme H, Dass SK, Misra N. Hepatoprotective activity of Rauwolfia serpentina rhizome in paracetamol intoxicated rats. J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;1:82–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chattopadhyay RR. Possible mechanism of hepatoprotective activity of Azadirachta indica leaf extract: Part II. J Ethnopharmacol. 2003;89:217–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf PL. Biochemical diagnosis of liver disease. Indian J Clin Biochem. 1999;14:59–64. doi: 10.1007/BF02869152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guntupalli M, Chandana V, Palpu Pushpangadan, Annie Shirwaikar IJ. Hepatoprotective effects of rubiadin, a major constituent of Rubia cordifolia Linn. J Ethnopharmacol. 2006;103:484–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2005.08.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shahani S. Evaluation of hepatoprotective efficacy of APCL-A polyherbal formulation in-vivo in rats. Indian Drugs. 1999;36:628–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girach RD, Khan ASA. Ethno medicinal uses of Achyranthes aspera leaves in Orissa (India) Int J Pharmacogn. 1992;30:113–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiritikar KR, Basu BD. Dehradun,India: International book distributors; 1996. Indian Medicinal Plants; pp. 2064–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reitman S, Frankel S. A colorimetric method for the determination of Serum Glutamate Pyruvate Transaminase and Serum Glutamate Oxaloacetate Transaminase. Am J Clin Path. 1957;28:56–62. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/28.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kind PR, King EJ. Determination of Serum Alkaline Phosphatase. J Clin Path. 1954;7:132–6. doi: 10.1136/jcp.7.4.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gornall A, Bardawil J, David MM. Determination of Protein by Biuret modified method. Biol Chem. 1949;177:751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wybenga DR, Pileggi VJ, Dirstine PI, Giorgio D. Direct manual determination of serum total cholesterol with a single stable reagent. Clin Chem. 1980;16:980–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malloy HT, Evelyn KA. The determination of bilirubin. J Biol Chem. 1937;119:481–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fossati P, Lorenzo P. Estimation of Triglycerides. Clin Chem. 1983;28:2077–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bousquet BF, Julien R, Bon R, Dreux C. Determination of Blood urea. Ann Biol Clin. 1971;29:415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Recknagel RO, Glende EA, Dolak JA, Waller RL. Mechanisms of carbon tetrachloride toxicity. Pharmacol Ther. 1989;43:139–54. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(89)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valenzuela A, Garrido A. Biochemical bases of the pharmacological action of the flavonoid silymarin and of its structural isomer silibinin. Biol Res. 1994;27:105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valenzuela A, Guerra R, Videla LA. Antioxidant properties of the flavonoids silybin and (1)-cyanidanol-3: Comparison with butylated hydroxyanisole and butylated hydroxytoluene. Planta Med. 1986;6:438–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-969247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bosisio E, Benelli C, Pirola O. Effect of the flavanolignans of Silybum marianum L.on lipid peroxidation in rat liver microsomes and freshly isolated hepatocytes. Pharmacol Res. 1992;25:147–54. doi: 10.1016/1043-6618(92)91383-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Letteron P, Labbe G, Degott C, Berson A, Fromenty B, Delaforge M, et al. Mechanism for the protective effects of silymarin against carbon tetrachloride-induced lipid peroxidation and hepatotoxicity in mice: Evidence that silymarin acts both as an inhibitor of metabolic activation and as a chain-breaking antioxidant. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;39:2027–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90625-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bandyopadhyay U, Dipak D, Banerji Ranjit K. Reactive oxygen species: Oxidative damage and pathogenesis. Curr Sci. 1999;5:658–66. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Achliya GS, Wadodkar SG, Dorle AK. Evaluation of hepatoprotective effect of Amalkadi Ghrita against carbon tetra chloride induced hepatic damage in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;90:229–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2003.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavin C, Mace K, Offord EA, Schilter B. Protective effects of coffee diterpenes against aflatoxin B1-induced genotoxicity: Mechanisms in rat and human cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39:549–56. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00168-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nkosi CZ, Opoku AR, Terblanche SE. Effect of pumpkin seed (Cucurbita pepo) protein isolate on the activity levels of certain plasma enzymes in CCl4-induced liver injury in low-protein fed rats. Phy Ther Res. 2005;19:341–5. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naidoo V, Chikoto H, Bekker LC, Eloff JN. Antioxidant compounds in Rhoicissus tridentata extracts may explain their antibabesial activity. S Afr J Sci. 2006;102:198–200. [Google Scholar]