Abstract

Although stigma towards HIV-positive women for both continuing and terminating a pregnancy has been documented, to date few studies have examined relative stigma towards one outcome versus the other. This study seeks to describe community attitudes towards each of two possible elective outcome of an HIV-positive woman’s pregnancy – induced abortion or birth – to determine which garners more stigma and document characteristics of community members associated with stigmatising attitudes towards each outcome. Data come from community-based interviews with reproductive-aged men and women, 2401 in Zambia and 2452 in Nigeria. Bivariate and multivariate analyses revealed that respondents from both countries overwhelmingly favoured continued childbearing for HIV-positive pregnant women, but support for induced abortion was slightly higher in scenarios in which anti-retroviral therapy (ART) was unavailable. Zambian respondents held more stigmatising attitudes towards abortion for HIV-positive women than did Nigerian respondents. Women held more stigmatising attitudes towards abortion for HIV-positive women than men, particularly in Zambia. From a sexual and reproductive health and rights perspective, efforts to assist HIV-positive women in preventing unintended pregnancy and to support them in their pregnancy decisions when they do become pregnant should be encouraged in order to combat the social stigma documented in this paper.

Keywords: Africa, stigma, pregnancy, HIV/AIDS

Introduction

Social expectations around reproduction play a role in individual decision-making regarding fertility decisions. People living with HIV are no exception. As antiretroviral therapy (ART) is increasingly available for persons living with HIV, many of whom are within their reproductive years, decisions about childbearing, which once seemed off the table for many HIV-positive individuals, are now back on the table again. Some women with HIV who become unintentionally pregnant weigh continuing the pregnancy versus terminating the pregnancy, with HIV being one factor that may be influencing women’s decisions on how to manage a pregnancy (Stephenson and Griffioen 1996; Desgrées de Loû et al. 2002; Nöstlinger et al. 2006). Pregnancy outcomes among HIV-positive women are likely influenced by several factors, including individuals’ perceptions of the probability of mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Without ART, transmission from HIV-positive woman to her child during pregnancy ranges from 15–45%; this rate can be reduced to below 5% when ART is introduced during the prenatal period (WHO 2010). Moreover, the presence of Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission (PMTCT) programmes may increase HIV-positive men’s and women’s fertility desires (Cooper et al. 2007).

In spite of strong pronatalist attitudes in Africa (Airhihenbuwa 2006), social stigma against continued childbearing by HIV-positive women exists (London, Orner and Myer 2008). In South Africa most women with HIV perceived strong community disapproval associated with HIV and childbearing (Cooper et al. 2007). HIV-positive mothers’ perceptions of disapproval from community members regarding their mothering abilities is substantiated by studies from sub-Saharan Africa (Myer, Morroni and Cooper 2006; Orner et al. 2010; Orner, de Bruyn and Cooper, 2011). Previous qualitative work in Zambia identified community approbation against HIV-positive women getting pregnant (Rutenberg, Biddlecom and Kaona 2000). HIV-positive women in the United States who have children are perceived to be inadequate mothers for several reasons such as neglecting the care of existing children, potentially increasing the number of orphans that are left behind if they pass away and possibly passing along their infection to a future child (Sandelowski and Barroso 2003). The presence of these community attitudes decreases the odds of a woman choosing to become pregnant following an HIV-positive diagnosis (Craft et al. 2007).

Fewer studies have examined abortion in the context of HIV. Studies in Zimbabwe and Uganda showed that HIV-positive women’s consideration of abortions was constrained by the poor availability of safe abortion services (Feldman and Maposhere 2003). In South Africa, where abortion is legal under broad grounds, HIV-positive women were pressured by healthcare providers to have abortions (Cooper et al. 2005); the opposite pressure was found in Uganda, where abortion is highly legally restricted (Moore et al. 2006). Also in South Africa, HIV-positive women who consider or have abortions balance the simultaneous stigma associated both with being HIV-positive and with abortion, although abortion seems to be more stigmatised than HIV/AIDS (Orner et al. 2010; Orner, de Bruyn and Cooper, 2011).

Although stigma towards the two most common pregnancy outcomes for an HIV-positive woman has been documented, to date, few studies have examined relative stigma towards HIV-positive women for one outcome versus the other. We define relative stigma as the act of treating one stigmatised behaviour more or less negatively than another stigmatised behaviour. We begin from the premise that HIV-positive women who get pregnant are already in danger of social approbation due to the common disapproval of HIV-positive women reproducing (London, Orner and Myer 2008). Social expectations regarding how an HIV-positive pregnant woman should proceed likely shape a pregnant woman’s decision pathway regarding her pregnancy. Therefore, examining relative stigma of one pregnancy outcome versus another is a way of capturing social preferences regarding what an HIV-positive woman “should” do once she has become pregnant – effectively identifying community perceptions of the “lesser of two evils.” Because stigma can influence women’s pregnancy decisions, ostracise them from their communities, and impact their health-care seeking behaviours, including increasing the desire to hide an abortion in an already unsafe abortion-seeking climate (Kumar, Hessini and Mitchell 2009), it is important to understand pregnancy-related relative stigma through community attitudes towards continued childbearing and abortion among HIV-positive women, including those who are already mothers.

We sought to study these attitudes in two countries with different ethnic and socioeconomic conditions, reproductive health indicators and levels of the HIV epidemic: Zambia and Nigeria. Zambia has a relatively high HIV prevalence (14.3% in 2007), high access to ART (56% coverage), a total fertility rate of 6.2 and moderate desired family size (4.6 for women vs. 4.9 for men), and a moderately liberal abortion law that permits abortion on both health and socioeconomic grounds but poor access to safe abortion (UNAIDS 2012a; CSO 2009; Likwa, Biddlecom and Ball 2009). Nigeria has a relatively low prevalence of HIV (4.1% in 2010), limited access to ART (26% coverage), a total fertility rate of 5.7 and high desired family size (6.1 for women vs. 7.2 for men), a law that restricts abortion in almost all cases except to save a woman’s life, yet a high rate of unsafe abortion (25/1000 women aged 15–44) (UNAIDS 2012b; Henshaw et al. 1998; NPC, 2009). While no data have been collected on abortion incidence in Zambia, the World Health Organization (WHO 2012) estimates the regional abortion rate to be 38/1000, which if true, would mean a higher abortion rate than in Nigeria (Sedgh et al. 2011).

Each of the above listed indicators may influence community-based stigma about HIV-positive women continuing or terminating a pregnancy. What is deemed to be anomalous, or different from oneself, is stigmatised (Goffman 1963). For example, just as in a country with a low fertility rate, a large family may be stigmatised; in a country with a high fertility rate, a small family size may be stigmatised. Our study assumes that social location, i.e. individual-level demographic characteristics of community members, influences individuals’ social attitudes towards HIV-positive pregnant women (Genberg et al. 2009). However, whereas some characteristics such as family size are observable, HIV status and abortion experience can be hidden (Kumar, Hessini and Mitchell 2009). Therefore, even in settings where HIV and abortion are prevalent, stigma can exist towards the hypothetical “others” who experience these outcomes because the secrecy surrounding HIV and abortion renders them uncommon in the public’s mind. Stigma may even be professed and perpetrated by those who have indeed experienced the stigmatised behaviour/outcome, perhaps as a perceived mechanism of self-defence, to an even greater extent than those who have not (Kumar, Hessini and Mitchell 2009).

In settings where the HIV epidemic is more severe, HIV-related stigma may be mitigated due to more people knowing others who are living with HIV (Genberg et al. 2009). Similarly, abortion stigma may be less common in settings where abortion is more prevalent (Kumar, Hessini and Mitchell 2009). In addition, in settings where interventions to address high rates of HIV are well established, as in Zambia, reduction of HIV stigma initiatives that focus on assisting institutions with recognising stigma, confronting fears of contagion and negative social judgments, and engaging people living with HIV in programmes are often incorporated into these broad intervention programmes (Pulerwitz et al. 2010). We hypothesised that individuals in Zambia, a country with higher HIV prevalence and greater access to treatment as well as more liberal abortion laws, would report lower stigma regarding HIV-positive women either carrying pregnancies to term or terminating them as compared to individuals in Nigeria. In addition, we hypothesised that individual-level demographic characteristics of community members within each country would influence their stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing or abortion among HIV-positive pregnant women.

Our primary objectives in this analysis were to, within two different country settings, (1) describe community attitudes towards continued childbearing and abortion among HIV-positive women, (2) determine whether community members expressed more stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing compared to abortion for HIV-positive women, and (3) determine whether certain characteristics of community members were associated with expressing more stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing or abortion among HIV-positive women.

Methods

Sample selection and data collection

Data for this study come from a 2009/2010 multi-stage, cluster sample of households in three provinces in Zambia (Lusaka, Northern and Southern) and four states in Nigeria (Kaduna, Benue, Lagos, and Enugu). The provinces/states were selected to gather data from different ethnic groups and from regions with varying HIV-prevalence and fertility levels. This intra-country variation was captured not to be able to compare varying levels of stigma regionally within either country, but rather to capture national variation for an overall inter-country comparison. In order to achieve 80% statistical power, based on an overall proportion of 30% (the approximate proportion of women who want no more children) and a detectable difference on these outcomes of 5% between those who perceive themselves at high risk of HIV and those who perceive themselves at lower risk, we sought a sample size of 1300 men aged 18–59 years and 1300 women aged 18–49 years for both Zambia and Nigeria. The study was approved by the Guttmacher Institute’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), the University of Ibadan/University College Hospital IRB, and the University of Zambia Biomedical Research Ethics Committee.

The study sample in Zambia was a sub-sample of the sample for the 2007 Zambia Demographic and Health Survey. In order to yield the target sample size, 60 Enumeration Areas (EAs) were selected by equal probability systematic sampling, including 38 rural and 22 urban EAs. The total sample was allocated to the provinces proportional to its projected population of 2009 distributed by urban and rural areas, which was obtained from the Central Statistical Office.

In Nigeria, one rural and one urban Local Government Area (LGA) were randomly selected from each state. Ten and 20 EAs were then systematically selected from the rural and urban LGAs respectively. In the selected EAs, 10% of households were selected systematically.

The questionnaire included the core set of topics covered in Demographic and Health Surveys in addition to HIV-related questions including the respondent's HIV status and perception of risk for contracting HIV, and attitudes about continued childbearing and abortion in the context of HIV, as well as a vignette that presented three scenarios regarding a pregnant woman determining what to do about her pregnancy (if she has general health problems, if she is HIV-positive but not on ART, and if she is HIV-positive and on ART). It was not explicitly stated that this was an intended or unintended pregnancy. Respondents were asked to give their opinions about how the woman should proceed (continue or terminate) in each of the scenarios. The questionnaires were developed in English and translated into three local languages in Zambia (Tonga, Nyanja and Bemba) and four local languages in Nigeria (Yoruba, Igbo, Hausa and Tiv). Translated questionnaires were pilot tested in each country. All interviewers (15 in Zambia and 24 in Nigeria) participated in country-specific five-day trainings on interview techniques, questionnaire wording, confidentiality, mapping and household listing, and other field logistics prior to beginning fieldwork. All eligible adults in selected households included in the study (women 18–49 and men 18–59) were interviewed by trained interviewers of the same region as the respondents; interviews took approximately one hour. Data collection lasted from October 2009 – February 2010 in Zambia and from November 2009 – May 2010 in Nigeria.

Data processing and analysis

Data were double entered into Census and Surveys Processing System (version 4.0), exported to SPSS (version 15.0) for cleaning, and transferred to Stata (version 11.2) for analysis. Data were weighted to reflect the total population of reproductive aged men (18–59) and women (18–49) in the three study provinces in Zambia in 2007 and in the four study regions in Nigeria in 2008, the most recent years for which information on the strata was available.

We relied on respondents’ perceived risk of having contracted HIV as a measure instead of HIV status itself, as the number of men and women in the community who indicated that they were HIV positive in response to the HIV status question was too small to analyze. Responses to each of the three vignette scenarios were “continue the pregnancy,” “end the pregnancy,” and “don’t know.” For the two HIV-positive scenarios, we created dichotomous variables to represent support for continuing the pregnancy and support for terminating the pregnancy (0 = no and don’t know, 1 = yes). We entered 10 attitudinal questions into two separately generated factor analyses (one for each country dataset) to identify items in the questionnaire that held together closely to represent the concepts of stigmatisation towards continued childbearing and stigmatisation towards abortion for HIV-positive women. The two factor analyses generated similar results, which yielded two indices to represent the two stigmatisation concepts, each made up of three questions. Individual items included in the indices, the wording of which is presented in the figures in the next section, were coded on a scale of 1 (agree) to 3 (disagree); therefore each index ranges from 3, representing low stigma, to 9, representing high stigma. Among respondents who expressed discordance in stigmatising attitudes towards the two pregnancy outcomes (low stigma scores of 5 or below on one and high stigma scores of 6 and above on the other), we created a dichotomous measure of relative stigma to represent highly stigmatising attitudes towards abortion for HIV-positive women as compared to highly stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing for HIV-positive women. Respondents who expressed high stigma towards abortion (scores 6 and above) and low stigma towards continued childbearing (scores 5 and below) were compared to the reference category of respondents who expressed high stigma towards continued childbearing and low stigma towards abortion.

We present descriptive statistics of respondents’ demographic characteristics and attitudes toward continued childbearing and abortion for HIV-positive women as measured by support for abortion in the vignette scenarios and disagreement with statements about continued childbearing and abortion among HIV-positive pregnant women. Mean scores and descriptive statistics of each stigmatisation index are also presented. We conducted chi-square analyses to examine differences in attitudes towards both pregnancy outcomes between men and women in each country. Finally, we developed multivariate logistic regression models to examine the associations between respondent characteristics and stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing and abortion in the context of HIV. All analyses accounted for weighting necessary for the clustered sample design in this study.

Results

Our final sample included 2,401 respondents from Zambia (92.4% response rate) and 2,452 respondents from Nigeria (94.3% response rate). Select demographic and HIV-related characteristics of respondents are presented in Table 1. Notably, about half of the Zambian sample perceived themselves to be at least at low risk of having contracted HIV; in Nigeria, this proportion was 30%.

Table 1.

Demographic and reproductive health characteristics of study sample, Zambia and Nigeria, 2009–2010

| Demographic characteristics | Zambia (N = 2401) % |

Nigeria (N = 2452) % |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 47 | 50 | |

| Female | 53 | 50 | |

| Age | |||

| 15–19 | 11 | 20 | |

| 20–29 | 38 | 41 | |

| 30–39 | 31 | 21 | |

| 40 and older | 21 | 18 | |

| Number of children | |||

| 0 | 24 | 53 | |

| 1–2 | 23 | 16 | |

| 3–4 | 22 | 13 | |

| 5+ | 31 | 19 | |

| Education | |||

| None | 8 | 20 | |

| Some primary | 23 | 21 | |

| Completed primary | 53 | 43 | |

| Above primary | 16 | 16 | |

| Residence | |||

| Rural | 56 | 59 | |

| Urban | 44 | 41 | |

| Relationship status | |||

| Not in union | 34 | 53 | |

| In union | 66 | 47 | |

| Religion | |||

| Catholic | 24 | 36 | |

| Protestant | 49 | 23 | |

| Pentecostal/Charismatic | 15 | 11 | |

| Other Christian | 9 | 3 | |

| Other | 9 | 27 | |

| Perceived risk of getting AIDS virus | |||

| None | 51 | 70 | |

| Low | 38 | 17 | |

| Moderate to great | 11 | 12 | |

Choosing between possible pregnancy outcomes in a vignette scenario

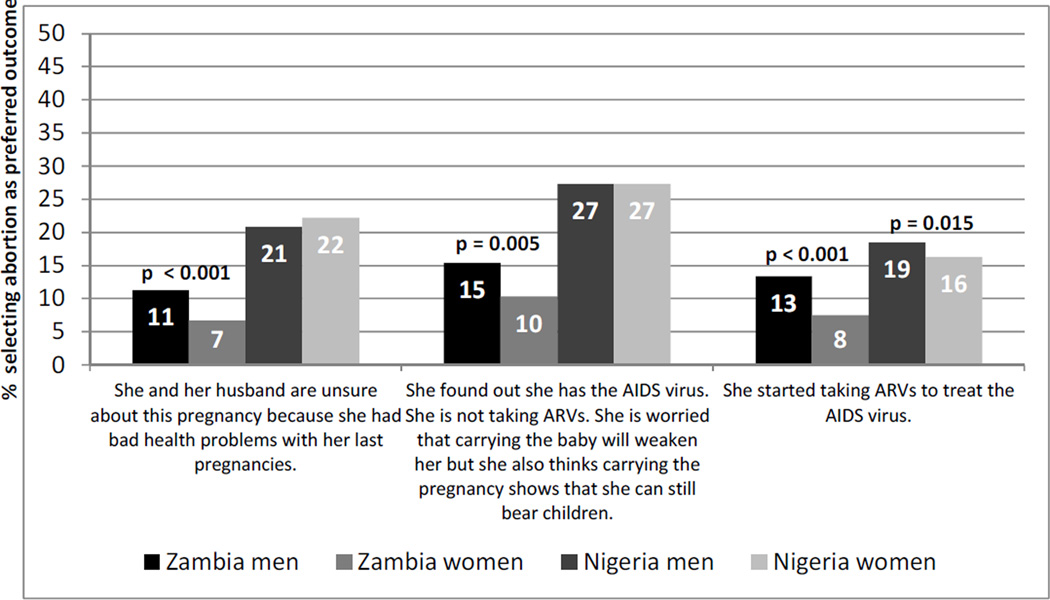

When presented with a hypothetical scenario in which a pregnant wife must decide how to proceed under different scenarios, respondents from both countries overwhelmingly favoured continuing the pregnancy in each of the three situations (Figure 1). However, support for terminating the pregnancy followed a similar pattern in both countries: increasing when the woman was not on treatment and decreasing when she was on ART.

Figure 1.

Percentage of respondents choosing abortion as preferred pregnancy outcome for a woman, in vignette scenarios about a hypothetical couple deciding how to proceed with a pregnancy in differing circumstances

Responding to the vignettes, both Nigerian men and women reported higher levels of support for ending the pregnancy than did men and women in Zambia. Over one-quarter of respondents in Nigeria indicated that the woman who was not using ART should end her pregnancy. This was the highest level of support for abortion captured. Compared to women, Zambian men were more likely to support abortion in all circumstances and Nigerian men were more likely to support abortion for an HIV-positive woman taking ART.

In Zambia, controlling for age, parity, education and perceived risk of HIV, women responding to the vignettes were more likely than men to be in favour of pregnancy continuation regardless of whether or not the woman was on ART (data not shown in table). More highly educated individuals were less likely to be in favour of the woman continuing the pregnancy in the absence of treatment. In the absence of ART, individuals who perceived themselves to be at moderate to great risk of contracting HIV were significantly less likely to choose pregnancy continuation. In Nigeria, at the multivariate level, regardless of the presence of ART, older age was negatively correlated with support for continuing the pregnancy. Compared to those without children, parents were more likely to choose continuing the pregnancy in either treatment scenario. Nigerian individuals with no education were more likely to favour continuing the pregnancy in the presence of ART than those who had completed primary education. In both treatment scenarios, men and women in Nigeria who perceived themselves to be at low risk of contracting HIV were significantly less likely than those who perceived themselves to be at no risk to favour the woman continuing the pregnancy.

Stigmatising attitudes towards HIV-positive women for continuing versus terminating a pregnancy

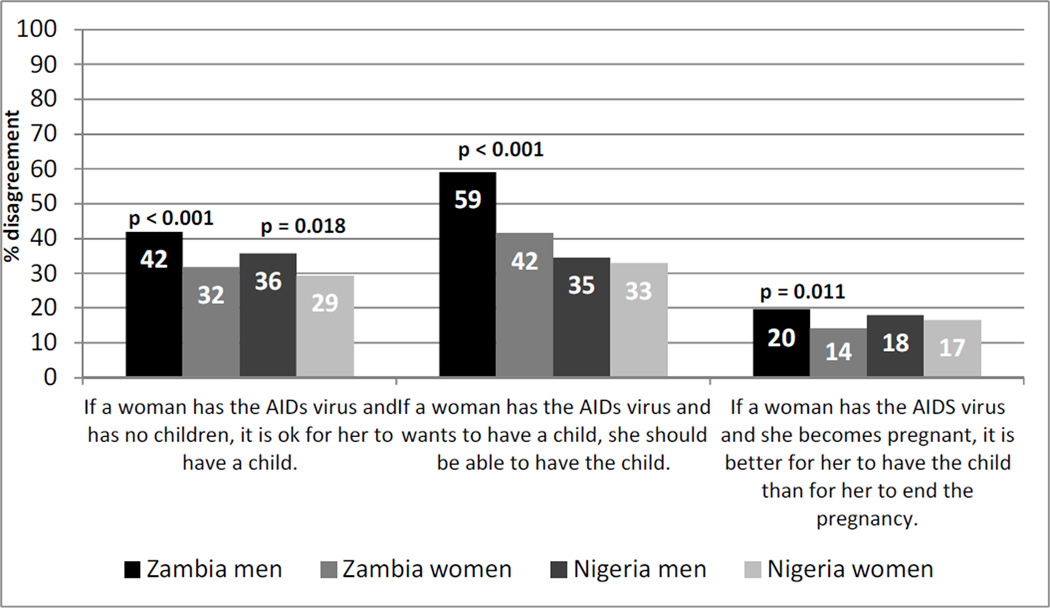

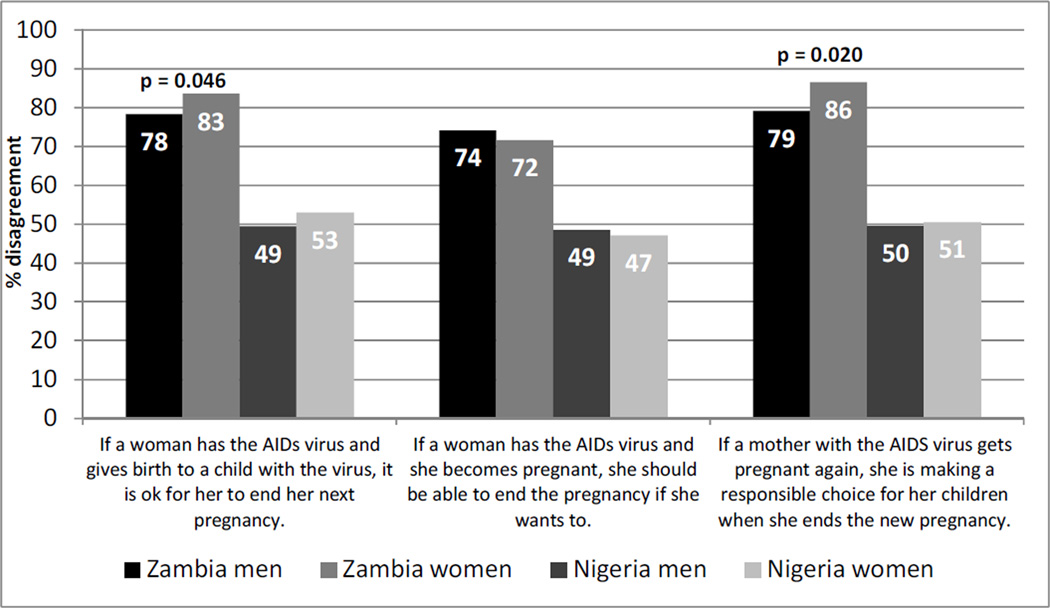

Many patterns identified above in the vignettes were echoed in men’s and women’s responses to individual items assessing attitudes towards continued childbearing and abortion in the context of HIV (Figures 2 and 3). In both Zambia and Nigeria, men and women held more stigmatising attitudes towards abortion than towards continued childbearing for an HIV-positive pregnant woman. In Zambia, men were more likely to stigmatize pregnancy continuation while women were more likely to stigmatise abortion among HIV-positive women. Nigerian men and women had lower levels of stigma towards both potential outcomes of a pregnancy of an HIV-positive woman and they were more similar in their attitudes towards HIV-positive women for each pregnancy outcome.

Figure 2.

Percentage of respondents reporting disagreement with individual attitudinal items regarding continued childbearing among HIV-positive women

Figure 3.

Percentage of respondents reporting disagreement with individual attitudinal items regarding abortion among HIV-positive women

The individual attitudinal items presented above in Figure 2 were merged to create an index of stigmatisation towards continued childbearing in the context of HIV, while the items in Figure 3 were merged to create an index of stigmatisation towards abortion in the context of HIV. Descriptive statistics of the two indices are presented in Table 2. Mean index scores for stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing for HIV-positive women were lower than those towards abortion in both countries. Mean scores for stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing for HIV-positive women were similar between the two countries, but scores indicated greater stigma towards terminating a pregnancy in Zambia than in Nigeria. Zambian men were more likely than Zambian women to hold stigmatising attitudes towards continued childbearing for HIV-positive women; no significant differences in stigmatising attitudes existed between men and women regarding abortion for HIV-positive women in Zambia and regarding either outcome of a pregnancy in Nigeria.

Table 2.

Mean scores of the two stigmatising indices, continued childbearing among HIV-positive women and abortion among HIV-positive women, based on a scale of 3–9, with standard deviations (SDs), and percentage of respondents characterised as falling into each of three categories within each index (low, moderate or highly stigmatising attitudes towards each pregnancy outcome), women and men, Zambia and Nigeria, 2009–2010

| Zambia | Nigeria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stigmatising index | Women | Men | Women | Men |

| Continued childbearing among HIV-Positive Women | 4.60 (1.78) | 5.35 (1.82) | 4.39 (1.83) | 4.62 (1.99) |

| Low stigma (3–4) | 47.57*** | 25.81 | 52.54 | 50.32 |

| Moderate stigma (5–6) | 27.87 | 35.58 | 22.32 | 20.72 |

| High stigma (7–9) | 24.56 | 38.62 | 25.15 | 28.95 |

| Abortion among HIV-Positive Women | 7.83 (1.82) | 7.73 (1.91) | 6.02 (2.46) | 6.01 (2.52) |

| Low stigma (3–4) | 6.083 | 8.324 | 33.37 | 34.77 |

| Moderate stigma (5–6) | 10.05 | 11.28 | 15.75 | 16.36 |

| High stigma (7–9) | 83.87 | 80.4 | 50.88 | 48.87 |

Women and men in Zambia are significantly different at p <0.001 in their scores on the index of stigmatisation of continued childbearing among HIV-positive women

Relative stigma towards an HIV-positive woman terminating her pregnancy, assessed by comparing individuals who expressed highly stigmatising attitudes towards abortion for HIV-positive women and lower stigmatising attitudes towards continuing pregnancy to individuals with the opposite stigmatising attitudes is presented in Table 3. After controlling for respondent’s parity, education level and perceived risk of HIV, in Zambia, female gender and older age were both associated with higher odds of expressing relative stigma towards abortion for HIV-positive women, while having five or more children and education were associated with lower odds of this relative stigma. In Nigeria, female gender and no education were both associated with increased odds of expressing relative stigma towards abortion for HIV-positive women. Perceived risk of contracting HIV was not associated with relative stigma towards abortion for HIV-positive women in either country.

Table 3.

Odds ratios for logistic regression models examining respondent characteristics associated with relative stigma towards abortion for HIV-positive women as compared to stigma towards continued childbearing for HIV-positive women, Zambia and Nigeria, 2009–2010

| Relative stigma towards HIV-positive women having abortions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | Zambia N = 868 |

Nigeria N = 408 |

|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | 1 | |

| Female | 4.02** | 1.63* | |

| Age | |||

| 15–19 | 1 | 1 | |

| 20–29 | 1.91 | 1.56 | |

| 30–39 | 6.96* | 2.16 | |

| 40 and older | 6.40** | 1.29 | |

| Number of children | |||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 1–2 | 2.45 | 1.35 | |

| 3–4 | 0.44 | 0.83 | |

| 5+ | 0.29* | 1.35 | |

| Education | |||

| None | 1.40 | 4.67** | |

| Some primary | 0.36* | 1.42 | |

| Completed primary | 1 | 1 | |

| Above primary | 0.26** | 1.63 | |

| Perceived risk of getting AIDS virus | |||

| None | 1 | 1 | |

| Low | 0.82 | 0.89 | |

| Moderate to great | 0.74 | 1.51 | |

p <0.05,

p <0.01,

p<0.001

Note: Populations restricted to respondents that indicated differences in stigmatising attitudes towards HIV-positive women continuing versus terminating their pregnancies (not high/high or low/low stigma towards both outcomes)

Discussion

Findings from our study indicate that community members in Zambia and Nigeria favoured HIV-positive women continuing their pregnancies, with or without access to ART. Contrary to our hypothesis, despite the more liberal abortion law, Zambian respondents expressed less support than Nigerian respondents for HIV-positive women having abortions. The stigma associated with HIV-positive women having abortions might not be different from general stigma towards women having abortions. It is possible, though, that these respondents may be underreporting their support for abortion due to broad-based stigma against abortion (Kumar, Hessini and Mitchell 2009; Harries, Stinson and Orner 2009). PMTCT programmes reach over 50% of the population in Zambia, but less than a quarter of the population in Nigeria (Country Report, Zambia; Country Report, Nigeria). With increasing availability of ART, both in general and within the context of PMTCT, there has been an increasing desire for procreation by persons living with HIV (Oladapo et al. 2005; Cooper et al 2007; HIV/AIDS Division FMoHoN 2011). In addition, given the programmatic focus on having healthy children, PMTCT programmes likely do not include discussions regarding the option of pregnancy termination for HIV-positive women. This dynamic may also be partially accounting for the reduced support for abortion in Zambia as compared to Nigeria.

In Zambia where HIV is more widespread, individuals’ own perceived risk of contracting HIV was positively associated with greater support for an HIV-positive woman having an abortion when she did not have access to ART. This finding may reflect individuals’ perceptions of how they would manage a pregnancy in a similar situation, as personal vulnerability may be correlated with compassion towards a woman finding herself pregnant when she knows she’s already HIV-positive. Since we use perceived risk as a proxy for HIV status in this analysis, this association may also be capturing an “insider’s perspective” as to what he or she would do as an HIV-positive individual in a similar situation.

Women hold more stigmatising attitudes towards HIV-positive women having abortions than do men, particularly in Zambia. This is likely due to a strong societal emphasis placed on women’s role as mothers in these pronatalist societal contexts (Airhihenbuwa 2006). Women transgress this motherhood role when they decide to have an abortion (Kumar, Hessini and Mitchell 2009; Norris et al. 2011). HIV-positive women living in both Zambia and Nigeria may face difficulty in achieving their fertility desires, given the community-based stigma associated with both pregnancy outcomes. HIV-positive women who become pregnant are essentially caught between a rock and a hard place; they are stigmatised regardless of their pregnancy outcome likely due to the root of the stigma being based in disapproval of HIV-positive women becoming pregnant in the first place. If pregnancy itself is the main driver of community-based stigma towards HIV-positive women, having an abortion allows one to hide that stigmatised behaviour while continued childbearing makes that stigmatised behaviour more visible.

We found varying degrees of support for our hypothesis that community members’ characteristics shape their attitudes towards continued childbearing and abortion among HIV-positive women. The association between age and support for abortion in Nigeria may be linked to the prevalence of unsafe abortion in Nigeria; older individuals have a higher likelihood of knowing someone who has had an abortion. The association between parity and support for abortion for HIV-positive women in Zambia may be connected to the higher prevalence of HIV in that country; individuals with more children may have greater empathy for an HIV-positive woman weighing how to resolve her pregnancy. In both countries, education may be a proxy measure of knowledge about abortion legality, availability and access, thus normalising and reducing the stigma associated with this outcome.

A better understanding of the relative stigma we have documented in our study will enable HIV and reproductive healthcare providers to improve services for HIV-positive pregnant women, especially those who have terminated or who will terminate their pregnancies. Aspects of respondents’ demographic profiles which make them more receptive to the reproductive rights of HIV-positive individuals can be used to foster greater social support for reproductive decision-making. Education can address stigma through providing a deeper understanding of issues facing HIV-positive women and may thereby promote greater acceptance of reproductive decisions of people living with HIV. Perceived risk for contracting HIV could similarly be a tool to sensitise community members to the difficult decisions HIV-positive individuals are facing. Providers, who also report greater support for childbearing versus abortion among HIV-positive women (Awulode 2012), should recognise the social disapproval that HIV-positive pregnant women face, regardless of the pregnancy outcome that they choose, when counselling them about their pregnancy. For instance, HIV Information, Education and Communication packages should be updated to acknowledge the community-based stigma that HIV-positive women may face during pregnancy and to combat the greater stigma towards abortion for HIV-positive pregnant women among all individuals, especially among women and older individuals in Zambia and among women and less educated individuals in Nigeria.

Policy recommendations have the potential to mitigate HIV transmission and unintended pregnancy. Unmet need for contraception is relatively high in both countries (Westoff 2006). Efforts to improve voluntary contraceptive use among individuals in both countries who perceive themselves to be at risk of contracting HIV should be endorsed. Policies that focus on improving access to, and use of, contraceptive methods would allow women who are HIV-positive and do not want to become pregnant to avoid the stigma associated with pregnancy and its outcomes that we have documented among community members. Finally, with increased attention being paid to the importance of integration between HIV-related and family planning services, including non-judgmental and non-directive information on pregnancy options, including abortion in settings where it is legal, in PMTCT and other HIV-related programmes would help to combat the widespread stigmatisation of abortion documented in this study.

The strengths of this study include relying on data from a community-based sample rather than a facility-based one as well as including male perspectives on abortion; however, limitations still exist. We relied on self-reported perceived risk of HIV for this analysis, which may be underreported and/or may not accurately reflect actual status. Due to the sensitive nature of questions regarding abortion, respondents may have provided answers that were more socially acceptable rather than ones that accurately reflected their own perspectives on abortion. In the questionnaire we did not clarify whether the pregnancies of HIV-positive women described were intended or unintended; this omission likely influenced respondents’ attitudes towards the preferred pregnancy outcome of an HIV-positive woman. This may especially be the case in Nigeria, where rates of unplanned pregnancy are 14%, as compared to 41% in Zambia (CSO 2009; Hussain et al. 2005). In addition, our data are unable to tease out differences in individuals’ attitudes toward HIV-positive women who intentionally become pregnant in the face of stigma as compared to HIV-positive women who experienced an unintended pregnancy. However, the rights of all women to have or not to have a child, regardless of HIV status, should be emphasised (London, Orner and Myer 2008). Furthermore, our analysis cannot measure whether stigma expressed through these attitudinal measures translated into stigmatising actions by respondents or whether HIV-positive women were in fact aware of stigma as expressed by the respondents (Norris et al. 2011). Finally, these quantitative data cannot illuminate why differences exist in stigma between Nigeria and Zambia.

From a sexual and reproductive health and rights perspective, HIV-positive women should be able to decide the best pregnancy outcome for their personal circumstances, free of stigma and judgment from others regarding their decision. WHO, the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), and the Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) all affirm the reproductive rights of HIV-positive individuals to choose between continuing and terminating a pregnancy, calling for access to safe abortion services in countries where it is legal for individuals who choose the latter option (WHO 2012, UNAIDS 2006, OHCRC 2010). HIV-positive women who become pregnant internalise these stigmatising attitudes from the community, resulting in reduced disclosure regarding the pregnancy and continued silence about the need for, or experience of, abortion (Orner et al. 2010; Orner, de Bruyn and Cooper, 2011). More research, particularly qualitative explorations, into how HIV-positive women perceive community stigma about HIV-positive pregnancy as well as broader consequences of abortion stigma for HIV-positive women is thus warranted. We need to help HIV-positive women prevent unintended pregnancies as well as support them when they do become pregnant with an intended pregnancy, addressing the social attitudes and perceptions that underlie stigma. Efforts to increase access to ART should be encouraged for HIV-positive women who decide to continue their pregnancies, while access to contraceptive services and safe abortion care should be emphasised to assist HIV-positive women who do not want to become, or be, pregnant.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Akin Bankole and Ann Biddlecom for their contributions to project conceptualisation and survey design; Suzette Audam, Liz Carlin, Allison Grossman and Jesse Philbin for research support; and Heather Boonstra for reviewing the manuscript. The research on which this paper was based was funded by the National Institutes of Health under grant 1R01HD058359-01. The conclusions presented are those of the authors.

References

- Airhihenbuwa CO. Healing our differences: The crisis of global health and the politics of identity. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Awulode O, Bankole A, Moore A, Adewole I, Oladokun A, Sedgh G, Bweupe M. Comparing health care providers and HIV positive women's perspectives on pregnancy and abortion-related services to HIV-positive adults in the era of care and treatment for HIV in Zambia and Nigeria; Paper presented at the International AIDS Conference; 22–27 July; Washington, DC. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Central Statistical Office, Ministry of Health, Tropical Diseases Research Centre, University of Zambia, and Macro International Inc. Zambia demographic and health survey 2007. Calverton, MD: CSO and Macro International, Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Bracken H, Myer L, Zweigenthal V, Harries J, Orner P, Manjezi N, Ngubane P. Reproductive intentions and choices among HIV-infected individuals in Cape Town, South Africa: Lessons for reproductive policy and service provision from a qualitative study. New York City: Population Council; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D, Harries J, Myer L, Orner P, Bracken H. "Life is still going on": Reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(no. 2):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craft SM, Delaney RO, Bautista DT, Serovich J. Pregnancy decisions among women with HIV. AIDS Behavior. 2007;11(no. 6):927–935. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9219-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desgrées de Loû A, Msellati P, Viho I, Yao A, Yapi D, Kassi P, Welffens-Ekra C, Mandelbrot L, Dabis F. Contraceptive use, protected sexual intercourse and incidence of pregnancies among African HIV-infected women. International Journal of STD & AIDS. 2002;13(no. 7):462. doi: 10.1258/09564620260079617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Maposhere C. Safer sex and reproductive choice: Findings from "Positive Women: Voices and Choices" in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters. 2003;11(no. 22):162–173. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genberg BL, Hlavka Z, Konda KA, Maman S, Chariyalertsak S, Chingono A, Mbwambo J, Modiba P, Van Rooyen H, Celentano DD. A comparison of HIV/AIDS-related stigma in four countries: Negative attitudes and perceived acts of discrimination towards people living with HIV/AIDS. Social Science & Medicine. 2009;68:2279–2287. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York: Touchstone Books; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Harries J, Stinson K, Orner P. Health care providers' attitudes toward termination of pregnancy: A qualitative study in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(no. 296) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw SK, Singh S, Oye-Adeniran BA, Adewole IF, Iwere N, Cuca YP. The incidence of induced abortion in Nigeria. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;24(no. 4):156–164. [Google Scholar]

- HIV/AIDS Division Federal Ministry of Health. National guidelines for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) 4 th ed. Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S, Wulf D. Brief 2005 Series. no. 4. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2005. Reducing unintended pregnancy in Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Hessini LH, Mitchell EMH. Conceptualising abortion stigma. Culture, Health, & Sexuality. 2009;11:625–639. doi: 10.1080/13691050902842741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Likwa R, Biddlecom A, Ball H. Brief 2009 Series. No. 3. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2009. Unsafe abortion in Zambia. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- London L, Orner PJ, Myer L. “Even if you're positive, you still have rights because you are a person”: Human rights and the reproductive choice of HIV-positive persons. Developing World Bioethics. 2008;8(no. 1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A, Mirembe F, Singh S, Nakabiito C, Bankole A, Dauphine L. Child-bearing decisions among HIV-positive women: results from a qualitative study in Kampala, Uganda; Paper presented at the International AIDS Conference; August 13–18; Toronto, Canada. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Myer L, Morroni C, Cooper D. Community attitudes towards sexual activity and childbearing by HIV-positive people in South Africa. AIDS Care. 2006;18(no. 7):772–776. doi: 10.1080/09540120500409283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Population Commission (NPC) and ICF Macro. Nigeria demographic and health survey 2008. Abuja, Nigeria: National Population Commission and ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Norris A, Bessett D, Steinberg JR, Kavanaugh ML, De Zordo S, Becker D. Abortion stigma: A reconceptualization of constituents, causes, and consequences. Women's Health Issues. 2011;21(no. 3):S49–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nöstlinger C, Bartoli G, Gordillo V, Roberfroid D, Colebunders R. Children and adolescents living with HIV positive parents: Emotional and behavioural problems. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2006;1(no. 1):29–43. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCRH) Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on preventable maternal mortality and morbidity and human rights, A/HRC/14/39. Geneva: United Nations General Assembly; 2010. [accessed August 2, 2012]. < http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrcouncil/docs/14session/A.HRC.14.39.pdf>. [Google Scholar]

- Oladapo OT, Daniel OJ, Odusoga OL, Ayoola-Sotubo O. Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive patients at a suburban specialist center. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(no. 12):1672–1681. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner P, de Bruyn M, Harries J, Cooper D. A qualitative exploration of HIV-positive pregnant women’s decision-making regarding abortion in Cape Town, South Africa. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS: An Open Access Journal. 2010;7(no. 2):44–51. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2010.9724956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orner P, de Bruyn M, Cooper D. “It hurts, but I don't have a choice, I'm not working and I'm sick”: Decisions and experiences regarding abortion of women living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2011;13(no. 7):781–795. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2011.577907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E, Brown L, Mahendra V. Reducing HIV-related stigma: Lessons learned from Horizons research and programs. Public Health Reports. 2010;125(no. 2):272–281. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutenberg N, Biddlecom A, Kaona FAD. Reproductive decision-making in the context of HIV and AIDS: A qualitative study in Ndola, Zambia. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;26(no. 3):124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Motherhood in the context of maternal HIV infection. Research in Nursing & Health. 2003;26(no. 6):470–482. doi: 10.1002/nur.10109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedgh G, Singh S, Shah I, Henshaw SK, Bankole A. Induced abortion: incidence and trends worldwide from 1995 to 2008. Lancet. 2011;379(no. 9816):625–632. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61786-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson JM, Griffioen A. The effect of HIV diagnosis on reproductive experience. Study Group for the Medical Research Council Collaborative Study of Women with HIV. AIDS. 1996;10(no. 14):1683–1687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. International guidelines on HIV/AIDS and human rights: 2006 consolidated version. Geneva, Switzerland: Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCRC) and UNAIDS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Zambia country report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012a. [accessed January 17, 2012]. < http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/zambia>. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Nigeria country report. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2012b. [accessed January 17, 2012]. < http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/nigeria>. [Google Scholar]

- Westoff CF. New estimates of unmet need and the demand for family planning. DHS Comparative Report No. 14. Calverton, MD: Macro International; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: Recommendations for a public health approach - 2010 version. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2 nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]