Abstract

Objectives

To conduct on-site assessments of public health implications at key European pet markets.

Design

Observational study of visitor behaviour at stalls that displayed and sold animals, mainly amphibians and reptiles, to assess potential contamination risk from zoonotic pathogens. We noted initial modes of contact as ‘direct’ (handling animals) as well as ‘indirect’ (touching presumed contaminated animal-related sources) and observed whether these visitors subsequently touched their own head or mouth (H1), body (H2) or another person (H3).

Setting

Publicly accessible exotic animal markets in the UK, Germany and Spain.

Participants

Anonymous members of the public in a public place.

Main outcome measures

Occurrence and frequency of public contact (direct, indirect or no contact) with a presumed contaminated source.

Results

A total of 813 public visitors were observed as they attended vendors. Of these, 29 (3.6%) made direct contact with an animal and 222 (27.3%) made indirect contact with a presumed contaminated source, with subsequent modes of contact being H1 18.7%, H2 52.2% and H3 9.9%.

Conclusions

Our observations indicate that opportunities for direct and indirect contact at pet markets with presumed contaminated animals and inanimate items constitute a significant and major concern, and that public attendees are exposed to rapid contamination on their person, whether or not these contaminations become associated with any episode of disease involving themselves or others. These public health risks appear unresolvable given the format of the market environment.

Introduction

Wildlife markets occur in several regions of the world and take different forms. According to region, these markets offer animals for various reasons including culinary, medicinal and pet purposes. In this article we focus on visitor behaviour and public health implications associated with the display and sale of amphibians and reptiles at exotic pet markets in the UK and elsewhere in the European Union (EU).

Human health is reportedly a key concern at pet markets due to the attendance of the public, and because many animals are likely to harbour transmissible zoonotic pathogens.1,2 Zoonotic diseases are pathogenic infections and infestations transmissible from animals to humans. There are around 200 zoonoses3 and approximately 40 of these are associated with amphibians and reptiles (for examples, see Appendices A and B). Captive reptiles are routinely identified as reservoirs of infectious bacteria, for example, Salmonella,4 and all reptiles should be presumed to harbour Salmonella.1,5–8

In 2009, a case-control study in the UK indicated that reptile keepers were nearly 17 times more likely to get sick than those who had no contact with these animals.9 A limited study of seven door handles at a major pet market in Germany in 2010 revealed the presence of two distinct species of Salmonella, S. ramatgan and S. subspecies V (N Kutscher, personal communication, 2011), both of which are reptile-associated.

More generally, a survey of 1410 human diseases found 61% to be of potentially zoonotic origin.10 Also, 75% of global emerging human diseases are zoonotic.11

It is believed that epidemics such as SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), monkey-pox and avian influenza H5N1 may have emerged from wildlife markets.1,5,8,11 The arbitrary mixing of a wide variety of species that would not normally meet together in conditions of highly questionable animal husbandry and public health protection measures, raises multifactorial concerns about these markets and their implications for public health.1,5,8,12,13 Many cases of zoonotic disease are, however, probably misdiagnosed as other conditions and under-reporting in general is a likely major factor in under-ascertainment of cases.2 Certain common zoonoses symptomatically superficially resemble common illnesses such as gastrointestinal, respiratory, influenzal and dermatological disorders and disease. General medical practitioners who are unfamiliar with zoonoses do not typically enquire of patients about direct or indirect contact with an exotic animal.2

Significant zoonotic episodes arise from indirect contact with an animal. Indirect pathogen contamination and dissemination involving reptiles and intermediary surfaces, for example, door handles, clothes, table tops, walls, household utensils and shaking of hands, has been reported as an important factor in transmission.7,14,15 One notable example involved over 300 public attendees to a zoo who acquired Salmonella infection via a wooden stand-off barrier around a lizard enclosure and despite having had no actual contact with the reptiles.16

The presumed primary transmission route for many amphibian- and reptile-borne potential pathogens is via faecal–oral ingestion.17 However, human skin scratches from the claws of lizards,18 and bites from snakes and lizards also may transmit contaminants.14,18 Also, direct contact between any contaminated reptile and open human lesions, such as sores, or via reptile debris penetrating human orbital or aural sites, are further potential routes of infection.14 Aquatic turtles and other species of water-dwelling reptiles may contaminate large bodies of water – resulting in contaminated splashes, droplets and smears that may lead to human infection. Lizards are handled more than turtles and are more likely to introduce infection via skin scratches. Snakes are handled far more frequently than even lizards and thus may spread contaminants more widely and consistently. Diverse surfaces may act as intermediary carriers of many biotic contaminants and once a surface is contaminated, potential contagions may long persist.19

Hand washing and the use of disinfectant gels and sprays are commonly recommended and perceived as sufficient hygiene measures to eradicate Salmonella and any other potential pathogens.14,15 However, these hygiene methods, as generally practiced, do not provide reliable protection against diverse amphibian- and reptile-borne contaminants.14,15 Indeed, the use of these materials and methods may generate undue over-reliance and misplaced confidence in personal disease prevention and control that may lead to infection as a result of complacency.20

The aim of this investigation was to assess public behaviour in the context of potential contamination threats at close-quarters in a probable zoonotic pathogen rich environment. We conducted on-site assessments at three key European pet market events: Terraristika (Hamm, Germany), the IHS Show (Doncaster, UK) and Expoterraria (Sabadell, Spain) during 2011. Each event involves a substantial number of stalls that collectively sell thousands of exotic animals directly to the public. Several hundred such events occur annually throughout Europe.21

Methods

Hygiene and potential pathogen transfer were assessed by observation of public visitor and trader behaviour, with special reference to contact involving animals, animal containers, related intermediary surfaces (such as table tops), as well as contacts involving hands, body and clothing. All items (including animals and inanimate items) directly associated with the sellers’ stalls were presumed contaminated. Pathogen transfer from local contamination sources is well known, and it is reasonable to anticipate that at a stall at which animals are sold, all animals and animal-related material will probably have been exposed to microbial transfer and dissemination.

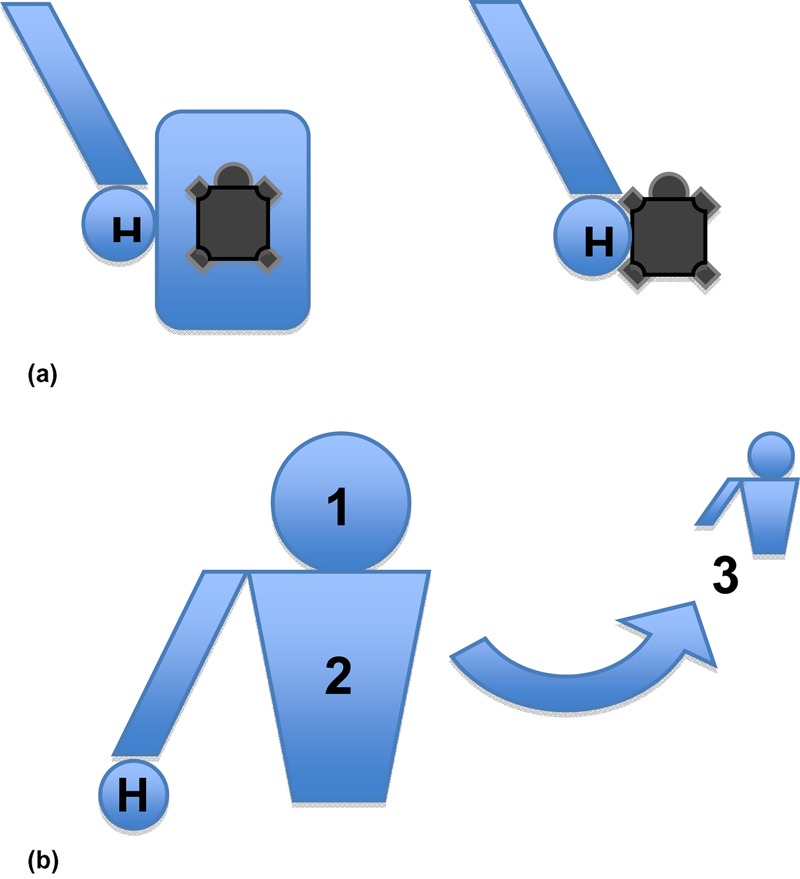

Each investigator engaged in five minutes of observation at a location (e.g. a trader stall) and noted all visitor contact behaviours. Figures 1a and 1b outline the mode of contact observation systems. Individuals who handled or otherwise touched animals were noted as ‘direct’ contact events and those who touched proximal inanimate intermediary surfaces were noted as ‘indirect’ contact events with a presumed contaminated source. Both direct and indirect contact events were further observed to establish whether they subsequently touched their own head (‘hand to head including mouth’ = ‘H1’), body (‘hand to body or clothes’ = ‘H2′) or other person (hand to another person = ‘H3’). Results were marked on preprinted tables under categories of ‘Direct’, ‘Indirect,’ ‘H1′, ‘H2′ and ‘H3′, and tallied after each five-minute observation period. Hygiene efforts (referring to intentional efforts of a person to sanitize their hands or related action) were recorded (not tabulated) by observing whether or not individuals attempted to, for example, clean their hands immediately after contact with a presumed contaminated source.

Figure 1.

(a) Initial mode of contact observation system. H = hand; left = indirect contact with an animal (e.g. with container, table, seller); right = direct contact with/handling of an animal. (b) Subsequent mode of contact observation system. H = hand (+contact): H1 = observed contact between hand and head (inc mouth); H2 = observed contact between hand and body or clothes; H3 = observed contact between hand and another individual

Results

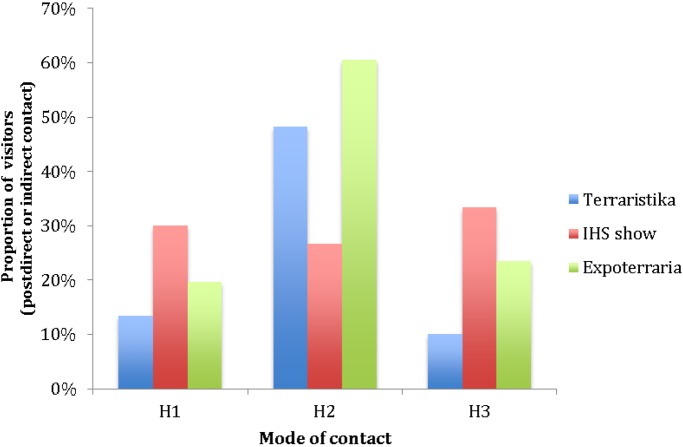

For all three markets, a total of 813 public visitors were observed as they attended vendor stalls. Of these, 29 (3.6%) made direct contact with an animal and 222 (27.3%) made indirect contact with a presumed contaminated source (Table 1). The proportion of these visitors that engaged in subsequent modes of contact was 18.7% hand to mouth (H1), 52.2% hand to body (H2) and 19.9% person to person (H3). Figure 2 provides the breakdown of these contact behaviours for each of the three markets visited.

Table 1.

The number of visitors to vendors observed at three European markets and the proportion that engaged in direct and indirect contact with presumed contaminated sources

| Mode of contact | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total number of visitors* | Direct | Indirect |

| 813 | 29 (3.6%) | 222 (27.3%) |

*Cumulative total of visitors to vendors recorded during five minutes observation periods

Figure 2.

The proportion of visitors to vendors at each market making subsequent modes of contact having initially contacted a presumed contaminated source. H1 = observed contact between hand and head (inc mouth); H2 = observed contact between hand and body or clothes; H3 = observed contact between hand and another individual

This pattern of behavior was broadly consistent between markets with the majority of observed visitors to vendors making indirect contact with animals through touching housing, tables, sellers, money and other merchandize associated with vendors or animals.

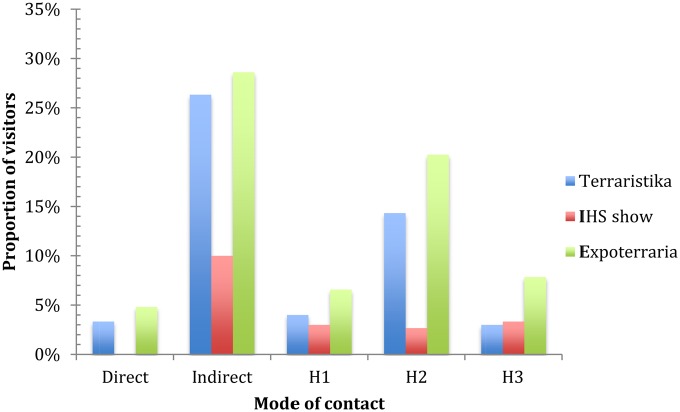

The proportion of visitors to vendors that engaged in contact behaviours at each of the markets is illustrated in Figure 3. The patterns of contact were similar between each of the larger events (Terraristika and Expoterraria); however, at the IHS Show, during the five-minute observation periods, no direct contact with animals was seen.

Figure 3.

Public health and visitor behaviour at three European markets. The total number of observed visitors was 813 (395 at Expoterraria; 300 at Terraristika; 118 at the IHS Show). Direct = direct contact with an animal; Indirect = indirect contact with an animal (e.g. with container, table, seller). H1 = observed contact between hand and hand (inc mouth); H2 = observed contact between hand and body or clothes; H3 = observed contact between hand and another individual

We again emphasize that these data were acquired during numerous five-minute observation periods (a total of 195 minutes of observation) and as such, they provide ‘snapshots’ of general conditions. Therefore, other relevant additional behaviours may occur that were not observed and recorded.

Person-to-person contamination is likely to rapidly increase its representation as presumed contaminated attendees move around a venue and readily form incidental contacts with a large number of people.

Discussion

Our observations indicate that opportunities for direct and indirect contact at pet markets with presumed contaminated animals and inanimate items constitute a significant and major public health concern. Our view is that these public health risks are unresolvable, given the format of the market environment. Furthermore, the ‘exhibition’ nature of these events attracts families with young children, including toddlers and infants (less than 1 year of age).

We consider that the five-minute static observation period for target activities was sufficient for assessment of potential microbial contamination and transference. Target activities were noted within the five-minute period, and indeed a shorter observation period may have been as informative. However, a longer static observation period would unlikely have been more informative because the general throughput of the public arriving at, inspecting and then leaving each seller stall frequently occurred within a five-minute period. Mobile observation periods that involve monitoring the actions of people moving through the venues may have been additionally informative in revealing certain incidental contacts, although given the relatively crowded nature of the events, these additional contacts may reasonably be presumed to occur without specific observation.

Conclusions

The established nature of amphibians and reptiles as a reservoir of potentially pathogenic zoonotic agents implies that all animals, their containers, seller facilities and the sellers themselves must be regarded as sources of potential contami-nation. The direct and indirect actions and interactions between public attendees and sellers are manifestly capable not only of resulting in acquired infection among attendees, but also of disseminating pathogens among the public and all publicly accessible intermediary surfaces. Indeed, we postulate that it would be reasonable to conclude that within a relatively brief period, all public attendees potentially may be subjected to some level of contamination on their person, whether or not that contamination becomes associated with any episode of disease involving themselves or others.

It is also highly unlikely that any method of hygiene control could be practicably implemented in the context of a pet market. Even if comprehensive disinfectant surgical scrub areas were provided with appropriate guidance on contaminant elimination from hands, then this would not offer a reliable solution. Contaminated areas other than hands would remain, and re-contamination of hands and other areas from clothes, people and the environment would likely rapidly re-occur once the person returned to the generalized areas of the pet market and its multifactorial contamination sources. Contamination of clothes and hair, for instance, would also represent a robust contamination source that would persist even after leaving a market and regardless of any hand cleansing.

Hand sanitizer products such as gels and sprays for the prevention of infection were infrequently adopted at the visited events and, where present, were utilized in a less than thorough manner which itself represents a poor form of hygiene management. As indicated earlier, hand sanitizer products used do not offer comprehensive protection, and their promotion may encourage misplaced public confidence in an unreliable method. Such over-reliance is likely to lead to complacent behavior, infection and re-infection.

The situating of pet markets in venues often used for general public purposes, such as school halls and leisure centres, constitutes a potential public health hazard that realistically may endure for days, weeks or months following the conclusion of the pet market. Certain bacteria, such as Salmonella, are well understood to viably persist on surfaces in the general environment. At venues hosting pet markets it is reasonable to presume that all public contact surfaces such as door handles, floors, doorways, walls, light switches and many others may remain microbially contaminated and thus potential sources of infection. Given that these same venues may be sequentially used for a wide variety of other public purposes, including schooling of children, there exists an ongoing potential residual risk of infection to entirely unsuspecting and unprepared users. Furthermore, these venues are often located adjacent to shopping centres which market visitors may attend, carrying with them a host of pathogens and the potential to spread disease far beyond the source of original contamination. As such, even non-attendance at a pet market does not guarantee that public health is not compromised.

Although local authorities in the UK frequently disallow pet markets, numerous events still occur due to lack of enforcement. In the rest of Europe, pet markets are currently legal and common.

Recommendations

We recommend that:

The UK strongly improves its vigilance towards pet market emergence within their jurisdiction and robustly enforces a ban on these events;

The EU in general pursue a policy of prohibition on wildlife (pet) markets within its boundaries, to cover all biological classes of animal including vertebrates and invertebrates;

The UK, and the EU in general, compile a database of all known pet markets and their historical venues within its boundaries and makes this database available for enforcement authorities to ensure local compliance with all prohibitive measures.

DECLARATIONS

Competing interests

None declared

Funding

This work was funded by the Animal Protection Agency (UK), Animal Public (Germany), Eurogroup for Animals (Belgium), Eurogroup for Wildlife and Laboratory Animals (Belgium), Fundaciónpara la Adopción, el Apadrinamiento y la Defensa de los Animales (Spain), International Animal Rescue (UK) and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Germany)

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study: the study involved entirely noninvasive observations of anonymous members of the public at open public events

Guarantor

CW

Contributorship

All authors contributed equally

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Katie Timmins, Elise Geissler and Lia Richter for their contributions by translating key documents from German to English. Eurogroup for Wildlife and Laboratory Animals gratefully acknowledges funding support from the Directorate-General for the Environment of the European Commission. The comments of the reviewers were helpful and appreciated

Reviewer

Ray Greek, Julia Greig

Appendix A

Major amphibian and reptile borne zoonotic infections and infestations. Derived from: (1) Pathogens as bio-weapons, Frye F L, unpublished.22 (2) Zoonoses: drawing the battle lines, Warwick C, Clinical Veterinary Times, 2006.1 (3) Reptile and amphibian communities in the United States, Bridges V, Kopral C, Johnson R, Centers for Epidemiology and Animal Health, 2001.23

| Disease/condition | Genus of pathogen | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Campylobacteriosis | Campylobacter | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Endemic relapsing fever | Borrelia | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Gastroenteritis | Staphylococcus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Campylobacter | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Clostridium | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Escherichia | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Yersinia | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Shigella | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Salmonellosis | Salmonella | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Streptococcosis | Streptococcus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Yersiniosis | Yersinia | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Septicaemia | Acinetobacter | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Alcaligenes | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Bacteroides | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Clostridium | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Citrobacter | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Corynebacterium | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Enterobacter | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Enterococcus | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Fusobacterium | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Klebsiella | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Moraxella | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Morganella | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Pasturella | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Peptococcus | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Proteus | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Pseudomonas | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Salmonella | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Serratia | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Staphylococcus | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Streptococcus | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Viral | Hepatitis A | Picornavirus | Amphibian |

| Western encephalitis | Togaviridus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| West Nile virus | Flaviviridus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Mycotic | Coccidiomycosis | Coccidioides | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Cryptococcosis | Cryptococcus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Septicaemia | Candida | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Cladoorium | Aergillus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Curvularia | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Fusarium | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Rhodotorula | Amphibian, Reptile | ||

| Microparasitic | Amoebiasis | Entamoeba | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Cryptosporidiosis | Cryptosporidium | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Macroparasitic | Diphyllobothriasis | Diphyllobothrium | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Dracunculosis | Dracunculus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Fascioliasis | Fasciola | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Larva migrans | Gnathastoma | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Loaiasis | Loa | Amphibian, Reptile |

Appendix B

Minor amphibian and reptile-borne zoonotic infections and infestations. Derived from: (1) Pathogens as bio-weapons, Frye F L, unpublished.22 (2) Zoonoses: drawing the battle lines, Warwick C, Clinical Veterinary Times, 2006.1 (3) Reptile and amphibian communities in the United States, Bridges V, Kopral C, Johnson R, Centers for Epidemiology and Animal health, 2001.23

| Disease | Genus of pathogen | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial | Vibriosis | Vibrio | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Melioidosis | Burkholderia | Amphibian | |

| Mycoplasmosis | Mycoplasma | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Mycobacteriaiosis | Mycobacterium | Amphibian | |

| Streptothricosis | Dermatophilus | Reptile | |

| Viral | California encephalitis | Bunyaviridae | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Mycotic | Adiaspiromycosis | Chrysosporium | Amphibian |

| Microparasitic | Balantidiasis | Balantidium | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Echinostomiasis | Echinostoma | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Giardiasis | Giardia | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Paragonimiasis | Paragonimus | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Rhinosporidiosis | Rhinosporium | Reptile | |

| Sarcocystis | Sarcocystis | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Macroparasitic | Ancylostomiasis | Ancylostoma | Amphibian, Reptile |

| Chigger mite dermatitis | Eutombicula | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Dwarf tapeworm infestation | Hymenolepis | Amphibian, Reptile | |

| Thelaziasis | Thelazia | Amphibian, Reptile |

References

- 1.Warwick C Zoonoses: drawing the battle lines. Vet Times 2006;36:26–8 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warwick C, Lindley S, Steedman C Signs of stress. Env Health News 2011;10:21, Chartered Institute for Environmental Health [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krauss H Zoonoses: Infectious Diseases Transmissible from Animals to Humans. Washington, VA: ASM Press, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geue L, Löschner U Salmonella enterica in reptiles of German and Austrian origin. Vet Microbiol 2002;84:79–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karesh W, Cook RA, Gilbert M, Newcombe J Implications of wildlife trade on the movement of avian influenza and other infectious diseases. J Wildlife Dis 2007;43(Suppl.):55–9 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward L Salmonella perils of pet reptiles. Commun Dis Public Health 2000;3:2–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mermin J, Hutwagner L, Vugia D, et al. Reptiles, amphibians, and human Salmonella infection: a population-based, case-control study. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:253–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgos S, Burgos SA Influence of exotic bird and wildlife trade on avian influenza transmission dynamics: animal-human interface. Int J Poultry Sci 2007;6:535–8 [Google Scholar]

- 9.HPA zoonoses network newsletter 2009, 4 April

- 10.Karesh W, Cook RA, Bennett EL, Newcombe J Wildlife trade and global disease emergence. Emerg Infect Dis 2005;1:1000–2, Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown C Emerging zoonoses and pathogens of public health significance – an overview. Rev Sci Tech 2004;23:435–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chomel BB, Belotto A, Meslin FX Wildlife, exotic pets and emerging zoonoses. CDC Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:6–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warwick C, Toland E, Glendell G Why legalise exotic pet markets? Vet Times 2005;35:6–7 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warwick C, Lambiris AJL, Westwood D, Steedman C Reptile-related salmonellosis. J R Soc Med 2001;93:124–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warwick C, Arena PC, Steedman C, Jessop M A review of captive exotic animal-linked zoonoses. J Env Health Res 2012;12:9–24, Chartered Institute for Environmental Health [Google Scholar]

- 16.Friedman CR, Torigian C, Shillam PJ, et al. An outbreak of salmonellosis among children attending a reptile exhibit at a zoo. J Pediatr 1998;132:802–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamm SH, Taylor A Jr, Gangarosa EJ, et al. Turtle-associated salmonellosis, I: An estimation of the magnitude of the problem in the United States, 1970–1971. Am J Epidemiol 1972;95:511–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frye FL Salmonellosis. Reptilian 1995;3:1 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mermin J, Hoar B, Angulo FJ Iguanas and Salmonella marina infection in children: a reflection of the increasing incidence of reptile-associated salmonellosis in the United States. Pediatrics 1997;99:399–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warwick C, Lindley S, Steedman C How to handle pets: a guide to the complexities of enforcing animal welfare and disease control. Env Health News 2011;8:18–9 Chartered Institute for Environmental Health [Google Scholar]

- 21.Altherr S, Brückner J, Mackensen H Missstände auf Tierbörsen (2010) MangelhafteUmsetzung der BMELV-Tierbörsen-Leitlinien – EineBestandsaufnahme, ProWildlife, Germany, 2010, 84 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frye FL. Pathogens as bio-weapons. Unpublished.

- 23.Bridges V, Kopral C, Johnson R Reptile and amphibian communities in the United States, Centers for Epidemiology and Animal Health, 2001, 36 See http://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/emergingissues/downloads/reptile.pdf (last accessed 9 August 2012) [Google Scholar]