Abstract

This study sought to determine the synergistic effects of age and HIV infection on medical co-morbidity burden, along with its clinical correlates and impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) across the lifespan in HIV. Participants included 262 individuals across four groups stratified by age (≤40 and ≥50 years) and HIV serostatus. Medical co-morbidity burden was assessed using a modified version of the Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI). Multiple regression accounting for potentially confounding demographic, psychiatric, and medical factors revealed an interaction between age and HIV infection on the CCI, with the highest medical co-morbidity burden in the older HIV+cohort. Nearly half of the older HIV+group had at least one major medical co-morbidity, with the most prevalent being diabetes (17.8%), syndromic neurocognitive impairment (15.4%), and malignancy (12.2%). Affective distress and detectable plasma viral load were significantly associated with the CCI in the younger and older HIV-infected groups, respectively. Greater co-morbidity burden was uniquely associated with lower physical HRQoL across the lifespan. These findings highlight the prevalence and clinical impact of co-morbidities in older HIV-infected adults and underscore the importance of early detection and treatment efforts that might enhance HIV disease outcomes.

Introduction

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, approximately 30% of persons living with HIV (PLWH) in the United States in 2008 were 50 years of age or older.1 However, knowledge regarding this growing cohort of older PLWH may be suboptimal amongst medical providers specializing in geriatrics and gerontology,2 which is a significant concern, given the a notable shift in the epidemiology of HIV infection since the era before combination antiretroviral therapy (cART); in fact, the prevalence of older HIV-infected adults is expected to double in the coming decade.3 Age confers increased vulnerability towards more rapidly advancing HIV disease,4 including higher risk of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders,5 AIDS-defining illness,6 and mortality,7 which may be driven by a variety of factors not limited to delayed diagnosis, immune senescence, and differential response to cART.8,9 Consequently, older PLWH are at sharply increased risk of poorer everyday functioning outcomes and HIV-related disability.10 Thus, the rapidly expanding size of this particularly vulnerable and understudied cohort of older PLWH underscores the need for identifying potentially modifiable clinical factors that influence health outcomes and quality of life in an effort to stem the invariable rise in health care resource demands in the coming decade.11

In that regard, there has been increasing attention to the possible role of medical co-morbidity burden in the poorer health outcomes observed in older PLWH. In fact, the new conceptual model of aging with HIV infection proposed by the HIV and Aging Working Group of the NIH Office of AIDS Research posits that medical co-morbidities are seen earlier and more frequently in older PLWH, which leads to frailty, neurocognitive and functional impairment, organ system failure, and increased hospitalization.11 Across the lifespan, HIV is associated with increased rates of co-morbidities such as hepatitis C co-infection12 and metabolic syndrome13 that heighten risks of adverse cognitive13,14 and health-related outcomes (e.g., chronic liver disease progression12). As PLWH grow older, they also become more susceptible to developing the physical and mental diseases associated with so-called “normal” aging. For example, older PLWH have higher prevalence of multimorbidity,15 including cardiovascular complications such coronary artery disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and diabetes,16,17,18 as well as cancer and diseases of liver, kidney, bone (e.g., ostopenia), and nervous system.19 Older PLWH may also acquire these co-morbidities earlier in life relative to their seronegative counterparts: Guaraldi et al.20 reported that the prevalence of multimorbidity (which indicates ≥2 noninfectious co-morbidities) among 41- to 50-year-old PLWH was comparable to that of seronegatives who were a decade older (i.e., 51–60 years of age). Similarly, Oursler et al.21 reported that amongst HIV-infected and uninfected patients with pulmonary disease, PLWH experienced poorer functioning relative to seronegative individuals; In fact, a 50-year-old PLWH was functionally equivalent to a 68-year-old seronegative individual,21 which further supports the role of HIV in possibly accelerating both the prevalence and onset of co-morbid conditions.

Nevertheless, there have been very few studies that have directly evaluated the synergistic effects of age and HIV on co-morbidity burden using appropriate comparison groups, thereby leaving questions about the unique and combined effects of these two increasingly intersecting risk factors. In one of the first such studies, Goulet et al.22 reported interactions between HIV and older age for diabetes, vascular disease, liver disease, and substance use disorders in the Veterans Aging Cohort Study (VACS), with the highest rates in older PLWH. Guaraldi and colleagues20 reported significantly elevated rates of multimorbidity, including cardiovascular disease, renal failure, bone fractures, and diabetes, in older PLWH as compared to demographically comparable seronegatives in Italy. In terms of the clinical correlates of co-morbidity burden in older PLWH, a handful of studies have identified associations with lower CD4 cell counts,20,22–24 higher HIV RNA levels in plasma,22–24 cART interruption,25 and injection drug use.24 The everyday impact of higher co-morbidity burden among older PLWH is also not well understood, though a few studies have suggested that such burden might increase the risk of clinician-rated disability and unemployment.10,21

Thus, the existing literature suggests that older PLWH experience greater risk of multimorbidity and co-morbidity burden, which may be associated with poorer immunnovirologic functioning and injection drug use. The present study seeks to extend this literature by: (1) using a factorial design to determine the synergistic effects of older age and HIV infection on co-morbidity burden in a well-characterized cohort matched on demographics (e.g., education, premorbid IQ) and substance use histories who underwent comprehensive sociodemographic, psychiatric, cognitive, and medical research evaluations; (2) determining the clinical correlates of co-morbidity burden in both younger and older PLWH; (3) measuring co-morbidity burden with a standardized, weighted, and widely validated summary index (i.e., Charlson Co-morbidity Index); and (4) characterizing the association between co-morbidity burden and health-related quality of life in both younger and older PLWH.

Methods

The study protocol was approved by the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) human research protections program. Each participant provided written, informed consent, and was administered a comprehensive medical, psychiatric, and neuropsychological medical evaluation.

Participants

Participants included 262 individuals enrolled in an NIMH-sponsored study on the effects of aging and HIV on memory functioning, which was housed at the UCSD HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP). Participants were recruited from local HIV clinics and from the general community. HIV serostatus was confirmed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays, along with a Western blot test. Consistent with prior research in HIV,27 age group classifications were defined as: younger (i.e., age ≤40 years old) and older (i.e., age ≥50 years old). This approach yielded four study groups, including younger HIV- (n=56), older HIV-(n=65), younger HIV+(n=50), and older HIV+(n=91).

Participants were excluded if they had histories of severe psychiatric (e.g., schizophrenia) or neurological conditions (e.g., seizure disorders, closed head injuries with a loss of consciousness greater than 15 min, central nervous system neoplasms, or opportunistic infections) or if they met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV28) criteria for current (i.e., within the past 30 days) substance use disorders (i.e., abuse or dependence) as determined by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, Version 2.1).29 The CIDI is a semi-structured computer-assisted interview for the assessment of psychiatric and substance use disorders using DSM-IV criteria that was administered by certified research associates and has been widely used in HIV research.27 To confirm recent abstinence from alcohol and drugs, a urine toxicology test for illicit drugs (except marijuana) and Breathalyzer were used for screening on the day of evaluation. Due to the aims of the parent study, which were focused on the neurocognitive impact of aging with HIV infection, participants with a verbal IQ estimate <70 based on Wechsler Test of Adult Reading30 were also excluded. Demographic characteristics of the participants are displayed in Table 1. The study groups were comparable for most demographics (e.g., education, sex, estimated premorbid IQ; p>0.10). However, the two younger groups had higher proportions of ethnic minorities relative to the two older samples (p<0.05; See Table 1 for more detail regarding proportions of ethnic minorities within the study groups). Self-reported sexual orientation was gathered via structured interview and is also reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, Neuropsychiatric, Medical, and HIV-Disease Characteristics of the Four Study Groups

| |

HIV− |

HIV+ |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Young n=56 | Old n=65 | Young n=50 | Old n=91 | pa |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age (years) | 29.1 (5.8) | 56.0 (4.9) | 30.9 (4.8) | 56.7 (5.3) | – |

| Education (years) | 13.6 (2.0) | 14.0 (2.7) | 13.2 (2.1) | 13.8 (2.2) | 0.254 |

| Sex (% male) | 69.6 | 70.8 | 82.0 | 81.3 | 0.200 |

| Ethnicity | 0.004 | ||||

| Caucasian (%) | 44.6 | 66.2 | 42.0 | 69.2 | |

| Hispanic (%) | 30.3 | 15.4 | 24.0 | 9.9 | |

| African American (%) | 21.4 | 16.9 | 28.0 | 19.8 | |

| Other (%) | 3.6 | 1.5 | 6.0 | 1.1 | |

| Sexual orientation | <0.001 | ||||

| Homosexual (%) | 16.7 | 23.4 | 62.0 | 60.2 | |

| Heterosexual (%) | 81.5 | 73.4 | 28.0 | 28.4 | |

| Bisexual (%) | 1.9 | 3.1 | 10.0 | 11.4 | |

| Estimated VIQ | 101.5 (9.9) | 103.7 (11.0) | 99.3 (10.7) | 101.8 (11.4) | 0.205 |

| Neuropsychiatric characteristics | |||||

| POMS Totalb | 32.5 (22.0, 53.8) | 36.0 (24.0, 56.0) | 37.5 (25.8, 70.3) | 51.0 (33.0, 78.0) | 0.001 |

| Current MDD (%) | 3.6 | 1.5 | 12.0 | 12.1 | 0.019 |

| Lifetime MDD (%) | 30.4 | 44.6 | 56.0 | 56.0 | 0.011 |

| Lifetime substance dependence (%) | 42.9 | 50.8 | 46.0 | 51.7 | 0.720 |

| HDS T-scoreb | 43.8 (12.5) | 41.5 (14.8) | 38.6 (13.2) | 36.7 (15.1) | 0.019 |

| SF-36 totalb | 69.0 (8.4) | 66.9 (9.6) | 65.5 (11.5) | 59.1 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Medical characteristics | |||||

| Hepatitis C virus (%) | 3.6 | 16.9 | 4.0 | 34.1 | <0.001 |

| Number of medicationsb | 0.0 (0.0, 0.8) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.5) | 4.0 (3.0, 6.0) | 8.0 (5.0, 12.0) | <0.001 |

| Non-ARVsb | 0.0 (0.0, 0.8) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.5) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 5.0 (2.0, 8.0) | <0.001 |

| ARVsb | – | – | 3.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 4.0 (3.0, 4.0) | 0.067 |

| HIV disease characteristics | |||||

| Duration of infection (years)b | – | – | 4.3 (2.4, 8.7) | 17.7 (13.8, 21.2) | <0.001 |

| CD4 nadir (cells/μl)b | – | – | 248.5 (178.8, 366.0) | 148.0 (54.0, 275.0) | 0.001 |

| Current CD4 (cells/μl)b | – | – | 553.0 (419.5, 759.0) | 545.0 (384.0, 810.0) | 0.924 |

| Plasma VL (% detectable) | – | – | 26.0 | 13.6 | 0.075 |

| CSF VL (% detectable) | – | – | 21.4 | 15.6 | 0.449 |

| AIDS (%) | – | – | 32.0 | 64.9 | <0.001 |

| ARVs (%) | – | – | 88.0 | 92.3 | 0.324 |

| ACTG adherence (% adherent) | – | – | 95.5 | 96.4 | 0.787 |

Data represent means (SD) unless otherwise noted.

p Value reflects omnibus group difference.

Median (interquartile range).

AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; ARVs, antiretrovirals; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; HDS, HIV Dementia Scale; MDD, major depressive disorder; POMS Total, Profile of Mood States, total mood disturbance score; SF-36 Total, RAND 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, general summary score; VIQ, verbal IQ (based on the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading); VL, viral load.

Measurement of medical co-morbidity burden

Medical co-morbidity burden was quantified using the Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI), which was selected because it: (1) was compatible with the available study data; (2) has strong construct validity, reliability and feasibility;31 and (3) has been used in previous studies examining PLWH.32–34 The CCI accounts for 19 co-morbidities, each assigned a weight based on the adjusted 1-year mortality risk as determined by Charlson et al.35 We excluded AIDS as a co-morbidity due to the inherent bias that would result as a function of our study group definitions (i.e., HIV+ versus HIV-), and its arguably outdated co-morbidity burden (CMB) weight in the era of cART.36 A CCI was generated for each individual participant, blinded to HIV and age status by matching the ICD-9-CM codes derived from the standardized neuromedical and neuropsychological research examinations (detailed below) with each co-morbidity as reported by Deyo et al.37 For this study, CCI coding of “dementia” was adjusted to account for the recent decrease in the prevalence rates of HIV-associated dementia (HAD)38 and increase in the rates of milder forms of cognitive impairment in HIV infection.39 Specifically, participants were given a weight of “1” if they were classified as having both neurocognitive impairment (NPI) and related functional declines, which is a classification that corresponds roughly to a diagnosis of mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) in HIV infection.40

Medical evaluation

Each participant had a standardized medical history interview, structured neurological and medical examination, as well as collection of blood, cerebrospinal fluid, and urine samples consistent with previous studies that have been conducted through the UCSD HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP; e.g., Heaton et al.39). All medical history interviews were conducted by trained research staff and the examinations performed by clinicians (RN, NP, or MD). Medical history questionnaires completed by the participants were used as a guide during the medical interview process to complete case report forms evaluating past medical history, HIV disease stage, antiretroviral use history, current medications, and pertinent review of systems. While the majority of medical history data was collected via self-report, additional data and/or clarifications were collected utilizing medical records as available. For data on current medications, participants were asked to bring all prescribed medications or a medication list to their study visits. All antiretroviral (ARV) and concomitant medications were recorded at each visit (name, daily dose, dose units, frequency and start date). These medications were divided into ARV and non-ARV medications. Number of ARV medications includes each antiretroviral component regardless of formulation (e.g., the combination medication Truvada is counted as two ARVs: emtricitabine and tenofovir). Number of non-ARV medications includes all concomitant medications except those taken on an as needed basis. Current blood CD4 cell counts were measured by flow cytometry and HIV RNA concentrations in both plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were assayed by ultrasensitive (lower limit of detection, 50 copies/mL) reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Amplicor®, Roche Diagnostic Systems, Indianapolis, IN). Co-morbid medical diagnoses, current medications, antiretroviral history, and HIV disease characteristics (except for current CD4 and HIV RNA) were self-reported. Current blood CD4 cell counts were measured by flow cytometry, and HIV RNA concentrations in both plasma and CSF were assayed by ultrasensitive (lower limit of detection, 50 copies/mL) reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (Amplicor®).

Medical and HIV-disease related characteristics are presented in Table 1. The older HIV+group had a greater proportion of individuals infected with HCV relative to their older HIV- counterparts, and both older groups had larger proportions relative to the younger groups (p<0.05). With regard to HIV-disease characteristics, the older HIV+group had a longer duration of infection, lower nadir CD4 counts, a greater proportion of individuals diagnosed with AIDS (p<0.05), and a slightly lower proportion of individuals with detectable plasma HIV viral load (p=0.075) relative to the younger HIV+ group. The two HIV+groups were comparable for current CD4 count, as well as proportions of individuals on antiretroviral (ARV) therapy or with detectable CSF HIV viral load (p>0.10). Each HIV-infected participant was also administered the ACTG Adherence to Anti-HIV Medications questionnaire, a self-report measure designed to assess cART adherence (e.g., how many pills missed and why) over the 4 days prior to their assessment. Participants were classified as “poor adherers” if they missed one or more doses in the past 4 days. The older and younger HIV+groups did not differ in regards to ARV adherence (p>0.10; see Table 1).

Neuropsychological evaluation

Participants were administered the reading subtest of the Weschler Test of Adult Reading30 as an index of pre-morbid cognitive functioning, and the HIV Dementia Scale (HDS) alongside a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery designed to assess cognitive domains most commonly affected in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND)40 including executive functions, attention/working memory, episodic learning and memory, verbal fluency, information processing speed, and motor skills (see Woods et al.42 for details). Clinical ratings ranging from 1 (above average) to 9 (severely impaired) were assigned to each individual cognitive domain by a neuropsychologist (SPW) using published, standardized, and well-validated procedures42 and used to determine the presence or absence of global neuropsychological impairment (NPI). A cut-point of 5 or greater was used as an indicator of global NPI.

To determine whether the observed NPI was “syndromic”, participants also completed a modified form of the Lawton and Brody43 Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Scale, which has been used previously in the HIV literature as an index of daily functioning abilities.44,45 This self-report measure requires the participant to rate his/her current and best ability to independently perform various basic (e.g., dressing) and instrumental (i.e., medication and financial management, housekeeping, grocery shopping, cooking, transportation, shopping, laundry, telephone use, and home repairs) activities of daily living (BADLs and IADLs, respectively). As this study was primarily concerned with the ability to carry out higher-order everyday activities, only IADL items were used for classification purposes and analyses45. Individuals were classified as IADL dependent if they reported a decline from their best level of functioning in their ability to carry out two or more functional tasks.44,45 As noted above, this IADL variable was used to derive a weighted “syndromic NPI” variable for inclusion into the CCI, whereby individuals received a weight of “1” if they were classified as having both global NPI and IADL dependence.

Psychiatric evaluation

The current mood (i.e., covering the past week) of each participant was assessed using the Profile of Mood States (POMS),46 which is a 65-item, self-report measure of current affective distress. Current (within the last 30 days) and lifetime (LT) major depressive disorder (MDD) and lifetime substance use disorders were assessed using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview.29 Psychiatric and substance use diagnoses for the study groups are presented in Table 1. The older HIV+group reported greater current affective distress on the POMS (i.e., Total Mood Disturbance) relative to the two HIV- study groups (p<0.05), but did not differ from their younger HIV+counterparts (p=0.279). Current rates of MDD amongst the older HIV+group were significantly higher than the older HIV- group (p=0.007) and slightly higher than that of the younger HIV- group (p=0.061), though were comparable to that of the younger HIV+group (p>0.10). Lifetime rates of MDD within the older HIV+group were significantly greater relative to the younger HIV- group (p=0.002), though they did not differ relative to the older HIV- or younger HIV+groups (p>0.10). The study groups had similar rates of lifetime substance dependence disorders (p=0.720).

Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life

Each participant also completed the RAND 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), which is a disease nonspecific 36-item self-report questionnaire designed to assess aspects of physical and mental health well-being, and has been validated in HIV as an index of health-related quality of life (HRQoL).47,48 The overall SF-36 score (General Summary Score) is composed of two main summary scores (the Physical and Mental Health-Related Quality of Life subscales), which in turn are comprised of 4 subscales each, and range from 0 to 100 where higher scores indicate better HRQoL. The Physical Functioning (PF), Role-Physical (RP; i.e., role limitations due to physical problems), Bodily Pain (BP), and General Health (GH) subscales comprise the Physical Health summary measure, and the Vitality (VT), Social Functioning (SF), Role-Emotional (RE; i.e., role limitations due to emotional problems), and Mental Health (MH) subscales comprise the Mental Health summary score. Continuous Physical and Mental HRQoL summary scores were used for analyses.

Results

Shapiro-Wilk W-test showed that CCI was not normally distributed (p<0.001), so nonparametric statistics (e.g., Spearman's rho) were used whenever possible. In the multivariable models for which alternate nonparametric approaches were not readily available or easily interpretable, a review of the residuals revealed no major departures from normality. All statistical analyses were performed using JMP 9.0.2 software (SAS Institute, Carey). Hedges' g was used for effect size estimates and a critical alpha level of 0.05 was used for all analyses.

Age and HIV effects on the CCI

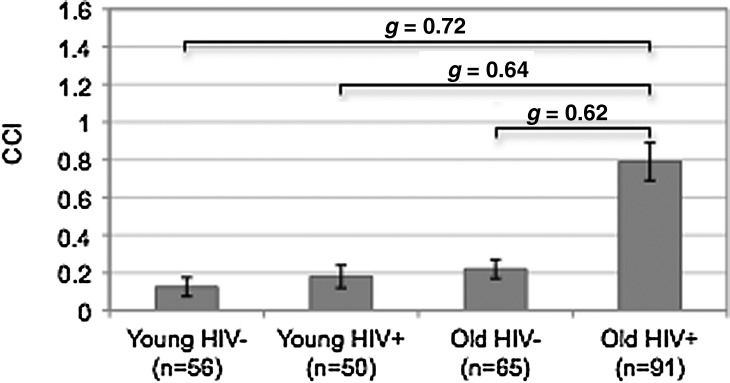

A multiple linear regression was used to explore the main and interactive effects of age and HIV infection on the CCI (Table 2), while accounting for potentially confounding variables that differed between the four study groups (i.e., ethnicity, HCV, POMS Total Mood Disturbance, and sexual orientation). The overall regression model predicting the CCI was significant [F(7,248)=8.82, Adjusted R2=0.18, p<0.001]. Analysis revealed a significant interaction between age and HIV (Estimate=0.46, p=0.005). Specifically, a significantly higher CCI was observed in the older HIV+ group relative to each of the remaining study groups (ps<0.001; Fig. 1), even when accounting for the aforementioned potentially confounding variables. The proportions of individual CCI conditions across the study groups in order of frequency in older HIV+ group are displayed in Table 3.

Table 2.

Multiple Regression Analyses Demonstrating Effects of HIV Infection and Aging on the Charlson Co-Morbidity Index (CCI)

| Adjusted R2 | F | Estimate | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI) | 0.18 | 8.83 | <0.001a | |

| Age group [old] | 0.03 | 0.780 | ||

| HIV status [HIV+] | −0.01 | 0.968 | ||

| HIV status [HIV+]a age group (old) | 0.46 | 0.005a | ||

| Covariates | ||||

| Ethnicity [Caucasian] | 0.03 | 0.751 | ||

| Hepatitis C virus (HCV+) | 0.27 | 0.019a | ||

| POMS total | 0.00 | 0.037a | ||

| Sexual orientation (heterosexual) | −0.05 | 0.605 | ||

Denotes significance at p<0.05.

CCI, Charlson Co-morbidity Index; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; POMS, Profiles of Mood States.

FIG. 1.

Bar chart displaying the interaction of HIV and age on the Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI). All p values<0.001.

Table 3.

Proportions of Charlson Co-Morbidity Index (CCI) Conditions Across Study Groups in Order of Frequency Within the Older HIV+ Group

| |

HIV− |

HIV+ |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Young n=56 | Old n=65 | Young n=50 | Old n=91 | pa |

| Charlson Co-morbidities (%) | |||||

| Diabetes | 0.0 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 17.8 | <0.001 |

| Syndromic NPI | 0.0 | 1.5 | 4.0 | 15.4 | <0.001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 9.1 | 7.6 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 0.777 |

| Malignancy, includes leukemia and lymphoma | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.9 | <0.001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 1.8 | 3.0 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 0.930 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.234 |

| Mild liver disease | 1.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.313 |

| Myocardial infarction | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.234 |

| Renal disease | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.2 | 0.234 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 0.546 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.0 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.133 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – |

| Moderate to severe liver disease | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – |

| Rheumatologic disease | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.426 |

p Value reflects omnibus group difference. HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NPI, neuropsychological impairment.

Clinical correlates of the CCI in younger and older HIV-infected individuals

Next, exploratory correlational and regression analyses were conducted within the younger (n=50) and older (n=91) HIV+samples separately in order to identify any of the demographic (e.g., age, education, ethnicity, sexual orientation), psychiatric (e.g., lifetime MDD), medical (e.g., HCV, total number of medications) or HIV-disease (e.g., AIDS status) variables listed in Table 1 that may be associated with the CCI. The CCI was examined as a dichotomous variable in the younger HIV+group due to the severely restricted range of CCI values (i.e., values consisted of only 0 or 1, with 0 indicating no co-morbidities as indexed by the CCI), and as a continuous variable for analyses within the older HIV+ group (range=0, 4). Within the younger HIV+group, only greater current affective distress (i.e., higher POMS Total Mood Disturbance score) was a significantly associated with the CCI (p=0.014). Further examination into the individual POMS subscales revealed significant associations between the CCI and the vigor/activation (p=0.012) and depression/dejection (p=0.045) subscales only. Within the older HIV+group, only detectable HIV RNA plasma viral load emerged as a significant correlate of the CCI (p=0.037), a finding that persisted even when examined alongside ARV use (p=0.030).

Polypharmacy

The total number of non-ARV medications was also evaluated as a possible correlate of the CCI in the younger and older HIV+ groups. No significant relationship was found in the younger HIV+ group (p>0.10), though there was a significant, moderate correlation between total number of non-ARV and the CCI in the older HIV+ group (r=0.24; p=0.02).

Effects of age and the CCI on health-related quality of life in HIV infection

Lastly, correlational and multiple linear regression analyses were conducted within the entire HIV+sample (i.e., younger and older HIV+ groups combined; n=141) in order to explore the main and interactive effects of age and the CCI on aspects of physical and mental HRQoL in HIV (i.e., Physical and Mental HRQoL subscale summary scores), alongside factors that differed between the younger and older HIV+samples (i.e., ethnicity, HCV infection, AIDS status, duration of HIV infection, and sexual orientation; Table 4). Lifetime MDD was also included in the model due to its consistent association with adverse functional outcomes in the HIV literature.44 While the younger and older HIV+ groups also differed on other HIV disease variables (e.g., nadir CD4 count), only AIDS status and duration of HIV infection were included in the models in order to maintain a statistically appropriate number of predictors given our sample size, and to avoid issues of multicolinearity. While related, AIDS status and duration of infection were less strongly associated relative to other pairings of HIV-disease characteristics (e.g., AIDS status and nadir CD4 count). Of note, however, the main findings from our analyses did not change regardless of which HIV-disease variables were included in the models. Significant regression models were observed for both the Physical [F(9,126)=7.36; adjusted R2=0.30; p<0.001] and Mental [F(9,125)=4.65; adjusted R2=0.20; p<0.001] HRQoL subscales. A trend-level age by CCI interaction was observed for the Physical HRQoL subscale (Estimate=6.38, p=0.089), though no significant interaction was observed for the Mental HRQoL subscale (p>0.10). A significant main effect of the CCI was observed for the Physical HRQoL summary score (Estimate=−9.23, p=0.011), though not for the Mental HRQoL summary score (p>0.10), nor were there main effects of age group for either measure (p>0.10). Lifetime MDD was the only other variable that emerged as a significant correlate of the HRQoL measures, and was significantly associated with both the Physical (Estimate=−8.01), and Mental HRQoL summary scores (Estimate=−8.74, ps<0.001). AIDS status was associated with Physical HRQoL though only at trend level (Estimate=−3.15, p=0.072).

Table 4.

Effects of Age and the Charlson Co-Morbidity Index (CCI) on Physical and Mental Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) in the HIV-Infected Sample (n=141)

| Multiple linear regression | Adjusted R2 | F | Estimate | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical HRQoL | 0.30 | 7.36 | <0.001a | |

| Age group [old] | −0.93 | 0.724 | ||

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI) | −9.23 | 0.011a | ||

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI)* age group [old] | 6.38 | 0.089 | ||

| Covariates | ||||

| Ethnicity [Caucasian] | 0.41 | 0.810 | ||

| Hepatitis C virus [HCV+] | −1.17 | 0.577 | ||

| Lifetime MDD [yes] | −8.01 | <0.001a | ||

| AIDS status [AIDS] | −3.15 | 0.072 | ||

| Duration of infection | 0.01 | 0.485 | ||

| Sexual orientation [heterosexual] | −2.20 | 0.200 | ||

| Mental HRQoL | 0.20 | 4.65 | <0.001a | |

| Age group [old] | −2.24 | 0.464 | ||

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI) | −6.30 | 0.135 | ||

| Charlson Co-morbidity Index (CCI)* age group [old] | 3.81 | 0.385 | ||

| Covariates | ||||

| Ethnicity [Caucasian] | −0.92 | 0.643 | ||

| Hepatitis C virus [HCV+] | 0.27 | 0.914 | ||

| Lifetime MDD [yes] | −8.74 | <0.001a | ||

| AIDS status [AIDS] | −2.30 | 0.260 | ||

| Duration of infection | 0.00 | 0.731 | ||

| Sexual orientation [heterosexual] | −0.03 | 0.988 | ||

Denotes significance at p<0.05.

AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CCI, Charlson Co-morbidity Index; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Discussion

As the prevalence of older PLWH has increased, there has been growing concern regarding medical co-morbidity burden in this population characterized by high rates of general and age-related chronic medical conditions and treatments.20,23 Thus, identifying the nature and extent of medical co-morbidity burden in older PLWH, including its clinical and quality of life correlates, is imperative as these factors may have significant functional and public health implications.11 Results of this study extend the prior literature on this topic by demonstrating synergistic effects of older age and HIV on an overall medical co-morbidity burden, which persisted even when accounting for potentially confounding variables that differed amongst the study groups (e.g., ethnicity, current affective distress, and HCV infection). Specifically, the older HIV+group had a significantly higher co-morbidity index with medium effect sizes relative to older HIV- (g=0.62), younger HIV+(g=0.64), and younger HIV- (g=0.72) cohorts. Results are consistent with and extend the aforementioned studies showing that older PLWH are at increased risk for various medical co-morbidities, including vascular disease, diabetes, and liver disease.22 In fact, approximately 50% of our older HIV+group had at least one co-morbid medical condition that was considered for inclusion in the CCI (Fig. 2), which was notably higher than the rates observed in our older HIV-, younger HIV-, and younger HIV-groups (approximately 22%, 18%, and 13%, respectively). Moreover, when the CCI is expanded to include other current co-morbid conditions that are highly prevalent in both HIV and aging populations (i.e., hepatitis C virus and current MDD) and associated with poor health-related outcomes,12,49 rates of at least one co-morbid condition in the older HIV+group increase to approximately 67% (n=61) of the sample, which was again considerably higher than the rates observed in the remainder of the groups (i.e., range 17–32%).

FIG. 2.

Proportions of study participants with unweighted CCI conditions across HIV serostatus and age group.

The most prevalent CCI conditions observed in our older PLWH were diabetes (18%), syndromic neurocognitive impairment (15%), and malignancy (9%). Chronic pulmonary disease was also prevalent in the older HIV+sample, (i.e., approximately 12%), but occurred at a rate that was comparable to the other study groups. Elevated prevalence rates in older PLWH have been previously observed for diabetes/metabolic syndrome,15–17,50 which have often been associated with ARV use. In fact, ARV use has been linked to a wide variety of metabolic complications (e.g., diabetes, hypertension51) that can lead to further complications (e.g., metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease) and may increase non-HIV-related morbidity and mortality.52,53 Non-HIV-related cancers are also common in older HIV-infected adults,15,54 and may be associated with immunodeficiency.55 The elevated prevalence rates of these conditions is alarming given recent increases in the rates of non-AIDS related deaths among older PLWH, which has been closely linked to cardiovascular and pulmonary disease as well as non-AIDS related malignancies.56

Of particular interest is the relatively high prevalence of syndromic NPI among the various co-morbidities in the older PLWH. In this study, we operationalized syndromic NPI as having at least mild global neurocognitive deficits that interfered with daily functioning ability (i.e., akin to a diagnosis of HIV-associated mild neurocognitive disorder). In fact, the older HIV+individuals were over four times more likely to be classified as syndromic relative to their younger counterparts. The proportion of individuals with syndromic NPI in our older HIV+sample (15%) is consistent with the results of a recent large-scale multisite neuroepidemiologic CHARTER study38 that reported a 14% prevalence rate. Of note, global NPI (impairment irrespective of functional impact) was evident in 39% of the older HIV+ group, which is also broadly commensurate with current prevalence estimates.38 This is consistent with recent evidence suggesting that older HIV+ individuals may be particularly vulnerable to cognitive and functional decline.5,10,27,57 Myriad adverse functional consequences have been linked to HIV-associated neurocognitive deficits specifically in older HIV+adults, including poor medication management,58,59 financial difficulties,59 and declines in activities of daily living.10,57 Moreover, older HIV+ adults have high prevalence rates of co-existing conditions (e.g., substance use disorders, mood disorders) that have been established as independent risk factors for neurocognitive impairment (for a review, see Schuster and Gonzalez60) and could further complicate functional outcomes. Collectively, the high proportion of syndromic NPI in older HIV+adults and the strong link between neurocognitive impairment and adverse functional outcomes highlights the importance of early detection and remediation of cognitive impairment in order to improve aspects of everyday living and/or to prevent further disability.

Findings of this study also suggest that there may be differential clinical correlates of medical co-morbidity burden (i.e., CCI) within older and younger PLWH that will be important to consider in the development of preventative and/or treatment measures. In our older HIV+sample, only detectable HIV RNA plasma viral load was significantly associated with the CCI, a finding which persisted even when accounting for ARV use. This is consistent with previous research suggesting an association between medical co-morbidities and viremia.22–24,53 For example, Monroe et al.53 found a significant correlation between viremia and poor control of diabetes and hypertension in HIV-infected individuals. One interpretation of their findings was that poor virologic control leads to chronic inflammation, which is an established cardiovascular risk factor61 and has been associated with poorer immune functioning. Another explanation for their findings, as well as the results of this study, is that the association between detectable viral load and medical co-morbidities in older HIV+adults may be related to poor medication adherence. This is of particular concern in light of the high proportion of NPI in our older HIV+sample, as older adults with HIV with cognitive impairment may be at increased risk for poor medication adherence.59 Collectively, this highlights the importance of effective HIV disease management, particularly in older HIV+individuals, who may be especially susceptible to these co-morbid medical conditions that may further exacerbate HIV disease.

In the younger HIV+group, current neuropsychiatric distress (i.e., POMS Total Mood Disturbance) was the only significant correlate of medical co-morbidity burden, which was primarily driven by the depression/dejection and vigor/activation subscales. Although these data are observational and correlational, it is possible that there is a bidirectional relationship between these affective symptoms and medical co-morbidity burden. Specifically, greater medical co-morbidity burden may lead to more negative affective symptoms (e.g., depression, lethargy), or vice versa (e.g., leading a sedentary lifestyle may cause the development of medical co-morbidities). Interestingly, despite similar levels of self-reported affective distress and proportions of MDD, this association was not observed in the older HIV+cohort. One explanation is that the etiology of mood symptoms may differ for younger and older HIV+ groups, and that medical co-morbidity burden is not a major cause of depression in older HIV+ adults when other potential causes are considered (e.g., loss of a partner, reduced independence). Nonetheless, it is important to highlight the role of affective distress in medical co-morbidity burden as mood symptoms (e.g., depression, apathy) have been associated with adverse functional outcomes in HIV, including medication nonadherence,58 difficulties with everyday activities,62 and poorer HRQoL,63 and are amenable to detection and intervention.64 Thus, effective screening and treatment of mood symptoms, as well as encouraging healthy behaviors that have been utilized in treatment (e.g., exercise65), may help to prevent the development of medical conditions that may result as a consequence of mood related issues and improve the medical health of younger HIV+individuals.

The clinical relevance of this study is highlighted by the independent association between medical co-morbidity burden and physical HRQoL across the lifespan. Specifically, a greater medical co-morbidity burden as measured by the CCI was associated with poorer physical HRQoL in HIV-infected individuals, even while accounting for variables that differed between the groups (e.g., ethnicity, sexual orientation) and other factors known to be predictive of HRQoL (e.g., lifetime MDD10,66). Moreover, a trend-level interaction between age and co-morbidity was observed for physical HRQoL, whereby older (but not younger) PLWH with greater medical co-morbidity burden reported poorer physical HRQoL. In contrast, greater medical co-morbidity burden was not associated with poorer mental HRQoL across the lifespan. As noted above, diabetes, syndromic NPI, chronic pulmonary disease, and malignancy were the most prevalent in the HIV-infected group, which suggests that these conditions may play a unique role in physical HRQoL outcomes in HIV. This is consistent with previous research demonstrating associations between poorer HRQoL and neurocognitive impairment (e.g., prospective memory66). Relatedly, diabetes and chronic lung disease have been associated with clinician-rated functional outcomes10 and reduced ability to carry out physical day-to-day activities (e.g., eating, walking, running26), respectively. Collectively, these results suggest that adverse functional and health-related outcomes may be associated with co-morbid medical conditions that are highly prevalent in HIV infection, particularly in older adults.

The current study has a few limitations that are worth consideration. First, the cross-sectional nature of our study does not allow for conclusions regarding causality; for example, we are unable to determine whether the increased rates of age-related medical co-morbidities is a cause of accelerated aging due to HIV. We also made a few modifications to the comprehensive medical co-morbidity index that limits comparison of our results with other studies. As mentioned above, CCI coding of “dementia” was adjusted to a classification that corresponds roughly to a diagnosis of mild neurocognitive disorder (MND) in HIV infection40 to account for the recent decrease in the prevalence rates of HIV-associated dementia (HAD)38 and increase in the rates of milder forms of cognitive impairment in HIV infection,39 as well as the demonstrated impact of neurocognitive impairment on mortality in HIV.67,68 Moreover, we excluded AIDS diagnoses from the CCI given the nature of our clinical samples (i.e., HIV-infected versus HIV-seronegative individuals), and due to the arguably outdated index score for the AIDS diagnosis.36 However, future research using a CCI including AIDS with an updated index score may provide additional useful information with regard to the influence of disease progression on medical co-morbidity burden in both younger and older HIV-infected adults.

With regard to the demographic characteristics of the study samples, our HIV+group were predominantly male, which limits the generalizability of our findings, given evidence to suggest lower HRQoL in women with HIV.69–71 Our “older” samples were also relatively young relative to the mean age in traditional aging literature, and the prevalence and clinical correlates of medical co-morbidity and HRQoL may differ as these older HIV infected individuals reach later decades (e.g., 70s and 80s). Moreover, our older HIV+cohorts were mostly Caucasian, which is likely reflective of larger cohort effects evident in the San Diego County HIV epidemic.72 While we did not find an association between ethnicity and either physical or mental HRQoL in the current analyses, future research should continue to consider ethnicity as a potential contributing factor, given prior evidence of poorer self-reported HRQoL in ethnic minorities (e.g., Hispanic individuals) with HIV infection73 and the importance of HRQoL in HIV-related health outcomes and treatment. Lastly, due to the cognitive focus of parent study from which these data were drawn, we excluded individuals with very low reading abilities (i.e., estimated premorbid verbal intelligence less than 70), which inherently limits the generalizability of our findings, particularly given the potential role of health literacy in co-morbidity burden and its impact on HRQoL.74

Also of note is that the vast majority of our sample was on antiretroviral medications, some of which have been associated with higher risk for cardiovascular and metabolic complications.75 Relatedly, we did not thoroughly examine the effects of specific non-HIV medications in older HIV-infected adults. While there was an association between total number of non-HIV medications and medical co-morbidity burden, we were unable to determine whether specific medications were driving these effects. Further research is needed to identify specific HIV and non-HIV related medications that may be associated with greater medical co-morbidity burden so that medication regimens may be appropriately and individually adjusted based on the risk of various medical conditions.

Despite these limitations, these findings are of significant clinical and public health interest. Advances in treatment have led to significant decreases in AIDS-related events, though non-AIDS related conditions (e.g., cardiovascular complications, malignancies) have increased,56,76 particularly in older HIV-infected individuals. Co-morbid medical conditions can result from a myriad of factors including HIV-disease and age-associated factors, as well as HIV treatment characteristics (e.g., antiretroviral therapy), which should be taken into consideration when reviewing treatment options and developing appropriate medication regimens. Moreover, many of these conditions are amenable to treatment to some degree, thus it is critical that HIV-infected individuals, particularly those who are older, receive comprehensive medical evaluations to ensure early detection and remediation of conditions or symptoms in order to reduce co-morbid medical burden and improve overall health-related quality of life.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: The HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) Group

Acknowledgments

The San Diego HIV Neurobehavioral Research Program (HNRP) group is affiliated with the University of California, San Diego, the Naval Hospital, San Diego, and the Veterans Affairs San Diego Healthcare System, and includes: Director: Igor Grant, MD; Co-Directors: J. Hampton Atkinson, MD, Ronald J. Ellis, MD, PhD, and J. Allen McCutchan, MD; Center Manager: Thomas D. Marcotte, PhD; Jennifer Marquie-Beck, MPH; Melanie Sherman; Neuromedical Component: Ronald J. Ellis, MD, PhD (P.I.), J. Allen McCutchan, MD, Scott Letendre, MD, Edmund Capparelli, PharmD, Rachel Schrier, PhD, Terry Alexander, RN, Debra Rosario, MPH, Shannon LeBlanc; Neurobehavioral Component: Robert K. Heaton, PhD (P.I.), Steven Paul Woods, PsyD, MarianaCherner, PhD, David J. Moore, PhD, Matthew Dawson; Neuroimaging Component: Terry Jernigan, PhD (P.I.), Christine Fennema-Notestine, PhD, Sarah L. Archibald, MA, John Hesselink, MD, Jacopo Annese, PhD, Michael J. Taylor, PhD; Neurobiology Component: Eliezer Masliah, MD (P.I.), Cristian Achim, MD, PhD, Ian Everall, FRCPsych, FRCPath, PhD (Consultant); Neurovirology Component: Douglas Richman, MD, (P.I.), David M. Smith, MD; International Component: J. Allen McCutchan, MD, (P.I.); Developmental Component: Cristian Achim, MD, PhD; (P.I.), Stuart Lipton, MD, PhD; Participant Accrual and Retention Unit: J. Hampton Atkinson, MD (P.I.); Data Management Unit: Anthony C. Gamst, PhD (P.I.), Clint Cushman (Data Systems Manager); Statistics Unit: Ian Abramson, PhD (P.I.), Florin Vaida, PhD, Reena Deutsch, PhD, Anya Umlauf, MS. The authors thank Marizela Cameron, Erica Weber, and Nichole Duarte for their assistance with study management. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01-MH73419 and T32-DA31098 to Dr. Woods, P30-MH62512 to Dr. Grant, T35-AG026757 to Dr. Dilip Jeste, and L30-DA034362 to Dr. Iudicello.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the United States Government.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2011. HIV Surveillance Report, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes AK. HIV knowledge and attitudes among providers in aging: Results from a national survey. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:539–545. doi: 10.1089/apc.2011.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC 2009; HIV Surveillance Report, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanco JR. Caro AM. Pérez-Cachafeiro S, et al. HIV infection and aging. AIDS Rev. 2010;12:218–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valcour V. Shikuma C. Shiramizu B, et al. Higher frequency of dementia in older HIV-1 individuals: The Hawaii Aging with HIV-1 Cohort. Neurology. 2004;63:822–827. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000134665.58343.8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips AN. Lee CA. Elford J, et al. More rapid progression to AIDS in older HIV-infected people: The role of CD4+ T-cell counts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:970–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Egger M. Chene G. Phillips AN, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1 infected patient starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: A collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bamford LM. Ehrenkranz PD. Eberhart MG, et al. Factors associated with delayed entry into primary HIV medical care after HIV diagnosis. AIDS. 2010;24:928–930. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337b116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner ID. The effect of aging on susceptibility to infection. Rev Infect Dis. 1980;2:801–810. doi: 10.1093/clinids/2.5.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan EE. Iudicello JE. Weber E, et al. Synergistic effects of HIV infection and older age on daily functioning. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61:341–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826bfc53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.High KP. Brennan-Ing M. Clifford DB, et al. HIV and aging: State of knowledge and areas of critical need for research. A report to the NIH Office of AIDS Research by the HIV and Aging Working Group. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:S1–S18. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31825a3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hernandez MD. Sherman KE. HIV/hepatitis C coinfection natural history and disease progression. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2011;6:478–482. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834bd365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCutchan JA. Marquie-Beck JA. Fitzsimmons CA, et al. Role of obesity, metabolic variables, and diabetes in HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2012;14:485–492. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182478d64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinkin CH. Castellon SA. Levine AJ, et al. Neurocognition in individuals co-infected with HIV and hepatitis C. J Addictive Dis. 2008;27:11–17. doi: 10.1300/j069v27n02_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilbourne AM. Justice AC. Rabeneck L, et al. General medical and psychiatric co-morbidity among HIV-infected veterans in the post-HAART era. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:S22–28. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00443-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alencastro PR. Fuchs SC. Wolff FH, et al. Independent predictors of metabolic syndrome in HIV-infected patients. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:627–634. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Backus LI. Boothroyd D. Philips B, et al. Assessment of the quality of diabetes care for HIV-infected patients in a national health care system. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:203–206. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vance D. Larsen KI. Eagerton G, et al. Co-morbidities and cognitive functioning: Implications for nursing research and practice. J Neurosci Nurs. 2011;43:215–224. doi: 10.1097/JNN.0b013e3182212a04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deeks SG. Phillips AN. HIV infection, antiretroviral treatment, ageing, and non-AIDS related morbidity. BMJ. 2009;338:288–292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guaraldi G. Orlando G. Zona S, et al. Premature age-related co-morbidities among HIV-infected persons compared with the general population. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1120–1126. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oursler KK. Goulet JL. Crystal S, et al. Association of age and co-morbidity with physical function in HIV-infected and uninfected patients: Results from the Veterans Aging Cohort Study. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2011;25:13–20. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goulet JL. Fultz SL. Rimland D, et al. Do patterns of co-morbidity vary by HIV status, age, and HIV severity? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:1593–1601. doi: 10.1086/523577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasse B. Ledergerber B. Furrer H, et al. Morbidity and aging in HIV-infected persons: The Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:1130–1139. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss JJ. Osorio G. Ryan E, et al. Prevalence and patient awareness of medical co-morbidities in an urban AIDS clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010;24:39–48. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters L. Neuhaus J. Mocroft A, et al. Hyaluronic acid levels predict increased risk of non-AIDS death in hepatitis co-infected persons interrupting antiretroviral therapy in the SMART study. Antivir Ther. 2011;16:667–675. doi: 10.3851/IMP1815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oursler KK. Goulet JL. Leaf DA, et al. Association of co-morbidity with physical disability in older HIV-infected adults. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20:782–791. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woods SP. Dawson MS. Weber E, et al. The semantic relatedness of cue-intention pairings influences event-based prospective memory failures in older adults with HIV infection. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2010;32:398–407. doi: 10.1080/13803390903130737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, version 2.1) Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hall SF. A user's guide to selecting a co-morbidity index for clinical research. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;59:849–855. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Skiest DJ. Rubinstien E. Carley N, et al. The importance of co-morbidity in HIV-infected patients over 55: A retrospective case-control study. Am J Med. 1996;101:605–611. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00329-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lohse N. Gerstoft J. Kronborg G, et al. Co-morbidity acquired before HIV diagnosis and mortality in persons infected and uninfected with HIV: A Danish population-based cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57:334–339. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31821d34ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tumbarello M. Rabagliati R. de Gaetano Donati K, et al. Older age does not influence CD4 cell recovery in HIV-1 infected patients receiving highly active anti retroviral yherapy. BMC Infect Dis. 2004;4:46. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-4-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Charlson ME. Pompei P. Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic co-morbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zavascki AP. Fuchs SC. The need for reappraisal of AIDS score weight of Charlson co-morbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:867–868. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deyo RA. Cherkin DC. Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical co-morbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heaton RK. Clifford DB. Franklin DR, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders persist in the era of potent antiretroviral therapy. Neurology. 2010;75:2087–2096. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318200d727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heaton RK. Franklin DR. Ellis EJ, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: Differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antinori A. Arendt G. Becker JT, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69:1789–1799. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods SP. Morgan EE. Dawson M, et al. Action (verb) fluency predicts dependence in instrumental activities of daily living in persons infected with HIV-1. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2006;28:1030–1042. doi: 10.1080/13803390500350985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Woods SP. Rippeth JD. Frol AB, et al. Interrater reliability of clinical ratings and neurocognitive diagnoses in HIV. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2004;26:759–778. doi: 10.1080/13803390490509565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawton MP. Brody EM. Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9:179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heaton RK. Marcotte TD. Rivera-Mindt M, et al. The impact of HIV-associated neuropsychological impairment on everyday functioning. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2004;10:317–331. doi: 10.1017/S1355617704102130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Woods SP. Iudicello JE. Moran LM, et al. HIV-associated prospective memory impairment increases risk of dependence in everyday functioning. Neuropsychology. 2008;22:110–117. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.22.1.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McNair DM. Lorr M. Droppleman LF. Profile of Mood States. San Diego, CA: Educational and Industrial Testing Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bing EG. Hays RD. Jacobson LP, et al. Health-related quality of life among people with HIV disease: Results from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Qual Life Res. 2000;9:55–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1008919227665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamping DL. Methods for measuring outcomes to evaluate interventions to improve health-related quality of life in HIV infection. Psychol Health. 1994;9:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jia H. Uphold CR. Wu S, et al. Health-related quality of life among men with HIV infection: Effects of social support, coping, and depression. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2004;18:594–603. doi: 10.1089/apc.2004.18.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nokes KM. Symptom disclosure by older HIV-infected persons. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2011;22:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grinspoon S. Carr A. Cardiovascular risk and body-fat abnormalities in HIV-infected adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:48–62. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Isomaa B. Almgren P. Tuomi T, et al. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality associated with the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:683–689. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.4.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Monroe AK. Chander G. Moore RD. Control of medical co-morbidities in individuals with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58:458–452. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31823801c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grabar S. Kousignian I. Sobel A, et al. Immunological and clinical responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy over 50 years of age. Results from the French Hospital Database on HIV. AIDS. 2004;18:2029–2038. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200410210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reekie J. Kosa C, Engsig F, et al. Relationship between current level of immunodeficiency and nonacquired immunodeficiency syndromes-defining malignancies. Cancer. 2010;116:5306–5315. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palella FJ., Jr Baker RK. Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: Changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Iudicello JE. Woods SP. Deutsch R. Grant I The HNRP Group. Combined effects of aging and HIV infection on semantic verbal fluency: A view of the cortical hypothesis through the lens of clustering and switching. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34:476–488. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.651103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barclay TR. Hinkin CH. Castellon SA, et al. Age-associated predictors of medication adherence in HIV-positive adults: health beliefs, self-efficacy, and neurocognitive status. Health Psychol. 2007;26:40–49. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thames AD. Kim MS. Becker BW, et al. Medication and finance management among HIV-infected adults: The impact of age and cognition. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2011;33:200–209. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.499357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schuster RM. Gonzalez R. Substance abuse, hepatitis C, and aging in HIV: Common cofactors that contribute to neurobehavioral disturbances. Neurobehav HIV Med. 2012;4:15–34. doi: 10.2147/NBHIV.S17408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grunfeld C. Delaney JA. Wanke C, et al. Preclinical atherosclerosis due to HIV infection: Carotid intima-medial thickness measurements from the FRAM study. AIDS. 2009;23:1841–1849. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832d3b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kamat R. Woods SP. Marcotte TD, et al. Implications of apathy for everyday functioning outcomes in persons living with HIV infection. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2012;27:520–531. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acs055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tate D. Paul RH. Flanigan TP, et al. The impact of apathy and depression on quality of life in patients infected with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2003;17:115–120. doi: 10.1089/108729103763807936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zisook S. Peterkin J. Goggin KJ, et al. Treatment of major depression in HIV-seropositive men. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:217–224. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v59n0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neidig JL. Smith BA. Brashers DE. Aerobic exercise training for depressive symptom management in adults living with HIV infection. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2003;14:30–40. doi: 10.1177/1055329002250992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doyle K. Weber E. Atkinson JH. Grant I. Woods SP The HNRP Group. Aging, prospective memory, and health-related quality of life in HIV infection. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:2309–2318. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0121-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ellis RJ. Deutsch R. Heaton RK, et al. Neurocognitive impairment is an independent risk factor for death in HIV infection. Arch Neurol. 1997;54:416–424. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550160054016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tozzi V. Balestra P. Serraino D, et al. Neurocognitive impairment and survival in a cohort of HIV-infected patients treated with HAART. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2005;21:706–713. doi: 10.1089/aid.2005.21.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cederfjäll C. Languis-Eklöf A. Lidman K. Wredling R. Gender difference in perceived health-related quality of life among patients with HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2001;15:31–39. doi: 10.1089/108729101460083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.O'Keefe EA. Wood R. The impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) on quality of life in a multiracial South African population. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:275–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00434749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Holzemer WL. Gygax Spicer J. Skodol Wilson H. Kemppainen JK. Coleman C. Validation of the quality of life scale: Living with HIV. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28:622–630. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Health and Human Services Agency. HIV/AIDS Epidemiology Report, 2012. San Diego: County of San Diego Health and Human Services Agency (HHSA); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Campsmith ML. Nakashima AK. Davidson AJ. Self-reported health-related quality of life in persons with HIV infection: Results from a multi-site interview project. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:12. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sørensen K. Van den Broucke S. Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: A systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health. 2012;25:12–80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Friis-Møller N. Sabin CA. Weber R, et al. Combination antiretroviral therapy and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1993–2003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mocroft A. Reiss P. Gasiorowski J, et al. Serious fatal and nonfatal non-AIDS-defining illnesses in Europe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55:262–270. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181e9be6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]