Abstract

Aim

To report the retinal signs that distinguish abusive head trauma (AHT) from non-abusive head trauma (nAHT).

Methods

A systematic review of literature, 1950–2009, was conducted with standardised critical appraisal. Inclusion criteria were a strict confirmation of the aetiology, children aged <11 years and details of an examination conducted by an ophthalmologist. Post mortem data, organic disease of eye, and inadequate examinations were excluded. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine odds ratios (OR) and probabilities for AHT.

Results

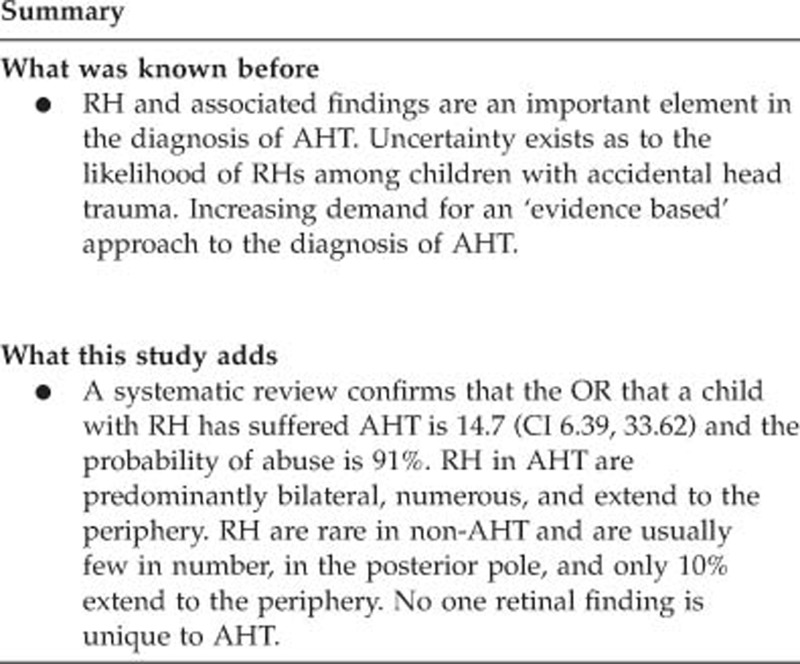

Of the 62 included studies, 13 provided prevalence data (998 children, 504 AHT). Overall, retinal haemorrhages (RH) were found in 78% of AHT vs 5% of nAHT. In a child with head trauma and RH, the OR that this is AHT is 14.7 (95% confidence intervals 6.39, 33.62) and the probability of abuse is 91%. Where recorded, RH were bilateral in 83% of AHT compared with 8.3% in nAHT. RH were numerous in AHT, and few in nAHT located in the posterior pole, with only 10% extending to periphery. True prevalence of additional features, for example, retinal folds, could not be determined.

Conclusions

Our systematic review confirms that although certain patterns of RH were far commoner in AHT, namely large numbers of RH in both the eyes, present in all layers of the retina, and extension into the periphery, there was no retinal sign that was unique to abusive injury. RH are rare in accidental trauma and, when present, are predominantly unilateral, few in number and in the posterior pole.

Keywords: child abuse, abusive head trauma, retinal haemorrhages, accidental trauma, meta-analysis

Introduction

The correct diagnosis of abusive head trauma (AHT) in children is both challenging and crucially important. AHT remains the commonest cause of fatal abuse in young children, and retinal haemorrhages (RH) are recognised as a key feature of this condition.1, 2 It has previously been proposed that retinal folds and haemorrhagic retinoschisis in an infant with brain injury may be diagnostic of a shaking injury.1, 3, 4 Recently, however, extensive RH, retinal folds, and schisis cavities have been reported in witnessed accidental head injuries,5, 6, 7 calling into question the validity of ‘classic' descriptions of retinal findings in AHT.

The ophthalmological opinion is pivotal in these cases and, given the increasing expectations of clinicians to offer a ‘scientific basis' for any estimate of probability of abuse in a child with RH, we have conducted a systematic review to address the question ‘What pattern of RH and associated retinal features distinguish between AHT and non-abusive head trauma (nAHT)?'

Materials and methods

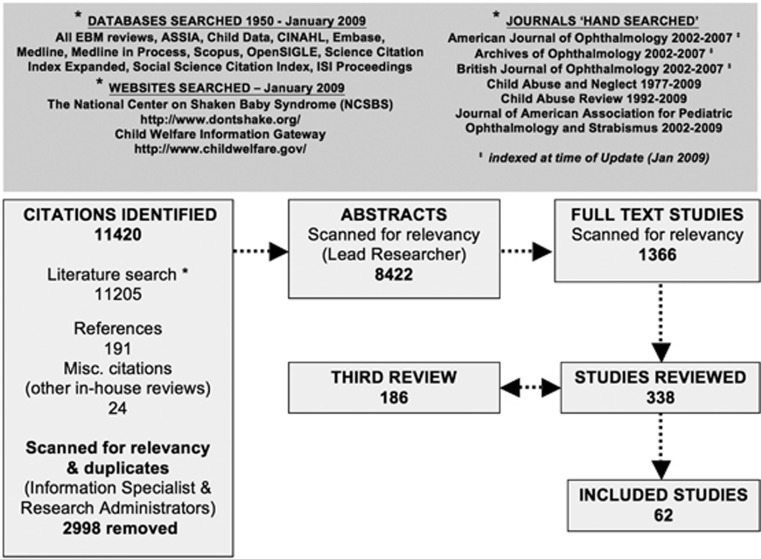

Our systematic review included an all-language literature search across 12 bibliographic databases, supplemented by a hand search of selected websites and non-indexed journals, and the references of all full-text articles, to identify original articles published from 1950 to January 2009 (Figure 1). We combined three sets of keywords, one relating to all terms encompassing child abuse (eg, shaken baby syndrome, battered baby), one relating to child terms (neonate, baby and so on), and 75 words or phrases relating to specific retinal findings or relevant coexistent conditions (eg, RH, subhyaloid haemorrhage, and so on) (Supplementary Appendix 1). Identified articles were transferred to a database to coordinate the review and collate critical appraisal data. Relevant studies with an english language version available were reviewed. Authors were contacted for the primary data and additional information where necessary.

Figure 1.

Systematic review search strategy and review process.

Quality standards

A key standard for included studies was confirmation of an abusive aetiology in AHT. Thus, we have adopted our previously published2 ‘rank of abuse' where ranks 1 or 2 minimise ‘circularity' in diagnosis, by not relying solely on clinical features (Table 1). Thus, any studies that relied solely on the physical findings alone to determine abusive injury, without a full multidisciplinary assessment, or those where abuse was simply ‘suspected', were excluded. This avoids the risk that the diagnosis of abuse may have been made solely on the basis of the injuries under analysis. An abusive aetiology was only accepted where there had been an admission, witnessed abuse or at the least a full multidisciplinary assessment. The comparative cases (nAHT) for this review were exclusively confirmed accidental trauma, that is, where the study had explicit criteria for determination of accidental origins/described the mechanism of injury. The second quality standard relates to the ophthalmological examination. Our highest rank was an examination conducted by an ophthalmologist, using indirect ophthalmoscopy and pupillary dilatation (+/− additional retinal imaging), with detailed recording of the retinal findings relating to RH (laterality, layers of retina involved, number and extent (from optic disc to peripheral retina) of haemorrhages) and additional features (eg, retinoschisis). Our minimum accepted standard was an examination by an ophthalmologist, as it is well-recognised that non-ophthalmologists may miss RH8 and additional findings are unlikely to have been documented in detail. We also wished to determine any correlation between specific intracranial findings and retinal findings.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Studies of children aged 0 to <11 years | |

| AHT—ranking of abuse of 1–2 | |

| nAHT—non-abusive aetiology confirmed (abuse excluded/accident confirmed) | |

| Ophthalmic examination performed by an ophthalmologist | |

| Ophthalmic findings described with reference to severity, location, and laterality | |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Consensus statements or personal practice studies | |

| Study exclusively addresses retinal findings in association with: | |

| Prior ophthalmic surgery | |

| Solid mass lesions of the eye (eg, retinoblastoma) or brain | |

| Post mortem examination alone (ie, where eyes not examined in life) | |

| Medical causes of RH | |

| RH found in the immediate postnatal period | |

| Blunt trauma to the eye | |

| AHT—ranking of abuse within study of 3–5 or mixed ranking where cases ranked 1–2 could not be extracted | |

| Ophthalmic examination performed by non-ophthalmologist | |

| Ranking | Criteria used to define abuse |

| 1 | Abuse confirmed at case conference or admitted by perpetrator, or independently witnessed (with or without subsequent legal proceedings) |

| 2 | Abuse confirmed by stated criteria including multidisciplinary assessment (social services/law enforcement/medical) |

| 3 | Abuse defined by stated criteria |

| 4 | Abuse stated but no supporting detail given |

| 5 | Suspected abuse |

Statistical analysis: probability of AHT when RH present/absent

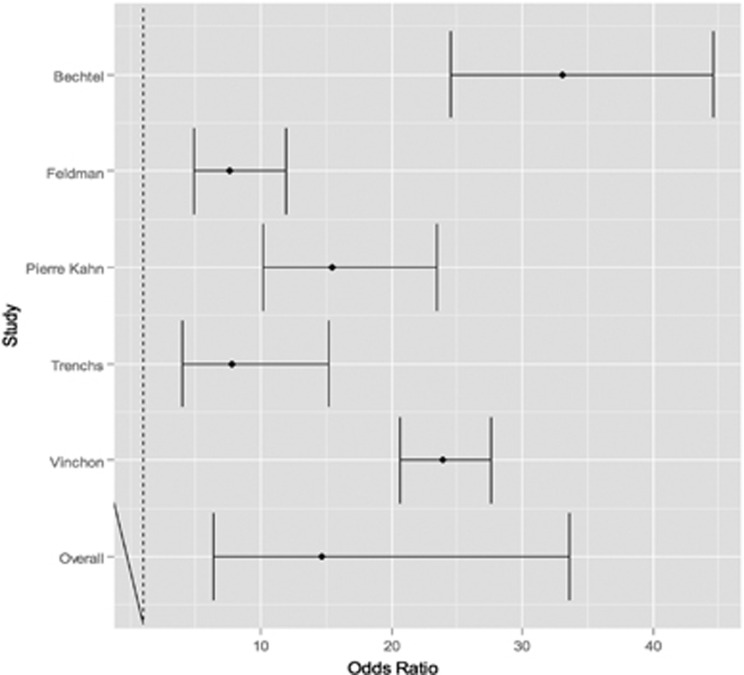

A multilevel logistic regression analysis was carried out using R (version 2.10.1, The Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/2.10.1/) on five comparative studies suitable for analysis. R is a widely used cross platform programming language and software environment for statistical computing, and graphics and data analysis.9

This multilevel approach allows for the possibility that data may be more strongly correlated within the studies than between the studies.10 The estimated odds ratios (ORs are shown for the overall analysis, as well as for the individual studies, along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Results

Of the 338 studies reviewed, 62 met the inclusion criteria. 8 studies were comparative, including three cross-sectional,11, 12, 13 two comparative case series,14, 15 one prospective cohort study,16 one case–control17 and one retrospective cohort study.18 The remainder were case reports5, 6, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 or case series,3, 7, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 concerning AHT alone,3, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 49, 50, 51, 53, 54, 55, 56, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 65, 68 and nAHT alone,5, 6, 24, 32, 44, 46, 47, 48, 52, 57, 64, 66, 67 and one with both.7 Where details were lacking, the authors provided further information relating to ophthalmological examination details, findings, and confirmation of aetiology by personal correspondence.32 Although Haviland et al17 was a case–control study, only AHT cases had ophthalmological examinations, and thus were analysed with the non-comparative data. One study group (Vinchon et al) provided us with access to their raw data set, incorporating data used in the three studies,13, 16, 67 including two comparative studies13, 16 and one non-comparative study regarding motor vehicle collisions.67 The data set for each of these three studies was ascertained simultaneously utilising the same criteria and we have, therefore, interpreted the data as one continuous set for the purposes of our analysis.

The commonest reasons for exclusion of studies were inadequate confirmation of abuse or an inadequate standard of ophthalmological examination recorded in the study. Data were interpreted in three data sets:

Data set 1: Larger studies with consecutive cases presented—suitable for prevalence analysis and homogenous comparative studies entered into a meta-analysis.11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 18, 47, 56, 61, 64, 66 (Vinchon raw data set) 13, 16, 67

Data set 2: Highly selected case series/studies with <10 subjects each.3, 5, 6, 7, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 57, 58, 59, 60, 62, 63, 65, 68

Data set 3: Both of the above data sets combined.

The total data set 3 includes 998 children, 504 with AHT. All AHT cases in the comparative studies were <3 years (mean age could not be determined), however, the non-comparative studies recorded five older abused children,31, 51(Case 5),63(Cases 1,2,4) (Supplementary Appendix 2), all of whom were severely injured, four fatally. Among nAHT cases, 11/13 of the large studies addressed children <3 years, and the oldest child with RH in the remaining studies was 10 years52 (aetiology of nAHT—Supplementary Appendix 3).

The multilevel logistic regression analysis (Table 2 and Figure 2) details the probability of abuse when a child with head trauma is found to have RH, with an OR of 14.66 and an estimated probability of 91% (95% CIs 48%, 99%).

Table 2. Studies included in multilevel logistic regression analysis.

| Study ID | Year | RH present/total AHT cases | RH present/total nAHT cases | OR (with 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bechtel et al11 | 2004 | 9/15 | 7/67 | 33.07 (24.55, 44.57) |

| Feldman et al14 | 2001 | 28/39 | 1/3 | 7.64 (4.89, 11.93) |

| Pierre-Kahn et al15 | 2003 | 13/16 | 0/7 | 15.44 (10.15, 23.51) |

| Trenchs et al18 | 2007 | 6/10 | 1/1 | 7.81 (4.02, 15.20) |

| Vinchon et al13,a | 2005 | 72/95 | 13/141 | 23.88 (20.63, 27.64) |

| Overall | 128/175 | 22/219 | 14.66 (6.39, 33.62) |

Abbreviations: AHT, abusive head trauma; CI, confidence interval; nAHT, non-abusive head trauma; OR, odds ratio; RH, retinal haemorrhage.

Indicates data drawn from all three studies.

Figure 2.

Odds of AHT in a child with RH: multilevel logistic regression analysis.

Retinal findings

The features of the RH in relation to laterality, number and extent of haemorrhages and the layers of retina involved, are summarised for data set 1 (Table 3). Of the 363 children with AHT, 78% (283) had RH vs 5% (25/465) of children with nAHT. Six studies recorded the laterality of RH in AHT11, 12, 17, 18, 56, 61 and four in nAHT.11, 14, 18, 66 Of these, 83% (141/170) of AHT cases had bilateral RH vs 8% (1/12) case of nAHT,11 this latter case was an 8-month old who had 10 RH per eye following a fall from a bed onto a linoleum floor.

Table 3. Layer of retina involved in cases of AHT and nAHT (data set 1), where sufficient detail given.

|

No. of intraretinal haemorrhage/total cases with RH |

No. of preretinal haemorrhage/total cases with RH |

No. of subretinal haemorrhage/total cases with RH |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | AHT | nAHT | AHT | nAHT | AHT | nAHT |

| Bechtel et al11 | 9/9 | 7/7 | 5/9 | 0/7 | N/A | N/A |

| Buys et al12 | 3/3 | No RH | 2/3 | No RH | N/A | No RH |

| Elder et al47 | N/A | No RH | N/A | No RH | N/A | No RH |

| Feldman et al14 | 28/28 | 1/1 | 0/28 | 1/1 | N/A | N/A |

| Haviland and Ross Russell17 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Kivlin et al56 | 76/76 | N/A | 36/76 | N/A | 10/76 | N/A |

| Morad et al61 | 58/64 | N/A | 58/64 | N/A | 47/64 | N/A |

| Pierre-Kahn et al15 | 13/13 | No RH | N/A | No RH | N/A | No RH |

| Trenchs et al18 | 2/6 | 1/1 | 4/6 | N/A | 1/6 | N/A |

| Trenchs et al66 | N/A | 2/3 | N/A | 1/3 | N/A | N/A |

| Vinchon et ala,13, 16, 67 | 72/72 | 13/13 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 261/271 (96%) | 24/25 (96%) | 105/186 (56%) | 2/11 (18%) | 58/146 (40%) | — |

Abbreviations: AHT, abusive head trauma; nAHT, non-abusive head trauma; N/A, not assessed/not mentioned; RH, retinal haemorrhage.

Indicates data drawn from all three studies.

Four studies mentioned the number of RH in AHT11, 12, 18, 61 and three in nAHT.11, 14, 66 As terminology varied, we took the following terms to indicate ‘larger' numbers of RH present: multiple, diffuse, extensive, numerous, ‘too numerous to count', marked, massive, extended, scattered, many, and severe. Terms taken to represent ‘smaller' numbers were: ‘single haemorrhage', few and small. The majority of AHT cases, 83%, (60/72) had larger numbers of RH, while none of the eight cases of nAHT with this information had extensive RH.

The distribution of RH (eg, did they extend to the periphery), was only recorded in seven AHT11, 18, 56, 61 (Vinchon raw data set)13, 16, 67 and seven nAHT11, 14, 18, 66 (Vinchon raw data set)13, 16, 67 studies. The majority of AHT cases, 63%, (101/160) had peripheral extension of RH, while only 9% (2/22) of nAHT cases had.(Vinchon raw data set)13, 16, 67 The recording of the layer (intraretinal, preretinal, or subretinal haemorrhage) in which the RH was present is varied across the 13 studies and no consistent terminology was used (Table 3). Only three studies report the prevalence of RH in multiple layers for AHT cases.18, 56, 61 Pooled data from these three studies reported RH in 81% (146/180)18, 56, 61 of infants with AHT with 84% (122/146) being bilateral. Prevalence of multilayered RH which could be extracted from two studies18, 61 was 77% (54/70). RH in all the three layers were described in a single study, recorded as present in 73% (47/64) of infants.61

Retinal findings: additional features (data set 3)

There were a wide range of additional retinal features described for both AHT and nAHT cases (Table 4). The true prevalence of traumatic retinoschisis or retinal folds in AHT could not be determined as only one study56 in data set 1 described perimacular retinal folds (7/76 AHT cases) and none recorded the presence or absence of retinoschisis. Among the case reports, three cases of accidental (nAHT) retinoschisis were noted following an 11 m fall32 and two crush injuries to the head, one by an adult7 and the second by a 63-kg child.6 Perimacular retinal folds were also found in two of these cases6, 7 and in a third child who was crushed by a 19.5 kg television.5 Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) was mentioned in two cases of AHT, one of which noted bilateral PVDs22 but unilateral RH, with vitreous detachment in the presence of a large preretinal haemorrhage in the other eye.43 Of note, no cases of nAHT recorded retinal tears, epiretinal membrane, macular hole, neovascularisation, vitreous detachment, and choroidal rupture; however, exudates were found in nAHT cases, but not in AHT cases (Table 4 and Supplementary Figure 1).

Table 4. Detailed retinal findings (data set 3).

| Retinal features (where present) | AHT (423/504 cases with retinal findings/total) | References | nAHT (44/494 cases with retinal findings/total) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraretinal haemorrhages | 390 | 3, 7, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 23, 25, 26, 27, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 49, 50, 51, 53, 55, 56, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 65 | 39 | 5, 6, 7, 11, 14, 18, 24, 32, 44, 46, 48, 52, 57, 64, 66(Vinchon raw data set)13, 16, 67 |

| Preretinal haemorrhages | 178 | 3, 19, 25, 26, 27, 29, 33, 38, 40, 43, 45, 49, 51, 53, 56, 59, 60, 61, 65 | 10 | 5, 14, 24, 32, 44, 48, 52, 66 |

| Subretinal haemorrhages | 69 | 3, 18, 21, 27, 31, 40, 42, 49, 50, 56, 61, 62, 65 | 1 | 32 |

| Vitreous haemorrhages | 41 | 3, 11, 12, 22, 28, 29, 31, 36, 39, 42, 43, 45, 49, 50, 56, 58, 59, 60 | 2 | 6, 46 |

| Schisis cavities (peripheral retinoschisis, retinoschisis, macular schisis) | 30 | 7, 38, 60, 61, 63 | 3 | 6, 7, 32 |

| Retinal folds | 21 | 7, 38, 39, 42, 45, 49, 53, 56, 60, 65 | 3 | 5, 6, 7 |

| Dome like RH under ILM | 7 | 56 | 0 | |

| Exudates | 0 | 4 | 57 | |

| Dot/blot RH | 12 | 11, 12, 25, 45, 55 | 4 | 5, 24, 46, 64 |

| Flame RH or NFL RH | 11 | 11, 12, 25, 29, 55, 65 | 3 | 24, 46, 64 |

| White centred RH | 15 | 7, 11, 18, 43, 45, 55 | 2 | 24, 48 |

| Disc swelling/papilledema | 10 | 49, 50, 56, 61 | 1 | 57 |

| Optic nerve haemorrhage | 10 | 22, 33, 49, 60, 62 | 0 | |

| Retinal detachment | 8 | 12, 27, 28, 30, 37, 42, 54, 62 | 0 | |

| Retinal tears/peripheral retinal holes | 6 | 28, 30, 37, 58a | 0 | |

| Epiretinal membrane | 1 | 23 | 0 | |

| Macular hole | 2 | 20, 58b | 0 | |

| Retinal neovascularisation | 3 | 42, 65 | 0 | |

| Choroidal rupture | 1 | 56 | 0 | |

| Retinal oedema | 1 | 49 | 3 | 44, 46, 57 |

| Vitreous detachment | 2 | 22, 43 |

Abbreviations: HT, abusive head trauma; ILM, inner limiting membrane; nAHT, non-abusive head trauma; NFL, nerve fibre layer; RH, retinal haemorrhage.

Found during vitrectomy.

Macular hole found at vitrectomy.

Coexistent intracranial features in children with RH

Few studies recorded detailed associated findings, precluding analysis. Among the comparative studies (131 AHT, 22 nAHT) with details of neuro-imaging,11, 12, 14, 15, 18 (Vinchon raw data set)13, 16, 67 all cases (AHT and nAHT) with RH showed intracranial abnormalities (one nAHT case with a depressed skull fracture alone13). These included any combination of extra-axial haemorrhage, cerebral contusion, intra-cerebral abnormality, and cerebral oedema. Coexistent extradural haemorrhages (EDH) and RH were noted in five cases of nAHT, although the RH was only noted following drainage of the EDH.48

Of note, among the non-comparative studies (data set 2) there are nine cases (aged 2–24 months) of AHT with RH, presenting with neurological symptoms, but no neuro-radiological abnormalities on presentation25, 35, 50, 69 (six from a single study69 are same cases as Morad et al,61 confirmed by authors). While 6/9 had computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), three had CT only.35, 50, 69(Case 4) However, repeated CT showed a focal area of encephalomalacia 1 month later in one case35 and bilateral subdural haemorrhages (SDH) 2 weeks later in a second.50 In a third case, 7 days after an initial negative CT and MRI, repeated MRI showed SDH.69(Case 7) No repeat CT or MRI was performed in 5/925, 69(Cases 1,5,6,8) but in one case three MRI scans (performed for 24 h, 7 days, 6 months) were normal,69(Case 3) despite presenting with seizures, lethargy, and irregular breathing.

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review, reflecting data on almost a thousand children, including a meta-analysis of five studies, has confirmed that RH have a strong association with AHT (OR 14.7, probability 91%) and are rarely present following accidental trauma. This review is unique in applying strict standards of ophthalmological examination, and security of diagnosis of abuse and non-abusive trauma, thus meeting the stringent standards that are now expected both in a clinical and legal setting.

RH were rarely described in nAHT, and those described were predominantly few in number, unilateral and located at the posterior pole, with extension into the periphery occurring infrequently. However, although certain patterns of RH were far commoner in AHT, namely large numbers of RH in both the eyes present in all layers of the retina and extension into the periphery, there was no pattern of RH that was unique to abusive injury. Although the majority of nAHT cases had unilateral RH, these were reported in 17% of AHT. Given the association between bilateral RH and AHT, it is disappointing that this level of detail is often missing in the literature. Similarly, the presence of subretinal blood seems to be extremely rare in nAHT, recorded in only one child.32 Owing to the inconsistent recording of additional retinal findings (other than RH) in the large scale studies, it was impossible to determine their true prevalence. These included features previously described as ‘pathognomonic' of AHT, namely ‘extensive RH accompanied by perimacular folds and schisis cavities found in association with intracranial haemorrhage or other evidence of trauma to the brain in an infant without another clear explanation'.1, 3, 4, 70 In particular, it is unclear if the absence of features, such as retinoschisis or perimacular retinal folds, in the nAHT literature reflects the absence of data or the absence of recording. However, these features were not recorded in any nAHT cases within the consecutive data sets, appearing only in isolated case reports.6, 7, 32

The included studies ascertained children presenting with head trauma or SDH and, while it is clear that 97% of those with RH had coexistent intracranial abnormalities, there were nine AHT cases described as having normal imaging at the outset. These cases had abnormal neurological signs, three with evidence of intracranial injury on follow-up imaging, one without and five had no follow-up MRI, which would be the optimal imaging strategy.

The mechanism of injury for those children with RH and nAHT varied from motor vehicle collision to falls. The falls concerned included only one from >20 feet, two between 4 and 20 feet and eight below four feet, thus it was not possible to define precise patterns of injury by fall height. Although crush injury is a rare cause of accidental childhood trauma, it was described in 15 children, six of whom had RH. Three of these had extensive, multilayered RH, more commonly seen in AHT.5, 6, 7 Thus, while only a fifth of the described crush injuries resulted in severe RH, it is an important mechanism to be aware of, as in common with a high fall, they may result in the ‘classical' retinal features of AHT.

Unfortunately, many studies could not be included in the review due either to inadequate multidisciplinary confirmation of abuse,71 lack of ophthalmological detail, or details of the standard of ophthalmological examination.72 Clearly an optimal examination, in particular ensuring an adequate view of the periphery, is essential, even though this may be technically challenging in an awake infant. Two studies have documented peripheral haemorrhages in the absence of posterior pole findings in AHT.18, 51 As with all systematic reviews, analysis of potential confounding factors in relation to RH, for example, severe raised intracranial pressure,15, 61 coagulopathy, and so on, was hindered by a lack of detail in the primary studies.

Unfortunately, primary authors used a wide variety of nomenclature and reported detailed findings variably, thus hampering a meta-analysis of specific retinal features. We would, therefore, strongly recommend that ophthalmologists adopt a standardised examination record of all children with suspected AHT. This should define the extent, layer (eg, preretinal, intraretinal, and subretinal) and location within the retina of any RH, and the presence/absence of any additional findings.73 This will require consensus as to precisely what they are seeing, and in which layer of the retina they determine the RH to be in.73 It is particularly important to record all relevant negative findings for example, the absence of perimacular fold, vitreous detachment, and so on, in order to determine their true sensitivity and specificity. The use of imaging techniques such as RetCam65, 74 may enhance accurate documentation, although, as a two-dimensional image, descriptions will still be needed, and it is advised that the findings from indirect examination are recorded before the use of the RetCam. The use of the RetCam may cause some discomfort, with one suggestion that it contributed to RH in a neonate.75 There have been reports of the value of optical coherence tomography (OCT)76 in defining the layer of RH and possible role of the vitreous attachments in their causation. However, the universal use of the RetCam or OCT in all cases may be limited by practicalities and cost.65

Summary

In addressing the question ‘What pattern of RH and associated retinal features distinguish between AHT and nAHT?' this rigorous systematic review, with explicit standards for confirmation/exclusion of abuse and ophthalmological examination, has confirmed RH are common in AHT, most frequently being bilateral, extensive, multilayered, and extending to the periphery. In contrast, such findings of bilateral, multilayered, confluent RH are an extremely rare finding in nAHT, where when RH are present, they are usually unilateral, posterior, and few in number. Current literature precludes a logistic regression analysis of key additional features such as schisis cavities, epiretinal membranes, or retinal folds, as their presence or absence in nAHT was not routinely recorded. These findings have a clear association with AHT, although a small number of severe crush injuries or high fall (11 m)32 have produced a similar spectrum of findings as AHT, thus no pattern of RH is ‘unique' to AHT. There is an urgent need for an international standard of examination and explicit recording of findings, including the precise site, location, extent, and level of RH, and the presence or absence of associated retinal features. This would enhance clinical practice, including second opinions, facilitate child protection reports, and contribute to future research.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to Professor Mathieu Vinchon for kindly providing access to the raw data from his three relevant studies. We are also grateful to Dr Daniel Farewell for expert statistical advice. This work is based on reviews conducted by the Cardiff Child Protection Systematic Reviews: Gillian Adams, Michelle Barber, Rachel Brooks, Howard Bunting, Nia John, Richard Jones, Amruta Joshi, Chris Lloyd, Achyut Mukherjee, Aideen Naughton, Harish Nayak, William Newman, Diane Nuttall, Gayatri Omkar, Ingrid Prosser, Alicia Rawlinson, Jonathan Sibert, David Taylor and Cathy Williams. Funding was provided by the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC), Welsh Assembly Government, Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Eye website (http://www.nature.com/eye)

Supplementary Material

References

- Levin AV. Ophthalmology of shaken baby syndrome. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2002;13:201–211. doi: 10.1016/s1042-3680(02)00004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire S, Pickerd N, Farewell D, Mann M, Tempest V, Kemp AM. Which clinical features distinguish inflicted from non-inflicted brain injury? a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2009;94:860–867. doi: 10.1136/adc.2008.150110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald MJ, Weiss A, Oesterle CS, Friendly DS. Traumatic retinoschisis in battered babies. Ophthalmology. 1986;93:618–625. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(86)33688-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massicotte SJ, Folberg R, Torczynski E, Gilliland MG, Luckenbach MW. Vitreoretinal traction and perimacular retinal folds in the eyes of deliberately traumatized children. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:1124–1127. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz PE, Sinal SH, Stanton CA, Weaver RG. Perimacular retinal folds from childhood head trauma. Br Med J. 2004;328:754–756. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7442.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lueder GT, Turner JW, Paschall R. Perimacular retinal folds simulating nonaccidental injury in an infant. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:1782–1783. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.12.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts P, Obi E. Retinal folds and retinoschisis in accidental and non-accidental head injury. Eye. 2008;22:1514–1516. doi: 10.1038/eye.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad Y, Kim YM, Mian M, Huyer D, Capra L, Levin AV. Nonophthalmologist accuracy in diagnosing retinal hemorrhages in the shaken baby syndrome. J Pediatr. 2003;142:431–434. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2003.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel MB, Wetmore RF, Potsic WP, Handler SD, Tom LW. Mandibular fractures in the pediatric patient. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:533–536. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1991.01870170079017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H.Multilevel statistical models3rd ed.Edward Arnold: London; 2003 [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel K, Stoessel K, Leventhal JM, Ogle E, Teague B, Lavietes S, et al. Characteristics that distinguish accidental from abusive injury in hospitalized young children with head trauma. Pediatrics. 2004;114:165–168. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buys YM, Levin AV, Enzenauer RW, Elder JE, Letourneau MA, Humphreys RP, et al. Retinal findings after head trauma in infants and young children. Ophthalmology. 1992;99:1718–1723. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(92)31741-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinchon M, Defoort-Dhellemmes S, Desurmont M, Dhellemmes P. Accidental and nonaccidental head injuries in infants: A prospective study. J Neurosurg. 2005;102 (4 Suppl:380–384. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.102.4.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman KW, Bethel R, Shugerman RP, Grossman DC, Grady MS, Ellenbogen RG. The cause of infant and toddler subdural hemorrhage: A prospective study. Pediatrics. 2001;108:636–646. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre-Kahn V, Roche O, Dureau P, Uteza Y, Renier D, Pierre-Kahn A, et al. Ophthalmologic findings in suspected child abuse victims with subdural hematomas. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1718–1723. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinchon M, Defoort-Dhellemmes S, Noule N, Duhem R, Dhellemmes P. [Accidental or non-accidental brain injury in infants. Prospective study of 88 cases] La Presse Medicale. 2004;33:1174–1179. doi: 10.1016/s0755-4982(04)98886-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haviland J, Ross Russell RI. Outcome after severe non-accidental head injury. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77:504–507. doi: 10.1136/adc.77.6.504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenchs V, Curcoy AI, Navarro R, Pou J. Subdural haematomas and physical abuse in the first two years of life. Pediat Neurosurg. 2007;43:352–357. doi: 10.1159/000106382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agner C, Weig SG. Arterial dissection and stroke following child abuse: Case report and review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:416–420. doi: 10.1007/s00381-004-1056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold RW. Macular hole without hemorrhages and shaken baby syndrome: practical medicolegal documentation of children's eye trauma. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2003;40:355–357. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-20031101-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcenilla AIC, de la Maza V, Cuevas NC, Ballus MM, Castanera AS, Fernandez JP. When a funduscopic examination is the clue of maltreatment diagnostic. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22:495–496. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000227385.46143.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown SM, Bradley JC. Hemorrhagic posterior vitreous detachment without intraretinal hemorrhage in a shaken infant. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:1301. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.9.1301-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ells AL, Kherani A, Lee D. Epiretinal membrane formation is a late manifestation of shaken baby syndrome. J AAPOS. 2003;7:223–225. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(03)00005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner HB. A witnessed short fall mimicking presumed shaken baby syndrome (inflicted childhood neurotrauma) Pediat Neurosurg. 2007;43:433–435. doi: 10.1159/000106399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey K, Schrading W. A case of shaken baby syndrome with unilateral retinal hemorrhage with no associated intracranial hemorrhage. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24:616–617. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylton C, Goldberg MF. Circumpapillary retinal ridge in the shaken-baby syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:170. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm020098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert SR, Johnson TE, Hoyt CS. Optic nerve sheath and retinal hemorrhages associated with the shaken baby syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1986;104:1509–1512. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1986.01050220103037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lash SC, Williams CPR, Luff AJ, Hodgkins PR. 360 degree giant retinal tear as a result of presumed non-accidental injury. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:155. doi: 10.1136/bjo.88.1.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin AV, Magnusson MR, Rafto SE, Zimmerman RA. Shaken baby syndrome diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1989;5:181–186. doi: 10.1097/00006565-198909000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy I, Wysenbeek YS, Nitzan M, Nissenkorn I, Lerman-Sagle T, Steinherz R. Occult ocular damage as a leading sign in the battered child syndrome. Metab, Pediatr Syst Ophthalmol. 1990;13:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mierisch RF, Frasier LD, Braddock SR, Giangiacomo J, Berkenbosch LW. Retinal hemorrhages in an 8-year-old child: an uncommon presentation of abusive injury. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2004;20:118–120. doi: 10.1097/01.pec.0000113883.10140.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran K, Reddie I, Jacobs M. Severe haemorrhagic retinopathy and traumatic retinoschisis in a 2 year old infant, after an 11 metre fall onto concrete. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97 (suppl:149. [Google Scholar]

- Ogershok PR, Jaynes ME, Hogg JP. Delayed papilledema and hydrocephalus associated with shaking impact syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2001;40:351–354. doi: 10.1177/000992280104000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitetti RD, Maffei F, Chang K, Hickey R, Berger R, Pierce MC. Prevalence of retinal hemorrhages and child abuse in children who present with an apparent life-threatening event. Pediatrics. 2002;110:557–562. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl NG, Woodall BN. Hypothermia in shaken infant syndrome. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11:233–234. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199508000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse W, Enzenauer RW, Parmley VC. Inflammatory orbital tumor as an ocular sign of a battered child. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:510–512. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)71873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weidenthal DT, Levin DB. Retinal detachment in a battered infant. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81:725–727. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(76)90353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis A, Kodsi SR, Rubin SE, Esernio-Jenssen D, Ferrone PJ, McCormick SA. Subretinal hemorrhage masquerading as a hemorrhagic choroidal detachment in a case of nonaccidental trauma. J AAPOS. 2007;11:616–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arlotti SA, Forbes BJ, Dias MS, Bonsall DJ. Unilateral retinal hemorrhages in shaken baby syndrome. J AAPOS. 2007;11:175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2006.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JC, Liersch R, Tautz C, Schlueter B, Andler W. Shaken baby syndrome: report on four pairs of twins. Child Abuse Negl. 1998;22:931–937. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(98)00069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biron D, Shelton D. Perpetrator accounts in infant abusive head trauma brought about by a shaking event. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:1347–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo G, De Haller R, Metge F, Dureau P. Ischemic retinopathy and neovascular proliferation secondary to shaken baby syndrome. Retina. 2008;28 (suppl:42–46. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e318159ec91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JE, McCormick AQ. Whiplash shaking syndrome: retinal hemorrhages and computerized axial tomography of the brain. Child Abuse Negl. 1983;7:279–286. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(83)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CW, Taylor AA, Hertle RW, Duhaime AC. Retinal hemorrhages caused by accidental household trauma. J Pediatr. 1999;135:125–127. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drack AV, Petronio J, Capone A. Unilateral retinal hemorrhages in documented cases of child abuse. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:340–344. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhaime AC, Christian C, Armonda R, Hunter J, Hertle R. Disappearing subdural hematomas in children. Pediat Neurosurg. 1996;25:116–122. doi: 10.1159/000121108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder JE, Taylor RG, Klug GL. Retinal haemorrhage in accidental head trauma in childhood. J Paediatr Child Health. 1991;27:286–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1991.tb02539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes BJ, Cox M, Christian CW. Retinal hemorrhages in patients with epidural hematomas. J AAPOS. 2008;12:177–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaynon MW, Koh K, Marmor MF, Frankel LR. Retinal folds in the shaken baby syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:423–425. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90877-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangiacomo J, Barkett KJ. Ophthalmoscopic findings in occult child abuse. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1985;22:234–237. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19851101-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilles EE, Nelson MD. Cerebral complications of nonaccidental head injury in childhood. Pediat Neurol. 1998;19:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gnanaraj L, Gilliland MGF, Yahya RR, Rutka JT, Drake J, Dirks P, et al. Ocular manifestations of crush head injury in children. Eye. 2007;21:5–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han DP, Wilkinson WS. Late ophthalmic manifestations of the shaken baby syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1990;27:299–303. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19901101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfer RE, Scheurer SL, Alexander R, Reed J, Slovis TL. Trauma to the bones of small infants from passive exercise: a factor in the etiology of child abuse. J Pediatr. 1984;104:47–50. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80587-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor S, Schiffman J, Tang R, Kiang E, Li H, Woodward J. The significance of white-centered retinal hemorrhages in the shaken baby syndrome. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1997;13:183–185. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199706000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlin JD, Simons KB, Lazoritz S, Ruttum MS. Shaken baby syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1246–1254. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen PH. Traumatic retinal angiopathy. Report of six cases of Purtscher's disease. Acta Ophthalmol. 1965;43:776–786. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1965.tb07890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews GP, Das A. Dense vitreous hemorrhages predict poor visual and neurological prognosis in infants with shaken baby syndrome. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1996;33:260–265. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19960701-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe CF, Donahue SP. Prognostic indicators for vision and mortality in shaken baby syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118:373–377. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills M. Funduscopic lesions associated with mortality in shaken baby syndrome. J AAPOS. 1998;2:67–71. doi: 10.1016/s1091-8531(98)90066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad Y, Kim YM, Armstrong DC, Huyer D, Mian M, Levin AV. Correlation between retinal abnormalities and intracranial abnormalities in the shaken baby syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:354–359. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01628-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oral R, Yagmur F, Nashelsky M, Turkmen M, Kirby P. Fatal abusive head trauma cases. Consequence of medical staff missing milder forms of physical abuse. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:816–821. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e31818e9f5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi-Had H, Brandt JD, Rosas AJ, Rogers KK. Findings in older children with abusive head injury: does shaken-child syndrome exist. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e1039–e1044. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schloff S, Mullaney PB, Armstrong DC, Simantirakis E, Humphreys RP, Myseros JS, et al. Retinal findings in children with intracranial hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1472–1476. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm V, Landau K, Menke MN. Optical coherence tomography findings in shaken baby syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trenchs V, Curcoy AI, Morales M, Serra A, Navarro R, Pou J. Retinal haemorrhages in head trauma resulting from falls: differential diagnosis with non-accidental trauma in patients younger than 2 years of age. Childs Nerv Syst. 2008;24:815–820. doi: 10.1007/s00381-008-0583-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinchon M, Noizet O, Defoort-Dhellemmes S, Soto-Ares G, Dhellemmes P. Infantile subdural hematomas due to traffic accidents. Pediat Neurosurg. 2002;37:245–253. doi: 10.1159/000066216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson WS, Han DP, Rappley MD, Owings CL. Retinal hemorrhage predicts neurologic injury in the shaken baby syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1472–1474. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1989.01070020546037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morad Y, Avni I, Benton SA, Berger RP, Byerley JS, Coffman K, et al. Normal computerized tomography of brain in children with shaken baby syndrome. J AAPOS. 2004;8:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Ophthalmology Information Statement: Abusive Head Trauma/Shaken Baby SyndromeAvailable at one.aao.org/ce/practiceguidelines/clinicalstatements_content.aspx?cid=914163d5-5313-4c23-80f1-07167ee62579 . Accessed 10 November2011

- Mulvihill A, Buncic JR. Vertical sensory nystagmus associated with intraocular haemorrhages in the shaken baby syndrome. Eye. 2004;18:545–546. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhaime AC, Alario AJ, Lewander WJ, Schut L, Sutton LN, Seidl TS, et al. Head injury in very young children: Mechanisms, injury types, and ophthalmologic findings in 100 hospitalized patients younger than 2 years of age. Pediatrics. 1992;90:179–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill AO, Jones P, Tandon A, Fleck BW, Minns RA. An inter-observer and intra-observer study of a classification of RetCam images of retinal haemorrhages in children. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:99–104. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.168153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa TA, Skrinska R. Improved documentation of retinal hemorrhages using a wide-field digital ophthalmic camera in patients who experienced abusive head trauma. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155:1149–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams GG, Clark BJ, Fang S, Hill M. Retinal haemorrhages in an infant following RetCam screening for retinopathy of prematurity. Eye. 2004;18:652–653. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott AW, Farsiu S, Enyedi LB, Wallace DK, Toth CA. Imaging the infant retina with a hand-held spectral-domain optical coherence tomography device. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:364–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.