Abstract

We conducted 2 studies to determine whether dense and thin NCR schedules exert different influences over behavior and whether these influences change as dense schedules are thinned. In Study 1, we observed that thin as well as dense NCR schedules effectively decreased problem behavior exhibited by 3 individuals. In Study 2, we compared the effects of 2 NCR schedules in multielement designs, one with and the other without an extinction (EXT) component, while both schedules were thinned. Problem behavior remained low as the NCR schedule with EXT was thinned, but either (a) did not decrease initially or (b) subsequently increased as the NCR schedule without EXT was thinned. These results suggest that dense schedules of NCR decrease behavior by altering its motivating operation but that extinction occurs as the NCR schedule is thinned. The benefits and limitations of using dense or thin NCR schedules are discussed.

Key words: functional analysis, noncontingent reinforcement, self-injurious behavior, aggression, schedule effects, motivating operation, extinction

Noncontingent reinforcement (NCR), the delivery of reinforcers according to a schedule that is not response contingent, has been shown to be an effective treatment for a number of problem behaviors such as aggression, disruption, and self-injurious behavior (SIB; see Carr, Severtson, & Lepper, 2009, for a review). Applications of NCR typically begin with dense schedules of reinforcer delivery, which sometimes are nearly continuous and impractical to maintain. As a result, dense NCR schedules are thinned gradually to some interval considered to be feasible for implementation by therapists and teachers (usually a 5-min schedule).

Several procedures for thinning NCR schedules have been reported (Kahng, Iwata, DeLeon, & Wallace, 2000; Lalli, Casey, & Kates, 1997; Vollmer, Iwata, Zarcone, Smith, & Mazaleski, 1993). However, the thinning process may be time consuming; in addition, it is based on the assumption that dense schedules of NCR are necessary to produce initial reductions in problem behavior. Data to support this assumption were reported by Hagopian, Fisher, and Legacy (1994), who compared the effects of dense versus thin NCR schedules on problem behavior. The dense schedule greatly reduced all four subjects' problem behavior. The thin schedule produced a similar effect with one subject but moderate or inconsistent effects with the other three subjects. However, because the thin NCR schedule was implemented briefly (for 4 to 10 sessions across subjects), it is possible that the other subjects' behavior would have decreased further had the condition been continued. If thin NCR schedules eventually produce therapeutic reductions in problem behavior, then dense schedules, which initially are difficult to implement and subsequently may require protracted thinning sequences, might be avoided from the outset of treatment.

The initial purpose of this study was to extend the research of Hagopian et al. (1994) by comparing the effects of dense and thin NCR schedules while implementing the thin schedule long enough to determine whether it would produce a therapeutic outcome and, if so, how many sessions would be required. Our results (Study 1) showed that both schedules quickly reduced problem behavior, raising the question of how the schedule of NCR influences behavior. Therefore, we conducted a further analysis (Study 2) to clarify the mechanisms by which dense and thin NCR schedules reduce behavior.

It is commonly acknowledged that decreases in responding under NCR may result from either (a) elimination of the motivating operation (MO) to engage in behavior (in the present case, deprivation) due to the delivery of free reinforcers or (b) elimination of the response–reinforcer contingency that maintains behavior, which produces extinction (EXT; see Wallace & Weil, 2005, for a more extended discussion). The relative contributions of these MO and EXT influences are difficult to determine when NCR is implemented according to dense schedules because the processes typically are confounded. That is, reinforcement is delivered both frequently and independent of the occurrence of the problem behavior (MO influence), and problem behavior no longer produces reinforcement (EXT influence).

Data that indicate that NCR can decrease behavior solely by altering the MO for responding have been reported in several studies in which NCR was implemented without EXT (Fischer, Iwata, & Mazaleski, 1997; Fisher, O'Connor, Kurtz, DeLeon, & Gotjen, 2000; Hagopian, Crockett, van Stone, DeLeon, & Bowman, 2000). However, MO influences evident under dense NCR schedules might not account for continued behavioral suppression as NCR schedules are thinned. In most research in which initially dense NCR schedules were thinned, temporary increases in problem behavior have been observed (e.g., Hagopian et al., 1994; Kahng, Iwata, DeLeon, et al., 2000; Vollmer et al., 1998). Although these increases may have reflected behavioral variability or artifacts of NCR schedules such as adventitious reinforcement, they also may have indicated the point at which the NCR schedule was too thin to produce an MO type of effect and at which the absence of contingent reinforcement produced EXT. Results of Hagopian et al. (2000) provide the clearest evidence that MO influences on behavior diminish as NCR schedules are thinned. After observing rapid decreases in the problem behavior of three subjects (the fourth subject was not included in the NCR analysis) under dense NCR schedules that were implemented without EXT, the authors thinned the NCR schedules and observed large increases in problem behavior in every case. Therapeutic effects were recovered when EXT was added to the NCR schedules. The loss of control by NCR without EXT as the schedules were thinned raises the possibility that response suppression under the thin NCR schedules (with EXT) was solely a function of EXT.

In a related study, Hagopian, Toole, Long, Bowman, and Lieving (2004) compared the effects of two differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) schedules, both containing EXT, on the problem behavior of one subject. One schedule (dense to thin) was initially set at 15 s and was thinned to 4 min; the other schedule (thin) was set at the terminal value (4 min) from the beginning of treatment. Periodic increases in responding were observed under both schedules, but the end-of-treatment criterion was reached faster under the thin schedule. Hagopian et al. suggested that the superiority of the thin schedule may have been due to the fact that it exposed the subject to EXT at the outset, whereas the dense schedule did not permit sufficient exposure to EXT until the schedule was thinned. Although the study focused on the effects of DRA rather than NCR, the relative influences of reinforcement and EXT would seem to apply to NCR thinning as well.

Kahng, Iwata, Thompson, and Hanley (2000) examined potential MO versus EXT effects associated with NCR by observing rates of problem behavior for 20-min periods at the end of NCR sessions, when no reinforcers were delivered. If NCR had exerted an MO influence on behavior during the session, an increase in problem behavior would be expected during the 20-min postsession period of deprivation. By contrast, if NCR had resulted in EXT during the session, no increase in problem behavior would be expected during the subsequent 20 min because EXT already had occurred. The authors observed idiosyncratic effects across three subjects that did not permit clear conclusions. In addition, their analysis was indirect because it was based on postsession patterns of responding when NCR was not in effect. In other words, the procedure did not involve a comparison of NCR with and without extinction under either dense or thin schedules.

Study 2 was designed to provide a direct comparison of the effects of NCR schedule thinning with and without EXT. We began by alternating two dense schedules of NCR; one included EXT, but the other did not. Assuming that response suppression would be observed in both conditions, it would have to be attributed to an MO influence due to the absence of EXT in one of the schedules. We subsequently thinned both schedules. Inability of the MO-altering component of NCR to maintain response suppression would be evident if problem behavior increased as the NCR schedule without EXT was thinned (i.e., fewer reinforcer deliveries would occasion responding, which then would contact its maintaining contingency). By contrast, thinning the NCR schedule with EXT should result in either continued response suppression or only a temporary increase in problem behavior.

GENERAL METHOD

Subjects and Setting

Three individuals who lived in a state residential facility for persons with intellectual disabilities participated. All had been referred for treatment of SIB or aggression. Shelby previously participated in Conners et al. (2000; assessment only); Susan and Matt participated in Kahng, Iwata, Thompson, et al. (2000) and were included in this study due to treatment relapse. Shelby was a 29-year-old woman who had been diagnosed with profound intellectual disability and who engaged in face slapping, body hitting, and hand biting. She responded to a few one-step instructions but had no expressive verbal skills. Susan was a 32-year-old woman who had been diagnosed with profound intellectual disability and who engaged in both SIB (banging her limbs against hard surfaces) and aggression (hitting others). She responded to a few one-step directions and used gestures to communicate. Matt was a 35-year-old man who had been diagnosed with profound intellectual disability and who engaged in hand and arm biting. He followed some instructions and used a few signs and gestures to communicate his needs. None of the subjects had any visual or auditory impairment. Shelby and Matt were ambulatory; Susan did not walk independently and spent most of her time in a wheelchair.

All sessions were conducted in therapy rooms at a day-treatment program located on the grounds of the residential facility. Rooms contained tables, chairs, and materials necessary for conducting each condition.

Response Measurement and Reliability

The dependent variables were SIB or SIB and aggression, which were defined as follows: body hitting (Shelby): audible contact of an open hand against the body; biting (Shelby and Matt): closure of the upper and lower teeth on the hand or arm; hand banging (Susan): audible contact of a hand or wrist against a hard surface; and aggression (Susan): hitting, kicking, pinching, or scratching the therapist. Data also were collected on subjects' compliance with instructions, subjects' appropriate interaction with play materials, and therapists' delivery of attention, instructions, materials, or edible items (data available from the first author).

Trained observers used handheld computers to collect data on the frequency of problem behaviors. Data for all subjects' SIB or aggression were summarized as responses per minute. A second observer simultaneously but independently recorded data during 48% of the sessions in Study 1 and 38% of the sessions in Study 2. Reliability was calculated by dividing session time into consecutive 10-s intervals and comparing observers' records on an interval-by-interval basis. The smaller number of responses in each interval was divided by the larger number of responses; these fractions then were averaged across all intervals. Mean agreement scores across subjects were 96% in Study 1 (range of individual sessions, 79% to 100%) and 95% in Study 2 (range, 85% to 100%).

Functional Analysis

A functional analysis (FA; Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982/1994) had been conducted previously for all subjects to verify that their problem behaviors were maintained by social-positive reinforcement (see Conners et al., 2000, for Shelby's FA results, and Kahng, Iwata, Thompson, et al., 2000, for Matt's and Susan's results). Shelby and Matt engaged in problem behavior most frequently during the tangible condition; Susan engaged in SIB and aggression most frequently during the attention condition. Informal observations conducted prior to the study indicated that these functions had not changed. Thus, all subjects' problem behaviors were maintained by social-positive reinforcement.

Study 1: Dense Versus Thin NCR Schedules

Method

All sessions lasted 10 min. Three to five sessions were conducted daily, usually 4 to 5 days per week. Following baseline, two NCR schedules were implemented in a multiple baseline design across subjects. Two therapists conducted each subject's baseline and NCR sessions in therapy rooms that were painted in different colors to facilitate discrimination. Baseline and NCR conditions were alternated in a multielement design (a reversal design also was used with Shelby). The comparison was concluded when either schedule resulted in five sessions with problem behavior below 0.5 responses per minute on a fixed-time (FT) 5-min schedule of reinforcer delivery.

Baseline

Baseline contingencies were identical to those of the FA conditions that resulted in the highest rates of problem behavior. The therapist delivered brief attention (approximately 5 s) contingent on Susan's SIB or aggression and delivered a small amount (one to three pieces) of cereal and candy contingent on Shelby's and Matt's SIB, respectively. A fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule of reinforcer delivery for problem behavior was in effect throughout the session.

Thin NCR

One therapist delivered the maintaining reinforcer for problem behavior on an FT 5-min schedule. Problem behavior did not result in any programmed reinforcement.

Dense-to-thin NCR

The other therapist delivered the maintaining reinforcer for problem behavior on an FT schedule that was dense initially but was thinned across sessions. Shelby's and Matt's initial NCR schedules were based on their interresponse times (IRTs) for problem behavior during baseline (3 s and 6 s, respectively); Susan's initial NCR schedule was set at FT 10 s. The NCR schedules were thinned if problem behavior was below 0.5 responses per minute for two consecutive sessions, and continued to be thinned until either (a) the terminal FT 5-min value was reached, or (b) criterion was reached under the thin NCR schedule. Shelby's initial FT 3-s schedule was not thinned because the thin schedule immediately suppressed behavior to near-zero levels. Susan's schedule was thinned from FT 10 s to FT 12 s and 15 s. Matt's schedule was thinned from FT 6 s to FT 10 s, 12 s, 15 s, and 20 s. No programmed reinforcement was delivered contingent on problem behavior.

Results and Discussion

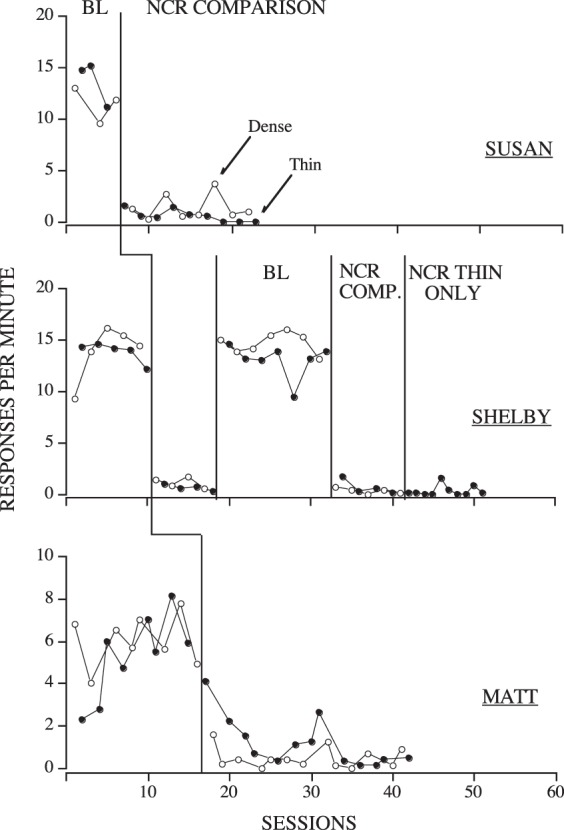

Figure 1 shows results of the NCR comparison for all subjects. Susan's problem behavior averaged 12 responses per minute during baseline. Both NCR schedules (thin and dense to thin) resulted in immediate suppression of problem behavior. Because her problem behavior under the thin NCR schedule met the termination criterion when the dense-to-thin schedule had only been thinned to an FT 15 s, her dense-to-thin schedule was not thinned any further. Shelby's SIB averaged 13.8 responses per minute during her first baseline and decreased immediately to near-zero rates when both NCR schedules were introduced. Her SIB increased to a mean of 13.8 responses per minute during her second baseline and decreased again when the two NCR schedules were reimplemented. To add a measure of control for interaction effects (due to the alternating dense and thin schedules), we subsequently implemented only the thin NCR condition and observed no increase in Shelby's SIB. Matt's SIB averaged 15.6 responses per minute during baseline. His SIB decreased quickly under the dense-to-thin NCR schedule and more gradually (across five sessions) under the thin NCR schedule. His SIB met the termination criterion under the thin NCR schedule when the dense-to-thin schedule had been thinned to FT 20 s.

Figure 1. .

Responses per minute of problem behavior during baseline and NCR sessions (Study 1) exhibited by Susan, Shelby, and Matt.

Results of this study indicate that thin NCR schedules may, in some cases, be effective in decreasing problem behavior. Our original plan was to conduct the thin NCR (5-min) condition long enough to determine whether problem behavior eventually would decrease. However, we observed that the thin (FT 5-min) schedule produced immediate and large decreases in the problem behavior of all three subjects; in two of these cases (Susan and Shelby), the effects observed under the thin schedule were indistinguishable from those observed under the dense schedule. Although Matt's SIB decreased more gradually under the thin schedule, it reached the end-of-treatment criterion (five sessions with responding below 0.5 responses per minute) under the thin schedule when his dense schedule had been thinned to only FT 20 s. Thus, our findings were somewhat different than those reported by Hagopian et al. (1994), who observed consistent decreases in problem behavior under the FT 5-min NCR schedule with just one of four subjects. Several factors may have accounted for these differences. First, two of our subjects (Matt and Susan) had a previous history of treatment with both NCR and EXT; thus, their behavior may have been more sensitive to the thin NCR schedule. However, Shelby, whose SIB decreased immediately almost to zero under the thin schedule, had not been exposed previously to NCR, nor apparently had the subject in the Hagopian et al. study (see Figure 2, Lynn), whose problem behavior showed similar reductions.

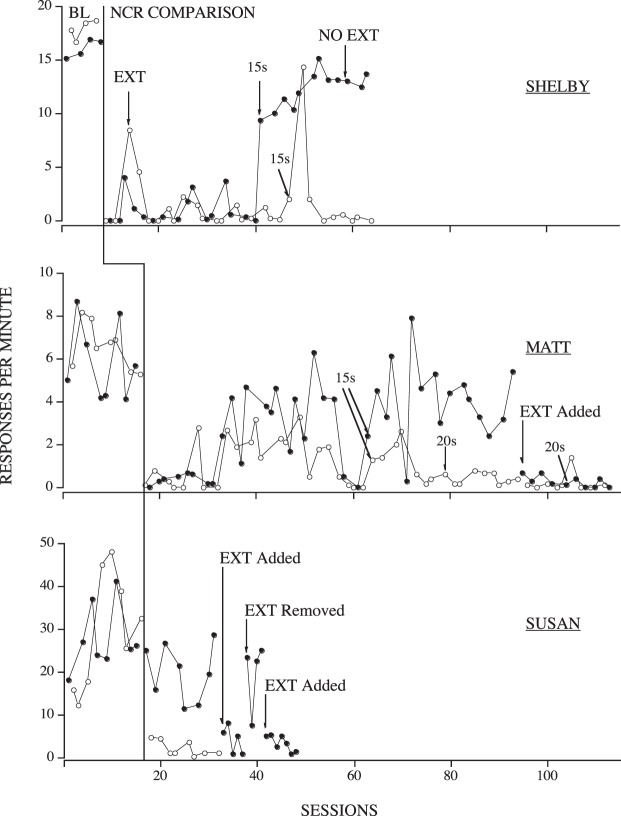

Figure 2. .

Responses per minute of problem behavior during baseline, NCR with extinction, and NCR without extinction (Study 2) for Shelby, Matt, and Susan.

Second, the rapidly changing conditions of the multielement comparison may have produced a carryover effect from dense NCR to thin NCR sessions. Although this possibility cannot be ruled out, steps were taken to minimize such effects in this study (the two types of sessions were conducted by different therapists in different rooms), and Shelby's SIB showed no increase during the final condition in which she was exposed only to the thin NCR schedule. Third, some combination of factors, including those just noted as well as other uncontrolled historical events, may have accounted for the more consistent reductions in problem behavior shown by our subjects under thin NCR schedules.

Study 2: Comparison of NCR Schedule Thinning with and without Extinction

Method

Subjects, therapist arrangement, and session schedules were the same as in Study 1. Following baseline, two dense schedules of NCR were implemented in a multiple baseline across subjects design. One schedule contained EXT, and the other did not; these were alternated in a multielement design. Additional manipulations were undertaken with Matt and Susan (see details in the Results section).

Baseline

Baseline conditions were the same as those used in the baseline of Study 1.

NCR without EXT (NCR/CR)

Problem behavior resulted in delivery of the maintaining reinforcer (attention for Susan, edible items for Shelby and Matt) on an FR 1 schedule, as in baseline. These consequences also were delivered on an FT schedule, with the initial schedule based on the baseline IRT of problem behavior. The NCR schedule was thinned if problem behavior was below 0.5 responses per minute for two consecutive sessions. Shelby's NCR schedule started at FT 2 s (30 reinforcers per minute) and was thinned to FT 3, 4, 6, 12, and finally 15 s by eliminating five reinforcers per minute until FT 12 s (five reinforcers per minute), at which point thinning continued by removing one reinforcer per minute. The same procedure was used to thin Matt's NCR schedule, which was set initially set at FT 5 s (12 reinforcers per minute) and then thinned to FT 6, 12, 15, and finally 20 s. Susan's NCR schedule was initially an FT 1-s schedule and was not thinned because her problem behavior never decreased to the point of meeting the thinning criterion.

NCR with EXT (NCR/EXT)

No programmed reinforcement was delivered contingent on problem behavior (i.e., problem behavior was placed on extinction). The maintaining reinforcer was delivered on an FT schedule; however, if problem behavior occurred contiguous with a scheduled reinforcer delivery, that reinforcer was omitted. The initial schedules and the procedures used for thinning were identical to those described for the NCR/CR condition.

Results and Discussion

Figure 2 shows results of the NCR comparison with and without EXT. Shelby's SIB averaged 17 responses per minute during baseline. The dense NCR schedule, both with and without EXT, initially produced large reductions in her SIB. When the NCR schedule in the NCR/CR condition was thinned to FT 15 s, however, her SIB increased noticeably and was maintained. By contrast, when NCR/EXT was thinned to 15 s, SIB increased only for one session; thereafter, it decreased to its previous low rate. Matt's SIB averaged 6.2 responses per minute during baseline and decreased immediately when the dense NCR schedules with and without EXT were implemented. However, his SIB increased and became more variable as both NCR schedules were thinned. When the NCR schedules were thinned to FT 15 s, SIB was maintained in the NCR/CR condition but eventually decreased in the NCR/EXT condition. As a further test of the influence of extinction, we then added EXT to the condition in which it originally was absent (NCR/CR became NCR/EXT), and SIB decreased to near-zero rates. Susan's SIB and aggression averaged 28.7 responses per minute during baseline. The dense NCR schedules produced results that were different than those observed for Shelby and Matt. A large and rapid decrease in problem behavior occurred under the NCR/EXT schedule. By contrast, NCR/CR had little or no effect on her behavior. We then added EXT to the condition in which it originally was absent (NCR/CR became NCR/EXT), removed it, and added it again in a reversal design, and observed low rates of problem behavior only during NCR conditions that included EXT.

In summary, dense schedules of NCR/EXT suppressed the problem behavior of all subjects. The dense schedule of NCR/CR had no effect on Susan's problem behavior, suggesting that extinction was a necessary component of her treatment from the outset. Most relevant to the present study were the results obtained for Shelby and Matt. Their patterns of responding under NCR/EXT and NCR/CR over the course of treatment revealed differences in the ways that dense and thin NCR schedules influence behavior.

The dense NCR schedule was effective for Shelby and Matt regardless of whether problem behavior was reinforced. These results were similar to those reported by Hagopian et al. (2000) under dense NCR/CR schedules and cannot be attributed to extinction. Thus, dense NCR schedules appear to reduce behavior by altering the MO that occasions responding. This motivational influence, however, appears to weaken as NCR schedules are thinned. When Shelby's and Matt's NCR/CR schedule was thinned to FT 15 s, their problem behavior increased, suggesting that the MO-altering effects of NCR no longer maintained response suppression. The fact that their problem behavior continued to occur in the NCR/CR condition but did not in the NCR/EXT condition seems to be consistent with a conclusion that low rates of problem behavior under thin NCR schedules were a direct function of EXT. It was interesting to observe that Shelby's and Matt's problem behavior was more sensitive to the antecedent effects of the delivery of frequent reinforcers under dense NCR; by contrast, their behavior was more sensitive to reinforcers delivered (or not delivered) as a consequence under thinner NCR.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Results of the present studies indicate that relatively thin NCR schedules may effect reductions in problem behavior that approximate those obtained with dense NCR schedules (Study 1) but that the two types of schedules exert different influences over behavior (Study 2). Dense NCR schedules appear to be effective because they eliminate the MO for responding; by contrast, thin NCR schedules produce extinction. These results have practical implications and extend the findings of previous research by clarifying the mechanisms by which NCR reduces behavior.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that dense NCR schedules can be thinned successfully. However, except for the studies by Hagopian et al. (1994, 2004), previous research has not evaluated the therapeutic effects of thin NCR schedules from the outset of treatment. Results of Study 1 showed that reductions in problem behavior under thin NCR (FT 5-min) schedules were very similar to those observed under dense NCR (nearly continuous) schedules. Although our results did not replicate the findings of Hagopian et al. (1994) and therefore should be interpreted with caution, they suggest that the choice of whether to begin treatment with dense or thin NCR schedules may be partially a practical one. For example, if treatment time is limited, a thin NCR schedule might be attempted first, with a dense schedule used only if needed. Thin NCR schedules also may be advantageous if a goal of treatment is to strengthen alternative behavior. Because dense NCR schedules may interfere with attempts to establish appropriate behavior using the same reinforcer as that delivered during NCR (Goh, Iwata, & DeLeon, 2000), use of an initially thinner NCR schedule (or, alternatively, rapid schedule thinning) might facilitate acquisition of appropriate behavior. By contrast, a dense NCR schedule may advisable when attempting to treat extremely dangerous behavior such as severe aggression or SIB, because dense schedules may facilitate rapid response reduction (Hagopian et al., 1994) or reduce the likelihood of extinction bursts (Vollmer et al., 1998). We must note, however, that these implications are drawn from several lines of research that were not addressed in the present study; thus, additional direct comparisons under varied yet controlled conditions are warranted.

Results of Study 2 suggested that dense NCR schedules reduce behavior primarily by altering the MO that occasions responding, whereas thin NCR schedules reduce behavior through extinction. Moreover, the increases observed in Shelby's and Matt's problem behaviors as the NCR schedules were thinned revealed the transition point between these two processes. Both subjects' problem behavior was maintained under the NCR/CR schedule, indicating that the MO-altering component of NCR no longer influenced behavior, which once again contacted the reinforcement contingency that maintained responding. By contrast, increases in problem behavior were temporary as the NCR/EXT schedule was thinned, indicating that problem behavior was not maintained in the absence of reinforcement. These results have several implications for treatment.

First, because Shelby's and Matt's (but not Susan's) data indicated that dense NCR schedules were effective in decreasing problem behavior in spite of the fact that it continued to be reinforced, extinction may be unnecessary if NCR can be delivered according to relatively dense schedules. This has also been shown in several previous studies (Fischer et al., 1997; Fisher et al., 2000; Hagopian et al., 2000). Although reinforcement for problem behavior is undesirable, it may be unavoidable occasionally if the behavior is severe and requires immediate interruption. Second, however, Shelby's and Matt's data, as well as in those reported by Hagopian et al. (2000), suggest that if the reinforcing consequences for problem behavior cannot be withheld, NCR schedule thinning may be unsuccessful (but see Lalli et al., 1997, for an exception). Third, extinction appears to be an important component, and may be the only active component, of thin NCR schedules. This finding, evident in Shelby's and Matt's data and also in the data reported by Hagopian et al. (2000), is significant because NCR often is described as an antecedent intervention that reduces behavior primarily through its MO-altering effects. Relevant to this finding are the data reported by Vollmer et al. (1993), in which the effects of NCR and differential reinforcement of other behavior (DRO) were compared. Both procedures included extinction and initially were implemented under dense schedules that were thinned gradually. The authors concluded that therapeutic effects observed at the terminal DRO schedule (5 min) were due to extinction because rates of reinforcement were so low (ranging from 0 to 0.4 reinforcers per 5-min interval). However, rates of reinforcement under the 5-min NCR schedule also were sufficiently low (one reinforcer per 5-min interval) to be incidental. Thus, the thin schedule of NCR, as well as the thin schedule of DRO, may have amounted to extinction. Finally, to the extent that extinction is an integral component of NCR, such that response bursting may occur while the NCR schedule is thinned, dense NCR schedules may simply delay an inevitable problem that will arise as maintenance schedules are implemented. This pattern of behavior was observed for one of our subjects (Shelby) in Study 2, whose problem behavior increased dramatically (although temporarily) as the NCR/EXT condition was thinned.

NCR schedule thinning can be associated with other effects that may or may not have been reflected in our data. For example, Matt and Shelby exhibited somewhat higher or more variable levels of problem behavior during NCR (with extinction) in Study 2 than in Study 1. A number of variables may have been responsible for these differences, including historical effects, rapid alternation between extinction and no-extinction conditions in Study 2, or the relatively brief duration of conditions in Study 1. Another possibility is that NCR thinning during Study 2 may have produced adventitious reinforcement of problem behavior if response rates periodically coincided with reinforcement rates. Although reinforcers were withheld if problem behavior occurred, higher levels of responding in Study 2 may have resulted in briefer delays between problem behavior and the delivery of a reinforcer than was the case in Study 1, due to the fact that responding decreased so quickly in Study 1. Susan's data from Study 2 also may have reflected the influence of adventitious reinforcement. She engaged in high rates of problem behavior under the NCR/CR schedule even when reinforcers were delivered continuously, a curious finding if frequent reinforcer deliveries decrease responding due to an MO influence. It is possible, however, that her rate of SIB during baseline was sufficiently high that the transition from baseline to NCR/CR was indistinguishable. By contrast, Susan's NCR/EXT procedure imposed a contingent delay when SIB occurred, perhaps serving a time-out function.

The present conclusions must be tempered for several reasons. First, patterns of responding observed during the thin NCR condition in Study 1 differed from those reported by Hagopian et al. (1994): We observed immediate and large decreases in problem behavior in two of three subjects, whereas Hagopian et al. observed similar results with only one of four subjects. Although behavioral suppression under extinction sometimes produces gradual response suppression, results from a number of studies have shown that suppression under extinction can be immediate (e.g., Kuhn, DeLeon, Fisher, & Wilke, 1999; Sajwaj, Twardosz, & Burke, 1972; Shukla & Albin, 1996) and can occur without evidence of other side effects such as bursting (Lerman & Iwata, 1996; Lerman, Iwata, & Wallace, 1999). Second, because our subjects had been exposed to extinction in previous studies, it is possible that the rapid decreases observed in their problem behavior under the thin NCR schedule could have reflected an historical influence (although their levels of SIB prior to this study and during baseline suggested that such an effect was weak). Finally, the unusual patterns of responding noted above may have been due to a number of influences whose identification will require additional control procedures. For example, adventitious reinforcement, rather than being invoked based on post hoc data examination, is better studied as a directly manipulated variable.

In summary, data from the present studies support the widely held assumption that NCR can decrease behavior by altering its MO. Some qualifications are required, however, based on our results from Study 2. First, when NCR is implemented as the sole intervention (and consequences for problem behavior remain unchanged), its MO influence on behavior seems to be dependent on frequent reinforcer deliveries. Second, when NCR is implemented with EXT, its effectiveness under thin schedules seems to result from EXT and is unrelated to NCR delivery. Identification of these separate influences is important because NCR generally is regarded as an antecedent intervention. In practice, however, NCR typically includes an EXT component, which seems to be critical during the NCR thinning process. Thus, perhaps a more correct label for NCR interventions used in most studies on treatment of problem behavior is NCR/EXT.

Footnotes

Action Editor, Dorothea Lerman

REFERENCES

- Carr J. E, Severtson J. M, Lepper T. L. Noncontingent reinforcement as an empirically supported treatment for problem behavior exhibited by individuals with developmental disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities. (2009);30:44–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2008.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners J, Iwata B. A, Kahng S, Hanley G. P, Worsdell A. S, Thompson R. H. Differential responding in the presence and absence of discriminative stimuli during multielement functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (2000);33:299–308. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-299. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer S. M, Iwata B. A, Mazaleski J. L. Noncontingent delivery of arbitrary reinforcers as treatment for self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1997);30:239–249. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-239. doi:10.1901/jaba.1997.30-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W. W, O'Connor J. T, Kurtz P. F, DeLeon I. G, Gotjen D. L. The effects of noncontingent delivery of high- and low-preference stimuli on attention-maintained destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (2000);33:79–83. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-79. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh H, Iwata B. A, DeLeon I. G. Competition between noncontingent and contingent reinforcement schedules during response acquisition. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (2000);33:195–205. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-195. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Crockett J. L, van Stone M, DeLeon I. G, Bowman L. G. Effects of noncontingent reinforcement on problem behavior and stimulus engagement: The role of satiation, extinction, and alternative reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (2000);33:433–449. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-433. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Fisher W. W, Legacy S. M. Schedule effects of noncontingent reinforcement on attention-maintained destructive behavior in identical quadruplets. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1994);27:317–325. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-317. doi:10.1901/jaba.1994.27-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Toole L. M, Long E. S, Bowman L. G, Lieving G. A. A comparison of dense-to-lean and fixed lean schedules of alternative reinforcement and extinction. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (2004);37:323–337. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-323. doi:10.1901/jaba.2004.37-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B. A, Dorsey M. F, Slifer K. J, Bauman K. E, Richman G. S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1994);27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. doi:10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197 (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities,2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng S, Iwata B. A, DeLeon I. G, Wallace M. D. A comparison of procedures for programming noncontingent reinforcement schedules. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (2000);33:223–231. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-223. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng S, Iwata B, Thompson R, Hanley G. A method for identifying satiation versus extinction effects under noncontingent reinforcement schedules. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (2000);33:419–432. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-419. doi:10.1901/jaba.2000.33-419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn D. E, DeLeon I. G, Fisher W. W, Wilke A. E. Clarifying an ambiguous functional analysis with matched and mismatched extinction procedures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1999);32:99–102. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-99. doi:10.1901/jaba.1999.32-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalli J. S, Casey S. D, Kates K. Noncontingent reinforcement as treatment for severe problem behavior: Some procedural variations. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1997);30:127–137. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-127. doi:10.1901/jaba.1997.30-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D. C, Iwata B. A. A methodology for distinguishing between extinction and punishment effects associated with response blocking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1996);29:231–233. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-231. doi:10.1901/jaba.1996.29-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D. C, Iwata B. A, Wallace M. D. Side effects of extinction: Prevalence of bursting and aggression during the treatment of self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1999);32:1–8. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-1. doi:10.1901/jaba.1999.32-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajwaj T, Twardosz S, Burke M. Side effects of extinction procedures in a remedial preschool. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1972);5:163–175. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1972.5-163. doi:10.1901/jaba.1972.5-163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S, Albin R. W. Effects of extinction alone and extinction plus functional communication training on covariation of problem behaviors. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1996);29:565–568. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1996.29-565. doi:10.1901/jaba.1996.29-565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T. R, Iwata B. A, Zarcone J. R, Smith R. G, Mazaleski J. L. The role of attention in the treatment of attention-maintained self-injurious behavior: Noncontingent reinforcement and differential reinforcement of other behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1993);26:9–21. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-9. doi:10.1901/jaba.1993.26-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer T. R, Progar P. R, Lalli J. S, Van Camp C. M, Sierp B. J, Wright C. S, et al. Fixed-time schedules attenuate extinction-induced phenomena in the treatment of severe aberrant behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (1998);31:529–542. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-529. doi:10.1901/jaba.1998.31-529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M. D, Weil T. M. Noncontingent reinforcement: Mechanisms involved in response suppression and treatment efficacy. European Journal of Behavior Analysis. (2005);6:71–82. [Google Scholar]