Abstract

STUDY QUESTION

Is asthma more common in children born after subfertility and assisted reproduction technologies (ART)?

SUMMARY ANSWER

Yes. Asthma, wheezing in the last year and anti-asthmatic medication were all more common in children born after a prolonged time to conception (TTC). This was driven specifically by an increase in children born after ART.

WHAT IS KNOWN ALREADY

Few studies have investigated any association between ART and asthma in subsequent children, and findings to date have been mixed. A large registry-based study found an increase in asthma medication in ART children but suggests underlying infertility is the putative risk factor. Little is known about asthma in children after unplanned or mistimed conceptions.

STUDY DESIGN, SIZE, DURATION

The Millennium Cohort Study is a UK-wide, prospective study of 18 818 children recruited at 9 months of age. Follow-up is ongoing. This study analyses data from follow-up surveys at 5 and 7 years of age (response rates of 79 and 70%, respectively).

PARTICIPANTS/MATERIALS, SETTING, METHODS

Singleton children whose natural mothers provided follow-up data were included. Mothers reported whether their pregnancy was planned; planners provided TTC and details of any ART. The population was divided into ‘unplanned’ (unplanned and unhappy), ‘mistimed’ (unplanned but happy), ‘planned’ (planned, TTC < 12 months), ‘untreated subfertile’ (planned, TTC >12 months), ‘ovulation induced’ (received clomiphene citrate) and ‘ART’ (IVF or ICSI). The primary analysis used the planned children as the comparison group; secondary analysis compared the treatment groups to the children born to untreated subfertile parents. Outcomes were parent report of asthma and wheezing at 5 and 7 years, derived from validated questions in the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, plus use of anti-asthmatic medications. A total of 13 041 (72%) children with full data on asthma and confounders were included at 5 years of age, and 11 585 (64%) at 7 years.

MAIN RESULTS AND THE ROLE OF CHANCE

Compared with planned children, those born to subfertile parents were significantly more likely to experience asthma, wheezing and to be taking anti-asthmatics at 5 years of age [adjusted odds ratio (OR): 1.39 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.07, 1.80), OR: 1.27 (1.00, 1.63) and OR: 1.90 (1.32,2.74), respectively]. This association was mainly related to an increase among children born after ART (adjusted OR: 2.65 (1.48, 4.76), OR: 1.97, (1.10, 3.53) and OR: 4.67 (2.20, 9.94) for asthma, wheezing and taking anti-asthmatics, respectively). The association was also present, though reduced, at the age of 7 years.

LIMITATIONS, REASONS FOR CAUTION

The number of singletons born after ART was relatively small (n = 104), and as such the findings should be interpreted with caution. However, data on a wide range of possible confounding and mediating factors were available and analysed. The data were weighted for non-response to minimize selection bias.

WIDER IMPLICATIONS OF THE FINDINGS

The findings add to the growing body of evidence suggesting an association between subfertility, ART and asthma in children. Further work is needed to establish causality and elucidate the underlying mechanism. These findings are generalizable to singletons only, and further work on multiples is needed.

STUDY FUNDING/COMPETING INTEREST(S)

This study was funded by a Medical Research Council project grant. No competing interests.

Keywords: infertility, assisted reproduction techniques, asthma, unplanned pregnancy

Introduction

Asthma is a chronic, complex, obstructive lung disease characterized by acute symptomatic episodes of bronchial restriction, breathlessness and wheezing. The prevalence of childhood asthma is high in the UK: approximately one in five children are diagnosed by a doctor, making it one of the most common chronic childhood conditions (Kaur et al., 1998; Patel et al., 2008). Asthma can limit a child's daily life, social activities and may result in missed school days which then impacts on parents working life (Sennhauser et al., 2005). Children with asthma require more contact with doctors than non-sufferers, and may require medication and hospitalization. In 2003, it was estimated that 1–5-year-old children with wheezing in the UK cost the health service a total of £53 million (Stevens et al., 2003).

There is still limited understanding of the aetiology of asthma but there are many identified risk factors for the condition, including prenatal, environmental and genetic factors, and gene-by-environment interactions (Subbarao et al., 2009). Pregnancy-related risk factors for asthma include preterm birth, low birthweight and Caesarean delivery. A recent, large registry-based study of Swedish children concluded that those born after assisted reproduction techniques (ART), such as IVF, were more likely to be prescribed anti-asthmatic medication compared with naturally conceived children but the underlying duration of subfertility appeared to be the putative risk factor rather than an effect of treatment (Kallen et al., 2012). Others analysing Scandinavian registry data have also reported a significant increase in the use of asthma medications and hospitalization among children conceived after infertility treatment (Ericson et al., 2002; Koivurova et al., 2007; Finnstrom et al., 2011), though some researchers have found no effect (Pinborg et al., 2003; Klemetti et al., 2006). Smaller clinic-based studies in Turkish and American populations have found no increased risk of asthma after infertility treatment (Cetinkaya et al., 2009; Sicignano et al., 2010). The inconsistent results could be related to variations in participation rates, consideration of confounding factors and differing measures of asthma, such as prescription records or self-report.

In this study we assess the effects of pregnancy planning, time to conception (TTC) and ART on asthma and wheezing in children at 5 and 7 years of age. We present findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study (MCS), one of the few large observational studies where data are available on conception status, asthma diagnosis and key confounding factors.

Materials and Methods

The MCS

The MCS is a nationally representative prospective cohort study of 18 818 children across the UK (Hansen, 2008). A random two-stage sample of all infants born in 2000–2002, and resident in the UK at 9 months, was drawn from the Department of Social Security Child Benefit Registers. Baseline interviews captured socio-demographic and health data, including information on pregnancy and infertility treatment, and the children were subsequently followed up at 3, 5 and 7 years. Data for 5 and 7 years are presented here. Ethical approval for the Millennium Cohort Study was granted from the multi-centre research ethics committee.

Conception history

Mothers were asked if they had planned to conceive, and how they felt when they discovered they were pregnant. ‘Planners’ were then asked how long they took to conceive and if they received fertility treatment. Women were grouped into the following categories:

unplanned (unplanned, unhappy about pregnancy);

mistimed (unplanned, happy about pregnancy);

planned (planned, TTC <12 months);

untreated subfertile (planned, TTC >12 months);

ovulation induction (OI) (planned, used ovulation inducing drugs such as clomiphene citrate);

ART (planned, used ART such as IVF or ICSI).

Asthma and wheezing illness outcomes

At 5 and 7 years mothers were asked about asthma and wheezing illnesses including occurrence, frequency and severity indicators for each child. The questions were taken from the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) core questionnaire for asthma. This validated instrument has been widely used to measure childhood asthma and wheezing illnesses (Asher et al., 1995; Asher et al., 1998). In this study the main outcomes analysed are ‘ever had asthma’ and ‘wheezing in the last 12 months’ at the age of 5 and 7 years.

At each interview mothers were also asked whether their child was taking any medication (pills, syrups or other liquids, inhalers, patches, creams, suppositories or injections) prescribed by a doctor or hospital on a regular basis (every day for two weeks or more), and if so what was the name of the medication. We describe the prevalence of asthma medications, identified from the British National Formulary codes. Since these children were taking a daily dose it is likely that this reflects a maintenance dose of inhaled corticosteroids, and therefore reflects severity of the condition.

Potential confounding factors

The factors which may potentially explain any observed association between conception history and asthma were identified from the literature, which indicated a potential association with both the outcome and the exposure. These included the following.

Age and sex of cohort member

Known risk factors: mother's history of asthma—reflecting a possible genetic component in the development of asthma in the child, and also a possible link between maternal asthma and fertility owing to shared metabolic roots (Real et al., 2007) or effects of anti-asthmatic medication on fertility (Kallen and Olausson, 2007); mother's BMI (because of link between maternal pre-pregnancy BMI and childhood asthma (Reichman and Nepomnyaschy, 2008), and maternal BMI and subfertility (van der Steeg et al., 2008)); parental smoking (coded as mother smoked during pregnancy, parent smoked earlier in childhood, one parent currently smokes, both parents currently smoke); number of siblings in household, type of childcare at the age of 3 years (both to try to capture some exposure to infections); furry pets in household, damp/condensation in the home (potential irritants and allergens); polluted residential area (environmental effects).

Sociodemographic factors: household socioeconomic position (higher of mother/father using UK National Statistics socioeconomic class, four categories); family income; mother's qualifications (National Vocational Qualifications or equivalent groups); mother's age at birth of child; family type (lone parent, cohabiting or married); ethnicity (white, non-white).

Potential mediating factors

Possible mediating factors considered to be on the causal pathway between conception group and childhood asthma included gestational age (in weeks); delivery type (vaginal, instrumental or Caesarean section); breastfeeding (coded as ‘none’, ‘<4 months’, ‘>4 months’, included as there is an evidence of a protective effect).

Statistical analysis

First, we examined the effect of overall subfertility, by combining the untreated subfertile, OI and ART groups and comparing them to the children born after planned pregnancies. Next, we explored whether there were different effects dependent on degrees of infertility or treatment by separating out the untreated subfertile, OI and ART groups and comparing these to the planned pregnancies. Finally, we investigated whether the treatment groups were at a higher risk than the untreated subfertile group, by using children of untreated subfertile couples as the comparison group.

For each of these comparisons, logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (OR) for the three outcomes (asthma, wheezing and medications) adjusting for potential confounding factors. Potential confounders were included if they were statistically significantly associated with the outcome at the 5% level (indicated by a Wald, P < 0.05) after controlling for other factors in the model. A final model, adjusted for gestational age, delivery type and breastfeeding, assessed whether there was any evidence that the effect of conception group on asthma was mediated via these factors.

All analyses took the clustered, stratified study design into account by using the ‘survey commands’ in Stata version 11SE (StataCorp, 2009). All reported estimates are weighted by sampling and non-response weights to account for missing data owing to non-response at later sweeps (Hansen, 2008; Plewis, 2007).

Results

Description of study population

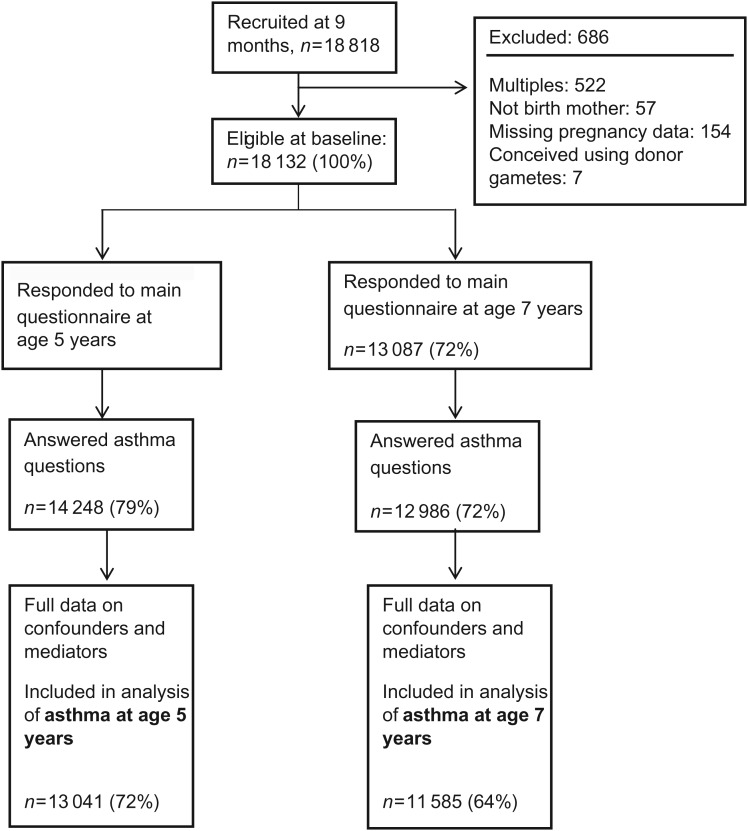

Figure 1 shows the study population, with details of exclusions and non-response. 42% (5684/13 041) of children were born after an unplanned pregnancy; 15% of mothers reported that they felt unhappy or ambivalent about the pregnancy (‘unplanned’ n = 2039), while 27% of mothers were happy (‘mistimed’ n = 3645). 52% of mothers (6575/13 041) reported a planned pregnancy, conceived in <12 months (‘planned group’), a further 4% (505) conceived after 12 months or longer (untreated ‘subfertile group’), while 1.4% (173) had ovulation inducing drugs and 0.9% (104) were born following ART (Table I).

Figure 1.

Flowchart to show study population, including response as a percentage of those eligible at baseline.

Table I.

Description of the study population from the UK Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) at 5-year survey (n = 13 041).

| Reported asthma |

Conception group |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Unplanned | Mistimed | Planned | Subfertile | OI | ART | |

| Unweighted n (wt%) | 1956 (14.7) | 11 085 (85.3) | 2039 (15.3) | 3645 (26.7) | 6575 (51.8) | 505 (4.0) | 173 (1.4) | 104 (0.9) |

| Socio-demographic factors | ||||||||

| Mother's age at birth of cohort member (years) | 29.1 | 27.8 | 26.6 | 27.5 | 29.9 | 31.5 | 31.7 | 33.6 |

| Socioeconomic position, Prof/mgt (wt%) | 29.7 | 40.6 | 20.9 | 28.6 | 48.3 | 48.1 | 51.7 | 57.5 |

| Maternal education, NVQ 4/5 (wt%) | 30.7 | 38.1 | 22.0 | 28.5 | 44.8 | 41.9 | 51.2 | 48.4 |

| Highest household income band ≥£52 000 (wt%) | 9.7 | 16.5 | 7.3 | 10.1 | 20.2 | 17.4 | 28.2 | 21.6 |

| Single parent families (wt%) | 24.2 | 16.8 | 36.1 | 24.4 | 10.2 | 9.8 | 7.1 | 8.9 |

| Ethnicity (non-white) (wt%) | 11.4 | 12.4 | 13.0 | 14.9 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 5.2 | 13.6 |

| Possible risk factors | ||||||||

| Male child (wt%) | 69.4 | 49.6 | 50.1 | 50.1 | 51.4 | 48.9 | 49.2 | 46.2 |

| Mother's history of asthma (wt%) | 28.7 | 14.9 | 18.5 | 18.6 | 16.0 | 13.9 | 15.0 | 6.8 |

| Mother's pre-pregnancy BMI >30 kg/m2 (obese) | 10.8 | 8.7 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 8.5 | 13.6 | 20.0 | 3.0 |

| One or both parents currently smoke (wt%) | 21.8 | 20.7 | 22.7 | 24.0 | 18.3 | 26.4 | 17.1 | 21.5 |

| No siblings in household (wt%) | 18.4 | 15.7 | 20.7 | 20.5 | 11.5 | 20.2 | 20.9 | 48.0 |

| Attended formal childcare (wt%)a | 26.2 | 29.5 | 22.9 | 23.7 | 33.0 | 30.4 | 38.9 | 33.6 |

| Furry pets in household (wt%) | 46.2 | 42.9 | 45.2 | 43.4 | 42.6 | 48.5 | 41.8 | 37.3 |

| House has damp problem (wt%) | 9.2 | 6.6 | 9.6 | 8.8 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 2.5 | 1.7 |

| Residential area considered polluted (wt%)b | 6.8 | 5.5 | 8.8 | 6.6 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 6.9 | 7.6 |

| Potential mediating factors | ||||||||

| Caesarean delivery (wt%) | 22.6 | 20.9 | 16.7 | 20.2 | 21.5 | 32.0 | 34.7 | 40.3 |

| Birthweight (kg, mean) | 3.29 | 3.39 | 3.33 | 3.34 | 3.43 | 3.33 | 3.32 | 3.16 |

| Gestational age (weeks, mean) | 38.9 | 39.9 | 39.1 | 39.1 | 39.3 | 39.2 | 39.0 | 38.2 |

| Preterm birth (<37 weeks gestation) | 10.3 | 6.4 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 5.9 | 7.9 | 12.3 | 18.5 |

| Breastfeeding ≥4 months (wt%) | 25.3 | 35.0 | 21.2 | 29.2 | 39.2 | 32.1 | 39.0 | 44.7 |

NVQ 4/5, National Vocational Qualifications level 4/5 are equivalent to certificates of Higher education and above. Prof/mgt, professional/management; OI, ovulation induction; ART, assisted reproduction technologies. wt% indicates percentages weighted for effects of sampling and non-response.

aAt 3 years.

bParents reported that residential area has problems with pollution, grime, environmental problems—only available at 9 months.

Table I shows clear and consistent differences across the conception groups in terms of demographic, socioeconomic and behavioural factors. Children born after ART were, on average, born at an earlier gestation and lower birthweight than the children from other groups, and were more likely to experience a Caesarean delivery (all P-values < 0.001 for the ART group compared with the normal TTC group). Compared with the planned, fertile group, the unplanned children were generally born to younger mothers, who were less likely to be in a relationship, had lower educational attainment and a more disadvantaged socioeconomic position. Mothers in the unplanned groups were also more likely to smoke in pregnancy, less likely to breastfeed and more likely to report damp housing or polluted residential areas (all P-values < 0.001 for the unplanned group compared with the normal TTC group).

Approximately 15% of the study population had asthma at ages of 5 and 7 years (the prevalence of asthma and related symptoms is shown in Table II). Wheezing in the last year was more prevalent in the younger age group (16 versus 12% at ages of 5 and 7 years). Table 1 shows many of the expected differences in key risk factors between children with and without a doctor diagnosis of asthma. Boys are more likely to be asthmatic than girls (17 versus 12%). Children with asthma are more likely to have a family history of asthma, to be born to less wealthy and less well-educated parents, to be born earlier and at a lower birthweight and were less likely to be breastfed than the children without asthma.

Table II.

Prevalence of asthma and related symptoms in the MCS cohort (wt %, using appropriate weights for each sweep).

| Asthma indicator | Conception status |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unplanned | Mistimed | Planned | Subfertile | OI | ART | Total | |

| Unweighted n (asthma)/N | |||||||

| Age 5 years | 372/2039 | 580/3645 | 885/6575 | 83/505 | 18/173 | 18/104 | 1956/13 041 |

| Age 7 years | 347/1827 | 559/3217 | 896/5837 | 83/463 | 23/154 | 18/87 | 1926/11 585 |

| Asthma | |||||||

| Age 5 years | 17.7 | 15.8 | 13.2 | 16.0 | 11.8 | 23.7 | 15.0 |

| Age 7 years | 18.4 | 17.8 | 14.9 | 17.0 | 15.9 | 22.9 | 16.5 |

| Wheezing in the last year | |||||||

| Age 5 years | 18.2 | 16.8 | 14.3 | 16.8 | 13.8 | 22.4 | 15.7 |

| Age 7 years | 12.3 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 13.4 | 7.6 | 17.0 | 11.9 |

| Asthma medicationsa | |||||||

| Age 5 years | 5.0 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 11.8 | 3.8 |

| Age 7 years | 4.8 | 5.4 | 4.0 | 6.1 | 6.1 | 9.2 | 4.7 |

wt% indicates percentages weighted for effects of sampling and non-response.

aThese are prescribed medications (any pills, syrups or other liquids, inhalers, patches, creams, suppositories or injections) taken every day for 2 weeks or more. Parent reported the name of the medication and those used to treat asthma were identified from British National Formulary codes.

Asthma in subfertile and infertility treatment groups

In comparison with the planned group, children born to parents who experienced a prolonged TTC (>12 months) regardless of subsequent fertility treatment were significantly more likely to report asthma [at 5 years, unadjusted OR: 1.28 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.00, 1.42), fully adjusted OR: 1.39 (1.07, 1.80)].

Considered separately, children born after a prolonged TTC but conceived without fertility treatment (untreated subfertile group) showed a small increase in the odds of asthma or wheezing symptoms at both 5 and 7 years, though this did not reach statistical significance at the 5% level [e.g. for asthma OR: 1.34 (0.98, 1.83) and OR: 1.15 (0.84, 1.58) at 5 and 7 years, respectively, see Table III]: they were more likely to be taking anti-asthmatic medications than their planned peers. The children of mothers who underwent OI treatment showed no increase in asthma or wheezing symptoms, though the use of anti-asthmatic medications was again more common. Children born after ART, however, were significantly more likely to have asthma at both 5 and 7 years of age and adjustment for confounding factors strengthened the observed association. A doubling in risk was seen at 5 years [adj OR: 2.65 (1.48, 4.76) and 1.97 (1.10, 3.53) for asthma and wheezing, respectively]; the effect was reduced at 7 years [OR: 1.84 (1.03, 3.28) and OR: 1.50 (0.77, 2.92)]. This group of children born after ART was also considerably more likely to be taking anti-asthmatic medications than the planned, normal TTC group [adj OR: 4.67 (2.20, 9.94) and 2.29 (1.00, 5.24) at 5 and 7 years, respectively].

Table III.

Odds ratios for asthma, wheezing and medications at 5 and 7 years in each conception group, compared with ‘planned, normal TTC’ group.

| Group | Age 5 years |

Age 7 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Adjusted for sex only | Fully adjusted model | n | Adjusted for sex only | Fully adjusted model | |

| Asthma | ||||||

| Unplanned | 2039 | 1.42 (1.20, 1.67) | 1.11(0.94, 1.31) | 1827 | 1.30 (1.09, 1.54) | 0.96 (0.79, 1.16) |

| Mistimed | 3645 | 1.24 (1.08, 1.42) | 1.03(0.89, 1.19) | 3217 | 1.23 (1.07, 1.41) | 0.98 (0.84, 1.15) |

| Planned | 6575 | Comparison group | 5837 | Comparison group | ||

| All Subfertile | 782 | 1.28 (1.00, 1.65) | 1.39 (1.07, 1.80) | 704 | 1.22 (0.95, 1.57) | 1.23 (0.95, 1.59) |

| Untreated | 505 | 1.27 (0.94, 1.72) | 1.34 (0.98, 1.83) | 463 | 1.18 (0.86, 1.60 | 1.15 (0.84, 1.58) |

| OI | 173 | 0.88 (0.53, 1.46) | 0.96 (0.57, 1.61) | 154 | 1.10 (0.68, 1.78) | 1.17 (0.72, 1.90) |

| ART | 104 | 2.10 (1.16, 3.81) | 2.65 (1.48, 4.76) | 87 | 1.73 (0.97, 3.11) | 1.84 (1.03, 3.28) |

| Wheezing in the last year | ||||||

| Unplanned | 2039 | 1.33 (1.15, 1.55) | 1.13 (0.98, 1.30) | 1826 | 1.10 (0.91, 1.34) | 0.95 (0.77, 1.17) |

| Mistimed | 3645 | 1.21 (1.06, 1.38) | 1.08 (0.94, 1.24) | 3217 | 1.12 (0.95, 1.34) | 1.01 (0.84, 1.22) |

| Planned | 6575 | Comparison group | 5837 | Comparison group | ||

| All Subfertile | 782 | 1.23 (0.97, 1.57) | 1.27 (1.00, 1.63) | 704 | 1.15 (0.87, 1.51) | 1.08 (0.82, 1.43) |

| Untreated | 505 | 1.22 (0.93, 1.60) | 1.24 (0.94, 1.63) | 463 | 1.22 (0.88, 1.68) | 1.15 (0.83, 1.60) |

| OI | 173 | 0.97 (0.58, 1.60) | 1.00 (0.61, 1.66) | 154 | 0.66 (0.34, 1.28) | 0.64 (0.33, 1.22) |

| ART | 104 | 1.76 (1.00, 3.12) | 1.97 (1.10, 3.53) | 87 | 1.65 (0.85, 3.20) | 1.50 (0.77, 2.92) |

| Anti-asthmatic medications taken daily | ||||||

| Unplanned | 2039 | 1.59 (1.20, 2.10) | 1.34 (1.02, 1.78) | 1827 | 1.21 (0.92, 1.58) | 1.03 (0.76, 1.39) |

| Mistimed | 3645 | 1.18 (0.92, 1.51) | 1.04 (0.81, 1.34) | 3217 | 1.37 (1.07, 1.76) | 1.21 (0.95, 1.55) |

| Planned | 6575 | Comparison group | 5837 | Comparison group | ||

| All Subfertile | 782 | 1.87 (1.30, 2.70) | 1.90 (1.32, 2.74) | 704 | 1.67 (1.16, 2.42) | 1.63 (1.13, 2.34) |

| Untreated | 505 | 1.51 (0.94, 2.41) | 1.51 (0.94, 2.41) | 463 | 1.56 (1.00, 2.43) | 1.52 (0.97, 2.38) |

| OI | 173 | 1.65 (0.77, 3.51) | 1.65 (0.77, 3.55) | 154 | 1.57 (0.72, 3.44) | 1.57 (0.73, 3.41) |

| ART | 104 | 4.11 (1.96, 8.64) | 4.67 (2.20, 9.94) | 87 | 2.48 (1.05, 5.86) | 2.29 (1.00, 5.24) |

Odds ratios (95% confidence interval) presented for all subfertile, and by subgroup. Fully adjusted models, controlling for effects of confounding factors: Age 5: maternal history of asthma, family smoking, social class, maternal age; Age 7: maternal history of asthma, family smoking, family income, family type, siblings and pets in the home

Italics indicate subgroups within the ‘All subfertile’ category. The comparison group remains the ‘Planned, normal time to conception’ children.

When compared with the children born to untreated subfertile couples, the ART group was significantly more likely to report an asthma diagnosis and asthma medications at 5 years. The effect was smaller at 7 years and no longer statistically significant. There was no evidence of a difference between the untreated subfertile and the OI groups (see Table IV).

Table IV.

Comparing the subfertile groups: odds ratios (95% confidence interval) for asthma, wheezing and medications at 5 and 7 years in each infertility treatment group, compared with the untreated subfertile group.

| Group | Age 5 years |

Age 7 years |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Adjusted for sex only | Fully adjusted model | n | Adjusted for sex only | Fully adjusted model | |

| Asthma | ||||||

| Subfertile, no treatment | 505 | Comparison group | 463 | Comparison group | ||

| OI | 173 | 0.70 (0.39, 1.25) | 0.72 (0.39, 1.32) | 153 | 0.93 (0.52, 1.67) | 1.01 (0.57, 1.81) |

| ART | 104 | 1.65 (0.87, 3.13) | 1.98 (1.06, 3.72) | 87 | 1.48 (0.80, 2.71) | 1.59 (0.88, 2.89) |

| Wheezing in the last year | ||||||

| Subfertile, no treatment | 505 | Comparison group | 463 | Comparison group | ||

| OI | 173 | 0.79 (0.46, 1.37) | 0.81 (0.47, 1.39) | 153 | 0.54 (0.27, 1.08) | 0.55 (0.28, 1.09) |

| ART | 104 | 1.45 (0.81, 2.58) | 1.59 (0.88, 2.87) | 87 | 1.35 (0.64, 2.85) | 1.30 (0.62, 2.75) |

| Anti-asthmatic medications taken daily | ||||||

| Subfertile, no treatment | 505 | Comparison group | 463 | Comparison group | ||

| OI | 170 | 1.09 (0.44, 2.74) | 1.10 (0.43, 2.79) | 153 | 1.01 (0.42, 2.39) | 1.03 (0.44, 2.44) |

| ART | 104 | 2.73 (1.26, 5.94) | 3.10 (1.42, 6.79) | 87 | 1.59 (0.61, 4.12) | 1.50 (0.60, 3.79) |

Fully adjusted models, controlling for effects of confounding factors: Age 5: maternal history of asthma, family smoking, social class, maternal age; Age 7: maternal history of asthma, family smoking, family income, family type, siblings and pets in the home.

Among the potential mediators, gestational age and breastfeeding behaviour were seen to be independently associated with asthma but the effect of including these variables in the models of the association between conception group and asthma was minimal [adjusted OR for asthma in the ART group at 5 years, including gestational age, breastfeeding and Caesarean section in the model: OR: 2.38 (1.34, 4.24)].

Asthma and pregnancy planning

Unadjusted analyses consistently indicate that unplanned children are more likely to have an asthma diagnosis than their planned peers [OR: 1.42 (1.20, 1.67) and OR: 1.30 (1.09, 1.54) at 5 and 7 years, respectively], but this is attenuated when adjusted for confounding factors [OR: 1.11 (0.94, 1.31) and OR: 0.96 (0.79, 1.16)]. A similar pattern is seen for wheezing in the last year at the age of 5 years, but by the age of 7 years there is no evidence of an increase even in the unadjusted analysis. Reported daily use of anti-asthmatic medications in the unplanned group is higher at the age of 5 years than among the planned group, though this is not seen at the age of 7 years.

The pattern is identical for the mistimed group, though the observed effects in the unadjusted analyses are smaller.

Discussion

In this study of 13 000 UK children we found some evidence that subfertility is associated with an increased risk of asthma in subsequent children, and that this effect is greatest among those conceived following ART. This association varies in strength but appears consistently across a number of indicators, including ‘ever had asthma’, ‘wheezing in the last year’ and prescribed asthma medications. While unadjusted results also suggest that unplanned and mistimed children are at greater risk of asthma and wheezing, it is apparent from the adjusted analyses that this is likely to be a result of confounding, particularly by social circumstances.

Asthma in children born to subfertile and infertile couples

The effects of subfertility on asthma in the subsequent children were assessed in two ways. The first compared the children of subfertile couples (who conceived with no treatment, with OI only or following ART) with the children of parents who planned their conception and conceived in less than 12 months. The second compared the different groups of subfertile couples to explore the influence of severity of infertility and the effects of infertility treatment. The overall picture presented by our results is one of an increased risk of asthma in children born after infertility treatment. The existing literature on asthma after ART conception is limited but our findings are consistent with the findings of the larger Scandinavian registry-based studies which found an increase in both asthma medications (Finnstrom et al., 2011; Kallen et al., 2012) and hospitalizations among ART-conceived children (Ericson et al., 2002; Koivurova et al., 2007; Finnstrom et al., 2011). However, this is not always identified (Pinborg et al., 2003; Klemetti et al., 2006). Other observational studies, which have been smaller and clinic based, have not reported any increase in asthma in ART children but these studies suffered from low participation (and thus potential selection bias) and were unable to control for key confounding factors (Cetinkaya et al., 2009; Sicignano et al., 2010).

In the present study we found that in comparison with the planned, normal TTC group the children born to subfertile parents were more likely to suffer from asthma and to be taking anti-asthmatic medications. When the subfertile group was divided up into untreated subfertility, OI and ART it becomes clear that it is the ART group that is at highest risk of asthma. At 5 years ART children were >2.5 times as likely to have asthma as the planned group [adjusted OR: 2.65 (1.48, 4.76)], and twice as likely as the untreated subfertile group [adj OR: 1.98 (1.06,3.72)]. The observed effects are reduced by 7 years of age, though this appears to be a result of increases in asthma prevalence in the comparison group between 5 and 7 years, rather than a reduction in the ART group, perhaps suggesting earlier diagnosis in the ART children.

A larger Swedish study has indicated that once duration of unwanted childlessness is accounted for, there is little effect of infertility treatment on patterns of asthma (measured by prescribed asthma medications) (Kallen et al., 2012). The higher risk we observed in the ART group could be related to an increased severity of infertility, or a consequence of the treatment: these data do not allow us to distinguish between the two possibilities. If the risk of asthma in children was associated simply with prolonged infertility you may also expect to see an increase in risk among the OI group, albeit smaller than that experienced by the ART group. This is not seen in our data; however, it should be noted that in this population the OI group appear to be quite different from the other subfertile groups: they have a higher prevalence of obesity [which is associated with anovulation and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)] and on average they are also wealthier, more highly educated and their children are more likely to be in formal childcare by 3 years (perhaps indicating a return of parent(s) to the workforce). They also have a shorter average TTC than the untreated subfertile group (mean: 29.2 months versus 38.3 months), perhaps suggesting that they are not representative of a ‘more infertile’ group but instead represent a more demanding subgroup who actively sought intervention and earlier treatment.

If the observed increase in asthma among ART children is real, one must consider what may be driving this association. One possibility is over-reporting by excessively protective ART parents. Similarly, parents who sought medical help to conceive may be more likely to seek medical help for their child and therefore get a diagnosis of asthma or medication prescribed. However, there is no increase in other atopic conditions in this population [eczema and hayfever (data on request)], suggesting that over-reporting is not a major issue because you might expect to see it across all these relatively common conditions.

Another possibility is that the results are related to residual confounding. Our findings are adjusted for recognized risk factors, and we have tried to account for theories such as the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ (Strachan, 1989; Subbarao et al., 2009) by looking at firstborn status, siblings and childcare type to try to capture some measure of exposure to infections but there could still be an unknown or unmeasured confounder driving the observed association. There are other hypotheses about causal factors which we could not address in this analysis as the data were not available [e.g. supplement use might be higher in women who have had fertility problems, and it has been suggested that folate supplementation in pregnancy can result in poorer respiratory outcomes in young children (Whitrow et al., 2009)].

Asthmatic women are more likely to report prolonged childlessness (Kallen and Olausson, 2007), though there is little evidence that this affects the eventual number of pregnancies or live births (Forastiere et al., 2005; Tata et al., 2007). Oligomennorhea (common in PCOS) has been found to be associated with both asthma and lung function, and a shared aetiology (such as insulin resistance) has been hypothesized (Real et al., 2007). It has also been reported that a greater than expected proportion of women undergoing IVF report the use of antiasthmatics (Kallen and Olausson, 2007), and that these medications are associated with annovulatory infertility (Svanes et al., 2005). Asthma has a genetic component (Subbarao et al., 2009), so it may be that higher asthma in subfertile women would lead to higher asthma prevalence in their children. We controlled for maternal asthma and the effects persist; among the children for whom we had data on paternal asthma, controlling for this made little difference (data on request).

Finally, we must consider that the observed association could be causal but we cannot as yet explain the mechanism. Further investigation is needed to disentangle the relative effects of prolonged subfertility and its treatment on asthma in the children.

Asthma in children born after unplanned and mistimed pregnancies

Though the unadjusted analyses suggest that unplanned and mistimed children are more likely to be asthmatic, it is clear from the adjusted analyses that it is differences in social circumstances that explain most of the association. There is a well-recognized socioeconomic gradient in childhood asthma (Subbarao et al., 2009), and this is reflected in our results.

At the age of 5 years, the parents of the unplanned pregnancy group report higher use of anti-asthmatic medication, an effect which persists after adjustment for confounding.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the only observational study of conception status and childhood asthma in a UK population. However, the sample included only 104 singletons born after ART, which precluded analysis by type of infertility treatment (IVF, ICSI). The relatively small ART sample also demands that findings should be interpreted with caution.

We were able to use a validated outcome measure (ISAAC questions), not just hospitalization or medication records. The use of anti-asthmatic medications may be considered a more stringent outcome definition, identifying only the most serious cases; in the MCS only children taking daily medications in the last 2 weeks are identified. It should also be noted that asthma medications may be prescribed more to the children with the most concerned and health-conscious parents and that this may therefore be higher in the ART group (Cardol et al., 2005; Zuidgeest et al., 2009).

The MCS is designed to provide a representative sample of the UK population; however, missing data owing to loss to follow-up can result in bias in cohort studies. Response was socially patterned and non-response weights, which take into account factors such as socioeconomic position, were used in the analysis to minimize the effects. This data set included data on the most important potential explanatory factors, so unlike previous studies we were able to control for many key confounding factors; however, there remains a possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured or unknown risk factors. Although we attempted to examine the effects of possible mediating variables, the data did not allow the exploration of possible causal pathways. Detailed data on conception history also provided the opportunity to examine the effect of a full range of conception histories, rather than simply comparing ART conceptions to all other children.

The prevalence of asthma in our population (15%) is lower than estimates for prevalence in children in the UK in the 1990s from either ISAAC [23% in 1864 6–7 year olds in Sunderland (1998)] or the Health Survey for England [21% of 2–15 year old children in England (Gupta and Strachan, 2004)]. However, this is consistent with recognized temporal changes in the prevalence and diagnosing of asthma. Since the analysis was restricted to singletons, the findings are only generalizable to the singleton population

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that asthma, wheezing and the use of anti-asthmatic medications are higher among children born to subfertile couples than those who conceived in less than 12 months. This is most apparent at the age of 5 years, and remains evident at 7 years, though the size of the effect is diminished. Children born after ART have a much higher risk, though we cannot determine if this is indicative of a treatment effect or related to a greater degree of subfertility in this group of parents. If the observed association is causal, then the mechanism driving it remains unknown and further research in this area is warranted.

Authors' roles

M.Q. is the principal investigator for this project. All authors were involved in the design of the study and the interpretation of findings. C.C. completed the analysis and the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing of the final document. C.C. acts as a guarantor.

Funding

This project was funded by a grant from the Medical Research Council, awarded to M.A.Q., J.J.K., M.R., Y.K. and A.S. and based at the NPEU, University of Oxford. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the children and their families who participate in the MCS.

References

- Asher MI, Keil U, Anderson HR, Beasley R, Crane J, Martinez F, Mitchell EA, Pearce N, Sibbald B, Stewart AW, et al. International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC)—rationale and methods. Eur Respir J. 1995;8:483–491. doi: 10.1183/09031936.95.08030483. doi:10.1183/09031936.95.08030483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher MI, Stewart AW On Behalf of the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Worldwide variations in the prevalence of asthma symptoms: the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Eur Respir J. 1998;12:315–335. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020315. doi:10.1183/09031936.98.12020315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardol M, Groenewegen PP, de Bakker DH, Spreeuwenberg P, van Dijk L, van den Bosch W. Shared help seeking behaviour within families: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:882. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38411.378229.E0. doi:10.1136/bmj.38411.378229.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cetinkaya F, Gelen SA, Kervancioglu E, Oral E. Prevalence of asthma and other allergic diseases in children born after in vitro fertilisation. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2009;37:11–13. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0546(09)70245-9. doi:10.1016/S0301-0546(09)70245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericson A, Nygren KG, Olausson PO, Kallen B. Hospital care utilization of infants born after IVF. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:929–932. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.4.929. doi:10.1093/humrep/17.4.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnstrom O, Kallen B, Lindam A, Nilsson E, Nygren KG, Olausson PO. Maternal and child outcome after in vitro fertilization—a review of 25 years of population-based data from Sweden. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90:494–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01088.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forastiere F, Sunyer J, Farchi S, Corbo G, Pistelli R, Baldacci S, Simoni M, Agabiti N, Perucci CA, Viegi G. Number of offspring and maternal allergy. Allergy. 2005;60:510–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00736.x. doi:10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00736.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta R, Strachan D. The Health of Children and Young People. London: Office for National Statistics; 2004. Chapter 7: Asthma and allergic diseases. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen K. Millennium Cohort Study First, Second and Third Surveys: A Guide to the Datasets. London: Centre for Longitudinal Studies, Institute of Education, University of London; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kallen B, Olausson PO. Use of anti-asthmatic drugs during pregnancy. 1. Maternal characteristics, pregnancy and delivery complications. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63:363–373. doi: 10.1007/s00228-006-0257-1. doi:10.1007/s00228-006-0257-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallen B, Finnstrom O, Nygren KG, Olausson PO. Asthma in Swedish children concieved by in vitro fertilisation. Arch Dis Child. 2012 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2012-301822. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2012-301822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur B, Anderson HR, Austin J, Burr M, Harkins LS, Strachan DP, Warner JO. Prevalence of asthma symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment in 12–14 year old children across Great Britain (international study of asthma and allergies in childhood, ISAAC UK) BMJ. 1998;316:118–124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7125.118. doi:10.1136/bmj.316.7125.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klemetti R, Sevon T, Gissler M, Hemminki E. Health of children born as a result of in vitro fertilization. Pediatrics. 2006;118:1819–1827. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0735. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivurova S, Hartikainen AL, Gissler M, Hemminki E, Jarvelin MR. Post-neonatal hospitalization and health care costs among IVF children: a 7-year follow-up study. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2136–2141. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem150. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel SP, Jarvelin MR, Little MP. Systematic review of worldwide variations of the prevalence of wheezing symptoms in children. Environ Health. 2008;7:57. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-7-57. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-7-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinborg A, Loft A, Schmidt L, Andersen AN. Morbidity in a Danish national cohort of 472 IVF/ICSI twins, 1132 non-IVF/ICSI twins and 634 IVF/ICSI singletons: health-related and social implications for the children and their families. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1234–1243. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg257. doi:10.1093/humrep/deg257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plewis I. Non-response in a birth cohort study: the case of the millennium cohort study. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2007;10:325–334. doi:10.1080/13645570701676955. [Google Scholar]

- Real FG, Svanes C, Omenaas ER, Anto JM, Plana E, Janson C, Jarvis D, Zemp E, Wjst M, Leynaert B, et al. Menstrual irregularity and asthma and lung function. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:557–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.041. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman NE, Nepomnyaschy L. Maternal pre-pregnancy obesity and diagnosis of asthma in offspring at age 3 years. Matern Child Health J. 2008;12:725–733. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0292-2. doi:10.1007/s10995-007-0292-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennhauser FH, Braun-Fahrlander C, Wildhaber JH. The burden of asthma in children: a European perspective. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2005;6:2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2004.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sicignano N, Beydoun HA, Russell H, Jones H, Jr, Oehninger S. A descriptive study of asthma in young adults conceived by IVF. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010;21:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.07.009. doi:10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CA, Turner D, Kuehni CE, Couriel JM, Silverman M. The economic impact of preschool asthma and wheeze. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:1000–1006. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00057002. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00057002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299:1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. doi:10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao P, Mandhane PJ, Sears MR. Asthma: epidemiology, etiology and risk factors. CMAJ. 2009;181:E181–E190. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080612. doi:10.1503/cmaj.080612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svanes C, Real FG, Gislason T, Jansson C, Jogi R, Norrman E, Nystrom L, Toren K, Omenaas E. Association of asthma and hay fever with irregular menstruation. Thorax. 2005;60:445–450. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.032615. doi:10.1136/thx.2004.032615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tata LJ, Hubbard RB, McKeever TM, Smith CJ, Doyle P, Smeeth L, West J, Lewis SA. Fertility rates in women with asthma, eczema, and hay fever: a general population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1023–1030. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk092. doi:10.1093/aje/kwk092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Steeg JW, Steures P, Eijkemans MJ, Habbema JD, Hompes PG, Burggraaff JM, Oosterhuis GJ, Bossuyt PM, van der Veen F, Mol BW. Obesity affects spontaneous pregnancy chances in subfertile, ovulatory women. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:324–328. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem371. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitrow MJ, Moore VM, Rumbold AR, Davies MJ. Effect of supplemental folic acid in pregnancy on childhood asthma: a prospective birth cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170:1486–1493. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp315. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuidgeest MG, van Dijk L, Spreeuwenberg P, Smit HA, Brunekreef B, Arets HG, Bracke M, Leufkens HG. What drives prescribing of asthma medication to children? A multilevel population-based study. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7:32–40. doi: 10.1370/afm.910. doi:10.1370/afm.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]