The authors conclude that the inpatient oncology service predominantly cares for a population nearing the end of life; therefore, goals should include symptom control and end-of-life planning.

Abstract

Introduction:

Despite advances in the care of patients with cancer over the last 10 years, cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States. Many patients receive aggressive, in-hospital end-of-life care at high cost. There are few data on outcomes after unplanned hospitalization of patients with metastatic cancer.

Methods:

In 2000 and 2010, data were collected on admissions, interventions, and survival for patients admitted to an academic inpatient medical oncology service.

Results:

The 2000 survey included 191 admissions of 151 unique patients. The 2010 survey assessed 149 admissions of 119 patients. Lung, GI, and breast cancers were the most common cancer diagnoses. In the 2010 assessment, pain was the most common chief complaint, accounting for 28%. Although symptoms were the dominant reason for admission in 2010, procedures and imaging were common in both surveys. The median survival of patients after discharge was 4.7 months in 2000 and 3.4 months in 2010. Despite poor survival in this patient population, hospice was recommended in only 23% and 24% of patients in 2000 and 2010, respectively. Seventy percent of patients were discharged home without additional services.

Conclusion:

On the basis of our data, an unscheduled hospitalization for a patient with advanced cancer strongly predicts a median survival of fewer than 6 months. We believe that hospital admission represents an opportunity to commence and/or consolidate appropriate palliative care services and end-of-life care.

Introduction

Over the past 10 years, there have been multiple advances in cancer care. Although chemotherapy options and supportive care for patients with advanced cancer have evolved, cancer remains the second leading cause of death in the United States.1 It is estimated that 571,950 people will die this year as a result of cancer in the United States.2 Patients with end-stage cancer have high rates of hospitalization, with over 60% being admitted in the last month of life.3 The use of aggressive end-of-life care is often discordant with the desires of the general population.4–6 The cost of cancer care is rising at a dramatic rate, with a high proportion of dollars being spent on end-of-life-care.7

In patients with cancer who receive inpatient palliative care consultation, the median survival after consultation ranges from 4 to 30 days.8–10 This population is heavily selected to have a poor prognosis. Few data exist on the estimated survival of patients with advanced cancer after unplanned hospitalization. As part of a quality improvement project in 2000, the inpatient oncology service at an academic medical center was evaluated for patient characteristics, interventions, and survival. In 2010, this assessment was repeated with additional emphasis on reason for admission, disposition, services at discharge, and hospice recommendations. We aimed to compare the outcomes and interventions over time as well as to provide recommendations for future improvement in services directed toward this population.

Methods

2000 Survey

Study population.

All patients admitted to the University of Wisconsin (UW) Hospital inpatient oncology service from August 1, 2000, through December 31, 2000, were included. At that time, the inpatient oncology service admitted patients with solid tumors, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and multiple myeloma.

Study design.

Data were collected retrospectively on consecutive patients as part of a quality improvement project. Patient characteristics assessed included age, sex, site of primary cancer diagnosis, and stage (metastatic/advanced or local). During hospitalization, the number and type of imaging studies, procedures, and antitumor interventions as well as length of stay and whether the admission was a repeat admission were collected. Overall survival was assessed at 1 year using the Wisconsin death registry.

2010 Survey

Study population.

All patients with an unplanned admission to the UW Hospital inpatient oncology service from August 31, 2010, through December 23, 2010, were included, regardless of disease stage. An admission was considered unplanned if patients were admitted for symptoms or additional work-up that could not be completed as an outpatient. Patients who had previously planned admissions for procedures or chemotherapy were excluded from this analysis, because they received care through another nurse practitioner–run service. This population included only patients with solid tumors. Patients with hematologic malignancies were cared for through a separate service.

Study design.

As part of a quality improvement project, data were collected prospectively, including age, site of primary cancer, reason for admission, whether the admission was a repeat admission, evidence of disease progression, procedures, consults, and imaging performed, discharge diagnosis, disposition, hospice recommendation, length of stay, and disposition. The date of death was collected using hospital records and the UW Carbone Cancer Center tumor registry.

Results

The 2000 and 2010 surveys were similar in patient demographics, interventions, and outcomes (Table 1). The 2000 survey included 191 admissions of 151 unique patients. The mean age was 60 years (range, 27 to 88 years). Of these patients, 19 (13%) had localized disease, and 132 (87%) had metastatic disease. During the 2010 data collection, there were 149 admissions of 119 unique patients. In both 2000 and 2010, lung, GI, and breast cancers were the most common underlying cancer diagnoses. The median length of stay was similar in both surveys, at 3 days (range, 1 to 36 days) in 2000 and 4 days (range, 1 to 36 days) in 2010.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographics, Interventions, and Outcomes in 2000 and 2010 Surveys

| Demographic/Intervention/Outcome | 2000 | 2010 |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | 151 | 149 |

| Admissions, No. | 191 | 119 |

| Cancer type, No. | ||

| GI | 38 | 31 |

| Lung | 33 | 23 |

| Breast | 24 | 16 |

| Genitourinary | 25 | 13 |

| Head and neck | 5 | 9 |

| Other | 26 | 27 |

| Length of stay, days | ||

| Median | 3 | 4 |

| Range | 1-36 | 1-36 |

| Imaging studies, No. | 196 | 415 |

| Procedures, No. | 186 | 82 |

| Chemotherapy, No. | 29 | 5 |

| Hospice recommended, % | 24 | 23 |

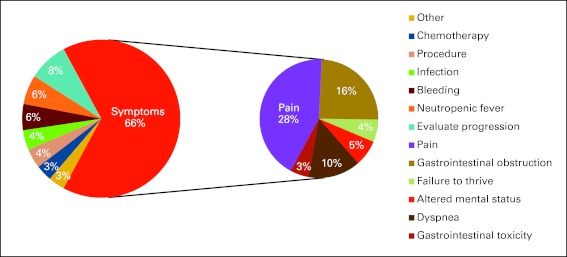

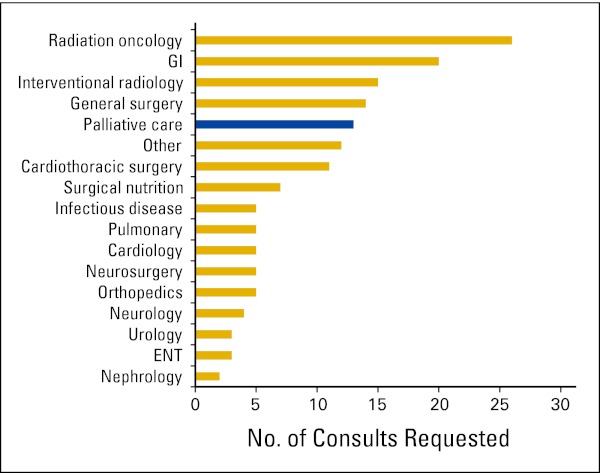

A majority of patients were admitted for uncontrolled symptoms in both 2000 and 2010 (70% and 66%). Although relatively few patients were admitted solely for procedures or chemotherapy in either analysis, the number of admissions for chemotherapy decreased from 11% in the 2000 assessment to 3% in 2010. In the 2010 survey, pain was the most common chief complaint at admission (28%; Fig 1). Although symptoms were the dominant reason for admission, procedures and imaging were common in both surveys. The number of procedures performed among inpatients decreased, with 186 procedures performed in 2000 and 82 in 2010. In contrast, the frequency of imaging increased, with 196 versus 415 studies. These imaging studies predominantly were x-rays, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography scans, and ultrasounds. In terms of cancer-directed therapy, 29 patients received chemotherapy in 2000 compared with five patients in 2010. The 2000 review did not include assessment of consultation, but in 2010, the most common reason for consultation was for radiation therapy. Despite the majority of patients being admitted for uncontrolled symptoms, palliative care consultation was only the fifth most common consult, behind the procedural-based specialties of radiation oncology, gastroenterology, interventional radiology, and general surgery (Appendix Fig A1, online only).

Figure 1.

Chief reasons for admission to the inpatient oncology service.

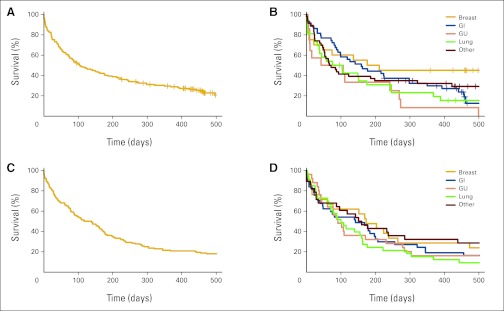

In 2010, when patients were assessed for progression, 85% had progression, 7% were unchanged, and 8% had improvement in disease burden. The median survival of patients after discharge in 2000 was 4.7 months. At 1 year, 73.5% of patients had died. In 2010, the median survival after discharge was 3.4 months, with 74.8% of patients deceased at 1 year. The short survival outcomes were consistent across disease types in both 2000 and 2010 (Fig 2).

Figure 2.

(A) Overall survival and (B) survival by disease type of patients in 2010 survey. (C) Overall survival and (D) survival by disease type in 2000. GU, genitourinary.

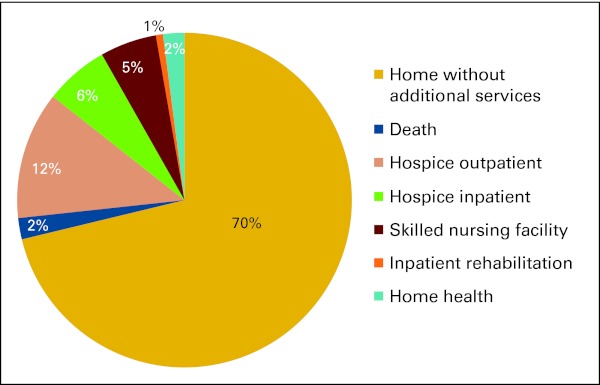

Within this highly symptomatic population of patients from 2010, 70% were discharged home without additional services. Only 18% of patients were enrolled in hospice at discharge. Of these patients, 12% received outpatient hospice, and 6% received inpatient hospice care (Appendix Fig A2, online only). Despite the high rate of death within 6 months, the inpatient teams only recommended hospice during 24% (2000) and 23% (2010) of admissions.

Discussion

From the initial 2000 survey, we concluded that the inpatient oncology service predominantly cares for a population nearing the end of life; therefore, goals should include symptom control and end-of-life planning. We found that despite 10 years of time, this message remains accurate. Admission rates remain steady, and patient demographics are similar. The proportion of patients with the five most common disease sites (GI, lung, breast, genitourinary, and head and neck) was similar in the outpatient and inpatient settings. From 2000 to 2010, there were 4,915 unique patients with metastatic cancer seen for an initial visit at the UW Carbone Cancer Center in the five most common disease sites (GI, lung, breast, genitourinary, and head and neck). The number of new metastatic patients increased modestly, with 379 new patients in this group in 2000 compared with 424 patients in 2010.

Given the declining rates of procedures and chemotherapy administered, we postulate that in 2000, patients were more often receiving active workup and cancer therapies as inpatients. In 2010, we believe that a greater amount of workup, procedures, and chemotherapy were performed in the outpatient setting, and therefore, pain crisis was the most common chief complaint. The high symptom burden of the 2010 population suggests a sicker population of patients.

On the basis of our data from 2000 and 2010, an unscheduled hospitalization for someone with advanced cancer strongly predicts survival of fewer than 6 months (median, 3.4 months in 2010 and 4.7 months in 2000). Although the prognosis for patients with metastatic cancer varies widely based on the primary site, patients who are hospitalized have a poor prognosis regardless of cancer type. Patients with good performance status who have changes in symptoms often can be managed as outpatients, whereas patients with global decline require admission. Therefore, hospital admission can be used as a marker for death in the near term. Given the overall poor survival, any patient with metastatic cancer with an unscheduled hospitalization could be considered hospice eligible and appropriate for end-of life planning, including discussion of advanced directives. Palliative care consultation would be a potential intervention to better address end-of-life care for these patients.

In this population, palliative care consultation was only performed during 6.8% of admissions in 2010. We suspect that this is in part the result of the assumption that end-of-life conversations can be performed well by the attending oncologist. However, despite this sentiment, hospice was only recommended during 23% and 24% of admissions in 2000 and 2010, respectively. When reviewing these data with our inpatient oncologists, some noted that they were more comfortable with the decision to pursue hospice being made between the patient and primary outpatient oncologist, who should have a better relationship with the patient. We believe that this represents a missed opportunity to provide supportive palliative care services and end-of-life care. Recent data have emerged showing the benefit of early palliative care involvement. In non–small-cell lung cancer, Temel et al11 demonstrated improvement in quality of life as well as a survival benefit with comanagement of oncology and palliative care physicians. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines recommend that palliative care be integrated into the management of all patients with metastatic cancer.12 The best approach for palliative care involvement remains unclear. Although early integration into the clinic setting would be ideal, there exists a shortage of palliative care physicians and infrastructure.13 Providing inpatient palliative care consultation would allow for delivery of service to patients who are truly approaching the end of life and likely to have high need of supportive care.

UW established an inpatient palliative care consult team in 1996. This team now consists of a palliative care physician, nurse practitioner, social worker, chaplain, and pharmacist. They can provide multidisciplinary care for patients admitted to an inpatient palliative care unit as well as consultation at physician request. In response to this assessment, we have implemented automatic palliative care consultation for all inpatients in our solid tumor oncology service. We hope to extend the involvement of palliative care into the outpatient setting in the near future. Although we hope for a future where all patients, inpatient and outpatient, will be able to benefit from palliative care services, we believe that inpatient palliative care consultation is an important component of quality cancer care.

Acknowledgment

We thank Robert Millholland and the University of Wisconsin Tumor Registry for assistance with this project.

Appendix

Figure A1.

Consultations requested by primary team in 2010 survey. ENT, ear nose throat.

Figure A2.

Percentages of patients who received supportive services at discharge.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Gabrielle B. Rocque, Anne E. Barnett, Lisa C. Illig, Howard H. Bailey, Toby C. Campbell, James A. Stewart, James F. Cleary

Collection and assembly of data: Gabrielle B. Rocque, Anne E. Barnett, Lisa C. Illig

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Kochanek KD, Xu JQ, Murphy SL, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports. Deaths: Preliminary Data for 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr59/nvsr59_04.pdf. [PubMed]

- 2.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2011. http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/cancerfactsfigures/cancer-facts-figures-2011.

- 3.Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care. End-of-Life Care. http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/data/table.aspx?ind=178.

- 4.Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ. Place of care in advanced cancer: A qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:287–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beccaro M, Costantini M, Giorgi Rossi P, et al. Actual and preferred place of death of cancer patients. Results from the Italian Survey of the Dying of Cancer (ISDOC) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:412–416. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somogyi-Zalud E, Zhong Z, Hamel MB, et al. The use of life-sustaining treatments in hospitalized persons aged 80 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:930–934. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith TJ, Hillner BE. Bending the cost curve in cancer care. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2060–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1013826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: A randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendaly EA, Groves J, Juliar B, et al. Financial impact of palliative care consultation in a public hospital. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1304–1308. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamal AH, Swetz KM, Carey EC, et al. Palliative care consultations in patients with cancer: A Mayo Clinic 5-year review. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:48–53. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: The integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:880–887. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.5161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lupu D. Estimate of current hospice and palliative medicine physician workforce shortage. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]