Abstract

The role of placental growth factor (PlGF) in modulation of tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth remains an enigma. Furthermore, anti-PlGF therapy in tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth remains controversial in preclinical tumor models. Here we show that in both human and mouse tumors, PlGF induced the formation of dilated and normalized vascular networks that were hypersensitive to anti-VEGF and anti–VEGFR-2 therapy, leading to dormancy of a substantial number of avascular tumors. Loss-of-function using plgf shRNA in a human choriocarcinoma significantly accelerated tumor growth rates and acquired resistance to anti-VEGF drugs, whereas gain-of-function of PlGF in a mouse tumor increased anti-VEGF sensitivity. Further, we show that VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-1 blocking antibodies displayed opposing effects on tumor angiogenesis. VEGFR-1 blockade and genetic deletion of the tyrosine kinase domain of VEGFR-1 resulted in enhanced tumor angiogenesis. These findings demonstrate that tumor-derived PlGF negatively modulates tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth and may potentially serve as a predictive marker of anti-VEGF cancer therapy.

Keywords: antiangiogenic therapy, drug resistance, biomarker, tumor microenvironment, tumor neovascularization

Despite improvement of survival in patients with various cancers using antiangiogenic drugs, the overall clinical benefit of these high-cost drugs remains rather modest (1–3). One of the key issues needing improvement in antiangiogenic therapy is to be able to reliably define biomarkers that predict patient responses and circumvent drug resistance. Unfortunately, a reliable predictive biomarker is not available for antiangiogenic drugs in today’s clinical practice.

Placental growth factor (PlGF) was originally discovered by a genetic approach and was defined as an endothelial growth factor based on its sequence homology to VEGF (4). Unlike VEGF, PlGF exclusively binds to VEGF receptor 1 (VEGFR-1), which may function as a decoy receptor in regulation of VEGF-induced angiogenesis (5). In fact, deletion of the vegfr-1 gene in mice led to early embryonic lethality owing to uncontrolled growth of endothelial cells and disorganization of the vascular architecture (6). Although some studies reported that PlGF displays potent endothelial proliferative activity in vitro and angiogenic activity in vivo (4, 7–13), others were unable to describe similar findings (14–18). In concordance with the latter notion, genetic deletion of the plgf gene did not demonstrate any obvious vascular defects, with the exception of certain pathological settings such as ischemia (11). In addition to forming homodimers, PlGF and VEGF can also form heterodimers that exhibit only weak biological activity, suggesting that PlGF may negatively modulate VEGF-induced angiogenesis by formation of biologically inactive heterodimers (15, 16, 19, 20).

Based on its relatively broad distribution in various cell types including inflammatory cells, bone marrow progenitor cells, and even tumor cells, PlGF may regulate inflammation, tumor cell growth, and stromal expansion (21). Thus, the biological effects of PlGF in the tumor environment could be complex and dynamic. In some studies, PlGF was reported to promote tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth (8, 9, 13), whereas several other studies showed that overexpression of PlGF in tumor cells suppresses tumor neovascularization and tumor growth (14–18). Similarly, anti-PlGF–neutralizing antibodies generated from different laboratories were also reported to display opposing effects on tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth (8, 9, 22). However, none of these studies have taken into consideration the cellular source of PlGF in relation to VEGF production, particularly the formation of PlGF–VEGF heterodimers.

Pharmaceutical development of PlGF blockades for cancer therapy has experienced disappointing outcomes. To better understand the complex mechanisms underlying PlGF-regulated angiogenesis and tumor growth and to define PlGF as a therapeutic target, we treated both human and mouse PlGF-expressing tumors with several anti-VEGF and anti–VEGFR-1 or anti–VEGFR-2 agents. Our results demonstrate that tumor-derived PlGF significantly increased antiangiogenic and antitumor sensitivity of anti-VEGF and anti–VEGFR-2 blocking antibodies by a possible mechanism involving PlGF homodimer– or PlGF–VEGF heterodimer–triggered negative signals via VEGFR-1 activation.

Results

Hypersensitivity of a PlGF-Expressing Human Choriocarcinoma to Anti-VEGF Therapy.

PlGF was recently reported to confer anti-VEGF resistance in some mouse tumor models (9). We analyzed a panel of tumors to detect PlGF expression levels. Among the studied tumors including human breast cancer (MDA-MB231 and MCF-7), squamous cell carcinoma (A431), melanoma (UACC-257 and MUM2B), pancreatic carcinoma (PANC1 and PANC10.05), hepatocellular carcinoma (Huh7), ovarian carcinoma (OVCAR8), and choriocarcinoma (JE-3), JE-3 choriocarnoma expressed the highest level of PlGF (Table S1). Consistent with high PlGF expression level, the JE-3 tumor tissue showed a relatively normalized tumor vasculature compared with those in other tumor types (Fig. S1). To investigate anti-VEGF drug sensitivity of PlGF-expressing tumors, we chose a human choriocarcinoma cell line (JE-3) that naturally expresses a high level of PlGF. Measurement of PlGF tumor tissues by a sensitive ELISA showed that JE-3 tumors produced a high level of PlGF homodimers (>63.76 ng/mL) (Table 1). Interestingly, in addition to PlGF homodimers, a substantial amount of PlGF molecules participated in heterodimerization with VEGF, leading to a markedly reduced level of VEGF–VEGF homodimers (Table 1). These findings suggest that VEGF preferably forms heterodimers with PlGF in the JE-3 human tumor.

Table 1.

Measurement of various dimeric forms of VEGF and PlGF in human tumors

| Tumors | hPlGF–hPlGF (ng/mL) | hVEGF–hVEGF (ng/mL) | hPlGF–hVEGF (ng/mL) |

| JE-3 | 63.760 ± 0.170 | 0.379 ± 0.065 | 3.611 ± 0.150 |

| JE-3 control shRNA | 58.313 ± 6.208 | 0.655 ± 0.077 | 2.720 ± 0.157 |

| JE-3 Plgf shRNA | 11.460 ± 1.917 | 0.692 ± 0.078 | 0.865 ± 0.013 |

hPlGF, human PlGF; hVEGF, human VEGF.

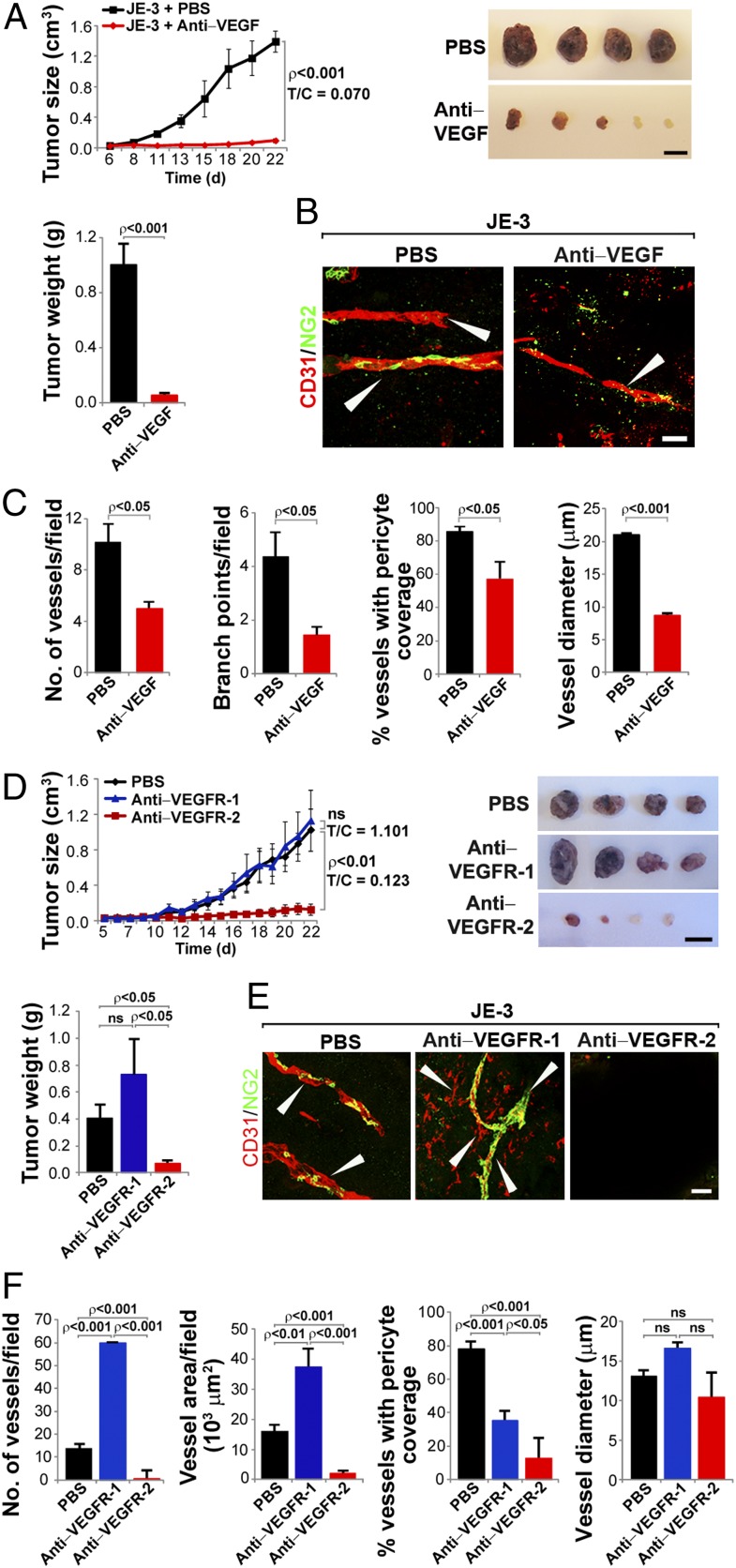

To study whether tumor-derived PlGF contributed to anti-VEGF resistance, JE-3 tumor-bearing mice were treated with a rabbit anti-VEGF neutralizing antibody (VEGF blockade), which blocks both human and mouse tumor VEGF as previously described (23). Unexpectedly, PlGF-expressing JE-3 tumors were highly sensitive to VEGF blockade. At day 22 after treatment, 93% inhibition of tumor growth was achieved, and two of six VEGF blockade–treated tumors remained virtually dormant at the avascular stage without further growth (Fig. 1A). In contrast, vehicle-treated tumors grew at an average size of approximately 1.4 cm3 and weighed about 1 g at this time point (Fig. 1A). Immunofluorescence analysis demonstrated a marked reduction of microvessel density in the VEGF blockade–treated group (Fig. 1 B and C). Additionally, vascular branch points, pericyte coverage, and vessel diameters were all significantly decreased in the VEGF blockade–treated group compared with those in the vehicle-treated group (Fig. 1 B and C). These findings demonstrate that PlGF expression in a naturally occurring human tumor does not confer anti-VEGF resistance. Conversely, the PlGF-expressing tumor was hypersensitive to anti-VEGF treatment, which induced avascular tumor dormancy in two of six tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Hypersensitivity of PlGF-expressing human JE-3 choriocarcinoma to anti-VEGF and anti-VEGFR therapy. (A) Growth rates of vehicle- and VEGF blockade–treated JE-3 tumors. T/C, treatment vs. control. Data show both tumor volumes and tumor weights (6 mice per group). (Scale bar, 1 cm.) (B) Representative micrographs of CD31-positive tumor vessels in vehicle- and VEGF blockade–treated JE-3 tumors. Red, CD31-positive signal; green, NG2-positive signal. Arrowheads point to vessels. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (C) Quantification of microvessel numbers, branch points, pericyte coverage, and vessel diameter in vehicle- and VEGF blockade–treated JE-3 tumors (7–14 samples per group). (D) Growth rates of vehicle-, VEGFR-1 blockade–, and VEGFR-2 blockade–treated JE-3 tumors. Data show both tumor volumes and tumor weights (6 mice per group). ns, not significant. (Scale bar, 1 cm.) (E) Representative micrographs of CD31-positive tumor vessels in vehicle-, VEGFR-1 blockade–, and VEGFR-2 blockade–treated JE-3 tumors. Red, CD31-positive signal; green, NG2-positive signal. Arrowheads point to vessels. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (F) Quantification of microvessel numbers, branch points, pericyte coverage, and vessel diameter in vehicle-, VEGFR-1 blockade–, and VEGFR-2 blockade–treated JE-3 tumors (4–9 samples per group).

Anti–VEGFR-2, but Not Anti–VEGFR-1, Suppresses Angiogenesis and Human Tumor Growth.

PlGF exclusively binds to VEGFR-1 and not VEGFR-2 (5, 24). To delineate the role of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth, JE-3 tumor-bearing mice were treated with an anti-mouse VEGFR-1–neutralizing antibody (hereafter called VEGFR-1 blockade) (25). Surprisingly, VEGFR-1 blockade did not significantly affect tumor growth rate compared with the control group (Fig. 1D). These findings suggest that the PlGF-activated signaling system via the VEGFR-1 system does not significantly contribute to tumor growth. In striking contrast, VEGFR-2 blockade (26) markedly inhibited JE-3 tumor growth (Fig. 1D). At day 19 after treatment, two of six VEGFR-2–treated tumors remained as avascular nodules, whereas VEGFR-1– and vehicle-treated tumors reached a size of 1.2 cm3 (Fig. 1D).

Consistent with tumor growth rates, opposing effects of tumor angiogenesis by VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 blockades were detected (Fig. 1 E and F). Intriguingly, VEGFR-2 blockade virtually completely depleted tumor microvessels, leading to development of a large avascular area in all treated tumors. Only incomplete and scattered tumor microvessels were detectable in one of six VEGFR-2 blockade–treated tumors. In contrast, VEGFR-1 blockade significantly increased blood vessel density in tumors (Fig. 1 E and F). In VEGFR-2 blockade–treated samples, large-diameter vessels typically seen in JE-3 tumors were rarely detectable. Quantification analysis showed that both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 blockades decreased NG2+ pericyte coverage (Fig. 1 E and F).

Silence of PlGF in Human JE-3 Tumors Increases Drug Resistance to VEGFR-2 Blockade.

Given the fact that PlGF-expressing JE-3 tumors were highly sensitive to VEGFR-2 blockade, we focused our subsequent studies on VEGFR-2 blockade. To further study the involvement of PlGF in modulation of the drug sensitivity of anti-VEGF agents, PlGF expression in tumor cells was silenced using specific shRNA targeting the PlGF transcripts. First, we showed that transfection of plgf-shRNA in JE-3 cells did not affect VEGF expression level compared with the scrambled shRNA-transfected cells, suggesting that plgf shRNA was specific for PlGF (Fig. 2C). As expected, an approximately sixfold decrease of PlGF homodimers was detected in plgf shRNA tumors compared with control shRNA–transfected tumors (Table 1). Similarly, the amount of VEGF–PlGF heterodimers was also markedly decreased in plgf shRNA tumors. Transfection of plgf shRNA in JE-3 tumor cells sufficiently inhibited PlGF expression. Quantitative PCR analysis showed that plgf shRNA effectively blocked PlGF synthesis (Fig. 2C). Consistent with altered PlGF expression levels, plgf shRNA–transfected, but not control shRNA–transfected, tumors showed a significantly accelerated growth rate as measured by both tumor volumes and weights (Fig. 2A), validating the fact that PlGF negatively regulates tumor growth.

Fig. 2.

Growth rates, angiogenesis, and responses of plgf shRNA– and control shRNA transduced JE-3 tumors to anti-VEGF therapy. (A) Tumor growth rates and tumor angiogenesis in plgf shRNA and control shRNA transduced JE-3 tumors (6–7 mice per group). In immunohistological panels, CD31-positive signals are presented in red, NG2-positive signals are in green, and tumor cells are in blue. Arrowheads point to vessels. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (B) Tumor growth rates, tumor weights, and morphology of vehicle- and VEGFR-2–treated plgf shRNA– and control shRNA–transduced JE-3 tumors (5–8 mice per group). Dashed lines compare T/C of the treated and nontreated groups when tumor sizes are equal in PlGF and control tumors. (Scale bar, 1 cm.) (C) Quantitative PCR analysis of plgf and vegf mRNA levels in plgf shRNA– and control shRNA–transduced JE-3 tumor cells (3 samples per group). (D) Representative micrographs of CD31-positive tumor vessels in vehicle- and VEGFR-2 blockade–treated plgf shRNA and control shRNA JE-3 tumors. Red, CD31-positive signal; green, NG2-positive signal. Arrowheads point to vessels. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (E) Quantification of microvessel numbers, branch points, pericyte coverage, and vessel diameter in vehicle- and VEGFR-2 blockade–treated plgf shRNA and control shRNA JE-3 tumors (6–16 samples per group).

Consistent with altered tumor growth rates, plgf shRNA–transfected tumors exhibited a marked increase of vascular density compared with the scrambled shRNA–transfected control tumors (Fig. 2 A, D, and E). Additionally, microvessels in plgf shRNA–transfected JE-3 tumors appeared to have more disorganized and premature vascular networks compared with the scrambled shRNA–transfected control tumors (Fig. 2A). These findings demonstrate that inhibition of PlGF synthesis in JE-3 tumor cells by shRNA significantly augments tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth. We next treated plgf shRNA–transfected and scrambled shRNA–transfected JE-3 tumors with VEGFR-2 blockade. Interestingly, suppression of PlGF production by plgf shRNA led to a significant increase of resistance to VEGFR-2 blockade treatment (Fig. 2B). Similarly, the tumor vasculature with loss of function by knocking down PlGF might gain resistance to anti–VEGFR-2 treatment (Fig. 2 D and E). Our results show that JE-3 tumor cell–derived PlGF is responsible for the drug hypersensitivity of antiangiogenic agents that target the VEGFR-2 signaling system.

Expression of PlGF in a Murine Fibrosarcoma Increases Antitumor Sensitivity of VEGF Blockade.

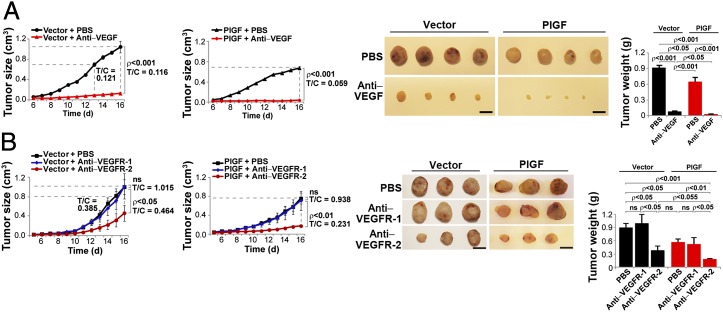

To validate our findings, we established a murine stable PlGF-expressing T241 fibrosarcoma with human plgf-1 cDNA as previously described (14, 16). Expression levels of various VEGF and PlGF dimers were analyzed (Table 2). As expected, PlGF T241 tumors grew significantly slower relative to vector T241 tumors (Fig. 3A). To exclude the possibility that PlGF might have a direct effect on tumor cells, we measured mRNA expression levels of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 in T241 tumor cells. Expectedly, T241 tumor cells lacked a detectable level of VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 expression compared with a murine endothelial cell line (27) (Figs. S2 and S3). Consistent with the undetectable levels of VEGF receptors, treatment of T241 cells with PlGF or VEGF did not alter cell proliferation (Fig. S3). Similarly, expression of PlGF or VEGF in these cells did not affect cell proliferation (Fig. S3). These findings demonstrate that extrogenously added or endogenously expressed PlGF and VEGF do not affect tumor cell growth. Consistent with the JE-3 choriocarcinoma results, expression of PlGF in T241 fibrosarcoma significantly increased the antitumor activity of VEGF blockade (Fig. 3A). Markedly, VEGF blockade–treated PlGF T241 tumors were at very small sizes at day 16 after treatment (Fig. 3A). Gross examination of the dissected tumors showed that VEGF blockade–treated PlGF T241 tumors appeared pale and lacked obvious blood supply (Fig. 3A). These findings were also validated in PlGF-2 T241 fibrosarcoma (Fig. S4).

Table 2.

Measurement of various dimeric forms of VEGF and PlGF in mouse tumors

| Tumors | hPlGF–hPlGF (ng/mL) | mVEGF–mVEGF (ng/mL) | hPlGF–mVEGF(ng/mL) |

| Vector T241 | ND | 1.125 ± 0.001 | ND |

| PlGF T241 | 15.274 ± 0.114 | 0.461 ± 0.005 | 4.155 ± 0.003 |

hPlGF, human PlGF; mVEGF, mouse VEGF; ND, not detectable.

Fig. 3.

PlGF-expressing mouse tumors in response to anti-VEGF therapy. (A) Growth rates, tumor weights, and morphology of vehicle- or VEGF blockade–treated vector T241 and PlGF T241 tumor-bearing fibrosarcomas (6 mice per group). (Scale bar, 1 cm.) (B) Growth rates, tumor weights, and morphology of vehicle-, VEGFR-1 blockade–, or VEGFR-2 blockade–treated vector T241 and PlGF T241 tumor-bearing fibrosarcomas (5–11 mice per group). Dashed lines compare T/C of the treated and nontreated groups when tumor sizes are equal in PlGF and control tumors. (Scale bar, 1 cm.)

Similar to VEGF blockade, treatment of PlGF T241 tumor-bearing mice with VEGFR-2 blockade resulted in a significantly greater suppressive effect of tumor growth compared with vector T241 tumors (Fig. 3B). In striking contrast to VEGFR-2 blockade, VEGFR-1 blockade did not significantly affect tumor growth in both PlGF T241 and vector T241 tumors relative to their respective vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 3B).

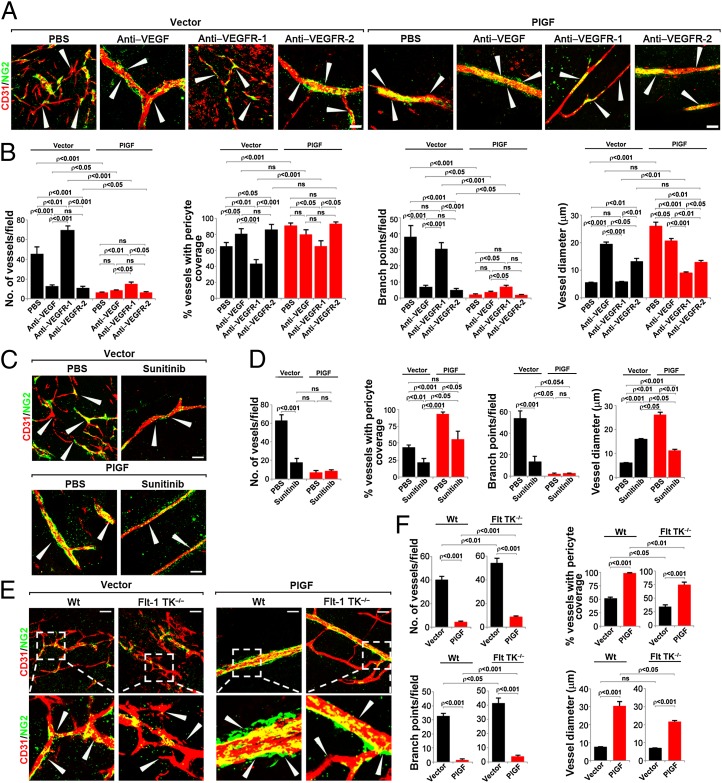

Suppression of PlGF T241 Tumor Angiogenesis by Anti-VEGF Agents.

Immunofluorescence analysis of tumor blood vessels showed that VEGF and VEGFR-2 blockades significantly inhibited angiogenesis in PlGF-T241 tumors (Fig. 4 A and B). The antiangiogenic effects of VEGF and VEGFR-2 blockades in PlGF T241 tumors were at least equivalent to those seen in vector T241 tumors, demonstrating that expression of PlGF in tumors did not contribute to drug resistance of anti-VEGF agents. It should be noted that VEGF and VEGFR-2 blockade treatment did not significantly alter pericyte coverage. Compared with VEGF and VEGFR-2 blockades, VEGFR-1 blockade treatment significantly increased the number of tumor microvessels compared with the vehicle-treated tumors (Fig. 4 A and B). Similar to VEGFR-2 blockade, treatment of PlGF T241 tumors with sunitinib (28) resulted in markedly increased antiangiogenic activity, which appeared to be greater than sunitinib-treated vector T241 tumors (Fig. 4 C and D). Interestingly, sunitinib also significantly reduced pericyte coverage in both PlGF T241 and vector T241 tumors. This finding is consistent with the broad spectrum targets of sunitinib, which also blocks the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR)-mediated signaling system, an essential pathway for pericyte coverage in angiogenic vessels. To further validate the negative role of VEGFR-1 in mediating repressive signals of tumor angiogenesis, T241 tumors were implanted in VEGFR-1 tyrosine kinase (TK)−/− mice that carry a mutated VEGFR-1 lacking the TK domain (29). As expected, T241 tumors in VEGFR-1 TK−/− mice contained a significantly higher vascular density compared with those in WT littermates (Fig. 4E). Intriguingly, tumor angiogenesis in VEGFR-1 TK−/− mice appeared to be resistant to VEGFR-2 blockade compared with that in WT littermates (Fig. 4E). Similar to T241 vector tumors, PlGF T241 tumors in VEGFR-1 TK−/− mice contained a significantly higher number of blood vessels compared with the tumor vasculature in WT mice (Fig. 4 E and F). These findings suggest that the TK domain of VEGFR-1 is involved in transducing repressive signals of tumor angiogenesis.

Fig. 4.

Microvasculatures in vehicle- and anti-VEGF–treated vector T241 and PlGF T241 tumors in WT and Flt-1 TK−/− mice. (A) Representative micrographs of CD31-positive tumor vessels in vehicle-, VEGF blockade–, VEGFR-1 blockade–, and VEGFR-2 blockade–treated vector T241 or PlGF T241 tumors. Red, CD31-positive signal; green, NG2-positive signal. Arrowheads point to vessels. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (B) Quantification of microvessel numbers, branch points, pericyte coverage, and vessel diameter in vehicle-, VEGF blockade–, VEGFR-1 blockade–, and VEGFR-2 blockade–treated vector T241 or PlGF T241 tumors (8–11 samples per group). (C) Representative micrographs of CD31-positive tumor vessels in vehicle- and sunitinib-treated vector T241 or PlGF T241 tumors. Red, CD31-positive signal; green, NG2-positive signal. Arrowheads point to vessels. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (D) Quantification of microvessel numbers, branch points, pericyte coverage, and vessel diameter in vehicle- and sunitinib-treated vector T241 or PlGF T241 tumors (4–11 samples per group). (E) Representative micrographs of CD31-positive tumor vessels in vector T241 or PlGF-tumors in WT or Flt-1 TK−/− mice. Red, CD31-positive signal; green, NG2-positive signal. Arrowheads point to vessels. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (F) Quantification of microvessel numbers, branch points, pericyte coverage, and vessel diameter in vector T241 and PlGF T241 tumors in WT (3–4 mice per group) or Flt-1 TK−/− mice (3–4 mice per group) (6–13 samples per group).

Vascular Perfusion and Permeability.

To study functional impacts of anti-VEGF–induced vascular alterations, 70- and 2,000-kDa lysine-fixable tetramethylrhodamine dextrans (LRDs) were used to measure vascular permeability and perfusion. PlGF-normalized vessels showed markedly reduced permeability compared with vector T241 tumor vessels (Fig. S5 A and B). In vector T241 tumors, VEGF and VEGFR-2 blockades significantly reduced extravasation of 70-kDa LRD, supporting the fact that anti-VEGF agents significantly normalize tumor vessels (Fig. S5 A and B). Conversely, VEGFR-1 blockade further increased vascular leakage compared with the vehicle-treated T241 tumors (Fig. S5 A and B). Similarly, VEGFR-1 blockade also significantly increased vascular permeability of PlGF T241 tumors, whereas VEGF and VEGFR-2 blockades did not significantly affect vascular permeability of PlGF-expressing tumors (Fig. S5 A and B). These findings demonstrate that expression of PlGF in tumors significantly normalizes tumor vessels against vascular leakage and that blocking VEGFR-1 leads to an increased vascular leakage. Thus, VEGFR-1–mediated signals may be involved in vascular remodeling against vascular leakage.

Consistent with the normalization function of PlGF, the ratio of perfused vessels vs. the total number of vessels in PlGF T241 tumors was significantly increased (Fig. S5 C and D). The PlGF-induced vascular perfusion was neutralized by VEGFR-1 blockade. Interestingly, both VEGF and VEGFR-2 blockades significantly increased vascular perfusion in vector T241 tumors but not in PlGF T241 tumors (Fig. S5 C and D). These data show PlGF significantly contributes to the ratio of functional vessels vs. the total number of tumor vessels.

Discussion

Unlike its related member VEGF, the angiogenic and tumor promoting activity of PlGF remains ambiguous and controversial (30). PlGF was found to promote angiogenesis and tumor growth in certain animal models (9). In light of this positive function, anti-cancer therapeutic agents by targeting PlGF have been developed and an anti-PlGF–neutralizing antibody shows potent antiangiogenic and antitumor effects in mouse tumor models (9). Furthermore, PlGF-induced tumor angiogenesis was shown to confer anti-VEGF drug resistance, which was counteracted by the anti-PlGF antibody (9). Conversely, several other laboratories including our own have reported the opposite effect of PlGF, which suppresses tumor angiogenesis and tumor growth when overexpressed in tumor cells (14, 16–18). Recently, a rigorous study showed that, in 15 tumor models, four independent PlGF-neutralizing antibodies had no significant effect on tumor angiogenesis (22). These controversial findings of PlGF in modulation of tumor angiogenesis, tumor growth, and therapeutic assessment indicate that blocking PlGF for cancer therapy is challenging.

In these studies, the spatiotemporal relation of PlGF to VEGF production in the tumor microenvironment was not understood. For example, from which cell types is PlGF produced in the tumor environment? If PlGF is synthesized from tumor cells, what is its expression level in relation to VEGF? As PlGF positively and negatively modulates VEGF-induced tumor angiogenesis depending on its relation to VEGF production (5), defining the cell population that produces both factors is crucial to understand its function. The above-mentioned discrepant reports might be caused by the fact that PlGF is produced from different cells in the tumor environment. PlGF–VEGF heterodimers exhibit only a modest activity on stimulation of angiogenesis compared with VEGF homodimers (31). This finding was validated in a mouse fibrosarcoma model that overexpressed PlGF-1 or PlGF-2. Given the universal high expression levels of VEGF in most tumors that are often exposed to tissue hypoxia, dimerization between VEGF and PlGF would inevitably occur if PlGF is expressed in the tumor microenvironment. Comparative studies of PlGF-1– and PlGF-2–transfected T241 tumors under the same experimental settings demonstrate that no significant difference was found between these two isoforms of PlGF in regulation of tumor growth, neovascularization, vascular perfusion, and vascular leakage (Fig. S4). These findings also indicate that PlGF-modulated tumor growth, angiogenesis, and anti-VEGF drug responses are independent from alternative splicing of the plgf transcripts.

One of the most surprising findings in the current study is the hypersensitivity of PlGF-expressing tumors to anti-VEGF agents. Using three independent VEGF blocking agents including a VEGF-neutralizing antibody, a VEGFR-2–neutralizing antibody, and sunitinib, we provide compelling evidence that PlGF-expressing human and mouse tumors are superiorly sensitive to these anti-VEGF drugs relative to non–PlGF-producing tumors. Notably, anti-VEGF drugs are able to induce dormancy of avascular tumors in a small number of PlGF-expressing tumor-bearing mice compared with non–PlGF-expressing tumor-bearing mice. The hypersensitivity of PlGF-expressing tumors in response to anti-VEGF treatment is associated with PlGF because loss of function by knocking down of PlGF in human tumors leads to anti-VEGF resistance. Independent evidence was obtained using gain of function of PlGF in a mouse tumor model. Initially, we expected that PlGF would confer anti-VEGF resistance as reported by another study (9). Surprisingly, PlGF in different tumor models augments anti-VEGF sensitivity. Although detailed molecular mechanisms underlying PlGF-increased anti-VEGF sensitivity need to be further defined, PlGF-associated vascular remodeling may play a crucial role in modulation of anti-VEGF responses. In both human and mouse tumor models, we show that PlGF markedly remodels the disorganized tumor blood vessels toward a normalized phenotype, which appears as sparsely pruned and dilated vasculatures. Why would PlGF-normalized vessels be more prone to anti-VEGF treatment? One explanation would be that the negligible amount of VEGF homodimers in the tumor environment is essential for maintaining vessel survival. Delivery of anti-VEGF agents to PlGF-expressing tumors may result in nearly functional depletion of VEGF homodimers, leading to marked vascular regression. In support of this view, treatment of PlGF-expressing human tumors with VEGF or VEGFR-2 blockades leads to dormancy of a small number of avascular tumors that virtually lack detectable blood vessels. Indeed, numerous published reports have shown that VEGF is a potent survival factor for physiological and pathological vessels (32–34). The other possibility is that PlGF-normalized tumor vessels increase anti-VEGF drug delivery in the tumor microenvironment. In support of this notion, PlGF-normalized vessels were less leaky and showed improved vascular perfusion. However, we cannot exclude other possibilities in which PlGF synergistically inhibits tumor growth with anti-VEGF agents, including vasculogenesis and inflammation.

Another important finding is that VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2 blocking antibodies produced opposing effects in tumor neovascularization. Whereas VEGFR-2 blockade markedly suppressed tumor angiogenesis, VEGFR-1 blockade enhanced neovascularization, suggesting that VEGFR-1 may function as a decoy receptor and transduce negative signals. In fact, genetic deletion of the TK domain of VEGFR-1 in mice resulted in significantly enhanced tumor angiogenesis and resistance to VEGFR-2 blockade (29). Based on these findings, it is reasonable to speculate that PlGF–VEGFR-1–mediated suppressive signals and VEGFR-2 blocking agents may synergistically inhibit tumor angiogenesis. Thus, removal of the VEGFR-1 TK domain abolishes PlGF-triggered negative signaling and the tumor gains resistance to VEGFR-2 inhibition. The extension of our findings may also extend to other VEGFR-1 binding members in the VEGF family. For example, VEGF-B also exclusively binds to VEGFR-1, and it has been reported to inhibit tumor growth (35). Although we used choriocarcinoma as an example in our study, this finding may extend to other human tumors where PlGF is expressed.

The clinical implications of the present findings propose that tumor PlGF expression level could potentially be used as a marker to predict anti-VEGF responses. As PlGF is frequently detected in various human tumors, our present findings are highly relevant to human cancer patients. If validated in human cancer patients, measurement of tumor PlGF may become one of the few available biomarkers for selection of anti-VEGF responders. This speculation warrants validation in cancer patients by designing rigorous clinical trials.

Methods

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the North Stockholm Experimental Animal Ethical Committee (Stockholm, Sweden). Statistical analyses were performed using a standard two-tail Student's t test. Details are provided in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zhenping Zhu at ImClone for providing VEGFR-1– and VEGFR-2–specific neutralizing antibodies, and Simcere Pharmaceuticals for providing VEGF blockade. Y.C.’s laboratory is supported by research grants from the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Foundation, the Karolinska Institute Foundation, the Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (CMM-Tianjin, No. 09ZCZDSF04400) for international collaboration between Tianjin Medical University and Karolinska Institutet, a Karolinska Institute distinguished professor award, the Torsten Söderbergs Foundation, Söderbergs Stiftelse, ImClone Systems/Eli Lilly, the European Union Integrated Project of Metoxia (Project 222741), and the European Research Council advanced grant ANGIOFAT (Project 250021).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1209310110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cao Y, et al. 2011. Forty-year journey of angiogenesis translational research. Sci Transl Med 3(114):114rv113.

- 2.Cao Y, Langer R. Optimizing the delivery of cancer drugs that block angiogenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(15):ps3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2039–2049. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maglione D, Guerriero V, Viglietto G, Delli-Bovi P, Persico MG. Isolation of a human placenta cDNA coding for a protein related to the vascular permeability factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(20):9267–9271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.20.9267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao Y. Positive and negative modulation of angiogenesis by VEGFR1 ligands. Sci Signal. 2009;2(59):re1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.259re1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fong GH, Rossant J, Gertsenstein M, Breitman ML. Role of the Flt-1 receptor tyrosine kinase in regulating the assembly of vascular endothelium. Nature. 1995;376(6535):66–70. doi: 10.1038/376066a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maglione D, et al. Two alternative mRNAs coding for the angiogenic factor, placenta growth factor (PlGF), are transcribed from a single gene of chromosome 14. Oncogene. 1993;8(4):925–931. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van de Veire S, et al. Further pharmacological and genetic evidence for the efficacy of PlGF inhibition in cancer and eye disease. Cell. 2010;141(1):178–190. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fischer C, et al. Anti-PlGF inhibits growth of VEGF(R)-inhibitor-resistant tumors without affecting healthy vessels. Cell. 2007;131(3):463–475. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luttun A, et al. Revascularization of ischemic tissues by PlGF treatment, and inhibition of tumor angiogenesis, arthritis and atherosclerosis by anti-Flt1. Nat Med. 2002;8(8):831–840. doi: 10.1038/nm731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmeliet P, et al. Synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and placental growth factor contributes to angiogenesis and plasma extravasation in pathological conditions. Nat Med. 2001;7(5):575–583. doi: 10.1038/87904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odorisio T, Cianfarani F, Failla CM, Zambruno G. The placenta growth factor in skin angiogenesis. J Dermatol Sci. 2006;41(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odorisio T, et al. Mice overexpressing placenta growth factor exhibit increased vascularization and vessel permeability. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 12):2559–2567. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.12.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedlund EM, Hosaka K, Zhong Z, Cao R, Cao Y. Malignant cell-derived PlGF promotes normalization and remodeling of the tumor vasculature. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(41):17505–17510. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908026106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Björndahl M, Cao R, Eriksson A, Cao Y. Blockage of VEGF-induced angiogenesis by preventing VEGF secretion. Circ Res. 2004;94(11):1443–1450. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000129194.61747.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eriksson A, et al. Placenta growth factor-1 antagonizes VEGF-induced angiogenesis and tumor growth by the formation of functionally inactive PlGF-1/VEGF heterodimers. Cancer Cell. 2002;1(1):99–108. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu L, et al. Placenta growth factor overexpression inhibits tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis by depleting vascular endothelial growth factor homodimers in orthotopic mouse models. Cancer Res. 2006;66(8):3971–3977. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schomber T, et al. Placental growth factor-1 attenuates vascular endothelial growth factor-A-dependent tumor angiogenesis during beta cell carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2007;67(22):10840–10848. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cao Y, et al. Heterodimers of placenta growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. Endothelial activity, tumor cell expression, and high affinity binding to Flk-1/KDR. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(6):3154–3162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiSalvo J, et al. Purification and characterization of a naturally occurring vascular endothelial growth factor.placenta growth factor heterodimer. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(13):7717–7723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer C, Mazzone M, Jonckx B, Carmeliet P. FLT1 and its ligands VEGFB and PlGF: drug targets for anti-angiogenic therapy? Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(12):942–956. doi: 10.1038/nrc2524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bais C, et al. PlGF blockade does not inhibit angiogenesis during primary tumor growth. Cell. 2010;141(1):166–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu Y, et al. A humanized anti-VEGF rabbit monoclonal antibody inhibits angiogenesis and blocks tumor growth in xenograft models. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(2):e9072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shibuya M. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (VEGFR-1/Flt-1): A dual regulator for angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2006;9(4):225–230, discussion 231. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9055-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao R, et al. VEGFR1-mediated pericyte ablation links VEGF and PlGF to cancer-associated retinopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(2):856–861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911661107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue Y, et al. Anti-VEGF agents confer survival advantages to tumor-bearing mice by improving cancer-associated systemic syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(47):18513–18518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807967105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue Y, et al. PDGF-BB modulates hematopoiesis and tumor angiogenesis by inducing erythropoietin production in stromal cells. Nat Med. 2012;18(1):100–110. doi: 10.1038/nm.2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motzer RJ, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hiratsuka S, Minowa O, Kuno J, Noda T, Shibuya M. Flt-1 lacking the tyrosine kinase domain is sufficient for normal development and angiogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(16):9349–9354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ribatti D. The controversial role of placental growth factor in tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 2011;307(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao Y, Linden P, Shima D, Browne F, Folkman J. In vivo angiogenic activity and hypoxia induction of heterodimers of placenta growth factor/vascular endothelial growth factor. J Clin Invest. 1996;98(11):2507–2511. doi: 10.1172/JCI119069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamba T, et al. VEGF-dependent plasticity of fenestrated capillaries in the normal adult microvasculature. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290(2):H560–H576. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00133.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee S, et al. Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis. Cell. 2007;130(4):691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alon T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a survival factor for newly formed retinal vessels and has implications for retinopathy of prematurity. Nat Med. 1995;1(10):1024–1028. doi: 10.1038/nm1095-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albrecht I, et al. Suppressive effects of vascular endothelial growth factor-B on tumor growth in a mouse model of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumorigenesis. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e14109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.