Abstract

NF-κB is the master regulator of the immune response and is responsible for the transcription of hundreds of genes controlling inflammation and immunity. Activation of NF-κB occurs in the cytoplasm through the kinase activity of the IκB kinase complex, which leads to translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus. Once in the nucleus, NF-κB transcriptional activity is regulated by DNA binding-dependent ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation. We have identified the deubiquitinase Ubiquitin Specific Protease-7 (USP7) as a regulator of NF-κB transcriptional activity. USP7 deubiquitination of NF-κB leads to increased transcription. Loss of USP7 activity results in increased ubiquitination of NF-κB, leading to reduced promoter occupancy and reduced expression of target genes in response to Toll-like– and TNF-receptor activation. These findings reveal a unique mechanism controlling NF-κB activity and demonstrate that the deubiquitination of NF-κB by USP7 is critical for target gene transcription.

Inflammation represents the immune response to infection or tissue damage and is critical for host survival. It requires the coordinated expression of cytokines, chemokines, antimicrobial peptides, and factors important for tissue repair and regeneration. The transcription factor NF-κB is critical for the expression of these inflammatory proteins and is regarded as the master regulator of the immune response (1). The primary mode of control of NF-κB transcriptional activity is through its sequestration in the cytoplasm by the IκB family of proteins of which IκBα is the archetypal member (2). Upon receipt of an inducing stimulus, such as a Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligand or TNFα, IκBα is phosphorylated by the IKK complex, which targets it for ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal-mediated degradation. The resulting free NF-κB dimers then translocate to the nucleus where they may bind to their cognate sites in the regulatory regions of target genes.

Translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus, however, is not sufficient for its optimal transcriptional activity, and recent studies have identified a number of essential regulators of NF-κB in the nucleus (3, 4). Of the identified nuclear regulators of NF-κB there is a preponderance of factors that regulate NF-κB ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Included in this group are GCN5 (5), Pin1 (6), PDLIM2 (7), COMMD1 (8), SOCS1 (6), and Bcl-3 (9). The ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of NF-κB has been demonstrated to be critical in the termination of the NF-κB transcriptional response and represents a major limiting factor in the expression of proinflammatory genes (10, 11). Importantly, the ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of NF-κB p65 affects a small pool of nuclear p65 that is DNA bound at target promoters (10–13). Thus, the NF-κB–mediated transcription of a target gene is directly linked with the proteolytic destruction of NF-κB itself (9, 10).

Analogous to phosphorylation, ubiquitination of proteins is countered by an opposing deubiquitination activity that proteolytically removes polyubiquitin chains from substrates (14). Of the deubiquitinases studied to date, Ubiquitin Specific Protease-7 (USP7) or herpesvirus-associated ubiquitin-specific protease (HAUSP) has the clearest biological role as a regulator of transcription (15). Originally identified as a herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV1) Vmw110 interacting protein (16), USP7 also interacts with the Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 (EBNA1) protein and HSV1 IPC0, which can induce the nuclear export of USP7 following infection (17). Identified targets of USP7 deubiquitinase activity include the tumor suppressor protein p53 (18) and its regulator murine double minute (mdm2) (19), PTEN (20), INK4a (21), TSPYL5 (22), Ataxin-1 (23), and the transcription factors FOXO4 (24) and REST (25). The effects of USP7 deubiquitinase activity on these substrates includes enhanced stability as well as altered subcellular localization.

Here we report that USP7 is essential for TLR- and TNFα receptor (TNFR)-induced gene expression. We identify NF-κB p65 as a unique substrate for USP7 deubiquitinase activity and demonstrate that USP7 deubiquitination of p65 increases protein stability. We also show that deubiquitination of NF-κB by USP7 is essential for NF-κB transcriptional activity. Remarkably, USP7 is recruited to NF-κB target promoters following receptor activation and interacts with NF-κB in a DNA-binding–dependent manner. These data indicate a unique mechanism of transcription factor recycling at target promoters to enhance gene expression. The efficacy of pharmacological inhibition of USP7 in reducing inflammatory gene expression indicates that the deubiquitination of NF-κB described here may have therapeutic potential.

Results

Decreased Expression of TLR- and TNFR-Inducible Genes Following USP7 Inhibition in Macrophage.

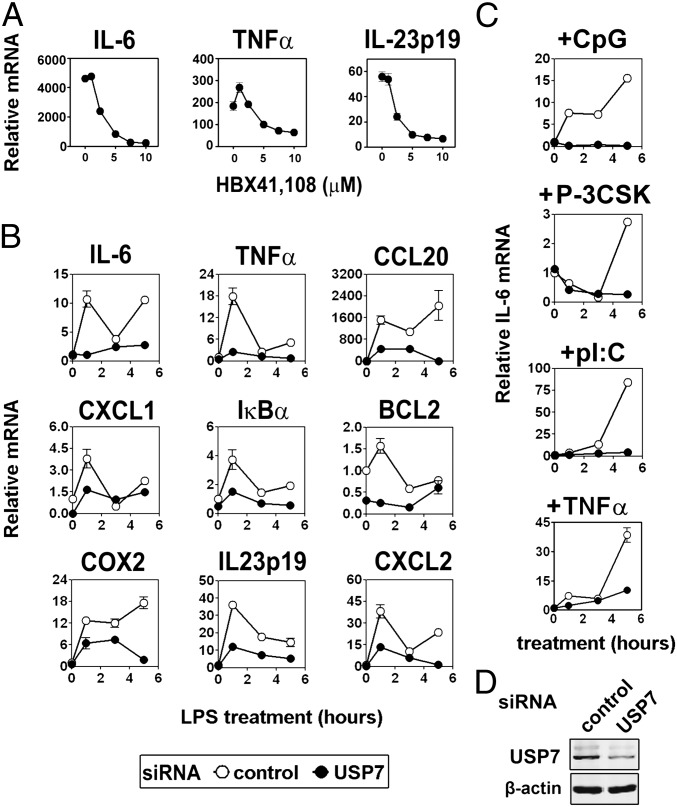

A key role for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation in the control of NF-κB transcription activity has previously been described (8–10). However, little attention has been paid to the contribution of opposing deubiquitinase activity in the control of NF-κB transcriptional activity (26). We screened the inhibitor HBX41,108, which, although not extensively characterized, demonstrates specificity for USP7 (27), for its ability to alter LPS-induced gene expression in murine bone marrow derived macrophage. HBX41,108 dose dependently inhibited the LPS-induced expression of IL-6, TNFα, and IL-23p19 (Fig. 1A). Similar inhibition of LPS-induced gene expression was seen in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells transfected with control siRNA or siRNAs directed against USP7 (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). USP7 knockdown also inhibited (S)-[2,3-Bis(palmitoyloxy)-(2-RS)-propyl]-N-palmitoyl-(R)-Cys-(S)-Ser-(S)-Lys4-OH (PAM(3)CSK) (TLR1/2 ligand)-, CpG (TLR9 ligand)-, Poly I:C (TLR3 ligand)-, and TNFα-induced IL-6 expression (Fig. 1C). Knockdown of USP7 was confirmed by immunoblot (Fig. 1D). Together these data identify USP7 as an essential factor for TLR and TNFR-induced inflammatory gene expression.

Fig. 1.

USP7 knockdown inhibits cytokine gene expression. (A) Murine bone marrow–derived macrophage was pretreated with the indicated concentration of HBX41,108 for 1 h before stimulation with LPS. mRNA levels were assessed by qPCR. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples. (B) RAW 264.7 macrophage was transfected with control siRNA (open circles) or siRNA directed against USP7 (filled circles). Cells were stimulated 24 h posttransfection with 100 ng/mL LPS for the indicated times before mRNA levels were assessed by qPCR. Data shown are mean ± SD of triplicate samples and representative of three independent experiments. (C) Control or USP7 knockdown cells treated with CpG, Pam-3CSK (P-CSK), poly(I:C) (pI:C), or TNFα as indicated. IL-6 mRNA levels were assessed by qPCR. (D) Immunoblot analysis of RAW 264.6 macrophage cells tansfected with USP7 or Scrambled siRNA (control) using anti-USP7 and anti-β-actin antibodies.

USP7 Is Essential for LPS and TNF-α–Induced NF-κB Transcriptional Activity.

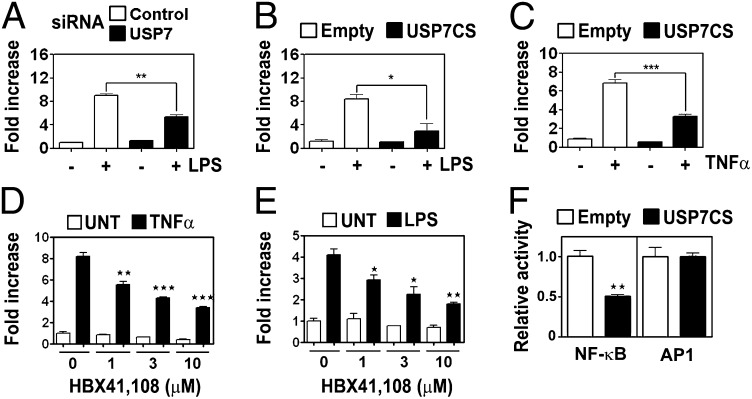

The transcription factor NF-κB is a key regulator of both TLR and TNFR-inducible genes including those inhibited by USP7 knockdown. RAW 264.7 cells transfected with USP7 siRNA showed significantly lower LPS-induced NF-κB reporter activity compared with control siRNA transfected cells (Fig. 2A). A similar effect on LPS-induced NF-κB reporter activity was also seen in cells transfected with a dominant negative form of USP7 (USP7CS) in which the critical cysteine (C223) in the catalytic site has been mutated to a serine (Fig. 2B). Similar results were obtained with NIH 3T3 cells (Fig. S2) and USP7CS expressing HEK293T treated with TNFα (Fig. 2C). The treatment of cells with HBX41,108 also inhibited TNFα- and LPS-induced NF-κB reporter activity (Fig. 2 D and E). Conversely, the overexpression of USP7 increased basal NF-κB reporter activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. S2). The expression of USP7CS had no effect on the AP1 transcriptional reporter activity, suggesting that USP7 is a specific regulator of NF-κB activity (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

USP7 depletion impairs NF-κB signaling. (A) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were transfected with USP7 siRNA or Scrambled siRNA (control) and, 24 h later, were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids. A total of 48 h later, the cells were stimulated with LPS or left untreated. Shown is relative NF-κB luciferase activity (fold increase). (B) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were cotransfected with USP7 dominant negative (USP7CS) and NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmids. (C) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with USP7 dominant negative (USP7CS) and NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmids and stimulated with TNFα or left untreated. (D) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with IL-23p19 promoter luciferase reporter plasmid. The cells, 24 h later, were left untreated or pretreated with the indicated concentration of HBX41,108 for 1 h before stimulation with TNFα. (E) RAW264.7 macrophage cells were cotransfected with IL-23p19 promoter luciferase reporter plasmid. The cells, 24 h later, were left untreated or pretreated with the indicated concentration of HBX41,108 for 1 h before stimulation with LPS. (F) Luciferase activity in RAW 264.7 macrophage cells cotransfected with USP7 dominant negative (USP7CS) and NF-κB or AP-1 luciferase reporter plasmids.

Because p53 and mdm2 are USP7 substrates, we assessed the effect of USP7 inhibition in p53−/−/mdm2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). The stimulation of p53−/−/mdm2−/− MEFs with TNFα resulted in a NF-κB transcriptional response that was also inhibited by the overexpression of USP7CS (Fig. S3 A and B). These data demonstrate that the regulation of NF-κB activity by USP7 is not dependent on Mdm2 or p53.

USP7 Promotes NF-κB DNA Binding.

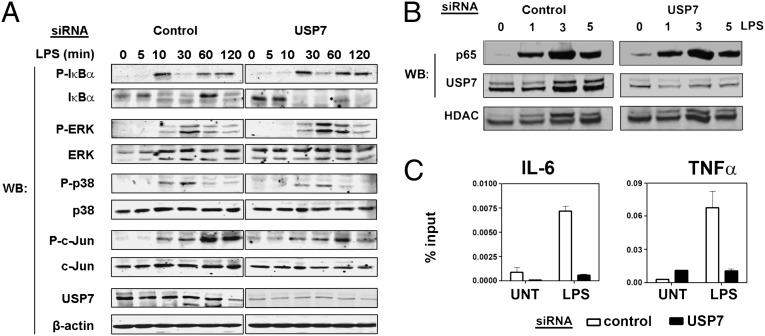

We were unable to discern any significant differences in the activation of signal transduction pathways downstream of TLR4 between control and USP7 siRNA treated cells (Fig. 3A). Similar results were obtained in TNFα-treated HEK293T cells overexpressing USP7CS and LPS-stimulated RAW macrophage pretreated with HBX41,108 (Fig. S4). In addition, the nuclear translocation of the NF-κB p65 subunit, as assessed by immunoblot analysis of nuclear fractions, was also unaffected by USP7 knockdown in LPS-stimulated cells compared with controls (Fig. 3B). However, the recruitment of p65 to the IL-6 and TNFα promoters was inhibited in USP7 knockdown cells as determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (Fig. 3C and Fig. S1). These data suggest that USP7 regulates NF-κB proximal to the promoter rather than at a point upstream in the TLR or TNFR signaling pathways.

Fig. 3.

USP7 promotes NF-κB DNA binding. (A) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were transfected with USP7 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (control) and 24 h later stimulated with LPS for the indicated time points before immunoblot analysis using the indicated antibodies. (B) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were transfected with USP7 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (control) and 24 h later stimulated with LPS for the indicated time points. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were analyzed by immunoblot with the indicated antibodies. (C) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were stimulated with 100 ng/mL LPS for 6 h and followed by chromatin immunoprecipitation using anti-p65 and normal rabbit IgG (control) antibodies. Chromatin immunoprecipitations were analyzed using primers flanking the IL-6 and TNFα promoter regions.

NF-κB Interacts with USP7 in a DNA-Binding–Dependent Manner.

The data obtained above suggest that NF-κB may be directly regulated by USP7. USP7 was readily detected in immunoprecipitates of p65 from cotransfected cells, demonstrating the interaction of USP7 and p65 (Fig. 4A). The interaction between endogenous p65 and USP7 is weakly detectable in unstimulated cells and is significantly enhanced following LPS stimulation (Fig. 4B), an observation explained by the colocalization of p65 with USP7 in the nucleus following stimulation. In addition, USP7 was also found to interact with the c-Rel, p50, p52, and RelB subunits when cotrasnfected (Fig. S5).

Fig. 4.

USP7 interacts with NF-κB. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected with p65 and FLAG-USP7 plasmids. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted with antibodies indicated. (B) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were stimulated with LPS and lysates immunoprecipitated with anti-USP7 antibody and immunoblotted with anti-p65 antibody. (C) HEK293T cells were transfected with p65 and full-length USP7 (USP7 FL) and USP7 deletion mutants as indicated. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted for USP7. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with WT p65, p65C197A/R198A, p65R267A, or p65R329A/R330AA, and FLAG-USP7 plasmids. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted with antibodies indicated. Longer exposure of anti-USP7 immunoblot is also shown. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with p65, p65 DNA binding mutant (p65Y36D, D39E), p65 S536A and S536E mutants, and with FLAG-USP7 plasmids. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with p65 antibody and immunoblotted with anti-USP7 antibody. (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with p65, p65S468A, and FLAG-USP7 plasmids. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted for USP7.

In addition to a catalytic peptidase domain, USP7 contains an N-terminal meprin and TRAF homology (MATH) or tumour necrosis factor receptor associated factor (TRAF)-like domain and 5 ubiquitin-like (UbL) domains in the C-terminal region. To determine the domains required for USP7 interaction with p65, we generated USP7 mutants that lacked the MATH domain (USP7∆MATH), the Ubl domains (USP7∆UBL), or contained only the MATH domain (MATH) (Fig. S6). The USP7 MATH domain alone does not coimmunoprecipitate with p65 when coexpressed (Fig. 4C). Indeed, the MATH domain appears to be dispensable for the interaction of USP7 with p65, as the USP7∆MATH mutant strongly coimmunoprecipitates with p65 (Fig. 4C). Deletion of the C-terminal Ubl domains, however, abolishes the interaction of USP7 with p65, demonstrating that this region is critical for interaction with p65 (Fig. 4C).

To identify the regions of p65 required for interaction with USP7, we used peptide arrays comprised of overlapping peptides (18 mers) encompassing the entire sequence of p65. Peptide arrays were incubated with purified recombinant USP7 derived from insect cells and USP7-bound peptides identified by immunoblotting with anti-USP7 antibodies. This analysis identified three regions of p65 that may be of potential importance in mediating the interaction of p65 with USP7 (Fig. S6). By using peptide scanning arrays in which successive amino acids of specific peptides were substituted by alanine, we found that alanine substitutions for R198, R267, R273, R329, and R330 significantly inhibited USP7 binding (Fig. S6). A survey of the X-ray crystal structure of p65 revealed that residues R198 and R267 but not R273 are contained on the surface of p65 and are therefore available for interaction with USP7 (Fig. S6). Residues 329 and 330 are not represented on the available structures. Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis revealed that a p65R198A mutant interacted with USP7 to the same extend as WT p65. However, p65R267A and p65R329A/R330A mutants showed an almost complete loss of interaction with USP7, with some residual interaction detectable on extended exposure of immunoblots (Fig. 4D). These data identify R267, R329, and R330 as critical residues of p65 that mediate the interaction with USP7.

DNA binding and phosphorylation at serines 536 and 468 have been identified as critical regulators of p65 ubiquitination and transcriptional activity (11, 12, 28). HEK293T cells were cotransfected with USP7 along with WT p65, a p65S536A mutant, or a DNA binding defective p65Y36D, D39E mutant and immunoprecipitated using an antibody against p65. Immunoblot analysis of coimmunoprecipitated USP7 demonstrated reduced interaction between USP7 and a p65S536A mutant and a p65Y36D, D39E mutant defective in DNA binding. The mutation of S536 to the phosphomimetic amino acid glutamate (p65S536E) had no effect on the interaction of USP7 and p65 (Fig. 4E). Phosphorylation at S468 has recently been demonstrated to be necessary for COMMD1-mediated ubiquitination of p65 and proteasomal degradation (12), however the interaction of p65 and USP7 was not altered by mutation of S468 to alanine, suggesting that phosphorylation at this site may be required for the ubiquitination but not the deubiquitination of p65 (Fig. 4F).

USP7 Is a NF-κB Deubiquitinase.

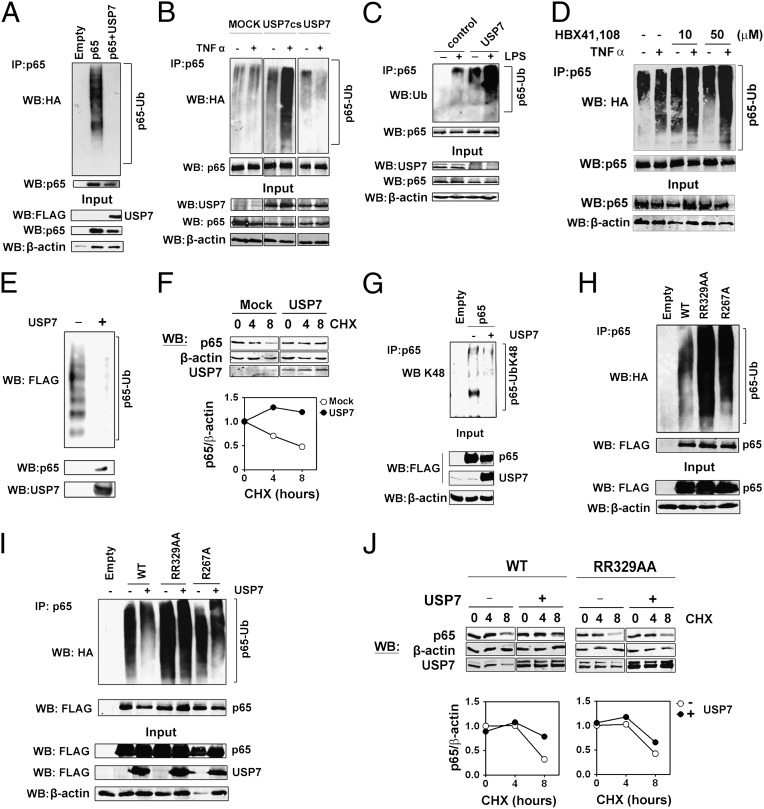

We next investigated whether USP7 is a NF-κB deubiquitinase. Coexpression of USP7 dramatically reduced the amount of ubiquitinated p65 relative to controls (Fig. 5A). The TNFα-inducible ubiquitination of endogenous p65 was enhanced by expression of a USP7CS dominant negative mutant and inhibited by overexpression of wild-type USP7 (Fig. 5B). USP7 knockdown increased basal ubiquitination of endogenous p65 in untreated RAW 264.7 cells and further increased p65 ubiquitination over control levels following LPS treatment (Fig. 5C and Fig. S1). HBX41,108 treatment increased p65 ubiquitination in both untreated and TNFα treated cells (Fig. 5D) but did not alter NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) ubiquitination in line with previous reports (17) (Fig. S7). To establish that USP7 is acting directly on p65 to reduce polyubiquitination, we next performed an in vitro deubiquitination assay using purified ubiquitinated recombiniant p65 generated by an in vitro ubiquitination assay and purified insect-derived recombinant USP7. Recombinant USP7 effectively deubiquitinates polyubiquitinated p65 as demonstrated not only by the disappearance of ubiquitinated p65 but by the concomitant appearance of unmodified p65 in the presence of USP7 (Fig. 5E). Importantly, the levels of p65 protein do not alter dramatically during NF-κB activation but rather the ubiquitination of p65 targets a small pool of transcriptionally active, DNA-bound p65 for degradation (5, 8, 10). We found that the half-life of p65 in cells transfected with USP7 was significantly longer than control transfected cells (Fig. 5F). In addition, immunoblot analysis of p65 ubiquitination in USP7 transfected cells using K48 linkage-specific antibodies demonstrated that USP7 inhibits the degradative K48 polyubiquitination of p65 (Fig. 5G). Expression of USP7 also inhibited COMMD1 and Cullin2-mediated p65 ubiquitination (5) (Fig. S8).

Fig. 5.

USP7 deubiquitinates NF-κB. (A) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and p65 alone or with FLAG-USP7 plasmid. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted with antibody against HA. (B) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-ubiquitin and FLAG-USP7CS and FLAG-USP7 plasmids. Cells were treated 24 h posttransfection with TNFα and whole cell lysates prepared. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted with antibody against HA. (C) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were transfected with control or USP7 or siRNA and stimulated with LPS for 60 min. MG1332 (10 μM) was added for the final 30 min. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with anti-p65 antibody and immunoblotted with anti-ubiquitin antibody. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-ubiquitin, and 24 h posttransfection, cells were left untreated or pretreated with the indicated concentration of HBX41,108 for 60 min before treatment with TNFα for a further 60 min. MG1332 (10 μM) was added for the final 30 min. Whole cell lysates were prepared and equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted with antibody against HA. (E) Recombinant p65 was in vitro ubiquitinated with FLAG-ubiquitin, purified, and incubated with recombinant USP7 and analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies for FLAG, p65, and USP7. (F) HEK293T cells were transfected with empty or USP7 expression vector. After 24 h, cells were treated with cyclohexamide for the indicated times before immunoblot analysis. Relative levels of p65 protein normalized against β-actin are plotted. (G) HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmids for p65 along with FLAG-USP7 or empty vector. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted with anti-K48 ubiquitin chain antibody. (H) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and plasmids for WT p65, p65R267A, or p65R329A/R330AA. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with anti-p65 antibody and immunoblotted with anti-HA antibody. (I) HEK293T cells were cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and plasmids for WT p65, p65R267A, or p65R329A/R330AA along with FLAG-USP7 or empty vector. Equal amounts of protein were immunoprecipitated with antibody against p65 and immunoblotted with antibody against HA. (J) HEK293T cells were transfected with WT p65 or p65R329A/R330AA expression plasmids as indicted along with empty or USP7 expression vector. After 24 h, cells were treated with cyclohexamide for the indicated times before immunoblot analysis. Relative levels of p65 protein normalized against β-actin are plotted.

Recent studies have reported that p65 may be ubiquitinated on a number of lysines (13). We analyzed a series of p65 mutants containing lysine to arginine substitutions including K310 (p65K10R); combined mutations at K122, K123, K314, and K315 (p65K4R); combined mutations of K122, K123, K314, K315, and K310 (p65K5R); and combined mutations of K52, K62, K79, and K195 (K4RNonAc) (13). The coexpression of USP7 reduced the ubiquitination of all p65 mutants tested, demonstrating that USP7 activity is not restricted to p65 ubiquitinated on a specific lysine residue (Fig. S8). We also found increased ubiquitination in the USP7-interaction-defective p65R329A/R330A and p65R267A mutants, which overexpression of USP7 was unable to reverse (Fig. 5 H and I). Furthermore, the half-life p65R329A/R330A was not significantly increased by coexpression of USP7 compared with WT p65 (Fig. 5J). Together these data demonstrate that USP7 acts directly to deubiquitinate and stabilize p65 and identifies p65 as a substrate for USP7.

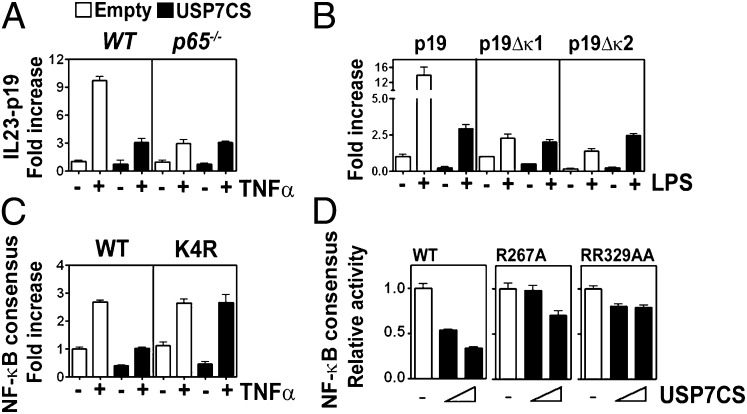

Regulation of Gene Expression by USP7 Requires p65.

To determine the degree to which the regulation of TLR- and TNFα-induced gene expression by USP7 is dependent upon its action on p65, we analyzed the effect of the expression of USP7CS on IL-23p19 promoter reporter activity in WT and p65−/− MEFs. IL-23p19 promoter activity is largely regulated by NF-κB (29), however when p65−/− cells are stimulated with TNFα, there remains a significantly lower, but readily detectable, inducible reporter activity compared with WT cells (Fig. 6A). Remarkably, the expression of the USP7CS in WT cells inhibits the level of reporter activity to a level that closely approximates that of p65−/− cells. Importantly, the expression of USP7CS in p65−/− cells had no effect on TNFα-induced reporter activity (Fig. 6A), demonstrating that p65 is the critical target for USP7 activity following TNFR activation. Using IL-23p19 promoter reporter plasmids lacking either of two essential NF-κB binding sites (29), we found that expression of USP7CS does not inhibit LPS-inducible NF-κB–independent transcription (Fig. 6B). In addition, the transcriptional activity of the p65K4R mutant, which is hypo-ubiquitinated relative to WT p65, is also resistant to inhibition by expression of USP7CS (Fig. 6C) as well as treatment with the USP7 inhibitor HBX41,108 (Fig. S9). The hypo-ubiquitination of p65 K4R is associated with increased protein stability (Fig. S9). Furthermore, both the p65R267A and p65R329A/R330A mutants show significantly reduced transcriptional activity relative to WT p65, which is unaffected by coexpression of USP7CS as measured by NF-κB reporter assay (Fig. 6D). This data demonstrate that ubiquitinated p65 is the target of USP7 activity in the regulation of gene expression.

Fig. 6.

USP7 regulates transcription through p65 ubiquitination. (A) WT or p65−/− MEFs were transfected with IL-23p19 promoter reporter constructs along with empty vector (Empty) or a USP7CS expression vector. After 24 h, cells were stimulated with TNFα (+) or left untreated (–) and luciferase activity measured. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples. (B) RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were cotransfected with USP7 dominant negative (USP7CS) and IL-23p19 promoter luciferase reporter plasmid (p19), and IL-23p19 promoter luciferase reporter plasmids in which the NF-κB binding sites at position –95 (p19Δκ1) or position –600 (p19Δκ2) have been mutated. After 24 h, the cells were stimulated with LPS (+) or left untreated (–) and luciferase activity measured. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples. (C) p65−/− MEFs stably expressing WT p65 or p65K4R were cotransfected with USP7 dominant negative (USP7CS) and NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmids. After 24 h, cells were stimulated with TNFα (+) or left untreated (–) and luciferase activity measured. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples. (D) HEK293T cells were transfected with NF-κB luciferase reporter plasmid and plasmids for WT p65, p65R267A, or p65R329A/R330AA as indicted along with empty vector or increasing amounts of USP7CS expression vector. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h posttransfection. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of triplicate samples.

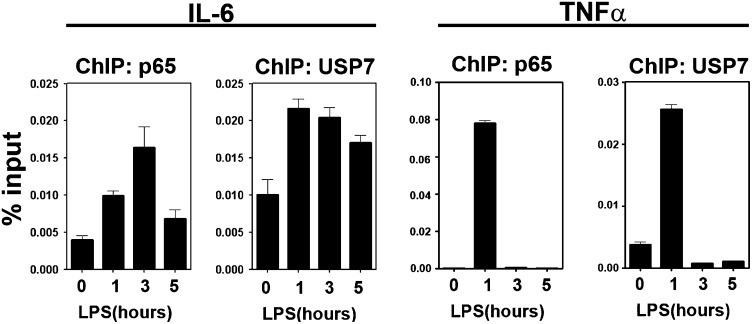

USP7 Is Recruited to NF-κB Target Promoters.

The previously identified link between NF-κB DNA binding and ubiquitination and our findings that USP7 does not interact with a DNA binding mutant of p65 suggest that the interaction of USP7 and p65 may occur at the promoter regions of NF-κB target genes. Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays demonstrated the recruitment of p65 and USP7 to the IL-6 and TNFα promoters following LPS stimulation (Fig. 7). These data suggest that p65 ubiquitination and interaction with UPS7 occurs locally on the promoter of NF-κB target genes and that USP7 supports the transcription of NF-κB target genes by regulating p65 ubiquitination, and thereby its stability, at sites of transcription.

Fig. 7.

USP7 and p65 colocalize on chromatin. RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were stimulated with LPS for the indicated time periods followed by chromatin immunoprecipitation using anti-p65 and anti-USP7 antibodies. Chromatin immunoprecipitations were analyzed using primers flanking the IL-6 and TNFα promoter regions.

Discussion

The deubiquitination of NF-κB by USP7 promotes the expression of NF-κB target genes by opposing the termination of NF-κB transcriptional responses through ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (10, 11). Our findings demonstrate that USP7 controls the balance between the ubiquitination and deubiquitination of NF-κB required for optimum transcription. The emerging complexity of the regulation of NF-κB function proximal to the promoter indicates that the activation of the IKK complex alone is not sufficient for a NF-κB–mediated transcriptional response.

Significantly, the ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation of NF-κB occurs in only a small pool of activated NF-κB dimers. The association of components of the NF-κB E3 ligase complex (12), ubiquitinated p65 (13), proteasomal subunits (10), and USP7 at NF-κB target promoters strongly indicates that this pool of NF-κB is primarily DNA bound and transcriptionally active. This is supported by the dependency of NF-κB ubiquitination on DNA binding of activated dimers (9, 10). Furthermore, mutagenesis of serine 536 not only inhibits the ubiquitination of NF-κB but also dramatically extends the residency time of NF-κB on target promoters (11, 28). The role of DNA as an allosteric regulator of NF-κB has previously been recognized, and there is clear evidence for a DNA-induced conformational change in NF-κB structure (30, 31). Although the precise nature of the DNA-induced NF-κB conformational change is unknown, it is becoming apparent that the regulatory components of the ubiquitination apparatus may differentially interact with DNA-bound versus nucleoplasmic NF-κB. Our data demonstrate that DNA-bound NF-κB preferentially interacts with USP7 over nonbound NF-κB and that NF-κB stability is likely determined by regulators of ubiquitination at the promoters of target genes. Indeed, it is possible that NF-κB interacts with a unique set of regulators when bound to DNA that dictate the transcriptional outcome of a DNA binding event.

The recruitment of USP7 to NF-κB target promoters suggests that USP7 deubiquitinase activity is critical in determining the duration and strength of the NF-κB transcriptional response by opposing promoter-associated ubiquitination activities. Furthermore, it implies a localized regulatory apparatus at sites of transcription that determines the local concentration of NF-κB protein. Such localized regulation at sites of transcription may be important considering that for most transcription factors, including NF-κB, a large fraction are chromatin bound at nontarget sites (32, 33). However, it is unclear if every DNA binding event triggers the ubiquitination of NF-κB or whether ubiquitination occurs only at specific binding sites in the genome. Future analysis of the sites of NF-κB ubiquitination in the nucleus will provide critical insight into this important question. In any case, as this report shows, USP7 may be regarded as promoting the recycling of NF-κB at target promoters by opposing the apparent default of NF-κB DNA-binding–induced degradation. Our data support the notion that circumvention of this default outcome by USP7 is required for a meaningful NF-κB–directed transcriptional response. The proinflammatory nature of many of the transcriptional targets of NF-κB including cytokines and chemokines and their ability to inflict host damage may necessitate such a DNA-binding–induced degradation default. Previous studies have demonstrated that the Herpes Simplex Virus protein ICP0 can mediate the cytoplasmic translocation of USP7 where it interacts with NEMO and TRAF6 (17). Thus, ICP0, by altering USP7 localization, may transform USP7 from a positive to a negative regulator of NF-κB activity.

In summary, the data presented here identify USP7 as a regulator of NF-κB and defines a mechanism for the control of transcription through the active recycling of ubiquitinated NF-κB. We suggest a model whereby the balance of NF-κB ubiquitination and deubiquitination, processes regulated by E3 ligases and USP7, respectively, determines the transcriptional outcome at target genes following TLR and TNFR activation.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture, Transfection, and siRNA Knockdown.

RAW 264.7 macrophage cells, NIH 3T3 cells, HEK293T cells, and p65−/− expressing WT p65 or p65 with four critical lysine residues mutated (K4R) MEFs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS. Transient transfection and siRNA knockdown are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed using Probe Library master mix on a Light Cycler Real Time PCR system (Roche) as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Immunoblotting and Immunoprecipitations.

Whole cell or cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were extracted as previously described (9) and are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

In Vitro Deubiquitination Assay.

Ubiquitinated p65 was generated by adding purified bacterial recombinant GST-protein to an in vitro ubiquitination assay as previously described (6). Ubiquitinated GST-p65 was affinity purified with glutathione (GSH) agarose, eluted, and immuno-purified using anti-FLAG antibody. Ubiquitinated GST-p65 was added to a deubiquitination reaction (50 mm Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, and 10 mm DTT) with or without purified insect-derived recombinant USP7 (E-519–025 RnD Systems). Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, terminated by the addition of 2× SDS gel loading dye, and analyzed by immunoblot.

NF-κB–Dependent Reporter Gene Assay.

The pNF-κB-luc and pAP1-luc plasmids were obtained from Clontech and pRL-TK from Promega. The IL23p19 reporter plasmids were previously described (29) and are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation.

Cells were treated as indicated and fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min with gentle agitation and chromatin immunoprecipitation,s performed as previously described and as detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Spot synthesis of Peptides and Overlay Analysis.

Nitrocellulose-bound peptide arrays of p65-derived peptides were generated as previously described (34) and are detailed in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Youhai Chen, Daniel Krappmann, and Karen Keeshan for their assistance, and Lienhard Schmitz, Roger Everett, and Guillermina Lozano for reagents. This research was supported by the Science Foundation Ireland (Grant 08/IN.1/B1843 and Centre for Science Engineering and Technology Grant 07/CE/B1368), the Marie Curie International Re-Integration Grant programme, and an R01 DK073639 grant from the National Institutes of Health and a Senior Research Award from Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America (to E.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.G. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1208446110/-/DCSupplemental

References

- 1.Carmody RJ, Chen YH. Nuclear factor-kappaB: Activation and regulation during toll-like receptor signaling. Cell Mol Immunol. 2007;4(1):31–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell. 2008;132(3):344–362. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghosh S, Hayden MS. New regulators of NF-kappaB in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(11):837–848. doi: 10.1038/nri2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wan F, Lenardo MJ. The nuclear signaling of NF-kappaB: Current knowledge, new insights, and future perspectives. Cell Res. 2010;20(1):24–33. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mao X, et al. GCN5 is a required cofactor for a ubiquitin ligase that targets NF-kappaB/RelA. Genes Dev. 2009;23(7):849–861. doi: 10.1101/gad.1748409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryo A, et al. Regulation of NF-kappaB signaling by Pin1-dependent prolyl isomerization and ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of p65/RelA. Mol Cell. 2003;12(6):1413–1426. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka T, Grusby MJ, Kaisho T. PDLIM2-mediated termination of transcription factor NF-kappaB activation by intranuclear sequestration and degradation of the p65 subunit. Nat Immunol. 2007;8(6):584–591. doi: 10.1038/ni1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maine GN, Mao X, Komarck CM, Burstein E. COMMD1 promotes the ubiquitination of NF-kappaB subunits through a cullin-containing ubiquitin ligase. EMBO J. 2007;26(2):436–447. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmody RJ, Ruan Q, Palmer S, Hilliard B, Chen YH. Negative regulation of toll-like receptor signaling by NF-kappaB p50 ubiquitination blockade. Science. 2007;317(5838):675–678. doi: 10.1126/science.1142953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saccani S, Marazzi I, Beg AA, Natoli G. Degradation of promoter-bound p65/RelA is essential for the prompt termination of the nuclear factor kappaB response. J Exp Med. 2004;200(1):107–113. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosisio D, et al. A hyper-dynamic equilibrium between promoter-bound and nucleoplasmic dimers controls NF-kappaB-dependent gene activity. EMBO J. 2006;25(4):798–810. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geng H, Wittwer T, Dittrich-Breiholz O, Kracht M, Schmitz ML. Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB p65 at Ser468 controls its COMMD1-dependent ubiquitination and target gene-specific proteasomal elimination. EMBO Rep. 2009;10(4):381–386. doi: 10.1038/embor.2009.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, et al. Regulation of NF-kappaB activity by competition between RelA acetylation and ubiquitination. Oncogene. 2011;31(5):611–623. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komander D, Clague MJ, Urbé S. Breaking the chains: Structure and function of the deubiquitinases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10(8):550–563. doi: 10.1038/nrm2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frappier L, Verrijzer CP. Gene expression control by protein deubiquitinases. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Everett RD, et al. A novel ubiquitin-specific protease is dynamically associated with the PML nuclear domain and binds to a herpesvirus regulatory protein. EMBO J. 1997;16(7):1519–1530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.7.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Daubeuf S, et al. HSV ICP0 recruits USP7 to modulate TLR-mediated innate response. Blood. 2009;113(14):3264–3275. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li M, et al. Deubiquitination of p53 by HAUSP is an important pathway for p53 stabilization. Nature. 2002;416(6881):648–653. doi: 10.1038/nature737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cummins JM, et al. Tumour suppression: Disruption of HAUSP gene stabilizes p53. Nature. 2004;428(6982):1 p following 486. doi: 10.1038/nature02501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song MS, et al. The deubiquitinylation and localization of PTEN are regulated by a HAUSP-PML network. Nature. 2008;455(7214):813–817. doi: 10.1038/nature07290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maertens GN, El Messaoudi-Aubert S, Elderkin S, Hiom K, Peters G. Ubiquitin-specific proteases 7 and 11 modulate Polycomb regulation of the INK4a tumour suppressor. EMBO J. 2010;29(15):2553–2565. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epping MT, et al. TSPYL5 suppresses p53 levels and function by physical interaction with USP7. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(1):102–108. doi: 10.1038/ncb2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong S, Kim SJ, Ka S, Choi I, Kang S. USP7, a ubiquitin-specific protease, interacts with ataxin-1, the SCA1 gene product. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20(2):298–306. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Horst A, et al. FOXO4 transcriptional activity is regulated by monoubiquitination and USP7/HAUSP. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(10):1064–1073. doi: 10.1038/ncb1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang Z, et al. Deubiquitylase HAUSP stabilizes REST and promotes maintenance of neural progenitor cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(2):142–152. doi: 10.1038/ncb2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell. 2009;138(2):389–403. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colland F, et al. Small-molecule inhibitor of USP7/HAUSP ubiquitin protease stabilizes and activates p53 in cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(8):2286–2295. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawrence T, Bebien M, Liu GY, Nizet V, Karin M. IKKalpha limits macrophage NF-kappaB activation and contributes to the resolution of inflammation. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1138–1143. doi: 10.1038/nature03491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carmody RJ, Ruan Q, Liou HC, Chen YH. Essential roles of c-Rel in TLR-induced IL-23 p19 gene expression in dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2007;178(1):186–191. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hay RT, Nicholson J. DNA binding alters the protease susceptibility of the p50 subunit of NF-kappa B. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21(19):4592–4598. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.19.4592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matthews JR, et al. Conformational changes induced by DNA binding of NF-kappa B. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23(17):3393–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.17.3393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hager GL, McNally JG, Misteli T. Transcription dynamics. Mol Cell. 2009;35(6):741–753. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathas S, Misteli T. The dangers of transcription. Cell. 2009;139(6):1047–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kiely PA, et al. Phosphorylation of RACK1 on tyrosine 52 by c-Abl is required for insulin-like growth factor I-mediated regulation of focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(30):20263–20274. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.017640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.