Abstract

Objective To estimate the risk of pulmonary embolism and venous thromboembolism in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation.

Design Cross sectional study.

Setting Sweden.

Participants 23 498 women who had given birth after in vitro fertilisation between 1990 and 2008 and 116 960 individually matched women with natural pregnancies.

Main outcome measures Risk of pulmonary embolism and venous thromboembolism (identified by linkage to the Swedish national patient register) during the whole pregnancy and by trimester.

Results Venous thromboembolism occurred in 4.2/1000 women (n=99) after in vitro fertilisation compared with 2.5/1000 (n=291) in women with natural pregnancies (hazard ratio 1.77, 95% confidence interval 1.41 to 2.23). The risk of venous thromboembolism was increased during the whole pregnancy (P<0.001) and differed between the trimesters (P=0.002). The risk was particularly increased during the first trimester, at 1.5/1000 after in vitro fertilisation versus 0.3/1000 (hazard ratio 4.22, 2.46 to 7.26). The proportion of women experiencing pulmonary embolism during the first trimester was 3.0/10 000 after in vitro fertilisation versus 0.4/10 000 (hazard ratio 6.97, 2.21 to 21.96).

Conclusions In vitro fertilisation is associated with an increased risk of pulmonary embolism and venous thromboembolism during the first trimester. The risk of pulmonary embolism is low in absolute terms but because the condition is a leading cause of maternal mortality and clinical suspicion is critical for diagnosis, an awareness of this risk is important.

Trial registration ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01524393.

Introduction

Infertility affects more than 10% of couples worldwide.1 Since the birth of the first “test tube baby” in 1978, in vitro fertilisation has been used increasingly to assist reproduction.2 To date about five million people have been born after in vitro fertilisation and this method is regarded as an effective and safe technique, with about a third of attempts resulting in pregnancy and a quarter in live births.3 4

It is well known that the risk of venous thromboembolism is increased during normal pregnancy. According to data from Sweden and Norway during the early 1990s venous thromboembolism occurred in slightly more than one out of 1000 pregnant women.5 6 Venous thromboembolism in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation has been reported in numerous case reports and in two small consecutive series, two out of 2500 (0.8/1000)7 women and three out of 2748 (1.1/1000) women.8 Notably, these estimates of incidence have been claimed to be comparable to those during natural pregnancy.9 A recent report suggested that the incidence of venous thromboembolism after in vitro fertilisation was substantially increased during the first trimester but not in the other two trimesters.10 No information exists on the risk of pulmonary embolism after in vitro fertilisation, which is important because embolism is a leading cause of maternal mortality.11 12 Moreover, in the recently published report outpatient diagnoses were not included and no adjustments were made for the increased incidence of venous thromboembolism during the past decade.10 Furthermore, no adjustments were made for the reported age difference in cases and controls, making the strength of the risk estimate of a 10-fold increase during the first trimester less exact.

We compared the risk of pulmonary embolism and venous thromboembolism in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation with that of age and time matched women with natural pregnancy.

Methods

This cross sectional study was based on the Swedish population between 1990 and 2008, with linkage of data from two national registers. The Swedish national patient register encompasses both inpatients and outpatients.13 Inpatient data in Sweden became available nationwide in 1987. Outpatient diagnoses from hospitals started to be collected in 1997. Data in the patient register can be linked to other registries through the unique personal identity number assigned to Swedish residents.14

Women who underwent in vitro fertilisation

From the Swedish in vitro fertilisation register at the National Board of Health and Welfare we retrieved information on mothers who had given birth after in vitro fertilisation. This register is now part of the Swedish medical birth register at the National Board of Health and Welfare and includes information on pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation since 1982. The birth register includes data that were collected and registered at the time the women were pregnant and includes validated information on the pregnancy, delivery, and neonatal periods for more than 99% of births in Sweden since 1973.15 The birth register does not, however, include data on miscarriages or other pregnancy losses.

We restricted data retrieval to mothers of children born from 1990 and whose first child was born after assisted reproduction by in vitro fertilisation. Subsequent pregnancies in these women were therefore excluded from the study. Thus we identified 23 498 women who had given birth to their first child after in vitro fertilisation between 1990 and 2008.

Women who did not undergo in vitro fertilisation

From the medical birth register each woman who had undergone in vitro fertilisation was matched with up to five women whose first child was born without in vitro fertilisation by calendar year of delivery (two years either way) and maternal age (one year either way). Subsequent pregnancies in these women were excluded from the study; the analysis therefore included only one pregnancy per patient. The matching resulted in 116 960 women who did not undergo in vitro fertilisation.

From the medical birth register we retrieved information on the women’s country of birth, body mass index before pregnancy, marital status, smoking status, number of older siblings, singleton or multiple births, and estimated length of gestation. We calculated the dates of the trimesters from the length of gestation. The women’s level of educational attainment was obtained from the register of education, Statistics Sweden, by record linkage.14

We obtained information on the diagnoses of venous thromboembolism including pulmonary embolism by linkage to the Swedish patient register.13 The register comprises date of admission and discharge and the main diagnosis, with up to seven concomitant diagnoses. Inpatient care has been recorded nationwide since 1987. Outpatient visits at specialist clinics are included from 1997. Diagnoses were recorded according to the International Classification of Diseases (ninth revision before 1996 and 10th revision from 1997): codes 415B, 451B, 452, 453C-D, 453W, 453X, 673C, 671D-E, and 671F in ICD9 and I260, I269, I801-3, I808-9, I822-3, I828-9, O223, O225, O871, O873, O879, and O882 in ICD10. We therefore included all possible diagnoses of venous thromboembolism irrespective of location.

Statistical analysis

The risk of venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism was assessed in women who had and had not undergone in vitro fertilisation during three periods: from 1 January 1987 to the calculated date of start of pregnancy, during pregnancy and delivery plus 42 days, and from day 43 to day 365 after delivery. We calculated proportional hazard regression on time to first event. To model and test the effect of in vitro fertilisation on venous thromboembolism in the different trimesters and delivery we used time dependent proportional hazard regression. We calculated 95% confidence intervals. In the time dependent model we tested effect modification of body mass index on the effect of in vitro fertilisation. Multivariate analysis taking parity, single or multiple births, smoking, education, maternal age, country of birth, calendar period, and marital status into account was carried out on the material stratified on body mass index and restricted to women with a body mass index <30.

All statistical calculations were done using SAS software, version 9.3. The regressions were carried out in the proportional hazards regression (PHREG) procedure of SAS.

Results

Overall, 23 498 women were identified who had given birth after in vitro fertilisation. The median age of these mothers was 33 (interquartile range 31-36) years. Matching with women who had not had in vitro fertilisation resulted in an almost identical age distribution (median 33 (31-36) years, table 1). The proportion of multiple births in the women who had undergone in vitro fertilisation was 16.9%. Of the women who had had in vitro fertilisation about 86% were born in Sweden, 6.7% were smokers, 53.2% had a body mass index <25, 8.1% were obese (body mass index >30), and 47.1% had attained university level education (>12 years).

Table 1.

Characteristics of pregnant women who underwent in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and women with natural pregnancies between 1990 and 2008, Sweden. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Characteristics | IVF pregnancies (n=23 498) | Natural pregnancies (n=116 960) |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal age at birth: | ||

| 19-24 | 322 (1.4) | 1510 (1.3) |

| 25-29 | 3764 (16.0) | 18 438 (15.8) |

| 30-34 | 10 129 (43.1) | 50 575 (43.2) |

| 35-39 | 8016 (34.1) | 40 083 (34.3) |

| 40-47 | 1267 (5.4) | 6354 (5.4) |

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 33.3 (4.0) | 33.4 (3.9) |

| Median (interquartile range) age (years) | 33 (31-36) | 33 (31-36) |

| Born in Sweden | 20 267 (86.2) | 95 180 (81.4) |

| Prepregnancy body mass index: | ||

| Missing data | 3961 (16.9) | 20 228 (17.3) |

| <25 | 12 490 (53.2) | 62 464 (53.4) |

| 25-29 | 5136 (21.9) | 24 646 (21.1) |

| ≥30 | 1911 (8.1) | 9622 (8.2) |

| Cigarette smoker: | ||

| Missing data | 1793 (7.6) | 7731 (6.6) |

| No | 20 130 (85.7) | 96 996 (82.9) |

| Yes | 1575 (6.7) | 12 233 (10.5) |

| Education (years): | ||

| Missing data | 48 (0.2) | 1027 (0.9) |

| ≤9 | 1789 (7.6) | 11 741 (10.0) |

| 10-12 | 10 588 (45.1) | 50 527 (43.2) |

| >12 | 11 073 (47.1) | 53 665 (45.9) |

| Marital status: | ||

| Missing data | 1800 (7.7) | 7798 (6.7) |

| Married to or cohabiting with father of child | 21 569 (91.8) | 103 882 (88.8) |

| Single | 51 (0.2) | 3,166 (2.7) |

| Other | 78 (0.3) | 2114 (1.8) |

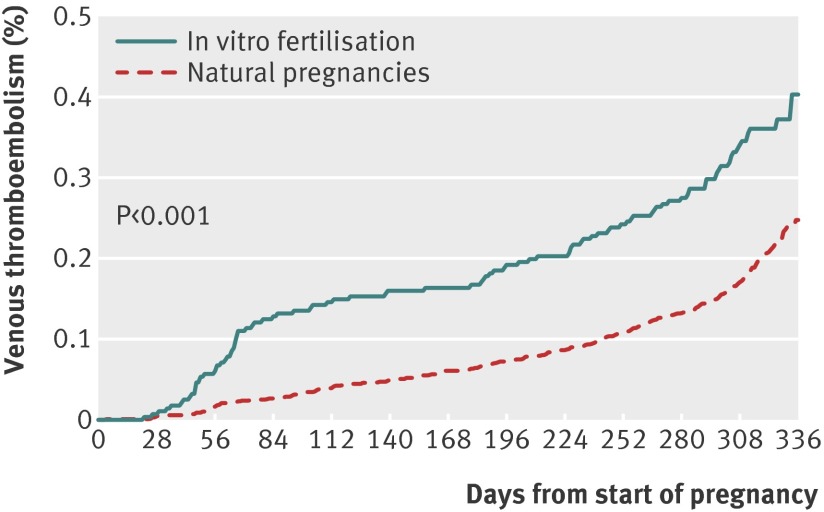

The proportion of women who underwent in vitro fertilisation and experienced venous thromboembolism was 4.2/1000 (n=99) compared with 2.5/1000 (n=291) of the 116 960 matched women (table 2). The risk after in vitro fertilisation increased during the whole pregnancy (P<0.001; hazard ratio 1.77, 95% confidence interval 1.41 to 2.23) and differed between the trimesters (P=0.002, fig 1 and table 3). In particular the risk was increased during the first trimester (1.5/1000 v 0.3/1000, hazard ratio 4.05, 2.54 to 6.46). The risk did not differ between the two groups of women before pregnancy (hazard ratio 0.85, 0.66 to 1.10) and during the year after delivery (1.29, 0.82 to 2.02, table 2).

Table 2.

Venous thromboembolism and pulmonary embolism events in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and women with natural pregnancies matched on age and calendar period of delivery. Values are numbers (percentages) of women unless stated otherwise

| Events in relation to pregnancy | IVF pregnancies (n=23 498) | Natural pregnancies (n=116 960) | Proportional hazard regression (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venous thromboembolism: | |||

| Prepregnancy | 71 (0.30) | 415 (0.35) | 0.85 (0.66 to 1.10) |

| Pregnancy and delivery | 99 (0.42) | 291 (0.25) | 1.77 (1.41 to 2.23) |

| Days 43-365 postpartum | 24 (0.10) | 95 (0.08) | 1.29 (0.82 to 2.02) |

| Pulmonary embolism: | |||

| Prepregnancy | 21 (0.09) | 103 (0.09) | 1.04 (0.65 to 1.66) |

| Pregnancy and delivery | 19 (0.08) | 70 (0.06) | 1.42 (0.86 to 2.36) |

| Days 43-365 days postpartum | 3 (0.01) | 26 (0.02) | 0.60 (0.18 to 1.98) |

Fig 1 Proportional hazard regression of venous thromboembolism in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation (n=23 498) and in women with natural pregnancies (n=11 960) matched on age and calendar period of delivery

Table 3.

Time to first venous thromboembolic event by trimester in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and women with natural pregnancies matched on age and calendar period of delivery. Effect of different levels of effect modifier body mass index (BMI) is also given. Values are numbers (percentages) of women unless stated otherwise

| Variables | IVF pregnancies (n=23 498) | Natural pregnancies (n=116 960) | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | Proportional hazard regression (95% CI)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | BMI <25 | BMI 25-29.9 | BMI >30 | ||||

| First trimester (weeks 1-12) | 36 (0.15) | 38 (0.03) | 4.61 (2.95 to 7.21) | 4.05 (2.54 to 6.46) | 6.64 (3.6 to 12.23) | 2.61 (0.97 to 7.07) | 1.01 (0.22 to 4.6) |

| Second trimester (weeks 13-25) | 23 (0.10) | 63 (0.05) | 1.00 (0.51 to 1.97) | 1.11 (0.54 to 2.29) | 1.04 (0.40 to 2.72) | 2.13 (0.66 to 6.93) | —† |

| Third trimester (week 26 to <3 days before birth) | 33 (0.14) | 94 (0.08) | 1.04 (0.64 to 1.69) | 1.30 (0.77 to 2.19) | 1.30 (0.61 to 2.80) | 1.80 (0.81 to 4.01) | 0.26 (0.04 to 1.91) |

| ≤3 days before to 42 days after birth | 49 (0.21) | 192 (0.16) | 1.69 (1.15 to 2.48) | 1.59 (1.03 to 2.45) | 1.66 (0.90 to 3.05) | 1.55 (0.75 to 3.24) | 1.45 (0.49 to 4.27) |

| P value for test of difference‡ | — | — | — | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.07 | 0.53 |

| P value for test of equal effect in all time periods§ | — | — | — | 0.002 | 0.0006 | 0.86 | 0.33 |

*Women with complete data on BMI.

†Weeks 13-25 are merged with week 26 until three days before delivery owing to few events.

‡Wald χ2 test for difference between IVF and no IVF.

§Wald χ2.

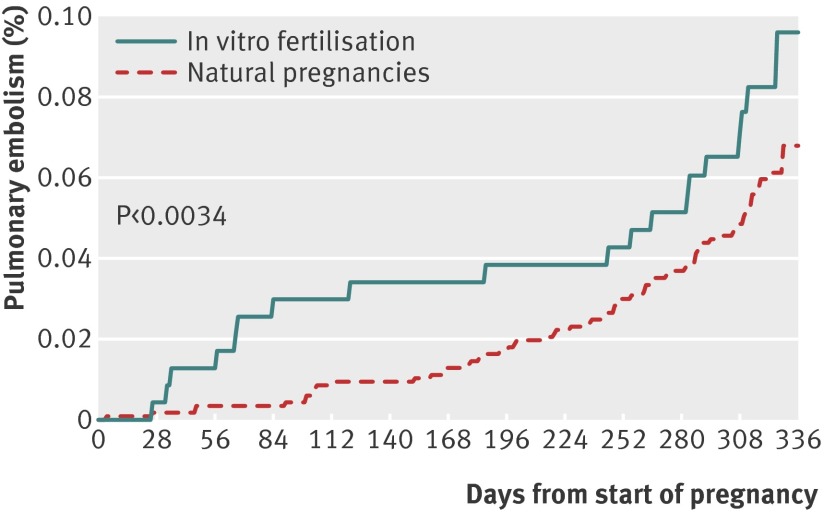

Pulmonary embolism occurred in 19 women who underwent in vitro fertilisation (8.1/10 000) compared with 70 of the 116 960 matched women (6.0/10 000). The risk was increased after in vitro fertilisation (P<0.0034; hazard ratio 1.42, 0.86 to 2.36, fig 2 and table 4) and differed between the trimesters (P=0.0092). In particular the risk was increased during the first trimester (3.0/10 000 v 0.4/10 000, 6.97, 2.21 to 21.96).

Fig 2 Proportional hazard regression of pulmonary embolism in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation (n=23 498) and in women with natural pregnancies (n=11 960) matched on age and calendar period of delivery

Table 4.

Time to first event of pulmonary embolism during trimesters in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and women with natural pregnancies matched on age and calendar period of delivery. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Variables | IVF pregnancies (n=23 498) | Natural pregnancies (n=116 960) | Proportional hazard regression (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| First trimester (weeks 1-12) | 7 (0.03) | 5 (0.004) | 6.97 (2.21 to 21.96) |

| Second trimester (weeks 13-25) | 5 (0.02) | 13 (0.01) | 0.42 (0.05 to 3.20) |

| Third trimester (week 26 to <3 days before birth) | 6 (0.03) | 18 (0.02) | 0.40 (0.10 to 1.68) |

| ≤3 days before to 42 days after birth | 11 (0.05) | 49 (0.04) | 1.79 (0.86 to 3.74) |

| P value for test of difference* | — | — | 0.0034 |

| Test of equal effect in all time periods† | — | — | 0.0092 |

*Wald χ2 for difference between IVF and no IVF.

†Wald χ2 test.

Figure 3 shows the time trend of diagnoses. The incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy in women who did not undergo in vitro fertilisation was comparable to that of women in Sweden and Norway during the 1990s.5 6 However, the incidence increased during the first decade of the new millennium, although it seemed mainly confined to outpatients.

Fig 3 Time trends of incidence of registered venous thromboembolic (VTE) diagnoses per 1000 pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation and women with natural pregnancies matched on age and calendar period of delivery in Swedish national patient register, National Board of Health and Welfare

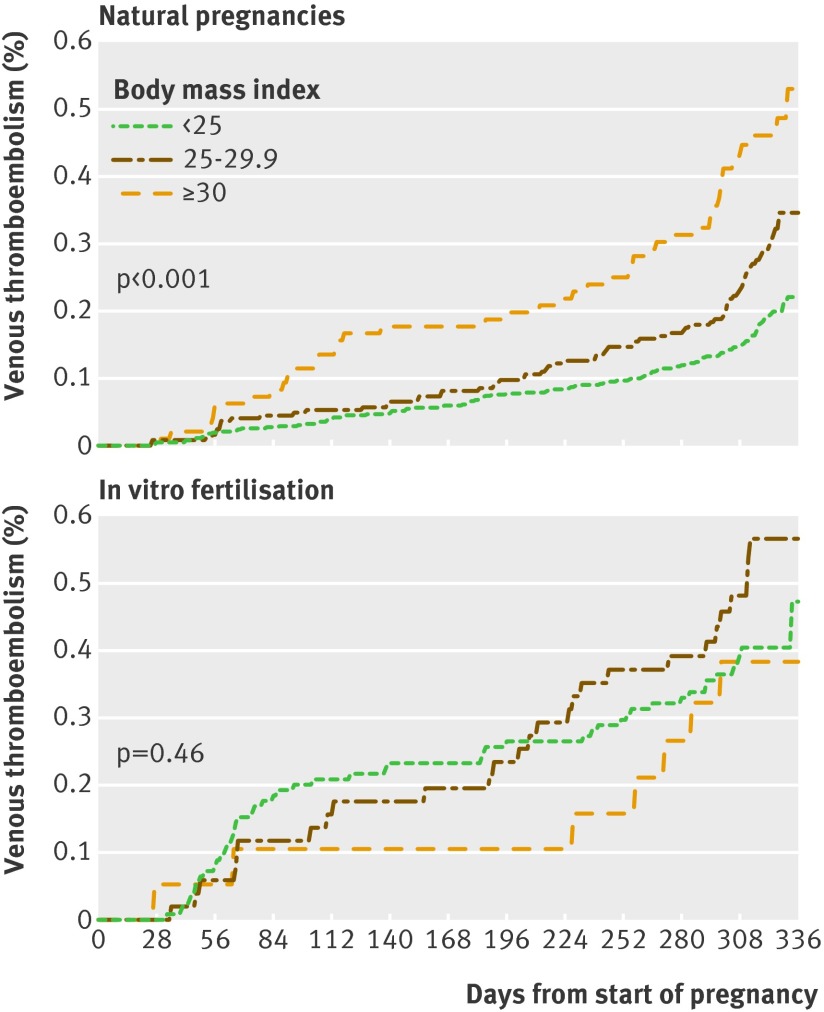

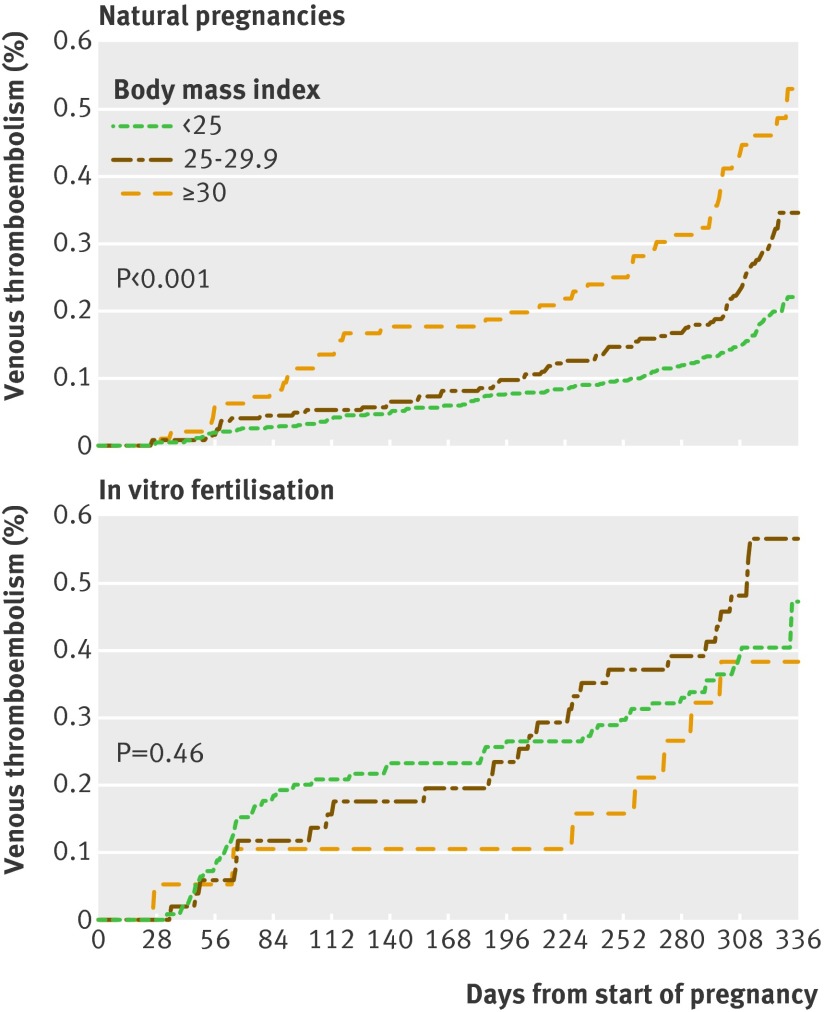

No significant interaction was observed between body mass index and in vitro fertilisation on incidence of venous thromboembolism (P=0.21). The incidence in women who did not undergo in vitro fertilisation, however, increased as expected by body mass index (P<0.001), but no such effect was observed in women after in vitro fertilisation (P=0.46, fig 4).

Fig 4 Proportional hazard regression of venous thromboembolism in three strata for body mass index (<25, 25-29.9, and ≥30) in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation (n=23 498) and in women with natural pregnancies (n=116 960) matched on age and calendar period of delivery

Further multivariate analysis taking calendar period, parity, single or multiple births, smoking, education, maternal age, country of birth, and marital status into account was carried out stratified on body mass index in two categories: <25 and 25-29.9 (table 5). Adjustment did not alter the significance of the main finding. The adjusted hazard ratio of venous thromboembolism during the first trimester was 4.22 (95% confidence interval 2.46 to 7.26). Multiple births seemed to have an influence on incidence of venous thromboembolism (adjusted hazard ratio 2.12, 1.38 to 3.28).

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis stratified on body mass index (BMI) in pregnant women with BMI <30: 23 498 women after in vitro fertilisation (IVF) and 116 960 women with natural pregnancies matched on age and calendar period of delivery

| Variables | Hazard ratio (95 % CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI <25 | BMI 25-29.9 | Adjusted by conditioning on BMI | |

| Natural pregnancies | 1=reference | 1=reference | 1=reference |

| IVF pregnancies: | |||

| First trimester (weeks 1-12) | 5.21 (2.68 to 10.14) | 2.40 (0.85 to 6.80) | 4.13 (2.37 to 7.17) |

| Second trimester (weeks 13-25) | 0.91 (0.34 to 2.46) | 1.78 (0.53 to 5.93) | 1.18 (0.55 to 2.51) |

| Third trimester (week 26 to <3 days before birth) | 1.17 (0.53 to 2.58) | 1.38 (0.57 to 3.33) | 1.25 (0.69 to 2.25) |

| ≤3 days before to 42 days after birth | 1.10 (0.56 to 2.17) | 1.27 (0.59 to 2.75) | 1.16 (0.69 to 1.93) |

| P value for test of difference* | <0.001 | 0.77 | <0.001 |

| Test of equal effect in all time periods† | 0.001 | 0.42 | 0.0017 |

| No of older siblings: | |||

| None | 1=reference | 1=reference | — |

| ≥1 | 0.92 (0.65 to 1.30) | 1.36 (0.58 to 3.19) | 0.83 (0.63 to 1.1) |

| Single birth | 1=reference | 1=reference | |

| Multiple births | 2.52 (1.49 to 4.25) | 1.33 (0.57 to 3.13) | 2.06 (1.32 to 3.21) |

| Smoking at start of pregnancy: | |||

| No | 1=reference | 1=reference | — |

| Yes | 0.91 (0.49 to 1.68) | 0.89 (0.45 to 1.77) | 0.89 (0.56 to 1.41) |

| Education (years): | |||

| ≤9 | 1=reference | 1=reference | — |

| 10-12 | 1.16 (0.57 to 2.39) | 0.55 (0.27 to 1.12) | 0.88 (0.53 to 1.44) |

| >12 | 1.26 (0.61 to 2.59) | 0.80 (0.40 to 1.62) | 1.06 (0.64 to 1.75) |

| Maternal age at delivery (years): | |||

| <35 | 1=reference | 1=reference | — |

| ≥35 | |||

| First trimester (weeks 1-12) | 0.84 (0.43 to 1.63) | 2.34 (0.85 to 6.45) | 1.14 (0.67 to 1.96) |

| Second trimester (weeks 13-25) | 0.60(0.25 to 1.43) | 2.25 (0.73 to 6.88) | 0.92 (0.48 to 1.75) |

| Third trimester (week 26 to <3 before birth) | 0.60(0.30 to 1.23) | 1.20 (0.58 to 2.49) | 0.84 (0.51 to 1.38) |

| ≤3 before to 42 days after birth | 1.53 (0.91 to 2.57) | 2.64 (1.41 to 4.96) | 1.88 (1.26 to 2.78) |

| Country of birth: | |||

| Sweden | 1=reference | — | — |

| Other country | 1.14 (0.72 to 1.83) | 3.06 (1.45 to 6.44) | 1.62 (1.09 to 2.41) |

| Calendar period: | |||

| 1990-2001 | 1=reference | 1=reference | 1=reference |

| 2002-08 | 1.55 (1.12 to 2.14) | 2.64 (1.64 to 4.25) | 1.86 (1.43 to 2.43) |

| Marital status: | |||

| Married to or cohabiting with father of child | 1=reference | 1=reference | 1=reference |

| Other | 0.81 (0.29 to 2.21) | 1.34 (0.53 to 3.36) | 1.03 (0.52 to 2.03) |

*Wald χ2 for difference between IVF and no IVF.

†Wald χ2.

A separate multivariate analysis on women with first births after in vitro fertilisation compared with women not requiring assisted reproduction resulted in a hazard ratio of 1.64 (1.23 to 2.18) during the whole pregnancy and 3.50 (1.81 to 6.80) during the first trimester. The overall risk during 2001-08 compared with 1990-2001 did not decrease (table 5).

Discussion

Pregnant women are at higher risk of venous thromboembolism after in vitro fertilisation, particularly during the first trimester. The risk of pulmonary embolism in women after in vitro fertilisation was increased almost sevenfold during the first trimester, although the absolute risk was low (2-3 additional cases of pulmonary embolism per 10 000 pregnancies). Pulmonary embolism is, however, an elusive condition that is difficult to diagnose and is a leading cause of maternal death.11 12 Our finding is therefore important to health professionals dealing with women who are recently pregnant after in vitro fertilisation.

The medical literature contains numerous case reports of venous thromboembolism during pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation, and these articles have been reviewed repeatedly.7 9 16 One reason why these case reports attract attention is the unusual sites of the thromboses, such as the arms or neck. These reviews concluded that the risk of venous thromboembolism after in vitro fertilisation is comparable to that of pregnancies after natural conception,9 different to our findings. In our study the incidence of venous thromboembolism in women after in vitro fertilisation significantly increased during the whole pregnancy and differed between the trimesters, in particular during the first trimester. This finding in the first trimester is in line with a recently published study.10 However, the risk estimate in that study was almost double that of the present study—around 10-fold compared with fivefold. This difference in risk estimates probably resulted from the absence of matching by calendar period. From the Swedish medical birth register we matched each woman who had undergone in vitro fertilisation with five women who had not by both calendar period and age. Matching by age is important as women with pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation are on average older than those with natural pregnancies.10 It is well known that the incidence of thromboembolism increases with age.17 We also matched by calendar year of delivery, which avoided biased estimates as the number of pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation and the number of thromboembolic events both increase by calendar year. The in vitro fertilisation procedure has changed over time with the introduction of more patient friendly protocols, less vigorous stimulation with lower doses of gonadotropins and, particularly in Sweden, a decreasing rate of multiple births, from almost 30% to 5%.15 Adjustments were also needed to take account of the increased incidence of venous thromboembolism noted recently.10 We analysed and adjusted for several maternal factors known to affect pregnancy and vascular disease outcome such as age, calendar year of delivery, body mass index, parity, smoking, country of birth, marital status, and education. The risk of venous thromboembolism increased by body mass index in women who did not undergo in vitro fertilisation but not in those who did (fig 4). The reason for this could not be explained. It could be speculated that differing oestrogen levels in lean and obese women might play a part. Furthermore, the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is more common in women with a low body mass index.18 19 Since the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is closely related to venous thromboembolism this might also play a part.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The patient register is generally considered to have high validity and was used to estimate the incidence of venous thromboembolism in pregnant women during 1990-93.4 13 In the present study we found a similar incidence in women who did not undergo in vitro fertilisation during that period. However, thromboembolic events in women regardless of whether they underwent in vitro fertilisation increased during the first decade of the new millennium. One reason for this could be the inclusion of outpatient diagnoses (fig 3). In addition, awareness of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy has increased over time. A high baseline index for suspicion of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy is critical for diagnosis because many of the clinical signs and symptoms are also common in normal pregnancies.20 21 Improvement in diagnostic procedures, including a more extensive use of ultrasound examinations, has probably contributed to the increased incidence of venous thromboembolism.20 22 23 We have no information on the severity of the venous thromboembolic events. Furthermore, improvements in diagnostic procedures and increased doctors’ awareness could contribute to the increased incidence of venous thromboembolism.24 A limitation of our study is that owing to a lack of relevant data we could not check these assumptions.

A further limitation is that we cannot rule out surveillance bias (detection bias) between the two groups of women. Surveillance bias is unlikely, however, because of the noticeable significant increase of thromboembolic events during the first trimester in pregnancies after in vitro fertilisation. A further argument against surveillance bias was the absence of an increased risk after delivery.

A weakness of the Swedish medical birth register is that it only includes women with deliveries. Thus an obvious bias is that more complicated pregnancies resulting in fatal outcomes to the mothers were not included. This could underestimate the true risk of venous thromboembolism and, in particular, pulmonary embolism during a pregnancy after in vitro fertilisation. Notably a major cause of maternal deaths during pregnancy is embolism.11 12 Furthermore, the use of matched controls in the present study clearly indicated an increased risk of thromboembolism after in vitro fertilisation.

A further potential weakness could be an influence of parity on the propensity to acquire thromboses. However, this is opposed by the fact that also women with first births had an increased risk of venous thromboembolism compared with natural pregnancy. Another bias could be the presence of thrombophilia and the antiphospholipid syndrome as these might influence fertility.25 26

Time distribution of thromboembolic events

The distribution of pulmonary embolism and venous thromboembolism during the three trimesters after in vitro fertilisation (figs 1 and 2) contrasted with that of natural pregnancies.17 Notably, the risk of pulmonary embolism in natural pregnancies is highest in the postpartum period,17 20 27 whereas in the present study the greatest risk in women after in vitro fertilisation was during the first trimester. The close time relation to the in vitro fertilisation procedure suggests that changes induced by the procedure itself could be of pathophysiological importance. A plausible initiator of adverse mechanisms could be the noticeable increase in endogenous oestrogen levels during the stimulation phase of treatment before the actual procedure.7 During in vitro fertilisation the oestrogen level increases rapidly (10-fold to 100-fold) from the down-regulation phase to the stimulation phase.28 Exogenous oestrogens have been repeatedly associated with an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism, irrespective of the indication for their use. The first reports were in women using oral contraceptives containing oestrogen and recently in women using oestrogen after the menopause.29 30 31 In the largest randomised study to date the risk of venous thromboembolism in women using exogenous oestrogens compared with placebo was doubled (hazard ratio 2.06, 95% confidence interval 1.57 to 2.70).31 An increased risk of cardiovascular events has also been shown in men receiving oestrogen for testosterone dependent prostatic carcinoma.32

Conclusions

Our results show an increased risk of thromboembolism and, importantly, pulmonary embolism in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation. Doctors should be aware of these increased risks because the symptoms of pulmonary embolism can be insidious and the condition is potentially fatal. Efforts should focus on the identification of women at risk of thromboembolism, with prophylactic anticoagulation considered in women planning to undergo in vitro fertilisation.

What is already known on this topic

Embolism is an important cause of maternal mortality in developed countries

In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is increasingly used for assisted reproduction

Reports suggest that the risk of venous thromboembolism is not increased after IVF compared with natural pregnancies although a recent report showed an increased risk during the first trimester

What this study adds

The risk of venous thromboembolism increased during all trimesters in women after IVF, in particular during the first trimester

The risk of pulmonary embolism significantly increased during the first trimester

Contributors: PH, EW, and OH initiated the study. PH and AE had overall responsibility for the study and are the guarantors. All authors contributed to the study design. AE, EW, LB, and PH contributed to data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. PH led the writing of the report and wrote the first draft of the final report. All authors helped to prepare the final report and have seen and approved the final version. The corresponding author had full access to all data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding: This study was funded through a regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet, the Swedish Research Council, and Karolinska Institutet. The sponsors of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; and no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the research ethics committee of Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden (Dnr 2010/267-31/4).

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2013;346:e8632

References

- 1.Van Voorhis BJ. Clinical practice. In vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med 2007;356:379-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steptoe PC, Edwards RG. Birth after the reimplantation of a human embryo. Lancet 1978;2:366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet. Human in vitro fertilization, 2010. http://static.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/2010/adv.pdf.

- 4.Malizia BA, Hacker MR, Penzias AS. Cumulative live-birth rates after in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med 2009;360:236-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindqvist P, Dahlback B, Marsal K. Thrombotic risk during pregnancy: a population study. Obstet Gynecol 1999;94:595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobsen AF, Skjeldestad FE, Sandset PM. Incidence and risk patterns of venous thromboembolism in pregnancy and puerperium—a register-based case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;198:233 e1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan WS, Ginsberg JS. A review of upper extremity deep vein thrombosis in pregnancy: unmasking the ‘ART’ behind the clot. J Thromb Haemost 2006;4:1673-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mara M, Koryntova D, Rezabek K, Kapral A, Drbohlav P, Jirsova S, et al. [Thromboembolic complications in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization: retrospective clinical study]. Ceska Gynekol 2004;69:312-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan WS, Dixon ME. The “ART” of thromboembolism: a review of assisted reproductive technology and thromboembolic complications. Thromb Res 2008;121:713-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rova K, Passmark H, Lindqvist PG. Venous thromboembolism in relation to in vitro fertilization: an approach to determining the incidence and increase in risk in successful cycles. Fertil Steril 2012;97:95-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang J, Elam-Evans LD, Berg CJ, Herndon J, Flowers L, Seed KA, et al. Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance—United States, 1991—1999. MMWR Surveill Summ 2003;52:1-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Herbst MA, Meyers JA, Hankins GD. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:36 e1-5; discussion 91-2 e7-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Board of Health and Welfare. The National Patient Register, 2011. www.socialstyrelsen.se/register/halsodataregister/patientregistret/inenglish.

- 14.Ludvigsson JF, Otterblad-Olausson P, Pettersson BU, Ekbom A. The Swedish personal identity number: possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur J Epidemiol 2009;24:659-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Board of Health and Welfare. The Swedish medical birth register: a summary of content and quality, 2011. 2012. www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/10655/2003-112-3_20031123.pdf.

- 16.Chan WS. The ‘ART’ of thrombosis: a review of arterial and venous thrombosis in assisted reproductive technology. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2009;21:207-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heit JA, Kobbervig CE, James AH, Petterson TM, Bailey KR, Melton LJ, 3rd. Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:697-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Navot D, Relou A, Birkenfeld A, Rabinowitz R, Brzezinski A, Margalioth EJ. Risk factors and prognostic variables in the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988;159:210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril 2008;90(5 Suppl):S188-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marik PE, Plante LA. Venous thromboembolic disease and pregnancy. N Engl J Med 2008;359:2025-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg VA, Lockwood CJ. Thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2007;34:481-500, xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wells PS, Hirsh J, Anderson DR, Lensing AW, Foster G, Kearon C, et al. Accuracy of clinical assessment of deep-vein thrombosis. Lancet 1995;345:1326-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells PS, Anderson DR, Rodger M, Forgie M, Kearon C, Dreyer J, et al. Evaluation of D-dimer in the diagnosis of suspected deep-vein thrombosis. N Engl J Med 2003;349:1227-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cutts BA, Dasgupta D, Hunt BJ. New directions in the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2012; published online 20 Jun. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Sauer R, Roussev R, Jeyendran RS, Coulam CB. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies among women experiencing unexplained infertility and recurrent implantation failure. Fertil Steril 2010;93:2441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coulam CB, Jeyendran RS. Thrombophilic gene polymorphisms are risk factors for unexplained infertility. Fertil Steril 2009;91(4 Suppl):1516-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leung AN, Bull TM, Jaeschke R, Lockwood CJ, Boiselle PM, Hurwitz LM, et al. American Thoracic Society Documents: an official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology clinical practice guideline—evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Radiology 2012;262:635-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Westerlund E, Antovic A, Hovatta O, Eberg KP, Blomback M, Wallen H, et al. Changes in von Willebrand factor and ADAMTS13 during IVF. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2011;22:127-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stadel BV. Oral contraceptives and cardiovascular disease (second of two parts). N Engl J Med 1981;305:672-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grady D, Wenger NK, Herrington D, Khan S, Furberg C, Hunninghake D, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy increases risk for venous thromboembolic disease. The Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:689-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cushman M, Kuller LH, Prentice R, Rodabough RJ, Psaty BM, Stafford RS, et al. Estrogen plus progestin and risk of venous thrombosis. JAMA 2004;292:1573-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henriksson P, Edhag O. Orchidectomy versus oestrogen for prostatic cancer: cardiovascular effects. BMJ 1986;293:413-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]