Abstract

Based on our prior antitumor hits, 32 novel N-alkyl-N-substituted phenylpyridin-2-amine derivatives were designed, synthesized and evaluated for cytotoxic activity against A549, KB, KBVIN, and DU145 human tumor cell lines (HTCL). Subsequently, three new leads (6a, 7g, and 8c) with submicromolar GI50 values of 0.19 to 0.41 μM in the cellular assays were discovered, and these compounds also significantly inhibited tubulin assembly (IC50 1.4–1.7 μM) and competitively inhibited colchicine binding to tubulin with effects similar to those of the clinical candidate CA-4 in the same assays. These promising results indicate that these tertiary diarylamine derivatives represent a novel class of tubulin polymerization inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site and showing significant anti-proliferative activity.

Keywords: N-alkyl-N-phenylpyridin-2-amines, cytotoxicity, tubulin polymerization inhibitors, colchicine binding site

Introduction

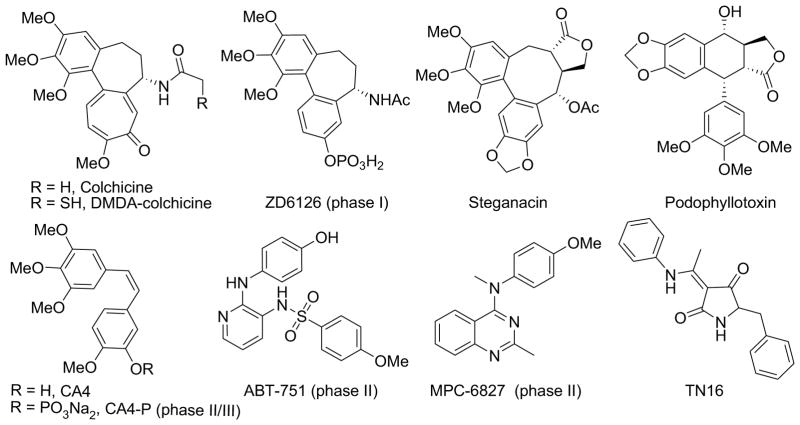

Microtubules are formed by polymerization of heterodimers of α- and β-tubulin, and play important roles in cellular activities, including cell structure maintenance, intracellular transport, mitosis, and cell division. Taxoids and vincristine alkaloids are two well-known classes of anticancer drugs that act as tubulin inhibitors by targeting two distinct binding sites (i.e., taxol and vinca sites) on the α,β-tubulin heterodimer1,2 and disrupting the dynamics of microtubule assembly and disassembly. They are effective in the clinical treatment of cancers, but do have certain deficiencies, including narrow therapeutic indexes and emergence of drug resistance. In efforts to overcome these drawbacks, many new tubulin inhibitors, which are targeted at the colchicine site, a third distinct binding site on tubulin, have been discovered recently and are the subjects of intense investigation. Figure 1 shows examples of such inhibitors, including plant natural products and derivatives, as well as synthetic small molecules. Because of their synthetic accessibility and structural diversity, certain small molecule drug candidates. such as CA-4, ABT-751, and MPC-6827, are currently undergoing clinical trials for treating cancers. These results greatly encourage further efforts to design and discover novel small molecules that function as tubulin polymerization inhibitors targeted at the colchicine binding site.

Figure 1.

Plant natural products, derivatives, and synthetic compounds as tubulin inhibitors targeted at the colchicine binding site. Some of them are in clinical trials.

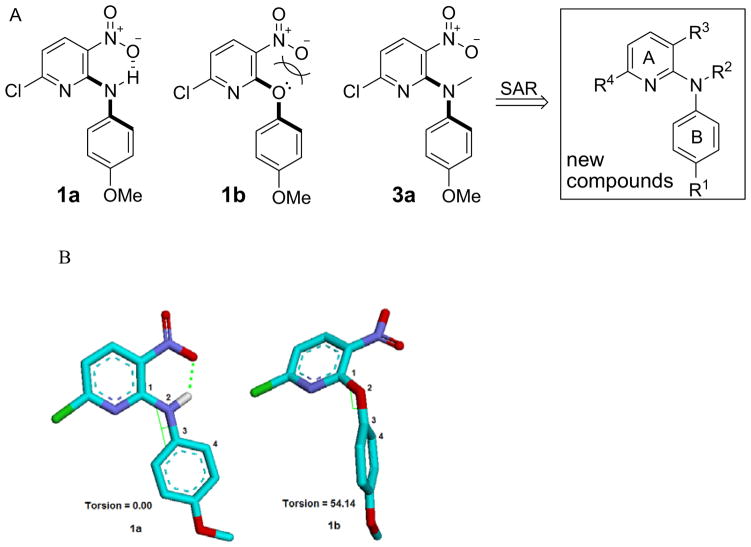

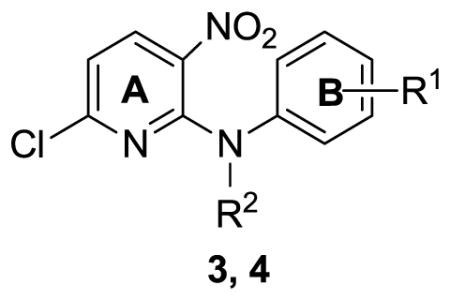

In our prior studies, we discovered two synthetic hits 6-chloro-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)- 3-nitropyridin-2-amine (1a) and 6-chloro-2-(4-methoxyphenoxy)-3-nitro pyridine (1b) by using cell assay screening. They showed promising cytotoxic activity (GI50 values 2.40–13.5 μM and 1.18–2.03 μM, respectively) against a panel of human tumor cell lines (HTCL), including A549, KB, KBVIN, and DU145.3 While the only structural difference between 1a and 1b is the linker (NH or O) between the two aryl rings (A and B rings), 1b was two- to seven-fold more potent than 1a. Therefore, we postulated that the linker might be associated with the molecular antitumor potency. By performing a conformation analysis using a molecular mechanics (MM2) method with energy minimization and dynamics calculation,4 we found that the phenyl and pyridine rings of compounds 1a and 1b have quite different spatial orientations as shown in Figure 2. Compound 1a has a conjugated resonance system and a planar conformation, in which an intramolecular hydrogen bond between the hydrogen of the NH linker and an oxygen atom of the ortho-nitrogen group orients the phenyl and pyridine rings (A and B rings) in the same plane. The presence of the intramolecular H-bond was validated by a down-field signal (δ 10.17 ppm) for the NH proton in the 1H NMR spectrum of 1a. In contrast, the conformation of 1b shows a torsional angle of 54.14° [C1-N2-C3-C4] between the two aryl rings, caused by electronic repulsion between lone-pair electrons of the linker oxygen and the negatively charged ortho-nitro group. Therefore, we hypothesize that a non-planar molecular conformation might be favorable for enhancing antitumor potency. Even though 1a is less active than 1b, the NH linker of 1a is modifiable and steric hindrance can be introduced to promote a non-planar molecular conformation. Consequently, 6-chloro-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (3a), a tertiary amine derivative of 1a, was designed and synthesized. In another positive design direction, 3a contains a 4-methoxy-N-methylanilino moiety as also found in MPC-6827. Compound 3a exhibited significant cytotoxic activity against a panel of human tumor cell lines with low micromolar GI50 values of 1.55 to 2.20 μM. Accordingly, additional tertiary diarylamine derivatives 3–8 were designed, synthesized, and evaluated for antitumor activity. The new target compounds are shown in the general formula in Figure 2. The impact of substituents [R1 on the B-ring, R2 on the linker (Y), R3 and R4 on the A-ring] on the cytotoxic activity was investigated successively. Furthermore, new active leads with high potency were tested in anti-tubulin assays to identify a potential biological target and possible binding site. Our new results on the tertiary diarylamines, including chemical synthesis, cytotoxicity against human tumor cells, SAR results, and identification of biological target, are presented herein.

Figure 2.

A) Hits, design, and a general formula of new tertiary diarylamines. B) Preferred conformations of 1a and 1b. The torsional angle C1—N2—C3—C4 is defined as positive if, when viewed along the N2—C3 bond, atom C1 must be rotated clockwise to eclipse atom C4.

Chemistry

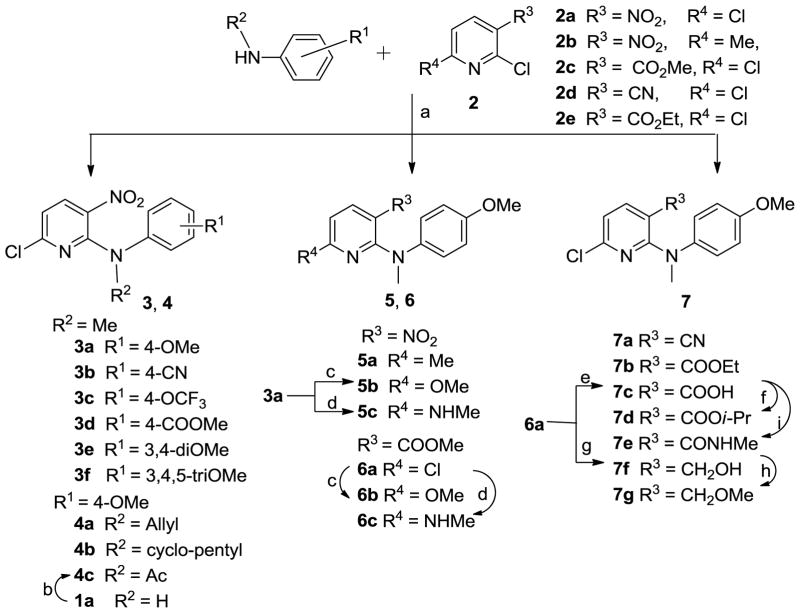

As shown in Scheme 1, the designed target compounds 3–7 could be synthesized from substituted 2-chloropyridines (2) and various commercially available anilines. Most of the compounds were prepared by a coupling reaction between 2 and a substituted aniline in t-BuOH in the presence of potassium carbonate either at room temperature for 12–24 h5 (method A for 3a, 3e, 3f) or under microwave irradiation at 120–160 °C for 10–30 min (method B for 3c, 3d).6,7 As an exception, the coupling of 2,6-dichloro-3-nitropyridine (2a) with N-methyl 4-cyanoaniline was carried out by direct heating under solvent-free conditions to provide 3b in 37% yield. Consistent with our previous results,8 the nucleophilic N-substituted aniline preferred to attack the 2,6-dichloropyridine (2)at the 2-chloro position, which is ortho to an electron-withdrawing substituent R3 (such as NO2, COOMe, and COOEt in 2a, 2c, and 2e, respectively) to produce corresponding series 3–7 compounds. However, when 3-cyano-2,6-dichloropyridine (2d) was treated with N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline, 2- (7a) and 6-anilino products were formed in a 1:2 ratio, indicating that the presence of the cyano (CN), a weak electron-withdrawing group, led to less selectivity between the two chlorinated ortho- and para-positions on the pyridine ring. By using the same aromatic nucleophilic substitution reaction, compounds 4a, 4b, 5a, 6a, 7a, and 7b were prepared from the appropriate chloropyridines 2a–e and N-substituted 4-methoxyanilines. Acetylation of hit 1a with acetic anhydride in the presence of a catalytic amount of concentrated sulfuric acid provided compound 4c. The 6-chloro in 3a and 6a was converted to a methoxy or methylamine group by treatment with sodium methoxide or methylamine in dry MeOH to produce corresponding compounds 5b, 6b or 5c, 6c, respectively. Hydrolysis of 6a under basic conditions gave the carboxylic acid compound 7c, which was esterified with 2-iodopropane in acetone to produce 7d. The treatment of 7c with 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) in the presence of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDCI) hydrochloride salt, followed by the reaction with methylamine (30% in MeOH) gave 7e, with 3-CONHMe (R3) on the pyridine ring, in moderate yield.9 Additionally, the ester group in 6a was reduced by reaction with lithium borohydride (LiBH4) to give 3-hydroxymethyl compound 7f, which was converted to 3-methoxymethyl compound 7g by treatment with iodomethane in the presence of sodium hydride in anhydrous DMF.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 3–7 series. a) neat, 140 °C, N2, 4 h for 3b; K2CO3/t-BuOH, r.t., 12–24 h or microwave irradiation. 120–160 °C, 10–30 min for others; b) Ac2O/H2SO4, 90 °C, 18 h; c) NaOMe/MeOH, reflux, 2 h; d) MeNH2/MeOH, reflux, 12 h; e) i. aq. NaOH (3N), THF/MeOH, rt, 36 h; ii. HCl (2N); f) i-PrI, K2CO3, acetone, reflux, 4 h; g) LiBH4, THF, MeOH, rt, 2 h; h) CH3I, NaH (60% oil suspension), THF, rt, 2 h; i) i. HOBt, EDCI, CH2Cl2, rt, 30 min; ii. NH2Me (30% in MeOH), 1.5 h, rt.

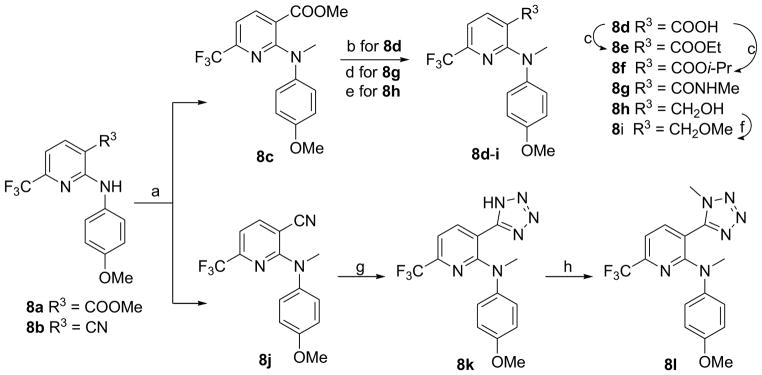

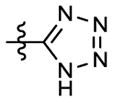

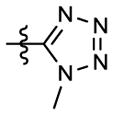

Scheme 2 shows the synthesis of 6-trifluoromethylpyridine compounds 8c–l from 3-substituted N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-amine 8a (R3 = COOMe) or 8b (R3 = CN), which were prepared by literature methods.10 Methylation of 8a and 8b with methyl iodide in the presence of sodium hydride in DMF at low temperature (0 °C) produced tertiary amines 8c and 8j, respectively. Hydrolysis, aminolysis, or reduction of the ester group in 8c produced corresponding benzoic acid (8d), N-methyl carboxamide (8g), and hydroxymethyl (8h) compounds, respectively. Further esterification of 8d with iodoethane or 2-iodopropane in refluxing acetone gave ethyl ester 8e and isopropyl ester 8f, respectively. Similarly to the preparation of 7g, methylation of 8h afforded methoxymethyl compound 8i. A tetrazolyl ring (R3) was formed11 from the cyano group in 8j by treatment with sodium azide and triethylamine hydrochloride in refluxing toluene to afford 8k. However, this reaction did not go to completion, and ca. one-third of the starting 8j was recovered, even after 36 h. Furthermore, methylation of 8k with dimethyl sulfate produced the corresponding 8l. All target compounds were identified by 1H NMR and MS spectroscopic data, and purity was determined by HPLC.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 8 series. a) CH3I, NaH (60% oil suspension), DMF, 0 °C, 1 h; b) i. aq. NaOH (3N), THF/MeOH, r.t, 36 h; ii. HCl (2N); c) EtI or i-PrI, K2CO3, acetone, reflux, 4 h; d) NH2Me, MeOH, rt, 4 days; e) LiBH4, THF, MeOH, rt, 2 h; f) CH3I, NaH (60% oil suspension), THF, rt, 2 h; g) NaN3, Et3N·HCl, toluene, reflux, 36 h; h) Me2SO4, K2CO3, acetone, reflux, 5 h.

Results and discussion

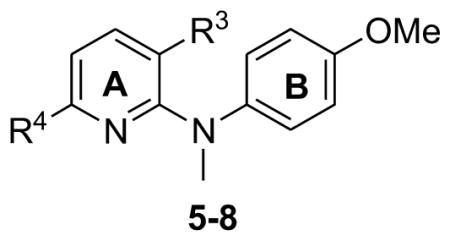

The 32 newly synthesized tertiary diarylamines (series 3–8) were first evaluated for cytotoxic activity using a HTCL panel, including A549 (lung carcinoma), DU145 (prostate cancer), KB (epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx), and KBVIN (vincristine-resistant KB), with paclitaxel as a reference compound. The in vitro anticancer activity (GI50) was determined using the established sulforhodamine B (SRB) method.12 The cytotoxicity data of all new tertiary amines in HTCL assays are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Some of the designed tertiary diarylamine compounds were more potent than hit 1a (GI50 values 2.40–13.5) in the HTCL assays. As shown in Table 1, compounds 3a with a para-methoxy (R1=OMe) and 3d with a para-ester (R1=COOMe) on the phenyl ring displayed low micromolar GI50 values ranging from 1.55 to 3.00 μM, and thus, were more potent than 3b with a para-cyano (21–27 μM) and 3e with 3,4-dimethoxy (15–18 μM) against the HTCL panel. However, corresponding compounds 3c and 3f with 4-trifluoromethoxy or 3,4,5-trimethoxy substitution, respectively, on the phenyl ring completely lost cytotoxic activity. These results indicated that a para-substituent on the phenyl ring could enhance the antiproliferative activity and a methoxy group was preferred to other substituents or multi-substituents on the phenyl ring. Consequently, in the series 4 compounds, the 4-methoxyphenyl moiety was retained, while the R2 group on the linker was varied. In comparison with 3a (R2 = Me, GI50 1.55–2.20 μM), compound 4a with a N-allyl group showed comparable potency, but a bulky N-cyclopentyl group or an electron-withdrawing N-acetyl group resulted in significantly reduced or no potency (see 4b and 4c). Thus, as we expected, a small alkyl group on the linker might favor enhanced cytotoxic activity.

Table 1.

Inhibitory activity of 3–4 against HTCL panel

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | GI50 ± SD (μM)a

|

||||

| A549 | KB | KBVIN | DU145 | |||

| 3a | 4-OMe | Me | 2.20 ± 0.20 | 1.78 ± 0.11 | 1.86 ± 0.30 | 1.55 ± 0.24 |

| 3b | 4-CN | Me | 24.0 ± 2.79 | 22.1 ± 2.52 | 27.0 ± 4.22 | 21.4 ± 3.89 |

| 3c | 4-OCF3 | Me | NAb | NA | NA | NA |

| 3d | 4-COOMe | Me | 3.00 ± 0.35 | 2.89 ± 0.24 | 2.87 ± 0.55 | 2.22 ± 0.22 |

| 3e | 3, 4-diOMe | Me | 18.4 ± 1.31 | 16.0 ± 0.62 | 16.5 ± 0.88 | 15.0 ± 0.95 |

| 3f | 3, 4, 5-triOMe | Me | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4a | 4-OMe | allyl | 3.33 ± 0.41 | 2.61 ± 0.16 | 3.15 ± 0.57 | 2.69 ± 0.35 |

| 4b | 4-OMe | c-pentyl | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4c | 4-OMe | Ac | 11.8 ± 2.36 | 14.3 ± 2.05 | 13.9 ± 1.25 | 11.2 ± 2.03 |

| 1a3 | 4-OMe | H | 13.5 | 7.19 | 2.40 | 3.83 |

|

| ||||||

| Paclitaxelc | 8.18 ± 1.01 nM | 7.77 ± 0.84 nM | 1803 ± 302 nM | 6.50 ± 0.43 nM | ||

Concentration of compound that inhibits 50% human tumor cell growth, presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), performed at least in triplicate.

Not active; test compound (20 μg/mL) did not reach 50% inhibition.

Positive control.

Table 2.

Inhibitory activity of 5–8 against HTCL panel

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R3 | R4 | GI50 ± SD (μM)b

|

||||

| A549 | KB | KBVIN | DU145 | |||

| 3a | NO2 | Cl | 2.20±0.20 | 1.78±0.11 | 1.86±0.30 | 1.55±0.24 |

| 5a | NO2 | Me | 4.42±0.44 | 2.92±0.25 | 4.19±0.97 | 3.35±0.55 |

| 5b | NO2 | OMe | 3.27±0.69 | 3.31±0.46 | 2.83±0.71 | 2.70±0.25 |

| 5c | NO2 | NHMe | 4.50±0.35 | 4.53±0.70 | 9.63±1.14 | 4.45±0.85 |

| 6a | COOMe | Cl | 0.23±0.01 | 0.26±0.04 | 0.20±0.03 | 0.21±0.04 |

| 6b | COOMe | OMe | 3.15±0.75 | 4.01±0.75 | 4.02±0.57 | 2.45±0.49 |

| 6c | COOMe | NHMe | 3.43±0.30 | 1.36±0.34 | 0.92±0.09 | 1.67±0.13 |

| 7a | CN | Cl | 20.4±2.51 | 22.1±1.94 | 18.1±3.73 | 20.4±4.59 |

| 7b | COOEt | Cl | 1.81±0.12 | 1.80±0.10 | 1.43±0.18 | 1.43±0.09 |

| 7c | COOH | Cl | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7d | COOPr-i | Cl | 22.0±1.64 | 14.5±0.40 | 17.3±1.58 | 17.8±0.34 |

| 7e | CONHMe | Cl | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 7f | CH2OH | Cl | 3.25±0.27 | 2.26±0.10 | 2.12±0.16 | 1.96±0.11 |

| 7g | CH2OMe | Cl | 0.30±0.03 | 0.33±0.07 | 0.20±0.01 | 0.25±0.01 |

| 8c | COOMe | CF3 | 0.35±0.05 | 0.41±0.09 | 0.19±0.01 | 0.25±0.04 |

| 8d | COOH | CF3 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8e | COOEt | CF3 | 1.46±0.13 | 1.52±0.10 | 1.30±0.15 | 1.30±0.13 |

| 8f | COOPr-i | CF3 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8g | CONHMe | CF3 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8h | CH2OH | CF3 | 2.13±0.09 | 1.92±0.28 | 1.75±0.11 | 1.71±0.08 |

| 8i | CH2OMe | CF3 | 1.20±0.02 | 1.64±0.04 | 1.43±0.20 | 1.29±0.11 |

| 8j | CN | CF3 | 7.21±1.20 | 15.3±2.33 | 7.91±1.56 | 10.7±2.49 |

| 8k |

|

CF3 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 8l |

|

CF3 | 1.82±0.50 | 1.47±0.34 | 1.26±0.09 | 1.16±0.05 |

|

| ||||||

| Paclitaxelc | 8.18±1.01 nM | 7.77±0.84 nM | 1803±302 nM | 6.50±0.43 nM | ||

Concentration of compound that inhibits 50% human tumor cell growth, presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), performed at least in triplicate.

Not active; test compound (20 μg/mL) did not reach 50% inhibition.

Positive control.

Next, we turned to modifications of the R3 and R4 substituents on the pyridine ring (A ring) (see Table 2). The R4 on the pyridine ring was changed to methyl, methoxy, or N-methylamine, rather than the chlorine atom in 3a. This change resulted in active compounds 5a–5c with GI50 values of 2.70–9.63 μM. Then, because a nitro group is generally considered to be a moiety associated with risk and, thus, unacceptable in pharmaceutical agents,13 compounds 6a–6c with a methoxy carbonyl (R3) rather than the nitro group in the series 5 compounds and various R4 groups (Cl, OMe, and NHMe, respectively) on the A-ring were synthesized and evaluated against the HTCL panel. Compound 6a exhibited sub-micromolar GI50 values (0.20–0.26 μM) and was ten-fold more potent than 3a and 5a–c (GI50 1.55–9.63 μM), 6b displayed similar potency to 5b, while 6c showed ten-fold higher potency against KBVIN cell growth (GI50 0.92 μM) compared with 5c (GI50 9.63 μM). The results from series 6 indicated that the R3 on the pyridine ring can be modified to enhance potency and might have a greater impact on the potency than R4. Furthermore, two additional compound series, 7 (a–g) and 8 (c–l) with a chloro or trifluoromethyl R4 group, respectively, were synthesized in parallel to investigate the impact of various R3 groups on the antiproliferative activity. Among them, 3-methyl or -ethyl ester pyridine compounds 7b, 8c, and 8e (R3 = COOMe or COOEt) showed high potency with low to sub-micromolar GI50 values (0.19–1.81 μM) similar to series 6, regardless of whether R4 was chloro or trifluoromethyl. In contrast, the presence of a 3-cyano (7a and 8j), 3-isopropyl ester (7d and 8f), 3-carboxylic acid (7c and 8d), or 3-methylamide (8g and 7e) on the pyridine ring resulted in substantially reduced (GI50 >7.21μM) or no cytotoxic activity. Therefore, while a methyl or ethyl ester R3 group was beneficial, a bulky (isopropyl ester) or negatively charged (such as carboxylic acid at physiological pH) R3 substituent impaired the cytotoxic activity. Interestingly, we observed that 3-methoxymethylpyridines 7g and 8i (R3 = CH2OMe) and 3-hydroxymethylpyridines 7f and 8h (R3 = CH2OH) also were potent with GI50 values of 0.20–3.25 μM, generally comparable with 3-methyl and -ethyl ester compounds. Notably, compounds 6a (R3=COOMe, R4=Cl), 7g (R3= CH2OMe, R4=Cl), and 8c (R3=COOMe, R4=CF3) exhibited GI50 values between 0.19 and 0.41 μM against all four HTCL. Similarly to 7c and 8d, compound 8k with a 3-tetrazole ring, a bio-isostere of a carboxylic acid, on the pyridine ring was inactive. However, with a methylated tetrazole that cannot ionize, compound 8l exhibited high potency with low micromolar GI50 values ranging from 1.16 to 1.82 μM against the HTCL panel.

More interestingly, we found that most active compounds in the series of tertiary diarylamine showed equal or slightly better potency against both the KB and paclitaxel-resistant KBVIN cell lines (see Tables 1 and 2). In contrast, paclitaxel showed nanomolar activity against KB cells (GI50 8 nM), but significantly lower potency (GI50 1800 nM) against the KBVIN cell line, which over-expresses P-glycoprotein, a drug efflux transporter. These results indicated that these types of active compounds are not substrates of P-glycoprotein and can overcome paclitaxel-resistance, providing a therapeutic advantage over paclitaxel.

In investigating possible biological target(s), the three most active compounds 6a, 7g, and 8c (GI50 0.19–0.41 μM) were tested in tubulin assays. As shown in Table 3, they showed high activity for inhibition of tubulin assembly, with IC50 values ranging from 1.4 to 1.7 μM, which are comparable to those with CA-4 (IC50 1.2 μM), a tubulin inhibitor currently in phase II clinical trials, in the same assay. Furthermore, they inhibited the binding of colchicine to tubulin (≥80%). These results suggest that these active diarylamines might exert their effects by inhibiting tubulin polymerization targeted at the colchicine binding site.

Table 3.

| compound | inhibition of tubulin assembly IC50 (μM) ± SD | inhibition of colchicine binding (%) ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| 6a | 1.40 ± 0.01 | 80 ± 2.0 |

| 7g | 1.50 ± 0.20 | 88 ± 0.5 |

| 8c | 1.70 ± 0.20 | 82 ± 1.0 |

|

| ||

| CA-4c | 1.20 ± 0.20 | 98 ± 0.6 |

The tubulin assembly assay measured the extent of assembly of 10 μM tubulin after 20 min at 30 °C.

Tubulin: 1 μM. [3H]colchicine: 5 μM. Inhibitor: 5 μM. Incubation was performed for 10 min at 37 °C.

reference compound is a drug candidate in phase II clinical trial.

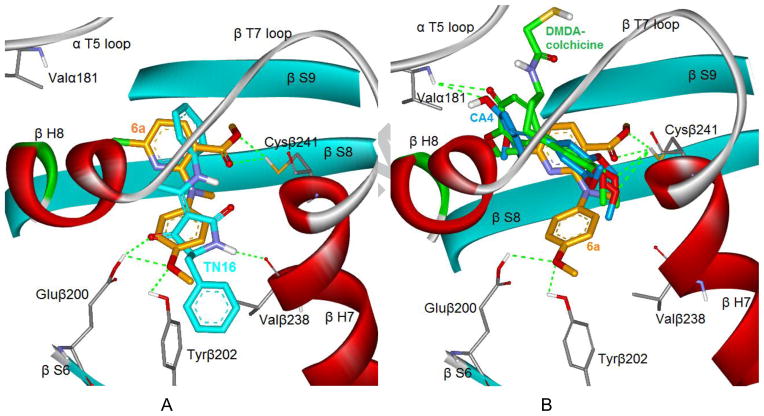

To better understand how the diarylamine analogues interact with tubulin, we investigated the binding mode of 6a at the colchicine binding domain in the tubulin dimer by using CDOCKER in the Discovery Studio 3.0 software. We attempted to dock 6a into two different crystal structures, the tubulin/TN16 complex (PDB ID code: 3HKD) and the tubulin/DMDA-colchicine complex (PDB ID code: 1SA0). We selected the former crystal structure as our modeling system, because 6a showed a lower binding energy (−14.50 kcal/mol) in 3HKD than in 1SA0 (−9.74 kcal/mol) and superposed very well with the native ligand TN16 in the 3HKD structure. Figure 3A illustrates the binding mode of 6a (orange) with tubulin protein and its overlap with TN16 (cyan). The methoxy group on the B-ring of 6a formed two hydrogen bonds with the carboxyl group of Glu200 and the hydroxyl of Tyr202 in β-S6, while TN-16 formed one H-bond also with Glu200 and another H-bond with Val238 in β-H7. The pyridine moiety (A-ring) of 6a bound in the lipophilic pocket formed by the side chains of amino acids in β-S8 and β-H7, and the ester group on the A-ring showed two hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Cys241, a key amino acid in the colchicine binding site. For comparison, we superposed 6a, DMDA-colchicine (the native ligand of 1SA0), and CA-4 into the same docking model, as shown in Figure 3B. While the TN16 binding site extended deeply into the β-subunit side and less into the α-subunit,14,15 DMDA-colchicine (green) and CA-4 (blue) bound at the interface between the α- and β-subunits of the tubulin dimer, and showed an overlap only with the pyridine ring of 6a. The 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl moieties found in both DMDA-colchicine and CA-4 overlapped well and also formed H-bonds with the thiol group of Cys241, which plays a locating role for most tubulin inhibitors binding at the colchicine binding site. The theoretical model of 6a supports our bioassay results and can explain, at least partially, the high potency of 6a and the preference for the ester group on the pyridine ring. Meanwhile, it also reveals obvious differences in the binding conformations and orientations between our active compounds and CA-4 in the colchicine binding site.

Figure 3.

A) A predicted mode of compound 6a (orange stick model) binding with tubulin (PDB ID code: 3HKD), and overlapping with TN16 (cyan stick model, the native ligand of 3HKD); B) The superimposition of docked compound 6a with DMDA-colchicine (green stick model, the native ligand of 1SA0) and CA-4 (blue stick model). Surrounding amino acid side chains are shown in gray stick format and labeled. The hydrogen bonds are shown by green dashed lines and the distance between the ligands and protein is less than 3 Å

In summary, three new leads 6a, 7g, and 8c exhibited promising cytotoxic activity in human tumor cell line assays with submicromolar GI50 values, significant potency against tubulin assembly, and inhibitory activity for colchicine binding to tubulin protein. Notably, the active tertiary diarylamine compounds showed high potency against paclitaxel-resistant KBVIN cell lines, providing a potential advantage over paclitaxel. In addition, molecular modeling studies revealed that the active 6a and CA-4 might have different binding modes. Therefore, our active tertiary diarylamines might be a novel class of tubulin inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site. Current SAR studies on several series of N-methyl-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)pyridin-2-amines revealed the following conclusions: 1) a tertiary amine linker is crucial for enhanced antitumor activity, and a methyl group is better than others, 2) a para-methoxyphenyl moiety is favorable for antitumor activity, 3) the R3 group on the pyridine ring can be modified to improve potency, and methyl ester and methoxymethyl groups are better than other groups tested, 4) the R4 substituent on the pyridine ring also contributes to the cytotoxic activity, but seems to have less impact than R3. We will use these initial promising results to guide our further optimization of new compounds as tubulin inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site. In addition, because various tubulin inhibitors targeting the colchicine binding site have been reported to selectively disrupt the cytoskeleton of proliferating endothelial cells as vascular disrupting agents (VDAs),16, 17 further studies on our newly discovered active compounds will be necessary to develop a new class of antitumor drug with a new mechanism of action as a new approach for treating cancers and tumors.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

The nuclear magnetic resonance (1H and 13C NMR) spectra were measured on a JNM-ECA-400 (400 MHz and 100 MHz, respectively) spectrometer using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal standard. The solvent used was CDCl3 unless otherwise indicated. Mass spectra (MS) were measured on API-150 mass spectrometer with the electrospray ionization source from ABI, Inc. Melting points were measured with a RY-1 melting apparatus without correction. The microwave reactions were performed on a microwave reactor from Biotage, Inc. Medium- pressure column chromatography was performed using a CombiFlash® Companion system from ISCO, Inc. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel GF254 plates. Silica gel GF254 and H (200–300 mesh) from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Company were used for TLC, preparative TLC (PTLC), and column chromatography, respectively. All commercial chemical reagents were purchased from Beijing Chemical Works or Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. Purities of target compounds were determined by using an Agilent HPLC-1200 with UV detector and an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm) eluting with a mixture of solvents A and B (acetonitrile/water 80:20), flow rate 0.8 mL/min and UV detection at 254 nm.

6-Chloro-N-(4-cyanophenyl)-N-methyl-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (3b)

A mixture of 2,6-dichloro-3-nitropyridine (2a, 94 mg, 0.5 mmol) and N-methyl 4-cyanoaniline (80 mg, 0.6 mmol) was heated neat at 120 °C under N2 protection for 4 h with stirring. Then the mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 and purified by preparative TLC (CH2Cl2/petroleum ether/MeOH = 1/1.5/0.04) to obtain 40 mg of 3b in 37% yield, together with recovery of 24 mg of 2a, yellow solid, mp 98–100 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.66 (3H, s, NCH3), 7.02 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 7.09 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.58 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.07 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 289 (M+1, 100), 291 (M+3, 35); HPLC purity 97.7%.

General procedure for coupling of substituted 2-chloropyridine and N-alkylaniline. Method A (traditional)

A mixture of a substituted 2-chloropyridine (2, 1.0 mmol), N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline (1.5 mmol), and anhydrous potassium carbonate (2 mmol) in t-BuOH was stirred at rt for 12–24 h monitored by TLC until the reaction was complete. The mixture was poured into ice-water, the pH adjusted to ca. 3.0 with aq HCl (2N), and the resulting solution extracted with CH2Cl2 three times. The combined organic phases were washed with water and brine, successively, until neutral and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 overnight. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient elution: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–50%) to obtain corresponding pure product. Method B (microwave irradiation): A mixture of 2 (1.0 mmol), substituted aniline (1.5 mmol), and anhydrous potassium carbonate (414 mg, 3.0 mmol) in 3 mL of t-BuOH was heated at 120–160 °C with microwave-assistance for 10–30 min with stirring. The reaction mixture was then poured into ice-water, pH adjusted to ~3.0 with aq HCl (2N), and solid crude product was filtered. The product was then purified by the same methods as in Method A above.

6-Chloro-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-3-nitropyridine-2-amine (3a)

Method A. Starting with 193 mg of 2a and 206 mg of N-methyl 4-methoxyanaline to produce 240 mg of 3a, 82% yield, orange solid recrystallized from MeOH, mp 96–97 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.54 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.76 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.00 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.88 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 294 (M+1, 100), 296 (M+3, 32); HPLC purity 99.5%.

6-Chloro-N-methyl-3-nitro-N-(4-trifluoromethoxyphenyl)pyridin-2-amine (3c)

Method B. Starting with 193 mg of 2a and 288 mg of N-methyl-4-trifluoro methoxyaniline at 120 °C for 30 min to produce 198 mg of 3c, 57% yield, yellow liquid. 1H NMR δ ppm 3.59 (1H, s, NCH3), 6.87 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 7.08 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.16 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.96 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 348 (M+1, 100), 350 (M+3, 25); HPLC purity 97.2%.

6-Chloro-N-methyl-N-(4-methoxycarbonylphenyl)-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (3d)

Method B. Starting with 193 mg of 2a and 248 mg of methyl N-methyl-4-amino benzoate at 160 °C for 15 min to produce130 mg of 3d, 41% yield, brown solid, mp 106–107 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.67 (1H, s, NCH3), 3.89 (1H, s, OCH3), 6.94 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 7.07 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.98 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.02 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 322 (M+1, 100), 324 (M+3, 28); HPLC purity 97.2%.

6-Chloro-N-(3,4-dimethoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (3e)

Method A. Starting with 193 mg of 2a and 250 mg of N-methyl-3,4-dimethoxyaniline to produce 262 mg of 3e, 81% yield, red solid, mp 145–146 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.56 (s, 3H, NCH3), 3.83 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.85 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.60 (2H, m, ArH-2′ and 6′), 6.78 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 6.80 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-4′), 7.88 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%), 324.3 (M+1, 18), 325.9 (M+3, 6), 290.1 (M-33, 100); HPLC purity 99.2%.

6-Chloro-N-methyl-3-nitro-N-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)pyridin-2-amine (3f)

Method A. Starting with 193 mg of 2a and 250 mg of N-methyl-3,4,5-trimethoxyaniline to produce 268 mg of 3f, 76% yield, orange solid, mp 138–140 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.60 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.80 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.83 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.26 (2H, s, ArH-2′,6′), 6.82 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 7.91 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 324.3 (M+1, 18), 325.9 (M+3, 6), 290.1 (M-33, 100); HPLC purity 99.5%.

N-Allyl-6-chloro-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (4a)

Method B. Starting with 193 mg of 2a and 244 mg of N-allyl-4-methoxyaniline at 120 °C for 10 min to produce 168 mg of 4a, 53% yield, red liquid. 1H NMR δ ppm 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.63 (2H, d, J = 5.6 Hz, NCH2), 5.16 and 5.18 (each 1H, dd, J = 17.6 Hz and 1.2Hz, CH2=), 5.99 (1H, m, CH), 6.76 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 6.81 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.98 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.87 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 320 (M+1, 100), 322 (M+3, 25); HPLC purity 99.4%.

6-Chloro-N-cyclopentyl-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (4b)

Method B. Starting with 194 mg of 2a and 288 mg of N-cyclopentyl-N-4-methoxyaniline at 160 °C for 20 min to produce 196 mg of 4b, 50% yield, yellow solid, mp 93–94 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.49-1.61 (6H, m, CH2 × 3), 2.02 (2H, m, CH2), 3.79 (1H, s, OCH3), 4.93 (1H, m, CH), 6.70 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.93 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.69 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 348 (M+1, 100), 350 (M+3, 32); HPLC purity 98.7%.

N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-6-methyl-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (5a)

Method B. Starting with 174 mg of 2b and 206 mg of N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline at 140 °C for 20 min to produce 154 mg of 5a, 56% yield, yellow solid, mp 97–98 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 2.53 (3H, s, CH3), 3.53 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.64 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 6.82 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.99 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.86 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 274 (M+1, 100); HPLC purity 98.5%.

Methyl 6-chloro-2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminonicotinate (6a)

Method B. Starting with 206 mg of methyl 2,6-dichloronicotinate (2c) and 206 mg of N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline at 160 °C for 30 min to produce 186 mg of 6a, 60% yield, pale yellow solid, mp 79–81 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.28 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.47 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.74 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 6.84 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.02 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); 13C NMR δ ppm 41.23, 51.79, 55.57, 113.21, 114.07, 114.74, 115.45, 125.55, 128.34, 141.30, 141.72, 151.33, 156.81, 156.98, 167.35; MS m/z (%) 307 (M+1, 100), 309 (M+3, 29); HPLC purity 99.2%.

6-Chloro-3-cyano-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methylpyridin-2-amine (7a)

Method B. Starting with 173 mg of 3-cyano-2,6-dichloropyridine (2e) and 205 mg of N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline at 160 °C for 15 min to produce 32 mg of 7a, 12% yield, white solid, mp 137–138 °C; 1HNMR δ ppm 3.47 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.85 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.18 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 6.99 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.14 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.38 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4). MS m/z (%): 274 (M+1, 100), 276 (M+3, 31); HPLC purity 99.0%.

Ethyl 6-chloro-2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminonicotinate (7b)

Method B. Starting with 220 mg of ethyl 2,6-dichloronicotinate (2d) and 205 mg of N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline at 160 °C for 30 min to produce 173 mg of 7b, 54% yield, yellow solid, mp 79–81 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.08 (3H, t, J = 7.6 Hz, CH3), 3.47 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.70 (2H, q, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.73 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.03 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 321.3 (M+1, 58), 323.3 (M+3, 20), 275.1 (M-45, 100); HPLC purity 96.7%.

6-Chloro-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methylcarbonyl-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (4c)

To a solution of 2a (280 mg, 1.0 mmol) in Ac2O (8 mL) was added a drop of concentrated H2SO4. The mixture was heated at 100 °C under N2 protection for 18 h with stirring. After the reaction was completed, the mixture was poured into ice-water and neutralized with 5% aq. NaOH. The collected solid was further purified by flash chromatography [gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–50%] to obtain 249 mg of pure 4c, 77% yield, yellow solid, mp 146–147 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 2.01 (3H, s, CH3), 3.86 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.99 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.31 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 7.49 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 8.22 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 322 (M+1, 100), 324 (M+3, 28); HPLC purity 97.8%.

6-Methoxy-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-3-nitropyridin-2-amine (5b)

A mixture of 3a (117 mg, 0.4 mmol) and NaOMe (ca. 1.0 mmol) in 3 mL of MeOH was refluxed for 2 h with stirring. After the reaction was finished, the mixture was poured into ice-water to obtain 108 mg of pure 5b as a yellow solid, 93% yield, mp 56–57 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.54 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.99 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.19 ( 1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, PyH-5), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.02 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.03 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 290 (M+1, 100); HPLC purity 95.6%.

Methyl 6-methoxy-2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminonicotinate (6b)

Prepared in the same manner as for 5b. Starting with 123 mg of 6a to obtain119 mg of 6b in 98% yield, white solid, mp 78–80 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.28 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.48 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.96 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.18 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-5), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.03 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.71 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, PyH-4). MS m/z (%)303 (M+1, 24), 271 (M-31, 100); HPLC purity 97.9%.

N2,N6-Dimethyl-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-3-nitropyridin-2,6-diamine (5c)

Compound 3a (117 mg, 0.2 mmol) in 3 mL of 30% methylamine-MeOH solution was refluxed for 12 h with stirring. After the reaction was completed, the mixture was poured into ice-water, and the resulting red solid was collected to give 86 mg of pure 5c, 75% yield, mp 169–170 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.03 (3H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, NCH3), 3.49 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 5.01 (1H, bs, NH), 5.87 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, PyH-5), 6.81 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.02 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 8.00 (1H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 289 (M+1,27), 255 (M-33, 100); HPLC purity 100.0%.

Methyl 2-[N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)]amino-6-methylaminonicotinate (6c)

Prepared in the same manner as for 5c. Starting with 123 mg of 6a to obtain 96 mg of 6c, 80% yield, white solid, mp 88–90 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 2.97 (3H, d, J = 5.2 Hz, NHCH3), 3.28 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.43 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.69 (1H, bs, NH), 5.88 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, PyH-5), 6.80 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.01 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.67 (1H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 302 (M+1, 1), 227 (M-7, 100); HPLC purity 100.0 %.

6-Chloro-2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminonicotinic acid (7c)

To a solution of 6a (154 mg, 0.5 mmol) in THF/MeOH (1.5 mL/1.5 mL) was added 3N aq NaOH (3.0 mL) dropwise with stirring at rt for 36 h. The mixture was poured into 20 mL of water. After removal of insoluble substance, the water phase was acidified with aq. HCl (2N) to pH 2. The precipitated solid was collected, washed with water, and dried to give 112 mg of pure 7c, 77% yield, yellow solid, mp 138–140 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.43 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.72 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.81 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.90 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 7.00 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.90 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4). MS m/z (%) 293.2 (M+1, 100), 295.3 (M+3, 45); HPLC purity 95.2%.

Isopropyl 6-chloro-2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminonicotinate (7d)

A mixture of 7c (59 mg, 0.2 mmol), i-PrI (68 mg, 0.4 mmol), and K2CO3 (55 mg, 0.4 mmol) in 5 mL of acetone was refluxed for 4 h. K2CO3 was filtered out, and acetone was removed under reduced pressure. The solid residue was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–40%) to give 55 mg of pure 7d, 82% yield, pale yellow solid, mp 56–58 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.02 (6H, d, J = 6.0 Hz, CH3×2), 3.46 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.76 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.60 (1H, m, CH), 6.73 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 6.82 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.02 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.59 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 335.4 (M+1, 32), 337.3 (M+3, 11), 275.1 (M-59+, 100); HPLC purity 95.5%.

N-Methyl 6-chloro-2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminonicotinamide (7e)

A mixture of 7c (84 mg, 0.29 mmol), EDCI (86 mg, 0.45 mmol) and HOBt (61 mg, 0.45 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (4 mL) was stirred at rt for 30 min, and then 30% methyl amine (0.18 mL)-MeOH solution was added dropwise at 0 °C with stirring over 15 min, followed by warming to to rt for an additional 90 min. After adding water (20 mL), the product was extracted with CH2Cl2 three times. The combined organic phase was washed with water and brine, successively, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 overnight. After removal of solvent in vacuo, crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–50%) to give 59 mg of pure 7e, 66% yield, white solid, mp 150–152 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 2.52 (3H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, NHCH3), 3.39 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.16 (1H, br, NH), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.90 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 6.95 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.74 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 306 (M+1, 16), 308 (M+3, 6), 275.1 (M-30, 100); HPLC purity 98.3%.

6-Chloro-3-hydroxymethyl-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methylpyridin-2-amine (7f)

To a solution of 6a (123 mg, 0.4 mmol) in 5 mL of anhydrous THF, Light (88 mg, 4.0 mmol) was added at 0 °C with stirring over 15 min, and then the solution was warmed to rt for 30 min. MeOH (0.5 mL) was then added dropwise to the mixture with stirring for an additional 30 min. The mixture was poured into ice-water and extracted with EtOAc three times. Combined organic phase was washed successively with water and brine, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 overnight. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–50%) to to produce 91 mg of pure 7f, 82% yield, yellow oil. 1H NMR δ ppm 3.35 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.98 (2H, s, CH2), 6.84 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.92 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4), 6.95 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.60 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5); MS m/z (%) 279.2 (M+1, 100), 281.2 (M+3, 34); HPLC purity 99.4%.

6-Chloro-3-methoxymethyl-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methylpyridin-2-amine (7g)

To a solution of 7f (51 mg, 0.18 mmol) and MeI (0.03 mL, 0.54 mmol) in 6 mL of anhydrous THF was added NaH (22 mg, 0.54 mmol, 60% oil suspension) at 0 °C and stirred for 30 min at 0 °C and for 2 h at rt. The mixture was poured into ice-water and extracted with EtOAc three times. The combined organic phase was washed with water and brine, successively, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 overnight. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the crude product was purified by flash column chromatography (gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–30%) to give 41 mg of pure 7g, 78% yield, yellow oil. 1H NMR δ ppm 3.15 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.36 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.69 (2H, s, OCH2), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.82 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.91 (3H, m, PyH-5 and ArH-3′,5′), 7.58 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); 13C NMR δ ppm 42.07, 55.45, 58.29, 70.16, 114.59, 115.12, 116.09, 122.63, 125.09, 128.22, 138.86, 142.20, 147.50, 156.27, 157.05; MS m/z (%) 261 (M-31+, 100), 293 (M+1, 52), 295.3 (M+3, 18); HPLC purity 99.3%.

Methyl 2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-6-trifluoromethylnicotinate (8c)

To a solution of methyl 6-chloro-2-[N-(4-methoxyphenyl)amino]-6-trifluoro- methylnicotinate (8a, 120 mg, 0.37 mmol), and MeI (0.07 mL, 1.13 mmol) in DMF (3–5 mL) was added NaH (44 mg, 1.1 mmol, 60% oil suspension) at 0 °C with stirring for 1 h. After the reaction was completed, the mixture was poured into ice-water and extracted with EtOAc three times. The combined organic phase was washed with water and brine successively, and dried over anhydrous Na2SO4 overnight. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the crude product was purified by flash chromatography [gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–50%] to produce 116 mg of 8c, 92% yield, yellow solid, mp 99–101 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.30 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.50 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.85 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-5), 7.74 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, PyH-4); 13C NMR δ ppm 40.94, 51.83, 55.47, 109.46, 114.66 (2C), 118.36, 125.78 (2C), 140.10, 140.92, 147.63, 147.97, 156.32, 157.05, 167.19; MS m/z (%) 341 (M+1, 6), 309 (M-31, 100); HPLC purity 97.2%.

2-(N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-6-trifluoromethylnicotinic acid (8d)

Prepared in a similar manner as for 7c. Starting with 170 mg of 8c to produce 118 mg of 8d, 72% yield, mp 146–148 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.48 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.71 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.80 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.02 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.16 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.95 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 261 (M−65−, 100), 325 (M−1−, 46); HPLC purity 97.4%.

Ethyl 2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-6-trifluoromethylnicotinate (8e)

Prepared in a similar manner as for 7d. Starting with 8d (163 mg, 0.5 mmol), EtI (153 mg, 1.0 mmol), and K2CO3 (138 mg, 1.0 mmol) to produce 156 mg of 8e, 88% yield, yellow solid, mp 105–106 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.09 (3H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, CH3), 3.50 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.70 (3H, q, J = 7.2 Hz, OCH2), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.01 (2H, d, J = 5.6 Hz, CH2), 6.84 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.74 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4). MS m/z (%)355.2 (M+1, 28), 309.3 (M-45, 100); HPLC purity 100.0%.

Isopropyl 2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-6-trifluoromethylnicotinate (8f)

Prepared in a similar manner as for 7d. Starting with 8d (42 mg, 0.13 mmol), i-PrI (66 mg, 0.39 mmol), and K2CO3 (54 mg, 0.39 mmol) to produce 45 mg of 8f, 94% yield, pale yellow solid, mp 108–109 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.04 (6H, d, J = 6.4 Hz, CH3×2), 3.49 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.77 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.59 (1H, m, CH), 6.84 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 7.04 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.06 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.72 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4). MS m/z (%) 369.3 (M+1, 8), 309.3 (M-59, 100); HPLC purity 96.5%.

N-Methyl 2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-6-trifluoromethyl nicotinamide (8g)

A solution of 8c (49 mg, 0.14 mmol) in 3 mL of 30% methylamine-MeOH solution was stirred at rt for 4 days. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the crude product was purified with flash column chromatography (gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–60%) to provide 35 mg of 8g, 74% yield, white solid, mp 151–152 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 2.51 (3H, d, J = 4.8 Hz, NHCH3), 3.42 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.00 (1H, br, CONH), 6.84 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.98 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.20 (1H, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.84 (1H, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 340 (M+1, 4), 309 (M−30, 100); HPLC purity 100.0%.

3-Hydroxymethyl-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-6-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-ami ne (8h)

Prepared in a similar manner as for 7f. Starting with 8c (136 mg, 0.4 mmol) to produce 102 mg of 8h, 82% yield, yellow oil. 1H NMR δ ppm 3.38 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.80 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.01 (2H, d, J = 5.6 Hz, CH2), 6.84 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.96 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.26 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.80 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 312 (M+1, 100); HPLC purity 99.1%.

3-Methoxymethyl-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-6-trifluoromethylpyridine-2-a mine (8i)

Prepared in a similar manner as for 7g. Starting with 8h (110 mg, 0.35 mmol), MeI (0.06 mL, 1.0 mmol), and NaH (40 mg, 1.0 mmol, 60% oil suspension) to produce 94 mg of 8i, 82% yield, yellow oil. 1H NMR δ ppm 3.17 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.39 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.72 (2H, s, OCH2), 3.80 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.94 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.23 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.76 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4). MS m/z (%) 327 (M+1, 27), 295 (M-31, 100); HPLC purity 99.6%.

3-Cyano-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-6-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-amine (8j)

The preparation, work-up, and purity are the same as for 8c. Starting with 3-cyano-N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-6-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-amine (8b) (586 mg, 2.0 mmol), MeI (0.25 mL, 4.0 mmol), and NaH (160 mg, 60% oil suspension) in 3 ml of DMF at 0 °C with stirring for 1 hour to afford 565 mg of pure 8j, 92% yield, white solid, mp 83–84 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.47 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.84 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.96 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.98 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.20 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.77 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 308 (M+1, 100); HPLC purity 97.6%.

N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-3-(1H-tetrazol-5-yl)-6-trifluoromethylpyridin-2-amine (8k)

To a solution of 8j (417 mg, 1.3 mmol) in toluene (5 mL) was added 4 drops of water, NaN3 (266 mg, 4.1 mmol), and Et3N·HCl (562 mg, 4.1 mmol) successively. The mixture was heated at reflux temperature for 36 h, After cooling to rt, the mixture was added to saturated aq. Na2CO3 (5 mL) and water (5 mL), and then extracted with petroleum ether three times. The organic phase was washed successively with water and brine, and dried over MgSO4. After removal of petroleum ether in vacuo, 176 mg of unreacted 8c was recovered from the organic phase. The water phase was acidified with aq. HCl (2N) to pH 2~3, filtered, and dried to give 262 mg of 8k, 95% yield, yellow solid, mp 225 °C (decomposition); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ ppm 3.36 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.62 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.63 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.82 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.47 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.96 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4). MS m/z (%) 349 (M-1, 60), 278 (M-72, 100); HPLC purity 95.5%.

N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl-3-(1-methyl-tetrazol-5-yl)-6-trifluoromethylpyrid in-2-amine (8l)

A mixture of 8k (101 mg, 0.29 mmol), Me2SO4 (0.05 mL, 0.58 mmol), and K2CO3 (80 mg, 0.58 mmol) in acetone (5 mL) was refluxed for 5 h. After cooling to rt, additional acetone (ca. 10 mL) was added and solid K2CO3 was filtered out. After removal of solvent in vacuo, the residue was purified with flash column chromatography (gradient eluant: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–30%) to afford 55 mg of 8l, 52% yield, pale yellow solid, mp 115–116 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.51 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.69 (3H, s, NCH3), 4.08 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.60 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-2′,6′), 6.83 (2H, d, J = 9.2 Hz, ArH-3′,5′), 7.21 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-5), 7.83 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz, PyH-4); MS m/z (%) 365 (M+1, 3), 279 (M-85, 100); HPLC purity 100.0%.

Antiproliferative Activity Assay

Target compounds were assayed by SRB method for cytotoxic activity using the HTCL assay according to procedures described previously.18,19,20 The panel of cell lines included human lung carcinoma (A-549), epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx (KB), P-gp-expressing epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx (KBVIN), and prostate cancer (DU145). The cytotoxic effects of each compound were expressed as GI50 values, which represent the molar drug concentrations required to cause 50% tumor cell growth inhibition.

Tubulin Assays

Tubulin assembly was measured by turbidimetry at 350 nm as described previously.21 Assay mixtures contained 1.0 mg/mL (10 μM) tubulin and varying compound concentrations were pre-incubated for 15 min at 30 °C without guanosine 5′-triphosphate (GTP). The samples were placed on ice, and 0.4 mM GTP was added. Reaction mixtures were transferred to 0 °C cuvettes, and turbidity development was followed for 20 min at 30 °C following a rapid temperature jump. Compound concentrations that inhibited increase in turbidity by 50% relative to a control sample were determined.

Inhibition of the binding of [3H]colchicine to tubulin was measured as described previously.22 Incubation of 1.0 μM tubulin with 5.0 μM [3H]colchicine and 5.0 μM inhibitor was for 10 min at 37 °C, when about 40–60% of maximum colchicine binding occurs in control samples.

Molecular Modeling Studies

All molecular modeling studies were performed with Discovery Studio 3.0 (Accelrys, San Diego, USA). The crystal structures of tubulin in complex with TN16 (PDB: 3HKD) and with DMDA-colchicine (PDB: 1SA0) were downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) for possible use in the modeling study. We selected the structure 3HKD as our modeling system, because of lower binding energy of 6a with it and matched binding orientation between 6a and TN16. The CDOCKER was used to evaluate and predict in silico binding free energy of the inhibitors and automated docking. The protein protocol was prepared by several operations, including standardization of atom names, insertion of missing atoms in residues and removal of alternate conformations, insertion of missing loop regions based on SEQRES data, optimization of short and medium size loop regions with Looper Algorithm, minimization of remaining loop regions, calculation of pK, and protonation of the structure. The receptor model was typed with the CHARMm forcefield. A binding sphere with radius of 9Å was defined through the native ligand as the binding site for the study. The docking protocol employed total ligand flexibility and the final ligand conformations were determined by the simulated annealing molecular dynamics search method set to a variable number of trial runs. The docked ligands (6a, TN16, DMDA-colchicine, and CA-4) were further refined using in situ ligand minimization with the Smart Minimizer algorithm by the standard parameters. The ligand and its surrounding residues within the above defined sphere were allowed to move freely during the minimization, while the outer atoms were frozen. The implicit solvent model of Generalized Born with Molecular Volume (GBMV) was also used to calculate the binding energies.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was supported by Grants 81120108022 and 30930106 from the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) awarded to Lan Xie and NIH Grant CA17625-32 from the National Cancer Institute awarded to K. H. Lee. This study was also supported in part by the Taiwan Department of Health, China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence (DOH100-TD-C-111-005).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Stanton RA, Gernert KM, Nettles JH, Aneja R. Med Res Rev. 2011;31:443. doi: 10.1002/med.20242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:790. doi: 10.1038/nrd3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XF, Tian XT, Ohkoshi E, Qin BJ, Liu YN, Wu PC, Hour MJ, Hung HY, Huang R, Bastow KF, Janzen WP, Jin J, Morris-Natschke S, Lee KH, Xie L. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:6224. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Using the ChemBioDraw Ultra 12.0 software

- 5.Schmid S, Röttgen M, Thewalt U, Austel V. Org Biomol Chem. 2005;3:3408. doi: 10.1039/b508819b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frlan R, Kikelj D. Synth. 2006;14:2271. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li F, Wang QR, Ding ZB, Tao FG. Org Lett. 2003;5:2169. doi: 10.1021/ol0346436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qin BJ, Jiang XK, Lu H, Tian XT, Barbault F, Huang L, Qian K, Chen CH, Huang R, Jiang S, Lee KH, Xie L. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4906. doi: 10.1021/jm1002952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onnis V, Cocco MT, Lilliu V, Congiu C. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:2367. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.11.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cocco MT, Congiu C, Onnis V, Morelli M, Felipo V, Cauli O. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:4169. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He XY, Zou P, Qiu J, Hou L, Jiang S, Liu S, Xie L. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:6726. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinstein LV, Shoemaker RH, Paull RM, Tosini S, Skehan P, Scudiero DA, Monks A, Boyd MR. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1113. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh JS, Miwa GT. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2011;51:145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010510-100514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorleans A, Gigant B, Ravelli RBG, Mailliet P, Mikol V, Knossow M. PNAS. 2009;106:13775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904223106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbier P, Dorleans A, Devred F, Sanz L, Allegro D, Alfonso C, Knossow M, Peyrot V, Andreu JM. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:31672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.141929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mason RP, Zhao D, Liu L, Trawick L, Pinney KG. Integr Biol. 2011;3:375. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00135j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn BL, Gill GS, Grobelny DW, Chaplin JH, Paul D, Leske AF, Lavranos TC, Chalmers DK, Charman SA, Kostewicz E, Shackleford DM, Morizzi J, Hamel E, Jung MK, Kremmidiotis G. J Med Chem. 2011;54:6014. doi: 10.1021/jm200454y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd MR. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology Updates. J. B. Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1989. Status of the NCI preclinical antitumor drug discovery screen; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C, Langley J, Cronise P, Vaigro-Woiff A, Gray-Goodrich M, Campbell H, Mayo J, Boyd M. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1991;83:757. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houghton P, Fang R, Techatanawat I, Steventon G, Hylands PJ, Lee CC. Methods. 2007;42:377. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hamel E. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2003;38:1. doi: 10.1385/CBB:38:1:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin CM, Ho HH, Pettit GR, Hamel E. Biochemistry. 1989;28:6984. doi: 10.1021/bi00443a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]