Abstract

Background

Research has shown that interactions between young children’s temperament and the quality of care they receive predict the emergence of positive and negative socioemotional developmental outcomes. This multi-method study addresses such interactions, using observed and mother-rated measures of difficult temperament, children’s committed, self-regulated compliance and externalizing problems, and mothers’ responsiveness in a low-income sample.

Methods

In 186 30-month-old children, difficult temperament was observed in the laboratory (as poor effortful control and high anger proneness), and rated by mothers. Mothers’ responsiveness was observed in lengthy naturalistic interactions at 30 and 33 months. At 40 months, children’s committed compliance and externalizing behavior problems were assessed using observations and several well-established maternal report instruments.

Results

Parallel significant interactions between child difficult temperament and maternal responsiveness were found across both observed and mother-rated measures of temperament. For difficult children, responsiveness had a significant effect such that those children were more compliant and had fewer externalizing problems when they received responsive care, but were less compliant and had more behavior problems when they received unresponsive care. For children with easy temperaments, maternal responsiveness and developmental outcomes were unrelated. All significant interactions reflected the diathesis-stress model. There was no evidence of differential susceptibility, perhaps due to the pervasive stress present in the ecology of the studied families.

Conclusions

Those findings add to the growing body of evidence that for temperamentally difficult children, unresponsive parenting exacerbates risks for behavior problems, but responsive parenting can effectively buffer risks conferred by temperament.

Keywords: Difficult temperament, responsiveness, temperament×parenting interactions, compliance, externalizing behavior problems, ecological adversity

Disruptive, externalizing behavior problems in children and youths are important early markers of risk of future antisocial trajectories, leading to serious and widespread burdens for individuals, families, and societies. By contrast, children’s compliance, and particularly its committed, self-regulated form, has been broadly associated with positive, prosocial socioemotional outcomes. Several large bodies of research have led to a consensus that early biologically-founded temperamental characteristics and the qualities of early parent-child relationships both play important causal roles in emerging antisocial trajectories (e.g., Deater–Deckard, Dodge, Bates, & Pettit, 1998; Dodge, Coie, & Lynam, 2006; Gilliom & Shaw, 2004; Kiff, Lengua, & Zalewski, 2011; Lahey et al., 2008; Nigg, 2006; Frick & Morris, 2004; Shaw, Owens, Vondra, Keenan, & Winslow, 1996), as well as prosocial trajectories (e.g., Feldman, Greenbaum, & Yirmiya, 1999; Kim & Kochanska, 2012; Kochanska, 1995; Stifter, Spinrad, & Braungart-Rieker, 1999).

Children’s difficult temperament (anger proneness, negative emotionality, poor effortful control) is often seen as a biologically-based risk factor, a vulnerability, or diathesis that increases the probability of poor socioemotional outcomes (Bates, 1980; Eisenberg et al., 2000; 2009; Kim & Deater-Deckard, 2011; Kochanska, Barry, Jimenez, Hollatz, & Woodard, 2009; Lengua & Wachs, in press; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Sanson, Hemphill, & Smart, 2004). But we have also increasingly come to appreciate that child difficult temperament that encompasses high negative emotionality and poor self-regulation (Lengua & Wachs, in press) should be considered in interplay with early relationships with the caregivers. When exposed to negative, rejecting, unresponsive, harsh parenting, difficult children are at a considerable risk for a broad range of behavior problems: diminished compliance, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, or aggression. However, warm, responsive, authoritative parenting can effectively offset those risks (e.g., Bradley & Corwyn, 2008; Bates & Pettit, 2007; Bates, Pettit, Dodge, & Ridge, 1998; Belsky, Hsieh, & Crnic, 1998; Giliom & Shaw, 2004; Kim & Kochanska, 2012; Lerner, Nitz, Talwar, & Lerner, 1989; Messman et al., 2009; Rothbart & Bates, 2006; Stright, Gallagher, & Kelley, 2008; Thomas & Chess, 1977).

Belsky and colleagues (Belsky, 1997; Belsky & Pluess, 2009 a,b; Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & van IJzendoorn, 2007), as well as Boyce and Ellis (2005) and Ellis, Boyce, Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, and van Ijzendoorn (2011) have argued that such diathesis-stress approach does not adequately describe another important form of temperament-parenting interactions – differential susceptibility. They proposed that certain traits, including difficult temperament, should be seen as plasticity or malleability traits rather than risk factors. When subjected to adverse, sub-optimal parenting, temperamentally difficult children do have worse outcomes than easy children. But when raised by warm, responsive, authoritative parents, they can indeed do better than easy children.

The differential susceptibility model encompasses the traditional diathesis-stress effect, where difficult children who experience adverse parenting have worse outcomes than their easy peers and a plasticity effect, where difficult children who receive beneficial parenting may have better outcomes than their easy peers. Additionally, differential susceptibility model poses that easy children are less affected by a range of parenting qualities, adverse or beneficial, than difficult children. A growing literature has supported the presence of both types of interactions in predicting a broad range of developmental outcomes (Belsky & Pluess, 2009a, b; Ellis et al., 2011; Fowles & Kochanska, 2000; Kim & Kochanska, 2012; Kochanska, Kim, Barry, & Philibert, 2011). Belsky and Pluess (2009) called for including both negative and positive outcomes in analyses of such effects, and they indicated that differential susceptibility may be more easily revealed for the latter. This study addresses their recommendation. In addition to examining children’s externalizing behavior problems, we also include their committed compliance. Committed compliance is a wholehearted, eager, willing, enthusiastic form of compliance that appears to flow from “inside” and that does not require sustained parental control. Multiple studies have documented that committed compliance is a robust positive developmental hallmark (Kim & Kochanska, 2012; Kochanska, Aksan, & Koenig, 1995; Kochanska, Coy, & Murray, 2001).

We expand our past work on interactions between temperament and parenting, conducted with low-risk community families, to a population of low-income mothers and toddlers. Because economic disadvantage in itself is considered a risk factor for externalizing problems (Bornstein & Bradley, 2003; Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebanow, 1994; McLoyd, 1998), the understanding of risks, protective factors, vulnerability, and resilience in low-income families is particularly critical. Perhaps more important, very few, if any, studies to date have examined the issues of diathesis-stress versus differential susceptibility in an exclusively low-income sample. Ellis and colleagues (Ellis et al., 2011) specifically argued for studying such issues in broadly-ranging family ecologies. Economically disadvantaged families experience high levels of pervasive adversity and stress that may impact the form of interactions between vulnerability (or plasticity) factors, such as difficult temperament, and parenting in unknown ways.

We examine the interactions of children’s difficult temperament with maternal responsiveness, often considered as a key parenting dimension that can serve as a powerful protective factor (Pasalich et al., 2011; Pettit, Bates, & Dodge, 1997; Shaw, 2003; van den Boom, 1994). To assure robust, multi-method measurement, we employ lengthy behavioral observations of parenting in a variety of naturalistic contexts. Furthermore, we assess both children’s temperament and socioemotional outcomes using observational and mother-reported measures.

We focus on mothers and toddlers, because large bodies of literature have shown that both committed compliance and externalizing problems at toddler age are significant predictors of future developmental trajectories and adjustment (Kochanska et al., 1995; Shaw et al., 1996; Wakschlag, Tolan, & Leventhal, 2010). Throughout the analyses, we control for children’s gender, given the well-established gender differences in committed compliance and externalizing behavior problems (e.g., Crick & Zahn–Waxler, 2003; Kochanska et al., 2005).

Method

Participants

Mothers of young children volunteered in response to flyers distributed broadly in local communities, particularly in venues frequented by low-income families, such as Women, Infants, and Children nutritional program offices, thrift stores, Head Start locations, mobile homes parks, subsidized housing areas, etc. To be eligible, the mother had to receive or qualify for aid from a federal, state, or faith-based agency, or for Earned Income Tax Credit, the child had to be free of major health problems, and the mother able to speak English while observed.

After a screening telephone interview, 186 mothers of children (90 girls) aged from 24 to 44 months entered the study. The average annual family income was $20,385, SD = $13,010; 55% of mothers had no more than a high school education, and 45% had an associate, bachelors, or technical degree. There were 11% Hispanic, and 88% not Hispanic mothers; 73% White, 15% African American, 2% Asian, 2% American Indian, and 8% more than one race or unreported. In terms of marital status, 54% were married, 13% cohabitated, 31% were single or divorced, and 2% reported other arrangements.

Overview of design

Children’s difficult temperament was observed in the laboratory and rated by mothers at 30 months (M = 30.33, SD = 5.40); mothers’ responsiveness was observed twice, at 30 and 33 months (M = 33.34, SD = 5.48, N = 168, 81 girls); children’s committed compliance was observed, and externalizing problems were observed and rated by mothers at 40 months (M = 39.98, SD = 5.56, N = 162, 79 girls). A female visit coordinator (E) conducted the sessions, which were videotaped through a one-way mirror. Mothers signed informed consent forms prior to any procedures; the study has been annually reviewed and approved by the University of Iowa IRB. After the first assessment at 30 months was completed, mothers were randomized into two groups, and a parenting intervention was implemented. This article, however, reports the findings for the entire sample (there were no group differences in the reported constructs attributable to the intervention).

Multiple coding teams coded the behavioral data from the digital recordings. Typically, at least 15%–20% of cases were used for reliability. The coders realigned periodically to prevent drift. All behavioral measures have been designed or adapted in our laboratory and refined across several decades and multiple studies. We have programmatically implemented data aggregation to create robust constructs, as long as empirically justified (Rushton, Brainerd, & Pressley, 1983).

Measures of Children’s Difficult Temperament

Observed Measures

Anger

Children were observed in a scripted anger episode, “End of the Line”, from the Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery, Preschool Version (Goldsmith, Reilly, Lemery, Longley, & Prescott, 1993). Once the child became engaged with an interesting toy for about 1 min, E took the toy away and said: “I don’t want you to play with it.” E then held the toy out of child’s reach for 30 sec, and she replied “Not now” to the child’s efforts to get the toy back, while pretending to read a magazine. After 30 sec, E handed the toy back to the child, said that she decided it was OK for him/her to play with it, and apologized for having taken it away.

For every 5 sec segment, the presence of the child’s facial, bodily, and vocal anger expressions was coded (kappas, .81 – .89), and for the entire episode, overall intensity of anger was coded, from 0 (no anger), to 1 (mild anger), to 2 (moderate anger), to 3 (strong, intense anger), (kappa .79). Latency to the first anger expression was also coded, ICC, .99. Those scores, tallied where applicable, were standardized and aggregated into one anger score, M = .00, SD = .75, Cronbach alpha = .74

Effortful control

Children’s behavior was observed in four tasks, developed and refined in our laboratory (Kochanska, Murray, & Harlan, 2000; Kochanska et al., 2009) that called for suppressing the dominant response and performing a subdominant response: Snack Delay (waiting for candy, 4 trials), Tower (taking turns with E, 2 trials), Tongue (waiting to chew an M&M placed on tongue, 3 trials), and Gift (not peeking while E wrapped the gift and waiting to open it while E “went to get a bow”). The behavioral codes (available upon request) were straightforward and required little inference; higher codes reflected better effortful control. Reliability of coding across three teams was as follows: Snack Delay, kappas, .88- .91; Tower, ICCs, 1.00; Tongue, ICCs, .93 – .99; Gift-wrapping, ICCs .95 – .99; Gift-waiting, ICCs, .99 – 1.00. The scores were averaged across trials, where applicable, standardized, and averaged into one effortful control score, M = −.00, SD = .59, Cronbach’s alpha = .61.

Observed difficult temperament scores

Anger and effortful control scores correlated, r(185) = −.26, p < .001. Consequently, they were aggregated (after reversing the latter) into an observed difficult temperament score, M = .00, SD = .54.

Mother-Rated Measure

Mothers completed an abbreviated version of Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire (ECBQ, Putnam, Garstein, & Rothbart, 2006), a comprehensive temperament instrument, rating each item from 1 (never) to 7 (always). We included the following scales (Cronbach’s alphas in parentheses): Attention Focusing (.83), Discomfort (.74), Fear (.81), Frustration (.85), High Intensity Pleasure (.84), Impulsivity (.61), Inhibitory Control (.89), Low Intensity Pleasure (.75), Sadness (.80), Shyness (.85), Sociability (.84), and Soothability (.73). The scales’ scores were submitted to Principal Components Analysis (PCA). The first factor (Eigenvalue 3.24, 27% of variance) clearly reflected difficult temperament, with Sadness, Discomfort, Fear, Frustration, and Shyness loading positively, and Soothability and Inhibitory Control loading negatively. Consequently, the scores on that factor, M = .00, SD = 1.00, were used as mother-rated difficult temperament measures.

Observed and Mother-Rated Difficult Temperament Measures

The observed and mother-rated difficult temperament scores were unrelated (see Table 1). Consequently, we decide not to aggregate them, and to conduct the analyses separately for the two measures.

Table 1.

Correlations among Measures

| At 30 Months | At 30–33 Months | At 40 Months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C Difficult Temperament | M Responsiveness | C Committed | C Externalizing | ||

| Observeda | Mother-Ratedb | Compliance | Problemsc | ||

| C Difficult Temperament | |||||

| Observed | --- | .04 | −.21*** | −.38**** | .29**** |

| Mother-Rated | --- | −.18** | −.01 | .20*** | |

| M Responsiveness | --- | .21*** | −.27**** | ||

| C Committed Compliance | --- | −.43**** | |||

C = Child. M = Mother.

Composite of anger and reversed effortful control scores.

ECBQ difficult temperament factor score.

Composite of defiance in control contexts, ECI-4 Externalizing, ECI-4 Peer Aggression, and ITSEA Externalizing.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .025.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Measures of Mothers’ Responsiveness

Observed contexts

Mothers’ responsiveness to their children was observed twice, during the laboratory sessions at 30 and 33 months, in naturalistic yet scripted contexts, such as play, snack, chores, free time, or mother busy (seven contexts, total of 62 min per session; overall, 14 contexts and 124 min).

Coding and data aggregation

The coders rated responsiveness for each context from 1 (highly unresponsive) to 7 (highly responsive). The coding was adapted from Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, and Wall (1978); one judgment integrated Ainsworth’s original scales of sensitivity-insensitivity, acceptance-rejection, and cooperation-interference. Reliability (intra-class correlations, ICCs) across six teams of coders ranged from .81 to .93.

The scores across all contexts cohered: Cronbach’s alphas were .89 at 30 months and .87 at 33 months. Consequently, they were aggregated into one score at each time, M = 4.55, SD = 1.07 and M = 4.58, SD = 1.04, respectively. Those scores correlated, r (168) = .81, p < .001, and were standardized and aggregated into an overall maternal responsiveness score, M = −.03, SD = .95.

Measures of Children’s Socioemotional Outcomes: Committed Compliance and Externalizing Behavior Problems

Committed Compliance: Observed Measure

Observed contexts

During the laboratory session at 40 months, we observed children’s committed, self-regulated compliance toward their mothers in naturalistic yet scripted control contexts (cleaning up toys, 10 min, and not touching easily accessible, very attractive, prohibited objects, 45 min), for the total of 55 min.

Coding and data aggregation

Child committed compliance was defined as self-regulated, wholehearted, eager compliance with maternal requests and prohibitions that did not seem to require maternal control. It was coded, for example, in the toy cleanup, when the child eagerly, even enthusiastically picked up the toys, moving spontaneously from one pile to another; in the prohibition context, when he or she looked at the prohibited toys without touching; turned away from them; shook head, saying “we don’t touch these”. It was coded for every 30 sec segment. Reliability, kappas, across six teams of coders, ranged from .69 to .92 (the codes included committed compliance, defiance, and several other behaviors, not considered here)..

All instances of child committed compliance were tallied and divided by the number of coded segments for the toy cleanup, M = .28, SD = .28, and for the prohibited objects context, M = .80, SD = .19. Those two scores were standardized and averaged into one committed compliance score, M = .00, SD = .78.

Externalizing Behavior Problems: Observed Measure

Observed contexts

During the laboratory session at 40 months, we observed children’s defiance toward their mothers in the same control contexts as above (toy cleanup, prohibited objects), for the total of 55 min.

Coding and data aggregation

Child defiance, defined as aversive noncompliance, accompanied by a temper tantrum, deliberate intensification of noncompliant behavior, hitting mother, throwing or kicking toys, whining, etc., was also coded for every 30 sec segment. Reliability was reported above.

All instances of child defiance were tallied and divided by the number of coded segments for the toy cleanup, M = .04, SD = .13, and for the prohibited objects context, M = .02, SD = .05. Those two scores were standardized and averaged into one defiance score, M = .00, SD = .81.

Externalizing Behavior Problems: Mother-Rated Measures

Early Childhood Inventory

(ECI-4, Gadow & Sprafkin, 2000). Mothers completed the ECI-4, a well-established clinical instrument for children aged 3–5. Using the Symptom Severity scoring approach, where most items are rated as 0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = often, or 3 = very often, we created a score for Externalizing Behavior Problems, M = 6.39, SD = 5.82. This score was the sum of items targeting Oppositional Defiant Disorder, M = 5.17, SD = 4.23, and Conduct Disorder, M = 1.22, SD = 2.17. We also used the Peer Conflict Scale that targets peer aggression, M = 2.90, SD = 3.13.

Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment

(ITSEA; Carter, Briggs-Gowan, Jones, & Little, 2003). Mothers completed the ITSEA, another very well-established instrument, rating each item as 0 (Not true/rarely), 1 (Somewhat true/sometimes), or 2 (Very true/often). We used the overall score for the Externalizing Domain, M = .54, SD = .27, that encompasses the means of the scales of Impulsivity, M = .79, SD = .37, Aggression/Defiance, M = 56, SD =.31, and Peer Aggression, M = .26, SD = .26.

Mother-rated disruptive, externalizing behavior

The three scores were highly correlated (rs ranging from .68 to .76, all ps < .001), and consequently, they were standardized and aggregated into one mother-rated externalizing behavior score, M = .00, SD = .90.

Overall Measure of Externalizing Behavior Problems

The observed and mother-rated externalizing behavior scores were correlated, r(162) = .19, p < .025. Consequently, they were aggregated into one overall externalizing behavior problems score, M = .00, SD = .66. When the internal consistency of the four components (defiance, ECI-4 Externalizing Behavior Problems and Peer Conflicts, and ITSEA Externalizing Domain) was examined, Cronbach’s alpha was .78.

Results

Preliminary analyses

We examined the correlations among the studied constructs. Those are presented in Table 1.

By and large, the correlations were in the predicted directions, significant but modest. Children’s difficult temperament was associated with maternal lower responsiveness, and with more externalizing behavior problems and, for observed temperament measure, less committed compliance 10 months later. Higher responsiveness was associated with more committed compliance and fewer externalizing problems. The two outcomes, committed compliance and externalizing problems, were negatively related. The observed and mother-rated measures of difficult temperament were unrelated.

Children’s temperament as a moderator of the links between mothers’ responsiveness and children’s socioemotional outcomes

We conducted four hierarchical multiple regression analyses, two with committed compliance and two with externalizing problems as dependent variables. For each outcome, one equation employed observed and one employed mother-rated difficult temperament scores as predictors. The findings are in Table 2.

Table 2.

Child Difficult Temperament at 30 Months as a Moderator of Links between Maternal Responsiveness at 30-33 Months and Children’s Socioemotional Outcomes at 40 Months

| Socioemotional Outcome Measures | ||

|---|---|---|

| Predictors | C Committed Compliance | C Externalizing Problemsa |

| C Gender | −.23*** | .20** |

| C Observed Difficult Temperament b | −.33**** | .26**** |

| M Responsiveness | .11 | –.18** |

| C Observed Difficult Temperament × M Responsiveness | .18** | −.27**** |

| C Gender | −.31**** | .27*** |

| C Mother-Rated Difficult Temperament c | − .01 | .20*** |

| M Responsiveness | .18** | −.19** |

| C Mother-Rated Difficult Temperament × M Responsiveness | .08 | −.20*** |

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .025.

p < .01.

p < .001.

The numbers are standardized regression coefficients in the final equations.

Composite of defiance in control contexts, ECI-4 Externalizing, ECI-4 Peer Aggression, and ITSEA Externalizing.

Composite of anger and reversed effortful control scores

ECBQ difficult temperament factor score.

In each regression, child gender was entered in Step 1 (girl=0, boy=1), child difficult temperament (observed or mother-rated) and maternal responsiveness in Step 2, and the interaction of difficult temperament and responsiveness in Step 3. Table 2 presents standardized regression coefficients for the final equations, with all the predictors entered.

In all equations, gender emerged as a significant predictor, with boys having lower scores on committed compliance and higher scores on disruptive, externalizing measures, consistent with a large body of evidence in the field. In three equations, difficult temperament, regardless of its assessment method, significantly moderated the effects of maternal responsiveness on the outcomes (the only exception was the equation predicting committed compliance from mother-rated difficult temperament and responsiveness, where the interaction was not significant).

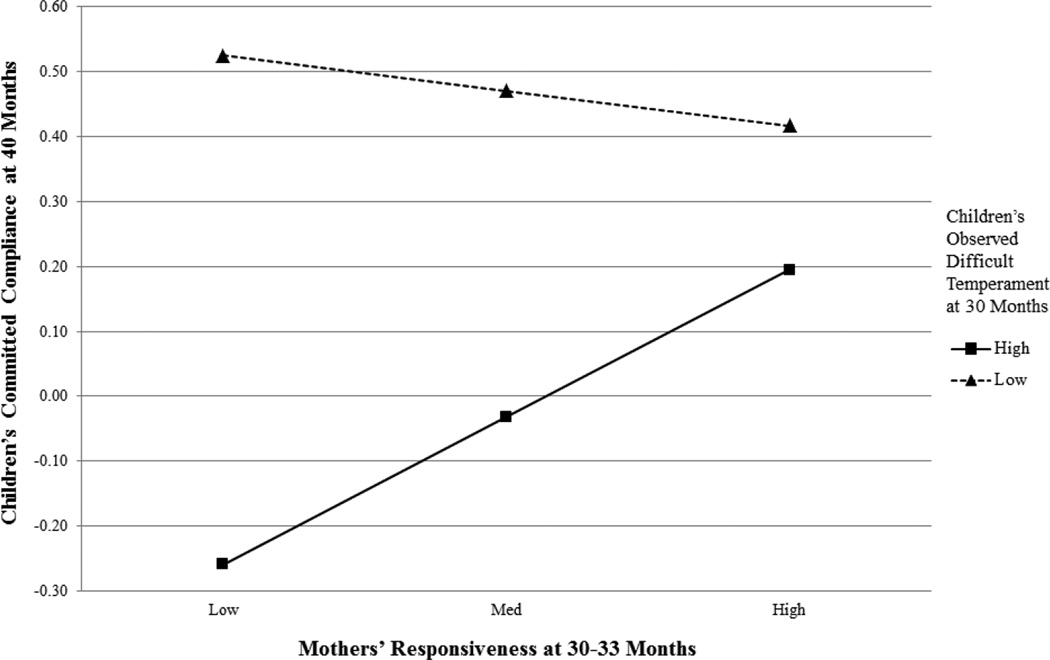

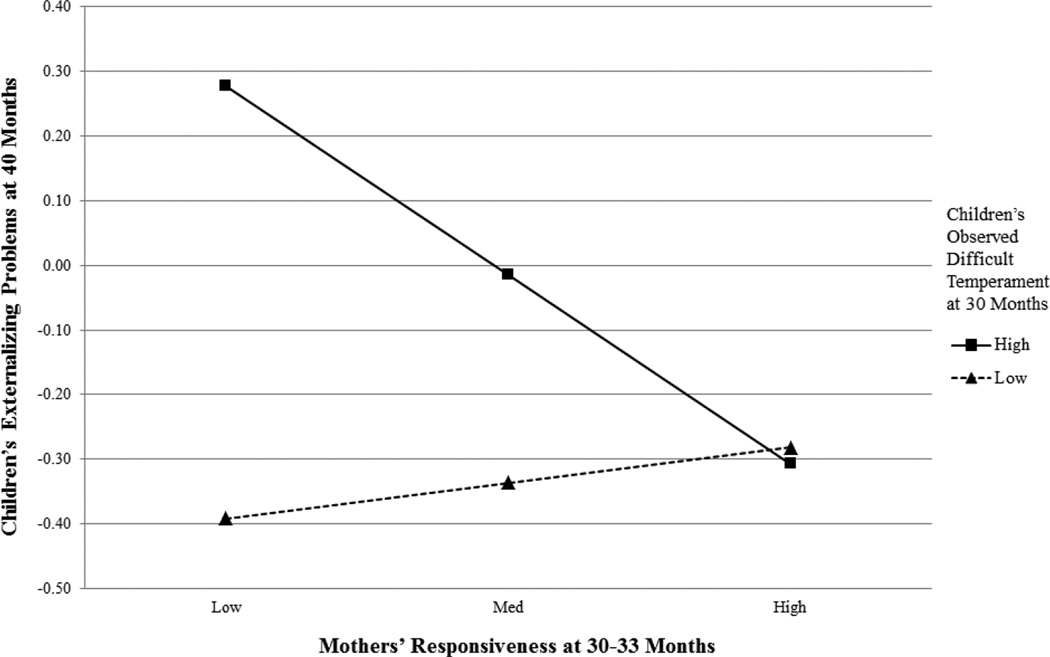

We followed up the three significant interaction effects with the simple slopes analyses (Aiken & West, 1991). Figures 1–3 present the findings.

Figure 1.

Children’s observed difficult temperament at 30 months moderates the effect of mothers’ responsiveness at 30–33 months on children’s committed compliance at 40 months. Child’s gender was a covariate (not depicted). Solid line represents significant simple slope; dashed line represents non-significant simple slope.

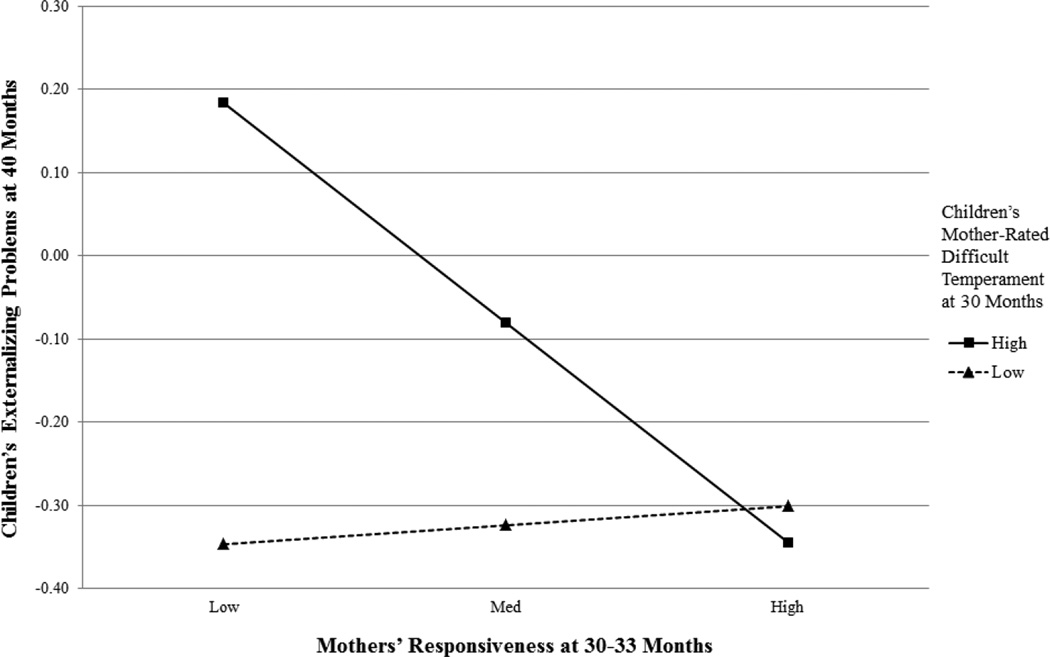

Figure 3.

Children’s mother-rated difficult temperament at 30 months moderates the effect of mothers’ responsiveness at 30–33 months on children’s externalizing problems at 40 months. Child’s gender was a covariate (not depicted). Solid line represents significant simple slope; dashed line represents non-significant simple slope.

Figure 1 depicts children’s observed difficult temperament as the moderator of the effect of mothers’ responsiveness on children’s committed compliance. The simple slope for children who were highly difficult (1 SD above the mean) was significant, b = .24, SE = .08, p < .005, but for those who were temperamentally easy (1 SD below the mean) it was not, b = −.06, SE = .09, ns. The increase in mothers’ responsiveness was significantly associated with children’s increased committed compliance among the highly difficult children, but responsiveness was unrelated to committed compliance among the easy children. The interaction was clearly consistent with the diathesis-stress model: A combination of difficult temperament and unresponsive parenting resulted in very low committed compliance, but responsive parenting served to offset that risk (although even with responsive mothers, difficult children did not surpass their easy peers). .

Figure 2 depicts children’s observed difficult temperament as the moderator of the effect of mothers’ responsiveness on children’s externalizing problems. Again, the simple slope for the highly difficult children was significant, b = −.31, SE = .07, p < .001, but for the easy children it was not, b = .06, SE = .07, ns. Among the difficult children, the increase in mothers’ responsiveness was associated with significant decrease in children’s externalizing problems, whereas among the easy children, variations in responsiveness were unrelated to behavior problems. In this case, the interaction again was clearly consistent with the diathesis-stress model. The difficult children who received unresponsive parenting had very poor outcomes, but those who received responsive parenting were no different than the easy children (but did not do better than the easy children).

Figure 2.

Children’s observed difficult temperament at 30 months moderates the effect of mothers’ responsiveness at 30–33 months on children’s externalizing problems at 40 months. Child’s gender was a covariate (not depicted). Solid line represents significant simple slope; dashed line represents non-significant simple slope.

Figure 3 depicts children’s mother-rated difficult temperament as the moderator of the effects of mothers’ responsiveness on children’s externalizing problems. Again, for highly difficult children, the simple slope was significant, b = −.28, SE = .07, p < .001, but for the easy children it was not, b = .02, SE = .08, ns. The increase of mothers’ responsiveness was associated with a significant decrease in externalizing problems among the difficult children, but the variations in responsiveness were unrelated to behavior problems for easy children. The interaction was again consistent with the diathesis-stress model. The difficult children with unresponsive mothers had very poor outcomes, but high maternal responsiveness offset those risks. Difficult children with responsive mothers did no worse (but not better) than their easy peers.

Discussion

This research makes several positive contributions. It dovetails with and replicates several existing studies, further enriching our understanding of the interplay between temperament and parenting in developmental psychopathology. The study has several strengths, compared to the extant recent work. For example, we replicated and extended the findings by a research program in the Netherlands (Messman et al., 2009; van Zejil et al., 2007), who investigated child difficult temperament as moderator of the effects of mothers’ parenting on children’s externalizing problems and also found difficult children to be more susceptible. Van Zeijl et al. (2007) andMessman et al. (2009) relied on mother-reported measures of difficult temperament, relatively short observations of parenting, used a highly demographically homogeneous sample of families, and screened children to select those with elevated behavior problems. We assessed child difficult temperament using both reports and observations, observed parenting in lengthy, repeated sessions, recruited a highly diverse, economically stressed group of families, and did not screen the children for anything other than the absence of serious physical illnesses. Despite those differences, their and our findings are strikingly consistent.

Several investigations examined the data from NICHD Study of Early Child Care with regard to interactions between temperament and parenting (Bradley & Corwyn, 2008; Stright et al., 2008). Those two studies have found significantly stronger relations between parenting, including sensitivity, and children’s outcomes, including externalizing behavior, for children who had been temperamentally difficult as infants than for those who had been easy. But in both those studies, infants’ temperament and later outcomes were based on ratings (parents and teachers, respectively). Our study replicated those interactions, using both observed and reported measures of temperament and outcomes.

The findings are also consistent with research on the interplay of biology and early care in development that includes both human and animal studies. Individuals who have high-risk genotypes (e.g., a short 5-HTTLPR allele) develop a host of problems if they also experience adverse or sub-optimal parenting, but with favorable parenting, they have no worse outcomes than individuals without such genotype (Belsky et al., 2007; Belsky & Pluess, 2009a, b; Barry, Kochanska, & Philibert, 2008; Champoux et al., 2002; Sonuga-Barke et al., 2009; Suomi, 2006).

The inclusion of both positive (committed compliance) and negative (behavior problems) socioemotional outcomes is also a strength of this study. The original intention was to explore whether, for the positive outcome, the difficult temperament×parenting interactions would be more likely to conform to the differential susceptibility model whereas for the negative outcome, they would be more likely to reflect the diathesis-stress model (Belsky & Pluess, 2009). We found, however, that all three significant interactions (observed difficult temperament and committed compliance, observed and mother-rated difficult temperament and behavior problems) were clearly consistent with the diathesis-stress or dual-risk model.

We believe that this pattern of results may be due to the nature of our sample, where persistent adversity and stress were key aspects of the families’ ecological niche. It is entirely possible that the high, pervasive, multi-dimensional stress impinging on the families limited the extent of potential beneficial effects of positive parenting. Maternal responsiveness did serve as a protective factor, but only to the point of erasing risks for temperamentally vulnerable children, but not to the point of enabling them to surpass their less vulnerable peers (differential susceptibility). Perhaps for the latter effects to occur, parents and children need to live in a context of a more optimal ecological niche and to have access to more resources than the families in the current study. Indeed, while examining similar constructs (negative emotionality, positive parenting, children’s committed compliance) in a low-risk community sample, we did find differential susceptibility effects (Kim & Kochanska, 2012).

Note that most of the extant research on differential susceptibility has been carried out with community families. None of the studies in the review by Belsky and Pluess (2009) on interactions between difficult temperament and parenting was conducted with exclusively high-risk or demographically stressed families.Ellis et al. (2011) urged researchers to consider the ecological or cultural context in future research on person-environment interactions. To have examined such processes in an exclusively low-income sample is a contribution of our study. Researchers studying differential susceptibility and diathesis-stress should be encouraged to include samples that are even more diverse and stressed than the current one (e.g., predominantly minority, single parents, living in inner cities), as well as children selected for elevated behavior problems.

An important future question concerns the mechanisms responsible for the significant links between maternal responsiveness and behavior problems that have repeatedly been found for temperamentally difficult children. One possibility is that sensitive parenting provides important supports for the child’s emotion regulation (Sroufe, 1996), and thus, it may be especially consequential for temperamentally difficult children. A compromised capacity to regulate arousal and emotions has been typically seen as a key characteristic of difficult temperament, as well as a factor in the origin of antisocial behavior (Calkins & Keane, 2009). Another important future direction involves the examination of interactions between difficult temperament and maternal care repeatedly over time, given the mutual and transactional nature of processes in mother-child dyads (e.g., Lipscomb et al., 2011).

In summary, this study contributes to the growing literature on the interplay of biological risk and parenting factors in the development of psychopathology in families living under conditions of adversity. Future systematic research will further consolidate our understanding of basic processes of development and it will inform parenting intervention and prevention programs, by helping us target at-risk children who can most benefit from optimal care.

It has been long known that child difficult temperament and maternal parenting interact to predict future socioemotional outcomes, but the specific forms of those interactions continue to receive intense scrutiny.

We examined toddlers’ difficult temperament as a moderator of the effects of mothers’ responsiveness on children’s committed compliance and externalizing behavior problems using a short-term longitudinal design in a low-income sample. The measures combined observations in laboratory paradigms and naturalistic interactions, and maternal reports.

For difficult toddlers, responsiveness had a significant effect such that those children were more compliant and had fewer externalizing problems when they received responsive care, but were less compliant and had more problems when they received unresponsive care.

The interactions were consistent with the diathesis-stress model. The absence of differential susceptibility effects may have been due to the nature of the sample.

The findings are clinically relevant because they inform prevention research: Parent-child dyads with temperamentally difficult toddlers should be targeted for parenting interventions.

Acknowledgements

This study has been funded by the grants from NIMH, R01 MH63096 and from NICHD, R01 HD069171-11, and by Stuit Professorship to Grazyna Kochanska. We thank many students and staff members for their help with data collection, coding, and file creation, including Lea Boldt, Jamie Koenig Nordling, Jarilyn Akabogu, Jessica O’Bleness, Jeung Eun Yoon, and Robin Barry, all mothers and children in Play Study for their enthusiastic commitment, and Rick Hoyle for methodological advice.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS, Blehar MC, Waters E, Wall S. Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE. The concept of difficult temperament. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 1980;26:299–319. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS. Temperament, parenting, and socialization. In: Grusec JE, Hastings PD, editors. Handbook of Socialization: Theory and research. New York: Guilford; 2007. pp. 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bates JE, Pettit GS, Dodge KA, Ridge B. Interaction of temperamental resistance to control and restrictive parenting in the development of externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:982–95. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.5.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry RA, Kochanska G, Philibert RA. G x E interactions in the organization of attachment: Mothers’ responsiveness as a moderator of children’s genotypes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:1313–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Variation in susceptibility to rearing influences: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry. 1997;8:182–186. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. For better and for worse: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:300–304. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Hsieh KH, Crnic K. Mothering, fathering, and infant negativity as antecedents of boys’ externalizing problems and inhibition at age 3 years: Differential susceptibility to rearing experience? Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:301–319. doi: 10.1017/s095457949800162x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009a;135:885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. The nature (and nurture?) of plasticity in early human development. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2009b;4:345–351. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01136.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce WT, Ellis BJ. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary–developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:271–301. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Bradley RH, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Infant temperament, parenting, and externalizing behavior in first grade: a test of the differential susceptibility hypothesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2008;49:124–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Keane SP. Developmental origins of early antisocial behavior. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21:1095–1109. doi: 10.1017/S095457940999006X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Jones SM, Little TD. The Infant–Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2003;31:495–514. doi: 10.1023/a:1025449031360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champoux M, Bennett A, Shannon C, Higley JD, Lesch KP, Suomi SJ. Serotonin transporter gene polymorphism, differential early rearing, and behavior in rhesus monkey neonates. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002;7:1058–1063. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Zahn–Waxler C. The development of psychopathology in females and males: Current progress and future challenges. Development and Psychopathology. 2003;15:719–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater–Deckard K, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS. Multiple risk factors in the development of externalizing behavior problems: Group and individual differences. Development and Psychopathology. 1998;10:469–493. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Coie JC, Lynam D. Aggression and antisocial behavior in youth. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology, Social, emotional, and personality development. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 719–788. (Series Eds.), (Volume Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65:296–318. 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Boyce WT, Belsky J, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH. Differential susceptibility to the environment: An evolutionary–neurodevelopmental theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:7–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Guthrie IK, Fabes RA, Shepard S, Losoya S, Murphy B, Jones S, Poulin R, Reiser M. Prediction of elementary school children’s externalizing problem behaviors from attentional and behavioral regulation and negative emotionality. Child Development. 2000;71:1367–1382. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Spinrad TL, Cumberland A, Liew J, Reiser M, Zhou Q, Losoya SH. Longitudinal relations of children’s effortful control, impulsivity, and negative emotionality to their externalizing, internalizing, and co-occurring behavior problems. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:988–1008. doi: 10.1037/a0016213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Greenbaum CW, Yirmiya N. Mother-infant affect synchrony as an antecedent of the emergence of self-control. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35(5):223–231. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC, Kochanska G. Temperament as a moderator of pathways to conscience in children: The contribution of electrodermal activity. Psychophysiology. 2000;37:788–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Morris, A S. Temperament and developmental pathways to conduct problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:55–68. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Sprafkin J. Early Childhood Inventory-4: Screening manual. Stony Brook, NY: Checkmate Plus; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:313–333. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith HH, Reilly J, Lemery KS, Longley S, Prescott A. Preliminary manual for the Preschool Laboratory Temperament Assessment Battery (version 1.0). Technical Report. Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kiff CJ, Lengua LJ, Zalewski M. Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:251–301. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Deater-Deckard K. Dynamic changes in anger, externalizing and internalizing problems: attention and regulation. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:156–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Kochanska G. Child temperament moderates effects of parent-child mutuality on self-regulation: A relationship-based path for emotionally negative infants. Child Development. 2012;83:1275–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01778.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G. Children's temperament, mothers' discipline, and security of attachment: Multiple pathways to emerging internalization. Child Development. 1995;66:597–615. [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Aksan N, Koenig AL. A longitudinal study of the roots of preschoolers' conscience: Committed compliance and emerging internalization. Child Development. 1995;66:1752–1769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Barry RA, Jimenez NB, Hollatz AL, Woodard J. Guilt and effortful control: Two mechanisms that prevent disruptive developmental trajectories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:322–333. doi: 10.1037/a0015471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Coy KC, Murray KT. The development of self-regulation in the first four years of life. Child Development. 2001;72:1091–1111. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Kim S, Barry RA, Philibert RA. Children’s genotypes interact with maternal responsive care in predicting children’s competence: Diathesis-stress or differential susceptibility? Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:605–616. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan E. Effortful control in early childhood: Continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36:220–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Van Hulle CA, Keenan K, Rathouz PJ, D’Onofrio BM, Rodgers JL, Waldman ID. Temperament and parenting during the first year of life predict future child conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:1139–1158. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9247-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lengua JJ, Wachs TD. Temperament and risk: Resilient and vulnerable responses to adversity. In: Zentner M, Shiner R, editors. Handbook of temperament. NY: Guilford Press; (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JV, Nitz K, Talwar R, Lerner RM. On the functional significance of temperamental individuality: A developmental contextual view of the concept of goodness of fit. In: Kohnstamm GA, Bates JE, Rothbart MK, editors. Temperament in childhood. West Sussex: Wiley; 1989. pp. 509–522. [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb ST, Leve LD, Harold GT, Neiderhiser JM, Shaw DS, Ge X, Reiss D. Trajectories of parenting and child negative emotionality during infancy and toddlerhood: A longitudinal analysis. Child Development. 2011;82:1661–1675. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesman J, Stoel R, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, Juffer F, Koot HM, Alink LRA. Predicting growth curves of early childhood externalizing problems: Differential susceptibility of children with difficult temperament. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:625–636. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9298-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT. Temperament and developmental psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:395–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasalich DS, Dadds MR, Hawes DJ, Brennan J. Do callous-unemotional traits moderate the relative importance of parental coercion versus warmth in child conduct problems? An observational study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011;52:1308–1315. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Supportive parenting, ecological contexts, and children’s adjustment: A seven-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 1997;68:908–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1997.tb01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam SP, Gartstein MA, Rothbart MK. Measurement of fine-grained aspects of toddler temperament: The Early Childhood Behavior Questionnaire. Infant Behavior & Development. 2006;29:386–401. doi: 10.1016/j.infbeh.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart MK, Bates JE. Temperament. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 99–166. (Series Eds.), (Volume Ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JP, Brainerd CJ, Pressley M. Behavioral development and construct validity: The principle of aggregation. Psychological Bulletin. 1983;94:18–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sanson A, Hemphill SA, Smart D. Connections between temperament and social development: A review. Social Development. 2004;13:142–170. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS. Innovative approaches and methods to the study of children's conduct problems. Social Development. 2003;12:309–313. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Owens EB, Vondra JI, Keenan K, Winslow EB. Early risk factors and pathways in the development of early disruptive behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1996;8:679. [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, Oades RD, Psychogiou L, Chen W, Barbara Franke B, Buitelaar J, Banaschewski T, Ebstein RP, Gil M, Anney R, Miranda A, Roeyers H, Rothenberger A, Sergeant J, Steinhausen HC, Thompson M, Asherson P, Faraone SV. Dopamine and serotonin transporter genotypes moderate sensitivity to maternal expressed emotion: the case of conduct and emotional problems in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1052–1063. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe A. Emotional development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stifter CA, Spinrad TL, Braungart-Rieker JM. Toward a developmental model of child compliance: The role of emotion regulation in infancy. Child Development. 1999;70:21–32. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stright AD, Gallagher KC, Kelley K. Infant temperament moderates relations between maternal parenting in early childhood and children’s adjustment in first grade. Child Development. 2008;79:186–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomi SJ. Risk, resilience, and gene × environment interactions in rhesus monkeys. Annals of New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1094:52–62. doi: 10.1196/annals.1376.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A, Chess S. Temperament and development. New York: Brunner/Mazel; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- van den Boom DC. The influence of temperament and mothering on attachment and exploration: An experimental manipulation of sensitive responsiveness among lower-class mothers with irritable infants. Child Development. 1994;65:1457–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zeijl J, Mesman J, Stolk MN, Alink RAL, van IJzendoorn MH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Juffer F, Koot HM. Differential susceptibility to discipline: The moderating effect of child temperament on the association between maternal discipline and early childhood externalizing problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:626–636. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakschlag LS, Tolan PH, Leventhal BL. Research Review: ‘Ain’t misbehavin’: Towards a developmentally-specified nosology for preschool disruptive behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:3–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]