Abstract

MYH9-related disease (MYH9-RD) is a rare autosomal dominant syndromic disorder caused by mutations in MYH9, the gene encoding for the heavy chain of non-muscle myosin IIA (myosin-9). MYH9-RD is characterized by congenital macrothrombocytopenia and typical inclusion bodies in neutrophils associated with a variable risk of developing sensorineural deafness, presenile cataract, and/or progressive nephropathy. The spectrum of mutations responsible for MYH9-RD is limited. We report five families, each with a novel MYH9 mutation. Two mutations, p.Val34Gly and p.Arg702Ser, affect the motor domain of myosin-9, whereas the other three, p.Met847_Glu853dup, p.Lys1048_Glu1054del, and p.Asp1447Tyr, hit the coiled-coil tail domain of the protein. The motor domain mutations were associated with more severe clinical phenotypes than those in the tail domain.

Keywords: MYH9-related disease, MYH9 gene, Mutational screening, Missense mutation, In frame deletion/duplication, Genotype–phenotype correlation

1. Introduction

MYH9-related disease (MYH9-RD) is an autosomal-dominant disorder characterized by thrombocytopenia, giant platelets and inclusion bodies in neutrophils deriving from the aggregation of mutant and wild type proteins [1–3]. In addition to the hematological features, patients can develop, during infancy or adult life, sensorineural hearing loss, presenile cataract and/or proteinuric nephropathy that often leads to end-stage renal disease [4,5]

MYH9-RD is caused by mutations of MYH9, the gene encoding for the heavy chain (myosin-9) of the isoform A of the non-muscle myosin of class II [6,7]. Class II myosins are hexameric complexes consisting of two heavy chains and two pairs of light chains. Each heavy chain contains a N-terminal globular head or motor domain, a long alpha-helix coiled-coil tail domain, and a short C-terminal non-helical tailpiece. The spectrum of mutations identified in the MYH9 gene is limited, consisting of 44 different alterations, mainly amino acids substitutions, hitting only 35 of the 1960 residues of myosin-9. In fact, residues Ser96 or Arg702 of the globular head, and Arg1165, Asp1424, or Glu1841 of the coiled coil domain, or Arg1933 of the non-helical tailpiece are mutated in 79% of the reported families. The remaining alterations are private or detected in a few cases [2].

Genotype/phenotype studies have been reported showing that individuals with mutations in the motor domain of myosin-9 have more severe thrombocytopenia and higher risk of developing nephropathy and deafness [8–10]. Conversely, mutations in the tail domain are associated with a milder phenotype characterized by slight to moderate thrombocytopenia and a lower prevalence of extra-hematological manifestations.

In this paper, we report the identification of five novel mutations, three missense variations in exons 1, 16, and 30, and two in frame alterations of exons 20 and 24, thus extending the spectrum of mutations associated with MYH9-RD. The patients from these pedigrees presented with phenotypes consistent with the results of previous genotype/phenotype studies.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patients

Family 1. The proband (II-1; Table 1 and Fig. 1) was an 11-year-old boy referred for diagnostic investigation of familial thrombocytopenia. Since his mother had reduced platelet count he previously received a diagnosis of Bernard–Soulier syndrome. His platelet count was 60 × 109/L without bleeding history. Examination of peripheral blood smears after conventional staining demonstrated giant platelets and Döhle-like basophilic inclusions in neutrophil granulocytes. In vitro functional studies (Born's method) showed normal platelet aggregation after stimulation with ADP, collagen, and ristocetin. At re-evaluation, his 52-years-old mother had 30 × 109/L platelets, no bleeding diathesis, and a history of bilateral hearing loss since the age of 40. Also the proband's aunt (age 59 years) had thrombocytopenia without history of bleeding. Both proband's relatives presented giant platelets and Döhle-like inclusions. The search for extra-hematological manifestations revealed severe bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (intermediate and high frequencies) in both the adult family members and bilateral cataract in the proband's aunt. No other complications were found, in particular none of the affected subjects presented significant proteinuria.

Table 1.

Main clinical and molecular features of nine MYH9-RD patients with five novel MYH9 mutations.

| Family/patient | Age/gender | Platelet count (×109/L)a | Giant platelets/leukocyte inclusionsb | Bleeding timec | Bleeding diathesis | Proteinuria/renal failure | Sensorineural hearing lossd | Cataracte | Mutationf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/I-1 | 52/F | 30 | Yes/yes | Normal | None | No/no | Bilateral | No | c.101T > G (p.Val34Gly) |

| 1/I-2 | 59/F | 40 | Yes/yes | Normal | None | No/no | Bilateral | Bilateral | |

| 1/II-1 | 11/M | 72 | Yes/yes | Normal | None | No/no | No | No | |

| 2/II-1 | 44/M | 25 | Yes/yes | Increased | Easy bruising, epistaxis, bleeding after teeth extraction | Yes/no | Bilateral | No | c.2104C > A (p.Arg702Ser) |

| 3/I-2 | 33/F | 85 | Yes/yes | nd | Easy bruising, menorrhagia, epistaxis | No/no | No | No | c.2539_2559dup (p.Met847_Glu853dup) |

| 3/II-1 | 2/M | 96 | Yes/yes | nd | None | No/no | No | nd | |

| 4/I-1 | 43/M | 116 | Yes/yes | Increased | Easy bruising, gum bleeding | No/no | Bilateral (mild) | No | c.3142_3162del (p.Lys1048_Glu1054del) |

| 4/II-1 | 8/F | 123 | Yes/yes | Increased | Epistaxis, bleeding after surgery and loss of one milk tooth | No/no | No | No | |

| 5/I-1 | 20/F | 65 | Yes/yes | nd | Easy bruising, epistaxis | No/no | No | No | c.4339G > T (p.Asp1447Tyr) |

nd, not determined.

Assessed by phase contrast microscopy. In MYH9-RD, the actual platelet count can be determined only by microscopic counting because automatic cell counters do not recognize giant platelets and therefore greatly underestimate platelet count (ref. [1]).

Evaluated by examination of peripheral blood smears.

Evaluated according to the Ivy method.

Evaluated by audiometric examination.

Evaluated by ophthalmological examination.

Nucleotide A of the ATG translation initiation start site of the MYH9 cDNA (GenBank sequence NM_002473.3) is indicated as nucleotide +1.

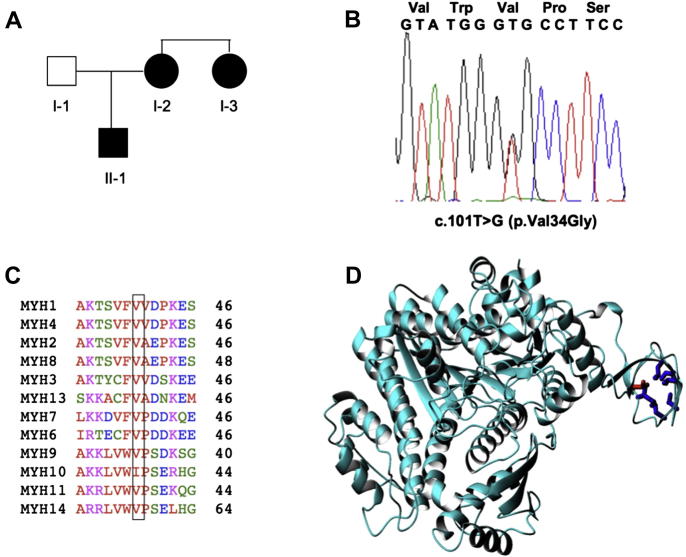

Fig. 1.

Identification of the p.Val34Gly mutation in family 1. A) Family pedigree; B) Direct sequencing of PCR products of exon 1 demonstrates two overlapping peaks of the heterozygous c.101T > G mutation; C) Alignment of all human muscle and non-muscle myosins of class II with the conserved residues boxed. MYH1 (NM_005963), MYH4 (NM_017533), MYH2 (NM_017534), MYH8 (NM_002472), MYH3 (NM_002470), MYH13 (NM_003802), MYH7 (MN_000257), MYH6 (NM_002471), MYH9 (AB191263), MYH10 (NM_005964), MYH11 (NM_002474), and MYH14 (AY165122); D) Ribbon structure of the smooth muscle myosin motor domain (1br2). The side chain of Val34 (in the pdb numbering Val37) is indicated in red. The side chains of surrounding hydrophobic residues (I49, V57, V59, L61, L70 and I75) are shown in blue.

Family 2. The proband (II-1; Table 1 and Fig. 2) was a 44-year-old male referred for thrombocytopenia (platelet count 25 × 109/L) discovered at the age of 3 years when he underwent tonsillectomy complicated by prolonged bleeding. He presented with easy bruising, recurrent epistaxis, and bleeding after tooth extractions despite prophylaxis with platelet transfusions. He also had severe bilateral sensorineural hearing loss, with onset at the age of 7 years and a rapidly progressive evolution to complete deafness. At the age of 12 years he was diagnosed as having immune thrombocytopenia and received steroids for two years without any significant improvement of the platelet count. When he was 17-years-old, the diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia was confirmed and he underwent splenectomy without any increase in platelet count. Thereafter, he received further courses of steroids, vincristine, and cyclophosphamide, with any improvements, until the age of 21 when he refused any further treatments. He had no familial history of thrombocytopenia or major bleeding episodes. Our laboratory work-up demonstrated giant platelets and typical Döhle-like bodies in neutrophil granulocytes at examination of peripheral blood smear. Flow cytometry showed normal expression of the glycoproteins Ib-IX-V, IIb-IIIa, and Ia-IIa on the platelet surface; in vitro aggregation studies were not performed because of the low platelet count. Screening for kidney function revealed relevant proteinuria (2.2 gr/24 h) and normal serum creatinine, while ophthalmological evaluation returned normal results (Table 1).

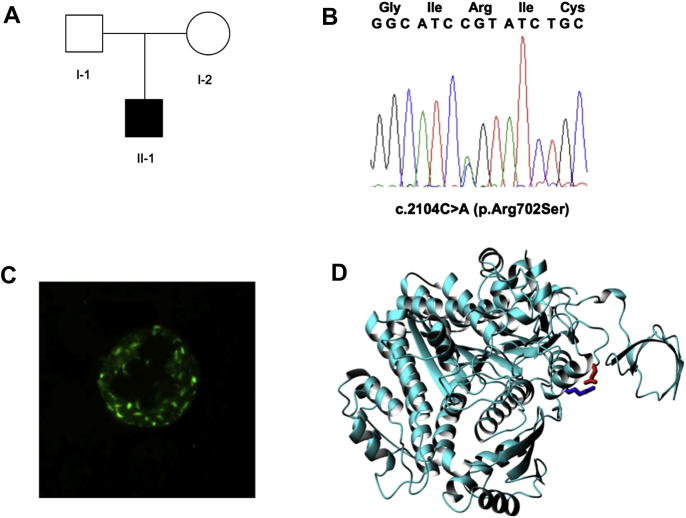

Fig. 2.

Identification of the p.Arg702Ser mutation in family 2. A) Family pedigree; B) Direct sequencing of PCR products of exon 16 with overlapping peaks of the heterozygous c.2104C > A mutation; C) Immunofluorescence analysis showing myosin-9 small aggregates in the patient neutrophils; D) Effect of the mutation on the structure (1br2). The ribbon representation is shown with the same orientation as before. The side chain of Arg702 is shown in blue, Glu94 is shown in red.

Family 3. The proband (I-2; Table 1) was a 33-year-old female referred for thrombocytopenia discovered for the first time at the age of 31 during her first pregnancy. Assessment of her medical history revealed easy bruising, menorrhagia, prolonged bleeding after minor wounds, and occasional epistaxis. The patient was also affected by type I von Willebrand disease which could contribute to bleeding tendency. She previously received a diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia and was treated with steroids and intravenous immunoglobulins without any responses. Assessment of family history revealed that her mother had a reduced platelet count diagnosed as immune thrombocytopenia; she received several courses of immunosuppressive treatments and splenectomy without any increases in platelet count, and she died because of severe bleeding. At our evaluation, platelet count was 85 × 109/L, as assessed by phase contrast microscopy. Examination of peripheral blood smears showed giant platelets and typical Döhle-like inclusion bodies. In vitro aggregation studies revealed a moderately reduced response to all tested agonists, including ADP, epinephrine, collagen and ristocetin. Flow cytometry showed that while glycoprotein IIb–IIIa expression was increased compared to control, levels of Ib-IX were moderately reduced. The proband's two-year-old son also had thrombocytopenia (96 × 109/L), giant platelets and Döhle-like inclusions. The search for kidney damage and hearing loss returned normal findings in both the proband and her son, while ophthalmologic evaluation was normal in the proband (her son had no ophthalmologic evaluation done so far).

Family 4. The proband (II-1; Table 1) was an 8-year-old girl referred for mild thrombocytopenia (platelet count 123 × 109/L) and increased bleeding after adenoidectomy. Medical history revealed recurrent episodes of epistaxis and excessive bleeding after the loss of one milk tooth. She underwent surgical correction of umbilical hernia without complications. Examination of blood smears revealed giant platelets and Döhle-like inclusion bodies. In vitro functional studies (Born's method) showed normal platelet aggregation after stimulation with collagen, ristocetin, and ADP. Flow cytometry demonstrated normal platelet expression of glycoproteins IIb–IIIa, Ib-alpha, and Ib-beta. The proband's 43-year-old father also had thrombocytopenia (platelet count 116 × 109/L) discovered for the first time at the age of 28 when he was diagnosed as having immune thrombocytopenia. He presented with easy bruising and mild gum bleeding. He also had giant platelets and Döhle-like bodies at evaluation of blood smears. Except for a mild, clinically unnoticed, bilateral hearing loss limited to the higher frequencies (30 dB at 8 kHz) in the proband's father, no extra-hematological manifestations of the MYH9-RD were observed in both the family members.

Family 5. The proband was a 20-year old female referred for a lifelong history of thrombocytopenia. She suffered from easy bruising and epistaxis. During infancy, she received a diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia and was treated with steroids without any response. At our evaluation, platelet count was 65 × 109/L, as assessed by phase contrast microscopy. Examination of her peripheral blood smears showed giant platelets and Döhle-like inclusions. Flow cytometry showed normal expression of the glycoproteins Ib–IX–V, IIb–IIIa, and Ia–IIa on the platelet surface. The search for kidney damage, hearing loss, and cataracts returned normal results.

2.2. Immunofluorescence studies

Immunofluorescence analysis for myosin-9 localization in neutrophils was performed on peripheral blood smears using the NMG2 mouse monoclonal antibody. Goat anti-mouse conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen, Milan, Italy) was used for secondary detection, as previously described [11].

2.3. Mutational analysis of MYH9

Probands of families 1 and 2 were screened for mutations in exons 1 and 16 of the MYH9 gene whereas probands of family 3, 4 and 5 were analyzed first for the “hot” exons 1, 16, 38 and 40 and then for the exons 10, 24, 25, 26, and 30. Proband of family 3 was also screened for the remaining MYH9 exons. The coding exons and the respective exon-intron boundaries of MYH9 were amplified by PCR and the products were sequenced using an ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit and an ABI 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described [11,12].

2.4. Bioinformatics

The structure with the closest sequence homology with MYH9 was identified by a Blast search of the PDB database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The query sequence was aligned to that of the template by the clustalx software. The model was built using the expasy Swiss-Model repository used in automated mode (http://swissmodel.expasy.org/repository/).

3. Results and discussion

In the probands, the diagnosis of MYH9-RD was suspected because of the finding of giant platelets and typical Döhle-like basophilic inclusions in neutrophils, which was associated with the extra-hematological manifestations of the disease in some cases (Table 1). In members of families 1–3 and 5, the immunofluorescence analysis revealed typical myosin-9 aggregates in neutrophil granulocytes, thus confirming the diagnosis [3,11]. In families 1 and 2, the staining pattern was characterized by numerous aggregates of small size (<0.5 μm) (Fig. 2C), suggesting a mutation affecting the motor domain of myosin-9 [2,4]. In families 3 and 5, patients' neutrophils had one to four large (2–5 μm) inclusions, often together with other small aggregates, as typically observed in subjects with alterations of the tail domain [2]. The immuofluorescence analysis was not performed in the members of family 4.

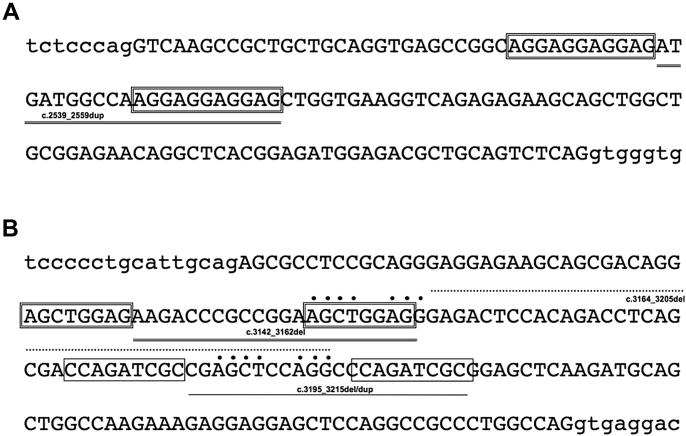

Mutational screening revealed five novel heterozygous mutations (Table 1). In the proband of families 1 and 2, we identified the c.101T > G (p.Val34Gly) and the c.2104C > A (p.Arg702Ser) missense mutations of exons 1 and 16, respectively (Figs. 1 and 2). In families 3 and 4 we detected two in frame alterations, the c.2539_2559dup (p.Met847_Glu853dup) in exon 20 and the c.3142_3162del (p.Lys1048_Glu1054del) in exon 24 (Fig. 3). In the last proband, the c.4338G > T mutation in exon 30 lead to the p.Asp1447Tyr substitution. Whereas the mutations in pedigrees 1, 3, and 4 segregated within the respective families, p.Arg702Ser identified in family 2 was likely to have occurred as de novo event, as the proband's parents did not present any feature of the disease. However, their DNA samples were not available to confirm this hypothesis. Familial history was not available for the proband of family 5. The five mutations were not reported in the SNP databases (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/SNP).

Fig. 3.

Schematic representation of the in-frame mutations identified in families 3 and 4. A) Nucleotide sequence of exon 20 (capital letters) and its flanking intronic regions where the c.2539_2559dup mutation is indicated. The repetitive AGGAGGAGGAG elements that are likely to be involved in the rearrangements are boxed. B) Nucleotide sequence of exon 24 (capital letter), where three deletions and one duplication (c.3142_3162del, c.3164_3205del, and c.3195_3215del/dup) so far identified are indicated. The repetitive that are elements to be likely involved in the rearrangements are boxed or dotted.

The amino acid alignment of the 13 human myosin heavy chains of class II showed conservation of valine 34 in all but one (MYH10) protein (Fig. 1C). Valine 34 is also conserved among the MYH9 orthologs (Canis lupus familiaris, Bos taurus, Mus musculus, Rattus norvegicus, Gallus gallus, and Danio rerio; at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene; data not shown), suggesting that it exerts a fundamental role in the structure and function of the class II myosins. In fact, inspection of the crystal structure (PDB entry name 1br2 for chicken smooth muscle myosin) shows that the mutation of valine 34 to a glycine affects an N-terminal residue of a small domain formed by two short beta-hairpins that pack against each other after relative rotation of an approximately 90° angle (Fig. 1D). The valine is in the interface and is buried from the solvent (exposed surface area of 1 Å2). It is surrounded by other hydrophobic residues (Ile49, Val57, Val59, Leu61, Leu70 and Ile75). The identified mutation is therefore likely to have a structural role and destabilize the protein fold.

The arginine at residue 702 is also a conserved amino acid, as previously reported for other two mutations hitting the same residue, p.Arg702Cys and p.Arg702His [2,7]. This residue is exposed on the protein surface (exposed surface area of 122 Å2). The side chain points towards the spatially nearby Glu94 with which Arg702 can form a salt bridge (Fig. 2D). Mutation of the residue in the shorter serine and cysteine or in the pH sensitive histidine could abolish this interaction and lead to destabilization of the structure. As arginine 702, even asparagine at residue 1447 of the coiled-coil tail is a conserved amino acid, which was previously found to be hit by mutations p.Asp1447His and p.Asp1447Val in a few MYH9-RD patients [11,13].

Regarding the two in frame mutations, it is interesting to note that other in frame alterations, two deletions (c.3164_3205del/p.Gly1055_Gln1068del and c.3195_3215del/p.Glu1066_Ala1072del) and one duplication (c.3195_3215dup/p.Glu1066_Ala1072dup) have previously been identified in exon 24 [14,15]. Such rearrangements are likely to derive from unequal homologous recombination between non-allelic regions repetitive elements, as hypothesized for c.3164_3205del and c.3195_3215del/dup. Indeed, exon 24 is rich of repetitive elements, including two AGCTGGAG units that are likely to be responsible for c.3142_3162del (Fig. 3A). Similarly, the duplicated stretch of 21 bp in exon 20 is flanked by the AGGAGGAGGAG repetitive sequence (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, all these rearrangements remove or add 7 or 14 residues of the α-coiled coil rod domain of the myosin, which consists of a 28 amino acid unit repeated 40 times [16]. This unit is subdivided itself in four heptad repeat motifs that are typical of the coiled-coil structure. More precisely, the p.Met847_Glu853dup and p.Lys1048_Glu1054 mutations hit the second and the eighth units and are likely to cause a significant dominant negative effect by interfering with the correct dimerization of myosin-9 and its assembly in filaments.

We and others have recently reported genotype–phenotype correlations in MYH9-RD [9,17]. Patients with mutations affecting the globular head domain of myosin-9 have lower platelet counts and higher prevalence and severity of extra-hematological manifestations than the subjects with mutations in the tail domain. Consistent with these studies, the patients from family 1 presented with moderate to severe thrombocytopenia associated with sensorineural hearing loss and/or bilateral cataracts in both the adult members. Similarly, the patient of family 2 presented with very low platelet count associated with early-onset, profound deafness and proteinuric nephropathy. In particular, these findings confirm the previous observation that the arginine 702 substitution invariably affects the hearing and kidney function since the juvenile age [8–10]. On the contrary, patients from families 3–5 had slight to moderate thrombocytopenia and no extra-hematological manifestations, with the exception of a very mild, clinically unnoticed sensorineural hearing defect in the adult member of family 4.

Despite the history of severe sensorineural deafness since the pediatric age, in the proband of family 2 the MYH9-RD was suspected only after the administration of several unnecessary treatments, including splenectomy, as a result of a wrong diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia. As mentioned above, the mutation in this family is likely to have occurred as a de novo event, as both the patient's parents were healthy and had normal platelet counts. The lack of a familial history could have contributed to the misdiagnosis. Also the proband of family 3 received a wrong diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenia and undue treatments, despite her mother had a history of thrombocytopenia unresponsive to immunosuppressive drugs and splenectomy. These case reports emphasize the importance of considering the associated clinical manifestations typical of syndromic inherited thrombocytopenias, as well as of the examination of blood smears to search for giant platelets and Döhle-like leukocyte inclusions, in the evaluation of patients with thrombocytopenia [18]. Moreover, although in many cases the genetic origin of thrombocytopenia can be easily suspected for the presence of a low platelet count in one of the parents, it appears important the awareness that about 35% of MYH9-RD patients are sporadic cases, and, therefore, present with no familial history of thrombocytopenia [2].

In conclusion, we reported five novel MYH9 mutations that extend the spectrum of alterations causing MYH9-RD. The phenotype of the reported patients is consistent with the current model of genotype–phenotype correlations.

Declaration of interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. This work was supported by grants from the Telethon Foundation (GGP06177), the Italian Ministry of Health (PRIN 2008), the Italian ISS (Istituto Superiore di Sanità), IRCCS Burlo Garofolo (Grant no. 34/07) and IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo Foundation.

References

- 1.Althaus K., Greinacher A. MYH9-related platelet disorders. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2009;35:189–203. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1220327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balduini C.L., Pecci A., Savoia A. Recent advances in the understanding and management of MYH9-related inherited thrombocytopenias. Br. J. Haematol. 2011;154:161–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunishima S., Matsushita T., Kojima T., Sako M., Kimura F., Jo E.K., Inoue C., Kamiya T., Saito H. Immunofluorescence analysis of neutrophil nonmuscle myosin heavy chain-A in MYH9 disorders: association of subcellular localization with MYH9 mutations. Lab. Invest. 2003;83:115–122. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000050960.48774.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kunishima S., Saito H. Advances in the understanding of MYH9 disorders. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2010;17:405–410. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32833c069c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pecci A., Granata A., Fiore C.E., Balduini C.L. Renin-angiotensin system blockade is effective in reducing proteinuria of patients with progressive nephropathy caused by MYH9 mutations (Fechtner–Epstein syndrome) Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2008;23:2690–2692. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley M.J., Jawien W., Ortel T.L., Korczak J.F. Mutation of MYH9, encoding non-muscle myosin heavy chain A, in May–Hegglin anomaly. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:106–108. doi: 10.1038/79069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The May–Hegglin/Fechtner syndrome consortium, mutations in MYH9 result in the May–Hegglin anomaly, and Fechtner and Sebastian syndromes. Nat. Genet. 2000;26:103–105. doi: 10.1038/79063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han K.H., Lee H., Kang H.G., Moon K.C., Lee J.H., Park Y.S., Ha I.S., Ahn H.S., Choi Y., Cheong H.I. Renal manifestations of patients with MYH9-related disorders. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2011;26:549–555. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1735-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pecci A., Panza E., Pujol-Moix N., Klersy C., Di Bari F., Bozzi V., Gresele P., Lethagen S., Fabris F., Dufour C., Granata A., Doubek M., Pecoraro C., Koivisto P.A., Heller P.G., Iolascon A., Alvisi P., Schwabe D., De Candia E., Rocca B., Russo U., Ramenghi U., Noris P., Seri M., Balduini C.L., Savoia A. Position of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA (NMMHC-IIA) mutations predicts the natural history of MYH9-related disease. Hum. Mutat. 2008;29:409–417. doi: 10.1002/humu.20661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sekine T., Konno M., Sasaki S., Moritani S., Miura T., Wong W.S., Nishio H., Nishiguchi T., Ohuchi M.Y., Tsuchiya S., Matsuyama T., Kanegane H., Ida K., Miura K., Harita Y., Hattori M., Horita S., Igarashi T., Saito H., Kunishima S. Patients with Epstein–Fechtner syndromes owing to MYH9 R702 mutations develop progressive proteinuric renal disease. Kidney Int. 2010;78:207–214. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Savoia A., De Rocco D., Panza E., Bozzi V., Scandellari R., Loffredo G., Mumford A., Heller P.G., Noris P., De Groot M.R., Giani M., Freddi P., Scognamiglio F., Riondino S., Pujol-Moix N., Fabris F., Seri M., Balduini C.L., Pecci A. Heavy chain myosin 9-related disease (MYH9-RD): neutrophil inclusions of myosin-9 as a pathognomonic sign of the disorder. Thromb. Haemost. 2010;103:826–832. doi: 10.1160/TH09-08-0593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Rocco D., Heller P.G., Girotto G., Pastore A., Glembotsky A.C., Marta R.F., Bozzi V., Pecci A., Molinas F.C., Savoia A. MYH9 related disease: a novel missense Ala95Asp mutation of the MYH9 gene. Platelets. 2009 doi: 10.3109/09537100903349620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burt R.A., Joseph J.E., Milliken S., Collinge J.E., Kile B.T. Description of a novel mutation leading to MYH9-related disease. Thromb. Res. 2008;122:861–863. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Rocco D., Pujol-Moix N., Pecci A., Faletra F., Bozzi V., Balduini C.L., Savoia A. Identification of the first duplication in MYH9-related disease: a hot spot for hot unequal crossing-over within exon 24 of the MYH9 gene. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 2009;52:191–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki K., Kunishima S., Fujii W., Higashihara M. Identification of three in-frame deletion mutations in MYH9 disorders suggesting an important hot spot for small rearrangements in MYH9 exon 24. Eur. J. Haematol. 2009;83:230–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blair E., Redwood C., de Jesus Oliveira M., Moolman-Smook J.C., Brink P., Corfield V.A., Ostman-Smith I., Watkins H. Mutations of the light meromyosin domain of the beta-myosin heavy chain rod in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2002;90:263–269. doi: 10.1161/hh0302.104532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong F., Li S., Pujol-Moix N., Luban N.L., Shin S.W., Seo J.H., Ruiz-Saez A., Demeter J., Langdon S., Kelley M.J. Genotype-phenotype correlation in MYH9-related thrombocytopenia. Br. J. Haematol. 2005;130:620–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Geddis A.E., Balduini C.L. Diagnosis of immune thrombocytopenic purpura in children. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2007;14:520–525. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e3282ab98f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]