SUMMARY

Extracranial meningiomas of the head and neck region are rare neoplasms, the majority being a secondary location of a primary intracranial tumour. We herewith report three rare cases of extracranial meningiomas, located in the temporal muscle, parotid gland and nasal cavity, together with complete pathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Prognosis of this tumour is generally excellent. Surgical excision is the treatment of choice, with no need for further treatment; nevertheless, differential diagnosis must consider other more common tumours of the head and neck and be based on histopathologic examination and relative techniques, including examination of frozen sections. This procedure is particularly useful assessing surgical treatment and should be performed whenever possible to exclude the malignant nature of the lesion and avoid over-treatment. All three patients underwent surgery and are alive and disease-free.

KEY WORDS: Extracranial meningioma, Head and neck, Parotid gland

RIASSUNTO

I meningiomi extracranici della regione testa-collo sono neoplasie rare, dal momento che la maggior parte di esse risulta essere una localizzazione secondaria di un tumore primitivo intracranico. Vengono di seguito descritti tre casi clinici di meningioma extracranico localizzati nel muscolo temporale, nella ghiandola parotide e nella cavità nasale. L'asportazione chirurgica è il trattamento di elezione e la prognosi di questo tipo di neoplasia è generalmente eccellente. Per la diagnosi differenziale istopatologica di queste neoplasie è necessario considerare i tumori più comuni della regione testa-collo. In particolare l'esame istopatologico perioperatorio è molto utile nell'indirizzare il trattamento chirurgico e dovrebbe essere sempre eseguito per escludere la natura maligna della lesione evitando un "over-treatment". I nostri pazienti sono stati sottoposti ad intervento chirurgico e sono attualmente in buono stato di salute dopo il trattamento.

Introduction

According to the World Health Organization, meningioma is a tumour arising from arachnoidal cells and, in the majority of cases, its behaviour is benign. It accounts for 24-30% of all intracranial tumours and has an incidence of 13/100,000 per year in Italy and 1.4-4.5/100,000 elsewhere 1.

Extracranial meningiomas are rare; the majority have a secondary location of a primary intracranial tumour. Therefore, once the diagnosis of meningioma is established, the presence of a meningioma of the neuraxis or extension of a primary central meningioma must be excluded.

We herein report three cases of extracranial meningioma, located in the temporal muscle, parotid gland and nasal cavity.

Case series

Case 1

A 38-year-old woman came to our observation with a 7 cm mass involving the temporal muscle. At frozen sections during surgery we observed an epithelioid proliferation invading the muscle, the temporal cortical and the zygomatic arch bone tissue. The final histopathological examination showed nodular aggregates of cells with regular nuclei.

Case 2

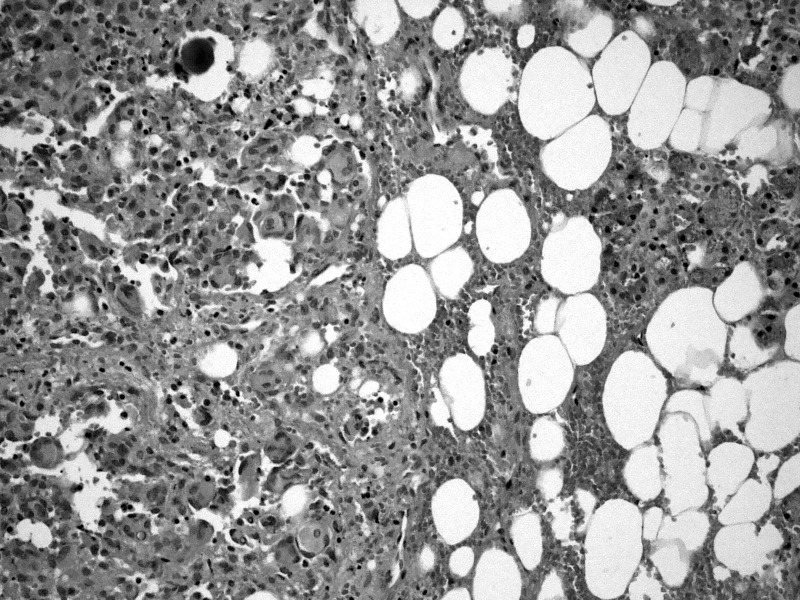

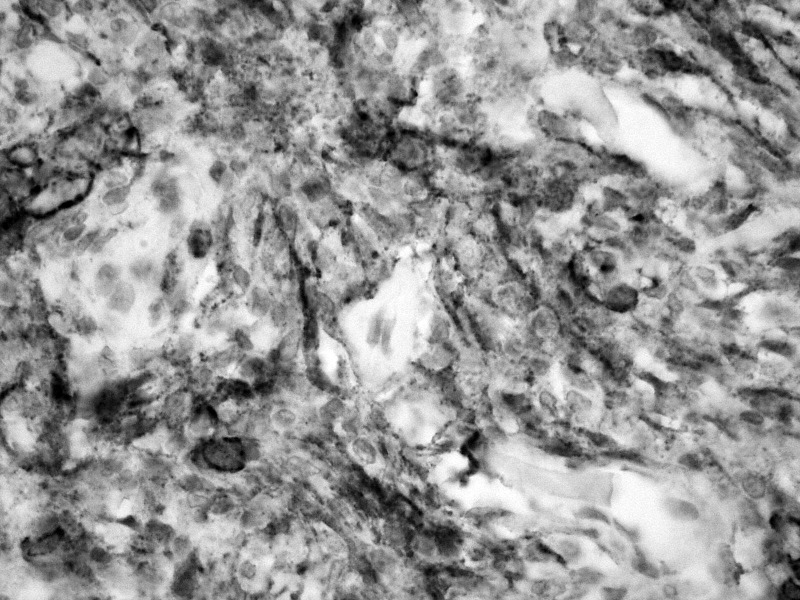

A 69-year-old woman came to our observation for trisma and dysphagia. NMRI revealed a neoplasm of the parapharyngeal space extending to the inferior parotid pole and dislocating the pterygoideus muscles. Frozen sections showed an epithelioid growth pattern of the mass, infiltrating the salivary gland and glossopharyngeal nerve. Final histopathological examination showed a neoplastic growth made of lobules of neoplastic cells and bound by fusocellular cells, with vortex and syncytial structures (Fig. 1). The ultrastructural report showed cells with complex interdigitating cytoplasmic processes joined by small desmosomes and abundant intracytoplasmic vimentin intermediate filaments (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Haematoxylin-eosin staining of the transitional cell meningioma with a psammoma body infiltrating the parotid gland (20×).

Fig. 2.

Long, slender cytoplasmic processes of neighbour cells (p); in the encircled areas two small desmosomes are visible; v: vimentine intermediate filaments.

Case 3

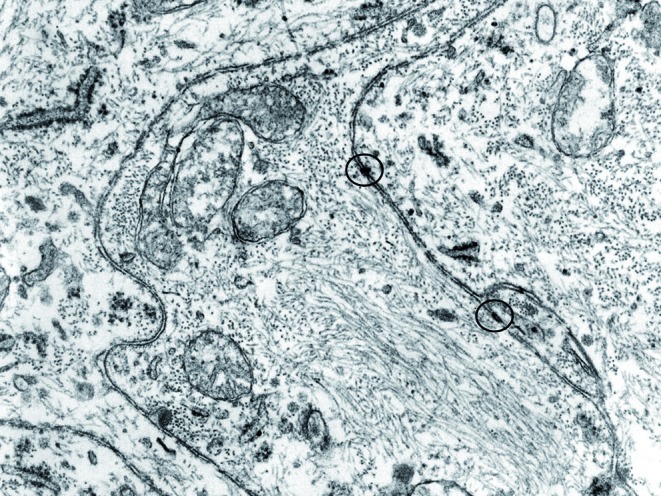

A 34-year-old woman came to our observation for a nasal mass resembling inverted papilloma. The patient underwent preoperative CT and MRI imaging (Fig. 3a-b); intraoperative frozen sections examination showed a well differentiated mesenchymal neoplasia. The final histopathological examination showed a fusocellular proliferation involving chorion, intermingled with fibrous areas and locally extending to trabecular bone tissue.

Fig. 3.

CT/MRI showing an oval mass occupying the left ethmoidal sinuses expanding into the nasal fossa, without infiltration of extranasal structures (a/b). MRI at 1 year after surgical removal of the mass (c).

All tumours were surgically removed, and all patients are alive and disease-free after surgery. Figure 3c shows the MRI follow-up of case 3 after one-year.

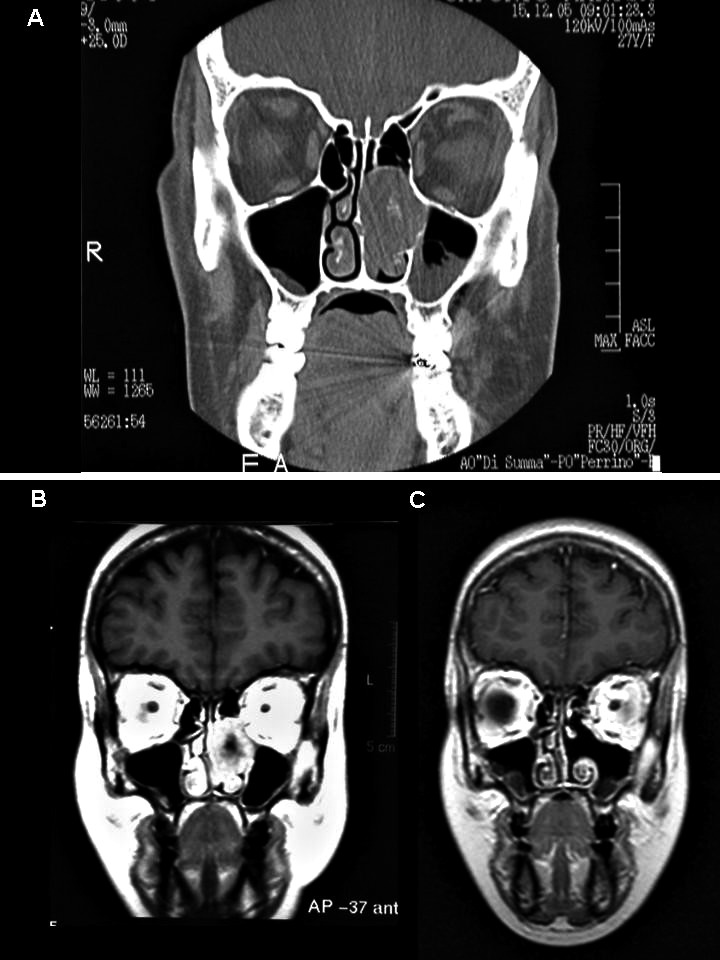

n all cases, immunohistochemistry was positive for epithelial membrane antigen (Fig. 4), weakly positive for S-100, negative for gliofibrillary protein, CD31, cytokeratin pool, CD34, smooth muscle actin, chromogranin A, synaptophysin and melanocytic antigen. Immunoreactive Ki-67 cells were less than 5%.

Fig. 4.

Fusocellular proliferation showing positivity for epithelial membrane antigen (40×).

Discussion

Primary extracranial meningiomas of head and neck region are rare tumours, the majority being a secondary location of a primary intracranial tumour, accounting for 1-2% of all meningiomas and with a generally favourable prognosis. Therefore, once the diagnosis of meningioma is established, the presence of a meningioma of the neuraxis or extension of a primary central meningioma should be excluded.

The most frequent extracranial sites reported are the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses 2, cranial bones 3, middle ear 4, scalp and soft tissues of the face and neck and parotid gland. The largest series of extracranial head and neck meningiomas encompass 146 cases 5, among which the majority was of the skin and scalp (n = 59), middle ear (n = 26), nasal cavity (n = 17), temporal bone (n = 2) and parotid gland (n = 1). Other large series consider the sinonasal tract (n = 30) 6, ear and temporal bone meningiomas 4. The aetiopathogenesis of extracranial meningiomas resides in the migration of arachnoid cells deriving from the neural crest, but different mechanisms have been proposed such as originating from arachnoid cells of nerve sheaths emerging from skull foramina, from Pacchionian bodies possibly displaced or entrapped in an extracranial location during embryologic development, by trauma or cerebral hypertension displacing arachnoid islets or deriving from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells 7.

In our cases, no primary cranial meningioma was documented by traditional radiological investigations. Extracranial meningiomas exhibit various different histologic patterns just as their intracranial counterparts 8. In our mini-series, two were transitional, and one meningotheliomatous.

By cytology, meningotheliomatous cells show bland nuclei with delicate chromatin and intranuclear pseudoinclusions. The immunohistochemical profile of extracranial meningiomas is indistinguishable from intracranial lesions. All tumours expressed epithelial membrane antigen and vimentin, variable expression of protein S-100 and were negative for acidic gliofibrillary protein.

Although the lesions had a radiographic and histological growth pattern that was aggressive, none were diagnosed as a malignant meningioma. Their indolent clinical behaviour was further suggested by cellular immunoreactivity for Ki-67, which was less than 5%. Differential diagnosis includes different benign and malignant tumours, such as epithelial neoplasms (carcinoma), tumours originating from the neural crest (melanoma, olfactory neuroblastoma) and vascular and mesenchymal tumours (angiofibroma, paraganglioma, ossifying fibroma) 8.

Histologic features and immunohistochemical findings can easily separate these entities, especially in the differential diagnosis between carcinoma and melanoma; in more intriguing cases immunohistochemistry for cytokeratins, S-100 protein and HM B-45 allows distinction from meningiomas. Prognosis of primary meningioma is generally excellent, thus supporting the indolent growth of meningiomas, except for rare malignant forms 9 10; surgical excision is the treatment of choice, with no need for further treatment. Recurrences usually develop in the same site as the primary lesion and probably represent residual disease rather than recurrent tumour. Metastatic disease was not present in our patients. Clinical and radiographic features of these tumours cannot predict the nature of these lesions. Therefore, histopathologic examination is necessary as it can distinguish these neoplasms from other head and neck tumours. In particular, frozen sections are particularly useful in assessing the surgical procedure and should be performed whenever possible to exclude the malignant nature of the lesion and avoid overtreatment. As for the clinical course, surgical excision was curative in these cases, in agreement with the lack of morphological features of aggressive behaviour. All our patients are alive and disease-free after surgery.

References

- 1.Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavanee WK, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2007. pp. 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrulionis M, Valeviciene N, Paulauskiene I, et al. Primary extracranial meningioma of the sinonasal tract. Acta Radiol. 2005;46:415–418. doi: 10.1080/02841850510021210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones AC, Freedman PD. Primary extracranial meningioma of the mandible: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001;91:338–341. doi: 10.1067/moe.2001.112947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson LD, Bouffard JP, Sandberg GD, et al. Primary Ear and temporal bone meningiomas: a clinicopathological study of 36 cases with a review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:236–245. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000056631.15739.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rushing EJ, Bouffard JP, McCall S, et al. Primary extracranial meningiomas: an analysis of 146 cases. Head Neck Pathol. 2009;3:116–130. doi: 10.1007/s12105-009-0118-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson LD, Gyure KA. Extracranial sinonasal tract meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:640–650. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200005000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Serry P, Rombaux PH, Ledeghen S, et al. Extracranial sinosal tract meningioma: a case report. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Bel. 2004;58:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burger PC, Scheithauer BW. Tumors of the central nervous system. 3rd series ed. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1994. Tumors of meningothelial cells; pp. 259–286. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dominguez-Malagon H, Ordonez NG. Malignant meningioma of the parapharyngeal space: a case report. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1996;20:55–59. doi: 10.3109/01913129609023238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huszar M, Fanburg JC, Richard Dickersin G, et al. Retroperitoneal malignant meningioma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:492–499. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199604000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]