Abstract

Background

In the present study we identified a novel gene, Homo Sapiens Chromosome 1 ORF109 (c1orf109, GenBank ID: NM_017850.1), which encodes a substrate of CK2. We analyzed the regulation mode of the gene, the expression pattern and subcellular localization of the predicted protein in the cell, and its role involving in cell proliferation and cell cycle control.

Methods

Dual-luciferase reporter assay, chromatin immunoprecipitation and EMSA were used to analysis the basal transcriptional requirements of the predicted promoter regions. C1ORF109 expression was assessed by western blot analysis. The subcellular localization of C1ORF109 was detected by immunofluorescence and immune colloidal gold technique. Cell proliferation was evaluated using MTT assay and colony-forming assay.

Results

We found that two cis-acting elements within the crucial region of the c1orf109 promoter, one TATA box and one CAAT box, are required for maximal transcription of the c1orf109 gene. The 5′ flanking region of the c1orf109 gene could bind specific transcription factors and Sp1 may be one of them. Employing western blot analysis, we detected upregulated expression of c1orf109 in multiple cancer cell lines. The protein C1ORF109 was mainly located in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Moreover, we also found that C1ORF109 was a phosphoprotein in vivo and could be phosphorylated by the protein kinase CK2 in vitro. Exogenous expression of C1ORF109 in breast cancer Hs578T cells induced an increase in colony number and cell proliferation. A concomitant rise in levels of PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) and cyclinD1 expression was observed. Meanwhile, knockdown of c1orf109 by siRNA in breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells confirmed the role of c1orf109 in proliferation.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings suggest that C1ORF109 may be the downstream target of protein kinase CK2 and involved in the regulation of cancer cell proliferation.

Keywords: Promoter, Transcription, CK2 kinase, c1orf109, Proliferation

Background

CK2 (formerly known as casein kinase II) is a ubiquitous, highly conserved and messenger-independent protein serine/threonine kinase composed of two catalytic α subunits (αα, αα′, or α′α′) and two regulatory β subunits in eukaryotic cells [1,2]. To date, more than 300 potential substrates located in various compartments of the cell have been identified [3]. A unique property of CK2 is that it can use both ATP and GTP as the phosphate donor. CK2 plays a global role in cell cycle progression, cell growth and proliferation, cell survival and cell death [4-8]. Lack of any on/off regulatory mechanism, CK2 is constitutively active in cells. It was postulated that the intracellular dynamic shuttling of CK2 might represent a general mechanism of its regulation [9]. Emerging evidence shows that CK2 signaling is dysregulated in many human diseases, including cancer. CK2 is upregulated in all cancers that have been examined [10-12]. Although the kinase has been studied for over 50 years, its physiological role and regulatory mechanism have not been thoroughly elucidated.

The identification of cancer associated molecular alterations has exploited many insights into the roles of oncogenes or tumor suppressor genes in cancer progression. Previously, we obtained an unknown cDNA fragment named OPB7-1, which had different expression levels in two human lung cancer cell lines with different metastasis potentials [13]. Next, we mapped it to human chromosome 1p34 by radiation hybridization mapping [14]. Bioinformatic methods, RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) and sequencing were performed to obtain the 3′ and 5′ ends of the gene from normal human lung tissue. BLASTN results revealed that this cDNA sequence was homologous with Homo Sapiens Chromosome 1 ORF109 (c1orf109, GenBank ID: NM_017850.1). The mRNA sequences of c1orf109 are divided into five exons by four introns. The hypothetical protein C1ORF109 consists of 203 amino acids, and the predicted molecular weight and pI are 23.4kD and 5.47 respectively. However, no functional study on c1orf109 has been reported.

In order to investigate the biological function of c1orf109 in the cell, we analyzed the putative promoter and the biological features using bioinformatic tools. Meanwhile, we identified the existence and subcellular location of endogenous C1ORF109 protein. In addition, we also investigated the role of c1orf109 gene involving in cancer cell proliferation.

Methods

Cell lines and reagents

HEK293, HeLa, MDA-MB-231 and Hs 578 T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cells were cultured in accordance with the recommendations of ATCC. Oligonucleotides were synthesized by Invitrogen. Anti-Flag M5 and anti-C1ORF109 antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-phosphoserine antibodies were from BD. Anti-PCNA and anti-cylcinD1 antibodies were from Abcam plc.

Generation of c1orf109 promoter-luciferase constructs

PCR amplification was performed with c1orf109-specific primers to clone the putative c1orf109 5′ proximal promoter. An approximately 1.8 kb fragment that contained the immediate 5′-flanking sequence of the putative c1orf109 promoter (Genbank ID: AC104336) was amplified. This 1.8 kb fragment was subcloned into the pGL3-basic vector (Promega). The complete sequence was identified with sequencing by the 3130 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). Progressive 5′ deletions and site-directed mutations of putative cis-elements were achieved by PCR with the primers listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotides used in promoter cloning and site-directed mutagenesis

| Oligonucleotide | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| PR |

CGAGATCTCGTGCCTGGCTACTGAGTCGC |

promoter cloning |

| PF-1795 |

CGACGCGTCGAGTTGTGGTCCAGGCTTGTTTCCC |

promoter cloning |

| PF-428 |

CGACGCGTCGTTCCAGCCTCTCGGTTTCAGGG |

promoter cloning |

| PF-216 |

CGACGCGTCGCTAACAGGACATGCCACCAC |

promoter cloning |

| PF-177 |

CGACGCGTCGCCGCAGGCTGACAAATGAGAAG |

promoter cloning |

| PF-93 |

CGACGCGTCGCCACATGTTGGACTACAGTAC |

promoter cloning |

| CAAT I mutR |

TGGGACTGGATGTTGGGACCG |

mutagenesis |

| CAAT II mutR |

TTAAACTGGGTGGCGGTGGTG |

mutagenesis |

| CAAT III mutR |

GACACTGTGTATCACAACCAACTGGC |

mutagenesis |

| TATA mutR |

CGAGATCTCTGCCTGGCTACTGAGTCGCGAAAATCTCTCGTAGTG |

mutagenesis |

| ChIP1F |

AGAGCGGCTCTACAGTCAAC |

ChIP |

| ChIP1R |

TATTGCAGAGCCGCCACAAGGC |

ChIP |

| ChIP2F |

GAATGATAGAGGAGCAGG |

ChIP |

| ChIP2R |

ATCCTCAGGCACCCAGCAGAC |

ChIP |

| ChIP3F |

TTCCAGCCTCTCGGTTTCAGGG |

ChIP |

| ChIP3R |

CTGCCTGGCTACTGAGTCGCGA |

ChIP |

| ChIP InpF |

GGGTTCTCACGCTTTGGCTGTC |

ChIP |

| ChIP InpR |

CCGCTCTTTTAAATCTGGGA |

ChIP |

| GC box | ACCCGGCTCCGCCCTGGCCGGCT | EMSA |

Note: The underlined letters indicate mutated nucleotides.

Transient transfection and dual-luciferase assay

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with various c1orf109 promoter-luciferase constructs by Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen). About 2 × 105 HEK293 cells in each well of a 24-well plate were transfected with 1.0 μg of each pGL3-c1orf109 promoter construct plus 50 ng of the phRL-SV40 vector. The firefly luciferase activity was examined 24 hr after transfection using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Renilla luciferase activity was used as an internal control. Each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSA was performed using Chemiluminescent EMSA Kit (Beyotime). Briefly, 5 μg of nuclear extract was incubated with 10 ng of each biotin-labeled probe in binding buffer for 30 min at room temperature. Meanwhile, reactions contained a 100-fold excess of the same unlabeled probe, and other unrelated probes were used to determine specific and nonspecific binding. Furthermore, specific antibodies against Sp1 for supershift assay were performed in other reactions. Then the reaction mixtures were separated in a 4 % nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel in 0.5 × TBE at 60 V for 2 hours. Then the DNA/protein complex was transferred to nylon membrane, conjugated with Streptavidin-HRP, visualized with ECL, and detected by the Odyssey Fc Imaging System. The probes used for EMSA are listed in Table I.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were performed as described previously [15] with slight modification. About 1 × 107 cells were fixed with 0.8 % formaldehyde for 10 min, lysed in 150 μl Buffer A (10 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM NaCl, 0.2 % NP40) for 10 min on ice. Spin down the precipitation and resuspend in 1 ml Buffer B (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA, 1 % SDS). The lysate was fragmented by sonication to yield fragments between 200 bp and 1000 bp, and then centrifuged at 13,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was whole cell extract (WCE). Three μg of anti-Sp1 antibody was added into tubes containing 200 μl WCE plus 300 μl Buffer C (16.7 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0, 167 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM EDTA, 0.01 % SDS, 1.1 % Triton X-100). After incubation, the antibody complexes were collected with protein A agarose beads and subjected to serial washes. Cross-linked chromatin was reversed at 65°C in the presence of 200 mM NaCl for 5 hr. The DNA fragments were then purified using chloroform-isoamyl alcohol. The PCR primers used to amplify the endogenous c1orf109 promoter were listed in Table 1. PCR products were then run on an agarose gel and photographed. Meanwhile, DNA fragment extracted from 200 μl WCE was saved as positive control. Another pair of primers (ChIP InpF/R) that amplified DNA sequences from ~60 bp to ~900 bp downstream of the the transcriptional start site (TSS) was used as negative control.

Phosphorylation by CK2 in vitro

The phosphorylation of the recombinant full-length C1ORF109 protein by CK2 in vitro was detected using the Casein Kinase 2 Assay Kit (Upstate). This assay is based on phosphorylation of a CK2 substrate using the transfer of the γ-phosphate of [γ-32P]-ATP by CK2 kinase. The phosphorylated substrate was separated from the residual [γ-32P]-ATP using P81 phosphocellulose paper, and [32P] incorporation into the substrate was measured using a scintillation counter and expressed as the calculated pmol phosphate incorporated into CK2 substrate peptide/min/ng of CK2.

To further verify C1ORF109 phosphorylation by CK2, about 0.1 μg of recombinant full-length C1ORF109 protein was incubated with human CK2 (Upstate) in Hybrid Buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT) and 0.1 mM ATP plus 4 μCi [γ-32P]-ATP (3000 Ci/mM) for 30 min at 25°C [16], and fractionated by SDS-PAGE. Dried Coomassie blue-stained gels were analyzed by the Storage Phosphor System (Cyclone).

siRNA and c1orf109 stably expressing cells

siRNA oligonucleotides were synthesized, and the sequences of the siRNA for human c1orf109 was 5′-UGGAAUGGUUGCAGGAUAUTT3′. A non-targeting siRNA, 5′-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3′, was used as a negative control. MDA-MB-231 cells were transfected with siRNA oligonucleotides using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen). Wild type c1orf109 was cloned into the pcDNA3.1-Flag vector. Hs578T cells were stably transfected with pcDNA3.1 or c1orf109 using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent followed by G418 (Merck) selection.

Cell proliferation assay

Proliferation was analyzed using MTT assay and colony-forming assay. In the MTT assay, 3 × 103 cells were plated in 100 μl media per well in 96-well dishes, the medium was removed and replaced with 100 μl fresh culture medium containing 1.2 mM MTT at the indicated time points. The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 4 hr. Next, 100 μl of SDS-HCl solution (10 % SDS, 0.01 M HCl) was added to each well. After incubation at 37°C for 4 hr, each sample was mixed using a pipette, and absorbance was read at 570 nm. In the colony-forming assay, cells were plated in 6-well dishes at 500 cells/well. Every 4 days, the medium was replaced with fresh medium. When the colonies were clearly visible (after about two weeks), they were stained with crystal violet and counted.

Immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 % NP-40, 0.1 % SDS, and 0.5 % sodium deoxycholate) containing 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mM PMSF. Equal amounts of cell lysates were electrophoresed in 12 % SDS-polyacrylamide gels, and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5 % defatted milk and probed with the indicated primary antibodies, and were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The ECL western blotting analysis system was used to detect the substrates.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were harvested and fixed in 70 % ice-cold ethanol for 10 minutes and incubated with RNase A (100 μg/ml) and propidium iodide (50 μg/ml) for 30 minutes, and 1 × 104 cells from each sample were subjected to fluorescence-activated cell sorter scan (Becton Dickinson) analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the two-tailed Student’s t test and one-way ANOVA where appropriate. The data were presented as means ± S.D. obtained from three independent experiments. Results were considered to be statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results and discussion

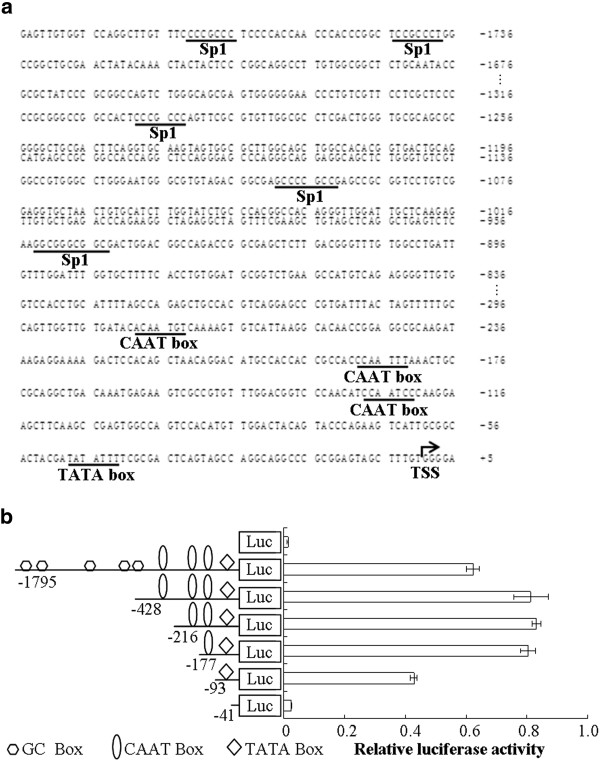

Identification of cis-acting elements in the c1orf109 promoter region

Because c1orf109 is a novel gene, its mechanism of regulation is unclear. To analyze the putative promoter of the human c1orf109 gene, an approximately 1.8 kb DNA sequence located upstream of the TSS was cloned as described in the Methods and Materials section. Nucleotide sequence analysis of the 5′ flanking region of the c1orf109 gene using MatInspector online software revealed the presence of one TATA box (at −48 bp) and three CAAT boxes (at −135 bp, -200 bp, -293 bp respectively), as shown in Figure 1A. Progressive 5′ deletions of the c1orf109 gene promoter constructs were generated to identify transcriptional regulatory elements (Figure 1B). All truncated constructs were transiently transfected into HEK293 cells. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized by co-transfection with a Renilla luciferase vector. Meanwhile, the promoter-less pGL3-basic vector was used as a negative control. Significant luciferase activity was observed after transfection of the construct containing the proximal 93 bp region upstream of the TSS. Transfection of sequences further upstream, from −177 to −428 bp, resulted in a significant increase in promoter activity, whereas transfection of the proximal 41 bp did not generate luciferase activity. The results indicate that the region from −41 to −177 bp contains positive regulatory elements essential for achieving maximal c1orf109 promoter activity.

Figure 1.

Identification of essentialcis-actingelements within thec1orf109promoter.(A) DNA sequence analysis of the 5′ flanking region of human c1orf109 gene. The nucleotide sequence is numbered with the transcriptional start site (TSS) as +1 (dark arrow). MatInspector online software was used to predict the putative transcription factor binding sites, which are underlined and indicated by name. (B) Deletion analysis of the c1orf109 promoter. The truncated promoter fragments were inserted into the luciferase reporter vector pGL3-basic (Luc). Approximately 2 × 105 HEK293 in each well of 24-well plate were transfected with 1.0 μg each of pGL3-c1orf109 promoter constructs plus 50 ng of phRL-SV40 vector. The firefly luciferase activity was assayed 24 hr after transfection and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. Values are represented by means ± S.D. obtained from three independent experiments. Deletion from −177 to −101 bp and −101 to −41 bp led to extreme reduction of activity. The region within −177 bp of the c1orf109 promoter contains multiple potentially important transcription factor binding sites including CAAT and TATA boxes.

To further identify the functional significance of the potential transcription factor binding sites within the region of −41 to −177 bp, including the putative CAAT boxes and TATA box, serial site-directed mutation constructs were used to analyze their effects on luciferase activity in HEK293 cells. Disruption of the CAAT I and TATA box sites caused impaired promoter activity by approximately 44 to 47 percent. In contrast, mutations of the CAAT box II or CAAT box III sites did not affect c1orf109 promoter activity (Figure 2). Therefore, we conclude that CAAT box I and TATA box act as important cis-acting elements within the c1orf109 promoter.

Figure 2.

Effects of site-directed mutations on thec1orf109promoter activity. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with the −428 bp region of c1orf109 promoter constructs with different mutations of CAAT or TATA box sites. The firefly luciferase activity was assayed 24 hr after transfection and normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. Values represent the means ± S.D. of three independent experiments. * P < 0.05 versus the wild type control.

Participation of Sp1 in c1orf109 transcription

Sp1 is a transcription factor that either enhances or represses the activity of promoters of genes involved in differentiation, cell cycle progression, and oncogenesis [17]. The presence of several potential GC boxes suggested that transcriptional factor Sp1 may be involved in the transcriptional regulation of c1orf109 gene. To confirm whether Sp1 directly interact with c1orf109 promoter, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay was performed. HeLa cells were fixed, lysed and fragmented as described in methods and materials. DNA was optimally sheared with a distribution of fragments from 200 to1000 bp, as shown in Figure 3A. Immunoprecipitation of DNA/protein complexes using antibodies against Sp1 was followed by PCR amplification. As shown in Figure 3B, anti-Sp1 antibody was capable of immunoprecipitating the c1orf109 promoter fragment containing the GC box 4 (Figure 3B, lane 9); however, primers ChIP InpF/R failed to produce a PCR product (Figure 3B, lanes 4, 8 and 12), indicating that Sp1 directly interacted with c1orf109 promoter region.

Figure 3.

Characterization of the transcription factors responsible for Sp1 binding sites in thec1orf109gene promoter.(A) Distribution of DNA fragments by sonication. DNA fragments were sheared with a distribution of fragments from 200 to1000 bp. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay using HeLa cell lysates. Chromatin was immunoprecipitated using antibody against Sp1. Lanes 1, 5 and 9 were PCR products from immunoprecipitation using primers ChIP 1 F/R, ChIP 2 F/R and ChIP 3 F/R respectively. Lanes 2, 6 and 10 were PCR products from WCE using primers ChIP 1 F/R, ChIP 2 F/R and ChIP 3 F/R respectively. Lane 3, 7 and 11 were PCR products using ChIP InpF/R from WCE. Lanes 4, 8 and 12 were PCR products using ChIP InpF/R from immunoprecipitation. WCE, whole cell extract. (C) Biotin labeled oligonucleotides corresponding to GC boxes were used in an EMSA with nuclear proteins from HeLa cells. Specific shift-bands are indicated with closed arrowheads. NE, nuclear extract; SC, 100× specific competitors; NSC, 100× nonspecific competitors.

To detect whether Sp1 interacts directly with the potential GC boxes, an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) was performed. Oligonucleotides corresponding to the binding sites for Sp1 in the c1orf109 promoter were designed (Table I). According to the results of EMSA (Figure 3C), the mobility of labeled probes corresponding to GC box 4 was shifted in the presence of nuclear protein prepared from HeLa cells. The binding specificity of each probe was verified by supershift when we added anti-Sp1 anitibody or excessive unlabeled oligonucleotide competitors. These data suggest that the CAAT box and TATA box are required for achieving the basal transcription of the c1orf109 gene. The 5′ flanking region of the c1orf109 gene could bind specific transcription factors and Sp1 may participate in the regulation of transcriptional expression of the gene. The activation of transcription by CAAT box and TATA box may be further modulated by GC box.

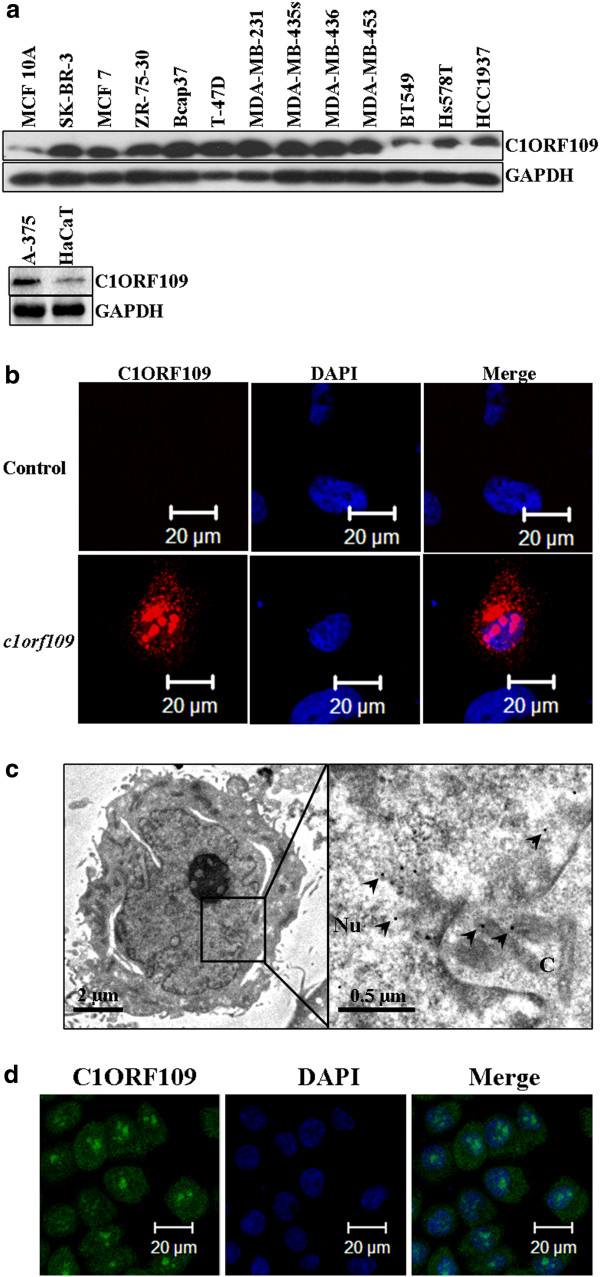

Upregulation of C1ORF109 in multiple cancer cell lines

Previously, we have reported that c1orf109 exhibited an increased expression in lung cancer tissues compared to paired adjacent non-tumor tissues using in situ hybridization with specific RNA probes [14]. To further identify the existence and expression pattern of the putative protein C1ORF109 in the cell, the expression of c1orf109 in 11 breast cancer cell lines and a melanoma cell line were detected by immunoblotting. Meanwhile, a non-tumorigenic epithelial cell line (MCF10A) [18] and an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT) [19] were used as control. As shown in Figure 4A, C1ORF109 levels were upregulated in tumorigenic cell lines compared to the control, especially in the cell lines derived from metastatic sites, such as the cell lines derived from pleural effusion (MDA-MB-436, MDA-MB-453, MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-435 s, T-47D, and SK-BR-3), and ascites (ZR-75-30). Furthermore, we also found that C1ORF109 was overexpressed in hepatocellular cancer tissues compared to paired adjacent non-tumorous tissues by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) (see Additional file 1). These findings indicate that increased expression of C1ORF109 may be involved in cancer progression.

Figure 4.

C1ORF109 is upregulated in multiple cancer cells and located in both the nucleus and cytoplasm.(A) C1ORF109 expression in 11 human breast cancer cell lines and one melanoma cell lines were detected by western blot analysis. The non-tumorigenic epithelial cell line MCF 10A and an immortalized human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT were used as control. (B) Immunofluorescence analysis showed the subcellular localization of C1ORF109 using an anti-Flag tag antibody. (C) Immunoelectron microscope with colloidal gold showed the subcellular localization of C1ORF109 using an anti-V5 epitope antibody. Arrows indicate the specific binding of gold particles. Nu, nucleus. C, cytoplasm. (D) The subcellular localization of endogenous C1ORF109 was detected in HeLa cells using anti-C1ORF109 antibody.

Subcellular localization of C1ORF109

The subcellular localization of the C1ORF109 protein was also examined using immunofluorescence. cDNA was subcloned into a pCMV-Flag vector. Hs578T cells were cultured on a round coverslip and transiently transfected with pCMV-Flag-c1orf109. A mock vector was used as negative control. The cells were subsequently fixed, incubated with TRITC-labeled antibodies, and analyzed by confocal microscopy. Positive signals were found mainly in the nucleus and cytoplasm. No signal was detected in the control cells (Figure 4B). To confirm further the subcellular localization of C1ORF109, an immune colloidal gold assay was performed in NIH3T3 cells that stably expressed V5 tagged C1ORF109. The samples were analyzed by transmission electron microscope, and the results showed that the colloidal gold particles (diameter, ~15 nm) mainly localized to the nucleus and cytoplasm (Figure 2C). In addition, the subcellular localization of endogenous C1ORF109 was detected in HeLa cells using anti-C1ORF109 antibodies (Figure 2D). These data indicate that C1ORF109 protein is mainly located in the nucleus and cytoplasm.

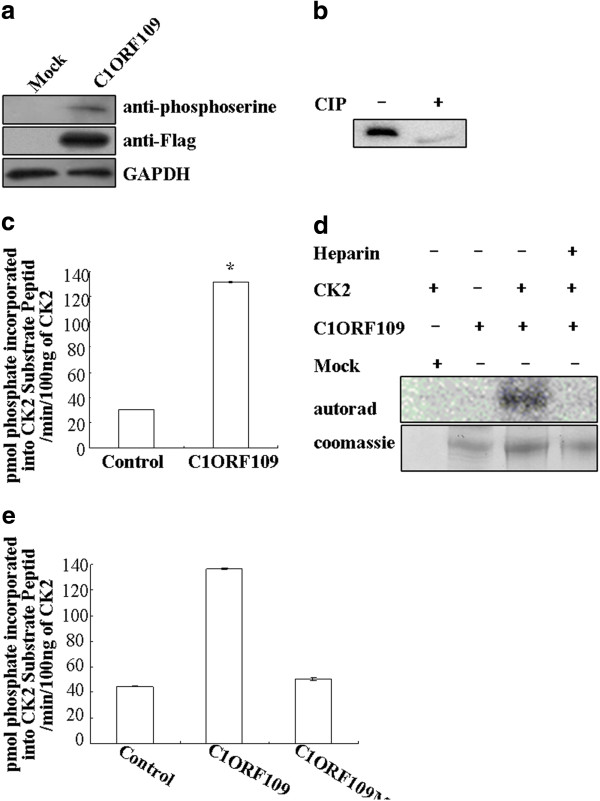

Phosphorylation of C1ORF109 by CK2 in vitro

Since c1orf109 has been shown to be involved in cancer progression, we focused on the biological functions of c1orf109 in the cell. To determine the functional domain of C1ORF109 at the molecular level, the PROSITE method was used to analyze the amino acid sequence, and three potential CK2 phosphorylation sites at serines 104, 134 and 182 were found. Therefore, C1ORF109 is predicted to be a phosphoprotein. The full-length C1ORF109 purified from HEK293 cells was recognized by anti-phosphoserine antibodies (Figure 5A). Moreover, treatment of C1ORF109 immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) resulted in different electrophoretic mobility compared with untreated C1ORF109 (Figure 5B). Together, these data imply that C1ORF109 is a phosphoprotein in eukaryotic cells.

Figure 5.

CK2 phosphorylates C1ORF109in vitro.(A) C1ORF109-Flag was immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells and was immunoblotted for anti-phosphoserine. (B) C1ORF109-Flag purified from HEK293 cells was treated or mock treated with calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) and immunoblotted for C1ORF109. (C) C1ORF109-Flag immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells was incubated with human CK2, and [γ-32P]-ATP, and the CPM was read in a scintillation counter subsequently. (D) C1ORF109-Flag purified from HEK293 cells was phosphorylated with human CK2 and [γ-32P]-ATP, fractionated by SDS-PAGE, and dried Coomassie blue-stained gels were examined by autoradiography. Heparin was used at 10 μg/ml. (E) Wild type C1ORF109 and C1ORF109Mut immunoprecipitated from HEK293 cells were incubated with human CK2, and [γ-32P]-ATP respectively, and the CPM was read in a scintillation counter subsequently.

To test whether C1ORF109 is a substrate of protein kinase CK2, the full-length C1ORF109 purified from HEK293 cells was incubated with human CK2, [γ-32P]-ATP in vitro, and the CPM was subsequently read in a scintillation counter. To exclude the influence of PKA, a PKA inhibitor cocktail was added to the reaction system. The results indicate that C1ORF109 is efficiently phosphorylated by CK2 in vitro (Figure 5C). Meanwhile, C1ORF109 phosphorylation was abolished by heparin, which is a specific inhibitor of protein kinase CK2 (Figure 5D). Next, serines 104, 134 and 182 were converted into nonphosphorylatable alanine residues yielding a mutant C1ORF109. C1ORF109Mut cannot be phosphorylated by CK2 in vitro (Figure 5E). These findings suggest that C1ORF109 is specifically phosphorylated by CK2 in vitro, and that it is a substrate of the protein kinase CK2.

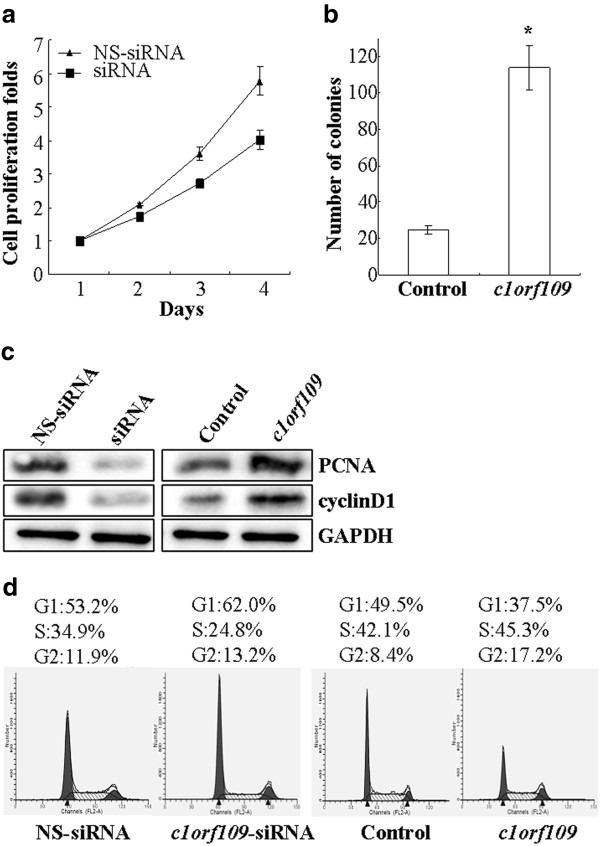

Involvement of C1ORF109 in cancer cell proliferation

CK2, a ubiquitous protein serine/threonine kinase with hundreds of substrates, is essential for the modulation of cell growth and proliferation. Since C1ORF109 has been identified to be a substrate of CK2, it might play a role in the modulation of cell proliferation. To verify this postulation, MDA-MB-231 cells, which express endogenous C1ORF109 at high levels, were transiently transfected with c1orf109-siRNA to knock down endogenous C1ORF109 and showed a reduction in cell viability (P < 0.05, Figure 6A). However, Hs578T cells, which express low levels of endogenous C1ORF109, were stably transfected to overexpress exogenous C1ORF109 and showed a 5-fold increase in colony number in colony-forming assays (P < 0.05, Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

c1orf109is involved in the regulation of cancer cell proliferation.(A) MDA-MB-231 cells were transiently transfected with c1orf109-siRNA and were subcultured for an additional 4 days. Cell proliferation was assessed by MTT assay. A non-targeting siRNA was used as a negative control. (B) Hs578T cells were stably transfected with pcDNA3.1/c1orf109 construct. Cell proliferation was assessed by colony forming assay, as described in the Methods section. A mock plasmid was used as a control. (C) The expression levels of PCNA and cyclinD1 were detected by western blotting. (D) Cell cycle was assessed by PI staining.

The D-type cyclins (Dl, D2 and D3) are key governors of the progression from G1 to S phase of the mammalian cell cycle. These three D-type cyclins are expressed in overlapping and apparently redundant fashion in proliferating tissues [20,21]. PCNA, a regulator of DNA replication and cell cycle control, is a well-defined cell proliferation parameter [22,23]. We tested the effect of C1ORF109 overexpression or depletion on the expression levels of PCNA and cyclinD1. Downregulation of PCNA and cyclinD1 were detected in C1ORF109-depleted cells. Meanwhile, Hs578T cells stably expressing exogenous C1ORF109 showed increased expression of PCNA and cyclinD1 (Figure 6C). In addition, the effect of c1orf109 on cell cycle distribution was examined by flow cytometry. Cell cycle analysis of MDA-MB-231 cells transfected with c1orf109-siRNA showed an increase in G1 phase and a reduction in DNA synthetic activity (S phase), whereas stably expressing exogenous C1ORF109 in Hs578T cells resulted in fewer cells accumulating in G1 phase compared to the control (Figure6D). These results indicate that upregulation of c1orf109 in breast cancer cells could promote cancer cell proliferation in vitro, which is mainly due to the acceleration of G1 to S phase transition.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our experiments show that the unknown gene c1orf109 encodes a CK2 substrate and is involved in the modulation of cell proliferation. More work will be required to identify the molecular mechanisms by which CK2 regulates the expression of C1ORF109 and then affects cell proliferation.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

SSL and YL designed the study and drafted the manuscript. SSL performed the transcriptional analyses, qRT-PCR, MTT assay and colony forming assay. HXZ, HDJ and JH carried out the immunofluorescence and immunoelectron microscopy with colloidal gold. YPQ, LY and YZ helped to collect the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The expression of c1orf109 mRNA in hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) detected by quantitative real-time PCR.

Contributor Information

Shan-shan Liu, Email: liushanshan636@126.com.

Hong-xia Zheng, Email: zjin_mei@163.com.

Hua-dong Jiang, Email: jhd_1987@163.com.

Jie He, Email: joy_hejie@126.com.

Yang Yu, Email: fansyu@163.com.

You-peng Qu, Email: qyp1000@163.com.

Lei Yue, Email: smiley1001@163.com.

Yao Zhang, Email: zhangyao83326@163.com.

Yu Li, Email: liyugene@hit.edu.cn.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ji-lai Liu, Jie Su, and Zhu Wang for generating c1orf109 promoter-luciferase constructs. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.30170516 and No.30871271).

References

- Litchfield DW. Protein kinase CK2: structure, regulation and role in cellular decisions of life and death. Biochem J. 2003;369:1–15. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinna LA. Protein kinase CK2: a challenge to canons. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:3873–3878. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggio F, Pinna LA. One-thousand-and-one substrates of protein kinase CK2? FASEB J. 2003;17:349–368. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0473rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrin F, Chambaz EM, Bianchini L. A role for protein kinase CK2 in cell proliferation: evidence using a kinase-inactive mutant of CK2 catalytic subunit alpha. Oncogene. 2001;20:2010–2022. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad KA, Wang G, Unger G, Slaton J, Ahmed K. Protein kinase CK2–a key suppressor of apoptosis. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2008;48:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed K, Gerber DA, Cochet C. Joining the cell survival squad: an emerging role for protein kinase CK2. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12:226–230. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(02)02279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Ahmad KA, Ahmed K. Impact of protein kinase CK2 on inhibitor of apoptosis proteins (IAPs) in prostate cancer cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2008;316:91–97. doi: 10.1007/s11010-008-9810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St-Denis NA, Litchfield DW. Protein kinase CK2 in health and disease: From birth to death: the role of protein kinase CK2 in the regulation of cell proliferation and survival. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1817–1829. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-9150-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust M, Montenarh M. Subcellular localization of protein kinase CK2 – A key to its function? Cell & Tissue Res. 2000;301:329–340. doi: 10.1007/s004410000256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra B, Issinger OG. Protein kinase CK2 in human disease. Curr Medicinal Chem. 2008;15:1870–1886. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawfic S, Yu S, Wang H, Faust R, Davis A, Ahmed K. Protein kinase CK2 signal in neoplasia. Histol Histopathol. 2001;16:573–582. doi: 10.14670/HH-16.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trembley JH, Wang G, Unger G, Slaton J, Ahmed K. CK2: A key player in cancer biology. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1858–1867. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-9154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng XW, Li Y, Zhang GY, Wang RW, Li P. Molecular cloning of tumor metastasis related genes from human lung adenocarcinoma cells by mRNA differential display. Chinese J Med Genet. 1997;14:129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Fan H, Li Y, Deng YQ, Chen YZ, Feng HC, Fu SB, Zhang GY, Li P. Cloning and mapping analysis of cDNA fragment OPB7-1 gene in human lung adenocarcinoma. Chinese J Med Genet. 2003;20:156–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XH, Liu DP, Xin L. A simple chromatin immunoprecipitation assay protocol. Prog Biochem Biophys. 2003;30(4):634–638. [Google Scholar]

- Loizou JI, El-Khamisy SF, Zlatanou A, Moore DJ, Chan DW, Qin J, Sarno S, Meggio F, Pinna LA, Caldecott KW. The protein kinase CK2 facilitates repair of chromosomal DNA single-strand breaks. Cell. 2004;117:17–28. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Davie J. The role of Sp1 and Sp3 in normal and cancer cell biology. Ann Anat. 2010;192:275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soule H, McGrath CM. Immortal human mammary epithelial cell lines. US Patent 5,026,637 dated Jun 25 1991.

- Boukamp P, Petrussevska RT, Breitkreutz D, Hornung J, Markham A, Fusenig NE. Normal keratinization in a spontaneously immortalized aneuploid human keratinocyte cell line. J Cell Biol. 1988;106(3):761–771. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. D-type cyclins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:187–190. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(00)89005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. Cancer cell cycles. Science. 1996;274:1672–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga G, Hubscher U. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a dancer with many partners. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3051–3060. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strzalka W, Ziemienowicz A. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA): a key factor in DNA replication and cell cycle regulation. Ann Bot. 2011;107:1127–1140. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The expression of c1orf109 mRNA in hepatocellular carcinomas (HCCs) detected by quantitative real-time PCR.