Abstract

Background

Criteria for resectability of colon cancer liver metastases (CLM) are evolving, yet little is known about how physicians choose a therapeutic strategy for potentially resectable CLM.

Methods

Physicians completed a national Web-based survey that consisted of varied CLM conjoint tasks. Respondents chose among three treatment strategies: immediate liver resection (LR), preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery (C → LR), or palliative chemotherapy (PC). Data were analyzed by multinomial logistic regression, yielding odds ratios (OR).

Results

Of 219 respondents, 79 % practiced at academic centers and 63 % were in practice ≥10 years. Median number of cases evaluated was four per month. Surgical training varied: 51 % surgical oncology, 44 % hepato-pancreato-biliary/transplantation, 5 % no fellowship. Although each factor affected the choice of CLM therapy, the relative effect differed. Hilar lymph node disease predicted a strong aversion to LR with surgeons more likely to choose C → LR (OR 8.92) or PC (OR 49.9). Solitary lung metastasis also deterred choice of LR, with respondents favoring C → LR (OR 4.43) or PC (OR 6.97). After controlling for clinical factors, surgeons with more years in practice were more likely to choose PC over C → LR (OR 1.94) (P = 0.005). Surgical oncology-trained surgeons were more likely than hepatobiliary/transplant-trained surgeons to choose C → LR (OR 2.53) or PC (OR 4.15) (P <0.001).

Conclusions

This is the first nationwide study to define the relative impact of key clinical factors on choice of therapy for CLM. Although clinical factors influence choice of therapy, surgical subspeciality and physician experience are also important determinants of care.

Given that surgical resection remains the best chance for cure, there has been considerable interest in expanding the criteria for resectability of colorectal liver metastases.1–3 As the options for management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer continue to expand and become more complex, it remains unclear whether patients are being appropriately referred for optimal therapy. One small study noted that referral patterns of patients with liver metastasis remains low and is still based on traditional factors, rather than new multimodal criteria.4 Although highly specialized centers have published data on surgery for colorectal liver metastases in the setting of advanced patient age, extensive intrahepatic disease, or extrahepatic metastasis, the relative impact of these factors on the decision to offer surgical therapy has not been examined. Most studies on surgery for colorectal liver metastasis have focused on survival outcomes.5–8 There are minimal data on provider preferences or attitudes regarding the utilization and timing of hepatectomy in the setting of a modern paradigm of care, where patients may have a higher burden of disease both inside and outside the liver.9

Clinical judgment analyses can elicit the factors determining clinical decisions better than physician introspection alone.10,11 Conjoint analysis is a stated preference research method that uses stylized scenarios to elicit preferences that are valid predictors of real-world decisions.12,13 The relative influence of different factors on clinical decisions can be estimated by presenting respondents with a series of clinical vignettes incorporating multiple factors of interest.13 This method has been applied to clinical decision making in medicine on a limited basis. Our group has used this technique to elucidate the factors that drive surgical decision making in early hepatocellular carcinoma.13 In the present study, we sought to use conjoint analysis to understand how surgeons choose therapeutic strategies for potentially resectable colon cancer liver metastasis (CLM), including the interplay between patient-related and physician-related factors.

METHODS

Survey Instrument Design

Standard conjoint analysis methodology was used to design, implement, and analyze the survey.13 First, structured interviews were conducted with surgeons and medical oncologists who treat CLM in order to identify clinical factors influencing choice of therapy for CLM. These seven key clinical factors were then incorporated into 36 case scenarios (conjoint tasks) using an orthogonal array.14 In each case scenario, the respondent was asked which procedure he or she would recommend as initial therapy for colorectal liver metastasis: immediate liver resection (LR), preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery (C → LR), or palliative chemotherapy (PC) (Supplemental Fig. 1). A random subset of 10 case scenarios was chosen for each respondent.13

In addition to the case scenarios, the survey instrument included questions on practice characteristics and questions regarding attitudes toward surgical therapies for colorectal liver metastasis. General preferences for different therapeutic options were also assessed using a 1–5 Likert scale. The resulting survey instrument was then pilot tested and iteratively refined before invitation e-mails were sent to potential respondents. Invitations to take the survey were sent by e-mail to surgeons with an interest in liver surgery as identified by participation in one of several gastrointestinal cancer or liver surgery societies; e-mail addresses were obtained from publicly available sources such as Web sites and publications in the field.13,15

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were compared by Fisher’s exact test, the rank sum test, or the Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Choice data were analyzed by multinomial logistic regression models with robust variance estimates, yielding odds ratios (OR) that reflect the change in the odds of choosing a particular therapy over an alternative. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and statistical significance was established at P <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed by Stata/MP 10.1 for Windows (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The study protocol and survey instrument were approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine institutional review board.

RESULTS

A total of 1,032 e-mail invitations were sent to surgeons with an interest in liver surgery. The invitation was viewed by 466 surgeons and 219 eligible, complete responses were received (response rate 47 %). Practice characteristics of the respondents are listed in Table 1. The majority of respondents (79 %) practiced at academic centers, and 63 % were in practice ≥10 years. Surgical training varied: 51 % surgical oncology, 44 % hepato-pancreato-biliary/ transplantation, and 5 % no fellowship. Respondents spent a median of 75 % of their effort delivering patient care. Respondents reported evaluating a median of 15 patients per month for any gastrointestinal malignancy, while the median number of patients specifically evaluated with colorectal liver metastasis was four per month. All respondents indicated that they currently perform both LR and ablation for CLM. Respondents reported an overall median annual procedure volume of 30 for LR versus 10 for ablation. The median procedure volumes for the specific indication of CLM were lower (resection 17 vs. ablation 5).

TABLE 1.

Practice characteristics of survey respondents

| Characteristic | Response | n or median | % or IQR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Practice type | Academic practice or university hospital staff | 158 | 79 % |

| Private practice or community hospital staff | 41 | 21 % | |

| Percentage of time spent on clinical patient care | 75 % | 60–90 % | |

| Years in practice | 12 | 6–19 | |

| Fellowship training | Hepato-pancreato-biliary | 54 | 25 % |

| Surgical oncology | 112 | 51 % | |

| Transplantation | 44 | 21 % | |

| No fellowship | 12 | 5 % | |

| No. of patients monthly evaluated for GI malignancy | 15 | 9–20 | |

| No. of patients monthly evaluated for CLM | 4 | 2–8 | |

| Annual liver procedure volumes for any indicationa | Liver resection | 30 | 10–50 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 10 | 5–20 | |

| Annual liver procedure volumes for CLMa | Liver resection | 17 | 9–30 |

| Radiofrequency ablation | 5 | 2–10 | |

| Proportion of CLM cases discussed at multidisciplinary tumor board | 80 % | 50–100 % |

N number of respondents, IQR interquartile range, GI gastrointestinal, CLM colon cancer liver metastasis

For nonzero volumes only

Responses to attitudinal questions regarding initial therapy for colorectal liver metastasis were assessed. The overwhelming majority (99 %) of respondents considered surgical resection to be potentially curative therapy for CLM. In contrast, only 67 % of respondents considered intraoperative ablation to be a potentially curative therapy for CLM. Overall, few respondents (10 %) considered intra-arterial therapy to be potentially curable; however, there was a difference among community (24 %) versus academic (6 %) surgeons in regard to this question (P <0.001). Although certain factors (size >5 cm, carcinoembryonic antigen >200 ng/ml, bilateral disease) had no effect on the respondents’ impression regarding the likelihood that the CLM may be curable (median score = 3), other factors (number >4, hilar lymph node metastasis, resectable extrahepatic disease) had a modest effect on the respondents’ impression that such disease was likely incurable (median score = 2) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Response to attitudinal questions regarding initial therapy for CLM

| Question | Median response (1–5) or n (%) | IQR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In general, do you prefer immediate liver resection or neoadjuvant preoperative chemotherapy as the initial therapy for patients with CLEARLY RESECTABLE colon cancer liver metastasis? | ||||

| Liver resection | 3 | Neoadjuvant | 1–4 | |

| In general, if you do recommend neoadjuvant therapy for CLEARLY RESECTABLE colon cancer liver metastasis do you prefer the administration of cytotoxic agents alone (i.e., oxaliplatin or irinotecan-based therapies) or cytotoxic agents plus a biologic agent (i.e., bevacizumab or cetuximab)? | ||||

| Cytotoxic alone | 3 | Cytotoxic + biologic | 2–4 | |

| In general, if you do recommend neoadjuvant therapy for CLEARLY RESECTABLE colon cancer liver metastasis do you prefer to treat to “maximal response” or a short predetermined course (4–6 cycles)? | ||||

| Maximal response | 5 | Short course | 4–5 | |

| In general, if you do recommend preoperative therapy for UNRESECTABLE BUT POTENTIALLY CONVERTIBLE colon cancer liver metastasis do you prefer the administration of cytotoxic agents alone (i.e., oxaliplatin or irinotecan-based therapies) or cytotoxic agents plus a biologic agent (i.e., bevacizumab or cetuximab)? | ||||

| Cytotoxic alone | 5 | Cytotoxic + biologic | 3–5 | |

| In general, if you do recommend preoperative therapy for UNRESECTABLE BUT POTENTIALLY CONVERTIBLE colon cancer liver metastasis do you prefer to treat to “maximal response” or do you prefer to stop chemotherapy when the patient has been “converted” to being resectable? | ||||

| Maximal response | 5 | Converted | 2–5 | |

| In general, how do each of the following factors affect your clinical impression regarding the likelihood that the colon cancer liver metastasis is CURABLE? | ||||

| Likely incurable | Likely curable | |||

| CLM size >5 cm | 3 | 3–4 | ||

| CEA >200 ng/ml | 3 | 2–3 | ||

| Bilateral/bilobar disease | 3 | 2–3 | ||

| CLM >4 in number | 2 | 2–3 | ||

| Hilar LN metastasis | 2 | 1–2 | ||

| Resectable extrahepatic disease | 2 | 1–3 | ||

| When a patient presents with SYNCHRONOUS disease with resectable liver metastasis and an ASYMPTOMATIC colon cancer primary tumor, your preferred INITIAL course of therapy is: | ||||

| Surgery first | 2 | Chemotherapy first | 1–3 | |

| What do you consider “OPTIMAL” surgical therapy for patients with a solitary, small <3 cm colon cancer liver metastasis? | ||||

| Radiofrequency ablation | 5 | Liver resection | 5–5 | |

| Do you consider surgical resection to be a potentially curative therapy for colon cancer liver metastasis? | ||||

| Yes | 197 (99 %) | |||

| No | 2 (1 %) | |||

| Do you consider intraoperative ablation to be a potentially curative therapy for colon cancer liver metastasis? | ||||

| Yes | 133 (67 %) | |||

| No | 66 (33 %) | |||

| Do you consider intra-arterial therapy (e.g., yttrium-90, TACE, TAE) to be a potentially curative therapy for colon cancer liver metastasis? | ||||

| Yes | 19 (10 %) | |||

| No | 180 (90 %) | |||

All responses on Likert scale from 1 to 5. Median responses indicated

N number of respondents, CLM colon cancer liver metastasis, IQR interquartile range, CEA carcinoembryonic antigen, LN lymph node

When asked to indicate their general preferences for initial surgery versus neoadjuvant chemotherapy on a 1–5 Likert scale, there was relative equipoise among respondents with a median score of 3. When neoadjuvant therapy was recommended, there was similar equipoise among respondents (median score = 3) regarding whether to treat with cytotoxic chemotherapy alone or cytotoxic chemotherapy plus a biologic agent (e.g., bevacizumab or cetuximab). In contrast, most respondents strongly favored adding a biologic agent to cytotoxic chemotherapy if the patient had unresectable but potentially convertible liver metastasis (median score = 5). Respondents overwhelming agreed that preoperative chemotherapy should be stopped before achieving a maximal response. Specifically, among patients with resectable disease respondents strongly favored (median score = 5) short course therapy, while among patients with unresectable but potentially convertible liver metastasis respondents strongly favored stopping chemotherapy once the patient was resectable (median score = 5).

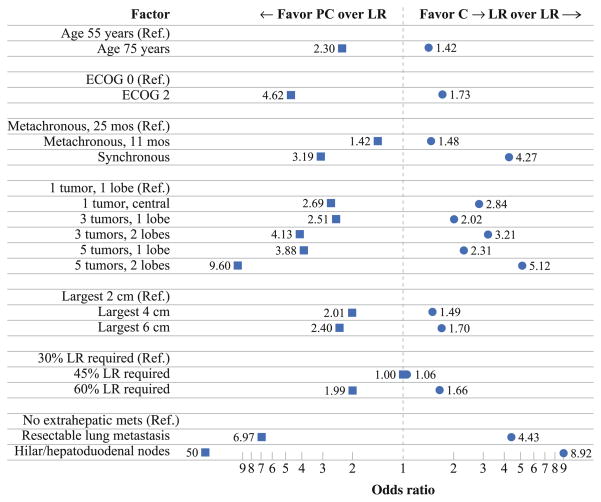

The clinical factors used to generate the conjoint tasks/ case scenarios are detailed in Table 3. Respondents were asked to assume that all patients were chemo-naïve, were at standard risk of chemotherapy-associated toxicities, and had no clinical or social factors that would preclude any of the available therapeutic options. In regression analyses, all clinical factors demonstrated statistically significant effects on the choice between LR, C → LR, and PC. Although each factor affected choice of CLM therapy, the relative impact differed (Fig. 1). Tumor presentation, tumor number and location, and the presence of extrahepatic disease had the largest effects on choice of therapy (Table 4). Chemotherapy was more likely to be recommended for patients who presented with synchronous disease. Specifically, synchronous versus metachronous CLM presentation increased the choice of C → LR (OR 4.27) and PC (OR 3.10) versus LR (P <0.001). Similarly, tumor number and location of liver metastasis increased the choice of chemotherapy versus immediate LR. For patients with more extensive intrahepatic disease (i.e., 5 tumors, both lobes) respondents strongly favored C → LR (OR 5.12) and PC (OR 9.60) versus LR (P <0.001). The factor that was most associated with a recommendation against LR was the presence of extrahepatic disease. The presence of hilar lymph node disease was associated with a strong aversion to LR, with surgeons more likely to choose C → LR (OR 8.92) or PC (OR 49.9) (P <0.001). Interestingly, even the presence of a resectable solitary lung metastasis strongly deterred choice of LR with respondents favoring C → LR (OR 4.43) or PC (OR 6.97) (P <0.001). Although other factors such as patient age, tumor size, and extent of resection affected choice of therapy, the relative size of these effects was modest.

TABLE 3.

Factors used in case scenarios

| Factor | Level |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55 |

| 75 | |

| ECOG performance status | 0 (fully active, able to carry on all predisease performance without restriction) |

| 2 (ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities, up and about more than 50 % of waking hours) | |

| Tumor presentation | Metachronous presentation with colon primary removed 25 months ago, adjuvant chemotherapy completed after colon resection |

| Metachronous presentation with colon primary removed 11 months ago, adjuvant chemotherapy completed after colon resection | |

| Synchronous presentation with colon primary removed 1 month ago, no chemotherapy given | |

| Tumor number and location | 1 tumor in a single lobe of the liver |

| 1 tumor centrally located in the liver | |

| 3 tumors in a single lobe of the liver | |

| 3 tumors in both lobes of the liver | |

| 5 tumors in a single lobe of the liver | |

| 5 tumors in both lobes of the liver | |

| Tumor size (largest metastasis) (cm) | 2 |

| 4 | |

| 6 | |

| Extent of resection required to remove all metastatic disease | 30 % of liver |

| 45 % of liver | |

| 60 % of liver | |

| Extrahepatic disease | No extrahepatic disease |

| Resectable solitary lung metastasis | |

| Metastatic disease to the hilar/hepato-duodenal lymph nodes |

ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

FIG. 1.

Although each factor affected choice of CLM therapy, the relative impact differed. Tumor presentation, tumor number and location, and presence of extrahepatic disease had the largest effects on choice of therapy. Ref. referent

TABLE 4.

Clinical factors that are determinants of choice of therapy

| Factor | C → LR vs. LR

|

PC vs. LR

|

PC vs. C→ LR

|

P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 55 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| 75 | 1.42 | 1.13–1.79 | 2.30 | 1.62–3.26 | 1.62 | 1.23–2.14 | |

| ECOG performance status | |||||||

| 0 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| 2 | 1.73 | 1.34–2.23 | 4.62 | 2.96–7.24 | 2.68 | 1.85–3.88 | |

| Tumor presentation (month) | |||||||

| Metachronous, 25 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| Metachronous, 11 | 1.48 | 1.11–1.96 | 1.42 | 0.93–2.16 | 0.96 | 0.66–1.40 | |

| Synchronous | 4.27 | 2.94–6.21 | 3.10 | 1.88–5.11 | 0.73 | 0.48–1.09 | |

| Tumor number and location | |||||||

| 1 tumor, single lobe | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| 1 tumor, centrally located | 2.84 | 1.96–4.13 | 2.69 | 1.50–4.85 | 0.95 | 0.58–1.56 | |

| 3 tumors, single lobe | 2.02 | 1.41–2.90 | 2.51 | 1.37–4.58 | 1.24 | 0.74–2.07 | |

| 3 tumors, both lobes | 3.21 | 2.14–4.81 | 4.13 | 2.16–7.88 | 1.29 | 0.73–2.27 | |

| 5 tumors, single lobe | 2.31 | 1.59–3.37 | 3.88 | 2.14–7.04 | 1.68 | 1.00–2.81 | |

| 5 tumors, both lobes | 5.12 | 3.26–8.04 | 9.60 | 5.08–18.2 | 1.88 | 1.11–3.17 | |

| Tumor size (largest metastasis) (cm) | |||||||

| 2 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| 4 | 1.49 | 1.12–2.00 | 2.01 | 1.31–3.08 | 1.34 | 0.95–1.89 | |

| 6 | 1.70 | 1.26–2.29 | 2.40 | 1.62–3.54 | 1.41 | 1.00–1.99 | |

| Extent of resection required (%) | |||||||

| 30 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 0.002 | |||

| 45 | 1.06 | 0.81–1.39 | 0.94 | 0.62–1.43 | 0.89 | 0.63–1.27 | |

| 60 | 1.66 | 1.23–2.23 | 1.99 | 1.32–2.99 | 1.20 | 0.84–1.71 | |

| Extrahepatic disease | |||||||

| None | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| Resectable solitary lung | 4.43 | 3.24–6.04 | 6.97 | 4.30–11.3 | 1.57 | 1.02–2.43 | |

| Hilar/hepato-duodenal nodes | 8.92 | 6.00–13.3 | 49.9 | 28.4–87.8 | 5.60 | 3.62–8.64 | |

LR immediate liver resection, C → LR preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery, PC palliative chemotherapy, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, Ref. referent, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

Additional regression analyses were then performed to assess the impact of nonclinical factors, after adjustment for clinical characteristics, on choice of therapy (Table 5). Specifically, we were interested in examining possible physician-related determinants of choice of therapy for CLM. After controlling for clinical factors, surgeons with more years in practice were more likely to choose PC over C → LR. In addition, surgical oncology-trained surgeons were more likely than hepato-pancreato-biliary/transplantation-trained surgeons to choose C → LR (OR 2.53) or PC (OR 4.15) over LR (P <0.001). Other provider- and institution-level factors such as number of patients evaluated per month and practice type did not affect the choice of therapy (both P >0.05).

TABLE 5.

Nonclinical factors (adjusted for clinical factors) that are determinants of choice of therapy

| Factor | C → LR vs. LR

|

PC vs. LR

|

PC vs. C → LR

|

P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | OR | 95 % CI | ||

| Practice type | |||||||

| Private | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 0.95 | |||

| Academic | 1.08 | 0.67–1.74 | 1.09 | 0.53–2.23 | 1.01 | 0.58–1.75 | |

| Years in practice (years) | |||||||

| <10 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 0.005 | |||

| ≥10 | 0.70 | 0.46–1.06 | 1.36 | 0.70–2.66 | 1.94 | 1.18–3.18 | |

| Fellowship training | |||||||

| Hepato-pancreato-biliary or transplantation | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | <0.001 | |||

| Surgical oncology | 2.53 | 1.66–3.87 | 4.15 | 2.07–8.29 | 1.64 | 0.92–2.91 | |

| No fellowship training | 2.06 | 0.95–4.49 | 2.94 | 0.81–10.7 | 1.43 | 0.53–3.81 | |

| Proportion of CLM cases discussed at multidisciplinary tumor board (%) | |||||||

| <50 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 0.03 | |||

| ≥50 | 1.16 | 0.75–1.81 | 0.58 | 0.30–1.13 | 0.50 | 0.30–0.84 | |

| No. of patients monthly evaluated for CLM | |||||||

| <8 | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | 0.44 | |||

| ≥8 | 1.03 | 0.66–1.60 | 0.72 | 0.34–1.56 | 0.70 | 0.40–1.23 | |

LR immediate liver resection, C → LR preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery, PC palliative chemotherapy, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, Ref. referent, CLM colon cancer liver metastasis

DISCUSSION

This is the first nationwide study to define the relative impact of key clinical- and provider-level factors on choice of therapy for colorectal liver metastasis. Variation in choice of therapy in colorectal liver metastasis has been poorly documented. Choice of therapy may depend both on clinical factors as well as surgeon characteristics. However, the factors influencing how providers arrive at decisions regarding the management of colorectal liver metastasis have not been previously studied. This study is important because it is the first to analyze nationwide surgical decision making in colorectal liver metastasis using physician-based decision-making analyses. By means of conjoint analysis methodology, we were able to quantify the relative impact of clinical factors on choice of therapy. We found that synchronous presentation and the presence of extra-hepatic disease had the largest effect on choice of therapy. Interestingly, we also noted a significant effect of surgeon subspecialty training on decision making, with surgical oncology–trained clinicians being more likely to utilize chemotherapy in the treatment plan. The present study is noteworthy in that it provides quantitative data on the relative contribution of clinical factors and surgeon specialty in decision making for colorectal liver metastasis.

A particular strength of our study was the use of conjoint analysis to assess provider decision making. Conjoint methodology has been validated as a means to help elucidate predictors of real-world decisions.12 Conjoint analysis has traditionally been used in market research to understand how markets or consumers value different elements of a product. The principal advantage of conjoint methodology is that it allows a decision to be broken down into its constituent parts and the value of each factor in driving the respondent’s decision determined. Specifically, by presenting respondents with a series of clinical vignettes incorporating multiple factors of interest, the relative importance of these factors in their clinical decisions can be elicited. Conjoint analysis also has the advantage of allowing the exclusion of factors that are not of clinical interest but might confound other analyses of clinical decision making.16 Previous data have shown that simple physician surveys regarding treatment decisions and stated preferences correlate poorly with actual clinical behavior.11,17–19 In contrast, conjoint analysis can elicit the factors driving clinical decisions better than physician introspection alone and therefore more strongly simulates real-life decisions.20,21

In the present study, we found that the choice of surgical therapy for colorectal liver metastasis varied widely. Different clinical characteristics influenced treatment planning and had varying degrees of importance in the selection of therapy. We noted that the timing of metastatic disease presentation, tumor number and location, and the presence of extrahepatic disease had the largest effects on choice of therapy. Our finding that there was a strong aversion to LR in the setting of these specific clinical factors correlates with the traditional sentiment among surgeons that these cohorts of patients have poor outcomes after surgery.5–7 In addition, our data demonstrate the increasing preference among many surgeons to utilize chemotherapy rather than immediate surgery for high-risk patients. In the only other conjoint analysis looking at decision making for colorectal metastasis, Langenhoff et al. reported on a very small (n = 25) single-center experience from the Netherlands.9 In this study, the authors similarly noted that involvement of both lobes and location of metastases were the most important factors affecting treatment planning. In the present study, we noted that location of metastases was indeed the strongest determinant of choice of therapy. Location of metastatic disease in the hilar lymph nodes was associated with a strong preference for PC over LR (OR 49.9).

Also notable was our finding that the presence of a resectable solitary lung metastasis strongly deterred choice of LR. Many clinicians consider the lung to be the extra-hepatic site of metastatic disease that is most potentially curable, especially among patients with a solitary lesion.22–24 Despite this, in this survey, surgeons were more inclined to choose PC rather than LR (OR 6.97) for patients with a resectable solitary lung lesion, as compared with patients who had no extrahepatic disease. These data emphasize the strong aversion some surgeons have to offering surgery to patients with colorectal metastasis, even in the setting of low-volume extrahepatic disease. Although our group and others have advocated for resection of hepatic and extrahepatic disease in well-selected patients, many surgeons remain skeptical of this therapeutic approach.25,26

In addition to analyzing clinical determinants of care, we identified nonclinical factors that strongly influence choice of therapy (Table 5). Virtually all data to date regarding receipt of therapy for most cancers have focused solely on patient- and tumor-specific factors that affect treatment recommendations. Variation in provider preferences—irrespective of clinical factors—may also be important. Previous data have suggested that physician subspecialty may affect treatment recommendations and survival of patients with myocardial infarction.27 Other data have also noted differences in clinical outcomes and resource utilization on a general medical service based on inpatient physician specialty.28 The effect of physician subspecialty on receipt of cancer care, however, has been poorly studied.

Our group previously reported that choice of therapy for early hepatocellular carcinoma was strongly associated with surgeon subspecialty—even more so than some clinical factors.13 In the present study, we expand on our previous work and examine the role of surgical subspecialty on receipt of therapy for patients with colorectal liver metastasis. Of note, we found that certain surgeon-specific factors played a role that was equally important to clinical factors in determining the preferred initial therapy for CLM. After controlling for clinical factors, surgeons with more years in practice were more likely to choose PC over C → LR. Surgical subspecialty had an even greater impact on choice of therapy. Specifically, surgical oncology-trained surgeons were significantly more likely to use chemotherapy as part of their recommended therapeutic plan compared with hepato-pancreato-biliary/transplantation-trained surgeons, who more often preferred immediate resection. These data begin to elucidate some of the underlying root causes for provider-specific variation of care.

Several limitations of our study should be considered. First, as noted in our previous work, this study assessed stated preferences for surgical therapy as opposed to surgeons’ actual practice patterns.13 Although this allowed us to standardize the case scenarios and eliminate some confounding factors, it had the disadvantage of assessing decision making in a relatively idealized context. Previous work, however, has demonstrated that this approach results in valid assessments of clinical decision making.16 A second limitation is that we do not know the characteristics of survey nonrespondents, and therefore the data may suffer from reporting bias.

In conclusion, the choice of surgical therapy for CLM varies widely. The variability in surgical decision making for colorectal liver metastasis is associated with both clinical factors and surgeon specialty. Although certain clinical factors such as patient age, tumor size, and extent of resection have only a modest effect on a surgeon’s decision to offer resection, other factors such as the timing of disease presentation and the presence of extrahepatic disease have a dramatic effect. In addition, while these clinical factors influence choice of therapy, surgical sub-specialty and physician experience are also important determinants of care. In fact, surgical subspecialty was noted to be a stronger determinant of choice of therapy than some clinical factors. In aggregate, our data emphasize the ongoing need to better understand how clinicians determine which therapies to offer patients. Only through such understanding of physician decision making can we hope to increase compliance with evidence-based recommendations and improve the quality and standardization of care delivered to cancer patients. Future studies will need to investigate discrete choice models that include other stakeholders (e.g., medical oncology) and to explore interventions to improve standardization of care for patients with colorectal liver metastasis.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1245/s10434-012-2564-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Pawlik TM, Choti MA. Surgical therapy for colorectal metastases to the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1057–77. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pawlik TM, Choti MA. Shifting from clinical to biologic indicators of prognosis after resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. Curr Oncol Rep. 2007;9:193–201. doi: 10.1007/s11912-007-0021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawlik TM, Vauthey JN. Surgical margins during hepatic surgery for colorectal liver metastases: complete resection not millimeters defines outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:677–9. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9703-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Sahaf O, Al-Azawi D, Al-Khudairy A, et al. Referral patterns of patients with liver metastases due to colorectal cancer for resection. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:79–82. doi: 10.1007/s00384-008-0561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–18. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nordlinger B, Guiguet M, Vaillant JC, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal carcinoma metastases to the liver. A prognostic scoring system to improve case selection, based on 1568 patients. Association Francaise de Chirurgie. Cancer. 1996;77:1254–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hofmann A. Hepatic metastases from colorectal carcinoma: impact of surgical resection on the natural history. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1241–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Jong MC, Pulitano C, Ribero D, et al. Rates and patterns of recurrence following curative intent surgery for colorectal liver metastasis: an international multi-institutional analysis of 1669 patients. Ann Surg. 2009;250:440–8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b4539b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langenhoff BS, Krabbe PF, Ruers TJ. Computer-based decision making in medicine: a model for surgery of colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33(Suppl 2):S111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kee F, McDonald P, Kirwan JR, et al. The stated and tacit impact of demographic and lifestyle factors on prioritization decisions for cardiac surgery. QJM. 1997;90:117–23. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/90.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirwan JR, Currey HL, Brooks PM. Measuring physicians’ judgment—the use of clinical data by Australian rheumatologists. Aus N Z J Med. 1985;15:738–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bridges JF. Stated preference methods in health care evaluation: an emerging methodological paradigm in health economics. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2003;2:213–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathan H, Bridges JF, Schulick RD, et al. Understanding surgical decision making in early hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:619–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedayat A, Sloane N, Stufken J. Orthogonal arrays: theory and application. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kucirka LM, Namuyinga R, Hanrahan C, et al. Formal policies and special informed consent are associated with higher provider utilization of CDC high-risk donor organs. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:629–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Timmermans DR, Gooszen AW, Geelkerken RH, et al. Analysis of the variety in surgeons’ decision strategies for the management of left colonic emergencies. Med Care. 1997;35:701–13. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199707000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirwan JR, Chaput de Saintonge DM, Joyce CR, et al. Inability of rheumatologists to describe their true policies for assessing rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1986;45:156–61. doi: 10.1136/ard.45.2.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heatherton TF, Mahamedi F, Striepe M, et al. A 10-year longitudinal study of body weight, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms. J Abnorm Psychology. 1997;106:117–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viney R, Lancsar E, Louviere J. Discrete choice experiments to measure consumer preferences for health and healthcare. Expert Rev Pharmacoeconom Outcomes Res. 2002;2:319–26. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2.4.319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips KA, Maddala T, Johnson FR. Measuring preferences for health care interventions using conjoint analysis: an application to HIV testing. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1681–705. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.01115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ijzerman MJ, van Til JA, Snoek GJ. Comparison of two multi-criteria decision techniques for eliciting treatment preferences in people with neurological disorders. Patient. 2008;1:265–72. doi: 10.2165/1312067-200801040-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yedibela S, Klein P, Feuchter K, et al. Surgical management of pulmonary metastases from colorectal cancer in 153 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1538–44. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girard P, Ducreux M, Baldeyrou P, et al. Surgery for lung metastases from colorectal cancer: analysis of prognostic factors. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2047–53. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iizasa T, Suzuki M, Yoshida S, et al. Prediction of prognosis and surgical indications for pulmonary metastasectomy from colo-rectal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:254–60. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pulitano C, Bodingbauer M, Aldrighetti L, et al. Liver resection for colorectal metastases in presence of extrahepatic disease: results from an international multi-institutional analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1380–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1459-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elias D, Liberale G, Vernerey D, et al. Hepatic and extrahepatic colorectal metastases: when resectable, their localization does not matter, but their total number has a prognostic effect. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:900–9. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frances CD, Shlipak MG, Noguchi H, et al. Does physician specialty affect the survival of elderly patients with myocardial infarction? Health Serv Res. 2000;35:1093–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parekh V, Saint S, Furney S, et al. What effect does inpatient physician specialty and experience have on clinical outcomes and resource utilization on a general medical service? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:395–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30298.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.