Abstract

The peptide transmitter neurotensin (NT) exerts diverse neurochemical effects that resemble those seen after acute administration of antipsychotic drugs (APDs). These drugs also induce NT expression in the striatum; this and other convergent findings have led to the suggestion that NT may mediate some APD effects. Here, we demonstrate that the ability of the typical APD haloperidol to induce Fos expression in the dorsolateral striatum is markedly attenuated in NT-null mutant mice. The induction of Fos and NT in the dorsolateral striatum in response to typical, but not atypical, APDs has led to the hypothesis that the increased expression of these proteins is mechanistically related to the production of extrapyramidal side effects (EPS). However, we found that catalepsy, which is thought to reflect the EPS of typical APDs, is unaffected in NT-null mutant mice, suggesting that NT does not contribute to the generation of EPS. We conclude that NT is required for haloperidol-elicited activation of a specific population of striatal neurons but not haloperidol-induced catalepsy. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that endogenous NT mediates a specific subset of APD actions.

Schizophrenia is a debilitating psychiatric disorder of high prevalence characterized by a number of symptoms, including social isolation, cognitive deficits, and episodic psychotic symptoms. In many patients, the florid (positive) psychotic symptoms can be effectively treated with antipsychotic drugs (APDs); however, treatment with conventional APDs is often accompanied by extrapyramidal motor side effects (EPS). The introduction of atypical APDs with a decreased propensity to produce EPS has resulted in these agents becoming the first line of treatment for schizophrenia, particularly because atypical APDs are effective with many patients who fail to respond to conventional APDs and may treat certain cognitive deficits (1, 2). All clinically effective APDs exhibit a significant affinity for dopamine D2 receptors, supporting the hypothesis that an increase in central dopaminergic tone contributes to schizophrenic symptoms, particularly psychotic symptoms (3–5). The mechanisms underlying the therapeutic actions of APDs and the generation of EPS by typical APDs remain poorly understood. However, the ability of these drugs to induce the expression of Fos (the protein product of the immediate early gene c-fos) and neurotensin (NT) has led to the suggestion that changes in gene expression might be responsible for certain APD actions.

Both typical and atypical APDs increase Fos and NT expression in certain brain regions, such as the nucleus accumbens. In contrast, typical—but not atypical—APDs markedly increase Fos and NT expression in neurons in the caudate-putamen (6–11). The ability of typical APDs to increase dramatically NT expression in the dorsolateral caudate-putamen has led to the suggestion that NT may be involved mechanistically in the production of EPS. Typical APDs exhibit a higher in vivo occupancy of striatal D2 receptors than do atypical APDs such as clozapine, and this difference is thought to underlie the differences in EPS liability between the different types of APDs (12). Interestingly, Fos seems to mediate, at least in part, haloperidol induction of NT gene expression in the dorsolateral caudate-putamen (13–15).

The ability of APDs to induce NT expression coupled with the similarities in the neurochemical effects of APDs and centrally administered NT has led to the hypothesis that alterations in central NT subserve certain symptoms in schizophrenia (16, 17). Consistent with this hypothesis is the observation that cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of NT are lower in schizophrenic subjects than in controls, particularly in patients with prominent negative symptoms, and that they normalize after APD treatment (18, 19). However, studies of NT involvement in dopamine function and schizophrenia have been hampered by the lack of suitable NT receptor antagonists. Three NT receptors have been cloned, including two G protein-coupled receptors and the intracellular sortilin protein, and another receptor has been suggested based on pharmacological studies (20, 21). Although NT antagonists have been developed and have been useful for studies of the high-affinity NT receptor (NTR-1), they behave as agonists at the low-affinity NTR-2 (22).

To investigate further the various functions of NT, including its involvement in subserving certain actions of APDs, we used gene-targeting methods to disrupt the mouse gene encoding NT and the related hexapeptide neuromedin N (the NT/N gene). In these null mutant mice, haloperidol induction of Fos in the dorsolateral and central caudate-putamen, but not the nucleus accumbens, is markedly attenuated, whereas clozapine induction of Fos is unaffected.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Restriction endonucleases and other enzymes were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals and New England Biolabs; Taq DNA polymerase was purchased from Sigma. Haloperidol was also purchased from Sigma. Clozapine was purchased from Research Biochemicals (Natick, MA). Fos-specific antibody (AB5) was purchased from Oncogene Science. [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol; 1 Ci = 37 GBq) was purchased from New England Nuclear.

NT Gene Targeting Procedures.

NT/N genomic clones were isolated from a λEMBL4 library derived from D3 mouse embryonic stem (ES) cell DNA by using a canine NT/N cDNA probe (23), and the entire NT/N gene was sequenced (GenBank accession number AF348489). The targeting plasmid was constructed by using a multistep cloning procedure. A 1.1-kb 5′ mouse NT/N gene fragment ending at the initiator methionine codon (nucleotides 642-1709) was PCR-amplified from ES cell genomic DNA by using the primers 5′-GGGGTCTAGATGTCTAAAGGTACAGTCTGC-3′ and 5′-GGGGCCATGGTCTCTCAGCCTTCTGACAAGC-3′.

The PCR fragment was digested with XbaI and NcoI and cloned upstream of the β-galactosidase (β-gal) gene in the plasmid pnlacF (24) cut with the same enzymes. The polylinker HindIII site in this construct was converted to a NotI site by ligation of NotI linkers to create pNT5′nlacF. The plasmid pPNT (25) was digested with BamHI, filled in with the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase, and subsequently digested with NotI, and the 1.7-kb PGK-neo fragment was gel-isolated. pNT5′nlacF was digested with SphI, filled in with Klenow fragment, subsequently digested with NotI, and ligated with the PGK-neo fragment to yield pNT5′nlacFneo. A PstI/MscI NT/N gene fragment (nucleotides 2265–8117) was cloned into pBluescript II KS+ (Stratagene) digested with XbaI, filled in with Klenow fragment, and subsequently digested with PstI. The NT fragment was excised by digestion with XhoI and NotI and cloned into NotI/XhoI-digested pNT5′nlacFneo to yield the targeting plasmid (Fig. 1A).

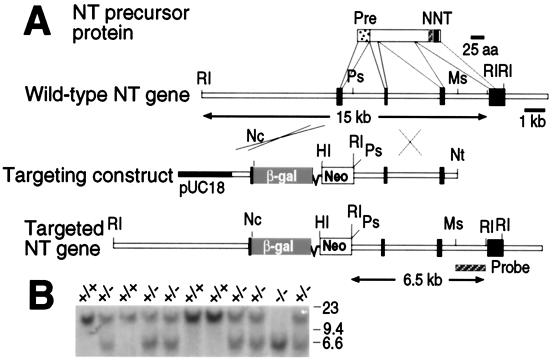

Figure 1.

Generation of NT mutant mice. (A) Strategy for NT/N gene disruption. The NT/N precursor protein is depicted; the signal sequence (Pre, dotted), neuromedin N (N, hatched), and NT (NT, black) coding domains, and the corresponding exons of the mouse NT/N gene are indicated. Mouse NT/N gene fragments were inserted on either side of β-gal and PGK-Neo genes in the targeting construct, and homologous recombination resulted in the targeted NT gene structure shown at the bottom. pUC18, cloning vector (black); RI, EcoRI; Ps, PstI; Ms, MscI; Nc, NcoI; HI, BamHI; Nt, NotI. (B) Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-digested tail DNA derived from the progeny of two NT+/− mice. The 15- and 6.5-kb EcoRI fragments identified by the 32P-labeled 3′ probe depicted in A represent the wild-type and targeted alleles, respectively. The positions of HindIII-digested λ DNA size markers are indicated.

The targeting plasmid was linearized with NotI and transfected into J1 ES cells by electroporation (26). DNA was prepared from G418-resistant clones and analyzed by Southern blotting to identify correctly targeted clones. Two correctly targeted ES cell lines were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts to generate chimeric progeny; one (ES 164) yielded chimeras that produced agouti progeny when mated with C57BL/6J partners. Tail DNA was prepared from agouti pups and genotyped by Southern blotting. Heterozygous progeny were mated to produce wild-type and NT−/− mice, and these were randomly bred to produce mice for experiments. Although the β-gal gene was fused to the NT/N gene initiator methionine codon in the targeting construct, we were unable to detect β-gal activity in brain sections either by 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-d-galactoside staining or immunohistochemical detection by using a β-gal-specific antibody.

RNA Extraction and Northern Blotting.

RNA was prepared from various tissues by extraction with guanidinium isothiocyanate/phenol/chloroform, and polyadenylated RNA was selected by using oligo(dT)-cellulose. Northern analysis was performed with 10 μg of polyadenylated RNA from each tissue and 32P-labeled cDNA probes. Dynorphin (515-bp BamHI fragment from exon 4) and dopamine D2 receptor (752-bp BamHI/EcoRV fragment from exon 7) clones were PCR-amplified from mouse ES cell DNA for use as probes. An NsiI/EcoRI fragment spanning exon 4 (nucleotides 9522–10317) of the mouse NT/N gene was subcloned into pGEM4 (Promega) that had been digested with PstI and EcoRI for use as a probe. Probes for human substance P (27), rat enkephalin (28), and rat tyrosine hydroxylase (29) were generated as described.

NT RIA.

Tissues were extracted with acid/acetone, aliquots (0.5 g) were fractionated by HPLC, and NT was quantitated by RIA using an N-terminal NT antiserum (BSA-8) as described (30, 31). The assay sensitivity was >0.5 fmol.

Haloperidol and Clozapine Induction of Fos.

Mice were raised under a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. Age-matched adult (>12 weeks) mice were injected i.p. with haloperidol (1 mg/kg), clozapine (20 mg/kg), or pH-matched vehicle, and 2 h later were rapidly anesthetized with isoflurane and perfused with 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, followed by 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde/0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer. Immunohistochemical analysis of c-Fos was performed as described by using a rabbit Fos antibody (AB5, diluted 1:20,000; Oncogene Science; ref. 6). An observer blind to both genotype and treatment counted Fos-positive neurons after a rectangular grid was superimposed on the region of interest (total area = 0.085 mm2). The data are expressed as Fos-positive neurons per mm2 and were analyzed by ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis when indicated with the Bonferroni multiple comparisons test.

Catalepsy Measurements.

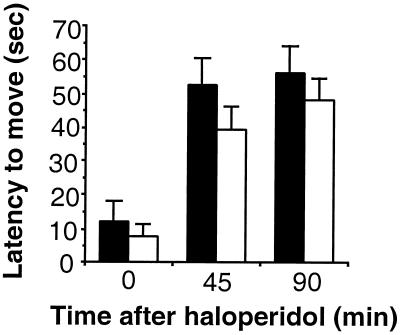

Catalepsy scores were defined as the latency of the mice to move all four paws when placed on a vertical wire mesh grid. Baseline catalepsy was measured immediately after haloperidol injection (1 mg/kg); measurements were repeated at 45 and 90 min after injection (maximum score = 90 sec). The data were analyzed by ANOVA.

Results

Generation and Characterization of NT Knockout Mice.

The targeting strategy depicted in Fig. 1A was used to generate mice in which a portion of the NT/N gene that includes the precursor protein signal sequence and part of the first intron was deleted. The disrupted allele had the anticipated structure as determined by Southern blot analysis of EcoRI-digested genomic DNA using a 3′ probe located downstream of the sequences used in the targeting plasmid (Fig. 1A). The targeting plasmid introduces a new EcoRI site that gives rise to a 6.5-kb EcoRI fragment that clearly can be distinguished from the 15-kb EcoRI fragment derived from the wild-type NT/N gene (see Fig. 1B). PCR analysis also was used to verify that the 5′ end of the targeted locus had the correct structure (data not shown). Heterozygous mating pairs produced NT−/− mice with a normal Mendelian distribution, indicating that the NT mutation does not result in embryonic lethality (Fig. 1B).

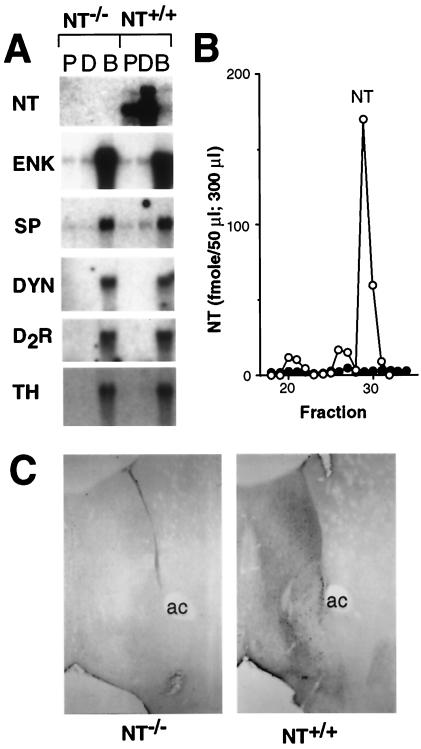

The NT/N gene deletion results in a null mutation by several criteria. NT/N mRNA is not detectable by Northern blot analysis of poly(A)+ RNA from the proximal and distal small intestine and brain of NT−/− mice (Fig. 2A). In contrast, dynorphin, substance P, enkephalin, tyrosine hydroxylase, and dopamine D2 receptor mRNA levels are not altered in the brains of NT−/− mice. RIA of HPLC-fractionated brain extracts failed to detect NT in the brains of NT−/− mice (<0.1% wild-type level, Fig. 2B). Similarly, NT-like immunoreactivity was not detectable in brain sections from NT−/− mice (Fig. 2C). In addition, NT was not detected in extracts of proximal and distal small intestine from NT−/− mice (data not shown). Despite the lack of NT, the null mutant mice did not differ from wild type in general appearance, gross anatomy, body weight, reproduction, or overt behavior.

Figure 2.

NT−/− mice do not express NT. (A) Northern analysis of poly(A)+ RNA (10 μg) isolated from the proximal small intestine (P), distal small intestine (D), and brain (B) from NT−/− and NT+/+ mice. The blots were hybridized with 32P-labeled probes for NT, enkephalin (ENK), substance P (SP), dynorphin (DYN), dopamine D2 receptor (D2R), and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH). (B) NT was quantitated by RIA with an N-terminally directed NT antiserum after HPLC-fractionation of brain extracts from NT−/− (●, fmol/300 μl) and NT+/+ (○, fmol/50 μl) mice. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of NT expression in coronal brain sections from NT−/− (Left) and NT+/+ (Right) mice with a C-terminally directed NT antibody.

Haloperidol Induction of Striatal Fos Is Markedly Attenuated in NT Knockout Mice.

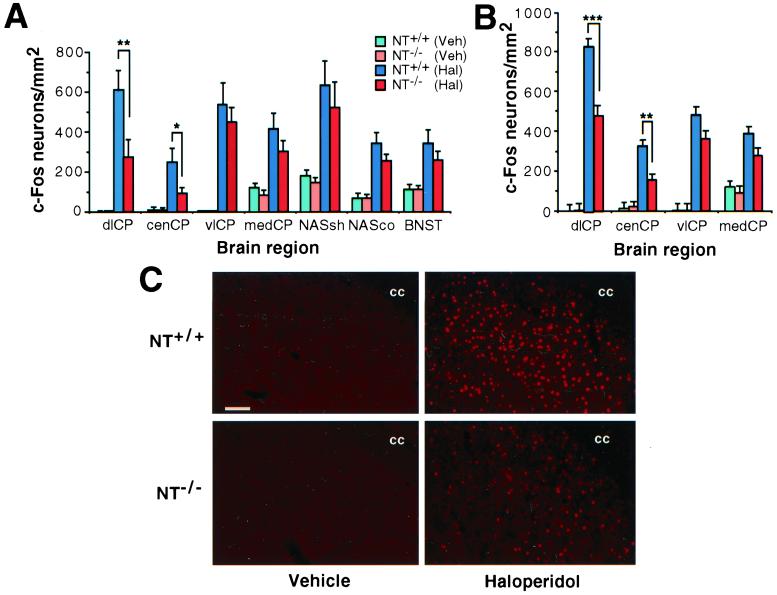

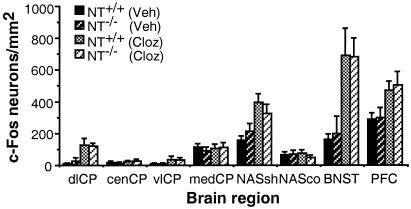

Because NT has actions similar to APDs, we investigated whether APD-induced Fos expression was altered in NT−/− mice. Consistent with previous results, acute administration of haloperidol (1.0 mg/kg) dramatically increased the numbers of Fos-like immunoreactive (-li) neurons in the striatal complex of wild-type mice, including both the caudate-putamen and nucleus accumbens, as well as several other brain regions (Fig. 3 A–C). There was a marked regionally specific alteration in the number of Fos-li neurons in the caudate-putamen in NT−/− mice: the numbers of Fos-li neurons decreased in the dorsolateral and central caudate-putamen but not other striatal sectors (Fig. 3 A–C). This attenuation extended throughout the length of the caudate, but was somewhat greater at intermediate (≈60%) compared with rostral (≈40%) levels (Fig. 3 A and B). Haloperidol-evoked Fos induction was similarly attenuated in both the dorsolateral [t(16) = 2.32, P = 0.037] and central [t(16) = 2.52, P = 0.022] striata of NT−/− mice generated from heterozygous mating pairs after backcrossing with C57BL/6J mice for five generations. There was no difference in the numbers of Fos-li neurons in the shell and core compartments of the nucleus accumbens and in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis of haloperidol-treated wild-type and NT−/− mice. The Fos response to clozapine was also unaffected in NT−/− mice in any area examined (Fig. 4). These results indicate that NT plays an important role in the haloperidol-elicited activation of neurons in the dorsolateral and central caudate-putamen.

Figure 3.

Haloperidol induction of Fos is markedly attenuated in the dorsolateral and central caudate-putamen of NT−/− mice. (A) The number of Fos-positive neurons was quantitated after immunohistochemical detection of Fos in brain sections from NT+/+ (n = 10, Veh; n = 8, Hal) or NT−/− (n = 9, Veh; n = 7, Hal) mice that had been treated with either haloperidol (1 mg/kg) or pH-matched vehicle 2 h before perfusion. The mean (±SEM) number of Fos-positive neurons per mm2 is presented for the intermediate caudate-putamen (Bregma + 0.2), the nucleus accumbens (Bregma + 1.1 mm), and the bed nucleus (at the level of Bregma). dlCP, dorsolateral caudate-putamen; cenCP, central CP; vlCP, ventrolateral CP; medCP, medial CP; NASsh, nucleus accumbens shell; NASco, NAS core; BNST, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. (B) Fos-positive neurons in the rostral striatum (Bregma + 0.9 mm) in the same experiment as described in A. **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. (C) Immunofluorescent detection of Fos expression in the dorsolateral striatum of NT+/+ (Upper) and NT−/− (Lower) mice after the administration of either vehicle (Left) or haloperidol (Right). The position of the corpus collosum (cc) is indicated. (Bar = 100 μm.)

Figure 4.

Clozapine induction of Fos is unaltered in NT−/− mice. NT+/+ (n = 9, Veh; n = 6, Cloz) and NT−/− (n = 6, Veh; n = 6, Cloz) mice were injected with either clozapine (20 mg/kg) or pH-matched vehicle 2 h before perfusion. Fos-positive neurons were quantitated as described in the legend of Fig. 3. Abbreviations are as described for Fig. 3A plus PFC, prefrontal cortex.

Haloperidol-Induced Catalepsy Is Not Altered in NT Knockout Mice.

Typical APDs produce catalepsy, which has been used as a behavioral screen for EPS (32). Centrally administered NT also has been reported to produce catalepsy in mice (33) and this, combined with other evidence demonstrating that haloperidol induces NT expression in the dorsolateral striatum (10, 34, 35), has led to the hypothesis that NT may mediate haloperidol-induced catalepsy. To examine whether NT is required for catalepsy, wild-type and NT−/− mice were injected with haloperidol (1 mg/kg); catalepsy was assessed by placing the mice on a vertical wire mesh and measuring the amount of time required for the movement of all four paws (90 sec maximum). We found no significant differences between NT−/− and wild-type mice in either baseline catalepsy scores or in catalepsy measured 45 and 90 min after haloperidol challenge (Fig. 5), indicating that NT is not required for haloperidol-induced catalepsy.

Figure 5.

Haloperidol-induced catalepsy is unaffected in NT−/− mice. The latency to move all four paws after placement on a vertical wire grid was measured immediately after haloperidol administration (1 mg/kg) and at 45 and 90 min after injection. A maximal score of 90 sec was allowed. The mean latency to move was plotted (±SEM) for NT+/+ (black bars, n = 14) and NT−/− (white bars, n = 23) mice.

Discussion

Our studies reveal that NT (and/or neuromedin N) plays an important role in the haloperidol-elicited activation of certain striatal neurons. This result is consistent with the previous suggestion that NT has endogenous antipsychotic-like actions (16, 17). We observed an attenuation of the striatal Fos response to typical APD challenge only in the dorsolateral and central striatal sectors of NT−/− mice. In neither of these areas does clozapine induce Fos, and thus the lack of an effect of the NT knockout on clozapine-elicited Fos is not unexpected. The diminished striatal Fos response to haloperidol challenge in NT−/− mice indicates that NT is required for the activation of specific populations of striatal neurons by typical APDs. The possibility that this effect is caused by developmental or adaptive effects of the mutation is unlikely, because pretreatment with the NT antagonist SR 48692 also reduces haloperidol-elicited Fos induction in the rat dorsolateral but not in other striatal regions (36).

Regionally Distinct Changes in Fos Expression in NT−/− Mice.

The decrease in haloperidol-elicited Fos expression in the striatum exhibited a distinct regional pattern, being observed only in the dorsolateral and central—but not other—sectors of the striatum. This pattern corresponds well to the regional pattern of induction of NT/N gene expression by dopamine D2 receptor antagonists. Although few cells in the dorsolateral and central striata contain detectable NT/N mRNA or peptide under basal conditions, D2 receptor antagonists markedly increase the number of detectable NT neurons in these regions (10, 11, 37, 38). These findings suggest that intrinsic striatal NT neurons are present but exhibit a low basal degree of activity. It may be this population of striatal NT-containing neurons in which haloperidol fails to induce Fos in NT−/− mice.

This suggestion is consistent with several studies that have reported that D2 antagonists and other treatments that disrupt dopaminergic function result in the appearance of at least two distinct populations of NT neurons (38–42). One of these groups of NT cells is concentrated in the matrix compartment of the dorsomedial and ventrolateral striata; these cells rarely express Fos (38, 42). Another population of NT neurons located in the dorsolateral striatum that becomes apparent after haloperidol treatment projects to the globus pallidus almost exclusively (42), and most of that population expresses Fos (38, 43). We suggest that the reduction in Fos-like immunoreactive neurons observed in the dorsolateral and central striata of NT−/− mice reflects the involvement of the latter population of striatopallidal neurons. The previous estimate that ≈75% of the NT neurons seen in the dorsolateral striatum after D2 antagonist challenge express Fos (43) is in remarkably good agreement with our finding of a decrease of ≈65% in the number of dorsolateral striatal cells expressing Fos in NT−/− mice. It is unlikely that the decrease in Fos expression is caused by a structural loss of these dorsolateral NT neurons, because the same regionally specific pattern of suppression of haloperidol-elicited Fos induction is seen after pretreatment of rats with the NTR-1 antagonist SR 48692 (36).

Mechanisms Through Which NT Loss Could Attenuate Haloperidol-Elicited Striatal Fos Expression.

The ability of APDs such as haloperidol to induce Fos in the dorsal striatum involves multiple neurotransmitters (9). In particular, pretreatment with N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonists attenuates haloperidol-induced Fos expression (44–46), suggesting that D2 antagonist-evoked striatal glutamate release from cortical or thalamic afferents determines, in part, the Fos response. NTR-1 receptors do not appear to be present on intrinsic striatal neurons (47, 48) but are expressed in cortical pyramidal cells in layer V (47), suggesting that the absence of striatal NT in the null mutant mouse may lead to a loss of retrograde signaling and blunted glutamate release. This suggestion is consistent with the observation that intrastriatal infusion of NT increases extracellular glutamate levels, and that this effect is blocked by pretreatment with the NT receptor antagonist SR 48692 (49, 50). Whereas the observation that D2 antagonist administration results in the appearance of NT cells that were previously below detection threshold suggests that basal functional activity of these cells may be low, several in vivo microdialysis studies have found detectable levels of NT in the striatum (39, 51, 52), consistent with a tonic regulation of striatal function by NT.

NT and APD Actions.

In addition to the large body of literature relating NT to APD actions, clinical studies have suggested a decrease in NT concentrations in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of schizophrenic patients (18, 53, 54). Although some studies have not observed a statistically significant decrease in CSF NT concentrations in schizophrenic subjects, it seems that NT concentrations are significantly lower in patients with prominent negative symptoms and that NT levels normalize with APD treatment (18, 54). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that NT acts as an endogenous APD (16).

The induction of Fos and NT expression in the dorsolateral striatum in response to typical APDs has led to the suggestion that these changes may be responsible, at least in part, for the EPS associated with the therapeutic use of these drugs. However, haloperidol-induced catalepsy was not altered in NT knockout mice. This finding was somewhat surprising because Fos expression in the dorsolateral striatum is usually an accurate index of the cataleptic response, although exceptions have been reported (55). One possible explanation is simply that the loss of haloperidol-elicited Fos expression occurs only in one subset of dorsolateral striatal neurons. It is possible either that the remaining neurons that did mount a Fos response to haloperidol challenge are the dorsolateral striatal cells that subserve catalepsy, or simply that sufficient neurons remain that are involved in the striatal component of catalepsy to effect the behavioral response. Alternatively, other parts of the striatum or other (downstream) components of extended corticostriatofugal systems may be more critically involved in catalepsy.

Conventional APDs such as haloperidol effectively reduce positive psychotic symptoms and secondary negative symptoms, and also have some beneficial effects on cognition, albeit not to the same degree in most cognitive tasks as clozapine and other atypical APDs (56). The degree to which NT is involved in these therapeutic aspects of haloperidol is unclear, particularly in the caudate-putamen. Although the decrease in concentrations of NT in cerebrospinal fluid of persons with schizophrenia is thought to be associated with negative symptoms (18), primary negative symptoms are thought to reflect cortical rather than dorsal striatal dysfunction (57). NTR-1 and D2 receptors are expressed in some layer V pyramidal cells in the cortex (47, ¶). Because these cortical projection neurons are glutamatergic, it is possible that the loss of NT in NT knockout mice may alter glutamatergic regulation of striatal function, and thus be manifested as a change in striatal function, including certain forms of learning. Given the context dependence of the activity of striatal neurons (58), future studies will need to specifically examine different cognitive tasks in NT knockout mice to relate such changes to APD action, particularly in view of the differences in various APDs in their actions, both positive and negative, on cognition in persons with schizophrenia.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. En Li and the Massachusetts General Hospital Gene Targeting Core Facility for invaluable assistance in blastocyst injection and generation of chimeric mice. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL 33307 (to P.R.D.) and MH 57995 (to A.Y.D.), a pilot project grant from the University of Massachusetts Medical School Genetics Program, and the National Parkinson Foundation Center of Excellence at Vanderbilt University.

Abbreviations

- APD

antipsychotic drug

- EPS

extrapyramidal motor side effects

- NT

neurotensin

- ES

embryonic stem

- NTR

neurotensin receptor

- NT/N gene

neurotensin/neuromedin N gene

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. AF348489).

Wang, H. & Pickel, V. M. (2000) Soc. Neurosci. Abstr. 26, 531.1.

References

- 1.Deutch A Y, Moghaddam B, Innis R B, Krystal J H, Aghajanian G K, Bunney B S, Charney D S. Schizophr Res. 1991;4:121–156. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(91)90030-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meltzer H Y, Deutch A Y. In: Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. Seigel G J, Agranoff B W, Albers R W, Fisher S K, Ehler M D, editors. New York: Lippincott-Raven; 1999. pp. 1053–1072. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Creese I, Burt D R, Snyder S H. Science. 1976;192:481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seeman P. Synapse. 1987;1:133–152. doi: 10.1002/syn.890010203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y, Gil R, Kegeles L S, Weiss R, Cooper T B, Mann J J, Van Heertum R L, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deutch A Y, Lee M C, Iadorola M J. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1992;3:332–341. doi: 10.1016/1044-7431(92)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson G S, Fibiger H C. Neuroscience. 1992;46:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen T V, Kosofsky B E, Birnbaum R, Cohen B M, Hyman S E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4270–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deutch A Y. In: Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology: Antipsychotics. Csernansky J, editor. Berlin: Springer; 1996. pp. 117–161. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merchant K M, Dobner P R, Dorsa D M. J Neurosci. 1992;12:652–663. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-02-00652.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merchant K M, Dorsa D M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3447–3451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nyberg S, Nakashima Y, Nordstrom A L, Halldin C, Farde L. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1996;29:40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merchant K M. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1994;5:336–344. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1994.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robertson G S, Tetzlaff W, Bedard A, St.-Jean M, Wigle N. Neuroscience. 1995;67:325–344. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00049-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shearman L P, Weaver D R. Mol Brain Res. 1997;47:275–285. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nemeroff C B. Biol Psychiatry. 1980;15:283–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinkead B, Binder E B, Nemeroff C B. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:340–351. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Garver D L, Bissette G, Yao J K, Nemeroff C B. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:484–488. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma R P, Janicak P G, Bissette G, Nemeroff C B. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1019–1021. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.7.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vincent J P, Mazella J, Kitabgi P. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:302–309. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01357-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le F, Cusack B, Richelson E. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:1–3. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)81561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vita N, Oury-Donat F, Chalon P, Guillemot M, Kaghad M, Bachy A, Thurneyssen O, Garcia S, Poinot-Chazel C, Casellas P, et al. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;360:265–272. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(98)00678-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dobner P R, Barber D L, Villa-Komaroff L, McKiernan C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3516–3520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.10.3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mercer E H, Hoyle G W, Kapur R P, Brinster R L, Palmiter R D. Neuron. 1991;7:703–716. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tybulewicz V L J, Crawford C E, Jackson P K, Bronson R T, Mulligan R C. Cell. 1991;65:1153–1163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90011-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li E, Bestor T H, Jaenisch R. Cell. 1992;69:915–926. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90611-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bannon M J, Lee J-M, Giraud P, Young A, Affolter H-U, Bonner T I. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:6640–6642. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howells R D, Kilpatrick D L, Bhatt R, Monahan J J, Poonian M, Udenfriend S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:7651–7655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grima B, Lamouroux A, Blanot F, Biguet N F, Mallet J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:617–621. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carraway R, Leeman S E. J Biol Chem. 1976;251:7035–7044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carraway R E, Mitra S P. Regul Pept. 1987;18:139–154. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(87)90003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffman D C, Donovan H. Psychopharmacology (Berlin) 1995;120:128–133. doi: 10.1007/BF02246184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snijders R, Kramacy N R, Hurd R W, Nemeroff C B, Dunn A J. Neuropharmacology. 1982;21:465–468. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(82)90032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams F G, Murtaugh M P, Beitz A J. Mol Brain Res. 1990;7:347–358. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(90)90084-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Merchant K M, Miller M A, Ashleigh E A, Dorsa D M. Brain Res. 1991;540:311–314. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90526-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fadel J, Dobner P R, Deutch A Y. Neurosci Lett. 2001;303:17–20. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01708-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zahm D S. Neuroscience. 1992;46:335–350. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(92)90056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Senger B, Brog J S, Zahm D S. Neuroscience. 1993;57:649–660. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bean A J, During M J, Deutch A Y, Roth R H. J Neurosci. 1989;9:4430–4438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-12-04430.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deutch A Y, Zahm D S. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1992;668:232–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb27353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brog J S, Zahm D S. Neuroscience. 1995;65:71–86. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00460-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brog J S, Zahm D S. Neuroscience. 1996;74:805–812. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merchant K M, Hanson G R, Dorsa D M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:806–812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dragunow M, Robertson G S, Faull R L M, Robertson H A, Jansen K. Neuroscience. 1990;37:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90399-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boegman R J, Vincent S R. Synapse. 1996;22:70–77. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199601)22:1<70::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leveque J C, Macias W, Rajadhyaksha A, Carlson R R, Barczak A, Kang S, Li X M, Coyle J T, Huganir R L, Heckers S, Konradi C. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4011–4020. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04011.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boudin H, Pélaprat D, Rostène W, Beaudet A. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:76–89. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960909)373:1<76::AID-CNE7>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alexander M J, Leeman S E. J Comp Neurol. 1998;402:475–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferraro L, Tanganelli S, O'Connor W T, Bianchi C, Ungerstedt U, Fuxe K. Synapse. 1995;20:362–364. doi: 10.1002/syn.890200409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ferraro L, Antonelli T, O'Connor W T, Fuxe K, Soubrie P, Tanganelli S. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6977–6989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-17-06977.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wagstaff J D, Gibb J W, Hanson G R. Brain Res. 1997;748:241–244. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radke J M, Owens M J, Ritchie J C, Nemeroff C B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11462–11464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindstrom L H, Widerlov E, Bissette G, Nemeroff C. Schizophr Res. 1988;1:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(88)90040-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breslin N A, Suddath R L, Bissette G, Nemeroff C B, Lowrimore P, Weinberger D R. Schizophr Res. 1994;12:35–41. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chartoff E H, Ward R P, Dorsa D M. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meltzer H Y, McGurk S R. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25:233–255. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deutch A Y. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55, Suppl. B:37–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Graybiel A M. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 1998;70:119–136. doi: 10.1006/nlme.1998.3843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]