Abstract

Background

Self-assessment is an intricate component of continuing professional development and lifelong learning for health professionals. The agreement between self and external assessment for cognitive tasks in health professionals is reported to be poor; however, this topic has not been reviewed for technical tasks in surgery.

Objective

To compare self and external assessment for technical tasks in surgery.

Methods

MEDLINE, ERIC, and Google Scholar databases were searched for data from January 1960 to November 2011. Inclusion criteria were restricted to articles published in English in peer-reviewed journals, which reported on a comparison between self and external assessment for a technical task in a surgical specialty and involved medical students, surgical residents, surgical fellows, or practicing surgeons. Abstracts of identified articles were reviewed and pertinent full-text versions were retrieved. Manual searching of bibliographies for additional studies was performed. Data were extracted in a systematic manner.

Results

From a total of 49 citations, 17 studies (35%) were selected for review. Eight of the 17 studies (47%) reported no agreement, whereas 9 studies (53%) reported an agreement between self and external assessment for technical tasks in surgery. Four studies (24%) reported higher self versus external assessment scores, whereas 3 studies (18%) reported lower self versus external assessment scores. Sixteen studies (94%) focused on retrospective self-assessment and 1 study (6%) focused on predictive self-assessment. Agreement improved with higher levels of participant training; with high-quality, timely, and relevant feedback; and with postprocedure video review.

Conclusions

This review demonstrated mixed results regarding an agreement between self and external assessment scores for technical tasks in surgery. Future investigations should attempt to improve the study design by accounting for differences between men and women, conducting paired and independent mean comparisons of self and external assessments, and ensuring that external assessments are valid and reliable.

Introduction

Health professionals are expected to participate in lifelong learning and professional development.1 Accurate assessment of an individual's limitations in knowledge, attitudes, and practice is an essential requirement not only for appropriate professional development and lifelong learning2 but also for maintaining self-regulation in the health professions.3 Consequently, the topic of self-assessment is current and relevant to health professions education.

The construct of self-assessment has been defined in a number of ways. Some authors define self-assessment as a process that is initiated and driven by the individual and is used for ongoing self-improvement.4 Others define it as a mechanism for identifying one's strengths and weaknesses.5 Eva and Regehr4 suggest that the construct of self-assessment should be defined in terms of reflection (a conscious and deliberate reinvestment of mental energy aimed at exploring and elaborating one's understanding of the problem), self-monitoring (a moment-to-moment assessment and awareness of a given situation), and self-directed assessment seeking (a pedagogic activity of looking for external assessments of one's current level of performance).

The construct of self-assessment has been broken down into 3 domains: predictive, retrospective, and concurrent.6 Predictive self-assessment is described as the ability to predict one's performance on a future competency-based assessment; retrospective self-assessment is described as the ability to rate one's performance in a recently completed exercise; and concurrent self-assessment is described as the ability to self-identify one's current learning needs.6

To answer the question of whether health professionals are accurate in self-assessment, several authors have summarized the literature on the accuracy of self versus observed measures of competence as pertaining to cognitive tasks (diagnostic ability, identification of learning needs, etc) and have found self-assessment to be inaccurate.3,6,7 Potential proposed causes of poor accuracy in self-assessment for cognitive tasks include flawed experimental methodology,7 regression effects,8 impression management,9 gender effects,10 and differences in participants' skill levels.6 Regression to the mean is the tendency of extreme groups (very low or very high performers) to regress toward the overall mean when assessed for the second time. Albanese and colleagues8 postulated that inaccurate self-assessments of performance by the extreme groups may be, in part, because of regression effects. The skill level of the health professional also has a significant effect on the accuracy of self-assessment, with less-competent individuals more likely to overestimate their true performance, whereas more competent individuals tend to underestimate their performance.11

Although most prior reviews on the topic of self-assessment have focused on the comparison of self versus external assessment for cognitive tasks, this topic has yet, to our knowledge, to be reviewed for technical tasks.3,6,7,12 Eva and Regehr4 suggest that self-assessment of a cognitive task may be fundamentally different from an objective technical task. This is based on the notion that performance on a technical task, unlike a cognitive task, can be judged through immediate feedback provided by the outcome of that task.11 Thus, the finding of poor agreement between self and external assessment for cognitive tasks may not hold true for technical tasks. The purpose of this review was to compare self versus external assessment as pertaining to technical tasks in surgery.

Methods

Search Strategy

MEDLINE (US National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC; Computer Sciences Corporation, Falls Church, VA, under contract with the Institute of Education Sciences, Washington, DC), and Google Scholar (Google Inc, Mountain View, CA) databases were searched for data from January 1960 to November 2011 with the following MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) terms and key words: self-assessment, self-monitoring, self-rating, self-evaluation, clinical competence, reflective practice, surgery, general surgery, psychometrics, reliability, validity, educational measurement, adult education, higher education, and postsecondary education. Bibliography lists of relevant studies were searched manually for additional studies not captured by the original search strategy.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal, reported on a comparison between self and external assessment for a technical task in a surgical specialty, and involved medical students, surgical residents, surgical fellows, or practicing surgeons. Studies were excluded if they did not compare self and external assessment or if a comparison was made for a nontechnical task, such as communication, teamwork, professionalism, and similar assessments.

Data Extraction

The following information was extracted from each study: study population, study location, nature of the technical task, method of self and external assessment, domain of self-assessment (retrospective, predictive, or concurrent), type of statistical analysis, and study outcomes.

Results

Search Results

The search strategy yielded 49 citations (figure). After applying the inclusion criteria, 23 articles (47%) were selected for a full-text review. Following a full-text review, 2 additional articles were included from a manual bibliographic search, and 8 of the 23 articles (35%) were excluded because they did not focus on self-assessment of a technical task or did not compare self to external assessment. A total of 17 articles were included in this review.

Flow Diagram Showing Selection and Screening Process for Eligible Studies

Domains of Self-Assessment

The construct of self-assessment was divided into 3 domains: retrospective, predictive, and concurrent. Sixteen studies (94%) focused on retrospective self-assessments and asked participants to evaluate their performance after completion of a technical task.9,13–27 One study (6%) focused on predictive self-assessment and asked participants to predict their future performance on a technical task.28

Methods for Self and External Assessment

Self-assessments were conducted using checklists (4/17; 24%),9,16,17,26 global rating scales (14/17; 82%),9,13,14,16–19,21–27 estimated times to task completion (1/17; 6%),28 estimated numbers of errors (1/17; 6%),28 and hierarchical task analysis (1/17; 6%). Five studies (24%) used more than one method of self-assessment,9,16,17,26,28 and 1 study (6%) did not report its method.15 External assessments were conducted using checklists (5/17; 29%),9,16,17,25,26 global rating scales (14/17; 82%),9,13,14,16–19,21–27 pass-fail scores (1/17; 6%),25 estimated times to task completion (1/17; 6%),28 estimated numbers of errors (1/17; 6%),28 and hierarchical task analysis (1/17; 6%). One study (6%) using 3 methods,25 and 1 study (6%) did not specify the method for external assessment.15

Modes of External Assessment

Fifteen studies (88%) used faculty or experts in the field9,13–19,21–27; 1 study (6%) used a peer group,17 1 study (6%) used computer-generated scores,28 and 1 study (6%) used a trained external observer as a mode of external assessment.20

Statistical Methods to Compare Self and External Assessment

Statistical approaches to the comparisons of self and external assessments were quite heterogeneous. Nine studies (53%) used correlation coefficients,14–19,23,26,27 3 studies (18%) used analysis of variance,9,22,28 3 studies (18%) used paired t tests,15,21,24 1 study (6%) used Mann-Whitney U tests,13 1 study (6%) used κ coefficients,20 1 study (6%) did not report the methods of comparison used.25

Comparison of Self Versus External Assessment

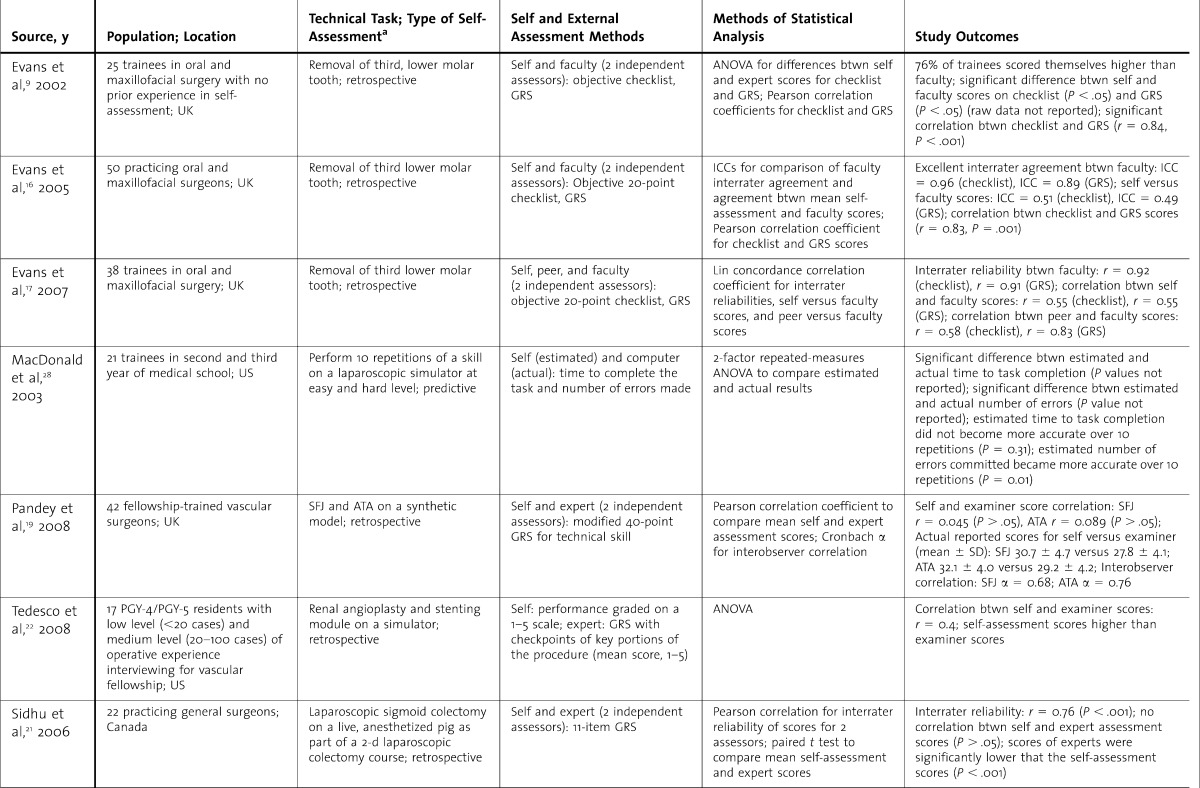

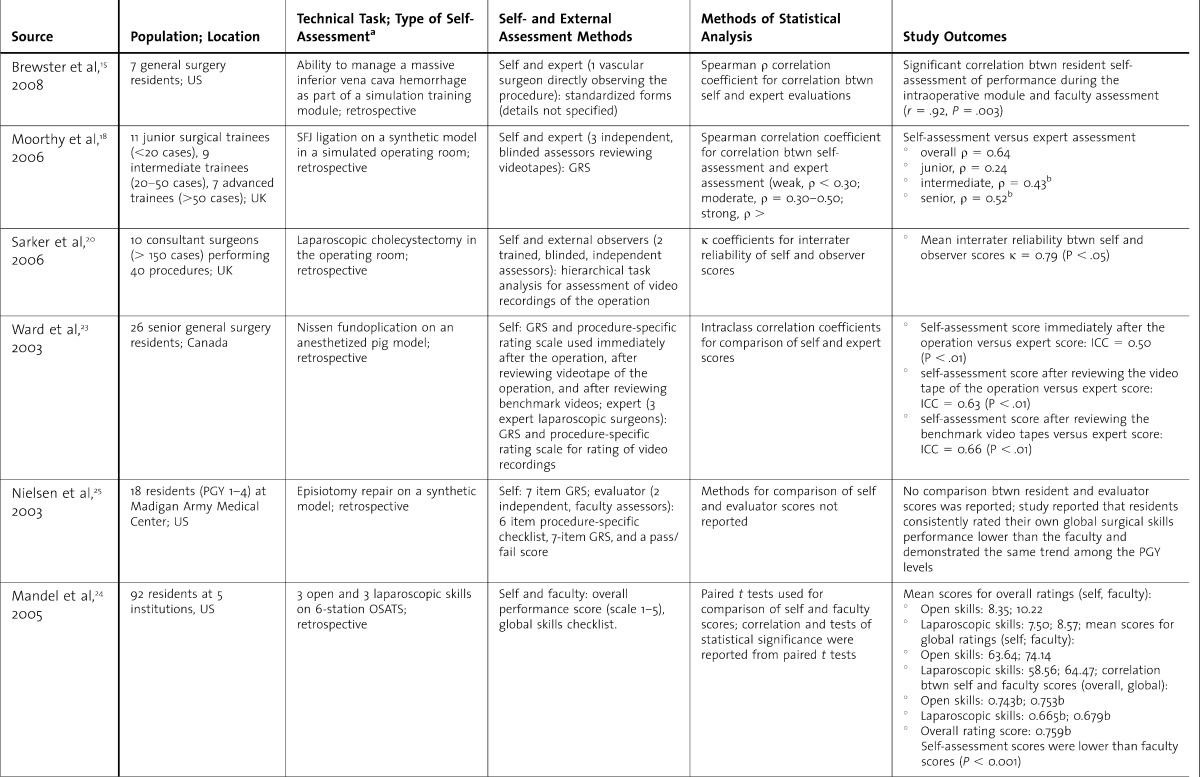

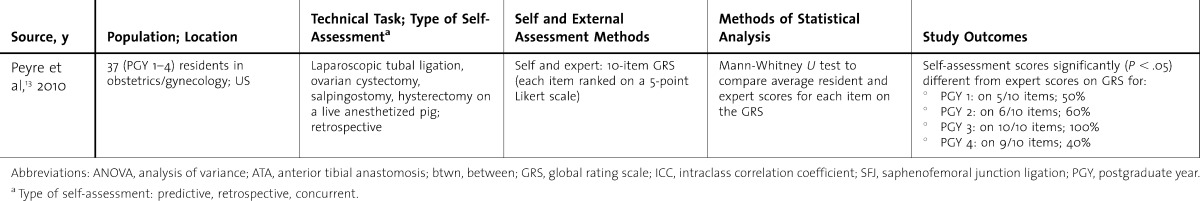

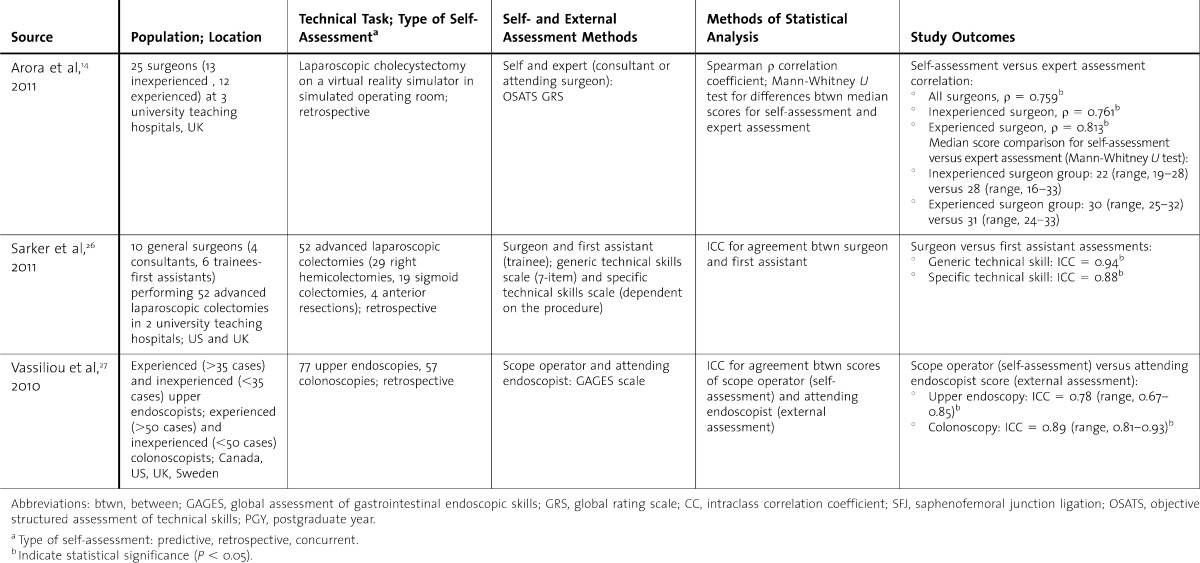

Eight studies (47%) did not report an agreement between self and external assessment (table 1),9,13,16,17,19,21,22,28 whereas 9 studies (53%) reported an agreement between self and external assessment (table 2).14,15,18,20,23–27 Of the 8 studies that did not find agreement, 4 (50%) reported higher self versus external assessment scores,17,19,21,22 and 3 studies (34%) reported lower self versus external assessment scores.14,24,25 For studies that compared means of self and external assessment scores, self-assessment scores were higher in studies that did not report an agreement between self and external assessment,17,19,21,22 and lower for studies that did report an agreement.14,24,25 Multiple external assessors were used in 5 of 8 studies (63%) that did not report an agreement between self and external assessments,9,16,17,19,21 and in 4 of 9 studies (44%) that did report an agreement.18,20,23,25

TABLE 1.

Summary of Studies That Did Not Report an Agreement Between Self-Assessment and External Assessment for Technical Tasks in Surgery

TABLE 2.

Summary of Studies That Did Report an Agreement Between Self-Assessment and External Assessment for Technical Tasks in Surgery

TABLE 1.

Continued.

TABLE 2.

Continued.

Influence of Sex of Participants and Level of Training

One out of 17 studies (6%) explored the influence of the sex of participants on self-assessment scores.16 Level of training was accounted for in 3 out of 8 studies (38%) that did not report an agreement between self and external assessment,13,22,28 and in 5 out of 9 studies (56%) where the researchers found agreement.14,18,23,25,27

Discussion

Eight studies (47%) reported a lack of agreement between self and external assessment,9,13,16,17,19,21,22,28 whereas 9 studies (53%) reported agreement.14,15,18,20,23–27 It is thus not possible to make a definitive conclusion regarding the agreement between self and external assessment scores for technical tasks in surgery. The mixed results of this review are in agreement with prior reviews of self-assessment in health3,6 and nonhealth professions.11,12 Reasons for the mixed findings of this review can be classified into methodologic factors and human factors.

Methodologic Factors

Nine studies in this review (53%) used a correlational study design. This design has a number of limitations, including the possible lack of validity and reliability of the external “gold standard,” the problem of the differential use of the assessment scale and group-level analysis.7 One of the main assumptions of a correlation study design is that external “gold standard” assessment is valid and reliable.7 This, however, is often not the case. Most studies (15/17; 88%) in this review used faculty or expert assessments as the “gold standard” to which self-assessment scores were compared. The reliability12,29,30 and validity7 claims for expert scores have been found suspect by a number of studies. Consequently, a comparison against a nonreliable and nonvalid external assessment measure is expected to be inherently flawed.

The problem of the differential use of the assessment scale and group-level analysis stems from another assumption of the correlational study design—the appropriateness to consider a group of individual self-assessment scores as a set of coherent scores.7 This assumption fails if study participants use the assessment scale inconsistently (some using the top end and others using the bottom end of the scale) or if they do not evaluate the same aspects of their performance. Correlational study design can be improved with the use of multiple external assessors to improve reliability, and with the provision of explicit behavioral anchors for the assessment scale to ensure appropriate use of the scale.7

Another methodologic issue that is prevalent in studies of self versus external assessment is the failure to account for potential moderating variables, including participant's sex and level of training. In a meta-analysis of studies examining self-assessment in medical students, Blanch-Hartigan10 reported that female students tended to underestimate their performance in comparison to male students. In this review, the agreement between self and external assessment increased with an increasing level of experience of the self-assessor. This finding is in agreement with the results of other studies in medicine11 and higher education.12

Human Factors

Human factors may have also contributed to the mixed results of this review. These factors include self-deception,16 impression management,16 and cognitive and social factors.4 The effect of self-deception, defined as the lack of insight into one's incompetence,16 and impression management, defined as “faking good” or pretending to be better than one is, on self versus external assessment scores has been examined by Evans and colleagues.16 Impression management was postulated to be the reason for higher self versus external assessment scores as trainees tried to represent themselves in the best possible light.16,28 Impression management may have been in part responsible for the findings of no agreement and higher self versus external assessment scores (table 1). One can hypothesize that as a trainee becomes more experienced, the tendency for impression management decreases, and self-assessment scores become more comparable to the external assessment scores.

The effects of cognitive and social factors may also provide some insight into the mixed findings of this review. Cognitive factors are said to include information neglect and memory bias,4 both of which lead to poor recall of personal failures from the past. From a sociobiologic perspective, information neglect has a protective effect because an optimistic outlook on life can prevent depression and apathy.4 Social factors have been described as the lack of adequate feedback from peers and supervisors.4 In the 7 retrospective self-assessment studies (41%), information neglect and memory biases may have influenced individuals' self-assessment scores, thereby leading to no agreement between self and external assessment scores.9,13,16,17,19,21,22

Suggestions to Improve the Agreement Between Self Versus External Assessment

Strategies to improve the agreement between self versus external assessment include external feedback (high-quality, timely, coherent, and nonthreatening), video-based reviews, and external benchmarks of performance.5,18,19,21,23,31,32 All of these approaches function as “reality checks” for the participant to prevent potential information neglect and memory biases,33 whereas absent or flawed external feedback may reinforce self-deception.31 Self-assessment of technical tasks in surgery should involve peers, faculty, and other external sources of information.5 In a study by Ward et al,23 a significant improvement in the agreement between self and external assessment for a Nissen fundoplication in an anaesthetized pig model was noted for trainees who reviewed their performance on videotape.

Conclusion

This review compared self versus external assessment for technical tasks in surgery and found mixed results. In general, agreement between self and external assessment was seen to improve with higher levels of expertise; high-quality, timely, and relevant feedback; and postprocedure video review. Future investigations should focus on improving study designs by accounting for differences between sexes, by conducting paired and independent mean comparisons between self and external assessments, and by ensuring that external assessments are valid and reliable.

Footnotes

Boris Zevin, MD, is Senior Surgical Resident and PhD Candidate at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Funding: Dr Zevin is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship.

References

- 1.Lipsett PA, Harris I, Downing S, Lipsett PA, Harris I, Downing S. Resident self-other assessor agreement: influence of assessor, competency, and performance level. Arch Surg. 2011;146(8):901–906. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. http://www.royalcollege.ca/portal/page/portal/rc/members/cpd/cpd_accreditation/self_assessment_programs. Accessed September 26, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon MJ. A review of the validity and accuracy of self-assessments in health professions training. Acad Med. 1991;66(12):762–769. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199112000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eva KW, Regehr G. “I'll never play professional football” and other fallacies of self-assessment. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(1):14–19. doi: 10.1002/chp.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eva KW, Regehr G. Self-assessment in the health professions: a reformulation and research agenda. Acad Med. 2005;80(10 Suppl):S46–54. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200510001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094–1102. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ward M, Gruppen L, Regehr G. Measuring self-assessment: current state of the art. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2002;7(1):63–80. doi: 10.1023/a:1014585522084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albanese M, Dottl S, Mejicano G, Zakowski L, Seibert C, Van Eyck S, et al. Distorted perceptions of competence and incompetence are more than regression effects. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2006;11(3):267–278. doi: 10.1007/s10459-005-2400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evans AW, Leeson RMA, Newton-John TRO. The influence of self-deception and impression management on surgeons' self-assessment scores. Med Educ. 2002;36(11):1095. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.134612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanch-Hartigan D. Medical students' self-assessment of performance: results from three meta-analyses. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;84(1):3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77(6):1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Falchikov N, Boud D. Student self-assessment in higher education: a meta-analysis. Rev Educ Res. 1989;59(4):395–430. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peyre SE, MacDonald H, Al-Marayati L, Templeman C, Muderspach LI. Resident self-assessment versus faculty assessment of laparoscopic technical skills using a global rating scale. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:37–41. doi:10.5116/ijme.4bf1.c3c1. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arora S, Miskovic D, Hull L, Moorthy K, Aggarwal R, Johannsson H, et al. Self versus expert assessment of technical and non-technical skills in high fidelity simulation. Am J Surg. 2011;202(4):500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brewster LP, Risucci DA, Joehl RJ, Littooy FN, Temeck BK, Blair PG, et al. Comparison of resident self-assessments with trained faculty and standardized patient assessments of clinical and technical skills in a structured educational module. Am J Surg. 2008;195(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans AW, Leeson RMA, Newton John TRO, Petrie A. The influence of self-deception and impression management upon self-assessment in oral surgery. Br Dent J. 2005;198(12):765–769; discussion 755. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans AW, Leeson RMA, Petrie A. Reliability of peer and self-assessment scores compared with trainers' scores following third molar surgery. Med Educ. 2007;41(9):866–872. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02819.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moorthy K, Munz Y, Adams S, Pandey V, Darzi A. Imperial College–St. Mary's Hospital Simulation Group. Self-assessment of performance among surgical trainees during simulated procedures in a simulated operating theater. Am J Surg. 2006;192(1):114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pandey VA, Wolfe JH, Black SA, Cairols M, Liapis CD, Bergqvist D. European Board of Vascular Surgery. Self-assessment of technical skill in surgery: the need for expert feedback. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90(4):286–290. doi: 10.1308/003588408X286008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarker SK, Hutchinson R, Chang A, Vincent C, Darzi AW. Self-appraisal hierarchical task analysis of laparoscopic surgery performed by expert surgeons. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(4):636–640. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0312-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sidhu RS, Vikis E, Cheifetz R, Phang T. Self-assessment during a 2-day laparoscopic colectomy course: can surgeons judge how well they are learning new skills. Am J Surg. 2006;191(5):677–681. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tedesco MM, Pak JJ, Harris EJ, Jr, Krummel TM, Dalman RL, Lee JT. Simulation-based endovascular skills assessment: the future of credentialing. J Vasc Surg. 2008;47(5):1008–1001; discussion 1014. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward M, MacRae H, Schlachta C, Mamazza J, Poulin E, Reznick R. Resident self-assessment of operative performance. Am J Surg. 2003;185(6):521–524. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(03)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mandel LS, Goff BA, Lentz GM. Self-assessment of resident surgical skills: is it feasible. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(5):1817–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.07.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen PE, Foglia LM, Mandel LS, Chow GE. Objective structured assessment of technical skills for episiotomy repair. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(5):1257–1260. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00812-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sarker SK, Delaney C. Feasibility of self-appraisal in assessing operative performance in advanced laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2011;13(7):805–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vassiliou MC, Kaneva PA, Poulose BK, Dunkin BJ, Marks JM, Sadik R, et al. Global Assessment of Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Skills (GAGES): a valid measurement tool for technical skills in flexible endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):1834–1841. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0882-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald J, Williams RG, Rogers DA. Self-assessment in simulation-based surgical skills training. Am J Surg. 2003;185(4):319–322. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Regehr G, Hodges B, Tiberius R, Lofchy J. Measuring self-assessment skills: an innovative relative ranking model. Acad Med. 1996;71(10)(suppl):S52–S54. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199610000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin D, Regehr G, Hodges B, McNaughton N. Using videotaped benchmarks to improve the self-assessment ability of family practice residents. Acad Med. 1998;73(11):1201–1206. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199811000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epstein RM, Siegel DJ, Silberman J. Self-monitoring in clinical practice: a challenge for medical educators. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(1):5–13. doi: 10.1002/chp.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans AW, McKenna C, Oliver M. Trainees' perspectives on the assessment and self-assessment of surgical skills. Assess Eval High Educ. 2005;30(2):163–174. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Galbraith RM, Hawkins RE, Holmboe ES. Making self-assessment more effective. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(1):20–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]