Abstract

Current research provides few suggestions for modifications to functional analysis procedures to accommodate low rate, high intensity problem behavior. This study examined the results of the extended duration functional analysis procedures of Kahng, Abt, and Schonbachler (2001) with six children admitted to an inpatient hospital for the treatment of severe problem behavior. Results of initial functional analyses (Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982/1994) were inconclusive for all children because of low levels of responding. The altered functional analyses, which changed multiple variables including the duration of the functional analysis (i.e., 6 or 7 hrs), yielded clear behavioral functions for all six participants. These results add additional support for the utility of an altered analysis of low rate, high intensity problem behavior when standard functional analyses do not yield differentiated results.

Keywords: functional analysis, low-rate problem behavior

The development of a functional analysis of problem behavior (Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1982/1994) transformed the treatment process for self-injurious behavior (SIB) and other problem behaviors by allowing clinicians and researchers to systematically identify the determinants of problem behavior. This functional analysis technology minimized the trial and error approach to treatment selection by allowing the clinician to predict which interventions were more likely to be effective (i.e., those directly designed to address the function of the problem behavior; Iwata, Pace, Cowdery, & Miltenberger, 1994). This approach has become widely considered standard practice in the treatment of severe problem behaviors (Hanley, Iwata, & McCord, 2003).

Since its development, functional analysis technology has advanced in numerous ways to accommodate specific challenges. It has been used to assess various forms of aberrant behavior including aggression (e.g., Mace, Page, Ivancic, & O'Brien, 1986), property destruction (e.g., Fisher, Lindaur, Alterson, & Thompson, 1998), pica (e.g., Mace & Knight, 1986), elopement (e.g., Piazza et al., 1997), sexual behavior (e.g., Fyffe, Kahng, Fittro, & Russell, 2004), rumination (e.g., Wilder, Register, Register, Bajagic, & Neidert, 2009), and noncompliance (e.g., Wilder, Harris, Reagan, & Rasey, 2007). Functional analyses have been used for aberrant behavior with populations other than those with intellectual disabilities (ID), including children with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; Northup et al., 1995), typically developing children (e.g., Wilder et al., 2007), and individuals with emotional disorders (e.g., DePaepe, Shores, Jack, & Denny, 1996). Researchers have adapted the functional analysis for use in numerous settings including outpatient clinics (e.g., Northup et al., 1991), schools (e.g., Bloom, Iwata, Fritz, Roscoe, & Carreau, 2011; Mace & West, 1986), and homes (e.g., Day, Horner, & O'Neill 1994; Ellingson et al., 2000).

Although generally effective in identifying the reinforcers that maintain behavior, there are some conditions under which a functional analysis may be less likely to reveal a behavioral function. One such condition is when the individual emits a low rate of problem behavior either in the naturalistic context or in the functional analysis. For example, Derby et al. (1992) examined the results of 79 functional analyses. They failed to identify a behavioral function in 29 of those cases because the target behavior rarely occurred. Similarly, Asmus et al. (2004) were unable to identify the maintaining reinforcer in 14 of their 152 functional analyses for similar reasons.

Low rates of behavior during the functional analysis may be a result of several factors. It is possible that the discriminative stimuli or the specific reinforcers for the problem behavior are not present in the setting in which the functional analysis is conducted Alternatively, the individual may have limited exposure to the reinforcement contingencies in the functional analysis context. In each situation, additional analyses or modifications are warranted and several have been examined in an effort to identify the determinants of problem behavior (Hanley et al., 2003; Iwata, 1994).

Several researchers have focused on altering the standard functional analysis protocol by modifying the discriminative stimuli and potential reinforcers for test conditions. For example, condition modifications have included differential access to tangible items (e.g., Day, Rea, Schussler, Larsen, & Johnson, 1988; Mace & West, 1986), an interrupted activity (e.g., Adelinis & Hagopian, 1999; Fisher, Adelinis, Thompson, Worsdell, & Zarcone, 1998), or diverted attention (e.g., Mace et al., 1986) contingent upon problem behavior. In these instances, an additional stimulus and/or motivating operation (MO) is present (e.g., another person chatting with the potential source of attention, presence of a highly preferred but unavailable item) and the consequence may also differ from a standard functional analysis test condition. Each of these modifications has proven fruitful in identifying the function of problem behavior.

For individuals whose behavior occurs at low rates with high intensity, modifications may not yield clear outcomes even when the behaviors seem to be evoked and maintained by the same variables manipulated in a standard functional analysis.

For individuals whose behavior occurs at low rates with high intensity, modifications such as the ones described above may not yield clear outcomes even when the behaviors seem to be evoked and maintained by the same variables manipulated in a standard functional analysis. Perhaps the behavior occurs so infrequently during the functional analysis sessions that the individual has limited opportunities to contact reinforcement. Additionally, the session duration may not be sufficient to allow MOs to affect the behavior. In these situations, it may be helpful to observe the effects of the contingencies over an extended period of time (Hanley et al., 2003).

Wallace and Iwata (1999) examined the effects of differing session durations on functional analysis outcomes. They obtained functional analysis data sets based on 15-min sessions for 46 individuals. They then generated additional data sets by removing the last 5 min and 10 min of each session (creating 10- and 5-min sessions, respectively). Behavior analysis graduate students trained in functional analysis interpreted the data using visual inspection. When comparing the 15-min and 10-min data sets, no variations were reported in identified behavioral function; whereas, when comparing the 15-min and 5-min data sets, variations were reported for three data sets. Similarly, Rolider (2007) found that extended session length (i.e., 10 to 30 min) resulted in differentiated responding for 3 of 7 participants. These data suggest that, in some cases, longer session duration may result in differential levels of responding.

Kahng et al. (2001) evaluated the use of a modified functional analysis (MFA), which incorporated an extended duration functional analysis of aggression following a standard functional analysis that was inconclusive due to low rates of behavior. The modified functional analysis was similar to Iwata et al. (1982/1994) except for a increased session duration from 10 min to 7 hr (9 a.m. to 4 p.m.) and necessitating that only one session was conducted per day. Aggression occurred only on days in which the social attention condition was conducted, suggesting that problem behavior was maintained by social positive reinforcement in the form of access to attention. Kahng et al. (2001) demonstrated that increasing the duration of exposure to environmental variables hypothesized to be MOs clarified the function of problem behavior and led to an effective function-based intervention. However, Kahng et al. only examined the MFA with one participant. The purpose of the current study was to replicate the procedures of Kahng et al. with multiple participants who engaged in low rate, high intensity problem behavior.

Methods

Participants and Setting

Our search through our archival records identified 10 individuals admitted to a hospital for the assessment and treatment of severe problem behavior for whom an MFA was conducted over the past 10 years. The findings from the six individuals for whom the MFA showed clear differential responding across test conditions are included in this manuscript to illustrate the use of the extended duration functional analysis procedure. Bobby was a 10-year-old male diagnosed with fragile X syndrome, ID, and autism. He was admitted for assessment and treatment of severe aggression, disruption, and SIB. Darius was a 17-yearold male diagnosed with ID, autism, and cerebral palsy. He was admitted for the assessment and treatment of severe aggression and disruption. Paul was a 16-year-old male diagnosed with ID, autism, mood disorder-not otherwise specified (NOS), disruptive behavior disorder-NOS, and stereotypic movement disorder with SIB. He was admitted for the assessment and treatment of severe aggression, disruption, and SIB. Jack was an 11-year-old male diagnosed with ID, autism, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and mood disorder. He was admitted for the assessment and treatment of severe SIB, aggression, and disruptive behaviors. Mickey was a 19-year-old male diagnosed with ID and autism. He was admitted for the assessment and treatment of severe SIB, aggression, and disruptive behaviors. Finally, Jane was a 14-year-old female diagnosed with ID, autism, and disruptive behavior disorder-NOS. She was admitted for the assessment and treatment of severe SIB, aggression, and disruptive behaviors. Prior to their admissions, these individuals' behavior caused injuries to themselves such as cuts to arms from smashing glass (Bobby) and severe hematomas (Jack). Additionally, they caused injuries to others such as severe hematomas (Bobby, Darius, Paul, Jack, and Mickey) and a broken arm (Darius), concussions (Jane) as well as pinched nerves and open wounds from biting and stabbing others with a pencil (Darius, Paul, Mickey, and Jane, respectively).

The standard functional analysis1 (SFA) was conducted in a padded session room (3 m x 3 m) or in a bedroom (Jack only). The SFA environment allowed programming and control for the presence of all stimuli and people. Session materials included preferred and less preferred toys (as determined by a preference assessment), academic and daily living tasks, chairs and a table, and busy materials (e.g., magazine) for the experimenter. The MFA was conducted in the main open living area of the inpatient unit. This environment was less controlled and participants shared the space with other patients and staff. Session materials included those materials from the SFA in addition to furniture and stimuli typically found in a living area (e.g., sofas, televisions). One to eight sessions were conducted daily, 3 to 5 days per week.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Frequency data were collected using either laptop computers with data captured in 10-s intervals (SFA) or using a paper and pen with data captured in 30-min intervals (MFA). Aggressions were defined as hitting with an open or closed fist, kicking, throwing objects within 2 ft of a person, scratching, hair pulling, stomping or jumping on feet, biting, pinching, grabbing, forcefully grabbing/pulling on others' clothes or extremities, or pushing. Disruptions were defined as throwing objects that landed farther than 2 ft from a person, swiping objects, kicking, hitting, throwing the body into objects or hard surfaces (e.g., walls, furniture, windows, and floor), overturning furniture, ripping, tearing, or breaking objects. We defined SIB as hitting any part of the body (open or closed hand), banging any part of the head on a hard surface (e.g., walls, furniture, windows, mirror, and floor), biting any part of the body, hair-pulling, and self-scratching (Bobby and Paul only). Direct care staff or behavior analysts trained in data collection procedures and familiar with the individuals' target behaviors served as observers. The minimum requirement for the direct care staff was a high school degree or GED with some experience working with individuals with ID. The minimum educational requirements for the behavior analysts were a bachelor's degree with extensive experience working with individuals with ID.

Interobserver agreement was calculated within 10-s (SFA) or 30-min intervals (MFA) by dividing the smaller number of responses by the larger number within an interval, averaging these scores across the total number of intervals within a session, and multiplying by 100%. If both observers agreed that behavior did not occur during an interval, it was scored as an agreement. Two observers independently, but simultaneously, collected data during 38%, 26%, 56%, 29%, 44%, and 48% of SFA sessions for Bobby, Darius, Paul, Jack, Mickey, and Jane, respectively. Interobserver agreement averaged 99.5 % (range 83–100%), 100%, 99.5% (range 90–100%), 99% (range 95– 100%), 95% (range 94–95%), and 99.9% (range 98–100%) during the SFA for Bobby, Darius, Paul, Jack, Mickey, and Jane, respectively. During the MFA, a second observer collected data during 48%, 81%, 49%, 47%, and 6% of 30-min intervals for Bobby, Paul, Jack, Mickey, and Jane respectively. A second observer was rarely available to collect data for Jane, and was not available to collect data during Darius' MFA. The agreement coefficients averaged 97% (range 79–100%), 98% (range 86–100%), 80% (range 57–100%), 94% (range 83–100%), and 99.5% (range 98–100%) for Bobby, Paul, Jack, Mickey, and Jane respectively.

Procedures

Standard functional analysis.

An SFA was conducted with all six individuals using procedures described by Iwata et al. (1982/1994). Initial sessions were 10 or 15 min in duration and were later extended to 20 (Bobby, Paul, and Jane), 30 (Darius), or 40 min (Mickey). Experimental conditions were randomly ordered (Bobby, Darius, and Paul) and consisted of demand, attention, alone, and toy play as a control condition. For Jack and Mickey, the sequence of experimental conditions was presented in a fixed sequence consisting of ignore or alone, attention (standard or divided), toy play, and demand. Jane's experimental conditions were also conducted in a fixed sequence of alone, attention, toy play, demand, and tangible. In addition to Jane, a tangible condition was included in Bobby and Paul's SFAs. Consequences were provided for SIB (Bobby, Paul, Mickey, and Jane), aggression (all individuals), and disruption (Bobby, Darius, Paul, Mickey, and Jane). Behavior analysts conducted all of these sessions.

During the demand condition, the experimenter presented activities of daily living and/or academic demands using a graduated prompting system (verbal, gestural, and full physical prompts). Demands were chosen from the participant's individualized education plan. Contingent upon problem behavior during the demand sequence, the experimenter said, “Okay, you don't have to,” and removed the demand materials for 30 s. Compliance resulted in a brief statement of praise and presentation of the next demand. The purpose of this condition was to test for problem behavior maintained by social negative reinforcement in the form of escape from demands.

During the attention condition, the experimenter pretended to be busily engaged in an activity while the individual had access to moderately preferred toys. The experimenter delivered a brief verbal reprimand (e.g., “Don't do that!” “That hurts me”) contingent on the occurrence of problem behavior. All appropriate requests for attention were ignored. The purpose of this condition was to test for behavior maintained by social positive reinforcement in the form of gaining access to adult attention.

During the divided attention condition, the individual had access to moderately preferred toys while two experimenters engaged in a conversation with each other. The experimenter stopped conversation, oriented toward the individual, and delivered a brief verbal reprimand (e.g., “Don't do that!” “That hurts me”) contingent upon the occurrence of problem behavior. All appropriate requests for attention were ignored. The purpose of this condition was to test for behavior maintained by social positive reinforcement in the form of gaining access to adult attention.

During the alone condition, the individual was alone in a room without access to toys or attention. In some cases, the alone condition was replaced with an ignore condition for safety. Specifically, an ignore condition was conducted to protect participants from excessive tissue damage due to SIB. During the ignore condition, the individual was in a room without access to toys or attention. An experimenter was present in order to block instances of SIB; safety criteria were developed on an individual basis. No other forms of attention or eye contact were provided at any time. The purpose of these conditions was to test for behavior maintained by automatic reinforcement.

During the tangible condition, the individual had 2-min access to preferred toys or 30-s access to food items (Jane only) before the start of the session. At the start of session, the experimenter removed the toys/edibles from the individual and stated, “You cannot play with these any longer” or “You cannot have any more food right now.” Contingent on the occurrence of problem behavior, the experimenter said, “Okay,” and returned the toys for 30 s or delivered a small amount of an edible. The experimenter ignored appropriate requests for toys and edibles. The purpose of this condition was to test for sensitivity of problem behavior to social positive reinforcement, in the form of access to preferred items.

During the toy play condition, the individual had access to highly preferred toys and experimenter attention on a fixed time (FT) 30-s schedule. Appropriate requests for attention were honored throughout the session. The experimenter did not provide any specific response for problem behavior (i.e., continued with the FT schedule of attention). This condition served as a control to which all other conditions were compared.

Modified functional analysis.

The procedures of the MFA were similar to those of Kahng et al. (2001). Sessions were 6 to 7 hrs in duration and conducted between the hours of 9 a.m. and 4 p.m.; data were adjusted for meals and bathroom visits because programmed consequences were not in place during these times. One MFA condition was conducted each day, Monday through Friday. All of the individual's programmed activities were temporarily suspended (e.g., speech appointments, academics, circle time). Experimental conditions were randomly ordered across days and consisted of demand (except for Jack), attention, toy play, and tangible (Paul and Jane only) (see Table 1 for details). Due to the time intensive nature of this analysis, not all experimental conditions from the SFA were included. The control condition and the conditions thought to be most likely to impact problem behavior based on caregiver report and behavior analyst's observations were included in the MFA. The direct care staff and behavior analysts conducted this analysis.

Table 1.

Procedural Variations Across the Standard (SFA) and Modified Functional Analysis (MFA).

The demand condition of the MFA was similar to that of the SFA except that demands were presented continuously for 45–50 min work periods throughout the day interspersed with breaks (i.e., a much longer duration of the same consistent and relatively high rate of demands). Contingent on problem behavior, the experimenter said, “Okay,” and the demand materials were removed for 30 s. Brief praise was delivered contingent on compliance with the task. Following the demand period, the individual received a 10–15 min break in which minimal attention was provided. During this break, there were no programmed social consequences for problem behavior. This cycle repeated throughout the day and was interrupted only for essential activities (e.g., bathroom, meals, and nurses' visits).

During the MFA attention condition, the experimenter engaged in busy-like activities (e.g., reading magazines) for the entire day. That is, the experimenter remained within 3–5 ft of the participant but remained socially unavailable. The individual had access to one or two moderately preferred toys. Staff members not directly working with the individual were instructed not to provide any form of attention and to ignore attempts for attention (e.g., waving, smiling, and eye contact). Only essential demands were delivered (e.g., brush your teeth, get your lunch) and minimal attention was provided for successful completion of the task. Contingent upon the occurrence of problem behavior, the experimenter provided a brief reprimand (e.g., “Don't do that!” “That hurts me!”).

During the MFA divided attention condition, two experimenters engaged in conversation with each other for the entire day but not directly with Jane or Mickey. The experimenter remained within 3–5 ft of the participant at all times but remained socially unavailable. The individual had access to one or two moderately preferred toys. Staff members not directly working with Jane or Mickey were instructed to not provide any form of attention and to ignore attempts for attention (e.g., waving, smiling, and eye contact). Only essential demands were delivered (e.g., brush your teeth, get your lunch), and minimal attention was provided for successful completion of the task. Contingent upon the occurrence of problem behavior, one experimenter stopped conversation, oriented toward the individual, and provided a brief reprimand (e.g., “Don't do that!” or “That hurts me!”).

The MFA tangible condition was similar to the tangible condition of the SFA; however, the individual had access to the preferred toys once an hour for 15 min. The only modification to this procedure was for Jane, who only received access to the item for 15 minutes at the start of the session/day instead of once an hour. There were no programmed consequences for problem behavior during times when the individual had access to the preferred items. Once the 15 min elapsed, the experimenter removed the toys and stated, “You cannot play with these any longer.” Contingent on the occurrence of problem behavior during the remaining 45 mins of the hr or remainder of the day (Jane only), the experimenter said, “Okay, you can play with this” and the toys were returned for 30 s or 2 min (Jane only). The toys remained in sight, just out of reach. Only essential demands were delivered (e.g., brush your teeth, get your lunch) throughout the day. Appropriate requests for the toys were ignored, and the experimenter provided attention once every minute.

During the toy play condition, the individual had access to highly preferred toys and experimenter attention throughout the day. In addition, all reasonable requests were honored (e.g., taking a walk, having a drink). Only essential demands were delivered (e.g., brush your teeth) throughout the day. This condition served as the control comparison for all other conditions.

For both analyses, the experimenter terminated the sessions if redness, swelling, or bruising occurred, and a physician or nurse examined the injuries. Sessions continued until visual inspection revealed clear differentiation between one or more conditions and the control condition or until low rates of problem behavior were observed across consecutive cycles as determined by the experimenter using visual inspection. Please see Table 1 for a detailed comparison of variables across the two functional analyses for each participant. Following the completion of this study, effective behavioral interventions were developed for each participant but are not reported here.

Results

For all participants, the SFA is reported as responses per min (RPM) whereas the MFA is reported as responses per hour (RPH). The results of Bobby's functional analyses are depicted in Figure 1. During the SFA (top panel) low and variable rates of problem behavior were observed across all conditions. When the MFA was initiated, high rates of problem behavior were initially observed across all conditions. Problem behavior decreased in the attention and toy play conditions after three sessions but persisted in the demand condition (M = 100 RPH). The results of the MFA suggested that Bobby's problem behavior was maintained by social negative reinforcement in the form of escape from academic demands.

Figure 1.

Responses per min of SIB, aggression, and disruption for Bobby in the Standard Functional Analysis (top panel); responses per hour of SIB, aggression, and disruption in the Modified Functional Analysis (bottom panel).

The results of the functional analyses for Darius are depicted in Figure 2. Problem behavior was not observed for 10 consecutive series of the SFA conditions (33 sessions total; top panel). Although it occurred at a low rate (M = 0.7 RPH), problem behavior was observed exclusively in the attention condition during the MFA (bottom panel). These data suggest that Darius' problem behavior was maintained by social positive reinforcement in the form of adult attention.

Figure 2.

Responses per min of aggression and disruption for Darius in the Standard Functional Analysis (top panel); responses per hour of aggression and disruption in the Modified Functional Analysis (bottom panel).

Paul's functional analyses are presented in Figure 3. Problem behavior rarely occurred during the SFA (M = .01 RPM). Upon the initiation of the MFA, problem behavior occurred in the demand condition (M = 16.2 RPH) exclusively, suggesting that Paul's problem behavior was maintained by social negative reinforcement in the form of escape from academic and chore demands.

Figure 3.

Responses per min of SIB, aggression, and disruption for Paul in the Standard Functional Analysis (top panel); responses per hour of SIB, aggression, and disruption in the Modified Functional Analysis (bottom panel).

Jack's functional analyses are depicted in Figure 4. Low and variable rates of aggression were observed across conditions during the SFA (M = .06 RPM). In the MFA, problem behavior occurred at higher rates in the attention condition relative to the toy play condition (M = 8.3 RPH), suggesting that Jack's problem behavior was maintained by social positive reinforcement in the form of access to attention.

Figure 4.

Aggressive responses per min for Jack in the Standard Functional Analysis (top panel); Aggressive responses per hour in the Modified Functional Analysis (bottom panel).

Mickey's functional analysis results are presented in Figure 5. Although problem behavior did occur during the SFA (top panel), rates were low, variable, and undifferentiated (M = .57 RPM). Mickey's problem behavior was initially variable in both the toy play and demand conditions of the MFA. Beginning with session 6, we had Mickey move from area to area every hour to better replicate his typical school routine. After this change, problem behavior increased during the demand condition (M = 41 RPH) relative to the toy play condition. These results suggested that Mickey emitted problem behavior to escape demands.

Figure 5.

Responses per min of SIB, aggression, and disruption for Mickey in the Standard Functional Analysis (top panel); Responses per hour of SIB, aggression, and disruption in the Modified Functional Analysis (bottom panel).

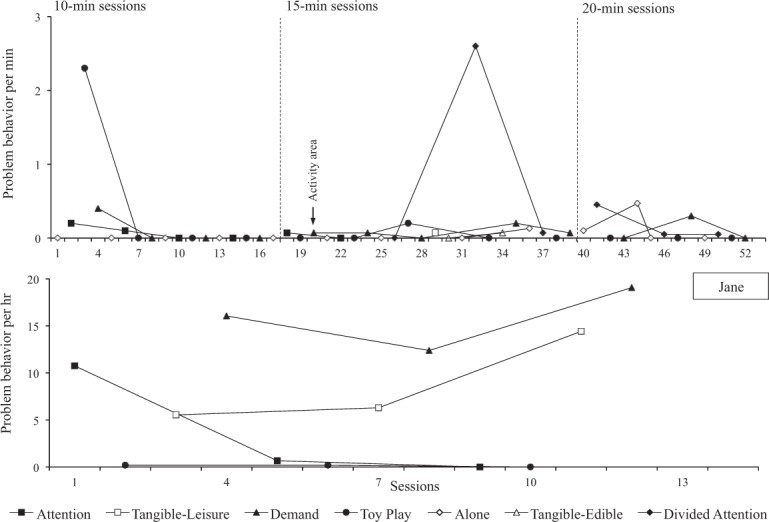

The results of Jane's functional analyses are displayed in Figure 6. Low rates of problem behavior were observed across conditions during the SFA (M = .2 RPM). By contrast, responding eventually differentiated across conditions during the MFA. These results indicated that Jane engaged in problem behavior for social negative reinforcement in the form of escape from academic demands (M = 15.8 RPH), as well as social positive reinforcement in the form of access to tangible items (M = 8.8 RPH).

Figure 6.

Responses per min of SIB, aggression, and disruption for Jane in the Standard Functional Analyses (top panel); responses per hour of SIB, aggression, and disruption in the Modified Functional Analysis (bottom panel).

Discussion and Recommendations for Practitioners

When high intensity problem behavior occurs at very low rates either prior to or during a functional analysis, clinicians have typically had to rely upon indirect assessment methods to inform intervention planning (e.g., Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007; Sturmey, 1995). Kahng et al. (2001) introduced the method of extending the duration of functional analysis conditions and conducting the analysis under more natural conditions in to attempt to detect function. The current study provides additional evidence that an MFA can be used to assess the functions of high-intensity, low-rate problem behavior when initial functional analyses prove inconclusive.

The initial SFA of severe problem behavior for six individuals with ID and ASD yielded inconclusive results due to low rates of problem behavior. Once modifications were made (see Table 1) and the duration of the functional analysis sessions was increased from brief periods (i.e., 10 to 40 mins) to a large portion of the day (i.e., 6 to 7 hrs), the analyses yielded clear behavioral functions for all 6 participants presented here, though it did not detect the function of problem behavior for 4 others. More specifically, problem behavior occurred at consistently higher rates in test conditions relative to the control for the participants described in the current study. For the participants whose data were not included, problem behavior remained either undifferentiated or did not occur.

For the six individuals for whom clarity was achieved with the MFA, problem behavior occurred so infrequently or sporadically during the SFA that it was impossible to isolate the reinforcing contingencies. Although there were several variations of functional analyses for different participants, the consequences (e.g., escape, attention, access to tangibles) remained constant for all participants across both analysis types. These individuals were exposed to the putative MOs for a longer duration in the MFA and encountered a greater number of instances of the putative reinforcer for their problem behavior. Therefore, it is possible that the relevant MO to evoke problem behavior was absent during the initial SFA sessions, and that the increased exposure to the antecedent variations (e.g., longer duration) may have been sufficient to allow MOs to affect the behavior (Smith, Iwata, Goh, & Shore, 1995). Alternatively, it may have been the case that the longer session duration permitted the participant to more readily contact the reinforcement contingencies.

It should be noted that multiple other variables were modified from the SFA to the MFA (e.g., experimenter, setting, session duration, number of test conditions) making it difficult to determine exactly which variable(s) may have resulted in greater clarity during the MFA (see Table 1). For example, incorporation of the naturalistic setting (i.e., general living area of the hospital unit) might have been the single critical determinant of increased clarity; however, problem behavior occurred at very low rates in that setting during times when the experimental sessions were not being conducted. This pattern suggests that the setting itself was probably not the single critical variable that produced differentiation in the MFA. Although it is possible that one of the other modifications may be partially responsible for the increased clarity of results, the increased session duration is the only variable that had not been directly explored in one or more prior analyses with each participant.

One limitation to this study may have been the sequence of the functional analyses. That is, the SFA always preceded the MFA. For clinical purposes, there was no justification for immediately starting a much more intensive MFA prior to conducting a SFA. However, from an experimental standpoint, prior exposure to reinforcement contingencies during the SFA may have resulted in differential responding during the MFA.

It is important to note that the MFA may require skill sets beyond those typically demonstrated by direct care staff. That is, trained behavior analysts are best suited to conducting and overseeing functional analyses of severe and dangerous problem behavior. However, Iwata et al. (2000) trained undergraduate students with minimal behavior analytic training to assist in conducting specific conditions of functional analyses of SIB. The MFA in our study was conducted by a combination of individuals with extensive training in behavior analysis who oversaw the work of direct care staff with minimal backgrounds in behavior analysis. Practitioners should recognize that although direct care staff with a minimal behavior analytic training conducted the MFA, these staff did not interpret data or make decisions regarding behavioral function. Master's or doctoral level behavior analysts oversaw the implementation of this analysis at all times. Therefore, when given the proper training, it may be possible for individuals with a limited background in behavior analysis and functional analysis methodology to conduct the MFA (e.g., Wallace, Doney, Mintz-Resudek, & Tarbox, 2004).

The amount of resources necessary to conduct an MFA may be one of the greatest barriers to adoption. Each participant in the current study had at least 1:1 supervision for the duration of the study for purposes of data collection and experimenter involvement. This challenge of the availability of resources may be reflected in the absence of any interobserver agreement data for Darius and lower levels of sessions with a secondary observer for Jack and Jane. This level of resource allocation may not be feasible for all practitioners, who instead may opt to use assessment methods that are obviously (e.g., indirect assessment only) or at least apparently (e.g., descriptive analyses) less arduous. However, given the sporadic nature of low rate behavior, these alternative assessments are unlikely to reveal a behavioral function for low rate behavior. Research generally suggests that results of descriptive analyses and indirect assessments are not sufficient to identify behavioral function (e.g., Lerman & Iwata, 1993; Mace & Lalli, 1991). Practitioners should consider that the MFA may actually be easier to implement in a naturalistic setting (e.g., school) than the SFA because the analysis can be conducted amidst daily activity. Future research should replicate and extend these procedures in less intensive settings to demonstrate the assessment's utility.

Finally, practitioners should take care when exposing individuals to long periods of deprivation during the course of the MFA. Differentiated rates of problem behavior were obtained only after session duration was increased; therefore, the long periods of deprivation were necessary in these cases because the results of the assessments were used to guide treatment development. However, it may be possible that similar results could have been identified with shorter sessions (e.g., 4 hrs).

Despite these limitations, in the event that an SFA fails to effectively isolate the reinforcing contingencies of low rate, high intensity problem behavior, an MFA may be warranted. Alterations to the functional analysis can focus on manipulating the consequences for the problem behavior and/or the antecedents (Hagopian, Rooker, Jessel, & DeLeon, in press). Although both types of manipulations may be effective in helping to elucidate the behavioral function, shorter duration sessions may not allow the problem behavior to contact any modified consequences. Therefore, the advantage of focusing on antecedent manipulations for low rate behaviors may be that it provides a longer exposure to the MOs that affect problem behaviors.

Before practitioners conduct an MFA, multiple factors should be considered to determine the appropriateness of conducting an MFA in their environment. First, consider if it is reasonable to manipulate MOs. For example, it may not be appropriate to limit access to attention in all environments. Second, determine if it is appropriate to implement consequences for problem behavior across the day. For example, it might not be appropriate to deliver escape for problem behavior in a classroom full of other students. Third, assess the social validity of MFA procedures with individuals who will be responsible for its implementation. In other words, directly ask the paraprofessional whether he or she will feel comfortable withholding attention throughout the day. Finally, consider whether adequate person resources are available to ensure staff and client safety and procedural integrity throughout each condition.

Practitioners should also evaluate the necessity of conducting an MFA at such an extended duration. In most cases of low level responding during functional analyses, clear behavioral function can be determined through shorter duration extensions (e.g., 30-min, 1-hr sessions). Practitioners need to consider (a) how quickly a treatment needs to be developed and (b) how disruptive the problem behavior is in order to determine how many extensions to attempt prior to conducting an MFA. In those cases in which these shorter duration functional analyses fail to identify function, an MFA should be considered.

It is important to note that we used the MFA when the participant exhibited low rates of problem behaviors during our analyses. Another type of unclear pattern of undifferentiated responding would be those functional analyses in which the individual exhibits problem behaviors but at variable and undifferentiated levels. In these cases, it may be that the individual is unable to discriminate the contingencies across conditions when brief sessions of different conditions are rapidly alternated in a multielement design. Therefore, in these instances, practitioners should consider moving to a pairwise design (Iwata, Duncan, Zarcone, Lerman, & Shore, 1994) prior to increasing the duration of sessions.

Finally, practitioners should plan ahead for how treatments will be systematically evaluated following the MFA. Treatments should be assessed in a similar fashion as the MFA; that is, treatment procedures should be evaluated for extended periods of time (i.e., all day). Practitioners may consider evaluating a comprehensive treatment package initially in order to immediately reduce problem behavior. A component analysis of the individual elements of the treatment can then be conducted to ensure the treatment is the most basic and manageable intervention that will produce beneficial effects.

Footnotes

We would like to thank David Russell, Katharine Gutshall, Kelly Townley, Nicole Hausman, Deeannah Taylor, and Meghan Deshais with their assistance in conducting this study. Eric W. Boelter is now at Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Health, Seattle Children's.

Action Editor: Linda LeBlanc

1For the purposes of this study, we refer to the shorter, 10-, 15-, 20-, or 40-min functional analysis as the “standard functional analysis.”

References

- Adelinis J. D, Hagopian L. P. The use of symmetrical “do” and “don't” requests to interrupt ongoing activities. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:519–523. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmus J. M, Ringdahl J. E, Sellers J. A, Call N. A, Andelman M. S, Wacker D. P. Use of a short-term inpatient model to evaluate aberrant behavior: Outcome data summaries from 1996 to 2001. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:283–304. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom S. E, Iwata B. A, Fritz J. N, Roscoe E. M, Carreau A. B. Classroom application of a trial-based functional analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2011;44:19–31. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2011.44-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J. O, Heron T. E, Heward W. L. Applied behavior analysis. New Jersey: Pearson, Merrill, Prentice Hall; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Day H. M, Horner R. H, O'Neill R. E. Multiple functions of problem behaviors: Assessment and intervention. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:279–289. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day R. M, Rea J. A, Schussler N. G, Larsen S. E, Johnson W. L. A functionally based approach to the treatment of self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1988;12:565–589. doi: 10.1177/01454455880124005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePaepe P. A, Shores R. E, Jack S. L, Denny R. K. Effects of task difficulty on the disruptive and on-task behavior of students with severe behavior disorders. Behavioral Disorders. 1996;21:216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Derby K. M, Wacker D. P, Sasso G, Steege M, Northup J, Cigrand K, Asmus J. Brief functional assessment techniques to evaluate aberrant behavior in an outpatient setting: A summary of 79 cases. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1992;25:713–721. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1992.25-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellingson S. A, Miltenberger R. G, Stricker J. M, Garlinghouse M. A, Roberts J, Galensky T. L. Analysis and treatment of finger sucking. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:41–52. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W. W, Adelinis J. D, Thompson R. H, Worsdell A. S, Zarcone J. R. Functional analysis and treatment of destructive behavior maintained by termination of “don't” (and symmetrical “do”) requests. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:339–356. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher W. W, Lindauer S. E, Alterson C. J, Thompson R. H. Assessment and treatment of destructive behavior maintained by stereotypic object manipulation. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1998;31:513–527. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1998.31-513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyffe C. E, Kahng S, Fittro E, Russell D. Functional analysis and treatment of inappropriate sexual behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:401–404. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagopian L. P, Rooker G. W, Jessel J, DeLeon I. G. Clarification of undifferentiated functional analysis outcomes. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hanley G. P, Iwata B. A, McCord B. F. Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2003;36:147–185. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2003.36-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B. A. Functional analysis methodology: Some closing comments. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:413–418. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B. A, Dorsey M. F, Slifer K. J, Bauman K. E, Richman G. S. Toward a functional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:197–209. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-197. (Reprinted from Analysis and Intervention in Developmental Disabilities, 2, 3–20, 1982) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B. A, Duncan B. A, Zarcone J. R, Lerman D. C, Shore B. A. A sequential, test-control methodology for conducting functional analyses of self-injurious behavior. Behavior Modification. 1994;18:289–306. doi: 10.1177/01454455940183003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B. A, Pace G. M, Cowdery G. E, Miltenberger R. G. What makes extinction work: An analysis of procedural form and function. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1994;27:131–144. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1994.27-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata B. A, Wallace M. D, Kahng S, Lindberg J. S, Roscoe E. M, Conners J, Worsdell A. S. Skill acquisition in the implementation of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:181–194. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahng S, Abt K. A, Schonbachler H. E. Assessment and treatment of low-rate high-intensity problem behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2001;34:225–228. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2001.34-225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerman D. C, Iwata B. A. Descriptive and experimental analyses of variables maintaining self-injurious behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1993;26:293–319. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1993.26-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace F. C, Knight D. Functional analysis and treatment of severe pica. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1986;19:411–416. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1986.19-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace F. C, Lalli J. S. Linking descriptive and experimental analyses in the treatment of bizarre speech. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:553–562. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace F. C, Page T. J, Ivancic M. T, O'Brien S. Analysis of environmental determinants of aggression and disruption in mentally retarded children. Applied Research in Mental Retardation. 1986;7:203–221. doi: 10.1016/0270-3092(86)90006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mace F. C, West B. J. Analysis of demand conditions associated with reluctant speech. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 1986;4:285–294. doi: 10.1016/0005-7916(86)90065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup J, Wacker D, Sasso G, Steege M, Cigrand K, Cook J, DeRaad A. A brief functional analysis of aggressive and alternative behavior in an outpatient setting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:509–522. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northup J, Broussard C, Jones K, George T, Vollmer T. R, Herring M. The differential effects of teacher and peer attention on the disruptive classroom behavior of three children with a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:227–228. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C. C, Hanley G. P, Bowman L. G, Ruyter J. M, Lindauer S. E, Saiontz D. M. Functional analysis and treatment of elopement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:653–672. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piazza C. C, Fisher W. W, Hanley G. P, Remick M. L, Contrucci S. A, Aitken T. L. The use of positive and negative reinforcement in the treatment of escape-maintained destructive behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1997;30:279–298. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1997.30-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolider N. Functional analysis of low-rate problem behavior. 2007. (Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida). Retrieved from http://gradworks.umi.com/32/81/3281592.html.

- Smith R. G, Iwata B. A, Goh H. L, Shore B. A. Analysis of establishing operations for self-injury maintained by escape. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1995;28:515–535. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1995.28-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmey P. Analog baselines: A critical review of the methodology. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 1995;16:269–284. doi: 10.1016/0891-4222(95)00014-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M. D, Doney J. K, Mintz-Resudek C. M, Tarbox R. S. F. Training educators to implement functional analyses. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:89–92. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace M. D, Iwata B. A. Effects of session duration on functional analysis outcomes. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1999;32:175–183. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1999.32-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D. A, Harris C, Reagan R, Rasey A. Functional analysis and treatment of noncompliance by preschool children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:173–177. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.44-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder D. A, Register M, Register S, Bajagic V, Neidert P. L. Functional analysis and treatment of rumination using fixed-time delivery of a flavor spray. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:877–882. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]