Abstract

The gram-negative bacterium Legionella dumoffii is, beside Legionella pneumophila, an etiological agent of Legionnaires’ disease, an atypical form of pneumonia. The aim of this study was to determine the antimicrobial activity of Galleria mellonella defense polypeptides against L. dumoffii. The extract of immune hemolymph, containing a mixture of defense peptides and proteins, exhibited a dose-dependent bactericidal effect on L. dumoffii. The bacterium appeared sensitive to a main component of the hemolymph extract, apolipophorin III, as well as to a defense peptide, Galleria defensin, used at the concentrations 0.4 mg/mL and 40 μg/mL, respectively. L. dumoffii cells cultured in the presence of choline were more susceptible to both defense factors analyzed. A transmission electron microscopy study of bacterial cells demonstrated that Galleria defensin and apolipophorin III induced irreversible cell wall damage and strong intracellular alterations, i.e., increased vacuolization, cytoplasm condensation and the appearance of electron-white spaces in electron micrographs. Our findings suggest that insects, such as G. mellonella, with their great diversity of antimicrobial factors, can serve as a rich source of compounds for the testing of Legionella susceptibility to defense-related peptides and proteins.

Keywords: phosphatidylcholine, Legionella, Galleria mellonella, apolipophorin III, Galleria defensin

1. Introduction

Legionellae are fastidious gram-negative bacteria found in moist natural environments as intracellular parasites of freshwater protozoa [1]. The bacteria also occur in man-made aquatic systems, which facilitate proliferation and dissemination of these bacteria by producing water-air aerosol. After transmission to humans, Legionella spp. can cause a pneumonia called Legionnaires’ disease. The majority of cases of Legionnaires’ disease are caused by Legionella pneumophila, but Legionella dumoffii is the fourth most common causative agent [2]. In humans, L. dumoffii causes even more serious and rapidly progressive types of pneumonia than that induced by other strains of Legionella[3]. Moreover, infection by L. dumoffii can contribute to other diseases, such as septic arthritis, pericarditis and prosthetic-valve endocarditis [4,5]. The ability of L. dumoffii to survive and multiply within protozoa [6,7] and in a human macrophage cell line has been described [8]. There are also suggestions that L. dumoffii can invade and proliferate in human alveolar epithelial cells [9]. To date, the mechanisms underlying the virulence and rapid progression of pneumonia due to L. dumoffii are poorly understood.

As an intracellular pathogen, Legionella spp. has evolved multiple strategies needed to overcome or evade the defense system of the host cell. For example, after being phagocytosed by mammalian macrophages or amoebae, L. pneumophila resides in a phagosome, whose ability to fuse with lysosomes is virtually restricted. One of the most important compounds of the host defense system produced to kill the invading pathogens are cationic antimicrobial peptides. Human β-defensins (hBDs), the members of the β-defensin family that display antimicrobial and immunomodulatory properties, are probably the essential defense factors of epithelial mucosa and macrophages [10]. It was demonstrated that although extracellular L. pneumophila was resistant to the cationic peptide antibiotic—polymyxin B—it was sensitive to hBD-2 and hBD-3 defensins, suggesting that these peptides are directly involved in the defense against Legionella in humans [10,11].

From among one thousand eukaryotic antimicrobial peptides characterized to date, about 200 have been described in insects. Insects have developed a very effective innate immunity system in which invading pathogens are efficiently eliminated by antimicrobial peptides. There are three main classes of cationic defense peptides in insects: (i) α-helical peptides without cysteine residues, e.g., cecropins, (ii) peptides with a structure stabilized by disulfide bridges, e.g., defensins, and (iii) peptides with overrepresentation of one amino acid, e.g., apidaecins or drosocins [12]. The structure of most of the insect defensins, similarly to their human counterparts, is stabilized by three disulfide bridges formed by six cysteine residues. However, in contrast to hBDs containing an αβββ scaffold, the insect defensins contain an αββ scaffold consisting of an α-helical domain and two anti-parallel β-strands in which the α-helix is stabilized by two disulfide bridges to one strand of the β-sheet. The insect defensins are active against various bacteria, yeasts and filamentous fungi; however, their activity towards Legionella has not been investigated [13]. Interestingly, Casteels et al. [14] presented evidence that insect proline-rich peptides, apidaecins, inhibited growth of L. pneumophila, indicating that other defense peptides, in addition to defensins, could be involved in overcoming Legionella infections.

In hemolymph of the greater wax moth Galleria mellonella larvae, an impressive set of cationic defense peptides differing in biochemical and antimicrobial properties was reported: insect defensins, cecropins, moricins, gloverins and proline-rich peptides. In addition to many cationic ones, two anionic defense peptides were characterized in this insect [15–21]. Among eight peptides isolated by us from larval hemolymph and tested against selected gram-negative bacteria (Escherichia coli D31, E. coli ATCC 25922, Salmonella Typhimurium), only cecropin d-like peptide inhibited growth of E. coli D31 [17]. Apart from antimicrobial peptides, certain hemolymph proteins, such as hydrophobic apolipophorin III (apoLp-III), an insect homologue of human apolipoprotein E (apoE), also exhibited antibacterial activity. Both proteins apoLp-III and apoE, in addition to functioning in lipid transport, play an important role in immunity. It was reported that G. mellonella apoLp-III inhibited growth of gram-negative bacteria S. Typhimurium and Klebsiella pneumoniae[22–24], whereas apoE was demonstrated to be involved in immune response against K. pneumoniae and Listeria monocytogenes, as well as protection against a lethal dose of Salmonella minnesota LPS [25–29].

It has been documented that the antimicrobial properties of cationic defense peptides are dependent on their positive charge and amphipathicity, which enable interactions with negatively charged membrane phospholipids [30,31]. Our unpublished results demonstrated that cultivation of L. dumoffii on a medium supplemented with choline led to an increase in the phosphatidylcholine (PC) content in the bacterial cell membrane. In the present study, we demonstrate evidence of anti-L. dumoffii activity of two antimicrobial components of G. mellonella hemolymph, apoLp-III and Galleria defensin. In addition, to provide more insight into the mechanism of interaction of G. mellonella polypeptides with cells of L. dumoffii, the effect of an increased PC content in the cell membrane on the effectiveness of their antibacterial action was investigated. The effects of the action of polypeptides on bacterial cells were imaged by transmission electron microscopy. The results presented suggest that the selected defense peptides and proteins of G. mellonella could be used as a template for designing novel anti-L. dumoffii agents.

2. Results

2.1. The Effect of Extracts of Immune G. mellonella Hemolymph on L. dumoffii Survival Rate

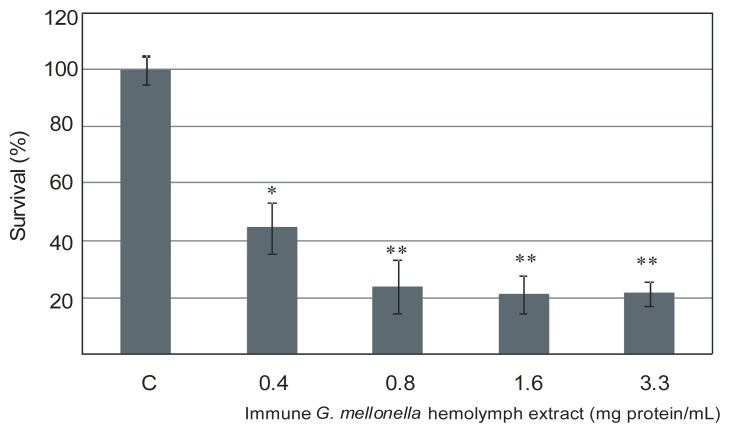

Our previous study reported that methanolic extracts of G. mellonella immune hemolymph contain an abundant hemolymph protein, apoLp-III, as a main component, and a set of defense peptides differing in biochemical and antimicrobial properties [17,32]. A preliminary study performed using a radial diffusion assay revealed inhibition of L. dumoffii growth by the G. mellonella immune hemolymph extract as a clear zone around the point of extract application (data not shown). Then, the inhibitory effect of the extract on L. dumoffii cells was examined using a colony-counting assay (Figure 1). The extract reduced the survival rate of the bacteria in a dose-dependent manner in the total protein concentration range of 0.4–0.8 mg/mL. The bacteria survivability was decreased by more than 50% at the concentration 0.4 mg/mL of the total extract protein. With the increasing concentration of the protein, the bactericidal activity of the extract was enhanced, as only 25% of the bacteria survived at the protein concentration of 0.8 mg/mL (Figure 1). However, further increasing the protein concentration to 1.6 mg/mL reduced the bacteria survival only by another 5%, whereas 3.3 mg/mL did not cause a further decrease in the bacteria survival rate, probably due to protein aggregation. The data presented were obtained after 1 h incubation of the bacteria in the presence of the hemolymph extract; however, the same bactericidal effect was observed already after 15 min of incubation of the bacteria with the extract (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Growth inhibition of L. dumoffii by G. mellonella immune hemolymph extract. The bacteria were incubated with the extract at the concentrations 0.4–3.3 mg/mL (total protein) for 1 h, as described in the Experimental Section. Next, the cells were seeded on the agar plates, and the growing colonies were counted. Survival of the untreated cells was regarded as 100% (C; control). Statistical significance: * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

2.2. The Effect of G. mellonella Defensin and apoLp-III on Survival Rate of L. dumoffii Cultured with and without Choline Supplementation

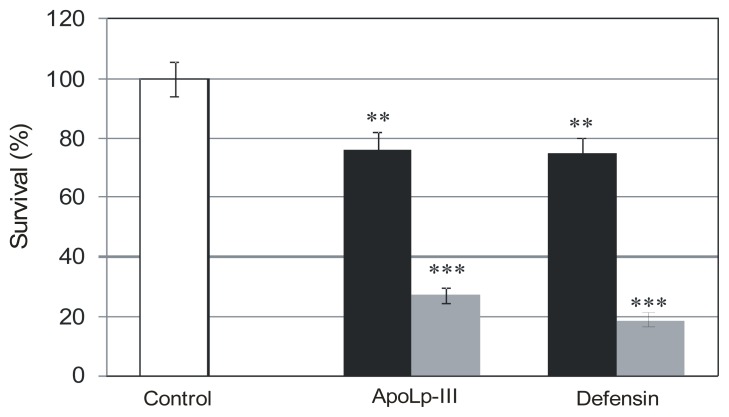

The activity of G. mellonella defensin and apoLp-III was tested against bacteria cultured on the non-supplemented, as well as choline-enriched, BCYE medium using a colony counting assay. The bacteria were incubated for 1 h in the presence of Galleria defensin in the final concentration range of 4–40 μg/mL. The effect of apoLp-III, the main component of hemolymph extract, was also evaluated at the concentration of 0.4 mg/mL. The sensitivity of L. dumoffii to both G. mellonella antimicrobial factors is presented in Figure 2. The bacteria appeared moderately sensitive to Galleria defensin (40 μg/mL), as well as apoLp-III (0.4 mg/mL). Each of the factors decreased the survival rate of L. dumoffii by ca. 30%. For concentrations below the maximal tested, Galleria defensin and apoLp-III were not effective in killing L. dumoffii (data not shown). As apoLp-III constitutes the main component of the hemolymph extract, these results could explain the need for using relatively high concentrations of the total extract protein in our experiments presented in Figure 1. Interestingly, increased sensitivity to both defense factors was observed when L. dumoffii cells were cultured in the presence of choline. As shown in Figure 2, Galleria defensin and apoLp-III were 3.8-fold and three-fold more active, respectively, against L. dumoffii in respect to bacteria grown on the non-supplemented medium.

Figure 2.

The effects of G. mellonella apoLp-III and defensin on L. dumoffii survival and influence of choline supplementation on the activity of the antimicrobial factors. The bacteria cultured on the non-supplemented (black bars) and choline-supplemented (grey bars) medium were exposed to Galleria defensin (40 μg/mL) or apoLp-III (0.4 mg/mL), as described in the Experimental Section. After seeding of the bacteria on the agar plates, the growing colonies were counted. Survival of the untreated cells was regarded as 100% (C; control). The results are given as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

2.3. Transmission Electron Microscope Observations of Legionella dumoffii

2.3.1. The Changes in the L. dumoffii Cell Morphology under the Influence of G. mellonella Immune Hemolymph Extract

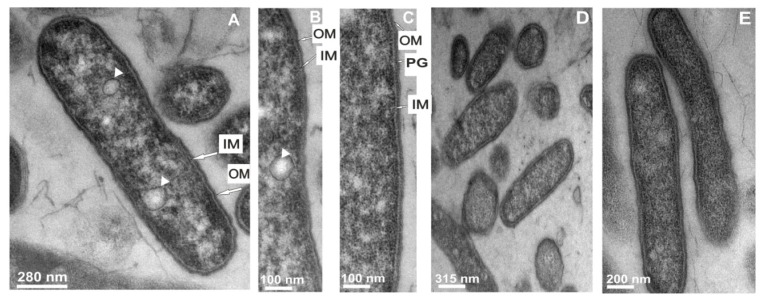

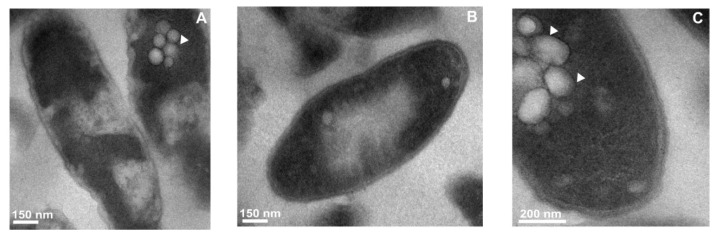

To demonstrate the direct effect of the extract of G. mellonella hemolymph on L. dumoffii cell morphology, the bacterial cells were observed by transmission electron microscopy. Microscopic observations of control cells (non-treated with the extract) revealed presence of small vacuoles, well discernible outer and inner membrane and cytoplasm containing numerous ribosomes. The cells were of longitudinal shape. The bacilli were usually 1.5 to 2.0 μm in length and 0.4 to 0.5 μm in diameter, and no infolding of the cytoplasmic membrane (“mesosomes”) was seen (Figure 3A–C). No changes in the structure were demonstrated in cell morphology of bacteria cultured on the choline-supplemented medium. All their organelles still had a typical appearance (Figure 3D,E). Microscopic examination of the bacteria treated with the extract of G. mellonella hemolymph revealed the presence of severe cell envelope damage with apparent local widening and changes in the cytoplasm appearance (Figure 3F–I). The cytoplasm was often granular and denser in comparison to the cytoplasm of the control cells. An enlarged periplasmatic space accompanying a locally widened envelope membrane was noted (Figure 3F,H). After the exposure of L. dumoffii to the G. mellonella extract, the shape of the bacteria was also modified. Additionally, loose attachment of the cell membrane was visible (arrows). The vacuoles were electron-lucent and surrounded by an electron-dense membrane (arrowheads) (Figure 3G,H). Similar changes, especially in the cell wall, were observed in bacterial cells cultured on the choline-supplemented medium after exposure to the G. mellonella extract. Distortion and loss of the cell wall in some parts of the cells were noted (Figure 3J,K).

Figure 3.

The influence of the extract of G. mellonella immune hemolymph on L. dumoffii cell morphology. The cells growing on the non-supplemented (A–C,F–I) and choline-supplemented (D,E,J–K) agar medium were exposed to G. mellonella hemolymph extract (F–I,J,K) or left untreated (A–C,D,E). Then, the cells were prepared for TEM analysis as described in the Experimental Section. (A) one big bacterium in longitudinal section; vacuoles are visible inside the cell (arrowheads); the outer and inner membrane is distinguishable in the cell envelope; (B) a fragment of the bacterium with a visible internal membrane (arrows); IM, inner membrane; OM, outer membrane; (C) a portion of the bacterium with a peptidoglycan-like layer (denoted as PG); outer and inner membranes are seen; (D,E) cells cultured on the choline-supplemented medium with a typical appearance; (F) cells showing cell wall damage and a periplasmatic space (arrows); (G) bacteria with cell wall damage (arrows) and dense cytoplasm with vacuoles (arrowhead); (H) enlarged view of a bacterium with strong cell envelope damage and cytoplasm condensation; the rest of the cells exhibit cell wall damage and presence of vacuoles (arrowhead); (I) many bacterial cells demonstrating loose attachment of the cell membrane (arrows); and (J,K) cells cultured on choline exposed to the extract with visible deterioration of the cell wall.

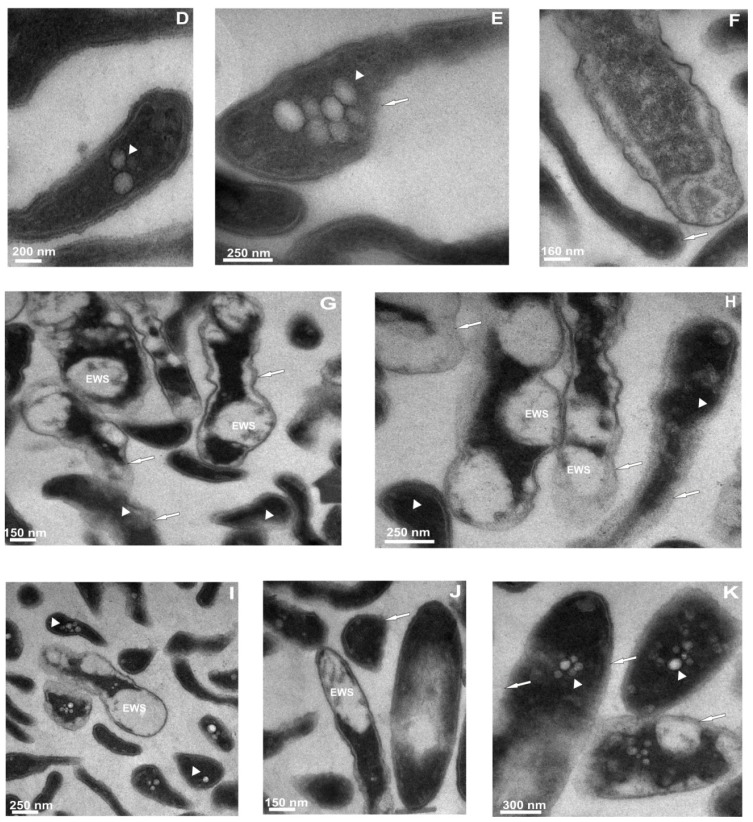

2.3.2. Ultrastructural Changes in the Cells of L. dumoffii after Treatment with Defensin and apoLp-III Isolated from G. mellonella Hemolymph

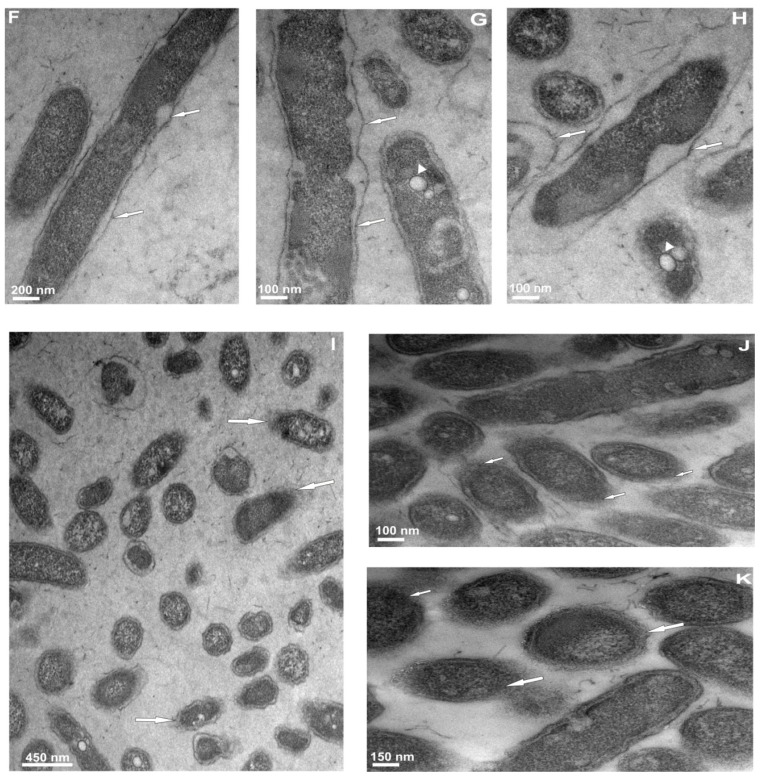

In the subsequent stage of the microscopic examination, the bacteria cultured on the non-supplemented and choline-enriched medium were treated with purified Galleria defensin or apoLp-III. The microscopic observations revealed significant changes in the ultrastructural characteristics of L. dumoffii exposed to apoLp-III, such as the presence of many vacuoles within the cytoplasm and minor changes in the cell envelope structure (Figure 4). In various parts of the cell, the cytoplasm was condensed and, additionally, regions with decreased electron density were detected (Figure 4A–C). The cells cultured on the choline-supplemented medium also revealed vacuolization of the cytoplasm after the treatment with apoLp-III. However, the cell envelope damage was greater than in the cells exposed to apoLp-III, but cultured on the medium without choline supplementation. Some cells exhibited a widened periplasmatic space (Figure 4D–F). Distinct changes were observed in the ultrastructure of cells treated with Galleria defensin and apoLp-III. Defensin treatment of L. dumoffii cells considerably affected the cell morphology of L. dumoffii, and the loss of typical subcellular organization was detected. Within the cytoplasm, large electron-white spaces (vacuole-like spaces), as well as highly condensed areas, were observed. Substantial, irreversible (lethal) cell wall damage was noticed. Some cells were shrunk, with a very dense content and barely discernible cell envelope (Figure 4G,H). The cells of bacteria cultured on the choline-enriched medium showed substantial changes due to Galleria defensin treatment. Cell shrinkage, condensation of cytoplasm and loss of cell envelope integrity were followed by the appearance of small vacuoles surrounded by an electron-dense membrane in numerous shrunken cells (Figure 4I). In cells larger in size, further destruction occurred, such as deprivation of the cell wall structure and the appearance of electron-white regions. Additionally, small vacuoles were visible in the dense cytoplasm (Figure 4J,K).

Figure 4.

The influence of defensin and apolipophorin III isolated from G. mellonella hemolymph on the ultrastructure of L. dumoffii cells. The cells grown on the non-supplemented (A–C,G,H) and choline-supplemented (D–F,I–K) medium were incubated in the presence of apoLp-III (A–F) or Galleria defensin (G–K). Then the cells were prepared for TEM analysis as described in the Experimental Section. (A,B) cells showing condensed cytoplasm, regions with decreased electron density and the presence of vacuoles (arrowhead); (C) a fragment of the bacterium with a group of visible vacuoles and dark, dense cytoplasm; (D,E) cells with vacuolization features (arrowheads) and cell envelope damage (arrow); (F) bacteria with cell wall distortion (arrow) and a widened periplasmatic space; (G) cells with electron-white spaces (EWS), membrane deterioration (arrows), and condensed content (arrowheads); (H) irreversible cell wall damage visible in bacteria (arrows) together with dense areas of cytoplasm or entire cytoplasm of the whole cells (arrowheads); (I) bacteria demonstrating loss of cell wall integrity, vacuolization of cytoplasm (arrowheads), cell shrinkage; and (J,K) cells showing cell wall damage (arrows), electron-white spaces (EWS), presence of small vacuoles (arrowheads).

3. Discussion

In the present study, the effects of G. mellonella defense peptides and proteins, essential components of insect immune response, on the viability of L. dumoffii were investigated. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the antibacterial activity of insect defense factors against this species of Legionella. L. dumoffii was found to be sensitive to Galleria defensin. The inhibitory effect of Galleria defensin on L. dumoffii is the first evidence of the antibacterial activity of this peptide. In previous studies, only the antifungal activity of Galleria defensin was reported [15,17]. Recently, G. mellonella larvae have been exploited as a model system to study L. pneumophila pathogenicity, however, susceptibility of the bacteria to G. mellonella antimicrobial proteins and peptides has not been tested [33]. Interestingly, infection of the larvae by L. pneumophila upregulated expression of Galleria defensin, suggesting involvement of this peptide in anti-Legionella response, which is consistent with our results demonstrating its anti-Legionella activity in vitro.

Antibacterial activity of G. mellonella apoLp-III against selected bacteria (Bacillus circulans, S. Typhimurium, K. pneumoniae) was reported in our previous papers [23,24]. Inhibition of L. dumoffii growth by apoLp-III is another piece of evidence for the antibacterial activity of this insect protein. Moreover, susceptibility of L. dumoffii to apoLp-III could suggest involvement of its human homologue, apoE, in anti-Legionella defense in humans.

Like other Legionella species (L. pneumophila, L. bozemanae, L. lytica), L. dumoffii utilizes extracellular choline for the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine (PC)—an important constituent of the cell envelope [34,35]. PC is primarily a component of membrane lipids in eukaryotic cells; only 15% of bacteria, mainly photosynthetic bacteria with an extensive internal membrane structure or the host cell-associated bacteria (either pathogenic or symbiotic), contain this phospholipid in their cell envelope. Aside from the role in membrane assembly, PC functions also as a modulator of a wide variety of cellular pathways. Exposure of phosphocholine groups, characteristic for bacteria residing predominantly in the respiratory tract, allows the bacteria to interact with the platelet-activating factor (PAF) receptor of the host and, consequently, to invade the epithelial cells [36].

In our experiments, the supplementation of L. dumoffii culture with choline led to the significantly increased susceptibility of the bacteria to apoLp-III and Galleria defensin. The results indicated the relationship between the increased content of the phospholipid in the bacterial cell membrane and the effectiveness of antimicrobial activity of the G. mellonella defense compounds tested. One could suggest enhanced binding of both defense factors to the cells of L. dumoffii grown in the presence of choline. Due to the fact that PC represents zwitterionic phospholipids, it seems that the interaction of Galleria defensin, as well as apoLp-III with L. dumoffii cells, was enhanced mainly by the increased hydrophobic properties of the bacterial cell envelope. Moreover, one could postulate PC to be a receptor for binding these G. mellonella defense factors to the L. dumoffii cell membrane. For example, it was reported that molecules of the synthetic antimicrobial peptide cecropin B3 containing two hydrophobic α-helical segments, clustered in the domains of the membrane enriched in lipids with neutral headgroups, such as PC [37]. It was also suggested that phosphorylcholine decorations may change the sensitivity of Haemophilus influenzae bacteria to the antimicrobial activity of the human peptide LL-37/hCAP18 [38]. Recently, it has been reported that the increase of branched-chain fatty acids and the decrease of fatty acid chain length in the L. pneumophila membrane were correlated with the increased resistance of the bacteria to warnericin RK, an amphiphilic α-helical antimicrobial peptide produced by Staphylococcus werneri[39]. Hence, sensitivity of the bacteria to antimicrobial peptides and proteins would be, at least in part, modulated by the membrane fatty acid composition.

In gram-negative bacteria, such as S. Typhimurium and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antimicrobial peptides comprise environmental signals sensed by two-component systems, PhoPQ, PmrAB and ParRS, respectively. Activation of these systems is responsible for the regulation of gene expression, leading to LPS modification and adaptive resistance to cationic antimicrobials [40–42]. In Legionella, regulation of LPS modification genes by two-component systems has not been yet reported, however a role for the PmrAB system in the regulation of several genes encoding Dot/Icm-secreted effectors has been shown recently in L. pneumophila[43]. In addition, the involvement of the rcp gene in L. pneumophila resistance to antimicrobial peptides and polymyxin B has been demonstrated [44]. Rcp protein exhibits strong sequence and functional homology to S. Typhimurium PagP protein, acting as a palmitoyl transferase able to modify the lipid A component of LPS by the addition of fatty acid palmitate. Such modification is believed to promote resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides by decreasing membrane fluidity and preventing insertion of the peptides. It is possible that Rcp protein plays a similar role in L. pneumophila[44]. Taking this into consideration, the lower susceptibility of L. dumoffii cells cultured without choline supplementation to G. mellonella defense factors reported in our study could imply sensing of the antimicrobial peptides by L. dumoffii cells and induction of expression of genes involved in the bacteria response to these molecules. Explanation of the impact of antimicrobial peptides on transcriptional regulation of the virulence factors in Legionella requires further detailed investigations. The destructive effect of the extract of G. mellonella hemolymph, apoLp-III and defensin on L. dumoffii cell morphology was observed by transmission electron microscopy. The differences between the ultrastructural changes induced by apoLp-III and by Galleria defensin are possibly related to the diverse mechanisms of action of these polypeptides against L. dumoffii. Further experimental investigations are needed to explain the mode of action of apoLp-III and Galleria defensin on the cells of L. dumoffii and the role of PC in bacterial sensitivity to these compounds.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Bacterial Strain and Culture Conditions

L. dumoffii, strain ATCC 33279 was kindly supplied by Dr. B. Fields and Dr. E. Brown from CDC Atlanta (GA, USA). The bacteria were cultured for three days at 37 °C in humid atmosphere and 5% CO2 on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar supplemented with the Growth Supplement SR110 (Oxoid, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK) [45]. For growth of bacteria on the choline-enriched medium, BCYE agar was supplied with 100 μg/mL choline chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). The bacteria collected from this medium were washed three times with water by intensive vortexing and centrifugation at 8000× g for 10 min.

4.2. Insect Culture and Immune Challenge

Larvae of the greater wax moth G. mellonella (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae) were reared on a natural diet—honeybee nest debris at 30 °C in the dark. Last instar larvae (250–300 mg in weight) were used throughout the study. For immune challenge, the larvae were pierced with a needle dipped into a pellet of viable E. coli D31 and Micrococcus luteus ATCC 10240 cells. The larvae were kept at 30 °C in the dark, and the hemolymph was collected 24 h after the treatment.

4.3. Preparation of Methanolic Extracts of G. mellonella Hemolymph

Acidic/methanolic extracts were prepared from the hemolymph of immune-challenged G. mellonella larvae. The cell-free hemolymph was diluted ten times with an extraction solution consisting of methanol:glacial acetic acid:water (90:1:9 v/v/v). Precipitated proteins were pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000× g for 30 min at 4 °C. The supernatant obtained was collected and freeze-dried, and the resulting lyophilisate was dissolved in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). For removal of lipids from the extract, the same volume of n-hexane was added, and the sample was vortexed and centrifuged at 20,000× g for 10 min at 4 °C. The upper fraction containing lipids was removed, and an equal volume of ethyl acetate was added. After vortexing and centrifugation, the water fraction was freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C until use. For the experiments, the extracts were dissolved in apyrogenic water (2/3 volume of hemolymph). The hemolymph extracts contained proteins with a molecular weight below 30 kDa (mainly apoLp-III) and defense peptides, as demonstrated in our previous paper [17].

4.4. Purification of G. mellonella Defense Peptides and Proteins

The defense peptides and proteins were purified from the methanolic extracts of the immune-challenged G. mellonella larvae hemolymph according to the modified methods described previously by Cytryńska et al. [17]. The lyophilized and deprived of lipids immune hemolymph extract was reconstituted in 0.1% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and subjected to the first step of purification using a Discovery Bio Wide Pore C18 250 mm × 4.6 mm column (Sigma) and a two buffer set: A: 0.1% TFA (v/v), B: 0.07% TFA, 80% acetonitrile (v/v). The linear 30%–70% gradient of buffer B over 35 min, 1 mL/min flow rate, and spectrophotometric detection at 220/280 nm was applied. This and all the following chromatographic steps were performed on a P680 HPLC system (Dionex, Munchen, Germany). Six consecutive fractions were collected: anionic peptide 1, lysozyme, a mixture of proline rich peptide 2 and apolipophoricin, Galleria defensin, a mixture of anionic peptide 2 and cecropin d-like peptide, as well as apolipophorin III. The fraction containing apolipophorin III was homogenous and was used without further purification. The fraction containing Galleria defensin was rechromatographed using the same column as above and the 39%–42% of buffer B over 25 min. The purity and identity of the collected fractions were confirmed by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and N-terminal sequencing. In brief, the electrophoresis was performed according to the method of Schägger and von Jagow [46], the gel obtained was electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (Immobilon PSQ, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) stained with Coomassie Brillant Blue R-250, and then the peptides were identified by Edman degradation on a Procise 491 automatic protein sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Purified Galleria defensin and apoLp-III were freeze-dried and stored at −20 °C until use. Before antimicrobial activity tests, they were dissolved in apyrogenic water.

4.5. Anti-Legionella Activity Assays

4.5.1. Radial Diffusion Assay

Ten MicroLitre (μL) of bacterial suspension adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD620) of 0.1 was placed on a BCYE agar and 5 μL of the G. mellonella hemolymph extract containing 0.125 mg of total protein, were applied centrally. After a three-day incubation of the plates at 37 °C, the bacterial growth inhibition zone, as a clear zone around the point of the extract application, was evaluated.

4.5.2. Colony Counting Assay

Ten-fold serial dilutions were made till a dilution of 10−4 from the bacterial suspension of an optical density OD620 of 0.1 corresponding to 2 × 108 cells/mL. Next, 5μL of the last dilution was transferred into sterile Eppendorf tubes and the G. mellonella hemolymph extract, purified apoLp-III or Galleria defensin to the final concentration in the range 0.4–3.3 mg/mL, 0.4 mg/mL and 4–40 μg/mL, respectively, were added. The bacteria were preincubated with the hemolymph extract or the polypeptides for 1 h at 37 °C, and then placed on the BCYE plates. After a three-day incubation at 37 °C, the grown colonies were counted. The experiments with bacteria cultured on choline-enriched medium were performed in the same way. All the experiments were conducted in three replicates. The results were referred to the controls defined as the total (100%) survival of L. dumoffii cells incubated in water without the addition of the hemolymph extract or polypeptides under the same conditions.

4.6. Preparation of Samples for Microscopic Analysis

The bacteria growing at the periphery of the clear growth inhibition zones were used for microscope observations of the effects exerted on L. dumoffii cell morphology by the G. mellonella hemolymph extract. As the control, the bacterial cells, well growing in a form of turf at a distance of 2 cm from the edge of the growth inhibition zone, were collected from the same agar plate. In order to check the influence of particular peptides, Galleria defensin or apoLp-III at the final concentration of 40 μg/mL or 0.4 mg/mL, respectively, were added to four tubes containing 50 μL of suspension of bacteria cultured on BCYE of an OD620 of 0.1 and to four tubes containing bacteria that were cultured on choline-supplemented BCYE of the same optical density. After a 1 h incubation at 37 °C, the suspensions incubated in the presence of the particular factors were pooled and centrifuged at 8000× g for 10 min. The resulting bacterial pellets were used for microscopic analyses.

4.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy Analysis of L. dumoffii Cells

The bacterial cells exposed to G. mellonella hemolymph extract were gently scraped from the agar surface using the microbiological loop and collected into the vials containing 2% formaldehyde (freshly prepared from paraformaldehyde) and 2.5% glutaraldehyde dissolved in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Then, the cell suspension was centrifuged at 8000× g for 10 min. The cell pellets were fixed for 24 h at 4 °C in buffered glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde (2.5% and 2%, respectively). After rinsing several times with 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4), the cell pellets were post-fixed in a 1% osmium tetroxide solution in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) for 2 h at 4 °C. The bacterial cells were dehydrated in a series of alcohol and acetone and embedded in LR White resin. Ultrathin sections (65 nm) were cut with a diamond knife on a microtome RMC MT-XL (Boeckeler Instruments, Tucson, AZ, USA) collected on copper grids and contrasted with the use of uranyl acetate and Reynold’s liquid. The samples were observed under a LEO-Zeiss 912 AB electron microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Oberkohen, Germany).

After incubation with the polypeptides, the bacterial pellets were flooded with the first fixative (the same as above described). The next steps of the procedure were performed as above described.

4.8. Other Methods

The concentration of protein in the hemolymph was determined using the Bradford method and bovine serum albumin as a standard [47]. The quantity of apoLp-III was determined by weight, while the concentration of defensin was measured by amino acid analysis [48].

4.9. Statistical Analysis

Each experiment was performed at least three times. The experimental values are given as means ± SD. The statistical significance of the differences between the control and test values was evaluated using Student’s t-test.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, (1) G. mellonella defense factors, defensin and apoLp-III exhibited anti-L. dumoffii activity, (2) L. dumoffii growing on choline-supplemented medium were more sensitive to defensin and apoLp-III, (3) the destructive effect of defense factors studied on bacterial cell morphology was evident in TEM images, and (4) our results indicate that insects, such as G. mellonella, with their great diversity of antimicrobial factors of different biochemical properties can serve as a rich source of compounds for testing of Legionella susceptibility to the defense-related peptides and proteins.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Barry Fields and Ellen Brown (CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA) for supplying the experimental bacteria. The authors thank Teresa Jakubowicz (Department of Immunobiology, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Lublin, Poland) and Teresa Urbanik-Sypniewska (Department of Genetics and Microbiology, Maria Curie-Sklodowska University, Lublin, Poland) for critical reading of and comments to the manuscript.

This work was supported by the grant from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education No.N N303 822640. The research was partially carried out with equipment purchased through European Union structural funds (grants POIG.02.01.00-12-064/08 and POIG.02.01.00-12-167/08).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Fields B.S., Benson R.F., Besser R.E. Legionella and Legionnaires’ disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15:506–526. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.3.506-526.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu V.L., Plouffe J.F., Pastoris M.C., Stout J.E., Schousboe M., Widmer A., Summersgill J., File T., Heath C.M., Paterson D.L., et al. Distribution of Legionella species and serogroups isolated by culture in patients with sporadic community-acquired legionellosis: An international collaborative survey. J. Infect. Dis. 2002;186:127–128. doi: 10.1086/341087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fujita I., Tsuboi H., Ohotsuka M., Sano I., Murakami Y., Akioka H., Hayashi M. Legionella dumoffii and Legionella pneumophila serogroup 5 isolated from 2 cases of fulminant pneumonia. J. Jpn. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 1989;63:801–810. doi: 10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.63.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flendrie M., Jeurissen M., Franssen M., Kwa D., Klaassen C., Vos F. Septic arthritis caused by Legionella dumoffii in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus-like disease. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011;49:746–749. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00606-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tompkins L.S., Roessler B.J., Redd S.C., Markowitz L.E., Cohen M.L. Legionella prosthetic-valve endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988;318:530–535. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198803033180902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neumeister B., Schoniger S., Faigle M., Eichner M., Dietz K. Multiplication of different Legionella species in Mono Mac 6 cells and in Acantamoeba castellanii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:1219–1224. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1219-1224.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wadowsky R.M., Wilson T.M., Kapp N.J., West A.J., Kuchta J.M., States S.J., Dowling J.N., Yee R.B. Multiplication of Legionella spp. in tap water containing Hartmannella vermiformis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991;57:1950–1955. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.7.1950-1955.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connell W.A., Dhand L., Cianciotto N.P. Infection of macrophage-like cells by Legionella species that have not been associated with disease. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:4381–4384. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.10.4381-4384.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maruta K., Miyamoto H., Hamada T., Ogawa M., Taniguchi H., Yoshida S.I. Entry and intracellular growth of Legionella dumoffii in alveolar epithelial cells. Am. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998;157:1967–1974. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9710108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scharf S., Vardarova K., Lang F., Schmeck B., Opitz B., Flieger A., Heuner K., Hippenstiel S., Suttorp N., N’Guessan P.D. Legionella pneumophila induces human beta Defensin-3 in pulmonary cells. Respir. Res. 2010;11:93. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scharf S., Hippenstiel S., Flieger A., Suttorp N., N’Guessan P.D. Induction of human β-defensin-2 in pulmonary epithelial cells by Legionella pneumophila: Involvement of TLR2 and TLR5, p38 MAPK, JNK, NF-κB, and AP-1. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2010;298:687–695. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00365.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bulet P., Stöcklin R. Insect antimicrobial peptides: Structures, properties and gene regulation. Prot. Pept. Lett. 2005;12:3–11. doi: 10.2174/0929866053406011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bulet P., Stöcklin R., Menin L. Anti-microbial peptides: From invertebrates to vertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 2004;198:169–184. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casteels P., Romagnolo J., Castle M., Casteels-Josson K., Erdjument-Bromage H., Tempst P. Biodiversity of apidaecin-type peptide antibiotics. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:26107–26115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee Y.S., Yun E.K., Jang W.S., Kim I., Lee J.H., Park S.Y., Ryu K.S., Seo S.J., Kim C.H., Lee I.H. Purification, cDNA cloning and expression of an insect defensin from the great wax moth, Galleria mellonella. Insect. Mol. Biol. 2004;13:65–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2004.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim C.H., Lee J.H., Kim I., Seo S.J., Son S.M., Lee K.Y. Purification and cDNA cloning of a cecropin-like peptide from the great wax moth, Galleria mellonella. Mol. Cells. 2004;17:262–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cytryńska M., Mak P., Zdybicka-Barabas A., Suder P., Jakubowicz T. Purification and characterization of eight peptides from Galleria mellonella immune hemolymph. Peptides. 2007;28:533–546. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown S.E., Howard A., Kasprzak A.B., Gordon K.H., East P.D. The discovery and analysis of a diverged family of novel antifungal moricin-like peptides in the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008;38:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown S.E., Howard A., Kasprzak A.B., Gordon K.H., East P.D. A peptidomic study reveals the impressive antimicrobial peptide arsenal of the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2009;39:792–800. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schuhmann B., Seitz V., Vilcinskas A., Podsiadlowski L. Cloning and expression of gallerimycin, an antifungal peptide expressed in immune response of greater wax moth larvae, Galleria mellonella. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 2003;53:125–133. doi: 10.1002/arch.10091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mak P., Chmiel D., Gacek G.J. Antibacterial peptides of the moth Galleria mellonella. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2001;48:1191–1195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weers P.M., Ryan R.O. Apolipophorin III: Role model apolipoprotein. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;36:231–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zdybicka-Barabas A., Cytryńska M. Involvement of apolipophorin III in antibacterial defense of Galleria mellonella larvae. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. 2011;158:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zdybicka-Barabas A., Januszanis B., Mak P., Cytryńska M. An atomic force microscopy study of Galleria mellonella apolipophorin III effect on bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:1896–1906. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hatters D.M., Peters-Libeu C.A., Weisgraber K.H. Apolipoprotein E structure: Insights into function. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahley R.W., Rall S.C., Jr Apolipoprotein E: Far more than a lipid transport protein. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 2000;1:507–537. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.1.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.De Bont N., Netea M.G., Demacker P.N.M., Verschueren I., Kullberg B.J., van Dijk K.W., van der Meer J.W., Stalenhoef A.F. Apolipoprotein E knock-out mice are highly susceptible to endotoxemia and Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. J. Lipid Res. 1999;40:680–685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roselaar S.E., Daugherty A. Apolipoprotein E-deficient mice have impaired innate immune responses to Listeria monocytogenes in vivo. J. Lipid Res. 1998;39:1740–1743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Oosten M., Rensen P.C., van Amersfoort E.S., van Eck M., van Dam A.M., Brevé J.J., Vogel T., Panet A., van Berkel T.J., Kuiper J. Apolipoprotein E protects against bacterial lipopolysaccharide-induced lethality. A new therapeutic approach to treat gram-negative sepsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:8820–8824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen L.T., Haney E.F., Vogel H.J. The expanding scope of antimicrobial peptide structures and their modes of action. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:464–472. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teixeira V., Feio M.J., Bastos M. Role of lipids in the interaction of antimicrobial peptides with membranes. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012;51:149–177. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mak P., Zdybicka-Barabas A., Cytryńska M. A different repertoire of Galleria mellonella antimicrobial peptides in larvae challenged with bacteria and fungi. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2010;34:1129–1136. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Harding C.R., Schroeder G.N., Reynolds S., Kosta A., Collins J.W., Mousnier A., Frankel G. Legionella pneumophila pathogenesis in the Galleria mellonella infection model. Infect. Immun. 2012;80:2780–2790. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00510-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palusinska-Szysz M., Kalitynski R., Russa R., Dawidowicz A.L., Drozanski W.J. Cellular envelope phospholipids from Legionella lytica. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;283:239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Palusinska-Szysz M., Janczarek M., Kalitynski R., Dawidowicz A.L., Russa R. Legionella bozemanae synthesizes phosphatidylcholine from exogenous choline. Microbiol. Res. 2011;166:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martínez-Morales F., Schobert M., López-Lara I.M., Geiger O. Pathways for phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis in bacteria. Microbiology. 2003;149:3461–3471. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26522-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang W., Smith D.K., Moulding K., Chen H.M. The dependence of membrane permeability by the antibacterial peptide cecropin B and its analogs, CB-1 and CB-3, on liposomes of different composition. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:27438–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lysenko E.S., Gould J., Bals R., Wilson J., Weiser J. Bacterial phosphorylcholine decreases susceptibility to the antimicrobial peptide LL-37/hCAP18 expressed in the upper respiratory tract. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:1664–1671. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1664-1671.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Verdon J., Labanowski J., Sahr T., Ferreira T., Lacombe C., Buchrieser C., Berjeaud J.M., Héchard Y. Fatty acid composition modulates sensitivity of Legionella pneumophila to warnericin RK, an antimicrobial peptide. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1808:1146–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koprivnjak T., Peschel A. Bacterial resistance mechanisms against host defense peptides. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2011;68:2243–2254. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0716-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skiada A., Markogiannakis A., Plachouras D., Daikos G.L. Adaptive resistance to cationic compounds in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2011;37:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Richards S.M., Strandberg K.L., Conroy M., Gunn J.S. Cationic antimicrobial peptides serve as activation signals for the Salmonella Typhimurium PhoPQ and PmrAB regulons in vitro and in vivo. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012;2 doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Al-Khodar S., Kalachikov S., Morozova I., Price C.T., Abu Kwaik Y. The PmrA/PmrB two-component system of Legionella pneumophila is a global regulator required for intracellular replication within macrophages and protozoa. Infect. Immun. 2009;77:374–386. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01081-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robey M., O’Connell W., Cianciotto N.P. Identification of Legionella pneumophila rcp, a pagP-like gene that confers resistance to cationic antimicrobial peptides and promotes intracellular infection. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:4276–4286. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.7.4276-4286.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edelstein P.H. Improved semiselective medium for isolation of Legionella pneumophila from contaminated clinical and environmental specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1981;14:298–303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.3.298-303.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schägger H., von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal. Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bradford M.M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White J.A., Hart R.J., Fry J.C. An evaluation of the Waters Pico-Tag system for the amino-acid analysis of food materials. J. Automat. Chem. 1986;8:170–177. doi: 10.1155/S1463924686000330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]