Abstract

Background

Trauma tertiary surveys (TTS) are advocated to reduce the rate of missed injuries in hospitalized trauma patients. Moreover, the missed injury rate can be a quality indicator of trauma care performance. Current variation of the definition of missed injury restricts interpretation of the effect of the TTS and limits the use of missed injury for benchmarking. Only a few studies have specifically assessed the effect of the TTS on missed injury. We aimed to systematically appraise these studies using outcomes of two common definitions of missed injury rates and long-term health outcomes.

Methods

A systematic review was performed. An electronic search (without language or publication restrictions) of the Cochrane Library, Medline and Ovid was used to identify studies assessing TTS with short-term measures of missed injuries and long-term health outcomes. ‘Missed injury’ was defined as either: Type I) any injury missed at primary and secondary survey and detected by the TTS; or Type II) any injury missed at primary and secondary survey and missed by the TTS, detected during hospital stay. Two authors independently selected studies. Risk of bias for observational studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

Results

Ten observational studies met our inclusion criteria. None was randomized and none reported long-term health outcomes. Their risk of bias varied considerably. Nine studies assessed Type I missed injury and found an overall rate of 4.3%. A single study reported Type II missed injury with a rate of 1.5%. Three studies reported outcome data on missed injuries for both control and intervention cohorts, with two reporting an increase in Type I missed injuries (3% vs. 7%, P<0.01), and one a decrease in Type II missed injuries (2.4% vs. 1.5%, P=0.01).

Conclusions

Overall Type I and Type II missed injury rates were 4.3% and 1.5%. Routine TTS performance increased Type I and reduced Type II missed injuries. However, evidence is sub-optimal: few observational studies, non-uniform outcome definitions and moderate risk of bias. Future studies should address these issues to allow for the use of missed injury rate as a quality indicator for trauma care performance and benchmarking.

Keywords: Tertiary survey, Missed injury, Multiple trauma, Patient safety, Quality of care

Background

Valid and reliable measures of trauma system performance are needed to guide improvement activities, benchmarking and research [1]. A common quality indicator in trauma care is missed injury, notwithstanding a systematic review finding limited validity and reliability [2].

Missed injuries occur in the time-critical and complex assessment of severely injured trauma patients in the Emergency Department (ED). Altered level of consciousness (from central nervous system injury, intoxication or sedation), distracting injury, or need for emergent surgery may impede adequate and detailed assessment of the patient. These initial examinations may therefore lead to injuries going undetected past the time when their management would avoid morbidity [3-14] or even mortality [5,7-9,15,16].

The trauma tertiary survey (TTS) is the proposed solution. It is an assessment undertaken after the episode of emergency care (including primary and secondary survey, emergency surgery and interventional radiology) and includes a comprehensive general physical re-examination and review of all investigations (diagnostic imaging and blood results) within 24 hours of admission [8,11,12], and repeated later when the patient is conscious, cooperative and mobilised [3,8,13].

Missed injury is most commonly defined as an injury missed at initial assessment up to 24 hours (including both primary and secondary survey and emergency intervention) [3,12,13]. With the TTS becoming part of standard trauma care, a second definition refers to injuries that were missed despite TTS performance [11]. Clearly then, the impact of a TTS on missed injuries will depend on which definition of missed injuries is used. An increase in detected injuries would be expected by the first definition, but a decrease of missed injuries by the second.

The TTS should be a useful tool for missed injury benchmarking. However, any benefits from performing routine TTS might be outweighed by excessive use of resources, or over-diagnosis (in which a TTS-identified injury has little or no effect on clinically relevant, long-term outcomes) [17]. Although the TTS should, by simple intuition, improve trauma care, we set out to test this empirically by systematically reviewing the literature. By doing so, we expect to facilitate the use of missed injury as a useful quality indicator in the future.

Aims

The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature to determine the effect of the TTS in hospitalized trauma patients on both types of missed injury rates (Type I - missed at initial management, but detected by TTS; Type II - missed at initial management and by TTS, detected during hospital stay) and long-term health outcomes.

Methods

Study eligibility

We considered any study assessing a TTS using randomized or quasi-randomized trials, observational studies such as cohort, case–control and before-and-after design studies. Subjects were trauma patients admitted to any hospital, with no limits regarding age, gender, or severity of trauma.

We included any study that used the TTS as an intervention alone or as part of a larger intervention (such as a change in hospital trauma system). The TTS was defined as a review of the admitted patient within 24 hours (or after regaining consciousness) and included at least a repeated full physical examination.

The primary outcome was missed injury, defined as Type I) any injury missed at initial management (primary and secondary survey and emergency intervention) and detected by TTS, or Type II) any injury missed at initial management and TTS, detected during hospital stay. The missed injury rate was the proportion of patients with a missed injury within the study population. Secondary outcomes included long-term health outcomes including rates of injuries detected after hospital discharge and ability to return to pre-injury functional status. Eligible studies had to include either the primary or secondary outcome.

Search strategy and information sources

Relevant studies were identified using electronic searches of MEDLINE (1966 to December 2010) and OVID (1980 to December 2010) and the Cochrane Library Central Registry of controlled trials, without language restrictions. The following key words were used to conduct the search: tertiary survey, trauma survey, traumatology, diagnostic errors, delayed diagnosis, missed diagnosis, missed injury, prognosis and long-term outcomes. The full search strategy is contained in Additional file 1.

Selection of studies

Two reviewers (GK and GG) independently assessed all titles and abstracts for potential relevant articles, with any disagreement adjudicated by a third reviewer (LG). We retrieved the full-text article of any reference that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. The eligibility of the full-text articles was assessed against the criteria of a standardized form.

Data extraction and management

The following data were extracted from the studies: title, year of publication, country of study, study design, number of participants, age and gender of participants, injury severity score (median ISS, proportion with ISS>15), mechanism of trauma (blunt vs. penetrating), presence of an altered level of consciousness and admission to intensive care unit (ICU). The outcome parameters on missed injury rates and long-term outcomes were collected when available. Authors were contacted in order to obtain missing data. We attempted meta-analysis to quantify and summarize results, but due to the inherent bias of the studies and the extent of the heterogeneity [18,19], meta-analysis was deemed invalid and hence not reported. Primary and secondary outcomes were all proportions. Results of studies were pooled using simple weighted averages. Chi-square test was used to test for differences in proportions.

Since we anticipated possible differences in outcomes for certain demographic groups, we defined potential subgroups for analysis a priori, which included; age, gender, ISS (ISS>15), injury mechanism (blunt vs. penetrating), altered level of consciousness and ICU admission.

Assessment of risk of bias

Two of us (GK and GG) independently used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale [20] to assess the quality of non-randomized observational studies (Additional file 2). We classified studies to either low, moderate or high risk of bias if there were respectively up to 1, 2–3 or >3 inadequate items.

This systematic review was conducted to conform to the PRISMA standard (http://www.prisma-statement.org).

Results

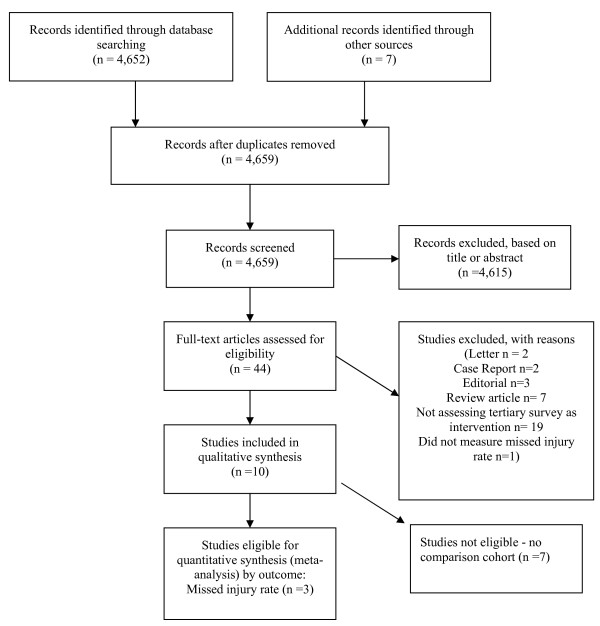

Our search identified a total of 4,659 of potentially relevant references. We discarded 4,615 after examining their Title or Abstract. The full-text articles of the remaining 44 were retrieved: 10 studies [3,11-13,21-25] were included in the review, (of which three were suitable for meta-analysis, Figure 1; Table 1). None were randomized or quasi-randomized trials, that is, all 10 included studies were observational, (seven prospective cohort studies [8,12,13,22-25]; one prospective cohort study with historical comparison [1]; and two cohort studies with a before-and-after design [11,21]).

Figure 1.

Selection of studies.

Table 1.

Description of included studies

| Author, year, origin | Population (number and description) | Population characteristics (Age, Gender, Mechanism, ISS) | Intervention | Outcome measure | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enderson, 1990, Tennessee, USA |

399 admitted trauma patients |

Age>15 yrs: 86% |

TTS as part of trauma admission form, conducted within 24–48 hours after patient stabilization |

Missed injuries – defined as detected as a result of TTS. (Type I) |

Prospective cohort study – comparing with historical summary data |

| Gender: N/A | |||||

| Mechanism: 89% | |||||

| Blunt Mean ISS: 21 | |||||

| Biffl, 2003 |

All admitted trauma patients. |

Mean Age: 45.3 vs. 44.5 yrs |

Implementation of formal TTS, using standardized form and TTS policy. TS within 24 hours and after ICU discharge |

Missed injury rate – defined as injuries detected after 24 hours admission or injuries missed by TTS. (Type II) |

Cohort study with before-and-after design |

| Rhode Island, USA |

Before: 3,412 |

Gender: 63% vs. 64% Male |

|||

| After: 3,442 |

Mechanism: N/A |

||||

| Mean ISS: 10.7 vs. 10.7 | |||||

| Vles, 2003 |

All (3,879) admitted trauma patients |

Age: N/A |

Use of standard trauma forms, TTS and review of radiology within 24 hours |

Missed injury rate – Any injury missed on primary and secondary survey. (Type I) |

Prospective cohort study |

| The Netherlands |

Gender: N/A |

||||

| Mechanism: N/A | |||||

| ISS>16: 1.2% | |||||

| Hoff, 2004 |

432 admitted trauma patients |

Age: N/A |

Formal radiology rounds as part of TTS |

Missed injury or ‘new diagnosis’ as result of radiology rounds with trauma surgeons. (Type I) |

Prospective cohort study |

| Pennsylvania, USA |

Gender: N/A |

||||

| Mechanism: N/A | |||||

| ISS: N/A | |||||

| Soundappan, 2004 |

76 children admitted with ISS>9 |

Mean Age: 8.5 yrs |

TTS performed using standardized from by trauma fellow on day after admission and after extubation |

Missed injury rate – Any injury missed on primary and secondary survey. (Type I) |

Prospective cohort study |

| Sydney, Australia |

Gender: 66% Male |

||||

| Mechanism: 100% Blunt | |||||

| Mean ISS: 15 | |||||

| Howard, 2006 |

90 admitted trauma patients |

Age: N/A |

TTS performed using standardized from by single clinician within 24 hours |

Missed injury rate – Any injury detected on the TTS. (Type I) |

Prospective cohort study |

| Indianapolis, USA |

Gender: 74% Male |

||||

| Mechanism: N/A | |||||

| ISS: N/A | |||||

| Okello, 2007 |

403 admitted trauma patients |

Mean Age: 29 yrs |

Daily physical examination up to 30 days, including TTS in first 24 hours |

Missed Injury – unclear definition – implied as injury detected after primary and secondary survey. (Type I) |

Prospective cohort study |

| Uganda |

Gender: 82% Male |

||||

| Mechanism: 91% Blunt | |||||

| ISS: N/A | |||||

| Janjua, 2008 |

206 admitted trauma patients |

Mean Age: 35 yrs |

TTS performed by trauma fellow within 24 hours and after regaining consciousness |

Missed injury rate – Any injury missed on primary and secondary survey and operating room. (Type I) |

Prospective cohort study |

| Sydney, Australia |

Gender: 75% Male |

||||

| Mechanism: 91-100% Blunt | |||||

| ISS: N/A | |||||

| Ursic, 2009 |

All admitted trauma patients. |

Mean Age: 43.4 vs. 44.4 yrs Gender: 69.4% vs 68.9% Male Mechanism:94.3 vs. 94.4% Blunt ISS>15: 26% vs 31% |

Implementation of a dedicated trauma service, which included a formalised TTS |

Mortality and Length of Hospital stay. Missed injury – not in article -data retrieved via author communication - any injury missed at primary and secondary survey. (Type I) |

Cohort study with before-and-after design |

| Sydney, Australia |

Before: 981 |

||||

| After: 1,006 | |||||

| Huynh, 2010 |

5,143 admitted trauma patients | Mean Age: 36.2 yrs |

Mid level providers performed TTS using a form within 48 hours. This was reviewed by trauma surgeon | Missed injury – defined as detected at TTS. (Type I) | Prospective cohort study |

| North Carolina, USA | Gender: 71% Male |

||||

| Mechanism: 85% Blunt | |||||

| Mean ISS: 14.2 |

ISS Injury Severity Score, TTS Tertiary Survey, USA United States of America.

The risk of bias was low for two studies [11,21] and moderate in the remaining eight (Additional file 2). The selection of participants in all studies was by consecutively admitted trauma patients, ensuring appropriate representativeness and minimizing selection bias. All ten studies used either medical records or a special form to determine whether a TTS had occurred. Seven studies did not have a comparison cohort (i.e. a cohort without TTS performed), increasing their risk of bias [8,12,13,22-25]. There was insufficient information to assess the comparability section of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for eight studies. The remaining two studies [11,21] had comparable demographics for exposed and non-exposed cohorts. One study had a higher admission rate to the trauma ICU in the cohort receiving the TTS compared to those in the cohort who did not (30% vs. 20% admission rate) [11].

Missed injury rate – in patients receiving TTS

Nine [3,12,13,21-25] of the included studies used Type I missed injury as outcome (missed at primary and secondary survey and detected by TTS), with the remaining single other study [11] utilizing Type II missed injury (injury missed by both initial assessment and the TTS).

Type I missed injury rate – in patients receiving TTS

The overall Type I missed injury rate in cohorts with a TTS conducted was 4.3% (Table 2). The two largest studies [12,23] had similar Type I missed injury rates (1.3% and 1.6%, respectively), while a medium-sized study [21] had a Type I missed injury rate of 6.2% (unpublished data provided by author). The remaining studies reported Type I missed injury rates varying from 9.3 to 19.3%, with one small study [8] being an outlier (65%). In this study, a dedicated trauma surgery fellow aware of the purpose of the study performed all tertiary surveys.

Table 2.

Outcomes – Type I missed injury rates

|

PRE TTS implementation |

POST TTS implementation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missed injuries | Study population (N) | Missed injury rate (%) | Patients with Missed injuries (N) | Study population (N) | Missed injury rate (%) | |

| Enderson, 1990 |

|

N/A |

2.0 |

37 |

399 |

9.27 |

| Vles, 2003 |

|

|

|

49 |

3,879 |

1.26 |

| Hoff, 2004 |

|

|

|

42 |

432 |

9.72 |

| Soundappan, 2004 |

|

|

|

12 |

76 |

15.8 |

| Howard, 2006 |

|

|

|

12 |

90 |

13.3 |

| Okello, 2007 |

|

|

|

78 |

403 |

19.4 |

| Janjua, 2008 |

|

|

|

134 |

206 |

65.0 |

| Ursic, 2009 |

35 |

981 |

3.57 |

62 |

1,006 |

6.16 |

| Huynh, 2010 |

|

|

|

80 |

5,143 |

1.56 |

| Overall | 35 | 981 | 3.57 | 506 | 11,634 | 4.35 |

Injuries missed at initial assessment, detected by TTS.

TTS Tertiary Survey, N/A not avaible – a similar population size is assumed (N=399).

Type II missed injury rate – in patients receiving TTS

Only one study reported Type II missed injury, with a rate of 1.51% after TTS introduction [11] Table 3.

Table 3.

Outcomes – Type II missed injury rates

|

PRE Tertiary survey implementation |

POST Tertiary survey implementation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Missed injuries | Study population (N) | Missed injury rate (%) | Missed injuries | Study population (N) | Missed injury rate (%) | |

| Biffl, 2003 |

81 |

3,412 |

2.37 |

52 |

3,442 |

1.51 |

| Overall | 81 | 3,412 | 2.37 | 52 | 3,442 | 1.51 |

Injuries missed at initial assessement and by TTS, detected in-hospital.

TTS Tertiary Survey.

Type I and II missed injury rate – before and after introduction of TTS

Two studies [3,21] compared Type I missed injury and one study [11] compared Type II missed injury using before and after studies. Type I missed injuries increased as a result of the TTS (3% vs. 7%, P < 0.01), and type II missed injuries decreased (2.4% vs. 1.5%, P = 0.01).

Clinical relevance of missed injuries

Table 4 summarizes the anatomical areas of missed injury, change in management and resultant morbidity or mortality as reported by the individual studies. There was a large variation in anatomical distribution of missed injuries, with orthopaedic extremity injuries, spine related injuries and facial injuries most commonly reported. The proportion of patients with missed injury requiring surgical intervention varied between 10-30%, which equates to 0.1-5% of the total population of these studies [3,8,12,13,22,23]. Only two deaths were reported specifically as a result of a missed injury [8].

Table 4.

Description of missed injuries

| Author, year, origin, N | (N)with MI | Area involved | % | (N)with clinically significant MI | Description of change in management | Mortality and morbidity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enderson, 1990, Tennessee, USA N=399 |

36 |

MSK |

51 |

7 |

OT, N= 7 |

Nil deaths |

| Spinal |

12 |

(MSK N=3, Facial N=1, Abdomen N=3) |

Stroke, N=1 |

|||

| Facial |

5 |

|||||

| Thoracic |

12 |

|||||

| Abdominal |

15 |

|||||

| Vascular |

5 |

|||||

| Biffl, 2003, |

81 vs. 52 |

MSK |

32 vs. 46 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported |

| Rhode Island, USA |

Spinal |

29 vs. 24 |

||||

| Pre TTS: N= 3412 vs. Post TTS: 3442 |

Abdominal |

17 vs. 18 |

||||

| Brain |

10 vs. 6 |

|||||

| Pelvic |

5 vs. 0 |

|||||

| Vascular |

3 vs. 2 |

|||||

| Diaphragm |

3 vs. 0 |

|||||

| Vles, 2003, |

49 |

Chest |

33 |

22 |

OT, N=12 |

Morbidity unspecified, N=3 |

| The Netherlands N=3879 |

MSK |

27 |

(Chest N=1, MSK N=4, Facial N=5, Other N=2) |

|||

| Skull |

7 |

ICC, N=2 |

||||

| Facial |

13 |

Cast, N=6 |

||||

| C-Spine |

7 |

|||||

| Other |

10 |

Halo/brace, N=2 |

||||

| Hoff, 2004 |

42 |

Extremities |

45 |

19 |

OT, N=4 (not specified) |

Not reported |

| Pennsylvania, USA |

Spine |

21 |

Cast, N=7 |

|||

| N=432 |

Chest |

15 |

Transfer, N=1 |

|||

| Pelvis/proximal skeleton |

19 |

Change in advice, N=6, Home equipment, N=1 |

||||

| Soundappan, 2004 |

12 |

Head/face |

33 |

1 |

OT, N=1 (not specified) |

Nil deaths |

| Sydney, Australia |

Spine |

17 |

Prolonged LOS, N=4 |

|||

| N=76 |

Extremities |

50 |

Delay in mobilisation, N=4 |

|||

| Howard, 2006, |

13 |

Extremities |

70 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported |

| Indianapolis, USA |

Face |

12 |

||||

| N=90 |

Spine |

12 |

||||

| Chest |

6 |

|||||

| Okello, 2007, |

76 |

Head and neck |

24 |

Not reported |

Not reported |

Not reported |

| Uganda |

Face |

8 |

Mulivariate regression shows higher morbidity and longer LOS in patients with MI compared to patients without MI. This may not reflect causality. |

|||

| N=403 |

Thorax |

11 |

||||

| Abdomen/pelvis |

20 |

|||||

| Extremities |

26 |

|||||

| Janjua, 2008 |

134 |

MSK |

40 |

30 |

OT, N=11 (Orthopedic n=3, Laparatomy N=7, |

Death 1.5% (N=2: C1 fracture; epidural hematoma) |

| Sydney, Australia |

STI |

36 |

Thoracotomy N=1) |

Complications 8% (peritonitis N=4 after missed hollow viscus injury) |

||

| Abdomen |

6 |

Laceration repair, N=2 |

||||

| N=206 |

Nerve injury |

9 |

Embolisation, N=1 |

|||

| (Hemo-) Pneumothorax |

5 |

Not specified, N=17 |

||||

| Ursic, 2009 |

35 vs 62 |

Not reported |

|

Not reported |

Not reported |

Mortality |

| Sydney, Australia |

Pre 3.5% vs. post 2.5% |

|||||

| Pre TTS: N=981 vs. Post TTS= 1006 | ||||||

| Huynh, 2010 |

80 |

Orthopedic |

60 |

31 | OT, N=7 (Orthopedic N=4, Facial N=2, Spinal N=1) |

Not reported |

| North Carolina, USA |

Facial/plastics/dental |

21 |

Cast, N=24 | |||

| N=5143 |

Neurosurgical |

16 |

||||

| Ophthalmology | 3 |

Description of missed injuries. Anatomical area, clinically significant missed injuries, change in management and mortality and morbidity.

MI Missed Injury, OT operating Theatre, ISS Injury Severity Score, TS Tertiary Survey, USA United States of America, MSK musculoskeletal. Not all columns add up to 100% due to low proportions not being reported.

TTS Tertiary Trauma Survey.

Subgroup analyses

Only one study investigated a difference in missed injury rates after introduction of a TTS for any of the pre-defined subgroups [11]. It reported a decrease in Type II missed injuries in patients admitted to a trauma intensive care unit (5.7% vs. 3.4%, P < 0.05). Another reported a paediatric trauma population (Type I missed injury rate: 15.8%), but did not specifically investigate age as a factor of interest [13]. A third study reported a lower mortality trend (5.4% vs. 4.1%, P = 0.17) associated with a higher detection of Type I missed injuries by TTS, introduced as part of a trauma service (3.6% vs. 6.2%, P < 0.01, via author communication) [21].

No other included study assessed differences in (any type of) missed injury rate after introduction of a TTS for the other pre-defined subgroups (age, gender, ISS, mechanism of injury or altered level of consciousness).

Long-term health outcomes

No studies that assessed the effect of the TTS on long-term health outcome were identified.

Completeness of data

Data for the two studies included in the analysis of the systematic review (using missed injury rate at initial assessment, detected by TTS) were not complete in the original publications. One quoted a historical overall missed injury rate of 2% (without data on sample size) [3] and another did not report missed injury data in the published manuscript [21]: we obtained this information by writing to the authors directly.

Discussion

This systematic review found empirical evidence that the TTS improves trauma care by increasing Type I missed injuries and reducing Type II missed injuries.

Limitations

Our findings were based on weak evidence: there were no relevant randomized studies, so only observational studies with their inherent risk of bias were available. Meta-analysis was attempted, but due to few studies being eligible and being prone to bias as well as substantial heterogeneity, we have not reported this. We were unable to assess the effect of TTSs on morbidity, so any improvement in patient outcomes consequent on reduction in missed injuries has to be inferred.

Other shortcomings included variation in the trauma patient populations (one study including paediatric trauma patients only [13]); geography (with one study conducted in Uganda [24] where trauma patterns and trauma care may be different from those of the other studies); and in the intervention (differently defined in two studies - one study [22] aimed to decrease missed injuries by formalizing the radiology review component of the TTS, while another [21] assessed the effect of implementing a complete trauma service, of which a TTS was a component).

The definition of missed injury varied between studies: one study defined missed injury as any injury that escaped detection at time of the TTS [11], (i.e. Type II). The other nine studies, including two before-and-after studies, used the more commonly used ‘any injury missed by primary and secondary survey, and detected as a result of the TTS’ (i.e. Type I), which really represents a delayed diagnosis (or increase in injury detection). For example, in one study [21] the TTS was associated with increased missed injury rate, but reduced mortality. This seems counter-intuitive until one realises this is related to Type I missed injuries, leading to more frequent detection at 24 hours by TTS.

This systematic review highlights several issues. Firstly missed injury needs a consistent, clear and expanded definition to facilitate future research and provide a tool for benchmarking. The use of these differences in definition precludes overall comparison of studies and need to be made explicit in order to legitimately compare studies. We propose a classification of missed injuries (Table 5). It is likely that the third group in this proposed classification (Type III: missed injury detected after hospital discharge) has been under-reported, since there are no published data.

Table 5.

Missed injury classification

| Missed injury type | Description |

|---|---|

|

Type I |

Before TTS or as result of TTS: |

| Injury missed at initial assessment (primary and secondary survey and emergency intervention), but detected within 24 hours, before or through formal TTS (i.e. delayed diagnosis at 24 hours) | |

| (Injury missed at initial assessment) | |

|

Type II |

After TTS, during hospital stay: |

| Injury missed by TTS, detected in hospital after 24 hours. | |

| (Injury missed at initial assessment and TTS) | |

| Type III |

After TTS, after hospital discharge: |

| Injury missed during hospital stay including TTS, detected after hospital discharge. | |

| (Injury missed at initial assessment and TTS and hospital stay) |

Secondly, for the nine studies using the Type I missed injury definition, a mean injury detection rate of 4.3% was found. This can be used as a yardstick to compare future studies assessing Type I missed injuries. This may yet be an over-estimation of Type I missed injuries (or rather, delayed diagnoses), since the reported missed injury rate was approximately 1.5% in the two larger studies that together included more than 9,000 subjects and where investigator bias would have been minimal.

Furthermore, we summarized the anatomical distribution of missed injuries and how this changed management as reported by the individual studies (Table 4). This relates to the clinical relevance of these injuries, since it would be reasonable to expect at least delayed recovery or even prolonged morbidity without these interventions. Very few deaths as a result of a missed injury were reported and need for a change in management in the form of surgical intervention was variable or not reported. None of the studies included in this systematic review pre-defined clinical significance in the design of the study. Three studies discussed clinical relevance of missed injuries, with the common denominator being whether the missed injury would have lead to morbidity or mortality as judged by expert opinion (Table 6). Interestingly, one study defined a clinically significant missed injury as any change in management, including ordering further imaging [22]. We did not pre-define clinically relevant missed injury as an outcome of this systematic review. The available data suggests that the current literature does not have a widely agreed definition for clinically significant missed injury, evidenced by the variable reporting and outcomes. A more consistent and reproducible approach to this issue is warranted. Very few studies related the TTS to morbidity and mortality and as such we cannot comment on the effect the TTS had on patient outcomes.

Table 6.

Definitions of clinically significant missed injury amongst included studies

| Author | Description |

|---|---|

| Hoff et al. |

Level 1 - Missed injury would likely lead to morbidity/mortality |

|

Level 2- Missed injury alters care in hospital (including additional imaging) | |

| Vles et al. |

Any missed injury that leads to change in treatment resulting from the detection of the missed injury |

| Huynh et al. | Clinically significant missed injuries are injuries that are judged as such by the trauma attending and required intervention |

Lastly, we found no reporting of long-term outcomes after TTS. Studies have reported long-term outcomes for the multiple injured patients [26] or subgroups of patients with specific injuries [27], but not the effect of the TTS per se.

Conclusions

In cohorts with a TTS conducted, the Type I missed injury rate was 4.3% and Type II missed injury rate was 1.5%. The TTS increased Type I missed injuries (or injury detection by TTS), and decreased Type II missed injuries (less injuries missed by TTS). This is based on few studies with risk of bias, and as such the clinical effect of TTS is not fully known. This review emphasizes the lack of studies reporting long-term outcomes after a TTS. This may be due to assumed benefits of the TTS. Quantifying the actual effect on longer-term health outcomes, including missed injuries after hospital discharge, may support a more structured and widespread use of the TTS. Future studies using consistent outcome definitions are warranted to allow for the use of missed injury rate as a quality indicator for trauma care performance and benchmarking.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Design and concept (all authors), literature search (GK and GG), data extraction (GK and GG), data adjudication (LG), data analysis (GK), data interpretation (GK, LG, CdM), manuscript drafts and approval of final manuscript (All authors), responsibility for paper as a whole (GK). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Complete Search Strategy.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies20.

Contributor Information

Gerben B Keijzers, Email: gerben_keijzers@health.qld.gov.au.

Georgios F Giannakopoulos, Email: g.giannakopolous@vumc.nl.

Chris Del Mar, Email: cdelmar@bond.edu.au.

Fred C Bakker, Email: fc.bakker@vumc.nl.

Leo MG Geeraedts, Jr, Email: l.geeraedts@vumc.nl.

Acknowledgements

Assistant Professor Michael Steele for statistical advice.

Queensland Emergency Medicine Research Foundation (QEMRF).

Meetings: Accepted for to ESTES (Basel, May 2012) and ICEM (Dublin, June 2012).

References

- Gruen RL, Gabbe BJ, Stelfox HT, Cameron PA. Indicators of the quality of trauma care and the performance of trauma systems. Br J Surg. 2012;99(Suppl 1):97–104. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stelfox HT, Straus SE, Nathens A, Bobranska-Artiuch B. Evidence for quality indicators to evaluate adult trauma care: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:846–859. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31820a859a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enderson BL, Reath DB, Meadors J, Dallas W, DeBoo JM, Maull KI. The tertiary trauma survey: a prospective study of missed injury. J Trauma. 1990;30:666–670. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199006000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frawley PA. Missed injuries in the multiply traumatized. Aust N Z J Surg. 1993;63:935–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1993.tb01722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aaland MO, Smith K. Delayed diagnosis in a rural trauma center. Surgery. 1996;120:774–779. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(96)80030-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R, Mattox R, Collins T, Parks-Miller C, Eidt J, Cone J. Missed injuries in a rural trauma center. Am J Surg. 1996;172:564–567. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(96)00247-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnival RA, Woodward GA, Schunk JE. Delayed diagnosis of injury in pediatric trauma. Pediatrics. 1996;98:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjua KJ, Sugrue M, Deane SA. Prospective evaluation of early missed injuries and the role of tertiary trauma survey. J Trauma. 1998;44:1000–1007. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199806000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buduhan G, Donna I. McRitchie. Missed injuries in patients with multiple trauma. J Trauma. 2000;49:600–605. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houshian S, Larsen MS, Holm C. Missed injuries in a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2002;52:715–719. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200204000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biffl WL, Harrington DT, Cioffi WG. Implementation of a tertiary trauma survey decreases missed injuries. J Trauma. 2003;54:38–44. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200301000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vles WJ, Veen EJ, Roukema JA, Meeuwis JD, Leenen LP. Consequences of delayed diagnoses in trauma patients: a prospective study. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:596–602. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00601-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundappan SV, Holland AJ, Cass DT. Role of an extended tertiary survey in detecting missed injuries in children. J Trauma. 2004;57:114–118. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000108992.51091.F7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks A, Holroyd B, Riley B. Missed injury in major trauma patients. Injury. 2004;35:407–410. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(03)00219-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrektsen SB, Thomsen JL. Detection of injuries in traumatic deaths: the significance of medico-legal autopsy. Forensic Sci Int. 1989;42:135–143. doi: 10.1016/0379-0738(89)90206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stothert JC Jr, Gbaanador GB, Herndon DN. The role of autopsy in death resulting from trauma. J Trauma. 1990;30:1021–1026. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199008000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosed. Making people sick in the pursuit of health. Boston Mass: Beacon Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of non-randomised studies in metaanalyses. 2011. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- Ursic C, Curtis K, Zou Y, Black D. Improved trauma patient outcomes after implementation of a dedicated trauma admitting service. Injury. 2007;38:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff WS, Sicoutris CP, Lee SY, Rotondo MF, Holstein JJ, Gracias VH, Pryor JP, Reilly PM, Doroski KK, Schwab WC. Formalized radiology rounds: the final component of the tertiary survey. J Trauma. 2004;56:291–295. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000105924.37441.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh TT, Blackburn AH, McMiddleton-Nyatui D, Moran KR, Thomason MH, Jacobs DG. An initiative by midlevel providers to conduct tertiary surveys at a level I trauma center. J Trauma. 2010;68:1052–1058. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181d87789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okello CR, Ezati IA, Gakwaya AM. Missed injuries: a Ugandan experience. Injury. 2007;38:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2006.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Sundararajan R, Thomas SG, Walsh M, Sundararajan M. Reducing missed injuries at a level II trauma center. J Trauma Nurs. 2006;13:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00043860-200607000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel J, Youssef M, Pfeifer R, Ramirez JM, Probst C, Sellei R, Zelle BA, Sittaro NA, Khalifa F, Pape HC. Health-related quality of life in patients with multiple injuries and traumatic brain injury 10+ years postinjury. J Trauma. 2010;69:523–530. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181e90c24. Discussion 530–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy ML, MacKenzie EJ, Durbin DR, Aitken ME, Jaffe KM, Paidas CM, Slomine BS, Dorsch AM, Christensen JR, Ding R. Children’s health after trauma study group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:252–260. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Complete Search Strategy.

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies20.