Abstract

The proportion in which carbon and growth-limiting nutrients are exported from the oceans’ productive surface layer to the deep sea is a crucial parameter in models of the biological carbon pump. Based on >400 vertical flux observations of particulate organic carbon (POC) and nitrogen (PON) from the European Arctic Ocean we show the common assumption of constant C:N stoichiometry not to be met. Exported POC:PON ratios exceeded the classical Redfield atomic ratio of 6.625 in the entire region, with the largest deviation in the deep Central Arctic Ocean. In this part the mean exported POC:PON ratio of 9.7 (a:a) implies c. 40% higher carbon export compared to Redfield-based estimates. When spatially integrated, the potential POC export in the European Arctic was 10–30% higher than suggested by calculations based on constant POC:PON ratios. We further demonstrate that the exported POC:PON ratio varies regionally in relation to nitrate-based new production over geographical scales that range from the Arctic to the subtropics, being highest in the least productive oligotrophic Central Arctic Ocean and subtropical gyres. Accounting for variations in export stoichiometry among systems of different productivity will improve the ability of models to resolve regional patterns in carbon export and, hence, the oceans’ contribution to the global carbon cycle will be predicted more accurately.

Introduction

The concept of new vs. regenerated primary production sensu Dugdale and Goering (1967) [1] has profoundly shaped the understanding of biological production and carbon sequestration in the ocean. The revelation that new production based on allochthonous nutrients supplied to the surface layer approximates export of organic matter to the deep ocean [2] has been widely adopted as a law of nature in ecosystem models used to quantify the contribution of the oceans’ biological carbon pump to the global carbon cycle. While export from a steady-state system must be balanced by an equivalently large input of new nutrients, recycling of carbon and growth-limiting nutrients by the pelagic food web profoundly impacts the potential of a system to export carbon [3], [4]. Because organic nitrogen is remineralised faster than carbon in large parts of the ocean [5], the common assumption of constant elemental stoichiometry (e.g. Redfield) for converting nitrogen export to carbon typically underestimates the strength of the biological carbon pump and therefore carbon export (e.g. [6]). Assuming that C:N is constant over spatially heterogeneous environments also constrains the ability of models to resolve regional patterns in carbon export, which are crucial for understanding ecosystem functioning. Model experiments with a depth-dependent particulate organic C:N ratio significantly increased carbon sequestration compared to a constant ratio model [7]. Furthermore, carbon overconsumption in response to increased atmospheric CO2 is suggested to increase the spread of suboxic regions in the ocean due to respiration of excess carbon exported from the surface layer [8]. These findings suggest that our ability to predict how perturbations to the ocean environment affect the marine ecosystem in part depend on our understanding of the stoichiometric coupling between carbon and nutrients. At present, knowledge of the regulation of exported C:N is limited which poses a constraint to further development of ecosystems models. Because nitrogen recycling within the euphotic zone varies regionally with primary production [2], export stoichiometry and, hence, the efficiency of the biological carbon pump should reflect nutrient availability or trophic state (oligo-, meso-, eutrophy) of pelagic ecosystems.

We use published and unpublished data on vertical flux of particulate organic carbon (POC) and nitrogen (PON) from the European Arctic Ocean to test the hypothesis of constant export stoichiometry. The same methodology was adopted in all studies in this region, which allows comparisons of the data among regions in order to determine spatial patterns. The Arctic Ocean was also not included in a previous synthesis of export stoichiometry [9]. Furthermore, we assess the anticipated relationship between nitrate-based new production as a measure of trophic state and export stoichiometry over large geographical scale based on published data from other primarily nitrogen-limited parts of the World Ocean.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection Analytical Methods

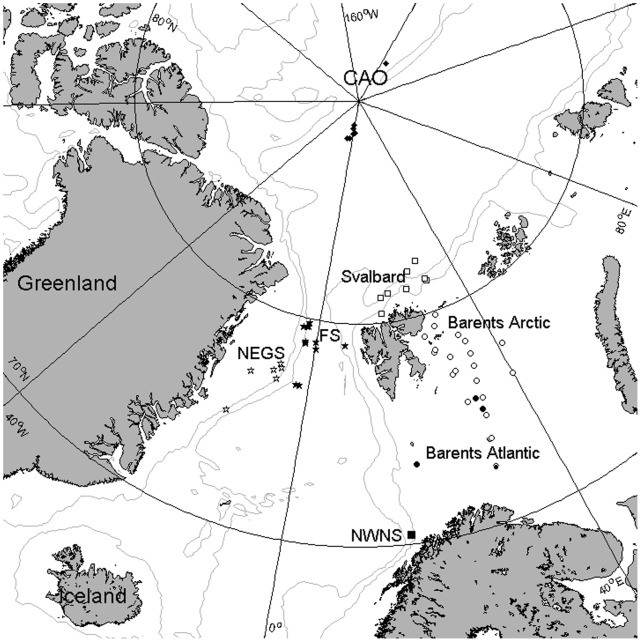

Vertical export in the European Arctic Ocean was determined by means of short-term deployed surface-tethered drifting sediment traps at a total of 64 stations or occasions (Fig. 1). Between 1 and 14 sediment traps were used to collect sinking particulate matter in the 20–200 m depth range. A typical array consisted of traps situated at 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 90, 120 and 200 m depth, and was attached to a surface-tethered float or a drifting ice floe and deployed for circa 24 h without preservatives. The sediment traps consisted of duplicate parallel cylinders (height:diameter ratio 6.25) mounted in a gimballed frame equipped with a vane. The cylinders maintain vertical orientation perpendicular to the current direction at the moderate current velocities prevailing under all deployments [10]. The trapping efficiency for particulate organic carbon is 90–110%, determined by comparison with the 234Thorium method, and the traps therefore provide reliable estimates of particle fluxes [10].The observations were a priori grouped into seven sub-regions based on the dominant water mass, ice conditions, and bottom depth (Table 1). The observations are temporally constrained to the productive season (March-August), but the temporal resolution and distribution of observations over the season vary among regions.

Figure 1. Map of the European Arctic with locations of sediment trap deployments indicated according to the defined sub-regions: Central Arctic Ocean (CAO, black diamonds), Fram Strait (FS, black pentagrams), NE Greenland Shelf (NEGS, white pentagrams), Svalbard shelf break (Svalbard, white squares), Barents Sea Arctic (Barents Arctic, white circles), Barents Sea Atlantic (Barents Atlantic, black circles), and NW Norwegian shelf (NWNS, black square).

Locations visited more than once have overlapping symbols. The NWNS was visited 6 times in the same year. Bathymetry (grey lines) is indicated by the 500 and 2000 m isobaths.

Table 1. Characteristics of sub-regions of the European Artic Ocean.

| Region | Stations (n) | Bottom depth (m) | Ice type | Water masses | Origin of data |

| Central Arctic Ocean | 7 | 2500–4000 | MYI | ArW, AtW (below 250 m) | [25] |

| Svalbard shelf break | 8 | 300–3700 | FYI | ArW, SMW, mAtW (below 50 m) | [18], [26], [27], K.O. unpubl |

| Fram Strait | 11 | 1000–3200 | FYI | ArW, AtW | [28], M.R. unpubl |

| NE Greenland shelf | 6 | 250–310 | FYI | ArW, SMW, AtW (below 100 m) | M.R. unpubl |

| Barents Sea Arctic | 19 | 170–350 | FYI | ArW, AtW (in trenches) | [11], [18], [26] |

| Barents Sea Atlantic | 7 | 220–480 | None | AtW | [11], [26] |

| NW Norwegian shelf | 6 | 500 | None | AtW, NCW | [29] |

Ice types are multi-year ice (MYI) and first-year ice (FYI). Water masses are Arctic Water (ArW), Atlantic Water (AtW), Surface Melt Water (SMW), modified Atlantic Water (cooled and diluted; mAtW), and Norwegian Coastal Water (NCW), as defined by Sundfjord et al. 2007 [13].

Particulate organic carbon (POC) and nitrogen (PON) were determined in GF/F filter samples of the sediment trap content using an elemental CHN analyser. The filters were dried and exposed to HCl fumes in order to remove inorganic carbon prior to analyses [11]. POC and PON values were corrected for background contamination determined in blank filters. POC and PON fluxes in units of mass were converted to molar unit using the atomic weights of C and N.

Exported POC:PON and new production from other parts of the World Ocean were obtained from the literature. Only observations from the upper 500 m of the water column were included in order to allow comparisons with the data from the Arctic Ocean (Table 2). New production in the European Arctic Ocean was simulated [6] and published values from other regions were mostly based on nitrate inventories (Table 2). Data on new production were in most cases available in units of carbon based on conversion from nitrate uptake to carbon using either observed DIC:NO3 drawdown ratios or Redfield C:N. Where new production was available only in units of nitrogen (W Sargasso Sea), it was converted to carbon using the Redfield C:N ratio.

Table 2. Mean exported POC:PON ratio (mean±SD (SE)) of particulate organic matter sampled by means of sediment traps, and mean annual new production (NP) in regions included in Fig. 4, with reference to source.

| Region, abbreviation | Obs | Trap depth | POC:PON | Comments | Ref POC:PON | NP | NP method | Ref NP |

| (n) | (m) | (a:a) | (mol C m−2 yr−1) | |||||

| Central Arctic Ocean, CAO | 54 | 20–200 | 9.7±1.5 (0.2) | August | This study | 1.0 | Model; 19-year mean | This study |

| Svalbard shelf break, Svalbard | 31 | 20–200 | 7.7±1.5 (0.3) | May, July | This study | 2.4 | Model; 19-year mean | This study |

| Fram Strait, FS | 86 | 20–200 | 7.7±2.3 (0.2) | April-June, August | This study | 5.8 | Model; 19-year mean | This study |

| NE Greenland shelf, NEGS | 48 | 20–200 | 8.9±2.0 (0.3) | April-May | This study | 4.2 | Model; 19-year mean | This study |

| Barents Sea Arctic, BSAr | 136 | 20–200 | 8.5±1.8 (0.2) | March, May, July | This study | 4.2 | Model | [26] |

| Barents Sea Atlantic, BSAt | 54 | 20–200 | 7.4±1.0 (0.1) | March, May, June, July | This study | 6.7 | Model | [26] |

| NW Norwegian shelf, NWNS | 73 | 20–200 | 8.6±1.6 (0.2) | April-September | This study | 6.6 | Model | [30] |

| Northeast Water Polynya, NEW | 130 | 9.2 | Annual cycle | [31] | 2.7 | [32] | ||

| North Open Water Polynya, NOW | 12 | 200–500 | 8.5±0.7 (0.2) | Annual cycle | [33] | 6.4 | NO3 inventory | [34] |

| E Greenland shelf, EGS | 20 | 245 | 9.9±1.2 (0.3) | Annual cycle | [35] | 3.3 | [32] | |

| East Beaufort Sea, EBS | 6 | 100, 200 | 9.3±1.3 (0.5) | 3 years | [36] | 1.2 | NO3 inventory | [37] |

| N Pacific subarctic gyre, K2 | 19 | 150–500 | 8.1±0.5 (0.1) | July-August | [38] | 4.0 | NO3 inventory | [39] |

| Iberian upwelling, IU | 50 | 30–200 | 8.0±0.8 (0.1) | 10 times, August | [40] | 9.3 | NO3 inventory | [41] |

| NE Atlantic subtropical gyre, ESTOC | 3 | 200–500 | 10.2 | 6 times in 2 years NP is mean of same years as CN export | [42] | 0.8 | NO3 inventory | [42] |

| N Pacific subtropical gyre, HOT | 206 | 150–500 | 10.2±0.3 | Monthly, 11 years | [9] | 1.4 | O2 prod, NP is 50% of primary production | [43] |

| NE Subarctic Pacific, OSP | 5 | 100–500 | 8.0±1.4 (0.5) | May, 5 times | [21] | 2.2 | NO3 inventory | [44] |

| W Sargasso Sea, BATS | 500 | 7.8±1.4 | 9 years, biweekly sampling | [45] | 2.5 | NO3 inventory. Conv. to C by Redfield C:N | [46] |

Statistical Analyses

Exported POC:PON data were not normally distributed wherefore regional variations and deviations from Redfield were assessed by a nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis test with the Multiple Comparisons post hoc test in Statistica® and a Wilcoxon signed rank test in R (www.r-project.org), respectively. Linearity of the POC:PON ratio was assessed by the type two regression Standard Major Axis of log-transformed POC on log-transformed PON flux using the package lmodel2 in R because the variation was uncontrolled in both directions, and to overcome the bias associated with ordinary least square regression when testing the slope against a given value (in this case 1) [12]. In log-log space, a slope equal to one implies that C and N occur in the same proportions across the whole range of C and N export values, and the SMA regression was used to test this hypothesis, following Sterner et al. (2008) [12]. Slopes were considered to be significantly different from one, indicating deviation from constancy, when the 95% confidence interval did not include the value one. The relationship between mean POC:PON and new production was assessed by a linear regression following assessments of normal distributions (Shapiro-Wilk tests, P = 0.69 and P = 0.39, respectively). The Svalbard shelf break area was excluded from the regression due to strong advection of organic matter reflective of a more southerly Atlantic production regime into this area by the West Spitsbergen Current [13], [14], material that contributes to vertical export in addition to autochthonous production.

Results and Discussion

Regional Patterns in the European Arctic Ocean

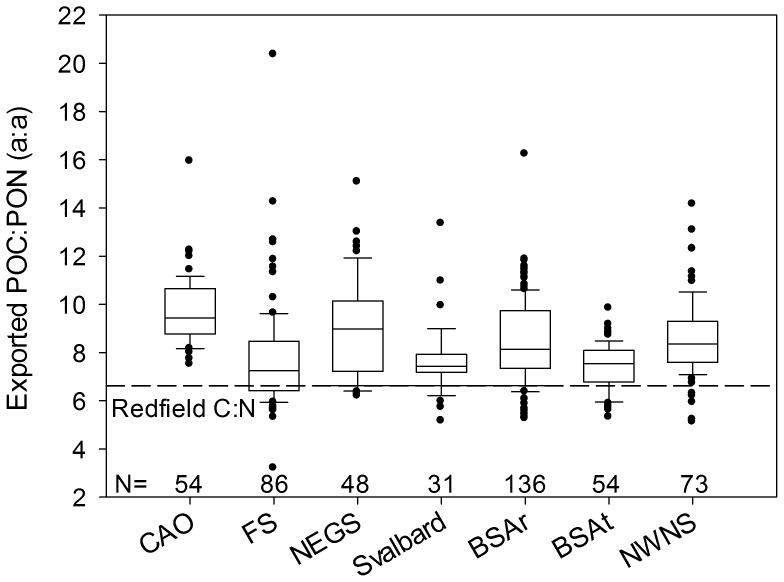

The exported POC:PON ratio increased with depth in only 8 of 61 vertical flux profiles (not shown), and comparisons are therefore based on all observations between 20 and 200 m depth. The exported POC:PON ratio was significantly different among regions (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA, P<0.0001, N = 482, Fig. 2) and was higher in the Central Arctic Ocean than elsewhere (P<0.01, Multiple Comparisons post hoc test) except over the NE Greenland shelf (P = 0.062). Variations were significant over short spatial scales relating to geophysical boundaries shown by the higher POC:PON ratio in the seasonally ice-covered northern Barents Sea than in the southern part dominated by warmer (>0°) Atlantic Water (P = 0.002). This pattern corresponds to the higher abundance of diatoms and flagellates (Phaeocystis sp.) in the phytoplankton communities of the Arctic and Atlantic sections, respectively [11]. Diatoms are exported to greater extent than Phaeocystis sp. [15] and represent a carbon-rich fraction of the exported organic matter likely owing to their high lipid content. Seasonal biases in the data, e.g. towards pre-bloom conditions in late winter in the Fram Strait and over the NE Greenland shelf and towards summer in the Central Arctic Ocean, could further increase the differences among regions.

Figure 2. Ratio between vertically exported POC and PON (a:a) in different parts of the European Arctic Ocean, with number of observations in each region.

The line indicates the median, boxes and whiskers are the 25th and 75th percentiles and 10th and 90th percentiles, respectively, and dots are outliers. The dashed line indicates the Redfield C:N ratio. Abbreviations are CAO – Central Arctic Ocean, FS – Fram Strait, NEGS – NE Greenland Shelf, Svalbard – Svalbard shelf break, BSAr – Barents Sea Arctic, BSAt – Barents Sea Atlantic, NWNS – NW Norwegian shelf.

The mean exported POC:PON was above Redfield (6.625, a:a) in all seven regions (Wilcoxon signed rank test, P<0.0001 in all cases). Conversion of nitrogen-based export estimates to POC using the Redfield ratio therefore underestimates carbon export in the European Arctic Ocean, consistent with most other oceanic regions [9]. The error is highest in the Central Arctic Ocean where the mean exported POC:PON of 9.7 implies that POC export is c. 40% (i.e. 9.7/6.6) higher than Redfield-based estimates. In order to estimate the impact of variable stoichiometry on annual POC export in the European Arctic Ocean, potential POC export was calculated by multiplying spatially integrated annual new production by the POC:PON ratio of the exported material. The potential POC export is 208 Tg C yr−1 for the entire area when using the observed POC:PON ratios specific to each region (“Observed Variable C:N”, Table 3). This is almost 30% higher than potential POC export when applying the Redfield C:N ratio (165 Tg C yr−1), and c. 10% higher than estimates based on a constant C:N ratio of 7.6 as used in the model described in Wassmann et al. 2006 [6]. Regional variations in the stoichiometry of exported organic matter therefore significantly impacts modelled POC export, and accounting for this variation is an improvement from constant stoichiometry models. However, these estimates would benefit further from more data from the Central Arctic Ocean which has relatively few observations and which also represents the largest area.

Table 3. Spatially integrated potential export of particulate organic carbon in Tg C yr−1 in the European Arctic Ocean (excluding the NW Norwegian shelf) calculated based on different C:N ratios.

| C:N ratio | ||||

| Region | Area 103 km2 | Redfield | Observed Constant | Observed Variable |

| Central Arctic Ocean | 4489a | 48.5 | 55.7 | 71.1 |

| Fram Strait | 172b | 10.4 | 11.9 | 12.2 |

| NE Greenland Shelf | 305c | 13.5 | 15.4 | 18.2 |

| Svalbard | 6a | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Barents Sea Arctic | 500d | 21.8 | 25.0 | 27.9 |

| Barents Sea Atlantic | 1012e | 70.6 | 81.0 | 79.3 |

| Total | 6484 | 164.9 | 189.2 | 208.8 |

Assessment of Linearity of Export Stoichiometry

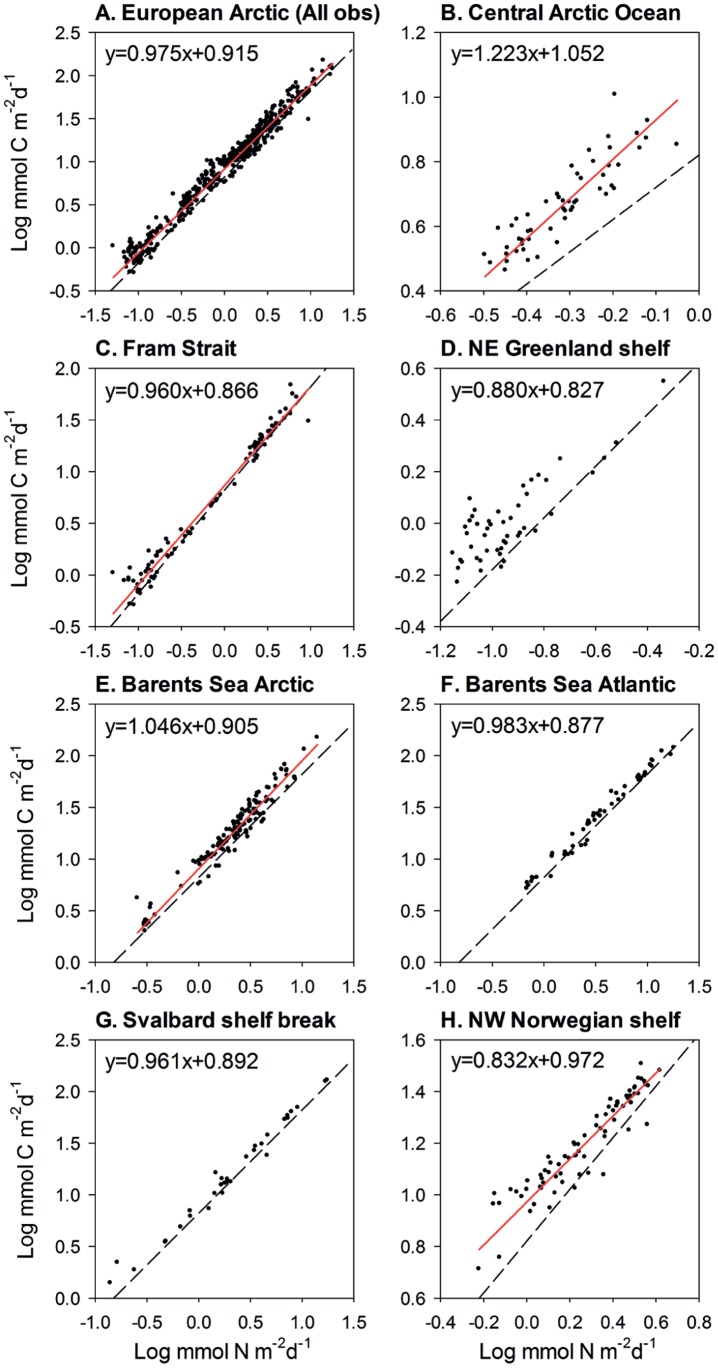

Linearity of the exported POC:PON ratio was assessed by determining the Standard Major Axis (SMA) regression of log-transformed POC flux on log-transformed PON flux, and testing the null hypothesis slope = 1 (i.e. constant ratio across the range of observed POC and PON fluxes). The SMA slope for the entire dataset was significantly smaller than one (slope = 0.975, 95% C.I. = 0.961–0.989, N = 482), implying that the POC:PON ratio is lower when the flux is high compared to when the flux is low. Hence, the POC:PON ratio decreases with increasing vertical flux (Fig. 3A, detailed regression results in Table 4). This suggests that nitrogen recycling is weaker during high-flux events corresponding to spring-bloom conditions prior to nitrogen depletion compared to low-flux events when detrital material likely comprises a larger fraction of the exported material. Among individual regions, the NW Norwegian Shelf revealed a depletion of POC relative to PON (slope = 0.832, Fig. 3H) whereas an equally strong enrichment was observed in the Central Arctic Ocean (slope = 1.22, Fig. 3B). In three regions the exported POC:PON ratio was constant (i.e. SMA slope not significantly different from one). Factors acting at regional scale therefore contribute to shaping export stoichiometry. In addition to variations in the relative contribution of dominant phytoplankton taxa (diatoms and flagellates, see above) among regions, organic matter released from sea ice represent another carbon-rich fraction of vertically exported material in ice-covered areas [16]–[18] that could partially explain the enrichemnt in POC over PON in the Central Arctic Ocean and northern Barents Sea. Colonisation of sinking particles by bacteria and heterotrophic flagellates, which was observed in a temperate upwelling system, would have an opposite effect by increasing the nitrogen content of initially nitrogen-deprived organic matter [39]. The same process could occur in the Arctic Ocean as well, but this remains speculative until more detailed data become available. In combination with dissolution and degradation of particulate organic matter, these factors contribute to shaping elemental fluxes from the water column and, therefore, to the net carbon export efficiency in terms of POC:PON stoichiometry.

Figure 3. Relationships between vertical flux of POC and PON in the European Arctic Ocean.

Log-log plots of POC on PON (log mmol m−2 d−1) and Standard Major Axis regressions based on all data (A) and for each sub-region (B–H). Regressions with slope significantly different from one are indicated by red lines. The stippled line indicates the Redfield C:N ratio. Regression coefficients with confidence intervals are given in Table 4.

Table 4. Results of Standard Major Axis regressions of log-POC flux on log-PON flux.

| Region | N | Slope | Intercept |

| European Arctic – all observations | 482 | 0.975 (0.961–0.989) | 0.915 (0.914–0.915) |

| Central Arctic Ocean | 54 | 1.223 (1.077–1.390) | 1.052 (1.007–1.104) |

| Fram Strait | 86 | 0.960 (0.927–0.993) | 0.866 (0.860–0.873) |

| NE Greenland shelf | 48 | 0.880 (0.745–1.038) | 0.827 (0.701–0.977) |

| Barents Sea Arctic | 136 | 1.046 (1.006–1.087) | 0.905 (0.892–0.918) |

| Barents Sea Atlantic | 54 | 0.983 (0.945–1.024) | 0.877 (0.855–0.898) |

| Svalbard | 31 | 0.961 (0.912–1.012) | 0.892 (0.876–0.907) |

| NW Norwegian Shelf | 73 | 0.832 (0.764–0.907) | 0.972 (0.953–0.990) |

Regression slope and intercept with 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

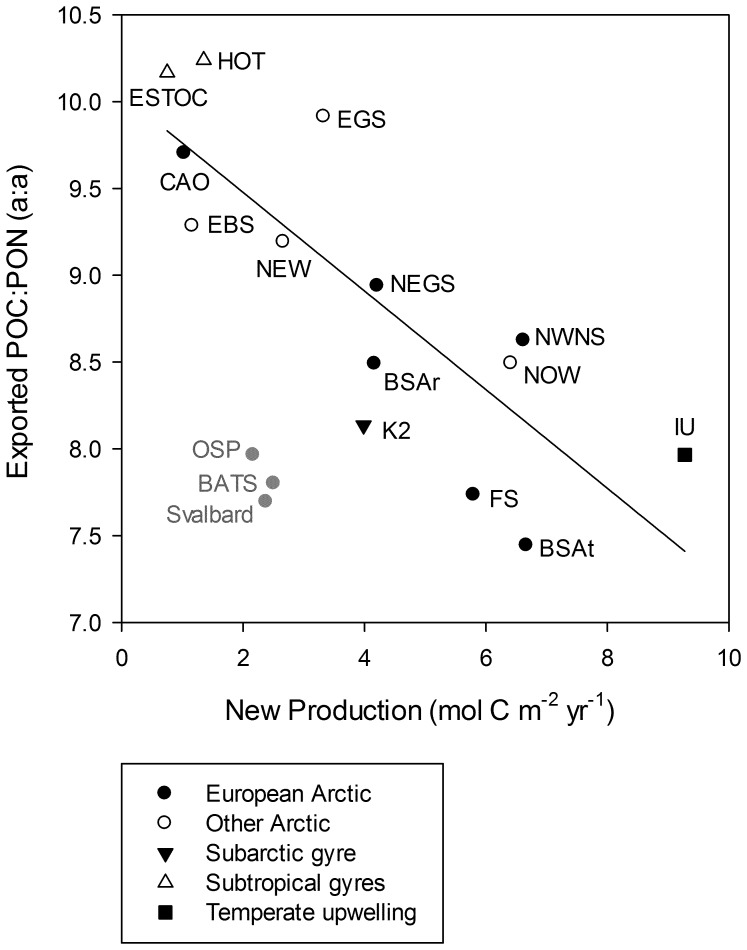

Global Patterns and Regulation of Export Stoichiometry

From a modelling point of view where regional variations in carbon export integrated over time is of primary interest, a unifying concept for regulation of export stoichiometry and, hence, carbon export efficiency, is desirable. We tested the hypotheses that nitrate-based new production is a driver of export stoichiometry across systems characterised by different trophic state (Table 2). A linear regression of the mean exported POC:PON ratio in each region on new production revealed a significant negative relationship (R2 = 0.66, P = 0.0004, Fig. 4), with exported POC:PON decreasing by 0.28 per mole carbon produced based on nitrate uptake. Standard errors of the slope and intercept were 0.0585 and 0.2811, respectively. Albeit the variation in exported POC:PON is high (range of ca 1) for any new production rate, the regression suggests stronger nitrogen recycling in nutrient-poor oligotrophic environments, resulting in higher carbon export per unit limiting nutrient as compared to more nutrient-rich mesotrophic environments. More efficient nitrogen recycling under oligotrophic regions is governed by the pelagic food web structure, which is characterized by an “inverted biomass pyramid” (i.e. heterotrophic to autorophic biomass ratio >1), resulting in consumer-control of nutrient pools and flows [19], [20]. Under eutrophic conditions where autotrophs dominate, nitrogen recycling is less efficient which again favours export of the accumulated organic matter [20]. However, even in the most productive regions the C:N ratio of exported particulate organic matter exceeds the Redfield ratio (Table 2). The observed relationship is consistent with the overall increasing proportion of PON over POC with increasing vertical flux (Fig. 3A), since the highest fluxes typically are recorded during phytoplankton blooms when new production is highest. Regions where primary production is controlled by other factors than nitrate deviate from this pattern. This is exemplified in Fig. 4 by a High Nutrient Low Chlorophyll area of the subarctic North Pacific where nitrate never is depleted in the surface layer [21], and the W Sargasso Sea where phosphorus excerts stronger control of primary production than nitrogen [22]. Hence, exceptions to what appears to be a general dependence of exported POC:PON on new production are explained by different controls of primary production in these oceanographic regions, and dominance of other phytoplankton functional groups [23]. Since nitrate limits primary production in most parts of the world’s oceans [24], nitrate-based new production emerges as a driver of export stoichiometry across climatically-defined domains (arctic, temperate, tropics).

Figure 4. Mean exported POC:PON ratio for each region against average annual new production.

The regression (y = −0.2840x+10.0450, N = 14) is significant (P = 0.0004) with an R2 of 0.66. The Svalbard shelf break was excluded from the regression due to its advective nature (see Methods). See Table 2 for abbreviations for individual sites. Regions shown for comparison but which are not included in the regression (in grey) are Svalbard, NE subarctic Pacific (OSP) and W Sargasso Sea (BATS).

Conclusions

This study shows that the C:N ratio of exported particulate organic matter is consistently above Redfield, implying that biogeochemical models based on Redfield stoichiometry underestimate POC export in the ocean. Potential POC export in the European Arctic Ocean is 10–30% higher when accounting for the variation in exported POC:PON compared to estimates based on constant stoichiometry. This study further shows that the exported POC:PON ratio varies among nitrogen-limited systems depending on new production, reflecting the system’s trophic state. Hence, the error induced by constant stoichiometry is largest in nutrient-poor oligotrophic systems, which represent the major part of the world’s oceans. Scaling export stoichiometry to trophic state improves the representation of the biological carbon pump in models, and more realistic POC export estimates are thus achieved. This is essential in order to correctly predict pathways of primary production in marine ecosystems, particularly in response to changes in inorganic nutrient supply and productivity.

Acknowledgments

We kindly acknowledge two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was financed by the Research Council of Norway (http://www.forskningsradet.no) through the project 184860/S30 MERCLIM (T.T., D.S., P.W.) and by Tromsø forskningsstiftelse through the project CONFLUX (M.R., D.S.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Dugdale RC, Goering JJ (1967) Uptake of new and regenerated forms of nitrogen in primary productivity. Limnol Oceanogr 12: 196–207. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eppley RW, Peterson BJ (1979) Particulate organic matter flux andplanktonic new production in the deep ocean. Nature 282: 677–680. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thingstad TF, Rassoulzadegan F (1995) Nutrient limitations, microbial food webs, and 'biological C-pumps': suggested interactions in a P-limited Mediterranean. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 117: 299–306. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Omta AW, Bruggeman J, Kooijman B, Dijkstra H (2009) The organic carbon pump in the Atlantic. J Sea Res 62: 179–187. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boyd PW, Trull TW (2007) Understanding the export of biogenic particles in oceanic waters: Is there consensus? Prog Oceanogr 72: 276–312. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wassmann P, Slagstad D, Riser CW, Reigstad M (2006) Modelling the ecosystem dynamics of the Barents Sea including the marginal ice zone II. Carbon flux and interannual variability. J Mar Syst 59: 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider B, Engel A, Schlitzer R (2004) Effects of depth- and CO2-dependent C : N ratios of particulate organic matter (POM) on the marine carbon cycle. Global Biogeochem Cycles 18.

- 8.Oschlies A, Schulz KG, Riebesell U, Schmittner A (2008) Simulated 21st century's increase in oceanic suboxia by CO(2)-enhanced biotic carbon export. Global Biogeochem Cycles 22.

- 9.Schneider B, Schlitzer R, Fischer G, Nöthig EM (2003) Depth-dependent elemental compositions of particulate organic matter (POM) in the ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles 17.

- 10. Coppola L, Roy-Barman M, Wassmann P, Mulsow S, Jeandel C (2002) Calibration of sediment traps and particulate organic carbon export using Th-234 in the Barents Sea. Mar Chem80: 11–26. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Olli K, Riser CW, Wassmann P, Ratkova T, Arashkevich E, et al. (2002) Seasonal variation in vertical flux of biogenic matter in the marginal ice zone and the central Barents Sea. J Mar Syst 38: 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sterner RW, Andersen T, Elser JJ, Hessen DO, Hood JM, et al. (2008) Scale-dependent carbon : nitrogen : phosphorus seston stoichiometry in marine and freshwaters. Limnol Oceanogr 53: 1169–1180. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sundfjord A, Fer I, Kasajima Y, Svendsen H (2007) Observations of turbulent mixing and hydrography in the marginal ice zone of the Barents Sea. J Geophys Res 112: C05008. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hegseth EN, Sundfjord A (2008) Intrusion and blooming of Atlantic phytoplankton species in the high Arctic. J Mar Syst 74: 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reigstad M, Wassmann P (2007) Does Phaeocystis spp. contribute significantly to vertical export of organic carbon? Biogeochemistry 83: 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meiners K, Gradinger R, Fehling J, Civitarese G, Spindler M (2003) Vertical distribution of exopolymer particles in sea ice of the Fram Strait (Arctic) during autumn. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 248: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhaskar PV, Grossart HP, Bhosle NB, Simon M (2005) Production of macroaggregates from dissolved exopolymeric substances (EPS) of bacterial and diatom origin. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 53: 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tamelander T, Reigstad M, Hop H, Ratkova T (2009) Ice algal assemblages and vertical export of organic matter from sea ice in the Barents Sea and Nansen Basin (Arctic Ocean). Polar Biol 32: 1261–1273. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gasol JM, del Giorgio PA, Duarte CM (1997) Biomass distribution in marine planktonic communities. Limnol Oceanogr 42: 1353–1363. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duarte CM, Agusti S, Gasol JM, Vaque D, Vazquez-Dominguez E (2000) Effect of nutrient supply on the biomass structure of planktonic communities: an experimental test on a Mediterranean coastal community. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 206: 87–95. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boyd PW, Sherry ND, Berges JA, Bishop JKB, Calvert SE, et al. (1999) Transformations of biogenic particulates from the pelagic to the deep ocean realm. Deep-Sea Res II 46: 2761–2792. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Babiker IS, Mohamed MAA, Komaki K, Ohta K, Kato K (2004) Temporal variations in the dissolved nutrient stocks in the surface water of the western North Atlantic Ocean. Journal of Oceanography 60: 553–562. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dutkiewicz S, Follows MJ, Bragg JG (2009) Modeling the coupling of ocean ecology and biogeochemistry. Global Biogeochem Cycles 23.

- 24.Falkowski PG, Raven JA (1997) Aquatic Photosynthesis: Blackwell Science. 375 p.

- 25. Olli K, Wassmann P, Reigstad M, Ratkova TN, Arashkevich E, et al. (2007) The fate of production in the central Arctic Ocean - Top-down regulation by zooplankton expatriates? Prog Oceanogr 72: 84–113. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reigstad M, Riser CW, Wassmann P, Ratkova T (2008) Vertical export of particulate organic carbon: Attenuation, composition and loss rates in the northern Barents Sea. Deep-Sea Res II 55: 2308–2319. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Andreassen I, Nöthig EM, Wassmann P (1996) Vertical particle flux on the shelf off northern Spitsbergen, Norway. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 137: 215–228. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tamelander T, Aubert A, Wexels Riser C (2012) Export stoichiometry and contribution of copepod faecal pellets to vertical flux of particulate organic carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 459: 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andreassen IJ, Wassmann P, Ratkova TN (1999) Seasonal variation of vertical flux of phytoplankton and biogenic matter at Nordvestbanken, north Norwegian shelf in 1994. Sarsia 84: 227–238. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Slagstad D, Tande KS, Wassmann P (1999) Modelled carbon fluxes as validated by field data on the north Norwegian shelf during the productive period in 1994. Sarsia 84: 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bauerfeind E, Garrity C, Krumbholz M, Ramseier RO, Voss M (1997) Seasonal variability of sediment trap collections in the Northeast Water Polynya.2. Biochemical and microscopic composition of sedimenting matter. J Mar Syst 10: 371–389. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sakshaug E (2004) Primary and secondary production in the Arctic Seas. In: Stein R, Mcdonald RW, editors. The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. 57–81.

- 33. Hargrave BT, Walsh ID, Murray DW (2002) Seasonal and spatial patterns in mass and organic matter sedimentation in the North Water. Deep-Sea Res II 49: 5227–5244. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tremblay JE, Gratton Y, Fauchot J, Price NM (2002) Climatic and oceanic forcing of new, net, and diatom production in the North Water. Deep-Sea Res II 49: 4927–4946. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bauerfeind E, Leipe T, Ramseier RO (2005) Sedimentation at the permanently ice-covered Greenland continental shelf (74 degrees 57.7 ' N/12 degrees 58.7 ' W): significance of biogenic and lithogenic particles in particulate matter flux. J Mar Syst 56: 151–166. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Forest A, Belanger S, Sampei M, Sasaki H, Lalande C, et al. (2010) Three-year assessment of particulate organic carbon fluxes in Amundsen Gulf (Beaufort Sea): Satellite observations and sediment trap measurements. Deep-Sea Res I 57: 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tremblay JE, Simpson K, Martin J, Miller L, Gratton Y, et al. (2008) Vertical stability and the annual dynamics of nutrients and chlorophyll fluorescence in the coastal, southeast Beaufort Sea. J Geophys Res 113: C07S90. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lamborg CH, Buesseler KO, Valdes J, Bertrand CH, Bidigare R, et al. (2008) The flux of bio- and lithogenic material associated with sinking particles in the mesopelagic "twilight zone" of the northwest and North Central Pacific Ocean. Deep-Sea Res II 55: 1540–1563. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kawakami H, Honda MC, Wakita M, Watanabe S (2007) Time-series observation of dissolved inorganic carbon and nutrients in the northwestern north pacific. Journal of Oceanography 63: 967–982. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Olli K, Riser CW, Wassmann P, Ratkova T, Arashkevich E, et al. (2001) Vertical flux of biogenic matter during a Lagrangian study off the NW Spanish continental margin. Prog Oceanogr 51: 443–466. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Alvarez-Salgado XA, Beloso S, Joint I, Nogueira E, Chou L, et al. (2002) New production of the NW Iberian shelf during the upwelling season over the period 1982–1999. Deep-Sea Res I 49: 1725–1739. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Neuer S, Cianca A, Helmke P, Freudenthal T, Davenport R, et al. (2007) Biogeochemistry and hydrography in the eastern subtropical North Atlantic gyre. Results from the European time-series station ESTOC. Prog Oceanogr 72: 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Emerson S, Quay P, Karl D, Winn C, Tupas L, et al. (1997) Experimental determination of the organic carbon flux from open-ocean surface waters. Nature 389: 951–954. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wong CS, Waser NAD, Whitney FA, Johnson WK, Page JS (2002) Time-series study of the biogeochemistry of the North East subarctic Pacific: reconciliation of the C(org)/N remineralization and uptake ratios with the Redfield ratios. Deep-Sea Res II 49: 5717–5738. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Conte MH, Ralph N, Ross EH (2001) Seasonal and interannual variability in deep ocean particle fluxes at the Oceanic Flux Program (OFP)/Bermuda Atlantic Time Series (BATS) site in the western Sargasso Sea near Bermuda. Deep-Sea Res II 48: 1471–1505. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cianca A, Helmke P, Mourino B, Rueda MJ, Llinas O, et al. (2007) Decadal analysis of hydrography and in situ nutrient budgets in the western and eastern North Atlantic subtropical gyre. J Geophys Res 112: C07025. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jakobsson M, Grantz A, Kristoffersen Y, Macnab R (2004) The Arctic Ocean: Boundary Conditiona and Background Information. In: Stein R, Macdonald RW, editors. The Organic Carbon Cycle in the Arctic Ocean. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. 1–32.

- 48. Ellingsen I, Slagstad D, Sundfjord A (2009) Modification of water masses in the Barents Sea and its coupling to ice dynamics: a model study. Ocean Dynamics 59: 1095–1108. [Google Scholar]