Abstract

Aims

To estimate age-period-cohort models predicting alcohol volume, heavy drinking and beverage-specific alcohol volume in order to evaluate whether the 1976–1985 birth cohorts drink relatively heavily.

Design

Data from seven cross-sectional surveys of the US conducted between 1979 and 2010 were utilized in negative binomial generalized linear models of age, period and cohort effects predicting alcohol measures.

Setting

General population surveys of the US.

Participants

36,432 US adults (aged 18 or older).

Measurements

Monthly number of alcohol drinks, beer, wine and spirits drinks and days drinking 5 or more drinks in the past year derived from beverage-specific graduated frequency questions.

Findings

Relative to the reference 1956–60 birth cohort, men in the 1976–1980 cohort for were found to consume more alcohol (Incidence rate ratio (IRR) =1.222: CI 1.07–1.39) and to have more 5+ days (IRR=1.365: CI 1.09–1.71) as were men in the 1980–85 cohort for volume (IRR=1.284: CI 1.10–1.50) and 5+ days (IRR=1.437: CI 1.09–1.89). For women, those in the 1980–85 cohort were found to have higher alcohol volume (IRR=1.299: CI 1.07–1.58) and more 5+ days (IRR=1.547: CI 1.01–2.36). Beverage-specific models found different age patterns of volume by beverage with a flat age pattern for both genders’ spirits and women’s wine, an increasing age pattern for men’s wine and a declining age pattern from the early 20’s for beer.

Conclusions

In the United States, men born between 1976 and 1985, and women born between 1981 and 1985 have higher alcohol consumption than in earlier or later years.

Keywords: Cohort, beer, wine, spirits, alcohol use, trends, age

INTRODUCTION

The 20th century peak of per capita apparent alcohol consumption in the United States (US) occurred in 1980 and 1981 at 10.45 liters of ethanol. A sharp drop began in 1982 and consumption ultimately declined by 22.5% through 1997. Per capita consumption then rose slowly from 1998, increasing by 8.4% through 2008. [1] Spirits accounted for more than half of the decline in consumption through 1997 and beer for about a third, with the remainder from wine. Per capita beer consumption has been remarkably flat since and the increase since 1998 has come roughly equally from spirits and wine. In the context of rising per capita spirits, wine and total consumption it is essential to understand details of the underlying dynamics of change in order to identify groups at elevated risk for current and future alcohol-related harms.

Age-period-cohort (APC) analysis offers a framework for disentangling changes over time by assuming separable influences of aging, birth cohort and time period and allowing control of additional influences such as socio-demographic measures. The National Alcohol Surveys (NAS) are a series of approximately 5-yearly US general population surveys focused on alcohol consumption patterns and alcohol-related problems, conducted using comparable questions since 1979. The extended time period and even spacing of the seven surveys make this series well suited for APC analyses focused on the determinants of trends in alcohol consumption and drinking patterns over the past 30 years.

The NAS series through 2000 has been utilized in previous APC analyses of alcohol volume by beverage type [2] and cannabis use. [3] The beverage-specific APC analyses found declining age effects for beer and spirits but not wine, positive cohort effects for spirits in the pre-1945 birth cohorts for both men and women and positive cohort effects for beer among men in the baby boom cohorts while beer cohort effects for women were highest in the oldest cohorts. Results also indicated that the declining trend in spirits consumption was mainly due to cohort effects while the decline in beer was mainly due to period effects. Because present analyses utilize two additional surveys over the subsequent 10 years, they should result in more stable estimates of APC effects, especially for the younger birth cohorts. A further analysis of alcohol volume and heavy occasion drinking [4] utilized the NAS surveys through 2005. Results suggested a potential birth cohort effect with higher levels of alcohol volume and heavy drinking occasions for both men and women born between 1976 and 1985 than for other cohorts. A positive cohort effect for women was also found for the 1956–60 birth cohort. This result was consistent with a finding that the late baby boom cohort of women (born 1957–63) had higher lifetime odds of alcohol dependence in the NLAES and NESARC samples. [5] Because the 1976–85 cohorts were only observed in the youngest age groups in the 1995, 2000 and 2005 NAS surveys, the addition of data from 2010, where these cohorts are in their late 20’s and early 30’s, should provide a more conclusive test of the hypothesis that these cohorts drink more heavily. The present study updates earlier analyses by adding the 2010 survey and includes analyses of beverage-specific alcohol volume to develop further understanding of factors influencing beverage choice and the role of different beverage types in overall trends, birth cohort differences and age or maturational patterns. We also provide some specific hypotheses regarding potential sources of recent cohort differences.

METHODS

Surveys

Data used in all analyses come from seven National Alcohol Surveys conducted for the Alcohol Research Group’s National Alcohol Research Center between 1979 and 2010. Details for each survey are presented in Table 1. Major differences between surveys are over-sampling of Hispanics and African Americans in all but two surveys (1979 and 1990) and a mode switch from face-to-face interviews with multi-stage clustered sampling to telephone interviews and random-digit dialed sampling in 2000. The 2010 NAS also included a mobile phone sample. All surveys are weighted to the general population of the US at the time they were conducted taking account of age, sex, ethnic group and geographic area.

Table 1.

Design Characteristics of the National Alcohol Survey (NAS) Cross-Sectional Series and Key Methodological Sub-studies

| Survey Characteristic | NAS Survey Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 1984 | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | |

| N | 1,772 | 5,221 | 2,058 | 4,925 | 7,612 | 6,919 | 7,969 |

| Resonse Rate | 71% | 72% | 70% | 77% | 58% | 56% | 52% |

| Sampling Design | Muti-stage clustered | Muti-stage clustered | Muti-stage clustered | Muti-stage clustered | List-Assisted RDD | List-Assisted RDD | List-Assisted RDD |

| Sampling Frame | 48 Contiguous States | 48 Contiguous States | 48 Contiguous States | 48 Contiguous States | 50 States plus Washington | 50 States plus Washington | 50 States plus Washington |

| Interview Mode | In-person | In-person | In-person | In-person | Telephone | Telephone | Telephone |

| African American & Hispanic Oversamples? | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Small States Augmented? | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fieldwork Organization | Response Analysis Corp. | Temple Univ., Inst. Social Res. | Temple Univ., Inst. Social Res. | Temple Univ., Inst. Social Res. | Temple Univ., Inst. Social Res. | Data Stat, Inc. | ICF Macro, Inc. |

Note: Contiguous States Omit Alaska and Hawaii; Telephone Response Rates are APOR 3 Cooperation Rate

Extensive methodological work on interview modes found no significant difference in national estimates of mean alcohol intake based on modality of interviewing, even though response rates of the telephone surveys were lower than the in-person ones. [6, 7] Within-subjects interview modality analyses of the 1995 NAS data [7] also evaluated the number of 5+ days and found significantly more reported 5+ days in the face-to-face survey. However, further analyses determined that the difference occurred among those reporting less than monthly 5+ frequency. Any general interview mode effect would appear as a period effect in the analyses because these capture methodological changes over time as well as secular drift. Therefore, methodological differences should not bias the age and cohort coefficients unless the mode effect differed along these dimensions as well. The lower response rates seen in the most recent surveys are consistent with the general decline in response rates across all types of surveys. [8] Declines in response rates of similar magnitude have been shown to have little impact on results [9] in a methodological comparison.

Measures

Responses to questions on the beverage-specific frequency of drinking are used to estimate the number of days each beverage type was drunk in the prior 12 months. For each beverage type, respondents were then asked: “When you drink (wine/ beer/ drinks containing whiskey or liquor), how often do you have 1–2, 3–4, or as many as five or six (glasses/ 12-ounce cans or bottles /drinks)?” Answer categories included ‘nearly every time’, ‘more than half the time’, ‘less than half the time’, ‘once in a while’ and ‘never’, which were coded as 0.9, 0.7, 0.3, 0.1 and 0, respectively in a standard volume algorithm. The number of 5+ days was calculated conservatively as the sum of 5+ days for each beverage with a maximum of 365 days per year.

Race and ethnic groups were created for white (non-Hispanic) Asian, African American (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, Native American and all others. Educational attainment was coded as less than high school, high school graduate only, some college and college graduate or higher. Marital status was coded as married, widowed, divorced or separated and never married. Religion was coded as Catholic, “no religion” and all others based on preliminary analyses. Employment status was categorized into three groups: unemployed, retired and all others including employed. Income was converted to 2005 dollars using the mid-point of the categories asked in each survey year and then re-categorized into $0–20,000, $20,000 to 40,000, $40,000 to 70,000 and $70,000 or more, and income missing. State groupings by “wetness” were created based partly on geographic proximity but primarily on the estimates of heavy occasion drinking from the NSDUH 2005–2006 combined sample and 2005 state-level per capita apparent consumption of alcohol. [10] Resulting groups in a six-level categorization are the Wet state groups of New England and the North Central states, Moderate state groups of the Middle Atlantic, Pacific Coast and South Coast states and the Dry state group of mostly Southern states.

Variables representing contiguous groups were created for age, period and cohort. Age was categorized into 8 groups starting from 18–20 and then in 5-year groups for 21–25 and 26–30 and then in 10-year groups from 31–40 through 61–70 with an oldest group of 71 and older. Period was represented by an indicator for each survey year. Cohort was defined by birth year in 16 mostly 5-year groups after a larger group born in 1900–1920, i.e. from 1921–25 through 1986–90 and ending with a smaller 1991–1992 group (aged 18–19 in 2010).

Analyses

Separate models were estimated for men and women. Samples included 20,732 women and 15,700 men. Models provide estimates of age, period and cohort effects, which are assumed to be independent, controlling for key measured characteristics known to be related to drinking. [11] Negative binomial generalized linear models of the natural logarithm of alcohol volume and the number of days having five or more drinks (5+) in the past year were estimated in Stata version 10 using pseudo-maximum likelihood methods modified to account for sample weights, which sum to the sample size in each survey and take account of the stratified design in the earlier surveys. [12] We did not utilize the cross-classified random effects model [13] because implementations of this model do not allow for standard errors to be adjusted for complex survey design effects. The number of surveys may also be too low for efficient random effects estimation. We did estimate linear regression random effects models of alcohol volume without weights or design effects and found a similar pattern of cohort effects to those presented. Results are presented in terms of exponentiated coefficients known as the incidence rate ratio (IRR). As in our previous analyses, [4] the need for broader age and cohort groups for older respondents where heavy drinking is rare and the inclusion of socio-demographic control variables ensure identification of the models, which was confirmed through principal components analysis. [14] The condition number of 0.112 indicates that there is not a problem with identification.

RESULTS

The results of age, period and cohort decompositions from gender-specific models including key socio-demographic predictors of overall alcohol volume, 5+ days in the past year are presented in Tables 2 and 3, while results for beer, spirits and wine volumes are presented in sets of figures for each outcome measure. All models also included a range of socio-demographic variables and the results for these in the volume and 5+ days models are presented in Tables 1 and 2 but are not shown for the beverage-specific models. Trends through 2005 in alcohol volume and 5+ drinking days were presented in our earlier study [4]. Small increases in volume and 5+ days were seen for both men and women from 2005 to 2010 with this increase occurring mainly in spirits for women and beer for men.

Table 2.

Estimated age, period and cohort effects on total alcohol volume displayed as incidence rate ratios (IRR) from negative binomial generalized linear models controlling for individual socio-demographic characteristics with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

| Year | Men IRR |

95% | CI | Women IRR |

95% | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 1.298* | 1.12 | 1.51 | 1.265* | 1.07 | 1.50 | |

| 1984 | 1.382* | 1.21 | 1.57 | 1.357* | 1.17 | 1.57 | |

| 1990 | 1.072 | 0.95 | 1.20 | 1.059 | 0.93 | 1.21 | |

| 1995 | 1.104* | 1.01 | 1.21 | 1.082 | 0.97 | 1.21 | |

| 2000 | 0.948 | 0.88 | 1.02 | 0.921 | 0.85 | 1.00 | |

| 2005 | 0.981 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 1.028 | 0.96 | 1.10 | |

| 2010 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Age | |||||||

| 18–20 | 0.901 | 0.76 | 1.06 | 0.867 | 0.72 | 1.04 | |

| 21–25 | 1.205* | 1.07 | 1.36 | 1.260* | 1.09 | 1.46 | |

| 26–30 | 1.086 | 0.98 | 1.20 | 1.125 | 0.99 | 1.27 | |

| 31–40 | 1.069 | 1.00 | 1.15 | 1.082 | 0.99 | 1.18 | |

| 41–50 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 51–60 | 0.963 | 0.89 | 1.04 | 1.019 | 0.94 | 1.11 | |

| 61–70 | 0.969 | 0.85 | 1.11 | 0.982 | 0.86 | 1.12 | |

| 71plus | 0.880 | 0.72 | 1.08 | 0.841 | 0.70 | 1.02 | |

| Birth Cohort | |||||||

| 1900–20 | 0.770 | 0.62 | 0.96 | 0.796 | 0.62 | 1.02 | |

| 1921–25 | 0.943 | 0.78 | 1.15 | 0.784 | 0.63 | 0.98 | |

| 1926–30 | 0.958 | 0.78 | 1.17 | 0.819 | 0.66 | 1.01 | |

| 1931–35 | 0.977 | 0.84 | 1.14 | 0.865 | 0.74 | 1.02 | |

| 1936–40 | 1.008 | 0.88 | 1.15 | 0.873 | 0.75 | 1.01 | |

| 1941–45 | 0.906 | 0.81 | 1.01 | 0.845 | 0.75 | 0.95 | |

| 1946–50 | 1.004 | 0.93 | 1.09 | 0.936 | 0.85 | 1.03 | |

| 1951–55 | 0.977 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 0.892 | 0.82 | 0.98 | |

| 1956–60 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 1961–65 | 1.064 | 0.99 | 1.15 | 1.021 | 0.93 | 1.12 | |

| 1966–70 | 1.052 | 0.96 | 1.15 | 0.983 | 0.88 | 1.10 | |

| 1971–75 | 1.126* | 1.01 | 1.26 | 0.955 | 0.84 | 1.09 | |

| 1976–80 | 1.222* | 1.07 | 1.39 | 1.088 | 0.94 | 1.26 | |

| 1981–85 | 1.284* | 1.10 | 1.50 | 1.299* | 1.07 | 1.58 | |

| 1986–90 | 1.171 | 0.96 | 1.43 | 0.936 | 0.73 | 1.20 | |

| 1991–92 | 1.268 | 0.64 | 2.50 | 1.004 | 0.51 | 1.99 | |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Income <20k | 0.898* | 0.84 | 0.96 | 0.784* | 0.73 | 0.85 | |

| 20K to 40k | 0.932* | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.926* | 0.03 | 0.99 | |

| 40k to70k | 1.000 | ||||||

| 70k+ | 1.159* | 1.11 | 1.22 | 1.214* | 1.14 | 1.29 | |

| White | 1.000 | ||||||

| Asian | 0.641* | 0.56 | 0.73 | 0.578* | 0.47 | 0.70 | |

| Black | 0.901* | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.782* | 0.73 | 0.84 | |

| Hispanic | 0.795* | 0.74 | 0.85 | 0.580* | 0.53 | 0.63 | |

| Am Indian | 0.859 | 0.71 | 1.04 | 0.886 | 0.71 | 1.10 | |

| Other Eth. | 0.934* | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.938 | 0.88 | 1.00 | |

| <HS | 0.901* | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.766* | 0.70 | 0.84 | |

| High School | 1.000 | ||||||

| Some Col | 1.040 | 0.99 | 1.09 | 1.196* | 1.13 | 1.27 | |

| College+ | 1.113 | 1.06 | 1.17 | 1.357* | 1.28 | 1.44 | |

| Married | 1.000 | ||||||

| Divorce/Sep | 1.212 | 1.13 | 1.30 | 1.283* | 1.20 | 1.37 | |

| Widowed | 1.109 | 0.97 | 1.27 | 0.902 | 0.81 | 1.00 | |

| Never Mar | 1.046 | 0.99 | 1.11 | 1.284* | 1.20 | 1.37 | |

| N Central | 1.044 | 0.99 | 1.10 | 0.994 | 0.93 | 1.06 | |

| New England | 1.057 | 0.98 | 1.14 | 1.026 | 0.93 | 1.13 | |

| Mid Atlantic | 1.000 | ||||||

| Pacific | 1.022 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 1.049 | 0.97 | 1.13 | |

| South Coast | 1.016 | 0.95 | 1.08 | 0.895* | 0.83 | 0.97 | |

| Dry South | 0.832* | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.739* | 0.68 | 0.81 | |

| Other religion | 1.000 | ||||||

| Catholic | 1.380* | 1.32 | 1.44 | 1.393* | 1.33 | 1.46 | |

| No religion | 1.333* | 1.27 | 1.40 | 1.494* | 1.40 | 1.60 | |

| Employed | 1.000 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1.019 | 0.93 | 1.12 | 1.193* | 1.07 | 1.33 | |

| Retired | 0.957 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 1.084 | 0.98 | 1.20 | |

Indicates significance at the 95% confidence level.

Table 3.

Estimated age, period and cohort effects on the number of days having 5 or more drinks displayed as incidence rate ratios (IRR) from negative binomial generalized linear models controlling for individual socio-demographic characteristics with 95% confidence intervals.

| Year | Men IRR |

95% | CI | Women IRR |

95% | CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 1.337* | 1.00 | 1.78 | 1.207 | 0.80 | 1.83 | |

| 1984 | 1.536* | 1.20 | 1.97 | 1.445 | 1.00 | 2.09 | |

| 1990 | 1.199 | 0.98 | 1.47 | 1.205 | 0.88 | 1.65 | |

| 1995 | 1.079 | 0.91 | 1.28 | 1.017 | 0.78 | 1.33 | |

| 2000 | 0.919 | 0.81 | 1.04 | 0.859 | 0.70 | 1.05 | |

| 2005 | 0.962 | 0.86 | 1.07 | 1.044 | 0.88 | 1.24 | |

| 2010 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Age | |||||||

| 18–20 | 0.967 | 0.73 | 1.27 | 1.064 | 0.70 | 1.62 | |

| 21–25 | 1.441* | 1.16 | 1.79 | 1.511* | 1.08 | 2.12 | |

| 26–30 | 1.207* | 1.01 | 1.45 | 1.508* | 1.13 | 2.02 | |

| 31–40 | 1.206* | 1.06 | 1.37 | 1.399* | 1.14 | 1.72 | |

| 41–50 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 51–60 | 0.817* | 0.70 | 0.95 | 0.723* | 0.57 | 0.91 | |

| 61–70 | 0.633* | 0.49 | 0.82 | 0.570* | 0.39 | 0.83 | |

| 71plus | 0.405* | 0.25 | 0.65 | 0.381* | 0.21 | 0.68 | |

| Birth Cohort | |||||||

| 1900–20 | 0.373* | 0.23 | 0.61 | 0.316* | 0.15 | 0.66 | |

| 1921–25 | 0.874 | 0.59 | 1.31 | 0.391* | 0.21 | 0.73 | |

| 1926–30 | 0.794 | 0.54 | 1.16 | 0.600 | 0.34 | 1.05 | |

| 1931–35 | 0.854 | 0.63 | 1.16 | 0.617* | 0.40 | 0.95 | |

| 1936–40 | 0.941 | 0.73 | 1.21 | 0.651* | 0.44 | 0.97 | |

| 1941–45 | 0.798* | 0.65 | 0.98 | 0.655* | 0.49 | 0.88 | |

| 1946–50 | 0.943 | 0.81 | 1.09 | 0.841 | 0.66 | 1.08 | |

| 1951–55 | 0.968 | 0.85 | 1.10 | 0.844 | 0.69 | 1.04 | |

| 1956–60 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 1961–65 | 1.040 | 0.91 | 1.19 | 0.864 | 0.70 | 1.06 | |

| 1966–70 | 1.067 | 0.91 | 1.25 | 0.942 | 0.74 | 1.20 | |

| 1971–75 | 1.189 | 0.98 | 1.43 | 0.860 | 0.65 | 1.14 | |

| 1976–80 | 1.365* | 1.09 | 1.71 | 1.205 | 0.86 | 1.69 | |

| 1981–85 | 1.437* | 1.09 | 1.89 | 1.547* | 1.01 | 2.36 | |

| 1986–90 | 1.258 | 0.90 | 1.76 | 0.920 | 0.55 | 1.54 | |

| 1991–92 | 1.569 | 0.71 | 3.46 | 0.501 | 0.17 | 1.47 | |

| Covariates | |||||||

| Income <20k | 0.986 | 0.89 | 1.09 | 1.060 | 0.90 | 1.25 | |

| 20K to 40k | 1.016 | 0.05 | 1.11 | 1.080 | 0.09 | 1.26 | |

| 40k to70k | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 70k+ | 1.089 | 0.99 | 1.19 | 1.162 | 0.99 | 1.37 | |

| White | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Asian | 0.547* | 0.43 | 0.70 | 0.361* | 0.24 | 0.55 | |

| Black | 0.849* | 0.77 | 0.94 | 0.765* | 0.66 | 0.88 | |

| Hispanic | 0.779* | 0.70 | 0.87 | 0.527* | 0.44 | 0.63 | |

| Am Indian | 1.012 | 0.74 | 1.39 | 1.189 | 0.83 | 1.70 | |

| Other Eth. | 0.913* | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.975 | 0.87 | 1.09 | |

| <HS | 0.981 | 0.88 | 1.10 | 0.942 | 0.79 | 1.13 | |

| High School | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Some Col | 0.962 | 0.88 | 1.05 | 0.964 | 0.84 | 1.10 | |

| College+ | 0.821* | 0.75 | 0.90 | 0.948 | 0.81 | 1.10 | |

| Married | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Divorce/Sep | 1.461* | 1.31 | 1.63 | 1.502* | 1.30 | 1.74 | |

| Widowed | 1.177 | 0.86 | 1.60 | 0.939 | 0.69 | 1.28 | |

| Never Mar | 1.146* | 1.05 | 1.25 | 1.660* | 1.45 | 1.90 | |

| N Central | 1.153* | 1.04 | 1.28 | 1.074 | 0.91 | 1.26 | |

| New England | 1.029 | 0.87 | 1.22 | 0.860 | 0.64 | 1.16 | |

| Mid Atlantic | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Pacific | 0.983 | 0.87 | 1.11 | 1.117 | 0.91 | 1.36 | |

| South Coast | 1.085 | 0.97 | 1.22 | 0.894 | 0.73 | 1.09 | |

| Dry South | 0.863* | 0.77 | 0.97 | 0.749 | 0.62 | 0.90 | |

| Other religion | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Catholic | 1.549* | 1.43 | 1.68 | 1.589* | 1.41 | 1.79 | |

| No religion | 1.546* | 1.42 | 1.69 | 1.884* | 1.64 | 2.17 | |

| Employed | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| Unemployed | 1.073 | 0.94 | 1.23 | 1.408* | 1.16 | 1.71 | |

| Retired | 0.832 | 0.68 | 1.03 | 1.089 | 0.78 | 1.52 | |

Indicates significance at the 95% confidence level.

Overall alcohol volume and 5+ days in the past year

Results for alcohol volume are presented in Table 2. Compared to those aged 41–50, only those aged 21–25 are found to have significantly higher alcohol intake volume. Period effect results show that the 1979 and 1984 surveys (during the period of highest per capita consumption) had higher volumes than later surveys. Cohort effect estimates indicate that the 1976 to 1980 birth cohort for men, and the 1981–85 birth cohort for both men and women, showed significantly higher alcohol volume than the reference 1956–60 birth cohort. Cohorts with significantly lower alcohol volume were the 1900–1920 cohort for men and the 1921–25, 1941–45 and 1951–55 birth cohorts for women.

Results for days drinking five or more drinks are presented in Table 3. Age effects were more pronounced than those for alcohol volume with significantly higher IRR’s in the ages 21–40 groups and significantly lower IRR’s in the 51 and older groups for both men and women. Period effects again showed the 1979 and 1984 surveys to be higher for men but no significant differences were found for women. Birth cohort effects for 5+ days were of greater magnitude than those for alcohol volume but occurred in the same cohorts for men with higher IRR’s in the 1976–85 cohorts and lower IRR’s in the 1900–1920 cohort as well as in the 1941–45 cohort. For women, higher IRR’s for 5+ days were seen in the 1981–85 cohort, as was the case for alcohol volume, and lower IRR’s in the 1900–1920, 1921–25, 1931–35, 1936–40 and 1941–45 cohorts. For women the IRR’s for 5+ drinking were below one in all cohorts except the 1976–80 and 1981–85 groups suggesting that the reference 1956–60 birth cohort is itself a relatively high heavy-occasion drinking group.

Volume of beer, wine and spirits

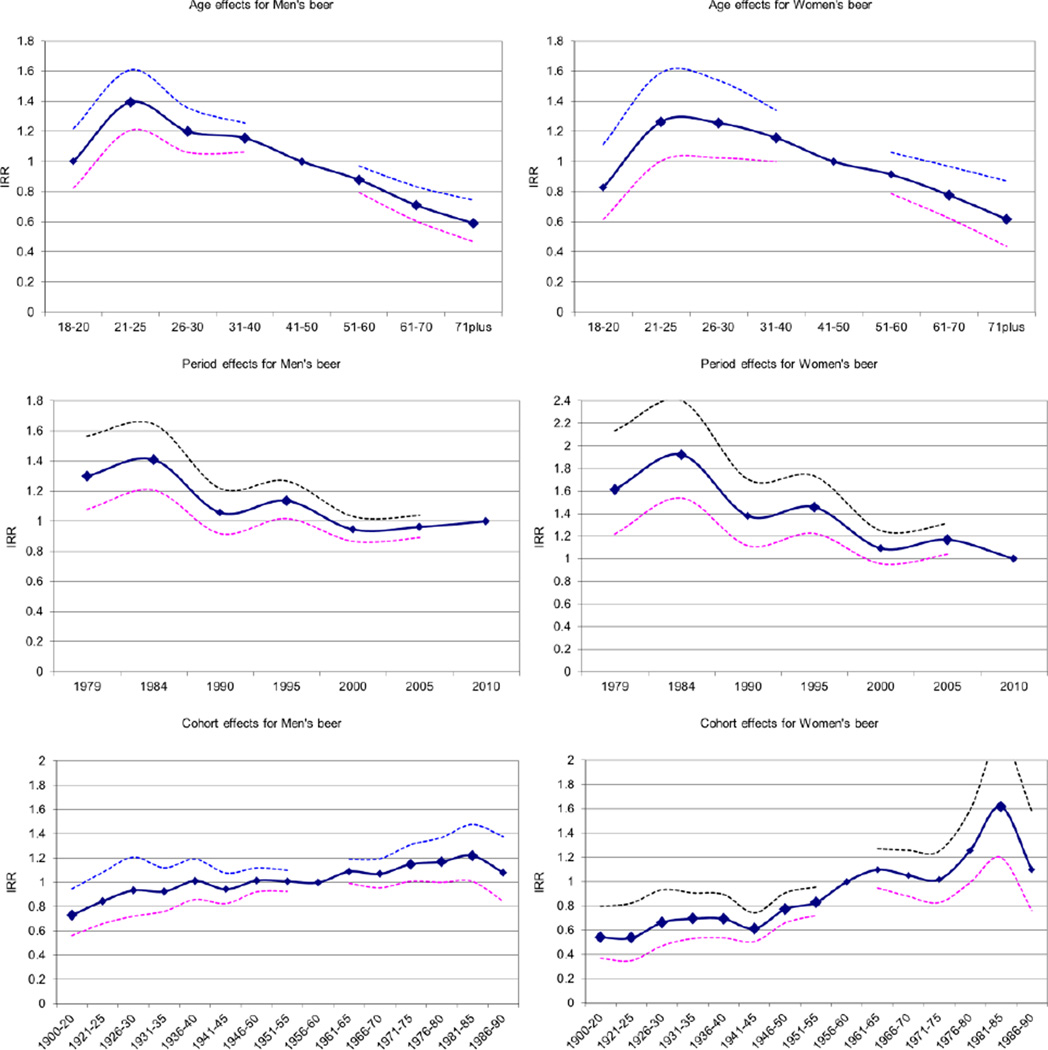

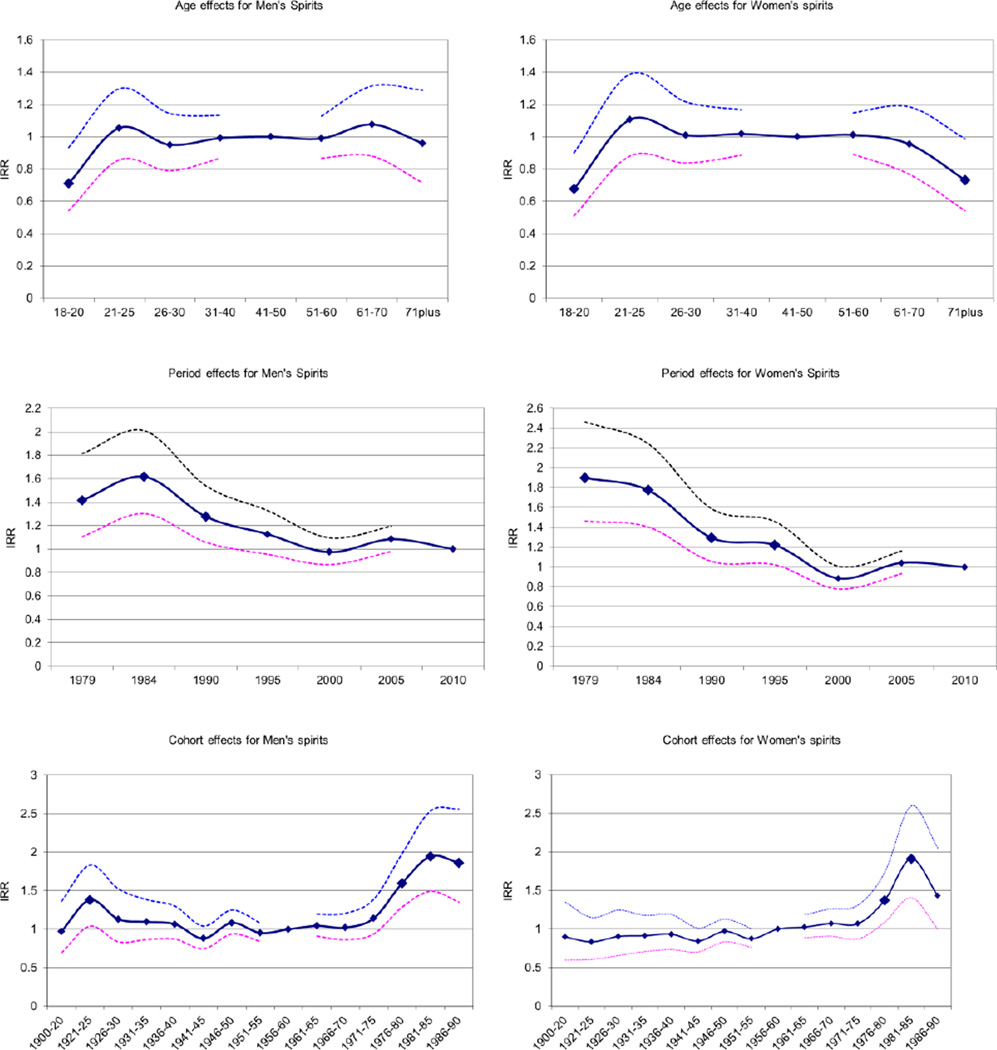

Age, period and cohort effects in the beverage-specific models are presented in Figures 1, 2 and 3. Coefficients for the 1991–92 cohort group are not presented due to wide confidence intervals but are estimated in each model. Beer is clearly the preferred beverage at younger ages (peaking at 21–25), but period effects show the overall decline in consumption through 2000. Cohort effects are generally increasing in more recent cohorts but are small for men. Stronger cohort effects are seen for women with significantly lower beer consumption seen in cohorts before 1955 and particularly high beer consumption in the 1981–85 cohort. Spirits consumption experienced the most pronounced decline over the past decades. Spirits consumption was also found to be the least dependent on age with an almost flat maturation profile. Recent cohorts for both men and women are found to have large positive cohort effects for spirits. Period and cohort effects for wine consumption have been relatively stable over the past decades, although an increasing pattern of cohort effects was found men. Age effect estimates for wine indicate increased consumption with age for men while a flat profile was seen for women.

Figure 1.

Estimated age, period and cohort effects on the volume of beer displayed as incidence rate ratios (IRR) from negative binomial generalized linear models controlling for individual socio-demographic characteristics. Reference groups are the 41–50 age group, the 2010 survey and the 1956–1960 birth cohort. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals and large diamonds indicate a significant difference from the reference group.

Figure 2.

Estimated age, period and cohort effects on the volume of spirits displayed as incidence rate ratios (IRR) from negative binomial generalized linear models controlling for individual socio-demographic characteristics. Reference groups are the 41–50 age group, the 2010 survey and the 1956–1960 birth cohort. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals and large diamonds indicate a significant difference from the reference group.

Figure 3.

Estimated age, period and cohort effects on the volume of wine displayed as incidence rate ratios (IRR) from negative binomial generalized linear models controlling for individual socio-demographic characteristics. Reference groups are the 41–50 age group, the 2010 survey and the 1956–1960 birth cohort. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence intervals and large diamonds indicate a significant difference from the reference group.

DISCUSSION

Results suggest a birth cohort effect with heavier drinking in the 1976–1985 birth cohorts. For women, the narrower 1981–85 birth cohort stands out especially. Additionally for women, the 1956–60 cohort is higher for heavy occasion drinking. Period effects show a substantial decline in the late 1980’s. Recent cohorts show a relative preference for spirits and wine. Age effects typically peak in the early 20’s, then decline. This pattern appears to result from beer only. Wine and spirits have relatively flat age profiles. It is especially important to try to understand characteristics of the 1976–1985 birth cohorts, and the conditions between 1995 and 2005 when their drinking habits were being developed, that could account for the estimated positive cohort effects.

One hypothesis for explaining recent birth cohort effects is the affordability of alcohol in terms of real prices and the unemployment rates and real incomes of young people. Real prices had declined substantially from the 1950’s through the mid 1980’s. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Alcohol Consumer Price Index (CPI) converted to 2011 dollars with the overall CPI was 165.5 in 1950, 145.27 in 1960 and around 100 since the early 1980’s indicating flat real prices at a low level over the past 30 years. Our calculations for the lowest cost vodka or gin in Pennsylvania converted to 2011 dollars indicates an even more substantial decline in the real cost of the cheapest alcohol option for a US standard drink (14g ethanol) from $1.58 in 1950 to $1.50 in 1960, $0.41 in 1995, $0.36 in 2000 and to $0.29 in 2011. [15–19] The BLS Alcohol CPI includes all beverage types and on- as well of off-premise prices, which did not decline as much as spirits prices or off-premise prices in general. Most relevant to the economic explanation of the estimated cohort effects is that the employment outlook for young people was especially good during the late 1990’s with unemployment rates for those aged 16–24 declining from 12.6% in the 3rd quarter of 1995 to 9.1% in the 4th quarter of 2000 according to data from the Current Population Survey. Good economic conditions, which tend to increase social drinking [20, 21], ended with the 2008–9 recession when unemployment for those 16–24 rose to 14.2% in late 2008 and then to 19% in late 2009, staying above 18% through 2010. We hypothesize that the good employment and income situation for young people in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, in contrast to earlier and later cohorts, led to heavier drinking patterns.

A second key factor underlying the positive effects for spirits in recent birth cohorts may have been increased television advertising of spirits brands with the expansion of cable and satellite television. Television advertising spending on spirits increased from $1.4 million in 1995 to $25 in 2000, $82 million in 2004 and to $150 million in 2009. [22, 23] A recent study has also documented the importance of targeted marketing efforts around co-branded flavored malt beverages (FMBs) and spirits, especially Smirnoff Ice and Smirnoff vodka. [24] Beginning in 2000 Smirnoff Ice and other FMBs, drinks appealing mostly to younger women, were heavily marketed on US television and through other media. The 1981–85 birth cohort were aged 16–20 in 2001 and so this group was beginning to drink regularly during the period of heaviest marketing for FMBs. Mosher [24] argues that the similar packaging and flavors across the range of FMB and spirits products was designed to allow the promotion of the brand on broadcast television and to recast Smirnoff as a youth-oriented brand. Other cross-branded products including Skyy and Bacardi followed similar strategies. The study also documents increased drinking and spirits preference among young women during this period. Our results suggest that this same cohort has continued to drink more heavily and to drink more spirits relative to earlier cohorts into their late 20’s.

The third potential factor influencing recent cohort’s drinking patterns has been the trend in slowly rising per capita alcohol sales coinciding with the promotion of the alleged health benefits of alcohol since the early 1990’s. [25] This period has also seen an expanding wine, craft beer and cocktail culture and significant quality upgrading for beer, wine and spirits through 2007, with some reversal in 2008 and 2009 due to the recession. [23] This attention to quality and preparation suggests greater alcohol involvement and may have worked in tandem with alcohol affordability and spirits promotion to generate the estimated cohort effects.

Limitations

There are limitations to the comparison of estimates across general population surveys. Due to a lack of information about earlier surveys, alcohol volume and heavy drinking measures are not adjusted for drink alcohol content, which is known to vary across beverage types, contexts and individual characteristics [26] and may also vary over time. Under-reporting of alcohol consumption is an issue in any survey and differential effects across age, survey and cohort cannot be determined. [27] Most importantly, estimated APC models assume independent effects of age, period and cohort and do not allow for potential interactions between these aspects that may have occurred. Our results should be confirmed in alternative US survey series and other data allowing APC analyses such as longitudinal panels and alcohol-related mortality rates.

Conclusion

Whatever the reasons for heavier drinking in the 1976–85 birth cohorts who began their drinking careers during the 1990s and early 2000s, the identification of a cohort effect for this group implies a high likelihood of continued relatively heavy drinking into the future. Risk curve analyses and theory [28] suggests that the behavior of this birth cohort will be accompanied by increased levels of alcohol dependence and alcohol-related health and social consequences compared to other cohorts, even as many mature out of heavy drinking to some degree. Efforts to influence drinkers in these birth cohorts to reduce drinking and minimize harm through brief interventions, expanded access to treatment and strengthened alcohol policies effecting price and availability are needed. Attention is warranted to policies involving price and availability of alcohol during the late adolescent period where what may become long-term drinking patterns are developed. Beverage-specific results are also relevant to alcohol-related problem prevention indicating that while beer has accounted for much of the excess drinking among young people, drinking spirits has become relatively more popular among today’s youth. This shift to spirits is a concern because spirits have been found to be more strongly associated than other beverage types with alcohol-related mortality causes such as cirrhosis in the US during the 20th century. [29]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism National Alcohol Research Center Grant P50-AA005595 to the Alcohol Research Group, public Health Institute.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: None

Contributor Information

William C. Kerr, Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute, Emeryville CA, USA

Thomas K. Greenfield, Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute, Emeryville CA, USA

Yu Ye, Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute, Emeryville CA, USA.

Jason Bond, Alcohol Research Group, Public Health Institute, Emeryville CA, USA.

Jürgen Rehm, Epidemiological Research Unit, Technische Universität Dresden, Klinische Psychologie and Psychotherapie, Dresden, Germany; Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Canada; Public Health and Regulatory Policies, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.LaVallee RA, Yi H-y. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health; 2010. Aug, [Accessed: 2011-09-1 3]. Apparent per capita alcohol alcohol consumption: national, state, and regional trends, 1977–2008. (Surveillance Report #90) Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/61fqKpdoo. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age, period and cohort influences on beer, wine and spirits consumption trends in the US National Surveys. Addiction. 2004 Sep;99(9):1111–1120. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age-period-cohort influences on trends in past year marijuana use in the U.S. from the 1984, 1990, 1995, and 2000 National Alcohol Surveys. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 Jan;86(2–3):132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J. Age-period-cohort modeling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction. 2009 Jan;104(1):27–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grucza RA, Bucholz KK, Rice JP, Bierut LJ. Secular trends in the lifetime prevalence of alcohol dependence in the United States: a re-evaluation. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008 May;32(5):763–770. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. Effects of telephone versus face-to-face interview modes on reports of alcohol consumption. Addiction. 2000 Feb;95(2):227–284. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95227714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Midanik LT, Rogers JD, Greenfield TK. Mode differences in reports of alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm. In: Cynamon ML, Kulka RA, editors. Seventh Conference on Health Survey Research Methods. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. pp. 129–133. [DHHS Publication No (PHS) 01-1013] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tourangeau R. Survey research and societal change. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:775–801. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gmel G, Rehm J. Measuring alcohol consumption. Contemp Drug Prob. 2004 Fall;31(3):467–540. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerr WC. Categorizing US state drinking practices and consumption trends. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2010 Jan;7(1):269–283. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7010269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenfield TK, Midanik LT, Rogers JD. A Ten-year National Trend Study of Alcohol Consumption 1984–1995: is the period of declining drinking over? Am J Public Health. 2000 Jan;90(1):47–52. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stata Corp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 10.0. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y. Aging, cohorts, and methods. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences. 7th ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2011. pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golub GH, Van Loan CF. Matrix Computations. 3rd. ed. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. Price List No. 45. Harrisburg, PA: 1950. Apr 1, [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. State Store Price List No. 74. Harrisburg, PA: 1960. Apr 1, [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. The Pennsylvania Liquor Control Boards Product Price List. Harrisburg, PA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. Pennsylvania's Official Wine and Liquor Quarterly. Harrisburg, PA: 1995. Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board. Pennsylvania's Official Wine and Liquor Quarterly. Harrisburg, PA: 2000. Spring. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman DG. Alternative panel estimates of alcohol demand, taxation, and the business cycle. So Econ J. 2000 Oct;67(2):325–344. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruhm CJ, Black WE. Does drinking really decrease in bad times? J Health Econ. 2002 Jul;21(4):659–678. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(02)00033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams Beverage Group. Adams Liquor Handbook. Norwalk, CT: Adams, CT: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Beverage Information Group. Liquor Handbook. Norwalk, CT: The Beverage Handbook; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mosher JF. Joe Camel in a bottle: Diageo, the Smirnoff brand, and the transformation of the youth alcohol market. Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300387. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renaud S, deLorgeril M. Wine, alcohol, platelets, and the French paradox for coronary heart disease. The Lancet. 1992 Jun 20;339(8808):1523–1526. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91277-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerr WC, Patterson D, Greenfield TK. Differences in the measured alcohol content of drinks between black, white and Hispanic men and women in a US national sample. Addiction. 2009;104(9):1503–1511. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerr WC, Greenfield TK. Distribution of alcohol consumption and expenditures and the impact of improved measurement on coverage of alcohol sales in the 2000 National Alcohol Survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007 Oct;31(10):1714–1722. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rehm J, Baliunas D, Borges GLG, Graham K, Irving H, Kehoe T, et al. The relationship between different dimensions of alcohol consumption and burden of disease: an overview. Addiction. 2010 May;105(5):817–843. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kerr WC, Ye Y. Beverage-specific mortality relationships in US population data. Contemp Drug Prob. 2011 Winter;38:561–578. doi: 10.1177/009145091103800406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]