Abstract

Chronic heart failure (CHF) impairs nitric oxide (NO)-mediated regulation of the skeletal muscle microvascular O2 delivery/ ratio (which sets the microvascular O2 pressure,

ratio (which sets the microvascular O2 pressure,  ). Given the pervasiveness of endothelial dysfunction in CHF, this NO-mediated dysregulation is attributed generally to eNOS. It is unknown whether nNOS-mediated

). Given the pervasiveness of endothelial dysfunction in CHF, this NO-mediated dysregulation is attributed generally to eNOS. It is unknown whether nNOS-mediated  regulation is altered in CHF. We tested the hypothesis that CHF impairs nNOS-mediated

regulation is altered in CHF. We tested the hypothesis that CHF impairs nNOS-mediated  control. In healthy and CHF (left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP): 6 ± 1 versus 14 ± 1 mmHg, respectively, P < 0.05) rats spinotrapezius muscle blood flow (radiolabelled microspheres),

control. In healthy and CHF (left ventricular end diastolic pressure (LVEDP): 6 ± 1 versus 14 ± 1 mmHg, respectively, P < 0.05) rats spinotrapezius muscle blood flow (radiolabelled microspheres),  (phosphorescence quenching), and

(phosphorescence quenching), and  (Fick calculation) were measured before and after 0.56 mg kg−1

i.a. of the selective nNOS inhibitor S-methyl-l-thiocitrulline (SMTC). In healthy rats, SMTC increased baseline

(Fick calculation) were measured before and after 0.56 mg kg−1

i.a. of the selective nNOS inhibitor S-methyl-l-thiocitrulline (SMTC). In healthy rats, SMTC increased baseline  (Control: 29.7 ± 1.4, SMTC: 34.4 ± 1.9 mmHg, P < 0.05) by reducing

(Control: 29.7 ± 1.4, SMTC: 34.4 ± 1.9 mmHg, P < 0.05) by reducing  (↓20%) without any effect on blood flow and speeded the mean response time (MRT, time to reach 63% of the overall kinetics response, Control: 24.2 ± 2.0, SMTC: 18.5 ± 1.3 s, P < 0.05). In CHF rats, SMTC did not alter baseline

(↓20%) without any effect on blood flow and speeded the mean response time (MRT, time to reach 63% of the overall kinetics response, Control: 24.2 ± 2.0, SMTC: 18.5 ± 1.3 s, P < 0.05). In CHF rats, SMTC did not alter baseline  (Control: 25.7 ± 1.6, SMTC: 28.6 ± 2.1 mmHg, P > 0.05),

(Control: 25.7 ± 1.6, SMTC: 28.6 ± 2.1 mmHg, P > 0.05),  at rest, or the MRT (Control: 22.8 ± 2.6, SMTC: 21.3 ± 3.0 s, P > 0.05). During the contracting steady-state, SMTC reduced blood flow (↓15%) and

at rest, or the MRT (Control: 22.8 ± 2.6, SMTC: 21.3 ± 3.0 s, P > 0.05). During the contracting steady-state, SMTC reduced blood flow (↓15%) and  (↓15%) in healthy rats such that

(↓15%) in healthy rats such that  was unaltered (Control: 19.8 ± 1.7, SMTC: 20.7 ± 1.8 mmHg, P > 0.05). In marked contrast, in CHF rats SMTC did not change contracting steady-state blood flow,

was unaltered (Control: 19.8 ± 1.7, SMTC: 20.7 ± 1.8 mmHg, P > 0.05). In marked contrast, in CHF rats SMTC did not change contracting steady-state blood flow,  , or

, or  (Control: 17.0 ± 1.4, SMTC: 17.7 ± 1.8 mmHg, P > 0.05). nNOS-mediated control of skeletal muscle microvascular function is compromised in CHF versus healthy rats. Treatments designed to ameliorate microvascular dysfunction in CHF may benefit by targeting improvements in nNOS function.

(Control: 17.0 ± 1.4, SMTC: 17.7 ± 1.8 mmHg, P > 0.05). nNOS-mediated control of skeletal muscle microvascular function is compromised in CHF versus healthy rats. Treatments designed to ameliorate microvascular dysfunction in CHF may benefit by targeting improvements in nNOS function.

Key points

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important vasodilatory signalling molecule that regulates O2 pressure within the skeletal muscle microvasculature (

). In healthy subjects, NO is derived from two principal NO synthase (NOS) isoforms: neuronal NOS (nNOS) and endothelial NOS (eNOS).

). In healthy subjects, NO is derived from two principal NO synthase (NOS) isoforms: neuronal NOS (nNOS) and endothelial NOS (eNOS).Chronic heart failure (CHF) results in peripheral vascular dysfunction that is attributed, in part, to impaired NO function. This NO-mediated impairment is attributed generally to eNOS dysfunction. It is unknown if nNOS-mediated regulation of

function is impaired in CHF.

function is impaired in CHF.Our present results demonstrate that skeletal muscle blood flow reductions and

alterations during contractions observed following nNOS inhibition in healthy rats are markedly attenuated or absent in CHF rats, which is indicative of impaired nNOS function.

alterations during contractions observed following nNOS inhibition in healthy rats are markedly attenuated or absent in CHF rats, which is indicative of impaired nNOS function.Identification of the mechanisms underlying impaired microvascular function in CHF is an important step in the development of treatments designed to improve CHF-induced skeletal muscle microvascular pathology.

Introduction

The ability of the skeletal muscle microvasculature to modulate O2 delivery relative to O2 demand both spatially and temporally during contractions is a fundamental feature of integrated cardiorespiratory function. In healthy subjects, the skeletal muscle microvascular O2 delivery/ balance (which sets the

balance (which sets the  and represents the pressure head driving blood-myocyte O2 flux according to Fick's law of diffusion) at rest and during contractions is dependent critically upon adequate NO bioavailability (Ferreira et al. 2006b; Hirai et al. 2010) derived via constitutively expressed neuronal (Type I) and endothelial (Type III) NOS isoforms. The contribution of inducible NOS (iNOS, Type II) in young healthy individuals is expected to be minimal.

and represents the pressure head driving blood-myocyte O2 flux according to Fick's law of diffusion) at rest and during contractions is dependent critically upon adequate NO bioavailability (Ferreira et al. 2006b; Hirai et al. 2010) derived via constitutively expressed neuronal (Type I) and endothelial (Type III) NOS isoforms. The contribution of inducible NOS (iNOS, Type II) in young healthy individuals is expected to be minimal.

CHF is a clinical syndrome marked by perturbations in peripheral vascular (Longhurst et al. 1976) and metabolic (Massie et al. 1987) regulation which contribute to compromised  control (Diederich et al. 2002; Copp et al. 2010a) and exercise intolerance (Nicoletti et al. 2003; Poole et al. 2012). Impairments in NO-mediated function explain, at least in part, CHF-induced reductions in bulk contracting muscle O2 delivery (Katz et al. 1996) as well as derangements in peripheral skeletal muscle spatial (Hirai et al. 1995) and temporal (Ferreira et al. 2006a) O2 delivery relative to O2 demand. For example, non-selective NOS inhibition with l-NAME lowers contracting skeletal muscle

control (Diederich et al. 2002; Copp et al. 2010a) and exercise intolerance (Nicoletti et al. 2003; Poole et al. 2012). Impairments in NO-mediated function explain, at least in part, CHF-induced reductions in bulk contracting muscle O2 delivery (Katz et al. 1996) as well as derangements in peripheral skeletal muscle spatial (Hirai et al. 1995) and temporal (Ferreira et al. 2006a) O2 delivery relative to O2 demand. For example, non-selective NOS inhibition with l-NAME lowers contracting skeletal muscle  to a greater extent in healthy versus CHF rats revealing reduced NO bioavailability and impaired NO-mediated microvascular function in CHF (Ferreira et al. 2006a). Given the pervasive reports of compromised endothelial function in CHF subjects (Kaiser et al. 1989; Katz et al. 1992), the tacit presumption has been that those reductions in NO bioavailability reflect principally eNOS dysfunction. Recently, however, selective nNOS inhibition with S-methyl-l-thiocitrulline (SMTC) (Furfine et al. 1994; Wakefield et al. 2003) reduced healthy rat skeletal muscle blood flow and

to a greater extent in healthy versus CHF rats revealing reduced NO bioavailability and impaired NO-mediated microvascular function in CHF (Ferreira et al. 2006a). Given the pervasive reports of compromised endothelial function in CHF subjects (Kaiser et al. 1989; Katz et al. 1992), the tacit presumption has been that those reductions in NO bioavailability reflect principally eNOS dysfunction. Recently, however, selective nNOS inhibition with S-methyl-l-thiocitrulline (SMTC) (Furfine et al. 1994; Wakefield et al. 2003) reduced healthy rat skeletal muscle blood flow and  revealing a novel role for nNOS-derived NO specifically in the regulation of

revealing a novel role for nNOS-derived NO specifically in the regulation of  at rest and during contractions (Copp et al. 2011). Whether this nNOS-derived NO regulation of

at rest and during contractions (Copp et al. 2011). Whether this nNOS-derived NO regulation of  is altered in CHF is unknown. However, Thomas et al. (2001) reported that the attenuation of sympathetic vasoconstrictor activity in contracting hindlimb muscles is impaired (i.e. less sympathetic vasoconstrictor amelioration is present) in CHF versus healthy rats. Considering that this ‘functional sympatholysis’ emanates predominately from nNOS-derived NO (Thomas et al. 2001), indirect evidence supports that nNOS function is reduced in CHF and may therefore contribute to the impaired NO-mediated microvascular function, although this conclusion has not been tested specifically. Clouding this issue are inconsistent reports that nNOS protein expression may be increased (Rush et al. 2005) or unchanged (Thomas et al. 2001; Rush et al. 2005) in CHF rats and humans compared to healthy counterparts. Moreover, the possibility of CHF-induced NOS uncoupling (reviewed by Munzel et al. 2005) signifies that altered nNOS protein levels in CHF may not necessarily match changes (or the lack thereof) in nNOS expression. Therefore, direct assessment of the presence and extent of compromised nNOS-mediated

is altered in CHF is unknown. However, Thomas et al. (2001) reported that the attenuation of sympathetic vasoconstrictor activity in contracting hindlimb muscles is impaired (i.e. less sympathetic vasoconstrictor amelioration is present) in CHF versus healthy rats. Considering that this ‘functional sympatholysis’ emanates predominately from nNOS-derived NO (Thomas et al. 2001), indirect evidence supports that nNOS function is reduced in CHF and may therefore contribute to the impaired NO-mediated microvascular function, although this conclusion has not been tested specifically. Clouding this issue are inconsistent reports that nNOS protein expression may be increased (Rush et al. 2005) or unchanged (Thomas et al. 2001; Rush et al. 2005) in CHF rats and humans compared to healthy counterparts. Moreover, the possibility of CHF-induced NOS uncoupling (reviewed by Munzel et al. 2005) signifies that altered nNOS protein levels in CHF may not necessarily match changes (or the lack thereof) in nNOS expression. Therefore, direct assessment of the presence and extent of compromised nNOS-mediated  regulation in CHF is warranted. This information is critical considering that elucidation of the mechanisms responsible for impaired O2 transport and

regulation in CHF is warranted. This information is critical considering that elucidation of the mechanisms responsible for impaired O2 transport and  in CHF may lead to new therapeutic treatment modalities.

in CHF may lead to new therapeutic treatment modalities.

The purpose of the present investigation is to determine if the nNOS-derived NO control of skeletal muscle blood flow,  , and the dynamic blood flow/

, and the dynamic blood flow/ ratio (i.e.

ratio (i.e.  ) during contractions is compromised in CHF versus healthy rats. We tested the hypothesis that CHF rats would demonstrate blunted or absent

) during contractions is compromised in CHF versus healthy rats. We tested the hypothesis that CHF rats would demonstrate blunted or absent  alterations following nNOS inhibition with SMTC when compared to healthy rats.

alterations following nNOS inhibition with SMTC when compared to healthy rats.

Methods

Ethical approval

All experimental protocols described herein were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Kansas State University and conducted in agreement with the guidelines established by the National Institutes of Health and The Journal of Physiology (Drummond, 2009). Novel experiments in healthy rats (n = 6, 4  /blood flow and 2 force production/ACh) were added to previously reported data from healthy animals (n = 15, Copp et al. 2011) to give the present healthy rat data. This strategy was required to cohere with the IACUC mandate to avoid unnecessary animal killing.

/blood flow and 2 force production/ACh) were added to previously reported data from healthy animals (n = 15, Copp et al. 2011) to give the present healthy rat data. This strategy was required to cohere with the IACUC mandate to avoid unnecessary animal killing.

Animals

A total of 40 male Sprague–Dawley rats (∼6 months old, Charles River Laboratories, Boston, MA, USA) were used in the present investigation. All rats were housed in accredited facilities and maintained on a 12:12 h light–dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum for the duration of the experimental protocol.

Surgical procedures

Myocardial infarction was induced in CHF rats via left main coronary artery ligation (Musch & Terrell, 1992). To begin, CHF rats were anaesthetized with a 5% isoflurane (Butler Animal Health Supply, Elk Grove Village, IL, USA)–95% O2 (Linweld, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) mixture and intubated for mechanical ventilation with a rodent respirator (Harvard Model 680; Harvard Instruments, Holliston, MA, USA) for the duration of the surgical procedure. The heart was accessed through a left thoracotomy in the fifth intercostal space. The left main coronary artery was ligated with 6–0 silk suture approximately 1–2 mm distal to the edge of the left atrium. The incision was then closed, and ampicillin (50 mg kg−1 i.m.) was injected locally to reduce opportunity for infection. The analgesic agents bupivacaine (1.5 mg kg−1 subcutaneously) and buprenorphine (0.01–0.05 mg kg−1 i.m.) were administered subsequently and anaesthesia and mechanical ventilation discontinued. All rats were monitored closely for ≥6 h for arrhythmia development and signs of undue distress (i.e. laboured breathing, etc.) with care administered as appropriate. Rats were also monitored daily (i.e. appetite, weight loss/gain, gait/posture, etc.) according to an intensive 10 day post-operative plan conducted in conjunction with the university veterinary staff.

The final experimental protocol was initiated ≥21 days after surgery. Healthy rats were not subjected to a sham surgical procedure given there are no differences in cardiovascular responses between sham operated and non-sham operated healthy animals (Symons et al. 1999). Rats were anaesthetized initially with a 5% isoflurane–O2 mixture and maintained at 2–3% isoflurane. The carotid artery was cannulated and a two-French-catheter-tipped pressure transducer (Millar Instruments, Houston, TX, USA) was advanced into the LV for measurement of systolic and diastolic pressures and left ventricular delta pressure/delta time (LV dp/dt). Upon completion of the measurement, the transducer was removed and the carotid artery was re-cannulated with a catheter (PE-10 connected to PE-50, Intra-Medic polyethylene tubing, Clay Adams Brand, Benton, Dickson and Company, Sparks, MD, USA) for measurement of MAP, infusion of the phosphorescent probe, and arterial blood sampling. A catheter (PE-50) was also placed in the caudal (tail) artery. Rats were then transitioned progressively to pentobarbital sodium (administered i.a. to effect), monitored continuously via the toe-pinch and blink reflexes with anaesthesia supplemented as necessary, and placed on a heating pad to maintain core temperature at 38°C (measured via rectal probe). Overlying skin and fascia were then reflected carefully from the mid-dorsal–caudal region of each rat and the right spinotrapezius muscle was exposed in a manner which ensured the integrity of the vascular and neural supply to the muscle (Bailey et al. 2000). Silver wire electrodes were then sutured (6–0 silk) to the rostral (cathode) and caudal (anode) regions of the muscle. The exposed spinotrapezius muscle was continuously superfused with a warmed (38°C) Krebs–Henseleit bicarbonate buffered solution equilibrated with 5% CO2–95% N2 and surrounding exposed tissue was covered with Saran wrap (Dow Brands, Indianapolis, IN, USA).

Experimental protocol

In 14 (461 ± 25 g) healthy and 12 (528 ± 17 g, P < 0.05) CHF rats, the phosphorescent probe palladium meso-tetra(4-carboxyphenyl)porphyrin dendrimer (R2, Oxygen Enterprises, Philadelphia, PA, USA: 15–20 mg kg−1 dissolved in saline) was infused via the carotid artery catheter. After a ∼15 min stabilization period, the carotid artery catheter was connected to a pressure transducer for continuous monitoring of HR and MAP and  measurements (see below) were initiated. Subsequently, 1.2 ml of heparinized saline was infused at a rate of 0.2 ml min−1 into the caudal artery catheter to serve as a time and volume control infusion. Following the infusion the caudal artery catheter was connected to a 1 ml plastic syringe and placed in a withdrawl pump (model 907, Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, MA, USA). Twitch contractions of 1 Hz (∼6–8 V, 2 ms pulse duration) were then initiated via a stimulator (model S88, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA). At 180 s of contractions blood withdrawal from the tail catheter was initiated at a rate of 0.25 ml min−1, the carotid catheter was disconnected from the pressure transducer, and ∼0.5–0.6 × 106 radiolabelled microspheres (15 μm in diameter, 46Sc or 85Sr in random order, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) were infused rapidly into the aortic arch for determination of blood flow in accordance with the reference sample method (Ishise et al. 1980, see below for details), and contractions were then terminated. Following a minimum 20 min recovery period, 0.56 mg kg−1 (2.1 μmol kg−1) of SMTC was dissolved in 1.2 ml of heparinized saline and infused as described above. Following the infusion and once it was observed that

measurements (see below) were initiated. Subsequently, 1.2 ml of heparinized saline was infused at a rate of 0.2 ml min−1 into the caudal artery catheter to serve as a time and volume control infusion. Following the infusion the caudal artery catheter was connected to a 1 ml plastic syringe and placed in a withdrawl pump (model 907, Harvard Apparatus, Cambridge, MA, USA). Twitch contractions of 1 Hz (∼6–8 V, 2 ms pulse duration) were then initiated via a stimulator (model S88, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA). At 180 s of contractions blood withdrawal from the tail catheter was initiated at a rate of 0.25 ml min−1, the carotid catheter was disconnected from the pressure transducer, and ∼0.5–0.6 × 106 radiolabelled microspheres (15 μm in diameter, 46Sc or 85Sr in random order, Perkin Elmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA, USA) were infused rapidly into the aortic arch for determination of blood flow in accordance with the reference sample method (Ishise et al. 1980, see below for details), and contractions were then terminated. Following a minimum 20 min recovery period, 0.56 mg kg−1 (2.1 μmol kg−1) of SMTC was dissolved in 1.2 ml of heparinized saline and infused as described above. Following the infusion and once it was observed that  was stable for at least 30 s, contraction and microsphere injection protocols were performed as described for control. Blood samples were taken after each contraction protocol to determine arterial [O2] and blood [lactate]. Following the experimental protocol rats were killed via an intra-arterial pentobarbital overdose (∼50 mg kg−1). For each rat, the lungs and heart were carefully removed and dissected. The lungs and right ventricle (RV) were weighed and normalized to body mass. For CHF rats, infarct size was determined via planimetry as described previously (Ferreira et al. 2006a).

was stable for at least 30 s, contraction and microsphere injection protocols were performed as described for control. Blood samples were taken after each contraction protocol to determine arterial [O2] and blood [lactate]. Following the experimental protocol rats were killed via an intra-arterial pentobarbital overdose (∼50 mg kg−1). For each rat, the lungs and heart were carefully removed and dissected. The lungs and right ventricle (RV) were weighed and normalized to body mass. For CHF rats, infarct size was determined via planimetry as described previously (Ferreira et al. 2006a).

Measurement of  and curve-fitting

and curve-fitting

The Stern–Volmer relationship allows the calculation of  through the direct measurement of a phosphorescence lifetime via the following equation (Rumsey et al. 1988):

through the direct measurement of a phosphorescence lifetime via the following equation (Rumsey et al. 1988):

where kQ is the quenching constant (expressed in mmHg−1 s−1) and τ° and τ are the phosphorescence lifetimes in the absence of O2 and the ambient O2 concentration, respectively. For R2, kQ is 409 mmHg−1 s−1 and τ° is 601 μs (Lo et al. 1997) and these characteristics do not change appreciably over the physiological range of pH and temperature in the rat in vivo herein and, therefore, the phosphorescence lifetime is determined directly by the O2 pressure (Rumsey et al. 1988; Lo et al. 1997).

The R2 phosphorescent probe binds to albumin, and consequently is uniformly distributed throughout the plasma. A previous study from our laboratory investigated systematically the compartmentalization of R2 and confirmed that it remains within the microvasculature of exposed muscle over the duration considered in the present experiments, thereby ensuring a valid measurement of  (Poole et al. 2004). The

(Poole et al. 2004). The  was determined with a PMOD 5000 Frequency Domain Phosphorometer (Oxygen Enterprises, Philadelphia, PA, USA). The common end of the light guide was placed ∼2–4 mm superficial to the dorsal surface of the exposed right spinotrapezius muscle. The randomly selected muscle field was composed principally of capillary blood and

was determined with a PMOD 5000 Frequency Domain Phosphorometer (Oxygen Enterprises, Philadelphia, PA, USA). The common end of the light guide was placed ∼2–4 mm superficial to the dorsal surface of the exposed right spinotrapezius muscle. The randomly selected muscle field was composed principally of capillary blood and  was measured continuously and recorded at 2 s intervals throughout the duration of the contraction periods.

was measured continuously and recorded at 2 s intervals throughout the duration of the contraction periods.

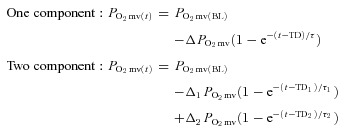

For the measured  responses, curve-fitting was performed with commercially available software (SigmaPlot 11.2, Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) and the data were fit with either a one- or two-component model as described below:

responses, curve-fitting was performed with commercially available software (SigmaPlot 11.2, Systat Software, San Jose, CA, USA) and the data were fit with either a one- or two-component model as described below:

|

where  represents the

represents the  at any given time t,

at any given time t,  corresponds to the pre-contracting resting

corresponds to the pre-contracting resting  , Δ1 and Δ2 are the amplitudes for the first and second component, respectively, TD1 and TD2 are the time delays for each component, and τ1 and τ2 are the time constants (i.e. time to 63% of the final response value) for each component. Goodness of fit was determined using the following criteria: (1) the coefficient of determination, (2) sum of the squared residuals, and (3) visual inspection and analysis of the model fits to the data and the residuals. The MRT of the kinetics response was calculated for the first component in order to provide an index of the overall principal kinetics response according to the following equation:

, Δ1 and Δ2 are the amplitudes for the first and second component, respectively, TD1 and TD2 are the time delays for each component, and τ1 and τ2 are the time constants (i.e. time to 63% of the final response value) for each component. Goodness of fit was determined using the following criteria: (1) the coefficient of determination, (2) sum of the squared residuals, and (3) visual inspection and analysis of the model fits to the data and the residuals. The MRT of the kinetics response was calculated for the first component in order to provide an index of the overall principal kinetics response according to the following equation:

where TD1 and τ1 are as described above. The delta of the initial  fall following contractions onset was normalized to τ1 (

fall following contractions onset was normalized to τ1 ( ) to provide an index of the relative rate of fall.

) to provide an index of the relative rate of fall.

Determination of muscle blood flow and calculation of

Following killing, the right and left spinotrapezius muscles and kidneys were carefully dissected, removed from each rat and weighed. The radioactivity of the spinotrapezius muscles and reference blood samples taken from the tail artery catheter during microsphere infusions were determined via a gamma scintillation counter (Auto Gamma Spectrometer, Cobra model 5003, Hewlett-Packard, Downers Grove, IL, USA) and individual tissue blood flows were expressed in ml min−1 (100 g tissue)−1 (Ishise et al. 1980). In each condition (control and SMTC) the stimulated right, and non-stimulated left, spinotrapezius muscles represented the contracting and resting blood flow measurements, respectively. Vascular conductance (VC) was determined as the ratio of blood flow to MAP using the MAP measured immediately prior to each microsphere injection. All rats exhibited <15% difference in blood flow between the right and left kidneys which indicated an adequate mixing of microspheres during the blood flow determinations. was calculated from blood flow and

was calculated from blood flow and  measurements. Arterial O2 concentration (

measurements. Arterial O2 concentration ( ) was calculated directly from arterial blood samples and venous muscle effluent blood O2 concentration (

) was calculated directly from arterial blood samples and venous muscle effluent blood O2 concentration ( ) was approximated from either the baseline (rest) or the contracting steady-state

) was approximated from either the baseline (rest) or the contracting steady-state  using the rat dissociation curve (Hill's coefficient of 2.6), the measured haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]), a P50 of 38 mmHg, and an O2 carrying capacity of 1.34 ml O2 (g Hb)−1 (Altman & Dittmer, 1974). The measures of the resting and contracting spinotrapezius blood flows were then used to determine

using the rat dissociation curve (Hill's coefficient of 2.6), the measured haemoglobin concentration ([Hb]), a P50 of 38 mmHg, and an O2 carrying capacity of 1.34 ml O2 (g Hb)−1 (Altman & Dittmer, 1974). The measures of the resting and contracting spinotrapezius blood flows were then used to determine  via the direct Fick calculation (i.e.

via the direct Fick calculation (i.e.  ).

).

Measurement of muscle force production

Due to differences in surgical preparation required for muscle force and  measurement, additional groups of rats (healthy: n = 7, 469 ± 10 g; CHF: n = 7, 475 ± 26 g, P > 0.05) were utilized to determine the effects of CHF on nNOS-mediated control of skeletal muscle force production. In these animals, the caudal end of the exposed spinotrapezius muscle was exteriorized and sutured to a thin, wire horseshoe manifold attached to a swivel apparatus and a non-distensible light-weight (0.4 g) cable which linked the muscle to a force transducer (model FTO3, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA). Rats were placed on a custom-made stabilization platform and the pre-load muscle tension was set to ∼4 g which elicited the muscle's optimum length for twitch force production. Muscle force production was measured throughout control and SMTC contraction bouts as described for the measurement of

measurement, additional groups of rats (healthy: n = 7, 469 ± 10 g; CHF: n = 7, 475 ± 26 g, P > 0.05) were utilized to determine the effects of CHF on nNOS-mediated control of skeletal muscle force production. In these animals, the caudal end of the exposed spinotrapezius muscle was exteriorized and sutured to a thin, wire horseshoe manifold attached to a swivel apparatus and a non-distensible light-weight (0.4 g) cable which linked the muscle to a force transducer (model FTO3, Grass Instrument Co., Quincy, MA, USA). Rats were placed on a custom-made stabilization platform and the pre-load muscle tension was set to ∼4 g which elicited the muscle's optimum length for twitch force production. Muscle force production was measured throughout control and SMTC contraction bouts as described for the measurement of  . Rats were then killed as described above. A previous report from our laboratory indicates that

. Rats were then killed as described above. A previous report from our laboratory indicates that  and blood flow do not differ between exposed and exteriorized spinotrapezius muscle (Bailey et al. 2000).

and blood flow do not differ between exposed and exteriorized spinotrapezius muscle (Bailey et al. 2000).

Acetylcholine infusions

In order to examine the efficacy of selective nNOS inhibition in the presence of SMTC, rapid ACh infusions (10 μg kg−1 in 0.2 ml of saline) were performed in subsets of CHF (n = 6) and healthy rats (n = 7) under control and SMTC conditions as well as following non-selective NOS inhibition with 10 mg kg−1 of l-NAME administered into the caudal artery. ACh was infused rapidly into the caudal artery catheter while MAP was simultaneously recorded via the carotid artery catheter. The time to 50% of the recovery from the hypotensive MAP response to ACh was measured and recorded. Analysis of haemodynamic responses to ACh infusion has been employed previously to examine the efficacy of selective nNOS inhibition with SMTC in both animals (Wakefield et al. 2003; Copp et al. 2010b, 2011) and humans (Seddon et al. 2008, 2009).

Statistical analyses

Data for primary study endpoints were compared within (control vs. SMTC) and among (healthy vs. CHF) groups by mixed ANOVAs with the Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test when significant interactions were indicated. Other comparisons were performed via paired or unpaired Student's t tests where appropriate. The z test was performed to test when variable changes following SMTC were different from zero. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

Efficacy of CHF induction

The haemodynamic and morphological indices of CHF are presented in Table 1 and indicate that CHF rats had moderate compensated CHF (Diederich et al. 2002).

Table 1.

Morphological and haemodynamic characteristics of healthy and CHF rats

| Healthy | CHF | |

|---|---|---|

| LVEDP (mmHg) | 6 ± 1 | 14 ± 1* |

| RV/body mass (mg g−1) | 0.61 ± 0.03 | 0.68 ± 0.03* |

| Lung/body mass (mg g−1) | 3.56 ± 0.14 | 4.38 ± 0.30 |

| LV dp/dt (mmHg s−1) | 8109 ± 168 | 7113 ± 163* |

| Infarct size (%) | — | 27.9 ± 1.6% |

LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure; RV, right ventricle; LV dp/dt, left ventricular dpressure/dtime.

P < 0.05 versus healthy rats.

Effects of CHF on nNOS-mediated blood [lactate] and central haemodynamic regulation

SMTC did not change blood [lactate] in healthy (control: 1.0 ± 0.1, SMTC: 1.0 ± 0.1 mmol l−1, P > 0.05) or CHF rats (control: 1.0 ± 0.2, SMTC: 1.1 ± 0.1 mmol l−1, P > 0.05). In healthy and CHF rats SMTC elevated MAP and reduced HR compared to control at rest and during contractions steady-state (Table 2). The SMTC-induced MAP elevations (ΔMAP) were significantly attenuated in CHF versus healthy rats at rest and during contractions (P < 0.05 for both).

Table 2.

Effects of selective nNOS inhibition with SMTC on HR and MAP in healthy and CHF rats

| Healthy | CHF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | SMTC | Δ | Control | SMTC | Δ | |

| Rest | ||||||

| HR (bpm) | 351 ± 9 | 319 ± 8* | −32 ± 8 | 371 ± 8 | 353 ± 8*† | −18 ± 9 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 111 ± 4 | 131 ± 5* | 19 ± 3 | 124 ± 4† | 134 ± 5* | 11 ± 3† |

| Contractions (steady-state) | ||||||

| HR (bpm) | 352 ± 9 | 323 ± 9* | −30 ± 7 | 372 ± 9 | 354 ± 7*† | −18 ± 9 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 115 ± 4 | 133 ± 5* | 18 ± 2 | 124 ± 4 | 132 ± 6* | 10 ± 2† |

Values are means ± SEM, *P < 0.05 versus control, †P < 0.05 versus healthy.

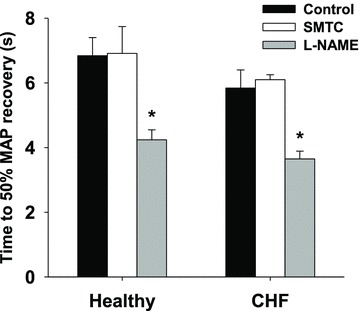

In healthy and CHF rats the time to 50% recovery from the hypotensive response to rapid ACh infusions was not different between control and SMTC conditions whereas it was reduced following l-NAME (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Effects of SMTC and l-NAME on the 50% recovery time from the hypotensive effects of rapid ACH infusions.

Data are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control and SMTC for healthy (n = 7) and CHF (n = 6) rats.

Effects CHF on nNOS-mediated  , blood flow and

, blood flow and  regulation

regulation

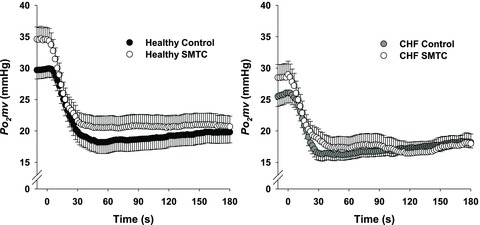

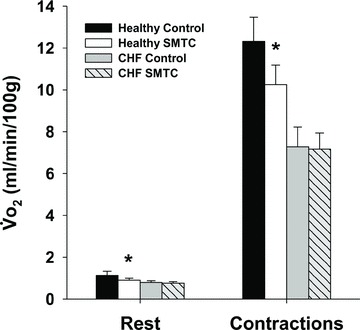

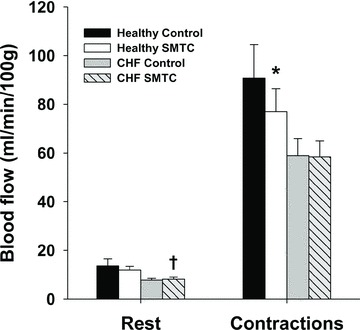

In healthy rats, SMTC increased baseline  (Fig. 2, Table 3) consequent to a 20% reduction in resting

(Fig. 2, Table 3) consequent to a 20% reduction in resting  (Fig. 3) with no effect on resting blood flow (Fig. 4). In CHF rats, SMTC did not alter resting baseline

(Fig. 3) with no effect on resting blood flow (Fig. 4). In CHF rats, SMTC did not alter resting baseline  , blood flow, or

, blood flow, or  (P > 0.05 for all). Following onset of contractions, SMTC resulted in a shorter TD1 and faster MRT and

(P > 0.05 for all). Following onset of contractions, SMTC resulted in a shorter TD1 and faster MRT and  in healthy rats whereas only a shorter TD1 following SMTC was found in CHF rats. During the contracting steady-state, SMTC reduced blood flow (↓15%) and

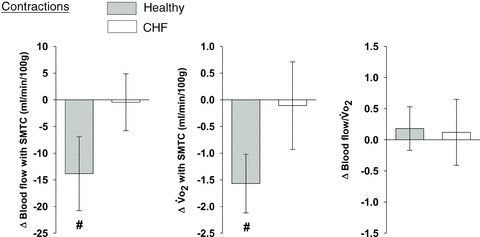

in healthy rats whereas only a shorter TD1 following SMTC was found in CHF rats. During the contracting steady-state, SMTC reduced blood flow (↓15%) and  (↓15%) in healthy rats such that

(↓15%) in healthy rats such that  and Δ blood flow/

and Δ blood flow/ ratio were unaltered (Fig. 5). SMTC did not change contracting steady-state blood flow,

ratio were unaltered (Fig. 5). SMTC did not change contracting steady-state blood flow,  , Δ blood flow/

, Δ blood flow/ , or

, or  in CHF rats.

in CHF rats.

Figure 2. Average raw  profiles for healthy (left panel, n = 14) and CHF (right panel, n = 12) rats during control and SMTC conditions.

profiles for healthy (left panel, n = 14) and CHF (right panel, n = 12) rats during control and SMTC conditions.

Uni-directional SEM bars are shown for clarity. Time ‘0’ represents the onset of contractions.

Table 3.

Microvascular partial pressure of O2 ( ) at baseline and

) at baseline and  kinetics parameters during contractions before (control) and after SMTC in healthy and CHF rats

kinetics parameters during contractions before (control) and after SMTC in healthy and CHF rats

| Healthy | CHF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | SMTC | Control | SMTC | |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

29.7 ± 1.4 | 34.4 ± 1.9* | 25.7 ± 1.6 | 28.6 ± 2.1† |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

11.9 ± 0.9 | 14.2 ± 1.2 | 11.3 ± 1.1 | 12.1 ± 1.0 |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

3.4 ± 0.8 | 2.1 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 1.0 |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

9.9 ± 0.9 | 13.7 ± 1.1* | 8.7 ± 1.1 | 10.9 ± 1.1 |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

19.8 ± 1.7 | 20.7 ± 1.8 | 17.0 ± 1.4 | 17.7 ± 1.8 |

| TD1 (s) | 8.7 ± 0.8 | 5.5 ± 0.5* | 9.6 ± 0.7 | 6.8 ± 1.2* |

| TD2 (s) | 40.2 ± 6.8 | 38.8 ± 5.4 | 63.2 ± 13.2 | 99.5 ± 22.6† |

| τ1 (s) | 15.5 ± 1.5 | 12.9 ± 1.2 | 13.2 ± 2.6 | 14.5 ± 2.6 |

| τ2 (s) | 35.4 ± 3.2 | 25.9 ± 11.7 | 50.6 ± 12.6 | 22.4 ± 15.2 |

| MRT (s) | 24.2 ± 2.0 | 18.5 ± 1.3* | 22.8 ± 2.6 | 21.3 ± 3.0 |

(mmHg s−1) (mmHg s−1) |

0.9 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2* | 1.2 ± 0.2 | 1.1 ± 0.2 |

Values are mean ± SEM. Where two-component models were indicated the values shown reflect data from only those animals (healthy control: n = 11, healthy SMTC: n = 4, CHF control: n = 10, CHF SMTC: n = 4).  , pre-contracting

, pre-contracting  ;

;  , amplitude of the first component;

, amplitude of the first component;  , amplitude of the second component;

, amplitude of the second component;  ; overall amplitude regardless of one- or two-component model fit;

; overall amplitude regardless of one- or two-component model fit;  , contracting steady-state

, contracting steady-state  ; TD1, time delay for the first component; TD2, time delay for the second component; τ1, time constant for the first component; τ2, time constant for the second component; MRT, TD1+τ1;

; TD1, time delay for the first component; TD2, time delay for the second component; τ1, time constant for the first component; τ2, time constant for the second component; MRT, TD1+τ1;  , the relative rate of

, the relative rate of  fall. *P < 0.05 versus control, †P < 0.05 versus healthy.

fall. *P < 0.05 versus control, †P < 0.05 versus healthy.

Figure 3. Effects of nNOS inhibition with SMTC on resting and contracting steady-state spinotrapezius muscle  in healthy (n = 14) and CHF (n = 12) rats.

in healthy (n = 14) and CHF (n = 12) rats.

Data are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control.

Figure 4. Effects of nNOS inhibition with SMTC on resting and contracting steady-state spinotrapezius muscle blood flow in healthy (n = 14) and CHF (n = 12) rats.

Data are means ± SEM. *P < 0.05 versus control, †P < 0.05 versus healthy.

Figure 5. Effects of nNOS inhibition with SMTC on contracting steady-state spinotrapezius muscle blood flow (Δ blood flow),  (

( ) and the blood flow/

) and the blood flow/ relationship (Δ blood flow/

relationship (Δ blood flow/ , which dictates the steady-state

, which dictates the steady-state  ).

).

Note how nNOS inhibition did not alter contracting Δ blood flow/ in healthy (n = 14) or CHF (n = 12) rats; but these values were achieved very differently (i.e. blood flow and

in healthy (n = 14) or CHF (n = 12) rats; but these values were achieved very differently (i.e. blood flow and  reductions in healthy rats compared to no changes in CHF rats). Data are means ± SEM. #P < 0.05 versus zero.

reductions in healthy rats compared to no changes in CHF rats). Data are means ± SEM. #P < 0.05 versus zero.

In healthy rats, SMTC did not change spinotrapezius muscle VC at rest (control: 0.13 ± 0.03, SMTC: 0.09 ± 0.01 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1, P > 0.05) whereas it was reduced significantly following SMTC during contractions (control: 0.84 ± 0.13, SMTC: 0.59 ± 0.07 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1, P < 0.05). In contrast in CHF rats, SMTC did not alter VC at rest (control: 0.06 ± 0.01, SMTC: 0.06 ± 0.01 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1, P > 0.05) or during contractions (control: 0.48 ± 0.06, SMTC: 0.44 ± 0.05 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1, P > 0.05).

Kidney blood flow was reduced significantly following SMTC in both healthy (control: 498 ± 38, SMTC: 315 ± 30 ml min−1 (100 g)−1, P < 0.05) and CHF (control: 437 ± 23, SMTC: 343 ± 23 ml min−1 (100 g)−1, P < 0.05) rats. Similarly, SMTC reduced significantly kidney VC in healthy (control: 4.57 ± 0.40, SMTC: 2.45 ± 0.24 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1, P < 0.05) and CHF (control: 3.54 ± 0.19, SMTC: 2.57 ± 0.17 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1, P < 0.05) rats. However, the ΔVC following SMTC was significantly greater in healthy (–2.12 ± 0.43 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1) compared to CHF rats (−0.97 ± 0.29 ml min−1 (100 g)−1 mmHg−1, P < 0.05 versus healthy).

Effects of CHF on nNOS-mediated regulation of muscle contractile function

SMTC had no effect on muscle force production at any individual time point in healthy or CHF animals (P > 0.05 for all). However, in healthy rats, SMTC elevated significantly the muscle force-time integral by 11 ± 4% (P < 0.05 versus zero) whereas there was no effect of SMTC in CHF rats (1 ± 4%, P > 0.05 versus zero).

Discussion

The principal novel finding of the present investigation is that nNOS-mediated control of skeletal muscle microvascular function and  are impaired, and may even be abolished, in CHF rats. Specifically, the nNOS inhibition-induced changes in

are impaired, and may even be abolished, in CHF rats. Specifically, the nNOS inhibition-induced changes in  , blood flow and

, blood flow and  evident in healthy rats were essentially absent in CHF rats. These results suggest that improvements in nNOS function specifically may help restore, at least in part, the exercise and functional decrements evidenced by CHF patients.

evident in healthy rats were essentially absent in CHF rats. These results suggest that improvements in nNOS function specifically may help restore, at least in part, the exercise and functional decrements evidenced by CHF patients.

Effects of CHF on nNOS-mediated regulation of

In healthy rats, nNOS inhibition elevated resting baseline  consequent to reductions in resting

consequent to reductions in resting  . In this sense, the absence of

. In this sense, the absence of  elevation in CHF rats following SMTC represents the loss of nNOS-mediated control of resting mitochondrial respiration. In healthy rats, nNOS-derived NO slowed the

elevation in CHF rats following SMTC represents the loss of nNOS-mediated control of resting mitochondrial respiration. In healthy rats, nNOS-derived NO slowed the  kinetics fall following contractions onset as evidenced by the nNOS inhibition-induced reduction of the TD1 and MRT and the greater

kinetics fall following contractions onset as evidenced by the nNOS inhibition-induced reduction of the TD1 and MRT and the greater  . In CHF rats, only the shorter TD1 following nNOS inhibition was evident, which denotes that at least a relatively small nNOS-derived NO contribution to the initial

. In CHF rats, only the shorter TD1 following nNOS inhibition was evident, which denotes that at least a relatively small nNOS-derived NO contribution to the initial  and/or blood flow adjustment is preserved during contractions. Interestingly though, this nNOS contribution to

and/or blood flow adjustment is preserved during contractions. Interestingly though, this nNOS contribution to  regulation immediately following contractions onset appears to diminish as contractions persist. Specifically, the contracting steady-state

regulation immediately following contractions onset appears to diminish as contractions persist. Specifically, the contracting steady-state  was not different between control and SMTC conditions in healthy and CHF rats. However, in healthy rats this resulted from similar 15% reductions in blood flow and

was not different between control and SMTC conditions in healthy and CHF rats. However, in healthy rats this resulted from similar 15% reductions in blood flow and  whereas in CHF there was no effect of SMTC on steady-state blood flow or

whereas in CHF there was no effect of SMTC on steady-state blood flow or  . While this may reflect the highly regulated nature of skeletal muscle

. While this may reflect the highly regulated nature of skeletal muscle  during contractions, such regulation is achieved very differently (i.e. similar reductions in blood flow and

during contractions, such regulation is achieved very differently (i.e. similar reductions in blood flow and  for healthy rats versus unchanged values for CHF).

for healthy rats versus unchanged values for CHF).

Effects of CHF on nNOS-mediated regulation of O2 delivery,  and contractile function

and contractile function

The potential for nNOS-derived NO specifically to modulate skeletal muscle blood flow in healthy subjects is well-recognized (Thomas et al. 1998; Seddon et al. 2008; Copp et al. 2010b, 2011). While nNOS-derived NO may not be obligatory for the hyperaemic response to treadmill exercise in healthy rats due to multiple redundant blood flow pathways (Copp et al. 2010b), our recent investigation revealed novel roles for nNOS-mediated regulation of O2 delivery/utilization in healthy rat spinotrapezius muscle during electrically induced contractions (Copp et al. 2011). The present investigation is the first to find that CHF impairs this modulation as indicated by nNOS inhibition-induced reductions in contracting blood flow and VC in healthy but not CHF rats. Our present finding is consistent with the observation that contracting skeletal muscle functional sympatholysis (an nNOS-driven phenomenon, Thomas et al. 1998) is attenuated in CHF rats (Thomas et al. 2001). It is noteworthy that compromised nNOS function is likely to account for only a portion of the blood flow decrements observed in CHF and, therefore, dysfunction of other mechanisms of vascular control (i.e. eNOS function, autoregulation, muscle-pump, etc.) must also contribute to the impairment. Interestingly, SMTC reduced kidney blood flow and VC in healthy and CHF rats although the VC reduction in CHF was less than that in healthy rats. Therefore, the degree to which CHF alters nNOS-mediated vascular control evidences heterogeneity among varying tissues and, therefore, possibly among muscles of different fibre-type composition given reports of muscle-fibre type specific CHF-related alterations (Delp et al. 1997; Behnke et al. 2004; Bertaglia et al. 2011). Whether the nNOS-mediated vascular control impairments evident currently are manifest in CHF rats during locomotory exercise remains to be determined.

The SMTC-induced  reductions in healthy rat skeletal muscle at rest and during contractions was surprising given the potential for NO to inhibit mitochondrial respiration via competitive inhibition at cyctochrome c oxidase (Brown, 1995), but are consistent with previous studies reporting reductions in rat hindlimb

reductions in healthy rat skeletal muscle at rest and during contractions was surprising given the potential for NO to inhibit mitochondrial respiration via competitive inhibition at cyctochrome c oxidase (Brown, 1995), but are consistent with previous studies reporting reductions in rat hindlimb  following non-selective NOS inhibition (Krause et al. 2005; Baker et al. 2006). The findings in healthy rats indicate that nNOS-derived NO may actually stimulate oxidative phosphorylation. The present study demonstrates that CHF impairs, and may abolish, the nNOS-mediated effects on

following non-selective NOS inhibition (Krause et al. 2005; Baker et al. 2006). The findings in healthy rats indicate that nNOS-derived NO may actually stimulate oxidative phosphorylation. The present study demonstrates that CHF impairs, and may abolish, the nNOS-mediated effects on  . However, nNOS inhibition improved muscle contractile performance (i.e. modestly elevated force-time integral) in healthy rats, which is consistent with the notion that NO exerts an inhibitory influence on muscle contractile function (Reid et al. 1998). Taken together, the elevated force–time integral and reduced

. However, nNOS inhibition improved muscle contractile performance (i.e. modestly elevated force-time integral) in healthy rats, which is consistent with the notion that NO exerts an inhibitory influence on muscle contractile function (Reid et al. 1998). Taken together, the elevated force–time integral and reduced  during contractions in healthy rats suggests an elevated contractile economy. Therefore, the data indicate that the nNOS-mediated effects on contractile function and economy are curtailed in CHF rats. By extension, the muscle contractile dysfunction evident in CHF subjects (Perreault et al. 1993; Lunde et al. 2002; Ertunc et al. 2009) must occur via dysregulation/dysfunction of other mechanisms occurring simultaneous with nNOS downregulation. For example, CHF induces elevated intracellular iNOS, which correlates with exercise intolerance (Hambrecht et al. 1999), and impaired sarcoplasmic reticulum function and calcium regulation (Perreault et al. 1993; Reiken et al. 2003), which likely contribute to contractile dysfunction in CHF.

during contractions in healthy rats suggests an elevated contractile economy. Therefore, the data indicate that the nNOS-mediated effects on contractile function and economy are curtailed in CHF rats. By extension, the muscle contractile dysfunction evident in CHF subjects (Perreault et al. 1993; Lunde et al. 2002; Ertunc et al. 2009) must occur via dysregulation/dysfunction of other mechanisms occurring simultaneous with nNOS downregulation. For example, CHF induces elevated intracellular iNOS, which correlates with exercise intolerance (Hambrecht et al. 1999), and impaired sarcoplasmic reticulum function and calcium regulation (Perreault et al. 1993; Reiken et al. 2003), which likely contribute to contractile dysfunction in CHF.

Mechanisms of nNOS dysfunction in CHF

Previous investigations have reported increased (Rush et al. 2005) or unchanged (Thomas et al. 2001; Rush et al. 2005) nNOS expression in skeletal muscle from CHF rats suggesting that the impaired nNOS-mediated microvascular function reported presently reflects reduced nNOS-derived NO bioavailability. This may occur consequent to reduced NO production resulting from nNOS uncoupling following the loss of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and other essential NOS cofactors (Munzel et al. 2005) and/or enhanced nNOS-derived NO inactivation by reactive O2 species (i.e. superoxide). Specifically, elevated reactive O2 species may inactivate NO and are the result of CHF-induced increases in muscle oxidoreductases such as, for example, xanthine oxidase (Landmesser et al. 2002) which may occur concurrent with reductions in superoxide dismutase and catalase antioxidant protein levels (Rush et al. 2005). These effects are likely to contribute to the elevated biomarkers of oxidative stress found in CHF patients (Seddon et al. 2007). In addition, elevated levels of the endogenous NOS inhibitor asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) have been reported in the circulation of CHF patients (Usui et al. 1998) and animals (Feng et al. 1998) and it is possible that this substance impairs nNOS function simultaneously with its better-known impediments to eNOS function.

Methodological considerations

Several key lines of evidence support that 0.56 mg kg−1 of SMTC inhibited nNOS without impacting eNOS-mediated function. First, Furfine et al. (1994) demonstrated that SMTC possesses a 10-fold selectivity for nNOS versus eNOS in vitro and a 17-fold selectivity for nNOS versus eNOS in rat tissue in vivo. Second, SMTC did not alter the recovery of the hypotensive response to ACh (mediated largely by eNOS-derived NO) whereas l-NAME significantly blunted the response. However, when the SMTC dose is increased to 5.6 mg kg−1 (i.e. 10-fold) a clear impact is seen on the ACh response (authors’ unpublished data). Analysis of hemodynamic responses to ACh has constituted the gold-standard assessment of selective nNOS inhibition when SMTC is administered either locally or systemically in intact animal and human models (Wakefield et al. 2003; Seddon et al. 2008, 2009; Copp et al. 2010b, 2011). Third, 0.56 mg kg−1 SMTC did not impact rat hindlimb skeletal muscle blood flow during treadmill exercise (Copp et al. 2010b). If SMTC inhibited eNOS significant reductions in blood flow would be expected as seen following l-NAME (Hirai et al. 1995). Fourth, the present SMTC dose is similar to that used in investigations from other laboratories that have also reported selective nNOS inhibition with SMTC in rats in vivo (0.3 mg kg−1, Ichihara et al. 1998; 0.5 mg kg−1, Komers et al. 2000).

Other methodological considerations including time control studies, the validity of the intact spinotrapezius muscle preparation, isolated electrical-contractions paradigm, and systemic versus local SMTC administration have been discussed in detail previously (Copp et al. 2011).

Conclusions

The nNOS-mediated regulation of  , muscle blood flow and

, muscle blood flow and  is dramatically impaired, if not abolished, in CHF rats. Additionally, nNOS-derived NO inhibits force production in healthy rats and this nNOS-mediated inhibition is suppressed in CHF rats. Investigation of the mechanisms underlying impaired microvascular and muscle function in CHF is critical for the development of treatments designed to mitigate CHF-induced skeletal muscle pathology. Given the impairments of nNOS-mediated

is dramatically impaired, if not abolished, in CHF rats. Additionally, nNOS-derived NO inhibits force production in healthy rats and this nNOS-mediated inhibition is suppressed in CHF rats. Investigation of the mechanisms underlying impaired microvascular and muscle function in CHF is critical for the development of treatments designed to mitigate CHF-induced skeletal muscle pathology. Given the impairments of nNOS-mediated  regulation in CHF rats reported currently, restoration of nNOS function may constitute a valuable mechanistic target for therapeutic treatments of CHF.

regulation in CHF rats reported currently, restoration of nNOS function may constitute a valuable mechanistic target for therapeutic treatments of CHF.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank K. Sue Hageman and Dr Tadakatsu Inagaki for excellent technical assistance. S.W.C. is supported by an American Heart Association Midwest Affiliate Pre-doctoral Fellowship and D.M.H. is supported by a Fellowship from the Brazilian Ministry of Education/CAPES-Fulbright. These experiments were funded by Kansas State University SMILE awards to D.C.P. and T.I.M. and American Heart Association Midwest Affiliate (10GRNT4350011) and NIH (HL-108328) awards to D.C.P.

Glossary

- ACh

acetylcholine

- CHF

chronic heart failure

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- HR

heart rate

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LV

left ventricle

- LV dp/dt

left ventricular change in pressure over change in time

- LVEDP

left ventricular end diastolic pressure

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MRT

mean response time

- l-NAME

NG-nitro-l-arginine-methyl-ester

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- O2

oxygen

microvascular partial pressure of oxygen

- RV

right ventricle

- SMTC

S-methyl-l-thiocitrulline

- TD

time delay

- VC

vascular conductance

oxygen consumption

Author contributions

Conception and design of the experiments: S.W.C., D.M.H., T.I.M., D.C.P. Data collection and analysis: S.W.C., D.M.H., S.K.F., C.T.H., T.I.M. Manuscript preparation and revision: S.W.C., D.M.H., S.K.F., C.T.H., T.I.M., D.C.P. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Altman P, Dittmer D. Biological Data Book. 2nd edn. Bethesda, MD: FASEB; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JK, Kindig CA, Behnke BJ, Musch TI, Schmid-Schoenbein GW, Poole DC. Spinotrapezius muscle microcirculatory function: effects of surgical exteriorization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H3131–3137. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H3131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DJ, Krause DJ, Howlett RA, Hepple RT. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition reduces O2 cost of force development and spares high-energy phosphates following contractions in pump-perfused rat hindlimb muscles. Exp Physiol. 2006;91:581–589. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.032698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behnke BJ, Delp MD, McDonough P, Spier SA, Poole DC, Musch TI. Effects of chronic heart failure on microvascular oxygen exchange dynamics in muscles of contrasting fiber type. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertaglia RS, Reissler J, Lopes FS, Cavalcante WL, Carani FR, Padovani CR, Rodrigues SA, Cigogna AC, Carvalho RF, Fernandes AA, Gallacci M, Silva MD. Differential morphofunctional characteristics and gene expression in fast and slow muscle of rats with monocrotaline-induced heart failure. J Mol Histol. 2011;42:205–215. doi: 10.1007/s10735-011-9325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GC. Nitric oxide regulates mitochondrial respiration and cell functions by inhibiting cytochrome oxidase. FEBS letters. 1995;369:136–139. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00763-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp SW, Hirai DM, Ferguson SK, Musch TI, Poole DC. Role of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in modulating microvascular and contractile function in rat skeletal muscle. Microcirculation. 2011;18:501–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2011.00111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp SW, Hirai DM, Ferreira LF, Poole DC, Musch TI. Progressive chronic heart failure slows the recovery of microvascular O2 pressures after contractions in the rat spinotrapezius muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010a;299:H1755–1761. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00590.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copp SW, Hirai DM, Schwagerl PJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Effects of neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibition on resting and exercising hindlimb muscle blood flow in the rat. J Physiol. 2010b;588:1321–1331. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delp MD, Duan C, Mattson JP, Musch TI. Changes in skeletal muscle biochemistry and histology relative to fiber type in rats with heart failure. J Appl Physiol. 1997;83:1291–1299. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1997.83.4.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederich ER, Behnke BJ, McDonough P, Kindig CA, Barstow TJ, Poole DC, Musch TI. Dynamics of microvascular oxygen partial pressure in contracting skeletal muscle of rats with chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:479–486. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00545-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond GB. Reporting ethical matters in The Journal of Physiology: standards and advice. J Physiol. 2009;587:713–719. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.167387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertunc M, Sara Y, Korkusuz P, Onur R. Differential contractile impairment of fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscles in a rat model of doxorubicin-induced congestive heart failure. Pharmacology. 2009;84:240–248. doi: 10.1159/000241723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q, Lu X, Fortin AJ, Pettersson A, Hedner T, Kline RL, Arnold JM. Elevation of an endogenous inhibitor of nitric oxide synthesis in experimental congestive heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:667–675. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira LF, Hageman KS, Hahn SA, Williams J, Padilla DJ, Poole DC, Musch TI. Muscle microvascular oxygenation in chronic heart failure: role of nitric oxide availability. Acta Physiologica. 2006a;188:3–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira LF, Padilla DJ, Williams J, Hageman KS, Musch TI, Poole DC. Effects of altered nitric oxide availability on rat muscle microvascular oxygenation during contractions. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2006b;186:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furfine ES, Harmon MF, Paith JE, Knowles RG, Salter M, Kiff RJ, Duffy C, Hazelwood R, Oplinger JA, Garvey EP. Potent and selective inhibition of human nitric oxide synthases. Selective inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by S-methyl-L-thiocitrulline and S-ethyl-L-thiocitrulline. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26677–26683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrecht R, Adams V, Gielen S, Linke A, Mobius-Winkler S, Yu J, Niebauer J, Jiang H, Fiehn E, Schuler G. Exercise intolerance in patients with chronic heart failure and increased expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in the skeletal muscle. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:174–179. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00531-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai DM, Copp SW, Ferreira LF, Musch TI, Poole DC. Nitric oxide bioavailability modulates the dynamics of microvascular oxygen exchange during recovery from contractions. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2010;200:159–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirai T, Zelis R, Musch TI. Effects of nitric oxide synthase inhibition on the muscle blood flow response to exercise in rats with heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 1995;30:469–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichihara A, Inscho EW, Imig JD, Navar LG. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase modulates rat renal microvascular function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 1998;274:F516–524. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.3.F516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishise S, Pegram BL, Yamamoto J, Kitamura Y, Frohlich ED. Reference sample microsphere method: cardiac output and blood flows in conscious rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1980;239:H443–H449. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.239.4.H443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser L, Spickard RC, Olivier NB. Heart failure depresses endothelium-dependent responses in canine femoral artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1989;256:H962–967. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.256.4.H962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SD, Biasucci L, Sabba C, Strom JA, Jondeau G, Galvao M, Solomon S, Nikolic SD, Forman R, LeJemtel TH. Impaired endothelium-mediated vasodilation in the peripheral vasculature of patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992;19:918–925. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90271-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz SD, Krum H, Khan T, Knecht M. Exercise-induced vasodilation in forearm circulation of normal subjects and patients with congestive heart failure: role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;28:585–590. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komers R, Oyama TT, Chapman JG, Allison KM, Anderson S. Effects of systemic inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in diabetic rats. Hypertension. 2000;35:655–661. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DJ, Hagen JL, Kindig CA, Hepple RT. Nitric oxide synthase inhibition reduces the O2 cost of force development in rat hindlimb muscles pump perfused at matched convective O2 delivery. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:889–900. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2005.031567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landmesser U, Spiekermann S, Dikalov S, Tatge H, Wilke R, Kohler C, Harrison DG, Hornig B, Drexler H. Vascular oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic heart failure: role of xanthine-oxidase and extracellular superoxide dismutase. Circulation. 2002;106:3073–3078. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000041431.57222.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo LW, Vinogradov SA, Koch CJ, Wilson DF. A new, water soluble, phosphor for oxygen measurements in vivo. Adv Ex Med Biol. 1997;428:651–656. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5399-1_91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhurst J, Gifford W, Zelis R. Impaired forearm oxygen consumption during static exercise in patients with congestive heart failure. Circulation. 1976;54:477–480. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.54.3.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde PK, Verburg E, Eriksen M, Sejersted OM. Contractile properties of in situ perfused skeletal muscles from rats with congestive heart failure. J Physiol. 2002;540:571–580. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massie B, Conway M, Yonge R, Frostick S, Ledingham J, Sleight P, Radda G, Rajagopalan B. Skeletal muscle metabolism in patients with congestive heart failure: relation to clinical severity and blood flow. Circulation. 1987;76:1009–1019. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.5.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munzel T, Daiber A, Ullrich V, Mulsch A. Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1551–1557. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168896.64927.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musch TI, Terrell JA. Skeletal muscle blood flow abnormalities in rats with a chronic myocardial infarction: rest and exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1992;262:H411–419. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1992.262.2.H411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicoletti I, Cicoira M, Zanolla L, Franceschini L, Brighetti G, Pilati M, Zardini P. Skeletal muscle abnormalities in chronic heart failure patients: relation to exercise capacity and therapeutic implications. Congest Heart Fail. 2003;9:148–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2002.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreault CL, Gonzalez-Serratos H, Litwin SE, Sun X, Franzini-Armstrong C, Morgan JP. Alterations in contractility and intracellular Ca2+ transients in isolated bundles of skeletal muscle fibers from rats with chronic heart failure. Circ Res. 1993;73:405–412. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole DC, Behnke BJ, McDonough P, McAllister RM, Wilson DF. Measurement of muscle microvascular oxygen pressures: compartmentalization of phosphorescent probe. Microcirculation. 2004;11:317–326. doi: 10.1080/10739680490437487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole DC, Hirai DM, Copp SW, Musch TI. Muscle oxygen transport and utilization in heart failure: implications for exercise (in)tolerance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;302:H1050–1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00943.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid MB, Kobzik L, Bredt DS, Stamler JS. Nitric oxide modulates excitation-contraction coupling in the diaphragm. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1998;119:211–218. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(97)00417-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiken S, Lacampagne A, Zhou H, Kherani A, Lehnart SE, Ward C, Huang F, Gaburjakova M, Gaburjakova J, Rosemblit N, Warren MS, He KL, Yi GH, Wang J, Burkhoff D, Vassort G, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation activates the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) in skeletal muscle: defective regulation in heart failure. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:919–928. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200211012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey WL, Vanderkooi JM, Wilson DF. Imaging of phosphorescence: a novel method for measuring oxygen distribution in perfused tissue. Science. 1988;241:1649–1651. doi: 10.1126/science.241.4873.1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush JW, Green HJ, Maclean DA, Code LM. Oxidative stress and nitric oxide synthase in skeletal muscles of rats with post-infarction, compensated chronic heart failure. Acta Physiol Scand. 2005;185:211–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-201X.2005.01479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon M, Looi YH, Shah AM. Oxidative stress and redox signalling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Heart. 2007;93:903–907. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.068270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon M, Melikian N, Dworakowski R, Shabeeh H, Jiang B, Byrne J, Casadei B, Chowienczyk P, Shah AM. Effects of neuronal nitric oxide synthase on human coronary artery diameter and blood flow in vivo. Circulation. 2009;119:2656–2662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.822205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddon MD, Chowienczyk PJ, Brett SE, Casadei B, Shah AM. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase regulates basal microvascular tone in humans in vivo. Circulation. 2008;117:1991–1996. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.744540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons JD, Stebbins CL, Musch TI. Interactions between angiotensin II and nitric oxide during exercise in normal and heart failure rats. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:574–581. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GD, Sander M, Lau KS, Huang PL, Stull JT, Victor RG. Impaired metabolic modulation of α-adrenergic vasoconstriction in dystrophin-deficient skeletal muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15090–15095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GD, Zhang W, Victor RG. Impaired modulation of sympathetic vasoconstriction in contracting skeletal muscle of rats with chronic myocardial infarctions: role of oxidative stress. Circ Res. 2001;88:816–823. doi: 10.1161/hh0801.089341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui M, Matsuoka H, Miyazaki H, Ueda S, Okuda S, Imaizumi T. Increased endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor in patients with congestive heart failure. Life Sci. 1998;62:2425–2430. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield ID, March JE, Kemp PA, Valentin JP, Bennett T, Gardiner SM. Comparative regional haemodynamic effects of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitors, S-methyl-L-thiocitrulline and L-NAME, in conscious rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;139:1235–1243. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]