Abstract

We examined correlates of intimate partner violence (IPV) in a military Veteran sample (N = 129) using Finkel’s (2007) framework for understanding the interactions between impelling and disinhibiting risk factors. Correlates investigated included head contact events (HCEs), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, and antisocial features. Results indicated that antisocial features were significantly associated with IPV at the bivariate level. PTSD symptoms also were associated with IPV, but this association was marginally significant. Tests of moderation provided support for the expectation that HCEs would potentiate associations between antisocial features and IPV. HCEs also moderated the association between PTSD symptoms and IPV. However, contrary to expectations, the opposite pattern emerged such that PTSD symptoms were associated with a higher rate of IPV for those without a history of HCEs. Study findings have potentially important implications for furthering our understanding of the complex etiology of IPV in this population.

Keywords: trauma, veterans, violence, aggression, head injury

Recent models of intimate partner violence (IPV) perpetration emphasize that it is important not only to examine factors that may directly contribute to IPV (impelling factors), but also factors that disinhibit IPV among individuals at increased risk (Finkel, 2007). As Finkel argues, a dyad may experience violent impulses towards each other during an escalating relationship conflict, though they may or may not engage in actual violence due to the presence of inhibitory or disinhibitory factors. According to the model, an individual will only engage in IPV when the strength of impelling forces exceeds the strength of the forces for the inhibition of IPV, and thus it is critical to understand the relevant impelling and inhibiting/disinhibiting forces at play in a particular population and how they interact with each other. The current investigation uses this model as an organizing conceptual framework for examining IPV risk factors in a sample of military Veterans. More specifically, we examine two of the most heavily studied IPV “impelling” risk factors, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and antisocial features, and one potentially disinhibiting risk factor, head contact events (HCEs; i.e., experiencing a concussion or losing consciousness). Prior work with Veterans has focused almost exclusively on identifying simple bivariate correlates of IPV or explanatory (mediator) variables for the PTSD-IPV association. Thus, we attempt to expand the available research base to further the understanding of interactive associations between Finkel’s two risk factor categories of interest.

The Finkel (2007) model is consistent with other theoretical models that attempt to explain aggressive behavior among military Veterans. In particular, information processing models of aggression (Chemtob, Novaco, Hamada, Gross, & Smith, 1997; Taft, Walling, Howard, & Monson, 2010) highlight the role of impelling IPV risk factors, such as PTSD symptoms, and the conditions under which aggression may be more likely to be expressed. Chemtob et al. (1997) argue that when service members are in the war zone, they develop a heightened sense of threat perception. Veterans who develop PTSD often experience disordered perceptions of threat after military service and misinterpret social situations in an overly hostile or negative manner, which increases risk for aggressive behavior. Finkel’s model also highlights the role of disinhibiting factors that may make the expression of that aggression more likely. Taft et al. (2010) similarly argue that disinhibitory factors such as HCEs may further compromise social information processing abilities among individuals experiencing PTSD symptoms and related hostile attributions. HCEs may be a particularly important disinhibiting factor to examine in the context of PTSD since HCEs can co-occur with PTSD at high rates (Hoge et al., 2008; Nelson et al., 2009). They have also been associated with IPV perpetration in civilian and Veteran samples (Cohen, Rosenbaum, Kane, Warnken, & Benjamin, 1999), presumably due, at least in part, to its association with executive functioning deficits that have been linked with IPV (see Pinto et al., 2010).

In the civilian literature, antisocial personality disorder features represent the most heavily studied and most consistently reported correlate of IPV and other forms of aggression (Hamberger & Langhinrichsen-Rohling, 2007; Neumann & Hare, 2008). Surprisingly, there has been little published work examining links between antisocial features and IPV in Veteran populations, and thus we attempted to extend the current literature. Some work focusing more broadly on personality in traumatized populations suggests that the experience of trauma may accentuate underlying “externalizing” personality traits that include antisocial characteristics and related behaviors such as substance use and aggression (see Miller, 2003; Miller & Harrington, in press, for reviews). Specifically, Miller and colleagues hypothesized that trauma exposure may compromise self-regulatory personality processes resulting in the accentuation of latent vulnerabilities towards externalizing behavior. Thus, placed within the context of the Finkel (2007) model and the current study, antisocial features may represent an underlying personality predisposition to behave aggressively, and the presence of a traumatic HCE may serve to accentuate the expression of antisocial behaviors such as IPV.

We tested the following hypotheses: (a) HCEs, PTSD symptoms, and antisocial features would each show significant positive bivariate associations with IPV; (b) HCEs would potentiate associations between PTSD symptoms and IPV; and (c) HCEs would potentiate associations between antisocial features and IPV.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a pool of male Veterans who were screened at the National Center for PTSD/VA Boston Healthcare System (NCPTSD-Boston) between January 2003 and January 2008 for possible evaluation and/or treatment in the clinic. The present study includes 129 male Veterans who completed a set of psychometric instruments for the full evaluation, including medical history, and who indicated that they had been exposed to combat by endorsing any item on the Combat Exposure Scale (Keane et al., 1989). The current sample comprised a subgroup of the sample examined in Taft et al. (2009); specifically, those who reported being in an intimate relationship during the year before the assessment and those who completed all study measures.

The sample averaged 53 years in age (SD = 11.8). Seventy-six percent of the sample self-identified as Caucasian; 11%, 1.6%, and 1.6% self-identified as African American, Hispanic or American Indian, and Other, respectively. Most participants served during the Vietnam War (65%); a minority served during Operation Desert Storm (13%), Operation Iraqi Freedom (10%), Operation Enduring Freedom (3%), Korean War (2%), World War II (2%), and other eras (6%). Fifty-six percent were Veterans of the Army, 25% Marines, 7% Navy, 6% Air Force, and 5% National Guard. Please see Taft et al. (2009) for a more detailed description of the sample.

Procedures

This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the VA Boston Healthcare System. Data were collected from a multi-session, diagnostic evaluation aimed at assessing the presence of current combat-related PTSD. Evaluations were conducted by doctoral-level clinical psychologists or supervised pre-doctoral clinical psychology trainees. A diagnosis of PTSD was determined by the clinician based on the results of the full evaluation, which included a psychosocial and medical history, mental status examination, the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (a structured diagnostic interview for PTSD) (Blake et al., 1990), as well as the battery of psychometric measures. Of the study participants, 85% received a diagnosis of PTSD.

Measures

HCEs

In the medical history portion of the assessment, participants were asked to indicate, in a Yes/No format, whether they had ever experienced a head injury in childhood (prior to age 18), whether they had ever lost consciousness in childhood (prior to age 18), and whether they had ever had a concussion in adulthood (post age 18). A total HCE score was computed by summing the number of times participants indicated ‘yes’ in response to these items.

Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD

(Keane, Caddell, & Taylor, 1988). This 35-item self-report instrument assesses the re-experiencing, avoidance and numbing, and hyperarousal criteria for PTSD, as well as features commonly associated with PTSD, such as substance abuse, depression, sleep disturbance, and suicidality. Participants were asked to rate how they felt about each item using a response scale ranging from 1 (never true) to 5 (very frequently/almost always true). Items were then summed to provide a continuous measure of PTSD symptom severity. One item was removed for this study (“If someone pushes me too far, I am likely to become violent”) because it overlapped with the aggression outcome. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this study was 0.91.

Minnesota Multiphasic Inventory II, Antisocial Practices Scale

(MMPI-II, APS; Butcher, Graham, Williams, & Ben-Porath, 1990). The APS scale is a content scale of the MMPI-II that is designed to assess antisocial behaviors associated with psychopathy. The measure has been shown to be highly correlated with indices of antisocial behavior (e.g., legal problems, aggression) in addition to indices of psychopathic personality traits (e.g., manipulativeness, fearlessness, externalization of blame, dishonesty; Lilienfeld, 1996). Participants were asked to respond to the full 567-item MMPI-II, which included the 22 true/false items of the ASP scale. Item endorsements were summed to yield a total APS score. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this study was .63.

Revised Conflict Tactics Scales

(CTS; Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996). IPV was measured using the 12-item Physical Assault subscale of the CTS2. Participants were asked to rate the frequency with which they had engaged in behaviors toward their partner in the past year on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). Items were recoded to reflect the estimated frequency of the behavior (e. g., 3 to 5 times received a score of 4) and then summed. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the CTS2 Physical Assault subscale was 0.77.

Statistical Analyses

The Mplus software program (version 5.1; Muthen & Muthen, 1998-2008) was used for all analyses. The IPV measure was a count of aggressive behaviors over a specific period of time (i.e., frequency), which was substantially positively skewed. Therefore, we used Poisson regression, which is the most appropriate analytic procedure when analyzing count or frequency outcomes (Gagnon, Doron-Lamarca, Bell, O’Farrell, & Taft, 2008).

After descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among all study variables were computed, Poisson regression analyses were conducted to test the primary hypotheses. Two sets of regressions were conducted; the first included PTSD symptoms, HCEs, and their interaction in predicting IPV; the second examining antisocial features, HCEs, and their interaction in predicting IPV. All continuous predictors were mean centered and all interaction terms were created using the mean centered variables (Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). In the first step, each predictor variable was entered to assess their independent contribution in predicting physical partner aggression. In the second step, the two-way interaction terms were entered.

Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for all study variables. Approximately 33% of participants endorsed at least one act of IPV in the previous year. Forty percent of participants endorsed at least one item on the HCE measure. In contrast to our hypotheses, only one of the predictors, antisocial features, exhibited a significant bivariate association with IPV. PTSD symptom severity also was associated with IPV, although this association was marginally significant (p = .05). The experience of HCE was not associated with any of the other predictor variables, nor was it associated with IPV. Finally, antisocial features were significantly and positively associated with PTSD symptom severity.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations among study variables.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HCEs | .60 | .89 | |||

| 2. PTSD Symptoms | −.13 | 111.08 | 21.18 | ||

| 3. Antisocial Features | .02 | .17* | 55.52 | 10.25 | |

| 4. IPV | −.09 | .18t | .20* | 2.46 | 5.52 |

Note. HCEs = Head Contact Events

PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

IPV = Intimate Partner Violence

p < .05; t p = .05

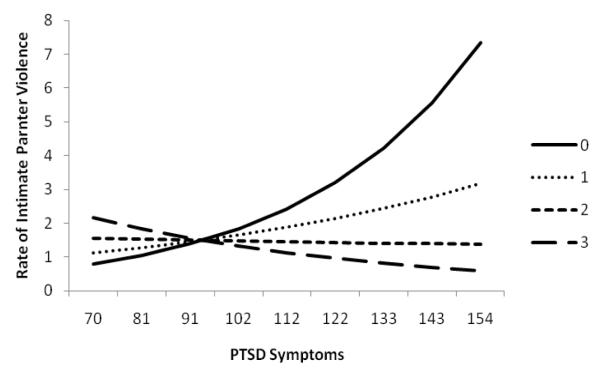

Results from the Poisson regression analyses examining the main and interaction effects of HCEs, PTSD symptom severity, and antisocial features on IPV are summarized in Table 2. For HCEs and PTSD symptoms, results showed that at Step 1, PTSD symptoms were uniquely associated with IPV after controlling for HCEs. Specifically, higher PTSD symptoms were associated with a higher rate of IPV; HCE scores were not independently associated with IPV. However, the main effect of PTSD symptoms was qualified by a significant two-way interaction between HCEs and PTSD symptom severity at Step 2 (p < .05). Simple slopes tests showed that for those with no reported HCEs, higher PTSD symptoms were associated with a higher rate of IPV perpetration (incidence density ratio (IDR) = 1.03, p < .05). For those who experienced HCEs however, there was no significant association between PTSD symptoms and IPV perpetration (see Figure 1).

Table 2.

Summary of Poisson regression analyses predicting intimate partner violence

| Variable | IDR | [95% CI] | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| HCES & PTSD | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| HCEs | .79 | .50, 1.23 | ns |

| PTSD Symptoms | 1.02 | 1.00, 1.04 | < .05 |

| Step 2 | |||

| HCEs × PTSD Symptoms | .99 | .97, 1.00 | < .05 |

| HCEs & Antisocial Features | |||

| Step 1 | |||

| HCEs | .75 | .49, 1.14 | ns |

| Antisocial Features | 1.04 | 1.01, 1.07 | < .05 |

| Step 2 | |||

| HCEs × Antisocial Features | 1.05 | 1.00, 1.10 | < .05 |

Note. HCEs = Head Contact Events

PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

IDR = incidence density ratio

CI = confidence interval

Figure 1.

The effect of PTSD symptoms on IPV as HCE endorsement increases.

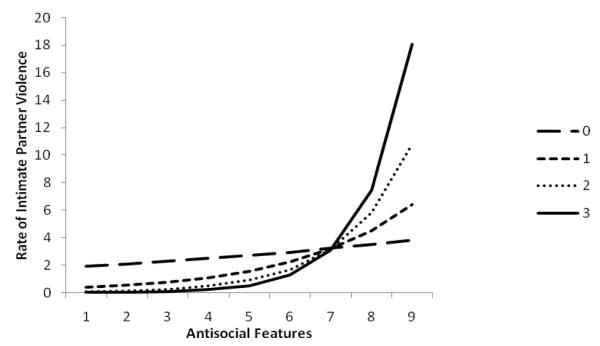

For HCEs and antisocial features, results show that at Step 1, antisocial features were uniquely associated with IPV perpetration after controlling for HCEs. Specifically, higher antisocial features were associated with a higher rate of IPV perpetration; HCE scores were not independently associated with IPV perpetration. Importantly, the main effect of antisocial features was qualified by a significant two-way interaction between HCEs and antisocial features at Step 2 (p < .05). Simple slopes tests showed that for those who endorsed any or all items on the HCE measure, higher antisocial features were associated with a higher rate of IPV perpetration (IDRs ranging from 1.07-1.18, p < .01). For those who never experienced HCEs however, there was no association between antisocial features and IPV perpetration (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of antisocial features on IPV as HCE endorsement increases.

Discussion

Consistent with the Finkel (2007)) model, we examined potential correlates of IPV perpetration in a help-seeking sample of Veterans, and the extent to which these correlates interacted with each other to predict levels of IPV. At the bivariate level, only antisocial features were significantly associated with IPV, though the PTSD symptom-IPV association was marginally significant. The expectation that HCEs would potentiate associations between PTSD symptoms and IPV was not supported. In fact, the opposite pattern emerged; that is, not experiencing a HCE appeared to increase the risk of IPV as PTSD symptoms increased. The hypothesis that HCEs would potentiate associations between antisocial features and IPV was supported; that is, the risk of perpetrating IPV increased as antisocial features increased for those who experienced head contact events.

Study findings may begin to provide some insight into possible inter-relationships among factors commonly thought to be associated with increased risk for IPV and aggressive behavior more generally. The most notable findings obtained were those suggesting that HCEs and antisocial features can interact when it comes to predicting IPV risk. Among those who may possess underlying antisocial features, having a history of head contact events or loss of consciousness may lead to increased levels of aggressive behavior toward partners. These findings have potentially important implications, suggesting that these two risk factors may best be viewed in concert when conceptualizing elevated IPV risk. Consistent with Finkel’s (2007) model, as well as other theories on externalizing behavior among individuals experiencing trauma reactions (e.g., Miller & Harrington, in press), the presence of underlying antisocial features (impelling influence) becomes a particularly strong IPV risk factor in the context of HCEs (disinhibiting influence). It may be that head trauma events serve to compromise the self-regulation abilities of those with antisocial features who are already at risk for IPV.

Although no prior work has investigated associations among antisocial features, HCEs, and IPV in the population of interest, our findings are consistent with one previous study of impulsive aggression among severe TBI inpatients (Greve, Sherwin, Stanford, Mathias, Love, & Ramzinski, 2001). Specifically, these researchers found elevated levels of antisocial features among TBI patients who engaged in impulsive aggression relative to nonviolent control TBI patients. Our results are also consistent with research and theory in the area of psychopathy, brain function, and aggression that suggests that those with psychopathic characteristics may be more vulnerable to engage in aggressive behavior because they are at greater risk for experiencing frustration due in part to dysfunction in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (see Harenski & Kiehl, 2010).

It is interesting that HCEs did not disinhibit IPV among those higher in PTSD symptoms in this sample. The finding of the opposite pattern, HCEs lessening IPV risk as PTSD symptoms increase, appears counter-intuitive and may represent a spurious finding. These results should be interpreted with caution since they were not hypothesized and run contrary to expectations regarding the disinhibiting effects of HCEs. Future work should attempt to replicate the obtained associations to determine if they are upheld across samples.

There are several study limitations that are important to note. The data used were cross-sectional which limits the ability to draw firmer conclusions regarding directionality of associations. Another important study weakness was our reliance on self-report assessments of the study measures of interest, particularly since the primary study measures could all be influenced by social desirability and/or recall biases. Further, more comprehensive and multi-source assessments (e.g., self-report, collateral report, medical report) of each of the study measures are needed. Our HCE measure limited the degree to which we were able to parameterize HCE reports over the lifespan and conduct finer-grained analyses of HCEs’ contributions to the pattern of findings. Alhough significant and potentially important results were obtained, it is possible that more comprehensive assessments would have better captured the variability of these constructs and altered study findings. Finally, considering that the current sample was composed of clinical service-seeking Veterans at a PTSD outpatient clinic, there are limitations in the generalizability of the study findings.

Study results illustrate that the simple examination of bivariate correlates of IPV, or even mediational models of IPV, may not fully characterize the interplay among key risk factors. Such findings have important clinical implications in that it is important for those who work with Veterans to assess multiple risk factors for IPV and to be aware of the possible interaction between more enduring personality features and the disinhibiting effects of HCEs. It is hoped that these findings will assist in stimulating other work in this population that examines inter-relationships among impelling and disinhibiting risk factors for IPV, and that more complex etiological models for IPV are developed that lead to enhanced interventions to prevent and treat this serious public health problem.

Contributor Information

Casey T. Taft, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, and Boston University School of Medicine

Michael K. Suvak, Department of Psychology, Leslie University

Lorig K. Kachadourian, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, and Boston University School of Medicine

Lavinia A. Pinto, Department of Psychology, Kent State University

Mark M. Miller, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, and Boston University School of Medicine

Jeffrey Knight, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, and Boston University School of Medicine.

Brian P. Marx, National Center for PTSD, VA Boston Healthcare System, and Boston University School of Medicine

References

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, et al. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. Behavior Therapist. 1990;13:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Butcher JN, Graham JR, Williams CL, Ben-Porath YS. Development and use of the MMPI-2 Content Scales. University of Minnesota Press; Minneapolis, MN US: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Chemtob CM, Novaco RW, Hamada RS, Gross DM, Smith G. Anger regulation deficits in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1997;10:17–36. doi: 10.1023/a:1024852228908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ US: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen RA, Rosenbaum A, Kane RL, Warnken WJ, Benjamin S. Neuropsychological correlates of domestic violence. Violence and Victims. 1999;14(4):397–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel EJ. Impelling and inhibiting forces in the perpetration of intimate partner violence. Review of General Psychology. 2007;11(2):193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon DR, Doron-LaMarca S, Bell M, O’Farrell TJ, Taft CT. Poisson regression for modeling count and frequency outcomes in trauma research. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:448–454. doi: 10.1002/jts.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greve KW, Sherwin E, Stanford MS, Mathias C, Love J, Ramzinski P. Personality and neurocognitive correlates of impulsive aggression in long-term survivors of severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury. 2001;15:255–262. doi: 10.1080/026990501300005695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger LK, Langhinrichsen-Rohling J. Antisocial disorders and domestic violence: Treatment considerations. In: Felthous AR, Saβ H, editors. International handbook on psychopathic disorders and the law. Vol 1. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; New York, NY US: 2007. pp. 497–517. [Google Scholar]

- Harenski CL, Kiehl KA. Reactive aggression in psychopathy and the role of frustration: Susceptibility, experience, and control. British Journal of Psychology. 2010;101:401–506. doi: 10.1348/000712609X471067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas J, Cox AL, Engel CC, Castro CA. Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(5):453–463. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Caddell JM, Taylor KL. Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Three studies in reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(1):85–90. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Fairbank JA, Caddell JM, Zimering RT, Taylor KL, Mora CA. Clinical evaluation of a measure to assess combat exposure. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;1(1):53–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld SO. The MMPI–2 Antisocial Practices Content Scale: Construct validity and comparison with the Psychopathic Deviate Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8(3):281–293. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW. Personality and the etiology and expression of PTSD: A three-factor model perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2003;10:373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Miller MW, Harrington KM. Personality factors in resilience to traumatic stress. In: Southwick SM, Litz BT, Charney D, Friedman MJ, editors. Resilience and mental health: Challenges across the lifespan. Cambridge University Press; New York: pp. 56–75. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Muthen L, Muthen B. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition Muthen & Muthen; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LA, Yoash-Gantz RE, Pickett TC, Campbell TA. Relationship between processing speed and executive functioning performance among OEF/OIF Veterans: Implications for postdeployment rehabilitation. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2009;24(1):32–40. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181957016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann CS, Hare RD. Psychopathic traits in a large community sample: Links to violence, alcohol use, and intelligence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(5):893–899. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.5.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto LA, Sullivan EL, Rosenbaum A, Wyngarden N, Umhau JC, Miller MW, et al. Biological correlates of intimate partner violence perpetration. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010;15(5):387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17(3):283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Walling SM, Howard JM, Monson CM. Trauma, PTSD and partner violence in military families. In: MacDermid S, Wadsworth, Riggs D, editors. U.S. military families under stress. Springer; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Weatherill RP, Woodward HE, Pinto LA, Watkins LE, Miller MW, et al. Intimate partner and general aggression perpetration among combat Veterans presenting to a posttraumatic stress disorder clinic. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):461–468. doi: 10.1037/a0016657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tellegen A, Ben-Porath YS. The new uniform T scores for the MMPI–2: Rationale, derivation, and appraisal. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4(2):145–155. [Google Scholar]