Abstract

A wide range of evidence implicates the brain as playing a significant role in ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. The mechanism is thought to involve the intermediary of the autonomic nervous system. Here we briefly consider possible mechanisms by which central neural processing may modulate the myocardial electrophysiology and hence the arrhythmia substrate.

Keywords: Cardiac arrhythmias, Brain, Autonomics

Substantial evidence implicates the autonomic nervous system in the initiation of arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death [1–3]. Both the sympathetic and parasympathetic limbs exert a modulatory role on cardiac electrophysiology. In general, in the ventricle enhanced sympathetic activity is predominantly proarrhythmic and enhanced parasympathetic activity is predominantly antiarrhythmic, whereas in the atrium both limbs may be proarrhythmic.

Autonomic control of the heart as a closed loop system

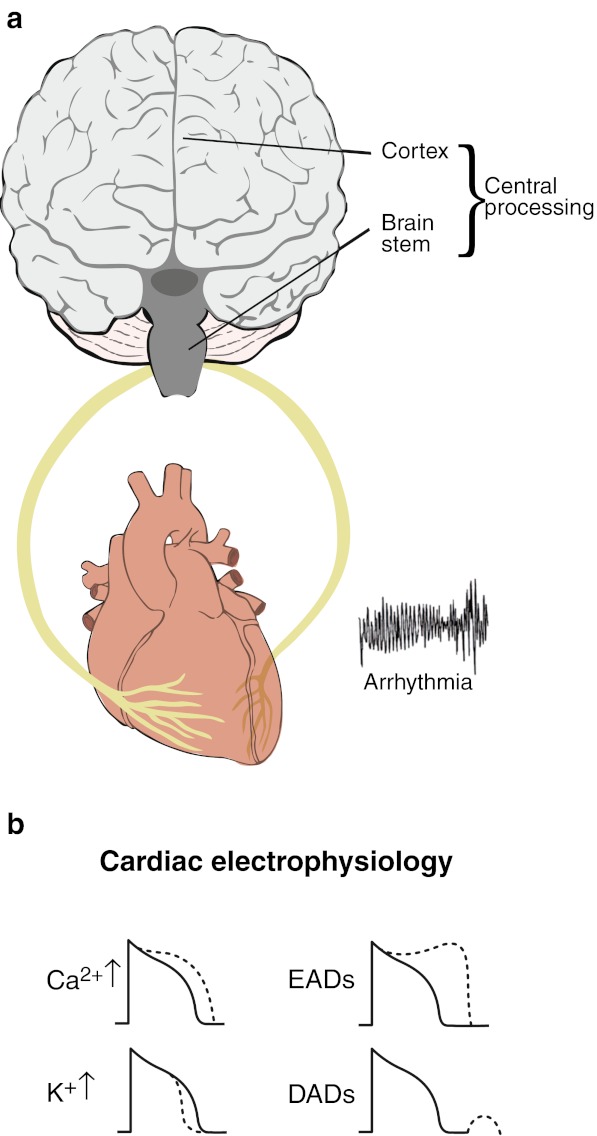

The traditional concept of autonomic control is a closed loop system with the sympathetic and parasympathetic limbs acting in a reciprocal fashion in order to maintain homeostasis (Fig. 1a). Within this system are a number of opponent processing functions. For example, at the level of the myocardial cell membrane, sympathetic stimulation acting through beta 1 adrenergic receptors enhances the inward sarcolemmal calcium current Ica2+ which tends to prolong action potential duration (APD) and refractoriness while at the same time increasing the outward potassium current IKs which tends to shorten APD (Fig. 1b). The net effect under normal circumstances is usually a shortening of APD and refractoriness. These effects are opposed by parasympathetic nerve activity acting pre-junctionally to suppress sympathetic neural stimulation and post-junctionally through muscarinic receptors on the beta-adrenergic signalling cascade. An example of the physiological utility of such a closed-loop system is the baroreflex whereby pressure receptors in the aorta and carotid arteries modulate the balance of efferent sympathetic / parasympathetic outflow to the heart in order to maintain homeostasis. However, a number of factors may interact with and upset the stability of such a system.

Fig. 1.

a The brain and heart as a closed-loop system with right- and left-sided autonomic nerves composed of afferent and efferent sympathetic and afferent and efferent parasympathetic nerves. b Sympathetic stimulation alters the electrophysiology of cardiac myocytes: sarcolemmal calcium current ICa2+ is increased which lengthens action potential duration (APD) and refractoriness; potassium currents, particularly IKs, are increased which shortens APD. The overall effect is usually APD shortening; sympathetic stimulation also favours the formation of early and late afterdepolarisations thereby promoting triggered arrhythmias

Evidence for a role of brain and higher centres in modulating autonomic control and arrhythmogenesis

Evidence for a role of brain and higher centres in ventricular arrhythmias and sudden death includes anecdotal reports throughout the ages of an association with mental stress [4, 5]; an increase in sudden cardiac death at the time of national disasters such as earthquakes [6–9]; magnification of the proarrhythmic effects of ischaemia in animal models by mental stress [10], and the prevention of stress induced VF by fronto-amygdala brain section [11]; a protective effect of vagal stimulation against stress-induced arrhythmias in dogs; a potentiating effect of anger on ventricular arrhythmias [10, 12, 13]; the protective effect of centrally acting beta blockade; and the precipitation of VF in channelopathies such as long-QT syndrome by emotion.

Mechanisms by which brain and higher centres may modulate autonomic control of the heart and influence arrhythmogenesis

Several mechanisms have been proposed whereby higher centres or brain stem regions may participate in arrhythmogenesis [1, 3, 14, 15].

Direct effect via autonomic nerves on myocardial electrophysiology

Autonomic nerve activity may influence the electrophysiology through myocardial ion channels, pumps and transporters and intracellular signalling processes [15]. In the ventricle sympathetic stimulation may exert a number of effects on repolarisation facilitating early and late afterdepolarisations and hence promoting triggered activity, together with shortening of repolarisation and refractoriness and steepening APD restitution thereby promoting reentry (Fig. 1b). Input from higher centres may enhance or reduce sympathetic and parasympathetic drive. A complex interplay exists between the cortical control of autonomic activity and neural traffic in the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. There is considerable evidence supporting specificity whereby different emotions have different autonomic signatures [14, 16].

Lateralised cortical/brain stem activity enhancing inhomogeneity of repolarisation

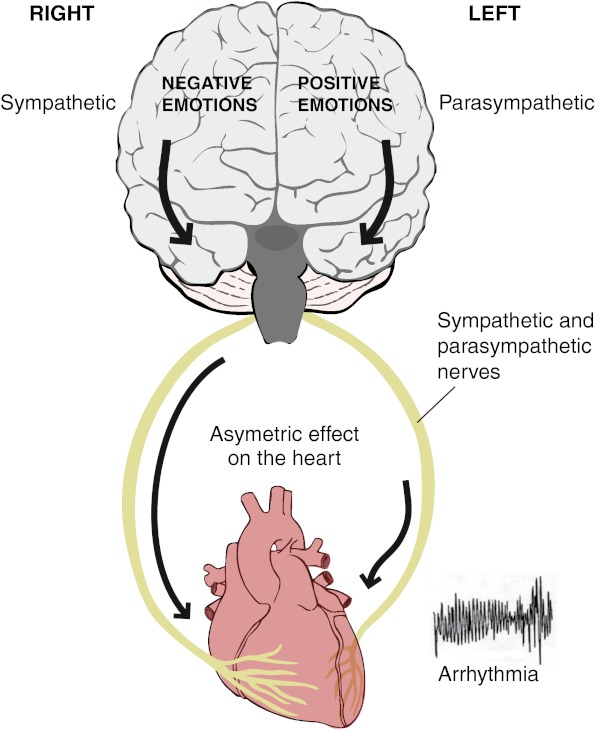

An increase in the normal regional inhomogeneity of repolarisation and refractoriness predisposes to reentrant arrhythmias. Asymmetric autonomic neural traffic to the heart could therefore predispose to reentry. Numerous studies have provided evidence that the two halves of the human forebrain are associated with different emotions. One model ascribes positive emotions to the left hemisphere and negative emotions to the right hemisphere [17]. The control of cardiac activity has been shown to be similarly lateralised with predominantly sympathetic effects arising from the right and parasympathetic effects arising from the left hemisphere [18, 19]. Several studies have suggested a functional lateralisation of autonomic nerves in the heart with the right-sided nerves distributed predominantly over the anterior aspect (right ventricle) and the left-sided nerves distributed predominantly over the posteroinferior aspect (left ventricle) [20]. A functional lateralisation of right and left autonomic nerves on the heart together with lateralised emotional processing in the cortex and ipsilateral conveyance through the brain stem to the autonomic nerves is the basis of the ‘laterality hypothesis’ (Fig. 2) [21, 22].

Fig. 2.

The ‘laterality hypothesis’. In one model of the cortical representation of specific emotions, negative emotions (anger, fear) are processed predominantly in the right hemisphere and positive emotions (e.g. happiness) predominantly in the left hemisphere. The right hemisphere is also predominantly associated with sympathetic activity and the left hemisphere predominantly associated with parasympathetic activity. Conveyance of nerve traffic from brain to heart is mainly ipsilateral. There is a degree of lateralisation of the distribution of the right- and left-sided nerves in the heart with the right-sided nerves mainly on the anterior surface (right ventricle) and the left-sided nerves mainly on the posterior aspect of the heart (left ventricle). The laterality hypothesis proposes a mechanism whereby central neural processing may be represented asymmetrically in the heart and hence generate repolarisation heterogeneity which is known to facilitate reentrant arrhythmias

Afferent/efferent autonomic nerve loops and feedback from higher centres

Cardio-cardiac reflexes are present in the heart which modulate autonomic neural input into the heart in response to afferent information from mechanoreceptors or chemoreceptors in the myocardium thoracic blood vessels and lungs [23]. The baroreflex already mentioned modulates the balance of sympathovagal input to the heart in response to pressure / volume changes in the great vessels. Stimulation of the posteroinferior aspect of the left ventricle may increase parasympathetic input and stimulation of the anterior left ventricle may enhance efferent sympathetic input [23–25]. Recent evidence suggests the possibility of the afferent—efferent feedback loop interacting with higher brain centres above the medullary vasomotor centre [26, 27].

Ischaemia

Sympathetic stimulation is well known to increase oxygen demand and induce epicardial and/or microvascular constriction both of which may create or increase ischaemia. The extent to which ischaemia is an integral part of autonomically mediated arrhythmias is at present unclear.

Arrhythmias may require coexistence of other factors

It is notable that the majority of evidence for an arrhythmogenic role of mental processing derives from subjects with abnormal hearts (e.g. coronary artery disease or channelopathies) or animal models of ischaemia. The very rare occurrence of sudden cardiac death in subjects with normal hearts despite frequent episodes of intense sympathetic stimulation being a common feature of everyday life, suggests that the substrate for arrhythmia requires the coexistence of other factors to create an arrhythmia substrate.

Future directions

Neuroimaging studies in humans are identifying a specific set of cortical and subcortical brain regions involved in cardiac control and arrhythmogenesis (Taggart with Critchley 2011) [14]. Dorsal and subgenual regions of the anterior cingulate cortex, insula cortex and to a lesser extent the amygdala and basal ganglia are key amongst these. In the brainstem the periaqueductal grey and parabrachial nucleus formulate descending drive to the heart by the integration of afferent baroreceptor and mechanoreceptor information. Identifying specific brain regions associated with cardiac risk can thereby suggest novel therapeutic targets for the future.

References

- 1.Zipes DP, Rubart M. Neural modulation of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. Hear Rhythm. 2006;3:108–13. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Verrier RL, Antzelevitch C. Autonomic aspects of arrhythmogenesis: the enduring and the new. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:2–11. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200401000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vaseghi M, Shivkumar K. The role of the autonomic nervous system in sudden cardiac death. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;50:404–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel GL. Sudden and rapid death during psychological stress. Ann Int Med. 1971;74:771–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-5-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams J, Edwards J. The death of John Hunter. JAMA. 1968;204:806–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.1968.03140150023006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trichopoulos D, Katsoutanni K, Zavitsanos X, et al. Psychological stress and fatal heart attack: the Athens earthquake natural experiment. Lancet. 1983;1:441–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(83)91439-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leor J, Poole WK, Kloner RA. Sudden cardiac death triggered by an earthquake. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:413–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602153340701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meisel SR, Kutz I, Dayan KI, et al. Effect of Iraqi missile war on incidence of acute myocardial infarction and sudden death in Israeli civilians. Lancet. 1991;338:660–1. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91234-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinberg JS, Arshad A, Kowalski M, et al. Increased incidence of life threatening arrhythmias in implantable defibrillator patients after the World Trade Centre attack. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1261–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verrier RL. Behavioural stress, myocardial ischemia and arrhythmias. In: Zipes DP, Jalife J, eds. Cardiac electrophysiology: From cell to bedside. Philadelphia:WB Saunders, p. 343–52.

- 11.Skinner JE, Reed JC. Blockade of fronto-cortical brainstem pathway prevents ventricular fibrillation of ischemic heart. Am J Physiol. 1981;249:H156–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1981.240.2.H156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lampert R, Rosenfeld L, Batsford W, et al. Circadian variation of sustained ventricular tachycardia in patients with coronary artery disease and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation. 1994;90:241–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.1.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verrier RL, Hagestad EL, Lown B. Delayed myocardial ischemia induced by anger. Circulation. 1987;75:249–54. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.75.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taggart P, Critchley H, Lambiase PD. Heart-brain interactions in cardiac arrhythmia. Heart. 2011;97:698–708. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2010.209304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taggart P, Boyett MR, Logantha SJRJ, et al. Anger, emotion and arrhythmias: from brain to heart. Front Physiol. 2011;2:67–74. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rainville P, Bechara A, Naqvi N, et al. Basic emotions are associated with distinct patterns of cardiorespiratory activity. Int J Psychphysiol. 2006;61:5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig AD. Forebrain emotional asymmetry: a neuroanatomical basis ? Trends Cogn Sci. 2005;9:566–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oppenheimer SM. Neurogenic effects of cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 1994;7:20–4. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wittling W. Brain asymmetry in the control of autonomic physiologic activity. In: Davidson RJ, Hugdahl KJ, editors. Brain asymmetry. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 1995. pp. 305–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yanowitz F, Preston JB, Abildskov JA. Functional distribution of right and left stellate innervation to the ventricles: production of neurogenic electrocardiographic changes by unilateral alteration of sympathetic tone. Circ Res. 1966;28:416–28. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.18.4.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lane RD, Jennings JR. Hemispheric asymmetry, autonomic asymmetry, and the problem of sudden cardiac death. Brain Laterality 1995;271–304.

- 22.Lane RD, Critchley HD, Taggart P. Asymmetric innervation. In: Waldsrein S, Kop W, Katzel L, eds. Handbook of cardiovascular behavioural medicine. New York: Springer; 2012.

- 23.Hainsworth R. Reflexes from the heart. Am J Physiol. 1991;71:617–58. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1991.71.3.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longhurst JC, Tjen-A-Looi S, Fu L-W. Cardiac sympathetic afferent activation produced by myocardial ischemia and reperfusion: mechanisms and reflexes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;940:74–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Longhust JC. Cardiac and other visceral afferents. In: Robertson D, editor. Primer of the autonomic nervous system. San Diego: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 103–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Critchley HD, Taggart P, Sutton PM, et al. Mental stress and sudden cardiac death: asymmetric midbrain activation as a possible linking mechanism. Brain. 2005;128:75–85. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gray MA, Taggart P, Sutton PM, et al. A cortical potential reflecting cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6818–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609509104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]