Abstract

In this review we discuss the position of electrical neuromodulation as a safe and reversible adjuvant therapy for treatment of patients with chronic cardiac diseases who have become refractory to conventional strategies. In patients with chronic refractory angina, electrical neuromodulation, independent of the applied modality, has shown to reduce complaints of angina, to enhance exercise capacity, to improve quality of life and to employ anti-ischaemic effects. To date, electrical neuromodulation seems to be one of the best adjuvant therapies for these patients. In addition, neuromodulation in the treatment of heart failure and resistant arrhythmias is the subject of several ongoing studies.

Keywords: Electrical neuromodulation, Chronic cardiac diseases

Rationale

Mortality from chronic cardiac disease has significantly decreased in recent years [1]. The reduction is credited to the development and implementation of a myriad of both preventive measures such as lifestyle changes and therapeutic strategies such as medication, implanting of devices and revascularisation procedures. As more and more people survive their heart disease, morbidity of cardiovascular diseases is increasing.

In the current perspective, the growth of morbidity of patients with chronic cardiac diseases, who are refractory to standard strategies, justifies newer therapies to improve their debilitating condition without worsening their prospects. In this short communication, we highlight the role of electrical neuromodulation in the treatment of refractory angina and emerging chronic cardiac diseases.

Refractory angina pectoris

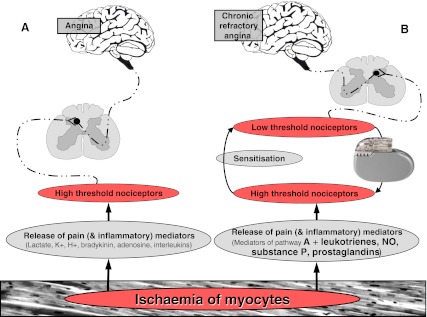

Myocardial ischaemia due to obstructive coronary disease activates both mechanical and chemical cardiac receptors. These receptors trigger the nerves which are conveying signals to the brain, where angina is ultimately ‘felt’. In patients with refractory angina the high-threshold receptors in the myocardium have become low-threshold receptors. The subsequent sensitisation of these receptors in the myocardium results in an altered angina threshold (Fig. 1) [2, 3].

Fig. 1.

Graphic presentation of nervous and neurohumoral pathways in the presence of (chronic) myocardial ischaemia. In patients with chronic angina refractory to conventional therapies, high threshold nociceptors are becoming low threshold nociceptors (=sensitisation), following release of a ‘soup’ of specific mediators. Electrical neuromodulation is thought to ‘normalise’ the lowered thresholds of the nociceptors. a neurohumoral pathway in patients experiencing angina. b neurohumoral pathway in patients with chronic refractory angina

Patients defined as suffering from chronic angina, refractory to conventional anti-ischaemic therapies, have a number of common baseline characteristics (Table 1) [4–7]. Since anti-ischaemic drugs or revascularisation procedures are not adequately reducing complaints of angina, these patients are severely restricted in their exercise capacity, in conjunction with a decreased quality of life (QOL), expressed in, among other things, symptoms of anxiety and depression [8].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with refractory angina pectoris

| Ten Vaarwerk et al. [4] (n = 517) | Zipes et al. [5] (n = 68) | Andréll et al. [6] (n = 235) | Di Pede et al. [7] (n = 104) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) [mean (SD)] | 63.9 (10.1) | 61.1 | 68.6 (10.2) | 69 (10) |

| Male (%) | 71 | 74 | 77 | 67 |

| Cardiovascular status | ||||

| LVEF at rest (%) [mean (SD)] | – | – | – | 48 (13) |

| LVEF ≤ 40 % (%) | 24 | 15 | 16 | – |

| Previous MI (%) | 66 | 74 | 71 | 64 |

| Three vessel disease (%) | 68 | – | – | 88 |

| PTCA (%) | 17 | 71 | 50 | 37 |

| CABG (%) | 58 | 87 | 75 | 46 |

| Drug treatment | ||||

| Calcium channel blockers (%) | 73 | – | 47 | 75 |

| Βeta-blockers (%) | 66 | – | 92 | 60 |

| ACE inhibitors (%) | 25 | – | 59 | 42 |

| Nitrates (%) | 95 | – | 86 | 90 |

| ASA (%) | – | – | – | 91 |

| Diuretics (%) | – | – | – | 37 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Family history of CAD (%) | 61 | – | – | 24 |

| Hypertension (%) | 39 | 81 | 59 | 52 |

| Total cholesterol >5.2 mmol/l (%) | 28 | 93 | – | 52 |

| Smoking (%) | 21 | 78 | – | 33 |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 14 | 49 | 37 | 27 |

References [4, 6, 7] are observational studies and five is a randomised controlled trial (RCT). See reference [17] for all (RCTs)

LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, MI myocardial infarction, PTCA percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, ACE angiotensin converting enzyme, CAD coronary artery disease, ASA acetylsalicylic acid

The exact prevalence and incidence of refractory angina is unknown. However, it has been estimated that at least 200,000 patients are suffering from this condition and another 30,000–50,000 new cases can be diagnosed each year in the USA [8].

Methods of electrical neurostimulation

In 1965, Melzack and Wall proposed the ‘gate control’ theory, which provides a scientific base for electrical neuromodulation [9]. In brief, the authors postulated that stimulation of myelinated thick A-fibres modulate (‘pain’) signals processed in unmyelinated and relatively slow conducting C-fibres, via interneurons in the spinal cord. Braunwald et al. were the first to demonstrate anti-angina and anti-ischaemic effects of stellate ganglion stimulation, implemented through a modified cardiac pacemaker, in 1967 [10].

Since 1982, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), which acts through stimulation of peripheral nerves, is acknowledged as an effective non-invasive treatment for patients with refractory angina. Though effective, TENS is often not an appropriate therapy over time, since the gel pads used to fix the electrodes on the chest frequently cause irritant contact dermatitis and come off easily [11].

Spinal cord stimulation (SCS) was introduced in 1967 [12]. Results of the first study on the anti-angina effects of this technique were published in 1987 [13]. The electrodes are habitually positioned at C7-T2 and connected to a pulse generator (IPG), which is most often implanted at the lateral abdominal side. Activation of the IPG induces paresthesias on the chest, corresponding with the area where angina is experienced.

Subcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (SENS) is a relatively new and promising method, having potential advantages as alternative to TENS and SCS [14]. SENS electrodes are placed subcutaneously, at the side of the sternum in the area where the patient usually feels angina, and are connected to a pulse generator, which is implanted in the abdominal wall. This technique is easier and less invasive compared with SCS, thus reducing the risk of complications.

However, all electrical neuromodulation modalities are reversible, since paresthesias can be withheld at any time and implants can be removed [15].

Anti-angina and anti-ischaemic effect of electrical neuromodulation

The treatment of stable refractory angina with electrical neuromodulation starts with TENS. If TENS is successful, but adverse events occur, treatment with SCS or SENS is instigated. To date, TENS, SCS and SENS have all been proven to be successful within the armamentarium for the treatment of angina.

Many observational and randomised controlled trials have shown an improvement in exercise capacity, a reduction in complaints of angina and a reduced use of short-acting nitrates. Furthermore, an improved QOL, which can persist over a long period of time, has also been demonstrated [16]. Since many of these studies were carried out with a small number of patients, the results are not always consistent. In this respect, two recent meta-analyses on seven randomised controlled trials with SCS, including over 200 patients, show a significant improvement of both exercise capacity and QOL [17, 18].

Regarding anti-ischaemic effects of electrical neuromodulation, TENS is reported to cause a reduction of lactate production in concert with ST-segment depression, during pacing-induced angina [19]. Furthermore, SCS was found to reduce ST-segment depression, in conjunction with an improved exercise capacity [17, 20]. In 2006, De Vries et al. observed that pre-emptive stimulation with TENS, when applied before acute coronary occlusion during PCI, results in an improved collateral perfusion [21]. Other investigators have performed radionuclide and positron emission tomography (PET) studies to investigate the effects of SCS on myocardial perfusion [22].

De Vries and co-workers demonstrate a significant decrease of ST-segment elevation in patients with ST-segment elevated myocardial infarction, following primary PCI during active TENS [20]. Active electrical neuromodulation may subsequently limit the extent of myocardial infarctions. In summary, the anti-ischaemic effects of neurogenic stimulation are thought to be the result of enhancement of ischaemic tolerance of the myocyte, through improvement of both collateral perfusion and myocardial preconditioning [20].

Finally, electrical neuromodulation is considered a safe therapy since angina is experienced during myocardial infarction, even throughout active electrical neuromodulation [20], many studies have demonstrated anti-ischaemic properties and because electrical neuromodulation does not seem to influence morbidity and mortality [4, 6, 7].

Future developments

A neural hierarchy enables the nervous system to optimise and control cardiac functions at the neurocardiac interface, through the so-called intrinsic cardiac nervous system (ICN). Electrical neuromodulation is found to stabilise the ICN, in the presence of ischaemia [23]. In addition, electrical neuromodulation may be further exploited to enable neurons to release the required concentrations of neuro-active chemicals to the jeopardised heart.

Basic studies on heart failure have demonstrated that electrical neuromodulation significantly improves cardiac function and reduces the incidence of spontaneous ventricular arrhythmias [24]. Hence, at least seven clinical studies are ongoing to assess the effect of electrical neuromodulation in patients with heart failure (ClinicalTrials.gov).

Final conclusions

Since many studies demonstrate a reduction in frequency and intensity of angina, increased exercise capacity, reduction in myocardial ischaemia and improvement of quality of life, we conclude that electrical neuromodulation is an effective, reversible and safe adjuvant therapy for patients suffering from refractory angina. Therefore, and because conventional therapies fail to improve the debilitating symptoms of the patients, electrical neuromodulation should be considered as adjunct treatment for these patients.

References

- 1.De Fatima Marinho de Souza M, Gawryszewski VP, Ordunez P, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality in the Americas: current trends and disparities. Heart. 2012;98(16):1207–12. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foreman RD, Qin C. Neuromodulation of cardiac pain and cerebral vasculature: neural mechanisms. Cleve Clin J Med. 2009;76(Suppl 2):S75–9. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.76.s2.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Svorkdal N. Treatment of inoperable coronary disease and refractory angina: spinal stimulators, epidurals, gene therapy, transmyocardial laser, and counterpulsation. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;8(1):43–58. doi: 10.1177/108925320400800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ten Vaarwerk IAM, Jessurun GAJ, DeJongste MJL, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with refractory AP treated with SCS Heart 19998282–9.10377314 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zipes DP, Svorkdal N, Berman D, et al. Spinal cord stimulation therapy for patients with refractory angina who are not candidates for revascularization. Neuromodulation. 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00452.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Andrell P, Yu W, Gersbach P, et al. Long-term effects of spinal cord stimulation on angina symptoms and quality of life in patients with refractory angina pectoris—results from the European angina registry link study (EARL) Heart. 2010;96(14):1132–36. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.177188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Pede F, Lanza GA, Zuin G, et al. Immediate and long-term clinical outcome after spinal cord stimulation for refractory stable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91(8):951–55. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(03)00110-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mannheimer C, Camici P, Chester MR, et al. The problem of chronic refractory angina; report from the ESC joint study group on the treatment of refractory angina. Eur Heart J. 2002;23(5):355–70. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150(3699):971–79. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braunwald E, Epstein SE, Glick G, et al. Relief of angina pectoris by electrical stimulation of the carotid-sinus nerves. N Engl J Med. 1967;277(24):1278–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196712142772402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strobos MA, Coenraads PJ, De Jongste MJ, et al. Dermatitis caused by radio-frequency electromagnetic radiation. Contact Dermatitis. 2001;44(5):309. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0536.2001.440511-2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shealy CN, Taslitz N, Mortimer JT, et al. Electrical inhibition of pain: experimental evaluation. Anesth Analg. 1967;46(3):299–305. doi: 10.1213/00000539-196705000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy DF, Giles KE. Dorsal column stimulation for pain relief from intractable angina pectoris. Pain. 1987;28(3):365–68. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buiten MS, DeJongste MJ, Beese U, et al. Subcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation: a feasible and new method for the treatment of patients with refractory angina. Neuromodulation. 2011;14(3):258–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2011.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mannheimer C, Augustinsson LE, Carlsson CA, et al. Epidural spinal electrical stimulation in severe angina pectoris. Br Heart J. 1988;59(1):56–61. doi: 10.1136/hrt.59.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanza GA, Barone L, Di Monaco A. Effect of spinal cord stimulation in patients with refractory angina: evidence from observational studies. Neuromodulation. 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1403.2012.00430.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Taylor RS, De Vries J, Buchser E, et al. Spinal cord stimulation in the treatment of refractory angina: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borjesson M, Andrell P, Lundberg D, et al. Spinal cord stimulation in severe angina pectoris—a systematic review based on the swedish council on technology assessment in health care report on long-standing pain. Pain. 2008;140(3):501–08. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mannheimer C, Carlsson CA, Ericson K, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in severe angina pectoris. Eur Heart J. 1982;3(4):297–302. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a061311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeJongste MJL. Electrical neuromodulation and the heart with special emphasis on myocardial ischemia. Chapter 7. In: Topics in neuromodulation treatment. ISBN: 978-953-51-0395-0. http://www.intechopen.com/articles/show/title/electrical-neuromodulation-and-the-heart-with-special-focus-on-myocardial-ischemia.

- 21.De Vries J, Anthonio RL, DeJongste MJ, et al. The effect of electrical neurostimulation on collateral perfusion during acute coronary occlusion. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hautvast RW, Blanksma PK, DeJongste MJ, et al. Effect of spinal cord stimulation on myocardial blood flow assessed by positron emission tomography in patients with refractory angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77(7):462–467. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)89338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armour JA, Linderoth B, Arora RC, et al. Long-term modulation of the intrinsic cardiac nervous system by spinal cord neurons in normal and ischaemic hearts. Auton Neurosci. 2002;95(1–2):71–9. doi: 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopshire JC, Zhou X, Dusa C, et al. Spinal cord stimulation improves ventricular function and reduces ventricular arrhythmias in a canine postinfarction heart failure model. Circulation. 2009;120(4):286–94. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.812412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]